Zenker’s diverticulum

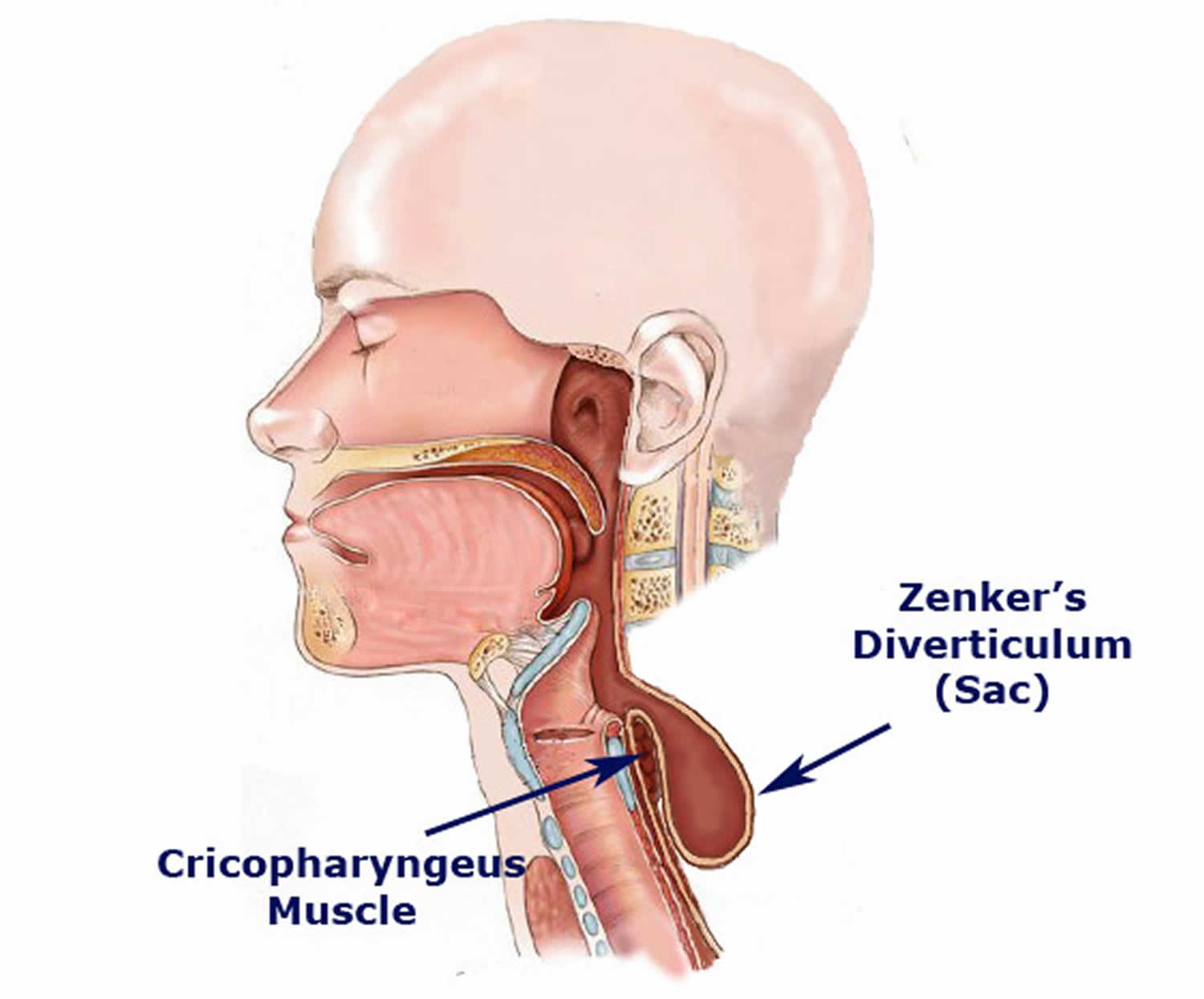

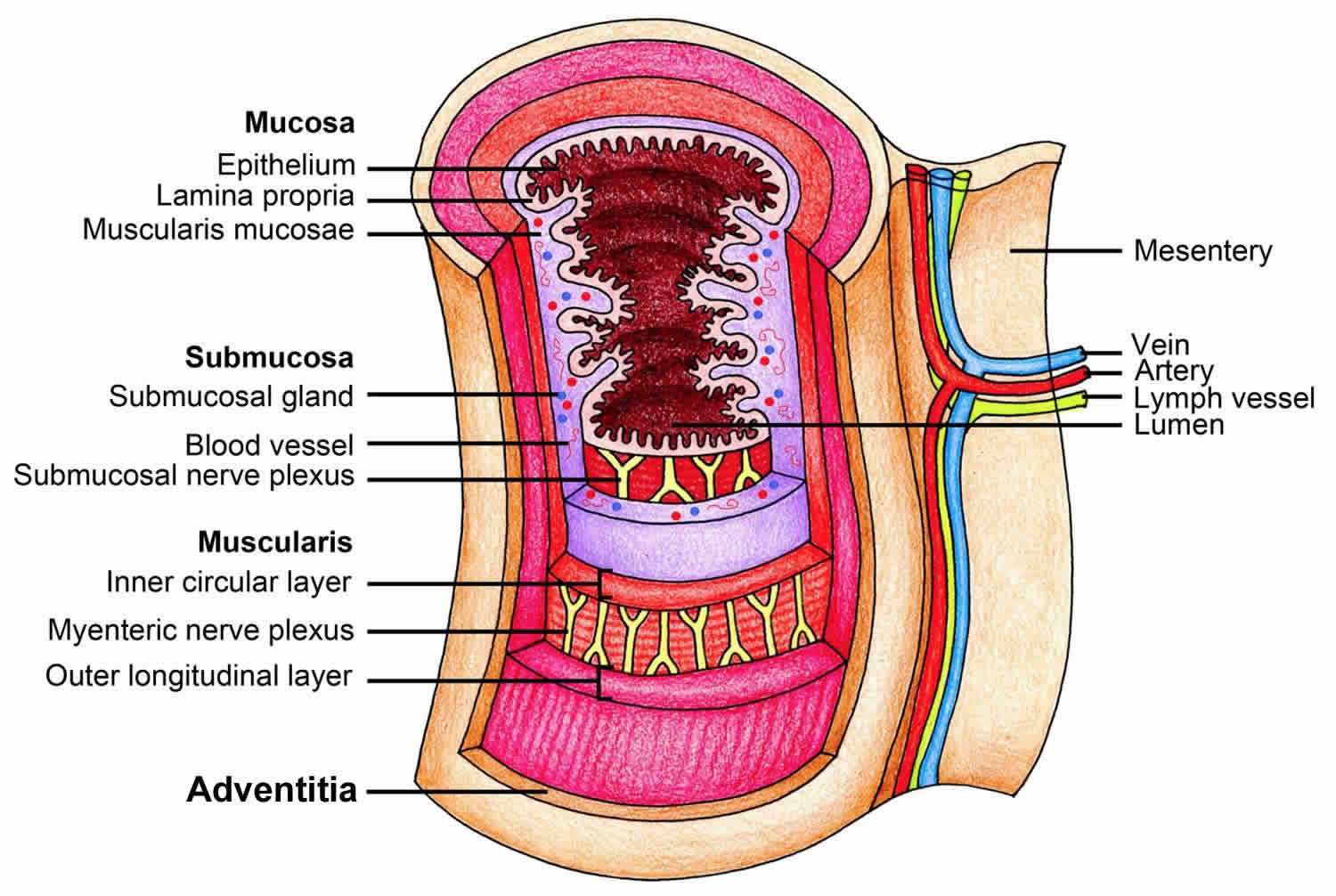

Zenker’s diverticulum also called pharyngeal pouch or pharyngo-esophageal diverticulum, is a posterior outpouching of the hypopharynx involving the esophageal mucosa and submucosa layers into Killian’s triangle, typically in an area of least resistance situated above the cricopharyngeus muscle and below the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle 1. Zenker’s diverticulum is actually a pseudodiverticulum since the Zenker’s pouch contains only esophageal mucosa and submucosa layers and does not involve the muscular layer, hence making it a false diverticulum. Zenker’s diverticulum may also occur in other parts of the esophagus, such as between the oblique and transverse fibers of the cricopharyngeus muscle, known as Killian-Jamieson area, and between the cricopharyngeus muscle and the esophageal muscles, known as Laimer triangle 2.

Zenker’s diverticulum or pharyngeal pouch is a rare esophageal disorder with an annual incidence of just 2 per 100,000 3. Zenker’s diverticulum is more common in men than women and is more commonly seen in people over 60 years of age 4.

Zenker’s diverticulum can cause long-standing difficulty with eating and drinking (dysphagia), weight loss, the pooling of food within the diverticulum, which can cause frequent regurgitation and can lead to aspiration (the passage of food or other hazardous material into the lungs) pneumonia and bad breath.

Zenker’s diverticulum diagnosis may be made by endoscopy, functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing or more reliably, barium swallow with videofluoroscopy. The barium swallow x-ray below (Figure 4) shows a medium sized Zenker’s diverticulum. Note the Zenker’s diverticulum in the region of the esophageal inlet.

Treatment for symptomatic Zenker’s diverticulum can be surgical or endoscopic. The surgical approach involves an external neck incision with cricopharyngeus myotomy (diverticulotomy), with or without pouch intervention (inversion, diverticulopexy or diverticulectomy). The endoscopic approach, using rigid or flexible endoscopes, involves only a diverticulotomy, in which the septum between the esophageal lumen and the diverticulum and the cricopharyngeus muscle are severed to create a single channel.

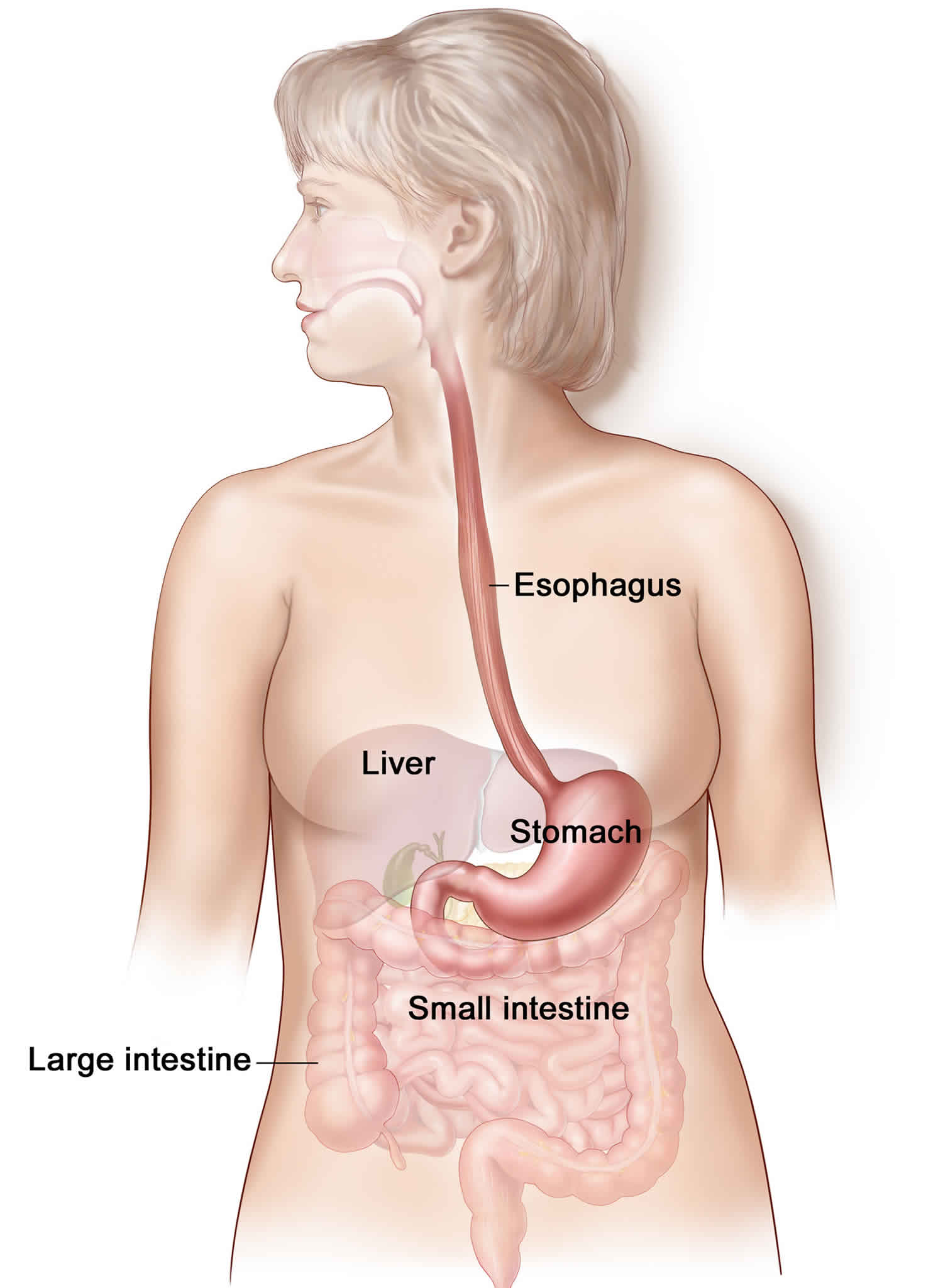

Figure 1. Esophagus

Figure 2. Esophagus anatomy

Figure 3. Zenker’s diverticulum

Figure 4. Zenker’s diverticulum barium swallow esophagogram

Footnote: 70 year old female with a history of regurgitation, dysphagia, and intense halitosis for about 4 years. Barium study of esophagus performed. Diverticulum with a long neck through the posterior wall of the esophagus, compatible with a Zenker diverticulum.

[Source 5 ]Zenker’s diverticulum staging

Zenker’s diverticulum may be staged in 1 of the following 3 systems, as assessed by means of barium swallow videofluoroscopy 6:

Lahey system

Criteria of the Lahey staging system are as follows:

- Stage 1 – A small mucosal protrusion is present

- Stage 2 – A definite sac is present, but the hypopharynx and esophagus are in line

- Stage 3 – The hypopharynx is in line with diverticulum, and the esophagus is indented and pushed anteriorly.

Morton system

Criteria of the Morton staging system are as follows:

- Small sacs are less than 2 cm in length

- Intermediate sacs are 2-4 cm in length

- Large sacs are greater than 4 cm in length

Van Overbeek system

Criteria of the van Overbeek system are as follows:

- Small sacs are less than 1 vertebral body in length

- Intermediate sacs are 1-3 vertebral bodies in length

- Large sacs are greater than 3 vertebral bodies in length

Zenker’s diverticulum causes

A complete understanding of the cause of Zenker’s diverticulum formation is not available. Further studies focused on the function of the cricopharyngeus muscle are likely to be fruitful.

Zenker’s diverticulum forms because the muscle that divides the throat from the esophagus, the cricopharyngeal (cricopharyngeus) muscle, fails to relax during swallowing. The arrangement of muscles in the lower part of the throat, medically known as the hypopharynx, helps support and elevate the pharynx during swallowing. To be efficient in this function, these throat muscles, medically called the constrictors, are arranged at an angle. When you swallow, the brain signals the throat muscles in the hypopharynx to contract. In contracting the muscles of the hypopharynx, the constrictors, elevate the larynx and throat and push the food into the esophagus.

The top of the esophagus is defined by the cricopharyngeus muscle that surrounds the top of the esophagus in a horizontal fashion. The cricopharyngeus muscle is chronically under tension. It functions to keep food in the esophagus between swallows. When you swallow, milliseconds after the throat or pharyngeal muscles contract, the brain sends a signal to the cricopharyngeus muscle to relax and allow the food to go from the throat into the esophagus.

Because the pharyngeal muscles, the constrictors, are at an angle, and the muscle at the top of esophagus, the cricopharyngeus muscle, is horizontal, there is a week area of the pharynx that often does not have muscle. This is a triangular space and is called Killian’s triangle. The size of this space is genetically determined. If the cricopharyngeus muscle at the top of the esophagus does not relax completely or quickly enough, the food that is being swallowed is pushed against the top of the esophagus at the cricopharyngeus muscle and the weak area in Killian’s triangle is pushed out. Eventually a pouch, a Zenker’s diverticulum, can form.

Zenker’s diverticulum symptoms

Patients with a Zenker’s diverticulum experience symptoms when food or secretions get stuck in the pouch. These are usually first noted during the 5th to 7th decade of life. Because the bottom of the pouch is lower than the opening into the throat, secretions and food particles build up in the pouch. Patients feel a need to clear their throat periodically throughout the day or 20 or so minutes after a meal. The solid food particles lodge in the pouch and at times the patient needs to regurgitate these or manually empty them. This causes patients to subconsciously alter their diet to softer foods that are easier to eat and not as difficult to empty from the pouch. If meals are too unpleasant, patients can begin to eat less and then lose weight.

Often the pouch fills and then empties spontaneously into the bottom of the throat causing the patient to cough. Patients with symptoms of Zenker’s diverticulum for a long time have an increase risk and incidence of pneumonia from aspirating these contents. Finally, some patients complain of a belching noise that occurs with swallowing as air trapped in the pouch is squeezed out s the patient is compressed during swallowing.

The combination of the following symptoms is nearly pathognomonic for Zenker’s diverticulum:

- Dysphagia – Most patients (98%) present with some degree of dysphagia

- Regurgitation of undigested food hours after eating

- Sensation of food sticking in the throat

- Special maneuvers to dislodge food

- Coughing after eating

- Aspiration of organic material

- Unexplained weight loss

- Bad breath (halitosis)

- Borborygmi in the neck

Symptoms may last from months to years.

Zenker’s diverticulum complications

The most common life-threatening complication in patients with a Zenker’s diverticulum is aspiration. Other complications include massive bleeding from the mucosa or from fistulization into a major vessel, esophageal obstruction, and fistulization into the trachea. Coexistent hiatal hernia, esophageal spasm, achalasia, and esophagogastroduodenal ulceration are common. Although the Zenker’s diverticulum can reach sizes of 15 cm or more, it is rarely palpable 7.

Squamous cell carcinoma within a Zenker’s diverticulum is extremely rare, occurring in 0.3% of Zenker diverticula worldwide. A Mayo Clinic review suggests an incidence of 0.48% in the United States. Approximately 50 cases of invasive squamous cell carcinoma and carcinoma in situ are reported in the literature. This possibility should be considered when evaluating patients with cervical metastatic squamous cell carcinoma with an unknown primary cancer 8.

Zenker’s diverticulum diagnosis

Patients with difficulty swallowing should have a thorough evaluation beginning with a history specifically attempting to identify the symptoms described above. These symptoms are considered diagnostic. After a history, the patient should undergo examination of the pharynx (throat) and larynx (voice box). This examination can be accomplished with either a flexible telescope through the nose (flexible endoscopy) or a rigid telescope or mirror (indirect laryngoscopy) through the mouth. The purpose of this exam is to identify patterns of pooling of secretions in the throat and to examine the strength of the tongue and throat muscles.

Since Zenker’s diverticulum occur in older people and because older people have weaker throat muscles and more difficulty with swallowing in general, it is critical that the physician examine the throat for overall function and health. Isolated pooling of secretions in the left side of the throat is highly associated with Zenker’s diverticulum. If the remainder of the pharynx is healthy and does not collect secretions, then it is likely that patients will do well with surgical elimination of the Zenker’s diverticulum. However, if the entire pharynx is weak, then even if the Zenker’s diverticulum is removed, the patient may still have difficulty swallowing. Therefore, patients should also undergo a radiographic assessment of swallowing that is video-taped preferably at greater than 30 frames per second. This type of recording, called a modified barium swallow will allow the surgeon to review and assess the entire swallow mechanism accurately and in detail. If the exam is recorded at less than 30 frames per second important details of the act of swallowing could be missed. This can result in performance of surgery that is not helpful because details of swallowing deficits are not identified.

Zenker’s diverticulum treatment

Zenker’s diverticulum require intervention only if it produces symptoms. In general, small (ie, < 2 cm) lesions found incidentally require no intervention. However, some surgeons contend that because these lesions are likely to become larger with time, intervention ought to be considered in younger, healthier, asymptomatic patients with Zenker’s diverticulum. Surgery is the standard of treatment, but for older or infirmed patients, life style and dietary modifications can be considered.

Small lesions are satisfactorily treated with a cricopharyngeus myotomy with or without an invagination procedure. Intermediate and large diverticula (ie, 2-6 cm) are best managed with open diverticulectomy with cricopharyngeus myotomy or by endoscopic diverticulotomy. Very large diverticula (ie, >6 cm) are best managed with excision with cricopharyngeus myotomy or a diverticulopexy with cricopharyngeus myotomy, depending on the health of the patient. Some surgeons placed a gastrostomy as the sole form of intervention for an ill patient aged 95 years with a 20-cm Zenker’s diverticulum.

Dietary modifications

Since most symptoms occur due to retained solid foods, patients can choose to adopt a pureed or full-liquid diet. By working with a dietician, meals can be made to be enjoyable and to provide enough caloric intake to maintain weight and a good quality of life. Patients who choose this option will likely still cough on retained secretions and be at increased risk of aspiration and pneumonia. Therefore, they must be instructed on oral hygiene measures. They need to eat slowly so that food does not build up in the diverticulum. The patient should also be instructed to reduce the bacterial count in their mouth by brushing their teeth before and after every meal. In this manner if or when food is aspirated, it will be less likely to bring harmful bacteria into the lungs.

Nonoperative intervention

Nonoperative management may be undertaken in patients with Zenker’s diverticulum of under 1 cm, the surgeon may elect to follow these patients so that they can be assessed for the development of symptoms or enlargement of the diverticulum or in patients with medical comorbidities precluding surgery 9.

As with cricopharyngeus achalasia, botulinum toxin may be used to provide temporary relief of dysphagia symptoms. Symptomatic patients who are poor surgical risks and have small Zenker diverticula may be treated satisfactorily by this method.

Zenker’s diverticulum surgery

Patients with preserved pharyngeal strength and swallow reflexes are excellent candidates for surgical correction. Since the main reason the Zenker’s diverticulum forms is failure of relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle, surgeons have found that surgical intervention is most effective when it targets cutting the cricopharyngeus muscle. Historically surgeons attempted to suspend the Zenker’s diverticulum or cut it out, but did not address the cricopharyngeus muscle. These procedures led to a high rate of recurrent symptoms. Subsequently surgeons began cutting the cricopharyngeus muscle. Originally cricopharyngeus myotomy was performed through and incision in the neck. While this is still a viable option and is associated with highest long-term success rate of surgery, , especially for patients with larger diverticulum, it is associated with a higher rate of complications such as vocal fold nerve paralysis, infection and esophageal perforation as well as a prolonged postoperative healing phase.

For patients requiring surgery, minimally invasive surgery is now the preferred first line approach. In this surgery, the cricopharyngeus muscle is cut by approaching it through the mouth. When performed carefully by a surgeon experienced in minimally invasive approaches, the surgery has at least an 85% long-term success rate for relief of symptoms. These minimally invasive approaches can be successful for patients with small and large diverticulum provided the surgeon understands the nuances involved with modifications for large and small diverticulum. With minimally invasive approaches, an incision in the neck is not needed, the vocal fold nerves are not placed at risk and patients can usually be home and a soft diet after only one night in the hospital. In addition, if the patient is in the 15% who have recurrent symptoms, the minimally invasive approach can often be revised or an open approach can be undertaken.

Zenker’s diverticulum prognosis

Zenker’s diverticulum prognosis is varied and dependent on multiple factors that include patients age, comorbidities and the surgical procedure performed. Since Zenker’s diverticulum is mainly a disease of the elderly, the prognosis is typically poor, and recurrence rates are high 1. Patients who undergo diverticulectomy with cricopharyngeus myotomy, immediate symptoms relief occurred in 90% to 100% of patient. The long-term symptoms recurrent rate is 2% to 33%. Mortality occurs in zero to 9.5% of these patients while morbidity, which includes mediastinitis, esophageal stenosis, recurrent laryngeal nerve damage, pharyngocutaneous fistula, hematoma and esophageal perforation occurs in 4% to 47% of patients who underwent this procedure. In patients who received treatment via endoscopic diverticulectomy with a stapler, the immediate symptoms relief occurred in 94% to 100% of patients. The long-term symptoms recurrence rate ranges from zero to 47%. Mortality occurs in zero to 1% and morbidity, which includes recurrent laryngeal nerve damage, bleeding, mediastinitis, dental injury, esophageal perforation, diverticulum perforation, and cervical emphysema occurred in 10% to 31%.

References- Nesheiwat Z, Antunes C. Zenker Diverticulum. [Updated 2019 Mar 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499996

- Achille G, Castellana M, Russo S, Montepara M, Giagulli VA, Triggiani V. Zenker Diverticulum: A Potential Pitfall in Thyroid Ultrasound Evaluation: A Case Report and Systematic Review of Literature. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2019;19(1):95-99.

- Beard K, Swanström LL. Zenker’s diverticulum: flexible versus rigid repair. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(Suppl 2):S154–S162. doi:10.21037/jtd.2017.03.133 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5384898

- Watemberg S, Landau O, Avrahami R. Zenker’s diverticulum: reappraisal. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996 Aug. 91(8):1494-8.

- Zenker diverticulum. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/zenker-diverticulum-6

- Zenker Diverticulum. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/836858-overview

- Sen P, Kumar G, Bhattacharyya AK. Pharyngeal pouch: associations and complications. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006 May. 263(5):463-8.

- Bradley PJ, Kochaar A, Quraishi MS. Pharyngeal pouch carcinoma: real or imaginary risks?. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999 Nov. 108(11 Pt 1):1027-32.

- Nemechek AJ, Amedee RG. Zenker’s diverticula. J La State Med Soc. 1996 Feb. 148(2):49-53.