Floating knee

Floating knee also referred to as ipsilateral fractures of the femur and tibia, is a flail knee joint resulting from fractures of the shafts or adjacent metaphyses of the femur and ipsilateral tibia 1. Fractures can occur anywhere along the femur and the tibia and must occur in both bones to be considered a floating knee injury 2. The term floating knee refers to the knee joint and not necessarily the connection to either long bone 3. Floating knee injuries may include a combination of diaphyseal, metaphyseal, and intra-articular fractures (see Figure 1 below) 4. This combination of fractures is less common in the pediatric population than in adults. However, epiphyseal injury can adversely affect open growth plates, predisposing a child to limb-length discrepancy and angular deformities.

Floating knee injury is generally caused by high-energy trauma 5. Local trauma to the soft tissues is often extensive, and life-threatening injuries to the head, chest, or abdomen may also be present 6.

An initial evaluation to determine the extent of a patient’s injuries is of critical importance. This evaluation should be followed by an appropriate sequence of emergency diagnostic and therapeutic measures.

The complication rate associated with floating knee injuries remains high, regardless of the treatment regimen used. Infection, nonunion, malunion, and stiffness of the knee are all common. These complications can lead to functional impairment and frequently cause unsatisfactory results.

Floating knee classification

Floating knee also known as “flail knee” injuries have been classified using various classification systems including the first classification used by Blake and McBryde, the Letts-Vincent, and the Bohn-Durbin classification systems 3.

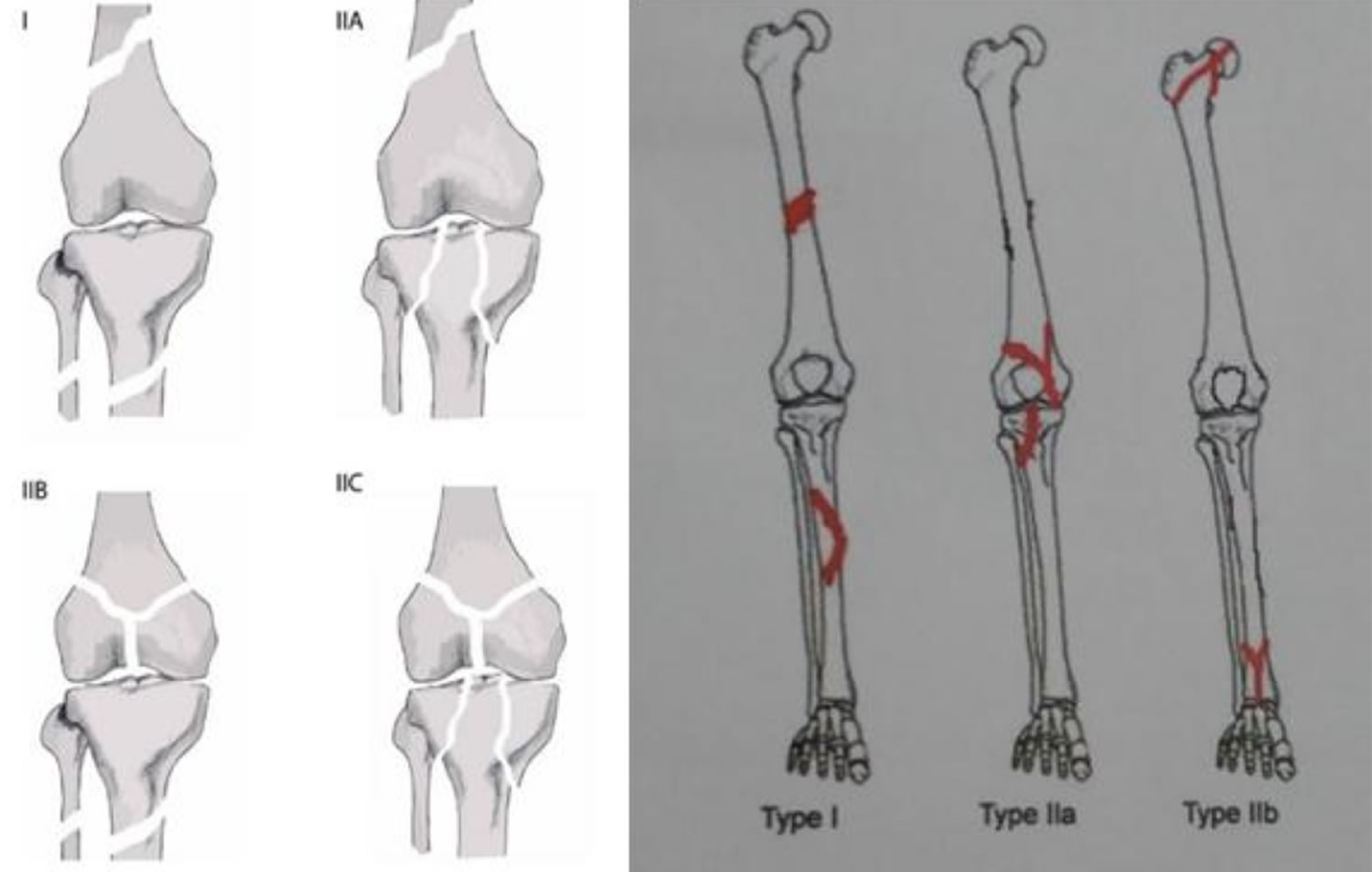

Blake and McBryde first classified the injuries based on the injury sites as type I, type II-A, and II-B 7:

- Type I fractures include fractures of both shafts of the two long bones.

- Type II is a fracture that extends into the knee, hip, or ankle joint 8

- Type II-A involves the knee joint,

- Type II-B fractures require the involvement of the hip or ankle joints .

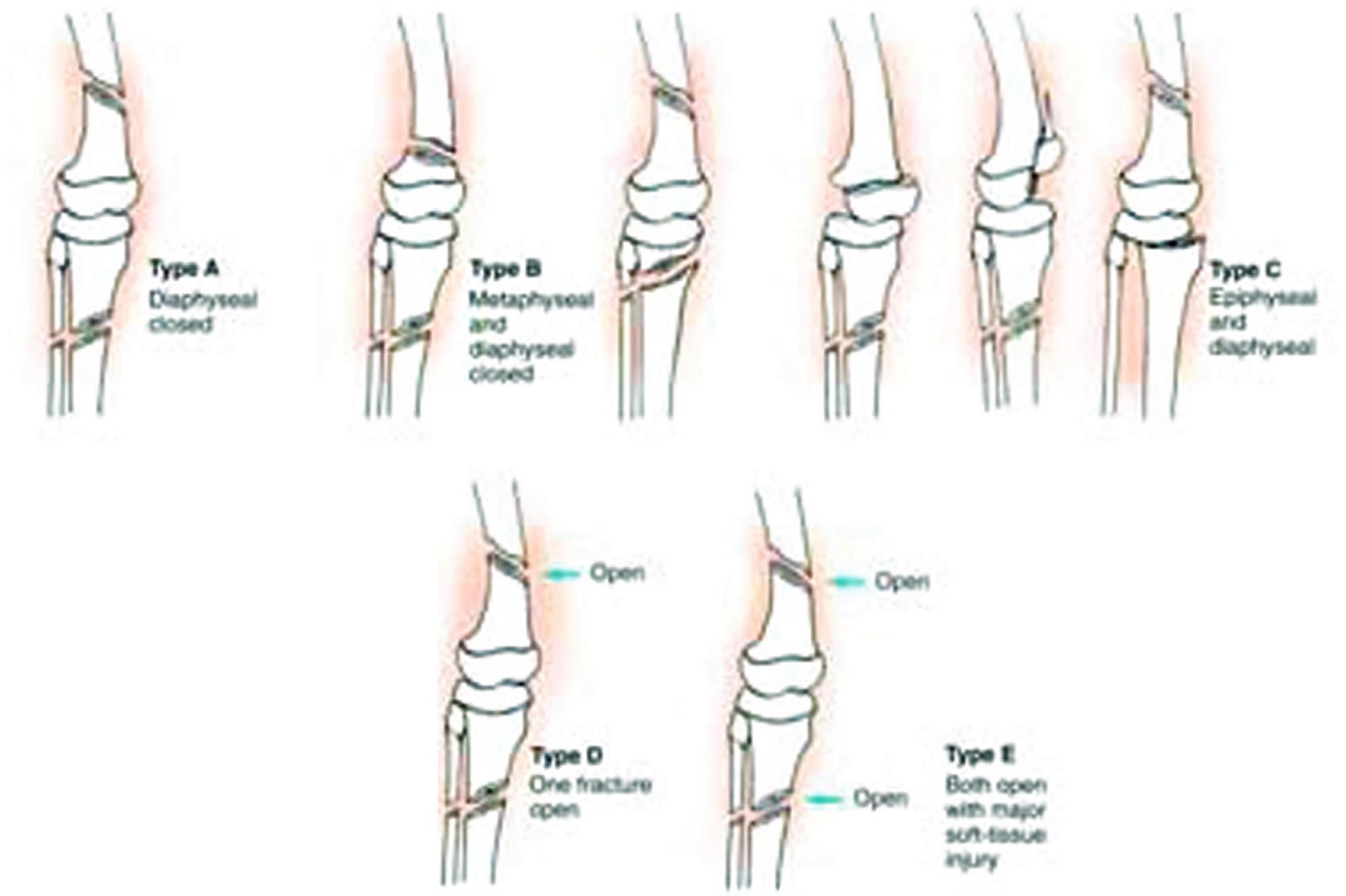

The Letts-Vincent and the Bohn-Durbin are pediatric classification systems that first classify the region of the fracture and whether it is an open or closed fracture.

Letts-Vincent classifies the fractures A-E:

- Type A fractures being two closed diaphyseal fractures

- Type B injuries are composed of two closed fractures with one being diaphyseal and the other metaphyseal

- Type C injuries include two closed fractures with one being diaphyseal and the other epiphyseal

- Type D injuries have at least one open fracture

- Type E fractures are composed of both fractures open.

Bohn-Durbin classification has three types 9:

- Type I are double shaft fractures,

- Type II injuries are juxta-articular, and

- Type III have an epiphyseal component.

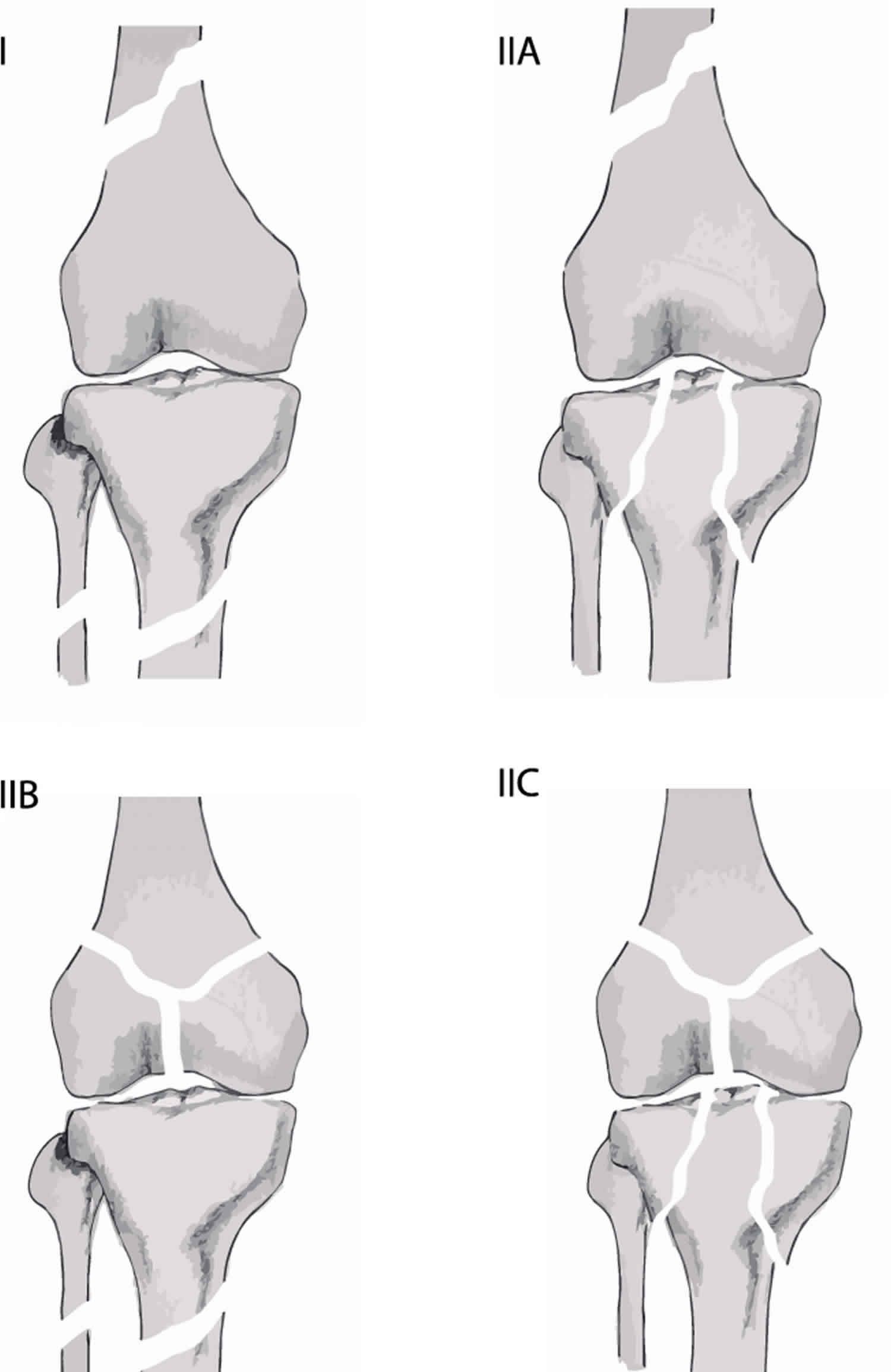

Fraser et al. 10 further classify floating knee injuries as:

- Type I: shaft fractures of both bones without the involvement of either fracture into the knee,

- Type II fractures extended into the knee and were further sub-divided.

- Type IIa involved the tibial plateau,

- Type IIb included the distal femur into the knee, and

- Type IIc involved both the tibial plateau and the distal femur within the knee joint.

Figure 1. Floating knee classification (Blake and McBryde classification)

Figure 2. Floating knee classification (Letts and Vincent classification)

Floating knee causes

As with most complex fractures, floating knee injuries are associated with high-velocity mechanisms and often accompanied by other injuries to other parts of the body, including severe soft tissue injury. These high-velocity mechanisms include: motor vehicle accidents, falls from an extreme height, pedestrian vs. auto accidents, cyclist vs. auto accidents, and other mechanisms that involve blunt trauma to the area 9.

Floating knee symptoms

Patients with floating knee injuries typically will have incurred multiple trauma injuries to that region and should not be overlooked. Furthermore, patients will most likely present with a history of trauma — for example, a motor vehicle accident (MVA), a fall from a height, pedestrian vs. auto, etc. Patients with an isolated floating knee injury will present with complaints of severe leg pain, inability to bear weight, and potentially some knee instability (due to ligamentous disruption which often accompanies these injuries). On physical examination, there will usually be tenderness to palpation at both the tibial and femoral fracture sites along with gross deformities and shortening of the affected limb. More advanced classification fractures may also be present in one or more of the fractured components. The neurovascular status may or may not be compromised and requires a thorough examination.

Floating knee complications

Malunion is always a possible complication of fractures. With floating knee injuries, the patient also runs the risk for limb length discrepancies whether that be due to lengthening or shortening of the affected limb. Limb length discrepancies may also occur in skeletally immature individuals if there is disruption of the growth plate resulting in premature physeal closure. Open fractures carry an increased risk of infection. Infection is also a complication anytime a patient undergoes a surgical procedure 9. Other complications found to occur with floating knee injuries include compartment syndrome, loss of joint motion, and requirement of limb amputation.

Complication rate decreases when one or both of the fractures are in the femoral and tibial diaphysis 11. One study found treatment with a retrograde intramedullary nail (distal to proximal insertion through the knee joint), resulted in an increased risk of heterotopic ossification around the knee compared to anterograde femoral nails (proximal to distal insertion through the proximal aspect of the femur). The explanation for this result is the fact that anterograde femoral nails never penetrate the knee joint 12.

Floating knee diagnosis

Patients with floating knee injuries should undergo evaluation according to standard protocols for trauma and as per clinical presentation. If polytrauma was involved, then the basic Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol should be implemented first. Therefore, most urgent needs should be addressed first before any intervention elsewhere, which includes examining the patient’s airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure to harmful substances or situations (ABCDE’s). Generally, standard trauma workup will be a requirement in most instances and stabilization of a critically ill patient will need to be first before any intervention to musculoskeletal complaints. Once the patient is stable, and other life-threatening injuries have been dealt with or ruled out, focusing on other injuries such as the floating knee is then indicated.

Ensuring the patient is neurovascularly intact is one of the most important things for which to check. Examining sensation in all dermatomes of the lower extremity as well as pulses of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial artery should be tested first after addressing any circulation matters. Posterior displacement of the distal femur may also cause damage to the adjacent popliteal artery. If this is suspected, a Doppler ultrasound should be conducted to rule out intimal tears.[6] Monitoring patients for signs of fat embolism are in order due to the significant skeletal trauma that usually accompanies these injuries. If any sign of fat embolism is detected, postponement of the surgical management of the fractures is necessary until the patient is stable 11.

Imaging in the form of plain film radiograph is the best initial tool for diagnosis. X-rays will allow an initial gestalt view of the affected limb to rule in/out any obvious fractures. CT scan is a diagnostic option to further investigate any complicated fractures, including the severity of comminution and bone loss and can assist in the planning of fixation techniques and predicting any complications that may arise. Due to the high incidence of ligamentous injuries associated with floating knee type injuries, an MRI may also be necessary 13.

Floating knee treatment

Treatment and management of the floating knee injury and each fracture is dependent upon multiple variables and factors. It depends on whether the fracture is open or closed, the type of fracture pattern, the location of the fracture, comminution of fracture, as well as skeletal maturity. Skeletally immature patients are more likely to be treated non-operatively with a long leg cast than skeletally mature patients with minimally displaced fractures 9. ‘Pediatric floating knee,’ classified as isolated physeal fractures of the distal femur and proximal tibia may be treated operatively by fixation with K-wires followed by casting for six weeks 14.

Other, more complicated fractures may require more invasive procedures. Femur fractures are typically treated surgically using one of three options. These are intramedullary nailing, compression plate screws, or dynamic condylar screws. Intramedullary nailing is typically the choice for diaphyseal fractures where a functional reduction is more indicated. This approach allows for stability of the fracture while still allowing for callus formation that occurs with secondary bone healing. Compression plate screws may are useful for femoral shaft fractures that require a more anatomic reduction and primary bone healing; this would occur in areas where concern for joint mobility post-operatively exists. Dynamic condylar screws were the choice in intra-articular fractures where an anatomic reduction is a must for maintaining joint mobilization.

Tibial fractures are also treated based on the above variables. External fixation is the most common option with open tibial fractures. Plate screws or locked intramedullary nails are a possible choice for most other tibial fractures. The tibia typically only requires a functional reduction unless the fracture is intra-articular (the tibial plateau). Intramedullary nailing of both bones, when possible, is the best surgical management associated with good outcomes 11.

Floating knee prognosis

According to the study by Kulkarni et al. 15, the average union time for tibial and femur fractures in floating knee injuries was 9.52 (+/-6.6) and 10.5 (+/-7.37) months respectively in a population of 89 patients aged 34.34 (+/- 12.28) years. Segmental femur fractures showed a delay in union time by about six months. This delay did not manifest in segmental tibial fractures. Over 50% of these patients had either an excellent or good outcome. Factors accounting for poor outcomes included open tibial fractures and those that required external fixation, segmental fractures, fractures involving the articular surface of the knee joint, and the requirement of additional surgeries to address the injuries. Patients with operative treatment were found to have statistically significant shorter hospital stays than those treated conservatively 7.

References- Chavda AG, Lil NA, Patel PR. An approach to floating knee injury in Indian Population: An analysis of 52 patients. Indian J Orthop. 2018 Nov-Dec. 52 (6):631-637.

- Muñoz Vives J, Bel JC, Capel Agundez A, Chana Rodríguez F, Palomo Traver J, Schultz-Larsen M, Tosounidis T. The floating knee: a review on ipsilateral femoral and tibial fractures. EFORT Open Rev. 2016 Nov;1(11):375-382.

- Card RK, Lowe JB, Bokhari AA. Floating Knee. [Updated 2019 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537096

- Rethnam U, Yesupalan RS, Nair R. Impact of associated injuries in the floating knee: a retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009 Jan 14. 10:7.

- Blake R, McBryde A Jr. The floating knee: Ipsilateral fractures of the tibia and femur. South Med J. 1975 Jan. 68 (1):13-6.

- Eone DH, Lamah L, Bayiha JE, Ondoa DL, Nonga BN, Ibrahima F, et al. [Assessment of concomitant floating knees injuries severity]. Pan Afr Med J. 2016. 25:83.

- Blake R, McBryde A. The floating knee: Ipsilateral fractures of the tibia and femur. South. Med. J. 1975 Jan;68(1):13-6.

- Hung SH, Lu YM, Huang HT, Lin YK, Chang JK, Chen JC, et al. Surgical treatment of type II floating knee: comparisons of the results of type IIA and type IIB floating knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007 May. 15 (5):578-86.

- Anari JB, Neuwirth AL, Horn BD, Baldwin KD. Ipsilateral femur and tibia fractures in pediatric patients: A systematic review. World J Orthop. 2017 Aug 18;8(8):638-643.

- Fraser RD, Hunter GA, Waddell JP. Ipsilateral fracture of the femur and tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978 Nov;60-B(4):510-5.

- Hegazy AM. Surgical management of ipsilateral fracture of the femur and tibia in adults (the floating knee): postoperative clinical, radiological, and functional outcomes. Clin Orthop Surg. 2011 Jun;3(2):133-9.

- Kent WT, Shelton TJ, Eastman J. Heterotopic ossification around the knee after tibial nailing and ipsilateral antegrade and retrograde femoral nailing in the treatment of floating knee injuries. Int Orthop. 2018 Jun;42(6):1379-1385.

- Carta S, Riva A, Fortina M, Colasanti GB, Meccariello L. The Challenges of the Femoral Bone Loss in the Management of the Floating Knee IIB According Fraser: A Case Report. J Orthop Case Rep. 2018 Jan-Feb;8(1):3-7.

- Othman Y, Hassini L, Fekih A, Aloui I, Abid A. Uncommon Floating Knee in a Teenager: A Case Report of Ipsilateral Physeal Fractures in Distal Femur and Proximal Tibia. J Orthop Case Rep. 2017 May-Jun;7(3):80-83.

- Kulkarni MS, Aroor MN, Vijayan S, Shetty S, Tripathy SK, Rao SK. Variables affecting functional outcome in floating knee injuries. Injury. 2018 Aug;49(8):1594-1601.