Fluid replacement therapy

Fluid replacement therapy is treatment to replace fluids that are lost from your body because of surgery, injury, dehydration, disease, or other conditions.

Hospitalised patients need intravenous (IV) fluid and electrolytes for one or more of the following reason (the 4Rs) 1:

- Fluid resuscitation: IV fluids may need to be given urgently to restore circulation to vital organs following loss of intravascular volume due to bleeding, plasma loss, or excessive external fluid and electrolyte loss, usually from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, or severe internal losses (e.g. from fluid redistribution in sepsis).

- Routine maintenance: IV fluids are sometimes needed for patients who simply cannot meet their normal fluid or electrolyte needs by oral or enteral routes but who are otherwise well in terms of fluid and electrolyte balance and handling i.e. they are essentially euvolaemic, with no significant deficits, ongoing abnormal losses or redistribution issues. However, even when prescribing IV fluids for more complex cases, there is still a need to meet the patient’s routine maintenance requirements, adjusting the maintenance prescription to account for the more complex fluid or electrolyte problems. Estimates of routine maintenance requirements are therefore essential for all patients on continuing IV fluid therapy.

- Replacement: In some patients, IV fluids to treat losses from intravascular and or other fluid compartments, are not needed urgently for resuscitation, but are still required to correct existing water and/or electrolyte deficits or ongoing external losses. These losses are usually from the gastrointestinal or urinary tract, although high insensible losses occur with fever, and burns patients can lose high volumes of what is effectively plasma. Sometimes, these deficits have developed slowly with associated compensatory adaptations of tissue electrolyte and fluid distribution that must be taken into account in subsequent replacement regimens (e.g. cautious, slow replacement to reduce risks of pontine demyelinosis).

- Redistribution: In addition to external fluid and electrolyte losses, some hospital patients have marked internal fluid distribution changes or abnormal fluid handling. This type of problem is seen particularly in those who are septic, otherwise critically ill, post-major surgery or those with major cardiac, liver or renal co-morbidity. Many of these patients develop oedema from sodium and water excess and some sequester fluids in the gastrointestinal tract or thoracic/peritoneal cavities.

Deciding on the optimal amount, composition and rate of administration of IV fluids to address these often complex needs is inherently difficult yet assessment, prescribing and monitoring of IV fluids in general admission and ward areas of hospitals, is often left to junior doctors and hard-pressed nurses who may lack required training and competence 2. Evidence suggests that mismanagement of fluids is common, particularly in general ward areas with the potential for adverse outcomes including excess morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospital stays and increased costs 3.

There is, therefore, a clear need for guidance on IV fluid prescribing applicable to general ward areas but since most randomized controlled trials of IV fluid therapy have examined narrow clinical questions in intensive care or intra-operative settings, many recommendations for more general use must be based on first principles. All health professionals involved in prescribing and administering IV fluids need to understand these principles if they are to prescribe and manage IV fluid therapy safely and effectively.

The most appropriate method of fluid and electrolyte administration is the simplest, safest and effective. The oral route should be used whenever possible and IV fluids can usually be avoided in patients who are eating and drinking. The possibility of enteral tube administration should also be considered if safe oral intake is compromised but there is enteral tube-accessible GI function.

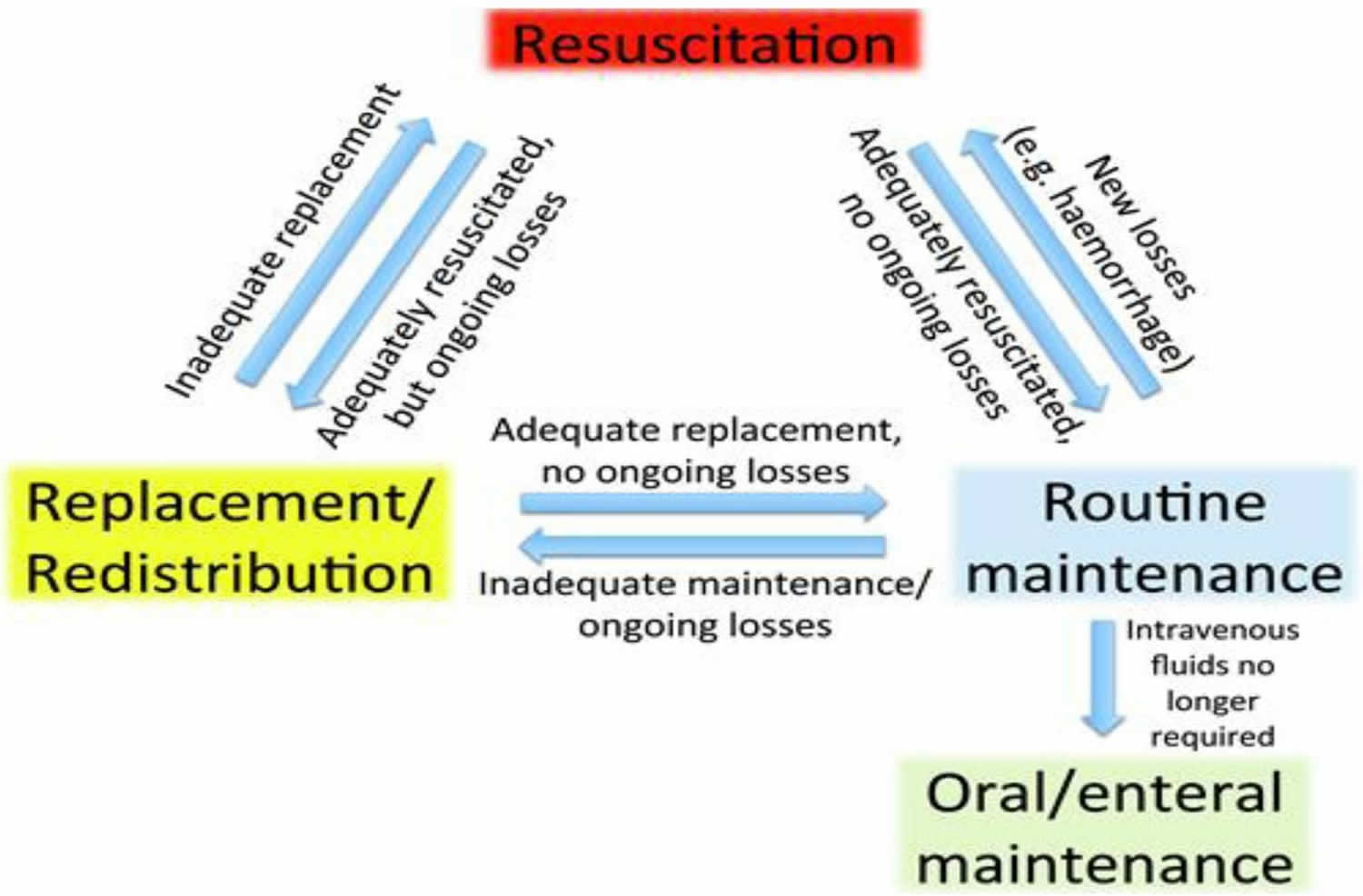

Figure 1 illustrates the ‘4 Rs’ that underpin the clinical approach to deciding IV fluid needs: Resuscitation, Routine maintenance, Replacement and Redistribution. There is also a ‘5th R’ for Reassessment.

Clinical considerations around the ‘4Rs’ can be complex and so decisions on the optimal amount, composition and rate of IV fluid administration must be based on careful, individual patient assessment. However, the clinical principles underlying these decisions can be approached as a series of questions.

Figure 1. The 4 Rs – Resuscitation, Routine maintenance, Replacement and Redistribution (5th R – Reassessment is also a critical element of care)

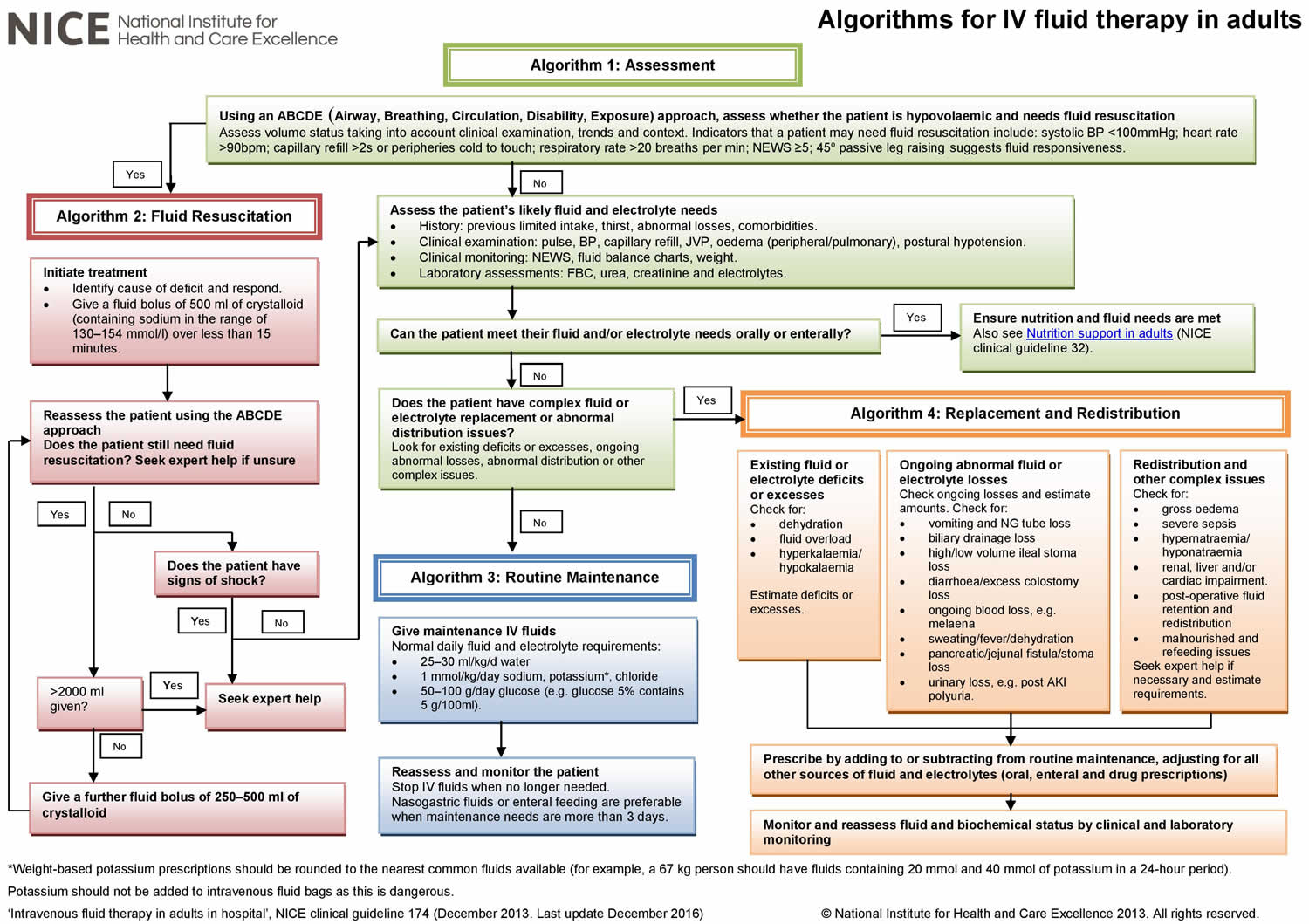

Figure 2. Fluid replacement therapy algorithm

Intravenous fluid therapy for fluid resuscitation

Urgent fluid resuscitation is needed if a patient has lost enough fluid either acutely or chronically to start showing signs of decompensation. Sympathetic responses attempt to compensate for the decrease in intravascular volume by prioritising blood flow to vital organs. The heart rate is usually increased (tachycardia) and peripheral vasoconstriction increases diastolic blood pressure. and the total effective intravascular volume is reduced by vasoconstriction. The tachycardia and reduced peripheral perfusion is followed by a marked decrease in systolic blood pressure when more than 30–40% of the intravascular volume has been lost. The changes are therefore manifest by tachycardia and reduced peripheral perfusion and as the volume deficit increases, an increasingly marked fall in blood pressure with dysfunction of most organ systems. Central nervous system depression causes agitation, confusion or decreased level of consciousness, renal hypo-perfusion causes oliguria and general tissue hypo-perfusion causes acidosis, often with compensatory tachypnoea.

Shock is defined as ‘a life threatening condition with generalized maldistribution of blood flow causing failure to deliver and/or utilize adequate amounts of oxygen, leading to tissue dysoxia. ’. It is always better to prevent shock and prevent any signs of end organ failure.

The presence of two or more of the following is likely to indicate shock 5.

- Pulse rate > 20 bpm above baseline

- Systolic BP 20 mmHg less than normal

- Capillary refill greater than 2 seconds

- Respiratory rate > 20 per minute

- Urine output less than 0.3 ml/kg/h

The presence of organ dysfunction is also suggested by metabolic acidosis, increased plasma lactate values and a central venous oxygen saturation of <70%.

There is a wide range in the ability of patients to compensate for fluid loss. Patients with significant co-morbidities and those taking cardiovascular drugs, for example, may decompensate with relatively little fluid loss. Young, very fit patients will compensate for much greater loss of intravascular volume and their systolic blood pressure may be preserved until severe shock has ensued.

In the UK, the recent adoption of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) provides a basic universal method to identify the signs of physiological decompensation.95 NEWS is derived from six physiological parameters: respiratory rate, arterial blood oxygen saturation, temperature, systolic blood pressure, pulse rate and level of consciousness; an adjustment is made for patients receiving oxygen therapy. The aggregate score triggers a response from nursing and/or medical staff depending on the thresholds set by local policy.

Treatment of shock requires urgent intravenous fluid infusion to restore intravascular volume, reverse decompensation and restore organ perfusion. Other immediate measures may also be needed, including high-flow oxygen, leg raising/head down tilt, the use of inotropes and specific measures to treat the original cause of hypovolaemia, but these are beyond the scope of this guidance.

Although it is critical that adequate fluid is given to restore and then maintain intravascular volume, it is important to avoid fluid and/or electrolyte overload. Modifying and monitoring the intravascular volume is relatively easy but this is much more difficult for the interstitial and intracellular fluid compartments. The amount of fluid needed for resuscitation is extremely variable and so frequent reassessment is needed.

Children and adults who are severely dehydrated should be treated by emergency personnel arriving in an ambulance or in a hospital emergency room. Salts and fluids delivered through a vein (intravenously) are absorbed quickly and speed recovery. The initial goal of treating dehydration is to restore intravascular volume. The simplest approach is to replace dehydration losses with 0.9% saline. This ensures that the administered fluid remains in the extracellular (intravascular) compartment, where it will do the most good to support blood pressure and peripheral perfusion.

Therapy may be started with a rapid bolus of 0.9% saline to combat incipient shock. But correction of dehydration has to be accompanied by provision of maintenance fluid- after all, the child is breathing, losing free water through the skin, and is urinating! As discussed earlier, maintenance fluid is provided as D5 0.18% or D5 0.3% saline. The combination of 0.9% saline (dehydration correction) and 0.18% saline (maintenance fluid) averages to approximately 0.45% (half-normal) saline. This approximation is acceptable because the kidneys will sort out what to keep and what to excrete.

A typical sequence of events in the management of a child with 10% dehydration AND A NORMAL SERUM sodium (Na) LEVEL is given below. Management of children with a serum sodium level of < 135 or> 145 mEq/L is beyond the scope of this discussion.

- Step 1: In the emergency room, the child is estimated as having 10% dehydration. The blood pressure is low and the heart rate is very high. This child is in shock. The goal is to rapidly stabilize the vital signs; maintenance fluid is not a consideration at this time. The child is given a 20 ml/kg bolus of 0.9% saline over 10-20 minutes. The vital signs stabilize (the bolus can be repeated if necessary).

- Step 2: the patient is transferred to the inpatient unit. By this time, serum electrolytes levels are available and the serum sodium concentration is within the normal range. Subsequent fluid therapy is calculated as follows:

- This child’s total fluid loss was 10% of 10 kg, or 1000 ml. Of this, 200 ml has already been infused in the emergency room, so the remaining deficit is 800 ml.

Typically, half the total deficit is replaced in the first eight hours after admission and the remaining fluid is given over the next 16 hours. So, this child needs 300 ml of 0.9% saline in the next eight hours (for a total of 500 ml) and another 500 ml in the next 16 hours.

However, maintenance fluid also has to be administered. The volume of maintenance fluid for 24 hours is 1000 ml (100 ml/kg X 10 kg). This needs to be given as D5 0.33% saline.

Note #1: Once the child has started urinating, KCl should be added to the intravenous fluids at a concentration of 20 mEq/L.

Note #2: If the child continues to vomit or have significant diarrhea, the volume of ongoing fluid loss should be estimated and added to the deficit every few hours as 0.9% saline. Ideally, the diapers should be weighed. If this is not possible, then a volume of 50-100 ml should be used for each stool in an infant and 100-200 ml for the older child.

Note #3: The dehydration component of fluid replacement MUST be provided as 0.9% saline. NEVER use a hypotonic saline, such as D5 0.18% (fifth-normal saline), D5 0.3% (third-normal saline) or even D5 0.45% (half-normal saline) to correct dehydration. Dehydration and hypovolemia result in secretion of anti-diuretic hormone, which causes retention of free water, and provision of hypotonic replacement fluid can lead to potentially life-threatening hyponatremia.

Now the fluid calculation looks like this:

Table 1. Fluid replacement therapy (IV)

| 0-8 hours | 9-24 hours | |

|---|---|---|

| Deficit | 300 ml of 0.9% saline | 500 ml of 0.9% saline |

| Maintenance | 333 ml of D5 0.33% saline | 666 ml of D5 0.18% saline |

| Averaged total | 663 ml of D5 0.45%normal saline | 1166 ml of D5 0.45% normal saline |

- Step 3: Suppose the child is well hydrated by the second hospital day, but is still feeling queasy and does not want to drink. Maintenance fluids can now be continued as D5 0.33% or D5 0.50% saline with 20 mEq/L of KCl.

Some words of caution:

In the past decade, there have been a number of case reports of patients developing dangerous hyponatremia during intravenous fluid therapy. To avoid this,

- As discussed above, use ONLY normal saline for volume replacement. Never use hypotonic saline; these patients are secreting antidiuretic hormone (ADH) which can lead to water retention. The appropriate volume of normal saline can be combined with the hypotonic saline being used for provision of maintenance fluid requirements so that the final solution is D5 0.45% normal saline.

- NEVER use excessive volumes of hypotonic saline as a maintenance fluid. Calculate the requirement, and don’t exceed it!

- If the serum sodium is dropping below 138 mEq/L, switch to normal saline for rehydration and maintenance.

- If a patient is suspected to have the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), use only normal saline for rehydration and maintenance.

- Post-operative patients have a tendency for SIADH. These patients should receive only normal saline, even for maintenance.

Hyperatremia and hyponatremia

The blood brain barrier prevents rapid movement of solutes out of, or into, the brain. On the other hand, water can move freely across the blood brain barrier. Rapidly developing hyponatremia causes a shift of water into the brain; conversely, hypernatremia can lead to brain dehydration and shrinkage.

Severe, acute hyponatremia may result in brain edema with neurological symptoms such as a change in sensorium, seizures, and respiratory arrest. This is a life-threatening medical emergency and requires infusion of hypertonic saline.

Acute hypernatremia results in a reduction in brain volume. This can lead to subdural bleeding from stretching and rupture of the bridging veins that extend from the dura to the surface of the brain.

Given time, the brain can alter intracellular osmotic pressure to better match plasma osmolality.

With persistent or slowly developing hyponatremia, brain cells extrude electrolytes and organic osmoles and the increase in brain volume is blunted or avoided. Neurologic symptoms are absent or subtle.

With persistent hypernatremia, brain cells generate organic osmoles (also known as idiogenic osmoles) to compensate for the increase in plasma osmolality. Again, the change in brain volume is partially blunted. These processes take 24-48 hours to become effective and leave the brain with a decreased (in hyponatremia) or increased (hypernatremia) osmolar content.

Just as the adaptation takes 24 hours or more, un-adaptation also takes time. Rapid correction of long-standing hypo- or hypernatremia has the potential for severe neurological consequences because of sudden changes in brain volume in the opposite direction. The neurologic manifestations associated with overly rapid correction of hyponatremia is called osmotic demyelination syndrome.

So, hyper- or hyponatremia of long duration should be corrected slowly.

Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia is defined as serum sodium (Na) < 135mmol/L.

- Most children with sodium (Na) > 125mmol/L are asymptomatic.

Hyponatremia and rapid fluid shifts can result in cerebral edema causing neurological symptoms.

- If Na < 125mmol/L or if serum sodium has fallen rapidly vague symptoms such as nausea and malaise are more likely and may progress.

- If Na < 120mmol/L: headache, lethargy, obtundation and seizures may occur.

- Chronic hyponatremia (developing > 24 hours) may have more subtle features such as restlessness, weakness, fatigue or irritability (due to cerebral adaptation)

Rapid correction of hyponatremia can result in osmotic demyelination syndrome which manifests as irreversible neurologic features (dysarthria, confusion, obtundation and coma) which often present days after sodium correction.

Hyponatremia key points

- Prevention involves identifying children at risk (i.e. those with conditions associated with increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion) and restricting their fluid to 1/2-2/3 maintenance of isotonic solution.

- A child’s fluid status is key in determining the cause of hyponatremia and dictating treatment.

- The rate of correction of hyponatremia should not exceed 8mmol/L in 24 hours as over rapid correction can cause osmotic demyelination syndrome.

- Hyponatremic seizures and/or altered conscious state are a medical emergency and can cause irreversible neurological damage.

Table 2. Hyponatremia causes (common causes in bold)

Fluid Overloaded | Euvolemic | Dehydrated |

|

|

|

Hyponatremia prevention

Special attention should be paid when prescribing fluids to children with conditions associated with increased ADH secretion

- Only give isotonic fluid (e.g.: 0.9% Saline + 5% glucose) as maintenance fluids.

- Only give 1/2- 2/3 maintenance rate if child is euvolemic

- Measure urea and electrolytes at baseline, then monitor daily while on fluids

- Regular weights

Hyponatremia investigations

Investigations (recommended if Na < 130mmol/L)

- Paired serum and urine osmolality

- Urinary sodium

- Blood sugar level (if hyperglycemia present in addition to hyponatremia see diabetic ketoacidosis)

- Consider blood gas if sick

Hyponatremia treatment

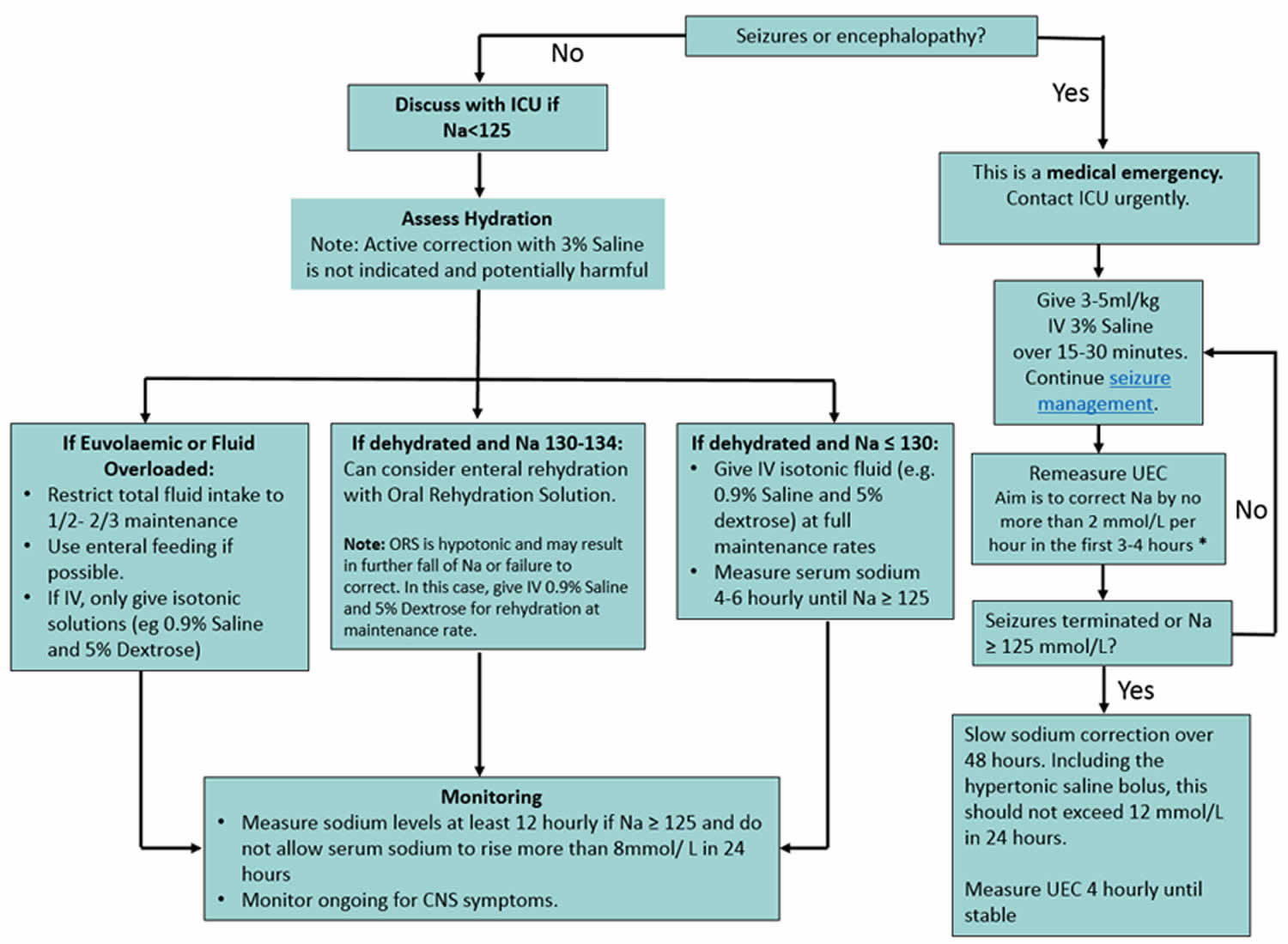

- Management is determined by presence of seizures/ altered conscious state and fluid status (see flow chart below).

- The target rate of serum sodium correction is 6-8mmol/L in 24 hours (unless seizing- see flow chart below).

- All children should have a strict fluid balance including weight (minimum daily, but maybe 6-12 hourly for more unwell children).

- Remember to treat the underlying cause.

- Consider consultation with local paediatric team when:

- Sodium level < 130mmol/L or the child is symptomatic

- Correction > 8mmol/ L in 24 hours

- Children requiring care beyond the comfort of the local hospital.

- Consider transfer when:

- Sodium < 125mmol/L

- The child has had CNS symptoms including seizures or altered conscious state

Figure 3. Hyponatremia treatment

Footnotes:

- Risk of morbidity from delayed treatment is greater than the risk of osmotic demyelination from overly rapid correction. Therefore, aggressive initial correction is indicated for the first 3-4 hours (or until symptoms resolve) at a rate not to exceed 2 mmol/L per hour

- Hyponatremic seizures may be refractory to anticonvulsants and sodium correction should not be delayed

- 3% Saline should preferably be given via a central line.

Hypernatremia

Mild hypernatremia is relatively common. Risk increases with level of serum sodium. Treatment can be complicated and potentially dangerous. Seek specialist advice early.

Table 3. Hypernatremia definition

| Definition | Serum [Na+] (mmol/l) |

| Hyponatremia | < 135 |

| Normal | 135 – 145 |

| Mild Hypernatremia | 146 – 149 |

| Moderate Hypernatremia | 150 – 169 |

| Severe Hypernatremia | ≥ 170 |

Most common causes of hypernatremia:

- Water loss in excess of sodium

- Diarrhea, especially with continuing hyperosmolar feeding/rehydration (e.g.,: Polyjoule, home-made rehydration solutions)

- Severe burns

- Inability to obtain/swallow adequate water (+/- impaired renal concentrating ability) – including neonates (e.g., inadequate breastmilk intake)

Less common: consider if not improving as expected with management

- Water deficit from

- Impaired thirst drive (e.g. Hypothalamic lesion)*

- Diabetes insipidus*

- Osmotic diuresis

- Gain of sodium

- Ingestion of large quantities of sodium (inappropriate formula concentration, high osmolarity oral rehydration solutions)

- Iatrogenic sodium administration (hypertonic saline, sodium bicarbonate)

*Endocrinology can provide advice on management of central diabetes insipidus if required.

Hypernatremia assessment

- Severe symptoms mainly develop when the serum [Na+] > 160mmol/l.

- More severe with acute hypernatremia

- Chronic hypernatremia (present > 5 days) is often well tolerated because of cerebral compensation.

- Clinical signs may lead to underestimation of true degree of dehydration. Weight loss is more reliable.

- The child may appear sicker than expected for the clinical signs of dehydration that are present.

- Shock occurs late because intravascular volume is relatively preserved.

- Look for signs of intracellular dehydration and neurological dysfunction:

- Lethargy

- Irritability

- Skin feels “doughy”

- Ataxia, tremor

- Hyperreflexia, Seizures, reduced GCS (Glasgow Coma Score)

Hypernatremia investigations

- Check other electrolytes and blood sugar. These may need concurrent management

- Investigations for rare differentials (moderate/severe hypernatremia)

- Urine sodium and osmolality (paired with serum)

- Collect at diagnosis, as may help identify rare differentials if not responding to management as expected

- If seizures / neurological signs: recheck sodium urgently, consider neuroimaging, seek specialist advice.

Hypernatremia management

Too rapid reduction of the sodium in hypernatremia can cause cerebral edema, convulsions and permanent brain injury. Close monitoring is critical.

Resuscitation:

- If “shocked”, resuscitate with boluses 20ml/kg of 0.9% saline as required.

Initial management and monitoring

Fluid management should then be based on the initial serum sodium.

- Rate to lower sodium:

- Aim to lower the serum sodium slowly at a rate of no more than 12mmol/L in 24 hours, (0.5mmol/L/hour).

- An even slower rate will be required for children with chronic hypernatremia

- The rate of rehydration, or sodium concentration of fluids, may need to be changed if appropriate rate of correction of serum sodium is not seen (too fast or too slow). Seek specialist advice.

- Stop any feed fortifications (such as extra scoops of formula or Polyjoule)

- Monitor fluid status

- urine output

- repeat weight (initially 6 hourly, esp if infants or severe hypernatremia).

- Monitor other electrolytes and blood sugar

- Measure ongoing losses (ie: vomiting or diarrhea, excluding urine) and replace ml for ml with normal saline.

- Careful neurological monitoring

When to consider transfer to tertiary center:

- Child with moderate hypernatremia where cause is unclear, or cause other than dehydration

- Any child with severe hypernatremia

- Hypernatremia not responding as expected to management

- Child requiring care beyond the comfort level of the hospital.

Rehydration

The following guide is for rehydration of patients with excess water loss for the first 12 – 24 hours.

- Mild hypernatremic dehydration, [Na+] 146 – 149 mmol/L.

- Rarely requires specific management. Manage underlying cause. Repeat in 4-6 hours if clinically indicated.

- Moderate hypernatremic dehydration, [Na+] 150 – 169 mmol/L.

- After initial resuscitation, replace the deficit plus maintenance slowly at a uniform rate over 48 hours.

- Nasogastric rehydration is preferred. Use oral solution (eg: Gastrolyte),

- Note: Gastrolyte has a low sodium concentration (60mmol/L).

- Carefully regulate fluid intake – do not allow excessive intake in a thirsty child.

- If the serum sodium falls too rapidly (>0.5mmol/L/hr) slow the rate of rehydration (for example, by 20%) or change to intravenous fluids.

- If needing intravenous rehydration use Plasma-Lyte 148 and 5% Glucose OR 0.9% sodium chloride (normal saline) and 5% Glucose. Add maintenance KCl once urine output established. See table below.

- Check urea and electrolytes and glucose hourly intially.

- If after 6 hours of rehydration therapy the sodium is decreasing at a steady rate then check the U&Es and glucose 4 hourly.

- If serum sodium is falling faster than 1 mmol/L/hr – seek specialist advice

- Severe hypernatremic dehydration [Na+] ≥ 170

- A medical emergency. Tertiary referral and contact Intensive Care for consideration of admission.

- After initial resuscitation, aim to replace deficit and maintenance with Plasma-Lyte 148 and 5% Glucose OR 0.9% sodium chloride (normal saline) and 5% Glucose over 72 – 96 hours.

Table for fluid replacement:

- Use only when hypernatremia is associated with dehydration

- This table advises starting rate, which may need to change depending on progress – seek specialist advice

- Ongoing losses (eg: profuse diarrhea) need to be replaced in addition

Table 4. Hypernatremia fluid replacement

| Weight (kg) | Moderate hypernatraemia [Na+] 150 – 169 NG: Gastrolyte OR iv: Plasma-Lyte 148 and 5% Glucose OR 0.9% sodium chloride (normal saline) and 5% Glucose Rate of fluids ml/hr (replacing deficit over 48hrs) | Severe hypernatraemia [Na+] > 170 iv: Plasma-Lyte 148 and 5% Glucose OR 0.9% sodium chloride (normal saline) and 5% Glucose Rate of fluids ml/hr (replacing deficit over 96hrs) |

| 4 | 22 | 21 |

| 5 | 27 | 25 |

| 6 | 33 | 30 |

| 7 | 38 | 35 |

| 8 | 44 | 40 |

| 10 | 55 | 50 |

| 12 | 62 | 56 |

| 14 | 68 | 62 |

| 16 | 75 | 68 |

| 18 | 82 | 75 |

| 20 | 90 | 80 |

| 22 | 96 | 87 |

| 24 | 100 | 90 |

| 26 | 105 | 95 |

| 28 | 110 | 98 |

| 30 | 114 | 100 |

| 32 | 120 | 105 |

| 34 | 124 | 110 |

| 36 | 128 | 113 |

| 38 | 133 | 117 |

| 40 | 138 | 122 |

| 45 | 150 | 132 |

| 50 | 160 | 142 |

| 55 | 175 | 152 |

| 60 | 187 | 162 |

| 65 | 195 | 168 |

| 70 | 200 | 173 |

Footnotes:

- If seizures or other signs of cerebral edema occur during treatment: recheck serum sodium urgently. Hypertonic saline may be required to partially reverse the reduction in serum sodium. Seek specialist advice.

- Seizures may be due to venous sinus thrombosis or cerebral infarction. Consider imaging with a contrast CT scan.

- Consider peritoneal dialysis if the serum [Na+] > 180mmol/l.

Stomach flu fluid replacement

Stomach flu is commonly known as viral gastroenteritis or ‘gastro’ – is not a type of flu (influenza) at all (flu viruses do not cause gastroenteritis), but a common virus illness that affects your gut (stomach and intestines) that can cause vomiting and diarrhea. Gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the lining of your stomach and intestines caused by a virus, bacteria or parasites. Viral gastroenteritis is the second most common illness in the U.S. The cause is often a norovirus infection. Gastroenteritis is easily spread through contaminated food or water, and contact with an infected person (or their vomit or poop). The best prevention is frequent hand washing. Good hand washing with soap and water before food preparation and eating; and after going to the toilet, changing nappies, and handling any ill person is important in helping to stop the spread of infection.

Symptoms of gastroenteritis include diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, fever and chills. Gastroenteritis is not usually serious but it can make you very dehydrated. Milder forms can be managed at home by drinking fluids. Most people recover with no treatment.

Stomach flu (gastroenteritis) may be caused by:

- viruses (such as rotavirus or norovirus infections)

- bacteria (including salmonella)

- toxins produced by bacteria

- parasites (such as giardia)

- chemicals (such as toxins in poisonous mushrooms)

Gastroenteritis should only last for a few days. Stomach flu doesn’t usually require medication.

The most common problem with gastroenteritis is dehydration. This happens if you do not drink enough fluids to replace what you lose through vomiting and diarrhea. Dehydration is most common in babies, young children, the elderly and people with weak immune systems. Older people, young children and those with a weakened immune system are at risk of developing more serious illnesses.

It is very important to drink plenty of fluids. See a doctor immediately if your child cannot keep down a sip of liquid or has dehydration (dry mouth, no urine for 6 hours or more, or lethargy). If you are unwell with diarrhea or vomiting, you could have gastroenteritis. A doctor can diagnose gastroenteritis after talking to and examining you. If you’re not getting better, the doctor may want to do stool (poop) tests to find out what’s making you ill.

You should see your doctor if:

- your child is very young or small (aged below 6 months or weighs less than 8 kg)

- your child is born preterm, or has other chronic conditions

- your child is passing less than 4 wet nappies/day

- you or your child is passing any blood in the stool

- you or your child is having dark green (bile) vomits

- you or your child vomits blood

- you or your child is having severe abdominal pain

- you or your child less than 3 years old and has a fever more than 101.3 °F (38.5° C)

- you or your child is showing signs of dehydration (very thirsty, cold hands and feet, dry lips and tongue, sunken eyes, sunken fontanelle, sleepy or drowsy)

- you or your child is unable to tolerate any oral intake because of severe vomiting

- you or your child becomes unusually drowsy

- vomiting persists more than two days

- diarrhea persists more than several days

- diarrhea turns bloody

- lightheadedness or fainting occurs with standing

- confusion develops

- worrisome abdominal pain develops

Stomach flu symptoms

Someone with gastroenteritis may have:

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- nausea (feeling sick in the stomach)

- stomach pains

- low grade fever

- headaches

- no appetite

Vomiting often occurs at the start of the illness and may last 2-3 days. Diarrhea, which is often runny may last up to 10 days. Your child may also have a fever and abdominal (tummy) pains with the illness.

How to treat stomach flu

There’s no specific medicine for stomach flu (gastroenteritis). Antibiotics aren’t effective against viruses, and overusing them can contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria. The most important treatment for gastroenteritis is to drink fluids (see oral replacement fluid therapy below). Frequent sips are easier for young children than a large amount all at once. Keep drinking regularly even if you are vomiting.

If you have a baby or young child with gastroenteritis, it’s a good idea to have them checked by a doctor for dehydration. You can get rehydration fluids from a pharmacy. These are the best fluids to use in cases of gastroenteritis, especially for children.

If you can’t get any, or your child refuses to drink it, giving diluted fruit juice (one part juice to four parts of water) is reasonable. You could try a cube of ice or an iceblock if your child won’t drink. Avoid milk and other dairy products and do not give juice, sodas, sports drinks or other soft drinks as the sugar may make the diarrhea worse. It is fine to eat once you feel like it.

Babies can continue milk feeds throughout the illness, with rehydration fluid between feeds. Medication for nausea or diarrhea can be useful for adults, but may not be safe for kids. Antibiotics are rarely helpful.

If you are very sick with gastroenteritis, you may need to go to hospital where you may be put on a drip.

IV fluids – for children beyond the newborn period

- Whenever possible the enteral route should be used for fluids. These guidelines only apply to children who cannot receive enteral fluids.

- The safe use of IV fluid therapy in children requires accurate prescribing of fluid and careful monitoring

- Always check orders that you have written, and ensure that you double check on orders written by other staff when you take over the child’s care

- Incorrectly prescribed or administered fluids are potentially very dangerous. More adverse events are described from fluid administration than for any other individual drug. If you have any doubt about a child’s fluid orders – ask a doctor.

- Remember to check compatibility of intravenous fluid with any intravenous drugs that are being co-administered.

Assessment of fluid requirements

If required, administer an initial bolus(es) of fluid to correct intravascular depletion then: Maintenance fluids plus Deficit (dehydration guidelines) plus Ongoing losses (dehydration guidelines)

Hypovolemia

- Give boluses of 10-20ml/kg of 0.9% sodium chloride (normal saline), which may be repeated. Do not include this fluid volume in any subsequent calculations

Maintenance fluids

Maintenance fluids are used when a patient is nil per os (NPO) or nothing through the mouth. Maintenance fluids consist of water, glucose, sodium, and potassium. The glucose prevents starvation ketoacidosis and decreases the likelihood of hypoglycemia. Water, sodium and potassium protect the patient from dehydration and electrolyte disorders.

Maintenance fluids guideline should be used as a starting point and will need to be adjusted in ALL unwell children.

Generally 2/3 of maintenance rate should be used in unwell children unless they are dehydrated. This is because they are likely to be secreting anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), so will need less fluid. Children with meningitis or other acute central nervous system (CNS) conditions will likely require additional fluid restriction – seek specialist advice.

For fluid options in the dehydrated child see dehydration guidelines.

Rate of maintenance fluids

The wide variation in size of children dictates that the rate of maintenance fluids is adjusted based on the patient’s size. While there are formulas based on body surface area, weight is generally used to determine the rate of intravenous fluids. Ideal body weight (adjusting for increased adiposity) or dry weight (adjusting for volume overload or volume depletion) have theoretical advantages, but the patient’s actual weight is generally used for practical reasons. Moreover, these differences are generally clinically inconsequential given the fact that the calculated rate is an estimate that relies on normal kidney function for maintaining the patient in a euvolemic state. Table 5 provides formulas for calculating maintenance fluids as a total volume per 24 hours or as a rate per hour.

- Calculating Maintenance fluid rate: Most unwell children should have a restriced (2/3) maintenance rate prescribed. The basis from which calculations are made are detailed below

- daily fluid intake which replaces the insensible losses (from breathing, through the skin, and in the stool)

- allows excretion of the daily production of excess solute load (urea, creatinine, electrolytes, etc) in a volume of urine that is of an osmolarity similar to plasma.

- volume calculated per kilo.

Table 5. Rate of maintenance fluids

| Weight | Volume/24 hours | Rate/hour |

|---|---|---|

| 0-10 kg | 100 ml/kg | 4 ml/kg |

| 11-20 kg | 1000 ml + 50 ml/kg for each kg > 10 kg | 40 ml + 2 ml/kg for each kg >10 kg |

| >20 kg | 1500 + 20 ml/kg for each kg > 20 kg | 60 ml + 1 ml/kg for each kg >20 kg |

| Maximum | 2400-3000 ml | 100-120 ml |

Footnotes: 100mls/hour (2400mls/day) is the normal maximum amount. There is often confusion about the difference between oral and iv fluid requirements for young infants. The water requirement is identical for both routes of administration. The relatively low energy density of milk means that infants need 150-200mls/kg/day to obtain adequate nutrition. That is why they pass more dilute urine than older children.

Table 6. Maintenance fluid rates

| Weight (kg) | Full Maintenance (mL/hour) Well child e.g. fasting for theater | 2/3 maintenance (mL/hour) Most unwell children e.g., pneumonia, meningitis |

| 5 | 20 | 13 |

| 10 | 40 | 27 |

| 15 | 50 | 33 |

| 20 | 60 | 40 |

| 25 | 65 | 43 |

| 30 | 70 | 47 |

| 35 | 75 | 50 |

| 40 | 80 | 53 |

| 45 | 85 | 57 |

| 50 | 90 | 60 |

| 55 | 95 | 63 |

| 60 | 100 | 67 |

Footnote: REMEMBER to consider fluid deficit and ongoing losses – especially in severe gastroenteritis, if there are drain losses, ileostomies etc. Maintenance fluid rates are not adequate for patients with volume depletion or excessive ongoing fluid/electrolyte losses. They provide too much fluid for the patient with volume overload, especially if there is impaired kidney function.

Composition of maintenance fluids

Table 7. Some good fluid solutions for sick children

| Fluid | Alternative names | Uses |

| 0.9% sodium chloride | Normal saline | Initial boluses Replacement of deficit Replacement of losses |

| 0.9% sodium chloride and 5% Glucose +/- 20mmol/L KCl | Normal saline with glucose | Maintenance hydration |

| Plasma-Lyte148 and 5% Glucose (contains 5mmol/L of potassium) | Maintenance Replacement of deficit Replacement of losses | |

| Plasma-Lyte148 and 5% Glucose with 20mmol/L potassium (15mmol/L of KCl will need to be added to a standard bag to bring the concentration to 20mmol/L) | Maintenance hydration – should only be used for children with hypokalaemia Replacement of deficit Replacement of losses |

Footnote: Consider whether potassium is required in the fluid. This should be avoided, if possible, unless premade fluid bags containing potassium are available. Adding potassium to bags of fluid on the ward is a safety risk. Hypotonic fluid (containing a sodium concentration less than plasma) is no longer recommended in children. These fluids have been associated with morbidity/mortality secondary to hyponatraemia. Fluids that should NOT be given include: 0.18% NaCl with 4% glucose +/- KCl 20mmol/L (or 4% and 1/5 NS) should NOT be given

Special fluids

Outside the newborn period, do not use these fluids apart from exceptional circumstances and check the serum sodium regularly.

- 10% Dextrose: Used in neonates (sometimes with additional NaCl). Used in ICU for patients under 12 months (with 0.45% saline). Sometimes used by infusion in neonates and children with metabolic disorders. Check blood glucose regularly.

- 15-20% Dextrose: Very occasionally used by infusion in children with metabolic disorders. Check blood glucose regularly.

- 25% and 50% Dextrose: Rarely required in children, misuse can cause severe adverse events. Only used in discussion with senior staff as bolus or low volume infusions (1-2 ml/hr) to correct refractory hypoglycaemia.

Monitoring

- All children on IV fluids should be weighed prior to the commencement of therapy, and daily afterwards. Ensure you request this on the treatment orders.

- Children with ongoing dehydration/ongoing losses may need 6 hourly weights to assess hydration status

- All children on IV fluids should have serum electrolytes and glucose checked before commencing the infusion (typically when the IV is placed) and again within 24 hours if IV therapy is to continue.

- For more unwell children, check the electrolytes and glucose 4-6 hours after commencing, and then according to results and the clinical situation but at least daily.

- Pay particular attention to the serum sodium on measures of electrolytes. If <135mmol/L (or falling significantly on repeat measures) see Hyponatraemia Guideline. If >145mmol/L (or rising significantly on repeat measures) see Hypernatraemia guideline.

- Children on iv fluids should have a fluid balance chart documenting input, ongoing losses and urine output.

Home remedies

To help keep yourself more comfortable and prevent dehydration while you recover, try the following:

- Let your stomach settle. Stop eating solid foods for a few hours.

- Try sucking on ice chips or taking small sips of water. You might also try drinking clear soda, clear broths or noncaffeinated sports drinks. Drink plenty of liquid every day, taking small, frequent sips.

- Ease back into eating. Gradually begin to eat bland, easy-to-digest foods, such as soda crackers, toast, gelatin, bananas, rice and chicken. Stop eating if your nausea returns.

- Avoid certain foods and substances until you feel better. These include dairy products, caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, and fatty or highly seasoned foods.

- Get plenty of rest. The illness and dehydration may have made you weak and tired.

- Be cautious with medications. Use many medications, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), sparingly if at all. They can make your stomach more upset. Use acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) cautiously; it sometimes can cause liver toxicity, especially in children. Don’t give aspirin to children or teens because of the risk of Reye’s syndrome, a rare, but potentially fatal disease. Before choosing a pain reliever or fever reducer discuss with your child’s pediatrician.

For infants and children

When your child has an intestinal infection, the most important goal is to replace lost fluids and salts. These suggestions may help:

- Help your child rehydrate. Give your child an oral rehydration solution, available at pharmacies without a prescription. Talk to your doctor if you have questions about how to use it. Don’t give your child plain water — in children with gastroenteritis, water isn’t absorbed well and won’t adequately replace lost electrolytes. Avoid giving your child apple juice for rehydration — it can make diarrhea worse.

- Get your child back to a normal diet slowly. Gradually introduce bland, easy-to-digest foods, such as toast, rice, bananas and potatoes.

- Avoid certain foods. Don’t give your child dairy products or sugary foods, such as ice cream, sodas and candy. These can make diarrhea worse.

- Make sure your child gets plenty of rest. The illness and dehydration may have made your child weak and tired.

- Avoid giving your child over-the-counter anti-diarrheal medications, unless advised by your doctor. They can make it harder for your child’s body to eliminate the virus.

If you have a sick infant, let your baby’s stomach rest for 15 to 20 minutes after vomiting or a bout of diarrhea, then offer small amounts of liquid. If you’re breast-feeding, let your baby nurse. If your baby is bottle-fed, offer a small amount of an oral rehydration solution or regular formula. Don’t dilute your baby’s already-prepared formula.

Oral rehydration therapy

Oral rehydration therapy also called ORT, oral rehydration salts, oral rehydration solutions (ORS) or oral electrolyte solution, is a simple, cheap and effective treatment for diarrhea-related dehydration, for example due to cholera or rotavirus. Oral rehydration therapy consists of a solution of salts and other substances such as glucose, sucrose, citrates or molasses, which is administered orally. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) includes rehydration and maintenance fluids with oral rehydration solutions (ORS), combined with continued age-appropriate nutrition 6. Oral rehydration therapy is used around the world, but is most important in the Third World, where it saves millions of children from diarrhea where it is still the leading cause of death. Oral rehydration therapy has now become the mainstay of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) efforts to decrease diarrhea morbidity and mortality, and Diarrheal Disease Control Programs have been established in more than 100 countries worldwide 7.

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) encompasses two phases of treatment:

- The rehydration phase, in which water and electrolytes are given as oral rehydration solution (ORS) to replace existing losses, and

- The maintenance phase, which includes both replacement of ongoing fluid and electrolyte losses and adequate dietary intake 8.

It is important to emphasize that although oral rehydration therapy (ORT) implies rehydration alone, in view of present advances, knowledge, and practice, the definition has been broadened to include maintenance fluid therapy and nutrition. Oral rehydration therapy is widely considered to be the best method for combating the dehydration caused by diarrhea and/or vomiting.

Human survival depends on the secretion and reabsorption of fluid and electrolytes in the intestinal tract. The adult intestinal epithelium must handle 6,500 mL of fluids/day, consisting of a combination of oral intake, salivary, gastric, pancreatic, biliary, and upper intestinal secretions. This volume is typically reduced to 1,500 mL by the distal ileum and is further reduced in the colon to a stool output of <250 mL/day in adults 9. During diarrheal disease, the volume of intestinal fluid output is substantially increased, overwhelming the reabsorptive capacity of the gastrointestinal tract.

In the human body, water is absorbed and secreted passively; it follows the movement of salts, based on a principle called osmosis. So, in many cases, diarrhea is caused by intestine cells secreting salts (primarily sodium) and water following passively along. Simply drinking water is ineffective for 2 reasons: (1) the large intestine is usually secreting instead of absorbing water, and (2) electrolyte losses also need compensating. As such, the standard treatment is to restore fluids intravenously with water and salts. This requires trained personnel and materials which are not sufficiently available in the Third World.

However, it was discovered that the body can absorb a simple solution containing both sugar and salt. The dry ingredients can be mixed and packaged, and then the solution can be prepared and delivered by people with minimal training. One diarrhea mechanism (like in cholera, which is a very dangerous form of profuse diarrhea), is an enterotoxin interfering with enterocyte cAMP and G-proteins 10. Rotavirus damages the villous brush border, causing osmotic diarrhea, and also produces an enterotoxin that causes a Ca++-mediated secretory diarrhea 11. However, water can still be absorbed by cAMP-independent mechanisms, like the SGLT-transporter (sodium and glucose transporter, of which two types exist). This is achieved by combining salts and glucose.

Oral rehydration therapy can be accomplished by drinking frequent small amounts of an oral rehydration salt solution.

It is important to rehydrate with solutions that contain electrolytes, especially sodium and potassium, so that electrolyte disturbances may be avoided. Sugar is absolutely essential to improve adequate absorption of electrolytes and water, but the presence of sugar in oral rehydration solutions (ORS) does tend to cause diarrhea to worsen. Although oral rehydration with a sugar solution does not stop diarrhea, and the diarrhea contributes to further loss of fluids, oral rehydration solutions (ORS) helps replace these fluids. It thus keeps the body hydrated and gives the patient a greatly improved chance of surviving the diarrhea. If a broth can be prepared from simple carbohydrates and substituted for sugar in the solution, diarrhea can sometimes be reduced while oral rehydration solutions (ORS) remains effective. Often sodium bicarbonate or sodium citrate is also added to formulas in an attempt to revert metabolic acidosis.

Oral rehydration solution (ORS) is a sodium and glucose solution which is prepared by diluting 1 sachet of oral rehydration salts in 1 liter of safe water. It is important to administer the oral rehydration solution (ORS) in small amounts at regular intervals on a continuous basis. In case oral rehydration salts packets are not available, homemade solutions consisting of either half a small spoon of salt and six level small spoons of sugar dissolved in one liter of safe water, or lightly salted rice water or even plain water may be given to PREVENT or DELAY the onset of dehydration on the way to the health facility 12. However, these solutions are inadequate for TREATING dehydration caused by acute diarrhea, particularly cholera, in which the stool loss and risk of shock are often high. To avoid dehydration, increased fluids should be given as soon as possible. All oral fluids, including oral rehydration solutions (ORS), should be prepared with the best available drinking water and stored safely. Continuous provision of nutritious food is essential and breastfeeding of infants and young children should continue 12.

If you suspect gastroenteritis in yourself:

- Sip liquids, such as a sports drink or water, to prevent dehydration. Drinking fluids too quickly can worsen the nausea and vomiting, so try to take small frequent sips over a couple of hours, instead of drinking a large amount at once.

- Take note of urination. You should be urinating at regular intervals, and your urine should be light and clear. Infrequent passage of dark urine is a sign of dehydration. Dizziness and lightheadedness also are signs of dehydration. If any of these signs and symptoms occur and you can’t drink enough fluids, seek medical attention.

- Ease back into eating. Try to eat small amounts of food frequently if you experience nausea. Otherwise, gradually begin to eat bland, easy-to-digest foods, such as soda crackers, toast, gelatin, bananas, applesauce, rice and chicken. Stop eating if your nausea returns. Avoid milk and dairy products, caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, and fatty or highly seasoned foods for a few days.

- Get plenty of rest. The illness and dehydration can make you weak and tired.

- Diarrhea usually stops in three or four days. If it does not stop, consult a trained health professional.

If you suspect gastroenteritis in your child:

- Allow your child to rest.

- When your child’s vomiting stops, begin to offer small amounts of an oral rehydration solution (CeraLyte, Enfalyte, Pedialyte). Don’t use only water or only apple juice. Drinking fluids too quickly can worsen the nausea and vomiting, so try to give small frequent sips over a couple of hours, instead of drinking a large amount at once. Try using a water dropper of rehydration solution instead of a bottle or cup.

- Gradually introduce bland, easy-to-digest foods, such as toast, rice, bananas and potatoes. Avoid giving your child full-fat dairy products, such as whole milk and ice cream, and sugary foods, such as sodas and candy. These can make diarrhea worse.

- If you’re breast-feeding, let your baby nurse. If your baby is bottle-fed, offer a small amount of an oral rehydration solution or regular formula.

Things you should know about rehydrating your child:

- Wash your hands with soap and water before preparing solution.

- Prepare a oral rehydration solution (ORS), in a clean pot, by mixing – Six (6) level teaspoons of sugar and Half (1/2) level teaspoon of Salt

or 1 packet of Oral Rehydration Salts 20.5 grams mix with one litre of clean drinking or boiled water (after cooled). Stir the mixture till all the contents dissolve. - Wash your hands and the baby’s hands with soap and water before feeding solution.

- Give the sick child as much of the solution as it needs, in small amounts frequently.

- Give child alternately other fluids – such as breast milk and juices.

- Continue to give solids if child is four months or older.

- If the child still needs oral rehydration solution (ORS) after 24 hours, make a fresh solution.

- Oral rehydration solution (ORS) does not stop diarrhea. It prevents the body from drying up. The diarrhea will stop by itself.

- If child vomits, wait ten minutes and give it oral rehydration solution (ORS) again. Usually vomiting will stop.

- If diarrhea increases and /or vomiting persists, take child over to a health clinic.

Table 8. World Health Organization (WHO) Fluid Replacement or Treatment Recommendations

| No dehydration | Oral rehydration salts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Volume of ORS (Oral Rehydration Solution) | |||

| <2 years | 50–100 ml, up to 500 mL/day | |||

| 2–9 years | 100–200 ml, up to 1000 mL/day | |||

| ≥10 years | As much as wanted, up to 2000 mL/day | |||

| Some dehydration | Oral rehydration salts | |||

| Age | Weight | Volume of ORS (Oral Rehydration Solution) | ||

| <4 months | <5 kg | 200–400 mL | ||

| 4–11 months | 5–7.9 kg | 400–600 mL | ||

| 1–2 years | 8–10.9 kg | 600–800 mL | ||

| 2–4 years | 11–15.9 kg | 800–1200 mL | ||

| 5–14 years | 16–29.9 kg | 1200–2200 mL | ||

| ≥15 years | 30 kg or more | 2200–4000 mL | ||

| Severe dehydration | Intravenous Ringer’s Lactate or, if not available, normal saline and oral rehydration salts as outlined above. Do not give plain glucose or dextrose solution. | |||

| Age< 12 months | ||||

| Timeframe | Total volume | |||

| 0–30 min | 30 ml/kg* | |||

| 30 min–6 h | 70 ml/kg | |||

| 6 h–24 h | 100 ml/kg | |||

| Age≥ 1 year | ||||

| Timeframe | Total volume | |||

| 0–30 min | 30 ml/kg* | |||

| 30 min–3 h | 70 ml/kg | |||

| 3 h–24 h | 100 ml/kg | |||

*Repeat once if radial pulse is still very weak or not detectable

[Source 13]Seek medical attention if:

- Vomiting persists more than two days

- Diarrhea persists more than several days

- Diarrhea turns bloody

- Fever is more than 102 °F (39 °C) or higher

- Lightheadedness or fainting occurs with standing

- Confusion develops

- Worrisome abdominal pain develops

Seek medical attention if your child:

- Becomes unusually drowsy.

- Vomits frequently or vomits blood.

- Has bloody diarrhea.

- Shows signs of dehydration, such as dry mouth and skin, marked thirst, sunken eyes, or crying without tears. In an infant, be alert to the soft spot on the top of the head becoming sunken and to diapers that remain dry for more than three hours.

- Is an infant and has a fever.

- Is older than three months of age and has a fever of 102 °F (39 °C) or more.

What is oral rehydration salts?

Oral rehydration salts is a special combination of dry salts that is mixed with safe water. It can help replace the fluids lost due to diarrhea.

Where can oral rehydration salts be obtained?

In most countries, oral rehydration salts packets are available from health centers, pharmacies, markets and shops.

How is the oral rehydration salts drink prepared?

- Put the contents of the oral rehydration salts packet in a clean container. Check the packet for directions and add the correct amount of clean water. Too little water could make the diarrhea worse.

- Add water only. Do not add oral rehydration salts to milk, soup, fruit juice or soft drinks. Do not add sugar.

- Stir well, and feed it to the child from a clean cup. Do not use a bottle.

What if oral rehydration salts is not available?

Give the child a drink made with 6 level teaspoons of sugar and 1/2 level teaspoon of salt dissolved in 1 liter of clean water.

Be very careful to mix the correct amounts. Too much sugar can make the diarrhea worse. Too much salt can be extremely harmful to the child.

Making the mixture a little too diluted (with more than 1 liter of clean water) is not harmful.

When should oral rehydration solution be used?

When a child has three or more loose stools in a day, begin to give oral rehydration solution (ORS). In addition, for 10–14 days, give children over 6 months of age 20 milligrams of zinc per day (tablet or syrup); give children under 6 months of age 10 milligrams per day (tablet or syrup).

How much oral rehydration solution do I feed?

Encourage the child to drink as much as possible and feed after every loose motion. Adults and large children should drink at least 3 quarts or liters of Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS) a day until they are well.

Each Feeding:

- For a child under the age of two: A child under the age of 2 years needs at least 1/4 to 1/2 of a large (250-milliliter) cup of the oral rehydration solution (ORS) drink after each watery stool.

- For older children: A child aged 2 years or older needs at least 1/2 to 1 whole large (250-milliliter) cup of the oral rehydration solution (ORS) drink after each watery stool.

For Severe Dehydration:

Drink sips of the Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS) (or give the ORS solution to the conscious dehydrated person) every 5 minutes until urination becomes normal. It’s normal to urinate four or five times a day.

How do I feed the solution?

- Give it slowly, preferably with a teaspoon.

- If the child vomits it, give it again.

The drink should be given from a cup (feeding bottles are difficult to clean properly). Remember to feed sips of the liquid slowly.

What if the child vomits?

If the child vomits, wait for ten minutes and then begin again. Continue to try to feed the drink to the child slowly, small sips at a time. The body will retain some of the fluids and salts needed even though there is vomiting.

For how long do I feed the liquids?

Extra liquids should be given until the diarrhea has stopped. This will usually take between three and five days.

How do I store the oral rehydration solution?

Store the liquid in a cool place. Chilling the Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS) may help. If the child still needs ORS after 24 hours, make a fresh solution.

How to make Oral Rehydration Solutions

Home made Oral Rehydration Solutions Recipe

Preparing 1 (one) Liter solution using Salt, Sugar and Water at Home.

Mix an oral rehydration solution using the following recipe. Ingredients:

- Six (6) level teaspoons of Sugar (molasses and other forms of raw sugar can be used instead of white sugar, and these contain more potassium than white sugar)

- Half (1/2) level teaspoon of Salt

- One Liter of clean drinking or boiled water and then cooled – 5 cupfuls (each cup about 200 ml.)

Preparation Method:

- Stir the mixture till the salt and sugar dissolve.

- If possible, add 1/2 cup orange juice or some mashed banana to improve the taste and provide some potassium.

NOTE: Do not use too much salt. If the solution has too much salt the child may refuse to drink it. Also, too much salt can, in extreme cases, cause convulsions. Too little salt does no harm but is less effective in preventing dehydration. A rough guide to the amount of salt is that the solution should taste no saltier than tears.

A good substitute for oral rehydration solutions (ORS)

- Ingredients:

- 1/2 to 1 cup precooked baby rice cereal or 1½ tablespoons of granulated sugar

- 2 cups of water

- 1/2 tsp. salt

- Instructions:

- Mix well the rice cereal (or sugar), water, and salt together until the mixture thickens but is not too thick to drink. Give the mixture often by spoon and offer the child as much as he or she will accept (every minute if the child will take it). Continue giving the mixture with the goal of replacing the fluid lost: one cup lost, give a cup. Even if the child is vomiting, the mixture can be offered in small amounts (1-2 tsp.) every few minutes or so.

- Banana or other non-sweetened mashed fruit can help provide potassium.

- Continue feeding children when they are sick and to continue breastfeeding if the child is being breastfed.

- Mix well the rice cereal (or sugar), water, and salt together until the mixture thickens but is not too thick to drink. Give the mixture often by spoon and offer the child as much as he or she will accept (every minute if the child will take it). Continue giving the mixture with the goal of replacing the fluid lost: one cup lost, give a cup. Even if the child is vomiting, the mixture can be offered in small amounts (1-2 tsp.) every few minutes or so.

The following traditional remedies also make highly effective oral rehydration solutions (ORS) and are suitable drinks to prevent a child from losing too much liquid during diarrhea:

- Breastmilk

- Gruels (diluted mixtures of cooked cereals and water)

- Carrot Soup

- Rice water – Congee

If none of these drinks is available, other alternatives are:

- Fresh fruit juice

- Weak tea

- Green coconut water

If nothing else is available, give:

- water from the cleanest possible source (if possible brought to the boil and then cooled).

Food poisoning fluid replacement

Food poisoning, also called foodborne illness, is caused by bacteria, viruses, parasites or their toxins in the food you eat are the most common causes of food poisoning. Some of these toxins are found naturally in foods, while some have accumulated in the environment.

Infectious organisms or their toxins can contaminate food at any point of processing or production. Contamination can also occur at home if food is incorrectly handled or cooked.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that each year 48 million people get sick from a foodborne illness, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die. CDC estimates that 1 in 6 Americans get sick from eating contaminated food every year 14.

If you have food poisoning you’ll probably have gastroenteritis symptoms such as nausea, abdominal cramps, diarrhea or vomiting or flu-like symptoms, which can start within hours of eating contaminated food. Most people have only mild illnesses, lasting a few hours to several days. However, some develop severe illness requiring hospitalization, and some illnesses result in long-term health problems and occasionally people die from food poisoning. Infections transmitted by food can result in chronic arthritis, brain and nerve damage and hemolytic uremic syndrome, which causes kidney failure. But most often, food poisoning is mild and resolves without treatment.

Some wild mushrooms, including the death cap, are extremely poisonous. You should not eat wild-harvested mushrooms unless they have been definitely identified as safe. Seek immediate medical treatment If you think you may have eaten poisonous mushrooms.

Large fish, such as shark, swordfish and marlin, may accumulate relatively high levels of mercury. You should limit your consumption of these fish, especially if you are a child, are pregnant or planning pregnancy.

- Food poisoning is especially serious and potentially life-threatening for young children, pregnant women and their fetuses, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems.

- If you’re pregnant, elderly or very young, or your immune system is weak through illness or drugs, you’re at greater risk of food poisoning and possibly serious complications.

- If you’re pregnant, Listeria can cause you to miscarry, even if you don’t know you’ve been infected. If you notice symptoms – usually like a mild flu but also diarrhea, vomiting and nausea – contact your doctor immediately.

- If you experience any of the following signs or symptoms, seek medical attention immediately:

- Frequent episodes of vomiting and inability to keep liquids down

- Bloody vomit or stools

- Diarrhea for more than three days

- Extreme pain or severe abdominal cramping

- An oral temperature higher than 100.4° F (38° C)

- Signs or symptoms of dehydration — excessive thirst, dry mouth, little or no urination, severe weakness, dizziness, or lightheadedness

- Neurological symptoms such as blurry vision, muscle weakness and tingling in the arms.

Prevent Dehydration

Drink plenty of liquids to replace fluids that are lost from throwing up and diarrhea.

If diarrhea is severe, oral rehydration solution such as Ceralyte, Pedialyte or Oralyte, should be drunk to replace the fluid losses and prevent dehydration. Sports drinks such as Gatorade do not replace the losses correctly and should not be used for the treatment of diarrheal illness. Sports drinks may not replace important nutrients and minerals. Oral rehydration fluids that you can get over the counter are most helpful for mild dehydration.

If you think you or someone you are caring for is severely dehydrated, see a doctor.

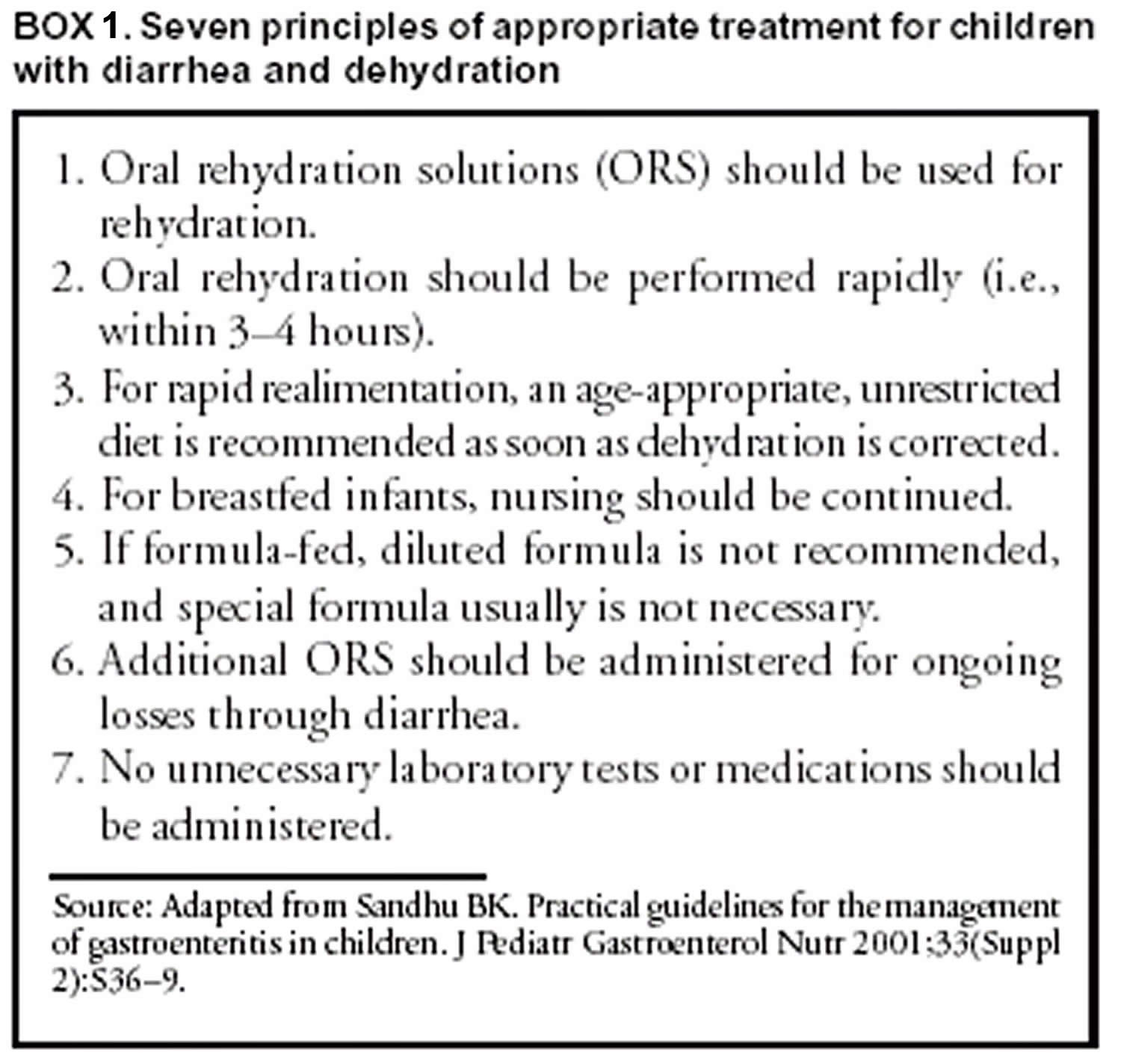

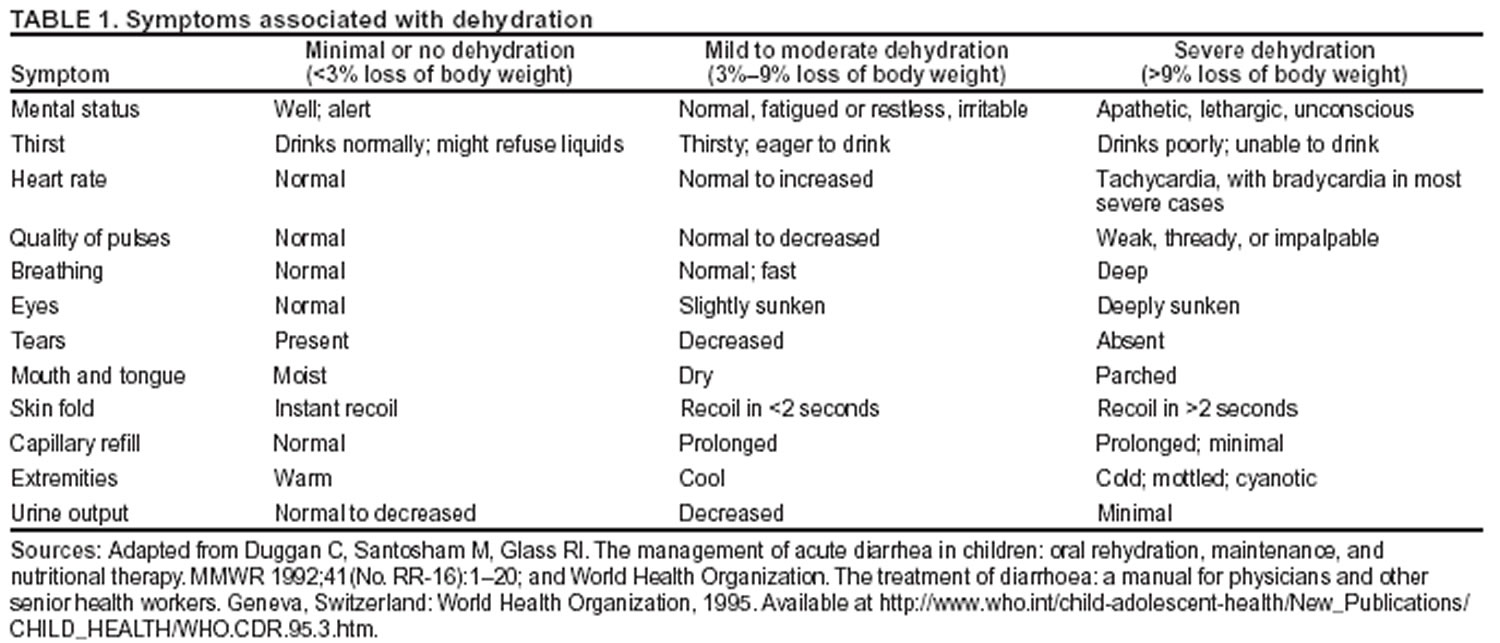

Seven basic principles guide optimal treatment of acute gastroenteritis (Box 1) 15; more specific recommendations for treating different degrees of dehydration have been recommended by the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Table 1) 16. Treatment should include two phases: rehydration and maintenance. In the rehydration phase, the fluid deficit is replaced quickly (i.e., during 3–4 hours) and clinical hydration is attained. In the maintenance phase, maintenance calories and fluids are administered. Rapid realimentation should follow rapid rehydration, with a goal of quickly returning the patient to an age-appropriate unrestricted diet, including solids. Gut rest is not indicated. Breastfeeding should be continued at all times, even during the initial rehydration phases. The diet should be increased as soon as tolerated to compensate for lost caloric intake during the acute illness. Lactose restriction is usually not necessary (although it might be helpful in cases of diarrhea among malnourished children or among children with a severe enteropathy), and changes in formula usually are unnecessary. Full-strength formula usually is tolerated and allows for a more rapid return to full energy intake. During both phases, fluid losses from vomiting and diarrhea are replaced in an ongoing manner. Antidiarrheal medications are not recommended for infants and children, and laboratory studies should be limited to those needed to guide clinical management.

Minimal dehydration

For patients with minimal or no dehydration, treatment is aimed at providing adequate fluids and continuing an age-appropriate diet. Patients with diarrhea must have increased fluid intake to compensate for losses and cover maintenance needs; use of oral rehydration solutions (ORS) should be encouraged. In principle, 1 mL of fluid should be administered for each gram of output. In hospital settings, soiled diapers can be weighed (without urine), and the estimated dry weight of the diaper can be subtracted. When losses are not easily measured, 10 mL of additional fluid can be administered per kilogram body weight for each watery stool or 2 mL/kg body weight for each episode of emesis. As an alternative, children weighing <10 kg should be administered 60–120 mL (2–4 ounces) oral rehydration solution (ORS) for each episode of vomiting or diarrheal stool, and those weighing >10 kg should be administered 120–240 mL (4–8 ounces). Nutrition should not be restricted (see Dietary Therapy).

Mild to Moderate Dehydration

Children with mild to moderate dehydration should have their estimated fluid deficit rapidly replaced. These updated recommendations include administering 50–100 mL of oral rehydration solution (ORS)/kg body weight during 2–4 hours to replace the estimated fluid deficit, with additional ORS administered to replace ongoing losses. Using a teaspoon, syringe, or medicine dropper, limited volumes of fluid (e.g., 5 mL or 1 teaspoon) should be offered at first, with the amount gradually increased as tolerated. If a child appears to want more than the estimated amount of ORS, more can be offered. Although administering ORS rapidly is safe, vomiting might be increased with larger amounts. Nasogastric (NG) feeding allows continuous administration of ORS at a slow, steady rate for patients with persistent vomiting or oral ulcers. Clinical trials support using nasogastric feedings, even for vomiting patients 17. Rehydration through an NG tube can be particularly useful in emergency department settings, where rapid correction of hydration might prevent hospitalization. Although rapid IV hydration can also prevent hospital admission, rapid nasogastric rehydration can be well-tolerated, more cost-effective, and associated with fewer complications 17. In addition, a randomized trial of ORS versus IV rehydration for dehydrated children demonstrated shorter stays in emergency departments and improved parental satisfaction with oral rehydration 18.

Certain children with mild to moderate dehydration will not improve with ORT; therefore, they should be observed until signs of dehydration subside. Similarly, children who do not demonstrate clinical signs of dehydration but who demonstrate unusually high output should be held for observation. Hydration status should be reassessed on a regular basis, and might be performed in an emergency department, office, or other outpatient setting. After dehydration is corrected, further management can be implemented at home, provided that the child’s caregivers demonstrate comprehension of home rehydration techniques (including continued feeding), understand indications for returning for further evaluation, and have the means to do so. Even among children whose illness appears uncomplicated on initial assessment, a limited percentage might not respond adequately to ORT; therefore, a plan for reassessment should be agreed upon. Caregivers should be encouraged to return for medical attention if they have any concerns, if they are not sure that rehydration is proceeding well, or if new or worsening symptoms develop.

Severe dehydration

Severe dehydration constitutes a medical emergency requiring immediate IV rehydration. Lactated Ringer’s solution, normal saline, or a similar solution should be administered (20 mL/kg body weight) until pulse, perfusion, and mental status return to normal. This might require two IV lines or even alternative access sites (e.g., intraosseous infusion). The patient should be observed closely during this period, and vital signs should be monitored on a regular basis. Serum electrolytes, bicarbonate, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and serum glucose levels should be obtained, although commencing rehydration therapy without these results is safe. Normal saline or Lactated Ringer’s infusion is the appropriate first step in the treatment of hyponatremic and hypernatremic dehydration. Hypotonic solutions should not be used for acute parenteral rehydration 19.

Severely dehydrated patients might require multiple administrations of fluid in short succession. Overly rapid rehydration is unlikely to occur as long as weight-based amounts are administered with close observation. Errors occur most commonly in settings where adult dosing is administered to infants (e.g., “500 mL normal saline IV bolus x 2” would provide 200 mL/kg body weight for an average infant aged 2–3 months). Edema of the eyelids and extremities can indicate overhydration. Diuretics should not be administered. After the edema has subsided, the patient should be reassessed for continued therapy. With frail or malnourished infants, smaller amounts (10 mL/kg body weight) are recommended because of the reduced ability of these infants to increase cardiac output and because distinguishing dehydration from sepsis might be difficult among these patients. Smaller amounts also will facilitate closer evaluation. Hydration status should be reassessed frequently to determine the adequacy of replacement therapy. A lack of response to fluid administration should raise the suspicion of alternative or concurrent diagnoses, including septic shock and metabolic, cardiac, or neurologic disorders.

As soon as the severely dehydrated patient’s level of consciousness returns to normal, therapy usually can be changed to the oral route, with the patient taking by mouth the remaining estimated deficit. An nasogastric tube can be helpful for patients with normal mental status but who are too weak to drink adequately. Although no studies have specifically documented increased aspiration risk with nasogastric tube use in obtunded patients, IV therapy is typically favored for such patients. Although leaving IV access in place for these patients is reasonable in case it is needed again, early reintroduction of ORS is safer. Using IV catheters is associated with frequent minor complications, including extravasation of IV fluid, and with rare substantial complications, including the inadvertent administration of inappropriate fluid (e.g., solutions containing excessive potassium). In addition, early oral rehydration solution (ORS) will probably encourage earlier resumption of feeding, and data indicate that resolution of acidosis might be more rapid with ORS than with IV fluid 17.

Dietary therapy

Recommendations for maintenance dietary therapy depend on the age and diet history of the patient. Breastfed infants should continue nursing on demand. Formula-fed infants should continue their usual formula immediately upon rehydration in amounts sufficient to satisfy energy and nutrient requirements. Lactose-free or lactose-reduced formulas usually are unnecessary. A meta-analysis of clinical trials indicates no advantage of lactose-free formulas over lactose-containing formulas for the majority of infants, although certain infants with malnutrition or severe dehydration recover more quickly when given lactose-free formula 20. Patients with true lactose intolerance will have exacerbation of diarrhea when a lactose-containing formula is introduced. The presence of low pH (<6.0) or reducing substances (>0.5%) in the stool is not diagnostic of lactose intolerance in the absence of clinical symptoms. Although medical practice has often favored beginning feedings with diluted (e.g., half- or quarter-strength) formula, controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that this practice is unnecessary and is associated with prolonged symptoms 21 and delayed nutritional recovery 22.

Formulas containing soy fiber have been marketed to physicians and consumers in the United States, and added soy fiber has been reported to reduce liquid stools without changing overall stool output 23. This cosmetic effect might have certain benefits with regard to diminishing diaper rash and encouraging early resumption of normal diet but is probably not sufficient to merit its use as a standard of care. A reduction in the duration of antibiotic-associated diarrhea has been demonstrated among older infants and toddlers fed formula with added soy fiber 24.

Children receiving semisolid or solid foods should continue to receive their usual diet during episodes of diarrhea. Foods high in simple sugars should be avoided because the osmotic load might worsen diarrhea; therefore, substantial amounts of carbonated soft drinks, juice, gelatin desserts, and other highly sugared liquids should be avoided. Certain guidelines have recommended avoiding fatty foods, but maintaining adequate calories without fat is difficult, and fat might have a beneficial effect of reducing intestinal motility. The practice of withholding food for >24 hours is inappropriate. Early feeding decreases changes in intestinal permeability caused by infection 25, reduces illness duration, and improves nutritional outcomes 26. Highly specific diets (e.g., the BRAT [bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast] diet) have been commonly recommended. Although certain benefits might exist from green bananas and pectin in persistent diarrhea 27, the BRAT [bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast] diet is unnecessarily restrictive and, similar to juice-centered diets, can provide suboptimal nutrition for the patient’s nourishment and recovering gut. Severe malnutrition can occur after gastroenteritis if prolonged gut rest or clear fluids are prescribed 28.

Children in underdeveloped countries often have multiple episodes of diarrhea in a single season, making diarrhea a contributing factor to suboptimal nutrition, which can increase the frequency and severity of subsequent episodes 29. For this reason, increased nutrient intake should be administered after an episode of diarrhea. Recommended foods include age-appropriate unrestricted diets, including complex carbohydrates, meats, yogurt, fruits, and vegetables. Children should as best as possible maintain caloric intake during acute episodes, and subsequently should receive additional nutrition to compensate for any shortfalls arising during the illness.

Supplemental Zinc therapy