Frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia also known as frontotemporal lobe dementia, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), FTD, frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism or Pick’s disease, is an umbrella term for a group of brain disorders that primarily affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain 1. The frontal and temporal lobes of the brain are generally associated with personality, behavior and language. The frontal lobe is the largest lobe in the brain and is located right behind the forehead. The frontal lobe is critical for thinking, planning, decision making and other higher mental processes. The frontal lobe helps people to manage and control emotional responses. The temporal lobes are located below and to both sides of the frontal lobe. The temporal lobes are believed to be involved in semantic memory, or your knowledge of objects, people, words and faces. The temporal lobes also play a role in language and emotion. In frontotemporal dementia, the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain shrink (atrophy). Signs and symptoms vary, depending on which part of the brain is affected. Some people with frontotemporal dementia have dramatic changes in their personalities and become socially inappropriate, impulsive or emotionally indifferent, while others lose the ability to use language properly. Presently, the term frontotemporal dementia encompasses clinical disorders that include changes in behavior, language, executive function and often motor symptoms 2. Frontotemporal dementia usually causes changes in behavior or language problems at first. These come on gradually and get worse slowly over time. Eventually, most people will experience problems in both of these areas. Some people also develop physical problems and difficulties with their mental abilities. Frontotemporal dementia can be misdiagnosed as a psychiatric problem or as Alzheimer’s disease.

Frontotemporal dementia is the third most common form of dementia across all age groups, after Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia and is the second most common cause of early-onset dementia (age <65) and usually involves patients with age ranges from 45 to 65 3, 4. Frontotemporal dementia can occur in people as young as 20. But it usually begins between ages 40 and 60. The average age at which it begins is 54. People with frontotemporal dementia have abnormal substances called tangles, Pick bodies, and Pick cells and 3R tau proteins inside nerve cells in the damaged areas of the brain.

The first description of a patient with frontotemporal dementia was made by Arnold Pick in 1892 5; the patient had aphasia (aphasia affects a person’s ability to express and understand written and spoken language), lobar atrophy, and presenile dementia. In 1911, Alois Alzheimer recognized the characteristic association with Pick bodies and named the clinicopathological entity Pick’s disease 6, which led to the use of Pick’s disease as a synonym for frontotemporal dementia. In 1982, Mesulam described a language subtype of the disorder, later defined as primary progressive aphasia 7. It was later replaced by the term frontotemporal dementia based on distinct clinical and histopathological criteria, assigned by a research group from the United Kingdom and Sweden in 1994 8.

Frontotemporal dementia is classified into two distinct clinical types; behavior variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) and language type frontotemporal dementia 4. The language type of frontotemporal dementia is further classified into non-fluent variant primary progressive aphasia (nfvPPA), and semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) depending on the areas of neuronal loss in frontal and temporal lobes 9.

Frontotemporal dementia symptoms include marked changes in social behavior and personality, and/or problems with language. People with behavior changes may have disinhibition (with socially inappropriate behavior), apathy and loss of empathy, hyperorality (eating excessive amounts of food or attempting to consume inedible things), agitation, compulsive behavior, and various other changes 10. Examples of problems with language include difficulty speaking or understanding speech. Some people with frontotemporal dementia also develop a motor syndrome such as parkinsonism or motor neuron disease (which may be associated with various additional symptoms).

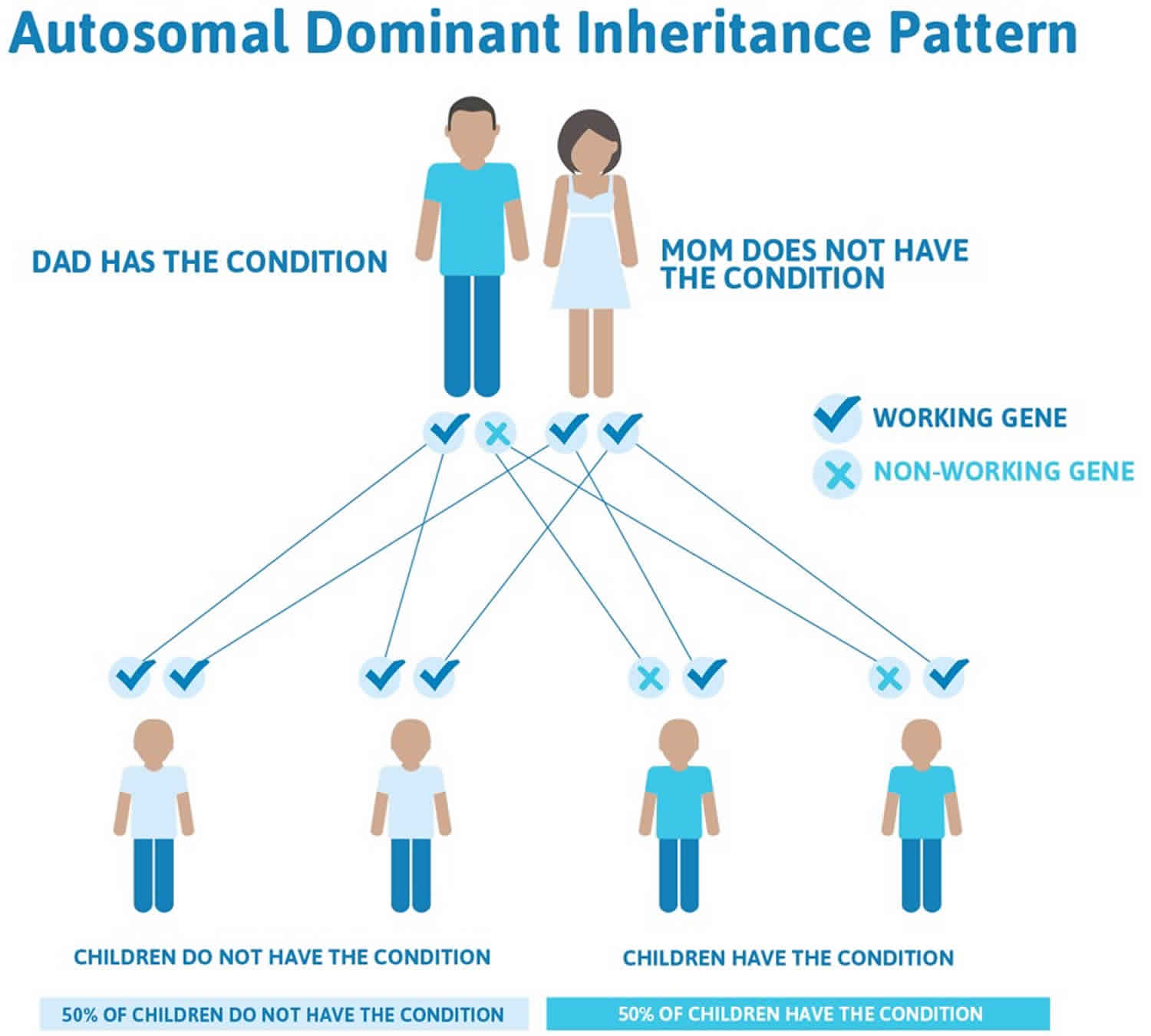

The exact cause of frontotemporal dementia is unknown, but it’s mainly a sporadic disease. Genetics also plays a key role where approximately 30-40% of cases are passed down through families 11, 12. Among them, 13.4% of cases have an autosomal dominant inheritance. Mutations in over 20 genes have been identified in the possible development of frontotemporal dementia 4. Commonly involved genes are MAPT gene (microtubules associated protein tau gene located on chromosome 17q21.32), GRN gene (granulin gene on chromosome 17q21.32) and hexanucleotide repeat expansion of the chromosome 9 open-reading-frame 72 (C9orf72) gene on chromosomal location 9p21.2 (responsible for cytoskeleton organization) 13, 14. It is also postulated that C9orf72 gene mutation is a continuum between frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease) and is responsible for the occurrence of both entities. If you have a family history of frontotemporal dementia, you may want to consider talking to your doctor about being referred to a geneticist and possibly having a genetic test to see if you’re at risk. Head trauma and thyroid disease have been linked with the development of frontotemporal dementia with a 3.3-fold higher risk and 2.5-fold higher risk, respectively 4.

Frontotemporal dementia is rare with estimation of 1.61 to 4.1 cases per one hundred thousand people annually 15. One study showed the prevalence of frontotemporal dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal syndrome was 10.8 per 100,000 with peak prevalence at the age range of 65 to 69 years 15. There is an estimated twenty to thirty thousand people in the United States with frontotemporal dementia at one time 16.

Changes in the Brain

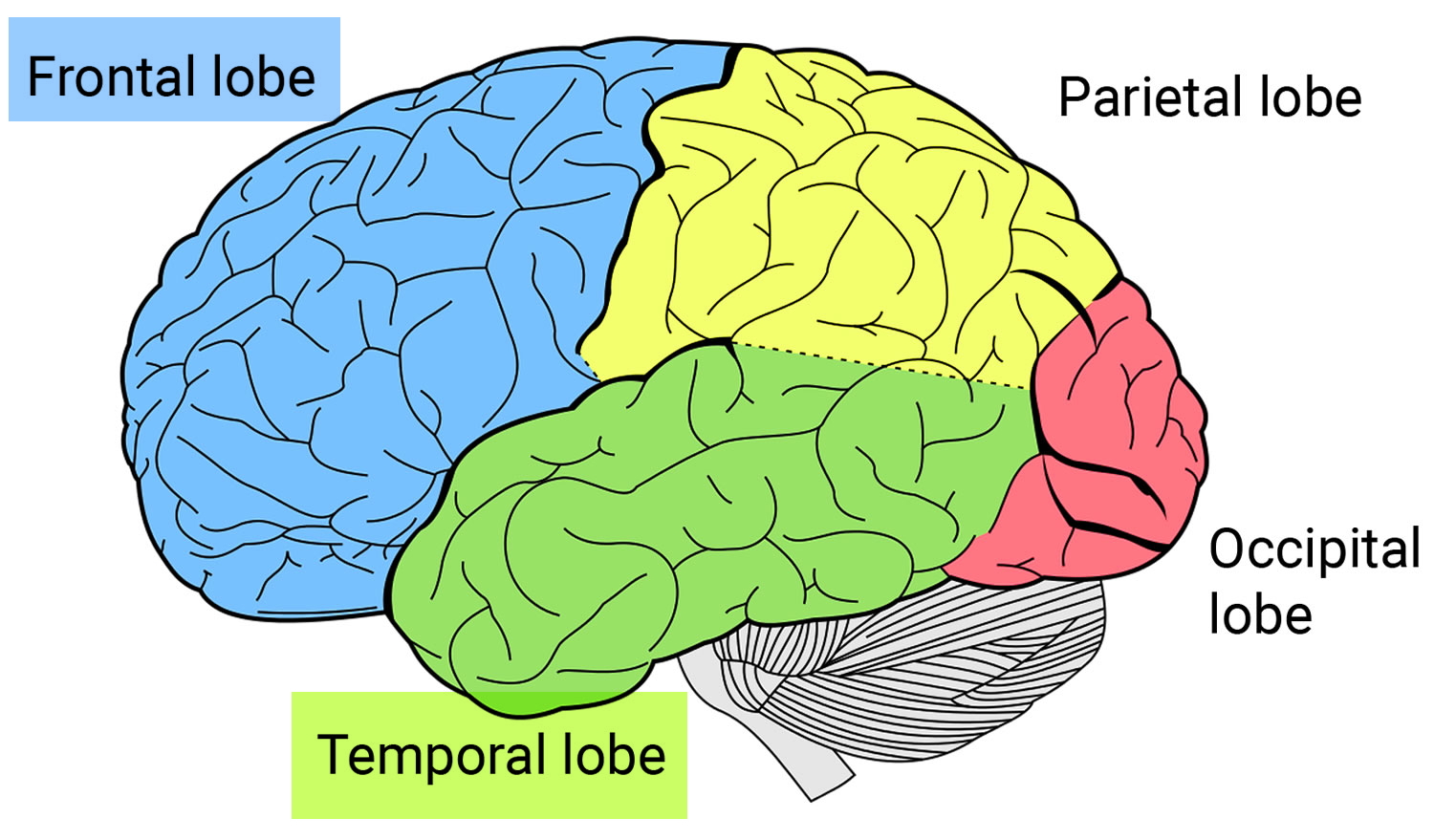

Frontotemporal disorders affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain (see Brain image below). They can begin in the frontal lobe, the temporal lobe, or both. Initially, frontotemporal disorders leave other brain regions untouched, including those that control short-term memory 17.

The frontal lobes, situated above the eyes and behind the forehead both on the right and left sides of the brain, direct executive functioning. This includes planning and sequencing (thinking through which steps come first, second, third, and so on), prioritizing (doing more important activities first and less important activities last), multitasking (shifting from one activity to another as needed), and monitoring and correcting errors.

When functioning well, the frontal lobes also help manage emotional responses. They enable people to avoid inappropriate social behaviors, such as shouting loudly in a library or at a funeral. They help people make decisions that make sense for a given situation. When the frontal lobes are damaged, people may focus on insignificant details and ignore important aspects of a situation or engage in purposeless activities. The frontal lobes are also involved in language, particularly linking words to form sentences, and in motor functions, such as moving the arms, legs, and mouth.

The temporal lobes, located below and to the side of each frontal lobe on the right and left sides of the brain, contain essential areas for memory but also play a major role in language and emotions. They help people understand words, speak, read, write, and connect words with their meanings. They allow people to recognize objects and to relate appropriate emotions to objects and events. When the temporal lobes are dysfunctional, people may have difficulty recognizing emotions and responding appropriately to them.

Which lobe—and part of the lobe—is affected first determines which symptoms appear first. For example, if the disease starts in the part of the frontal lobe responsible for decision-making, then the first symptom might be trouble managing finances. If it begins in the part of the temporal lobe that connects emotions to objects, then the first symptom might be an inability to recognize potentially dangerous objects—a person might reach for a snake or plunge a hand into boiling water, for example.

Frontotemporal degeneration vs Alzheimer’s disease

Frontotemporal degeneration

- Different symptoms. Frontotemporal dementia brings a gradual, progressive decline in behavior, language or movement, with memory usually relatively preserved.

- Frontotemporal degeneration typically strikes younger people. Although age of onset ranges from 21 to 80, the majority of frontotemporal dementia cases occur between 45 and 64. Frontotemporal degeneration occurs in a younger age group than dementia of the Alzheimer type, with peak incidence occurring in individuals aged 55-65 years 18. Therefore, frontotemporal dementia has a substantially greater impact on work, family, and the economic burden faced by families than Alzheimer’s disease.

- Frontotemporal degeneration is less common and still far less known. Frontotemporal dementia’s estimated U.S. prevalence is around 60,000 cases 19, and many in the medical community remain unfamiliar with it. Frontotemporal dementia is frequently misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s, depression, Parkinson’s disease, or a psychiatric condition. On average, it currently takes 3.6 years to get an accurate diagnosis.

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia — a continuous decline in thinking, behavioral and social skills that disrupts a person’s ability to function independently.

Memory loss is the key symptom of Alzheimer’s disease. The early signs of Alzheimer’s disease may be forgetting or difficulty remembering recent events or conversations. As Alzheimer’s disease progresses, a person with Alzheimer’s disease will develop severe memory impairment and lose the ability to carry out everyday tasks.

At first, a person with Alzheimer’s disease may be aware of having difficulty with remembering things and organizing thoughts. A family member or friend may be more likely to notice how the symptoms worsen.

10 Early Signs and Symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease:

- Memory loss that disrupts daily life: One of the most common signs of Alzheimer’s disease, especially in the early stage, is forgetting recently learned information. Others include forgetting important dates or events, asking for the same information over and over, and increasingly needing to rely on memory aids (e.g., reminder notes or electronic devices) or family members for things they used to handle on their own.

- Challenges in planning or solving problems: Some people may experience changes in their ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers. They may have trouble following a familiar recipe or keeping track of monthly bills. They may have difficulty concentrating and take much longer to do things than they did before.

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks at home, at work or at leisure: People with Alzheimer’s often find it hard to complete daily tasks. Sometimes, people may have trouble driving to a familiar location, managing a budget at work or remembering the rules of a favorite game.

- Confusion with time or place: People with Alzheimer’s can lose track of dates, seasons and the passage of time. They may have trouble understanding something if it is not happening immediately. Sometimes they may forget where they are or how they got there.

- Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships: For some people, having vision problems is a sign of Alzheimer’s. They may have difficulty reading, judging distance and determining color or contrast, which may cause problems with driving.

- New problems with words in speaking or writing: People with Alzheimer’s may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have problems finding the right word or call things by the wrong name (e.g., calling a “watch” a “hand-clock”).

- Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps: A person with Alzheimer’s disease may put things in unusual places. They may lose things and be unable to go back over their steps to find them again. Sometimes, they may accuse others of stealing. This may occur more frequently over time.

- Decreased or poor judgment: People with Alzheimer’s may experience changes in judgment or decision-making. For example, they may use poor judgment when dealing with money, giving large amounts to telemarketers. They may pay less attention to grooming or keeping themselves clean.

- Withdrawal from work or social activities: A person with Alzheimer’s may start to remove themselves from hobbies, social activities, work projects or sports. They may have trouble keeping up with a favorite sports team or remembering how to complete a favorite hobby. They also may avoid being social because of the changes they have experienced.

- Changes in mood and personality: The mood and personalities of people with Alzheimer’s can change. They can become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, at work, with friends or in places where they are out of their comfort zone.

Memory

Everyone has occasional memory lapses. It’s normal to lose track of where you put your keys or forget the name of an acquaintance. But the memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s disease persists and worsens, affecting the ability to function at work or at home.

People with Alzheimer’s may:

- Repeat statements and questions over and over

- Forget conversations, appointments or events, and not remember them later

- Routinely misplace possessions, often putting them in illogical locations

- Get lost in familiar places

- Eventually forget the names of family members and everyday objects

- Have trouble finding the right words to identify objects, express thoughts or take part in conversations

Thinking and reasoning

Alzheimer’s disease causes difficulty concentrating and thinking, especially about abstract concepts such as numbers.

Multitasking is especially difficult, and it may be challenging to manage finances, balance checkbooks and pay bills on time. These difficulties may progress to an inability to recognize and deal with numbers.

Making judgments and decisions

The ability to make reasonable decisions and judgments in everyday situations will decline. For example, a person may make poor or uncharacteristic choices in social interactions or wear clothes that are inappropriate for the weather. It may be more difficult to respond effectively to everyday problems, such as food burning on the stove or unexpected driving situations.

Planning and performing familiar tasks

Once-routine activities that require sequential steps, such as planning and cooking a meal or playing a favorite game, become a struggle as the disease progresses. Eventually, people with advanced Alzheimer’s may forget how to perform basic tasks such as dressing and bathing.

Changes in personality and behavior

Brain changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease can affect moods and behaviors. Problems may include the following:

- Depression

- Apathy

- Social withdrawal

- Mood swings

- Distrust in others

- Irritability and aggressiveness

- Changes in sleeping habits

- Wandering

- Loss of inhibitions

- Delusions, such as believing something has been stolen

Preserved skills

Many important skills are preserved for longer periods even while symptoms worsen. Preserved skills may include reading or listening to books, telling stories and reminiscing, singing, listening to music, dancing, drawing, or doing crafts.

These skills may be preserved longer because they are controlled by parts of the brain affected later in the course of the disease.

Current Alzheimer’s disease medications may temporarily improve symptoms or slow the rate of decline. These treatments can sometimes help people with Alzheimer’s disease maximize function and maintain independence for a time.

Types of frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal degeneration is the umbrella term for a range of disorders that impact the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Each disorder can be identified according to the symptoms that appear first and most prominently, whether in behavior (behavioral variant frontotemporal degeneration [bvFTD]), changes in the ability to speak and understand language (primary progressive aphasia [PPA]) or in movement (corticobasal syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy). The clinical syndrome where FTD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) occur in the same person is referred to as ALS-Frontotemporal Spectrum Disorder (ALS-FTSD).

The most common types of FTD are:

- Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). Progressive behavior/personality decline—characterized by changes in personality, behavior, emotions, and judgment (called

behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia). - Primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Progressive language decline — Aphasia means difficulty communicating. This form has three subtypes:

- Progressive Nonfluent/Agrammatic variant PPA (nfvPPA) also called progressive nonfluent aphasia, which affects the ability to speak.

- Semantic variant PPA also called semantic dementia, which affects the ability to use and understand language.

- Logopenic variant PPA also known as PPA-L have difficulty finding words when they are speaking.

- Frontotemporal Dementia with Motor Neuron Disease (FTD-MND) also called Frontotemporal Degeneration with ALS (FTD-ALS).

- Frontotemporal degeneration and the motor neuron disease ALS can occur in the same individual. ALS also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease in the US, is sometimes used interchangeably with the term motor neuron disease (MND). Motor neuron disease is also used as a general term for a group of progressive neurological disorders in which there is a loss of nerve cells called motor neurons. These cells control voluntary muscle activity such as speaking, walking, and talking. Individuals may exhibit weakness, muscle loss (atrophy), tiny involuntary muscle twitches (fasciculation), difficulty speaking (dysarthria) and difficult swallowing (dysphagia). Involuntary control of muscle activity such as breathing and increased tightness and stiffness of muscles (spasticity) is also affected. When people have symptoms of frontotemporal degeneration and motor neuron disease, they may be described as having FTD associated with motor neuron disease (FTD-MND), or FTD associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (FTD-ALS).

- Corticobasal Syndrome (CBS)

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP)

In the early stages it can be hard to know which of these disorders a person has because symptoms and the order in which they appear can vary widely from one person to the next. Also, the same symptoms can appear later in different disorders. For example, language problems are most typical of primary progressive aphasia but can also appear later in the course of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD)

Of the clinical syndromes, frontotemporal dementia with motor neuron disease (FTD-MND) is the most heritable and svPPA is the least heritable (Goldman et al., 2005).

Table 1. Types of Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) or Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (FLTD)

[Source: The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration 20 ]Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD)

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) frequently referred to as frontotemporal dementia or Pick’s disease, is the most common form of FTD, is responsible for about half of all cases of frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) 21. Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) presents with early changes in behavior, personality, emotion and executive control 22. These changes can include new behavioral symptoms such as disinhibition, new compulsions, dietary changes or symptoms like apathy and lack of empathy. The hallmarks of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) are personality changes, apathy, and a progressive decline in socially appropriate behavior, judgment, self-control, and empathy. Unlike in Alzheimer’s disease, memory is usually relatively spared in bvFTD. People with bvFTD typically do not recognize the changes in their own behavior, or exhibit awareness or concern for the effect their behavior has on the people around them.

Many of these initial symptoms are easily mistaken for a psychiatric illness making bvFTD patients at high risk for misdiagnosis 23. In order to meet clinical criteria for a diagnosis of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), there needs to be a constellation of at least three symptoms fitting into the six categories which include: disinhibition, apathy, lack of empathy, compulsions, hyperorality and executive dysfunction 22.

The behavioral symptoms of bvFTD correlate with dysfunction in the paralimbic areas including medial frontal, orbital frontal, anterior cingulate and frontoinsular cortices 24. Right hemisphere atrophy is associated more with behavior changes 25. Von Economo neurons, present primarily in large brained, socially complex animals 26 are found in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, frontoinsular and orbital frontal cortex 27. Seeley has shown that Von Economo neurons are selectively vulnerable in bvFTD but not Alzheimer’s disease 27. These Von Economo neuron-containing areas within the salience network are selectively vulnerable and represent the epicenter of bvFTD pathology, before there is spread to other areas within the network 28. Neurodegeneration is thought to spread within the network with toxic protein aggregates moving from cell to cell in a prion-like manner 29.

It is imperative to take an excellent and thorough clinical history with the goal of identifying the brain region where the disease begins. New symptoms developing through time can localize the spread of neuropathologic changes with disease progression. There are heterogeneous clinical phenotypes with bvFTD based upon the regional spread in the individual patient. Executive control is lost once the neuropathology involves the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex that interacts with bilateral parietal lobes 28.

Diagnostic criteria for behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD)

In 2011, an international consortium developed revised guidelines for the diagnosis of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) based on recent literature and collective experience 22. The following criteria delineates the new criteria for bvFTD (Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Degeneration or Frontotemporal Dementia).

- I. Neurodegenerative disease

- The following symptom must be present to meet criteria for bvFTD

- A. Shows progressive deterioration of behaviour and/or cognition by observation or history (as provided by a knowledgeable informant).

- The following symptom must be present to meet criteria for bvFTD

- II. Possible bvFTD

- Three of the following behavioral/cognitive symptoms (A–F) must be present to meet criteria. Ascertainment requires that symptoms be persistent or recurrent, rather than single or rare events.

- A. Early* behavioral disinhibition [one of the following symptoms (A.1–A.3) must be present]:

- A.1. Socially inappropriate behaviour

- A.2. Loss of manners or decorum

- A.3. Impulsive, rash or careless actions

- B. Early apathy or inertia [one of the following symptoms (B.1–B.2) must be present]:

- B.1. Apathy

- B.2. Inertia

- C. Early loss of sympathy or empathy [one of the following symptoms (C.1–C.2) must be present]:

- C.1. Diminished response to other people’s needs and feelings

- C.2. Diminished social interest, interrelatedness or personal warmth

- D. Early perseverative, stereotyped or compulsive/ritualistic behavior [one of the following symptoms (D.1–D.3) must be present]:

- D.1. Simple repetitive movements

- D.2. Complex, compulsive or ritualistic behaviours

- D.3. Stereotypy of speech

- E. Hyperorality and dietary changes [one of the following symptoms (E.1–E.3) must be present]:

- E.1. Altered food preferences

- E.2. Binge eating, increased consumption of alcohol or cigarettes

- E.3. Oral exploration or consumption of inedible objects

- F. Neuropsychological profile: executive/generation deficits with relative sparing of memory and visuospatial functions [all of the following symptoms (F.1–F.3) must be present]:

- F.1. Deficits in executive tasks

- F.2. Relative sparing of episodic memory

- F.3. Relative sparing of visuospatial skills

- A. Early* behavioral disinhibition [one of the following symptoms (A.1–A.3) must be present]:

- Three of the following behavioral/cognitive symptoms (A–F) must be present to meet criteria. Ascertainment requires that symptoms be persistent or recurrent, rather than single or rare events.

- III. Probable bvFTD

- All of the following symptoms (A–C) must be present to meet criteria.

- A. Meets criteria for possible bvFTD

- B. Exhibits significant functional decline (by caregiver report or as evidenced by Clinical Dementia Rating Scale or Functional Activities Questionnaire scores)

- C. Imaging results consistent with bvFTD [one of the following (C.1–C.2) must be present]:

- C.1. Frontal and/or anterior temporal atrophy on MRI or CT

- C.2. Frontal and/or anterior temporal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on PET or SPECT

- All of the following symptoms (A–C) must be present to meet criteria.

- IV. Behavioral variant FTD with definite FTLD Pathology

- Criterion A and either criterion B or C must be present to meet criteria.

- A. Meets criteria for possible or probable bvFTD

- B. Histopathological evidence of FTLD on biopsy or at post-mortem

- C. Presence of a known pathogenic mutation

- Criterion A and either criterion B or C must be present to meet criteria.

- V. Exclusionary criteria for bvFTD

- Criteria A and B must be answered negatively for any bvFTD diagnosis. Criterion C can be positive for possible bvFTD but must be negative for probable bvFTD.

- A. Pattern of deficits is better accounted for by other non-degenerative nervous system or medical disorders

- B. Behavioural disturbance is better accounted for by a psychiatric diagnosis

- C. Biomarkers strongly indicative of Alzheimer’s disease or other neurodegenerative process.

- Criteria A and B must be answered negatively for any bvFTD diagnosis. Criterion C can be positive for possible bvFTD but must be negative for probable bvFTD.

Footnote: *As a general guideline ‘early’ refers to symptom presentation within the first 3 years.

[Source 22 ]Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) symptoms

The following are possible symptoms of bvFTD:

- Disinhibition (a loss or lack of restraint based on social norms, leading to inappropriate behavior and impulsivity).

- Disinhibition includes socially inappropriate behavior such as invading interpersonal space, inappropriate touching or over-familiarity with strangers. There can be impulsive or careless actions like new onset gambling, stealing, poor decision-making without regards to the consequences (e.g. buying matching motor cycles for themselves and their 7 year old son). Disinhibition is linked to right orbital frontal cortex degeneration 30. New criminal behaviors are seen in 37%–54% of bvFTD patients 31. Loss of social decorum such as telling off color jokes, using crude language, and rudeness with lack of embarrassment is common in bvFTD. There can be dramatic change in self-awareness, with lack of insight into one’s disease 32. Behaviors may include:

- Making uncharacteristic rude or offensive comments

- Ignoring other people’s personal space

- Shoplifting, reckless spending

- Touching strangers or inappropriate sexual behavior

- Aggressive outbursts

- Disinhibition includes socially inappropriate behavior such as invading interpersonal space, inappropriate touching or over-familiarity with strangers. There can be impulsive or careless actions like new onset gambling, stealing, poor decision-making without regards to the consequences (e.g. buying matching motor cycles for themselves and their 7 year old son). Disinhibition is linked to right orbital frontal cortex degeneration 30. New criminal behaviors are seen in 37%–54% of bvFTD patients 31. Loss of social decorum such as telling off color jokes, using crude language, and rudeness with lack of embarrassment is common in bvFTD. There can be dramatic change in self-awareness, with lack of insight into one’s disease 32. Behaviors may include:

- Apathy (indifference or lack of interest in previously meaningful activities)

- Apathy can present in many ways 33. Affective apathy presents as indifference or not caring. Motor apathy manifests as decreased drive to move and less movement overall 34 whereas cognitive apathy is a loss of desire to engage in goal oriented activities 33. Symptoms of apathy may also include social withdrawal in work activities, family functions or hobbies. Patients often need prompting to stay engaged in conversation, do chores or even to move. Apathy is easily misinterpreted as depression. Atrophy in the medial prefrontal lobes and anterior cingulate have been correlated with apathy in bvFTD 35. Behaviors may include:

- Loss of interest in work, hobbies, and personal relationships

- Neglect of personal hygiene

- Loss of initiative

- Apathy can present in many ways 33. Affective apathy presents as indifference or not caring. Motor apathy manifests as decreased drive to move and less movement overall 34 whereas cognitive apathy is a loss of desire to engage in goal oriented activities 33. Symptoms of apathy may also include social withdrawal in work activities, family functions or hobbies. Patients often need prompting to stay engaged in conversation, do chores or even to move. Apathy is easily misinterpreted as depression. Atrophy in the medial prefrontal lobes and anterior cingulate have been correlated with apathy in bvFTD 35. Behaviors may include:

- Emotional blunting

- Loss of warmth, empathy, sympathy or concern for others. Behaviors may include:

- Indifference to important events (e.g., death of a family member or friend);

- Failure to recognize that loved ones are upset or unhappy

- Making cruel comments towards others

- Loss of warmth, empathy, sympathy or concern for others. Behaviors may include:

- Compulsive or ritualistic behaviors

- Single behaviors or routines that are performed over and over. These may include:

- Repeating words or phrases

- Hand rubbing, clapping

- Re-reading the same book over and over again

- Hoarding

- Walking to the same place at the same time every day

- Single behaviors or routines that are performed over and over. These may include:

- Changes in eating habits or diet

- Excessive, compulsive or inappropriate eating and drinking, or other pronounced changes in dietary preferences.

- Binge eating

- Carbohydrate craving

- Eating only specific foods

- Increased or first-time use of tobacco products

- Hyperorality

- Excessive water or alcohol consumption

- Attempting to consume inedible objects

- Excessive, compulsive or inappropriate eating and drinking, or other pronounced changes in dietary preferences.

- Deficits in executive function

- Poor decision-making, judgment, problem-solving, and organizational skills. Examples include:

- Difficulty planning the day’s activities

- Questionable financial decisions

- On-the-job mistakes that may be uncharacteristic

- Poor decision-making, judgment, problem-solving, and organizational skills. Examples include:

- Lack of insight

- As noted above, failure to recognize changes in behavior or exhibit awareness of effects of behavior on others. Behaviors may include:

- Blaming others for consequences of socially unacceptable behavior; e.g., job loss

- Anger at limitations on activities

- As noted above, failure to recognize changes in behavior or exhibit awareness of effects of behavior on others. Behaviors may include:

- Other symptoms

- Agitation, emotional instability. These may be conveyed through:

- Pacing

- Frequent and abrupt mood changes

- Agitation, emotional instability. These may be conveyed through:

Primary Progressive Aphasias

Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA) is characterized predominantly by the gradual loss of the ability to speak, read, write, and understand what others are saying.

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is diagnosed when three criteria are met:

- There is a gradual impairment of language (not just speech). Speech problems alone are not sufficient for diagnosing primary progressive aphasia (PPA). When the dominant problem is speech rather than language, the diagnosis is progressive apraxia of speech rather than primary progressive aphasia (PPA).

- The language problem is initially the only impairment.

- The underlying cause is a neurodegenerative disease.

Experts further subdivide primary progressive aphasia (PPA) into three clinical subtypes based on the specific language skills that are most affected.

- Nonfluent/Agrammatic variant PPA (nfvPPA) also called progressive nonfluent aphasia. A person has more and more trouble producing speech. Eventually, the person may no longer be able to speak at all. He or she may eventually develop movement symptoms similar to those seen in corticobasal syndrome. In this case, individuals lose grammar (the small connecting words) but have preserved language comprehension for specific items/objects. This causes speech to become effortful, hesitant, and sentence length becomes progressively truncated. Writing and language comprehension may be affected in the same manner. This subtype of PPA is usually associated with tau pathology.

- Semantic variant PPA also called semantic dementia, a person slowly loses the ability to understand single words and sometimes to recognize the faces of familiar people and common objects. Here, the meaning of specific words is lost, and both comprehension of the word and the ability to retrieve the name of an object may be lost. Speech remains fluent and grammar is good, however, paraphasias (word substitution errors) are common. This subtype of PPA is usually associated with TDP-43 pathology.

- Logopenic variant PPA, a person has trouble finding the right words during conversation but can understand words and sentences. The person does not have problems with grammar. In these individuals, speech is slow, but grammar and comprehension are less affected. Impairment in the repetition of multisyllabic words and particularly phrases is a key feature. Sound substitution (phonemic) paraphasias are also seen in this group, as in a false word that rhymes with the intended word. Logopenic aphasia is usually associated with an underlying Alzheimer’s pathology.

Nonfluent/Agrammatic Primary Progressive Aphasia

Patients with nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasias (nfvPPA) also called progressive nonfluent aphasia find it increasingly difficult to speak yet can still recall the meanings of individual words. The inability to form sounds with their lips and tongue is caused by degeneration of the parts of the brain that control certain related muscles; the muscles themselves, however, are unaffected. The technical term for such problems is apraxia of speech. As a result, their speech becomes slow and effortful (effortful speech) and they may appear to be physically struggling to produce words. Over time, the speech becomes labored, slow, slurred, and choppy with disrupted prosody. The patient begins making inconsistent speech sound errors without awareness of this deficit. There can be inconsistent insertions, deletions, distortions, and substitutions in speech sounds. If a patient is asked to repeat a complexly structured word like “catastrophe” five times in a row, he or she will demonstrate a motor speech apraxia by repeating this word differently each time 36. Improper use of grammar is frequently present in nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasias (nfvPPA), but can be subtle or even absent in the early stages of the illness. People with nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasias (nfvPPA) make many mistakes while speaking, including omitting small grammatical words, using word endings and verb tenses incorrectly, and/or mixing up the order of words in sentences. Eventually, some may develop difficulty swallowing as well as more widespread motor symptoms similar to those seen in the movement-predominant forms of FTD such as corticobasal syndrome.

Patients with nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasias (nfvPPA) can often have an aphemia (a type of aphasia characterized by the inability to express ideas in spoken words), but can still communicate correctly with written language. Eventually agrammatism will involve both verbal and written language. Effortful speech often occurs before clear apraxia of speech or agrammatism 37. The neuroanatomical correlate for the symptoms of nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasias (nfvPPA) are Broadman’s Area 44, 45 (Broca’s area) in the left inferior frontal gyrus and the anterior insula 38. As time progresses, patients will have decreased verbal output and eventually become non-verbal. Mutism in nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasias (nfvPPA) is correlated to a larger lesion expanding beyond the typical inferior frontal and insular regions involved early in nfvPPA 39.

The defining symptoms of nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasias (nfvPPA):

- Apraxia. Difficulty producing movements of lips and tongue needed for speech. This results in distorted or incorrect speech sounds with slow, labored speech, and groping movements of the face and mouth in an effort to produce the correct sound.. Effortful speech is often the first symptom. Multisyllabic words are the most difficult to produce.

- Agrammatism. Omitting words in sentences, especially short connecting words (e.g., “to,” “from,” “the.” The order of words in sentences is often incorrect. Errors are made in the use of word endings, verb tenses and pronouns. Speech becomes restricted to short, simple phrases that are difficult for listener to understand because of omissions and errors. As examples: the affected individual may use “seed” instead of “saw” or “throwed” instead of “threw.” They may say: “Today…go lunch…ah…sister” for “today I am going to lunch with my sister.”

- Impaired comprehension of complex sentences. Single-word comprehension is unaffected, but the ability to understand long or grammatically difficult sentences is reduced. Persons with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) may find it increasingly difficult to understand what they experience as “too much” verbal information, i.e. watching television or understanding conversation in a group setting.

- Mutism. The affected person does not speak at all.

- Difficulty swallowing. Develops later in the progression of the disease.

- Motor symptoms. Parkinson’s disease-like movement deficits can occur. The person affected may experience slow, stiff movement, lose balance or fall easily, have difficulty using an arm or leg, and experience restricted up-and-down eye movement.

Diagnostic criteria for nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA (nfvPPA)

- I. Clinical diagnosis of nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA:

- At least one of the following core features must be present:

- Agrammatism in language production

- Effortful, halting speech with inconsistent speech sound errors and distortions (apraxia of speech)

- At least 2 of 3 of the following other features must be present:

- Impaired comprehension of syntactically complex sentences

- Spared single-word comprehension

- Spared object knowledge

- At least one of the following core features must be present:

- II. Imaging-supported nonfluent/agrammatic variant diagnosis

- Both of the following criteria must be present:

- Clinical diagnosis of nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA

- Imaging must show one or more of the following results:

- Predominant left posterior frontoinsular atrophy on MRI or

- Predominant left posterior frontoinsular hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT or PET

- Both of the following criteria must be present:

- III. Nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA with definite pathology

- Clinical diagnosis (criterion A below) and either criterion B or C must be present:

- Clinical diagnosis of nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA

- Histopathologic evidence of a specific neurodegenerative pathology (e.g., frontotemporal lobar degeneration-tau, frontotemporal lobar degeneration-TDP [frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43], Alzheimer’s disease, other)

- Presence of a known pathogenic mutation

- Clinical diagnosis (criterion A below) and either criterion B or C must be present:

Semantic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia

Semantic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia (svPPA) also known as PPA-S, is characterized by the progressive loss of the meanings of words 40. If there are additional major problems in identifying objects or faces, the condition is also called semantic dementia. Other language skills, including the ability to produce speech and to repeat phrases and sentences spoken by others, are unaffected. However, although the affected person may continue to speak fluently, their speech becomes vague and difficult to understand because many words are omitted or substituted. As the disorder progresses, people with semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) may also exhibit changes in behavior similar to those seen in bvFTD, such as disinhibition and rigid food preferences.

If the left temporal lobe is involved, as in left svPPA, symptoms are predominantly language-based with a slow loss of semantic knowledge. When the right temporal lobe is primarily involved (right svPPA), behavioral symptoms predominate 9. As time progresses both temporal lobes become involved and symptoms begin to overlap 41. By five to seven years, patients get more frontal lobe structures involved and develop symptoms of bvFTD with disinhibition, change in food preference and weight gain 41. Patients with semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA), tend to have slow progression and can live a decade or more after symptom onset 42. Of the core clinical phenotypes in frontotemporal dementia, svPPA is the least likely to have a genetic cause underlying the etiology 43.

Right temporal svPPA patients present with prominent behavioral changes that include emotional distance, irritability, social isolation, bizarre alterations in dress, compulsions, disruption of sleep, appetite and libido 41. Patients with right temporal svPPA can often lack social pragmatics. They can be viscous, with telling long-winded stories, interrupting loved ones and not picking up on normal social cues that they may be acting inappropriately. It is thought that this inability to pick up social cues has to do with an inability to read the emotions on faces. Worsening degrees of right amygdala atrophy has been correlated with impairment in processing facial emotions 44.

Patients with either left or right temporal svPPA can have new compulsions. Left svPPA patients have been shown to have compulsions directed towards visual or non-verbal stimuli where objects are devoid of verbal information like coins or pictures. Right svPPA have compulsions around games with words and symbols 41.

An interesting phenomenon is the development of new artistic abilities that has been observed in svPPA. Left svPPA patients have developed new visual abilities in painting, drawing, music, and gardening 45. Right svPPA patients can have emergent abilities in writing despite their progressive neurodegenerative condition 46. One patient with bilateral, right worse than left, svPPA was studied in depth at UCSF. As the right temporal lobe became more involved, he showed decline in emotional perception displayed through his new skill of painting 47. The topics of the painting would show couples and landscapes, but as his disease progressed the facial expressions became less genuine. Painted couples would stand next to each other, not holding hands, with bizarre smiles showing teeth 47. One could theorize that this case illustrates the difficulty the patient had understanding emotions in others as the right temporal lobe involvement progressed.

Semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) clinical features

- Anomia. An inability to recall the names of objects; difficulty “finding the right word.” The person affected may not be able to name a picture of a truck, or may substitute another word in the same category such as “car” for “truck.”

- Reduced single-word comprehension. The person affected is unable to recall what words mean, especially words that are less familiar or less frequently used. For example, she or he may ask “What is a truck?” When asked to bring an orange, the patient may come back with an apple because the meaning of the word ‘orange’ is lost. This does not mean that the object is not recognized, as shown by the fact that the patient will not try to eat an orange without peeling it.

- Impaired object knowledge. Being unable to remember what a familiar object is or how it is used. For example, the person affected may be unable to identify common kitchen utensils and how they are used in cooking. This is very unusual at initial stages of semantic PPA but may appear later.

- Surface dyslexia/dysgraphia. Difficulty reading and writing words that do not follow pronunciation or spelling rules; such words are spelled or spoken “as if” they followed the rules. For example, the person affected may write “no” instead of “know,” or read “broad” as “brode.”

The initial features of classic left temporal semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) are anomia and single word comprehension deficits 37. The earliest symptom is often poor comprehension of single low frequency words such as “giraffe” with initial preservation of higher frequency words like “dog”. As symptoms progress, patients also lose semantic knowledge about objects 37, so if a patient does not know the word “giraffe,” they will not improve with phonemic cues or semantic hints like “animal with a long neck.” When svPPA patients are asked to read irregularly spelled words (yacht, gnat), they will sound them out, attempting phonetic “regularization”, having lost the knowledge or their unconventional sound (i.e. y-act, ga-nat), a phenomenon known as surface dyslexia 37. In svPPA, repetition is spared, speech apraxia is not present, and syntax and grammar remain impressively intact. If the mesial temporal lobes are involved, memory can be affected but executive function and visuospatial skills typically are preserved 48. Clinical research criteria for language predominant (left) svPPA must include the core features of impaired confrontational naming and impaired single word comprehension. There also must be three of the following four criteria: impaired object knowledge, surface dyslexia, spared repetition, and spared speech production 37.

Diagnostic criteria for semantic variant PPA (svPPA)

- I. Clinical diagnosis of semantic variant PPA

- Both of the following core features must be present:

- Impaired confrontation naming

- Impaired single-word comprehension

- At least three of the following other diagnostic features must be present:

- Impaired object knowledge, particularly for low-frequency or low-familiarity items

- Surface dyslexia or dysgraphia

- Spared repetition

- Spared speech production (grammar and motor speech)

- Both of the following core features must be present:

- II. Imaging-supported semantic variant PPA diagnosis

- Both of the following criteria must be present:

- Clinical diagnosis of semantic variant PPA

- Imaging must show one or more of the following results:

- Predominant anterior temporal lobe atrophy

- Predominant anterior temporal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT or PET

- Both of the following criteria must be present:

- III. Semantic variant PPA with definite pathology

- Clinical diagnosis (criterion A below) and either criterion B or C must be present:

- A. Clinical diagnosis of semantic variant PPA

- B. Histopathologic evidence of a specific neurodegenerative pathology (e.g., frontotemporal lobar degeneration-tau, frontotemporal lobar degeneration-TDP [frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43], Alzheimer’s disease, other)

- C. Presence of a known pathogenic mutation

- Clinical diagnosis (criterion A below) and either criterion B or C must be present:

Logopenic Variant PPA

Logopenic Variant PPA (lvPPA) also known as PPA-L have difficulty finding words when they are speaking. As a result, they may speak slowly and hesitate frequently as they search for the right word. Unlike people with semantic variant PPA, however, they are still able to recall the meanings of words. Unlike people with agrammatic PPA, speech can be perfectly fluent during small talk but then becomes hesitant and halting when the person needs to be specific or use a more unfamiliar word. Speech is usually not effortful or distorted. The logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA) is also characterized by a narrow attention span for words that compromise the ability to repeat phrases and sentences. As the disease progresses, affected individuals may develop problems comprehending complex sentences.

Logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA) clinical features:

- Impaired single-word retrieval. Difficulty finding the right word while speaking.

- Pauses and hesitations due to time needed for word retrieval

- Extended description (circumlocution) may be substituted for a forgotten word

- Impaired repetition. More difficulty with longer phrases and sentences.

- Phonological speech errors. Mistakes in speech sounds, including omissions and substitutions. For example, the person affected may substitute sounds made with the tip of the tongue such as “t” or “d” for sounds made near the throat such as “k” or “g”: “tup” instead of “cup” or “dap” instead of “gap.” They may omit final consonants: “slee” instead of “sleep.”

- Phonological paraphasias. Substitution of a non-word with some of the same sounds for a legitimate word. For example, the person affected may say “lelephone” for “telephone.”

- Poor comprehension of complex sentences. With single-word comprehension spared.

- Difficulty swallowing. May develop later in the progression of the disease.

Diagnostic criteria for logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA)

Doctors will consider a diagnosis of logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA) based on the following symptoms:

- Impaired single-word retrieval in spontaneous speech

- Impaired repetition of phrases and sentences

AND at least three of the following:

- Phonological speech errors

- Single-word comprehension and object knowledge unaffected

- Physical ability to form words (motor speech) unaffected

- Simple but correct grammar

Corticobasal syndrome

Corticobasal syndrome belongs to the category of FTD disorders that primarily affect movement. To meet the most recent clinical criteria for probable corticobasal syndrome, a patient must have an asymmetric presentation with two of the following motor symptoms: limb rigidity or akinesia, limb dystonia, or limb myoclonus, as well as two of the following higher cortical symptoms: orobuccal or limb apraxia, cortical sensory deficit, or alien limb phenomena 50. A person affected by corticobasal syndrome may present with cognitive, motor, or language symptoms as the first sign 51. Development of a second and/or third category of symptoms makes it easier for the physician to recognize the illness as corticobasal syndrome. Individuals with corticobasal syndrome are easier to diagnose if they are showing limb apraxia, such as no longer being able to use the remote control for the television set, or not being able to retrieve mail from the mailbox. Initial symptoms of corticobasal syndrome often begin around age 60 (although there is variability in the age of onset) and then become bilateral as the disease progresses. A person with corticobasal syndrome may first present with a language disorder and develop motor symptoms over time.

Movement deficits in corticobasal syndrome often begin on one side of the body, but eventually both sides are affected. In addition to motor symptoms, people with corticobasal syndrome may exhibit changes in behavior and language skills common to bvFTD and PPA, particularly as the disease progresses.

Some symptoms of both corticobasal syndrome and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), another FTD disorder associated with a decline in motor function, resemble those often seen in people with Parkinson’s disease. These features are sometimes referred to as “atypical Parkinsonism.”

Like all FTD disorders, corticobasal syndrome is associated with degeneration of the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes. In addition, several regions deeper in the brain that play important roles in initiating, controlling, and coordinating movement are also affected.

The term corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is applied to cases which have a particular type of tauopathy at autopsy. Some cases of corticobasal syndrome prove to have Alzheimer’s pathology instead.

Signs and symptoms of corticobasal syndrome include:

- Limb Apraxia

- Inability to compel a hand, arm, or leg to carry out a desired motion although the muscle strength needed to complete the action is maintained

- Difficulty completing familiar purposeful activities, such as opening a door, operating the television remote, or using kitchen tools

- Tripping or falling

- Akinesia/bradykinesia. Absence (akinesia) or abnormally slow (bradykinesia) movement.

- Rigidity. Stiffness, resistance to movement.

- Dystonia. Uncontrollable muscle contraction that causes an arm or leg to twist involuntarily or to assume an abnormal posture.

- Cognitive symptoms. These may include:

- Alien limb phenomenon – sensation that an arm or leg is not part of the body, accompanied by inability to control movement of the limb

- Acalculia – inability to carry out simple mathematical calculations, such as adding or subtracting

- Visuospatial deficits – difficulty orienting in space.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) previously known as Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome, belongs to the category of frontotemporal dementia that primarily affect movement. Some symptoms of both progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal syndrome, another FTD disorder associated with a decline in motor function, resemble those often seen in people with Parkinson’s disease. These features are sometimes referred to as “atypical Parkinsonism.”

The earliest motor symptoms are stiffness in the axial muscles, the neck and trunk, along with poor balance and more frequent falls. The earliest visual signs are a decrease in upward vertical movement of the eyes (vertical saccades) and a progressive inability to move the eyes, including opening or closing the eyes. progressive supranuclear palsy can also affect coordination, and movement of the mouth, tongue, and throat. In addition to motor symptoms, people with progressive supranuclear palsy may exhibit changes in behavior and language skills common to bvFTD and PPA, particularly as the disease progresses.

Patients can present with predominant executive dysfunction, personality changes, reduced mental speed and attention deficits giving a more frontal behavior syndrome that is not emphasized in the current progressive supranuclear palsy criteria 52. Patients presenting with frontal behavior symptoms and without falls or supranuclear gaze palsy in their first year of presentation are likely to be among the 20% of progressive supranuclear palsy patients that are clinically misdiagnosed 53. Clinical presentations of bvFTD or nfvPPA can progress to progressive supranuclear palsy or alternatively, an initial presentation of progressive supranuclear palsy can progress into bvFTD or nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasias (nfvPPA) 54. Williams 53 has proposed a system to further differentiate progressive supranuclear palsy. He classifies Richardson’s syndrome as the classic PSP-S described above. PSP-Parkinsonism (PSP-P), is the most common non Steele-Richardson PSP subtype, which is similar to Richardson’s syndrome but has tremor and mild responsiveness to Levodopa. PSP-pure akinesia with gait freezing (PSP-PAGF) is a PSP-S subtype which can have a slower disease course in spite of severe atrophy in the globus pallidus, substantia nigra and subthalamic nucleus. There are also PSP-Corticobasal Syndrome (PSP-CBS) as well as PSP-progressive nonfluent aphasia (PSP-PNFA) 53.

The 1996 consensus clinical research criteria for possible progressive supranuclear palsy defines the following core features 55:

- onset after age 40,

- gradual progression,

- either vertical supranuclear gaze palsy or slow vertical saccades, and

- postural instability with falls in the first year.

Patients must also have no exclusion criteria. Probable progressive supranuclear palsy is inclusive of both a vertical supranuclear gaze palsy and postural instability with falls 55. Severe impairment of postural reflexes and bradykinesia make progressive supranuclear palsy falls extremely dangerous since patients are often unable to protect themselves from objects during the fall. The falls in progressive supranuclear palsy can be multifactorial from either the impaired eye movements, postural instability, impulsivity or all three symptoms.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) clinical features

- Supranuclear gaze palsies. The person affected may experience an inability to move or aim the eyes vertically (particularly downward) or horizontally (left and right). They may experience rapid involuntary eye movements, or difficulty blinking or excessive blinking. Supranuclear gaze palsies may be experienced as blurring. The person affected may experience difficulty reading, make poor eye contact during conversations, have difficulty going down stairs, or experience impaired vision while driving.

- Postural instability. Difficulty maintaining balance, which can lead to frequent, unexplained falls.

- Gait instability. An unsteady, awkward gait.

- Akinesia/bradykinesia. Absence of movement (akinesia) or abnormally slow (bradykinesia) movement.

- Rigidity. Stiffness, resistance to movement.

- Dysphagia. Difficulty swallowing, including gagging or choking. This can lead to aspiration pneumonia.

- Dysarthria. Slurred or slowed speech due to difficulty moving the muscles controlling the lips, tongue and jaw.

- Behavioral and emotional symptoms that may occur in progressive supranuclear palsy:

- A progressive deterioration in the diagnosed person’s ability to control or adjust their behavior appropriately in different social contexts is the hallmark of the behavior changes, and results in the embarrassing, inappropriate social situations that can be one of the most disturbing facets of FTD and related disorders.

- In addition to the depression, apathy and inability to control emotions noted above, progressive supranuclear palsy patients may manifest emotional blunting or indifference toward others and a lack of insight into changes in their own behavior.

- Cognitive symptoms. Progressive supranuclear palsy patients may suffer increasing impairment in “executive functions,” such as distractibility, mental rigidity and inflexibility, impairments in planning and problem solving, and poor financial judgment. progressive supranuclear palsy patients may also have memory problems. They also develop progressive language disturbance.

Frontotemporal dementia and Motor Neuron Disease

FTD-ALS (frontotemporal dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) is a combination of bvFTD and ALS (commonly called Lou Gehrig’s disease). Symptoms include the behavioral and/or language changes seen in bvFTD as well as the progressive muscle weakness seen in ALS. Symptoms of either disease may appear first, with other symptoms developing over time. 15% of FTD patients and up to 30% of patients with motor neuron disease experience overlap between the two syndromes 56. The coexistence of two disorders may be under recognized, as patients tend to present to either a neuromuscular disease clinic or a dementia clinic 57. To meet criteria for motor neuron disease, an frontotemporal dementia patient needs upper and lower motor neuron signs on physical examination or electromyogram (EMG) 58. The El Escorial criteria are one of the most widely accepted criteria for the diagnosis of ALS but the Awaji criteria are also used which deemphasizes the use of EMG to make an earlier diagnosis 58. If an frontotemporal dementia patient presents with fasciculations, muscle weakness, trouble swallowing, spastic tone, hyperreflexia, or pathological laughing or crying, this should raise concern for motor neuron disease and prompt a neuromuscular work up. If patients with ALS presents with symptoms concerning for bvfrontotemporal dementia, this should prompt a cognitive work up. There is a shorter survival in patients with both frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease since patients with frontotemporal dementia symptoms are less compliant with standard ALS treatments 59. Mutations in certain genes have been found in some patients with FTD-ALS.

As many as 20% of frontotemporal dementia patients develop signs of motor neuron disease (MND). Likewise approximately half of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients develop some fronto-executive problems 60. A smaller number of these patients develop full-blown FTD-ALS. It is now recognized that the C9orf72 gene is the most common gene causing hereditary FTD, ALS and ALS with FTD (see Genetics section).

With or without the gene expansion, the addition of motor neuron disease to frontotemporal dementia is a compromising factor which greatly reduces median survival to less than 3 years 61. Behavioral symptoms complicate the management of dysphagia as well as respiratory dysfunction as respiration therapy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tubes are not well tolerated by the patient. PEG shows little survival benefit 62.

Although significant phenotypic heterogeneity exists among C9orf72 carriers, the majority present with either bvFTD or FTD-ALS. PPA variants including nonfluent/agrammatic and semantic are rare. Prominent psychosis with delusions and hallucinations are relatively common 63). Research into the clinical features associated with the C9orf72 mutation is active and on-going.

Frontotemporal dementia symptoms

Signs and symptoms of frontotemporal dementia can be different from one individual to the next. Signs and symptoms get progressively worse over time, usually over years. Clusters of symptom types tend to occur together, and people may have more than one cluster of symptom types.

Signs of frontotemporal dementia can include:

- Personality and behavior changes – acting inappropriately or impulsively, appearing selfish or unsympathetic, neglecting personal hygiene, overeating, or loss of motivation

- Language problems – speaking slowly, struggling to make the right sounds when saying a word, getting words in the wrong order, or using words incorrectly

- Problems with mental abilities – getting distracted easily, struggling with planning and organisation

- Memory problems – these only tend to occur later on, unlike more common forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease

There may also be physical problems, such as slow or stiff movements, loss of bladder or bowel control (usually not until later on), muscle weakness or difficulty swallowing.

These problems can make daily activities increasingly difficult, and the person may eventually be unable to look after themselves.

Behavior and personality changes

Many people with frontotemporal dementia develop a number of unusual behaviors they’re not aware of. The most common signs of frontotemporal dementia involve extreme changes in behavior and personality. These can include:

- being insensitive or rude

- increasingly inappropriate social behavior

- acting impulsively or rashly

- loss of inhibitions

- lack of judgment

- seeming subdued

- losing interest (apathy) in people and things, which can be mistaken for depression

- losing drive and motivation

- inability to empathise with others, seeming cold and selfish

- repetitive compulsive behaviors, such as humming, smacking lips, hand-rubbing, clapping and foot-tapping, or routines such as walking exactly the same route repetitively

- a change in food preferences, such as suddenly liking sweet foods, overeating and poor table manners

- eating inedible objects

- compulsively wanting to put things in the mouth

- compulsive eating, alcohol drinking and/or smoking

- neglecting personal hygiene

As the condition progresses, people with frontotemporal dementia may become socially isolated and withdrawn.

Speech and language problems

Some subtypes of frontotemporal dementia lead to language problems or impairment or loss of speech. Primary progressive aphasia, semantic dementia and progressive agrammatic (nonfluent) aphasia are all considered to be frontotemporal dementia.

Problems caused by these conditions include:

- Increasing difficulty in using and understanding written and spoken language, such as having trouble finding the right word to use in speech or naming objects

- Trouble naming things, possibly replacing a specific word with a more general word such as “it” for pen

- Using words incorrectly – for example, calling a sheep a dog

- No longer knowing word meanings

- Forgetting the meaning of common words

- Loss of vocabulary

- Having hesitant speech that may sound telegraphic

- Making mistakes in sentence construction

- Difficulty making the right sounds to say words

- Repeating a limited number of phrases

- Slow, hesitant speech

- Getting words in the wrong order

- Automatically repeating things other people have said

Some people gradually lose the ability to speak, and can eventually become completely mute.

Problems with mental abilities

Problems with thinking do not tend to occur in the early stages of frontotemporal dementia, but these often develop as the condition progresses. These can include:

- difficulty working things out and needing to be told what to do

- poor planning, judgement and organization

- becoming easily distracted

- thinking in a rigid and inflexible way

- losing the ability to understand abstract ideas

- difficulty recognizing familiar people or objects

- memory difficulties, although this is not common early on

Dysexecutive syndrome

Another frontotemporal dementia subtype is the dysexecutive syndrome. Here, an affected individual suffers from problems with complex reasoning and problem solving. Planning, sequencing and goal- directed behavior are involved. Problems with controlling attention and disinhibition underlie the syndrome; individuals can become stimulus-bound. These individuals cannot multitask, and they need guidance to remain on simple tasks including basic activities of daily living. In contrast, memory testing remains close to normal and these individuals may do well on simple mental status tests.

Motor disorders

Rarer subtypes of frontotemporal dementia are characterized by problems with movement similar to those associated with Parkinson’s disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Motor-related problems may include:

- Tremor

- Rigidity

- Muscle spasms or twitches

- Slow, stiff movements, similar to Parkinson’s disease

- Poor coordination

- Difficulty swallowing

- Loss of bladder control

- Loss of bowel control

- Muscle weakness

- Inappropriate laughing or crying

- Falls or walking problems

Some people have frontotemporal dementia overlapping with other neurological (nerve and brain) problems, including:

- motor neurone disease – causes increasing weakness, usually with muscle wasting

- corticobasal degeneration – causes problems controlling limbs, loss of balance and co-ordination, slowness and reduced mobility

- progressive supranuclear palsy – causes problems with balance, movement, eye movements and swallowing.

Frontotemporal dementia complications

According to survey-based studies, sleep, or nighttime behavior disturbance is demonstrated by 33%-76% of patients with frontotemporal dementia. these are more likely to be reported in patients with primary progressive aphasia than behavior variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). Similar is the case in the caregivers of primary progressive aphasia patients. All sleep disorders require sleep hygiene and routine maintenance. Also, there is a risk of an overlapping syndrome with frontotemporal dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia-motor neuron disease, frontotemporal dementia-progressive supranuclear palsy, and frontotemporal dementia-amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. All require both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches as well as treatment of underlying disease.

- Insomnia: reported in 48% of cases

- Sleep-disordered breathing: reported in 68% of cases 64

- Excessive daytime sleepiness: reported in 64% of cases

- Restless leg syndrome: reported in 8% of cases

- Risk of falls 65

- Hypersexuality

- Eating disorders, (such as hyperphagia/binge eating, lack of appetite, a particular food preference) 66

Frontotemporal dementia causes

In frontotemporal dementia, the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain shrink. In addition, there is an abnormal buildup of altered brain proteins in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. What causes these changes is usually unknown. In about 60% of people, they are often the first person is their family to be affected by frontotemporal degeneration. These people are classified as having a sporadic or nonfamilial form of the frontotemporal dementia. Researchers do not know why these people have developed frontotemporal degeneration. Their family members do not appear to be at an increased risk of developing the disorder. However, there is a strong genetic component to frontotemporal degeneration. In about 40% percent of cases there is a history of neurodegeneration or psychiatric illness in the family 12. In some of these people, the cause of the disorder is unknown. Researchers do not know whether there is an altered gene in these families, but the disorder occurs with more frequency than it otherwise would by chance. One theory is that, in these families, frontotemporal degeneration occurs because of the interaction of multiple factors (multifactorial cause). This might mean that there is a gene or genes that cause people to be more likely (predisposed) to develop a disorder, but the disorder will not develop unless these gene(s) are triggered or “activated” under certain circumstances such as particular environmental factors. However, despite research, no evidence has been found linking any potential environmental factor to the development of frontotemporal degeneration. There is no known risk factor for the disorder other than a family history of frontotemporal degeneration or a similar disorder. Recently, researchers have confirmed shared genetics and molecular pathways between frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). More research needs to be done to understand the connection between these conditions, however.

The two most common proteins involved are the tau protein and the transactive response DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43). These proteins are normally found in the brain. Their specific functions are complex and not fully understood. However, these proteins are critical to the proper health and function of nerve cells (neurons). In individuals with frontotemporal dementia these proteins are misfolded (misshapen); as a result, they clump together. As these protein clumps, or aggregates, build up in the brain, they interfere with or disrupt the normal functioning of nerve cells, which ultimately die. Nerve cell death within the frontal and temporal lobes causes these areas of the brain shrink (atrophy).

These clumps of misfolded proteins may be referred to as “bodies” or “inclusions”. So the terms, tau bodies or tau inclusions, refer to nerve cells that contain these clumps of misfolded proteins. These inclusions may have distinctive features even when the same protein is involved. For examples, Pick’s disease refers to distinctive, round, silver-staining inclusions called Pick’s bodies. Most inclusions associated with frontotemporal dementia contain either variations of tau protein or TDP-43.

In about 10-25% of people diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, an altered gene has been identified. Mutations in over 20 genes have been identified in the possible development of frontotemporal dementia 4. Genes provide instructions for creating proteins that play a critical role in many functions of the body. When an alteration of a gene occurs, the protein product may be faulty, inefficient, or absent. Depending upon the functions of the particular protein, this can affect many organ systems of the body, including the brain.

The major genes that have been linked to frontotemporal degeneration include the MAPT gene (microtubules associated protein tau gene located on chromosome 17q21.32), GRN gene (granulin gene on chromosome 17q21.32) and hexanucleotide repeat expansion of the chromosome 9 open-reading-frame 72 (C9orf72) gene on chromosomal location 9p21.2 (responsible for cytoskeleton organization) 13, 14. The MAPT gene provides instructions for making a protein called tau. This protein is found throughout the nervous system, including in nerve cells (neurons) in the brain. It is involved in assembling and stabilizing microtubules, which are rigid, hollow fibers that make up the cell’s structural framework (the cytoskeleton). Microtubules help cells maintain their shape, assist in the process of cell division, and are essential for the transport of materials within cells. The GRN gene produces the brain protein known as progranulin, which is important for optimal functioning of the protein TDP-43. Progranulin appears to be critical for the survival of nerve cells (neurons). The C9ORF72 gene also produces a protein that is found in nerve cells although its role in not well understood. It is also postulated that C9orf72 gene mutation is a continuum between frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and is responsible for the occurrence of both entities. These three genes account for the majority of people with inherited frontotemporal degeneration. In rare instances, additional genes have been identified as causing frontotemporal degeneration including the VCP, TARDBP, FUS, CHMP2B and TBK1 genes.

The altered genes that cause frontotemporal degeneration are usually inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Genetic diseases are determined by the combination of genes for a particular trait that are on the chromosomes received from the father and the mother. Dominant genetic disorders occur when only a single copy of an abnormal gene is necessary for the appearance of the disease. The altered gene can be inherited from either parent, or can be the result of a new mutation (gene change) in the affected individual. The risk of passing the abnormal gene from affected parent to offspring is 50% for each pregnancy regardless of the sex of the resulting child. If you have a family history of frontotemporal dementia, you may want to consider talking to your doctor about being referred to a geneticist and possibly having a genetic test to see if you’re at risk.

Head trauma and thyroid disease have been linked with the development of frontotemporal dementia with a 3.3-fold higher risk and 2.5-fold higher risk, respectively 4.

Is Frontotemporal dementia hereditary?

In the majority of cases, frontotemporal dementia is not being inherited within the family 67. However, people with both inherited and sporadic (not inherited) frontotemporal lobe dementia exhibit the same clinical symptoms, which makes evaluation of the family history the most sensitive tool for determining the likelihood of a genetic cause.

While scientists have found gene mutations that are linked to frontotemporal lobe dementia, most cases of frontotemporal lobe dementia are sporadic, meaning that there is no known family history of frontotemporal lobe dementia. Current genetic research shows that if a diagnosed individual has no family history of frontotemporal lobe dementia or related neurological conditions, there is less than a 10% chance that they carry a mutation in a currently known frontotemporal lobe dementia gene.

However, approximately 40% of individuals with frontotemporal lobe dementia do have a family history that includes at least one other relative who also has or had a neurodegenerative disease. In approximately 15-40% of all frontotemporal lobe dementia cases, a genetic cause (e.g., a gene mutation) can be identified as the likely cause of the disease and in most cases it is an inherited mutation.