Glucagonoma

Glucagonoma is a very rare islet cell tumor of the pancreas that produces a hormone called glucagon. Glucagonoma is usually cancerous (malignant). Some glucagonomas grow slowly and don’t spread to other parts of the body. Others can spread to other parts of the body (metastases).

The most common places where glucagonomas spread to is the:

- liver

- lymph nodes

- bones

- lungs

Glucagonomas are very rare tumors that occur once in 20 to 30 million person-years 1. Around 1 out of every 100 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) about 1% diagnosed every year are glucagonomas 2. Glucagonomas arise from the alpha or A islet cells of the pancreas. Glucagonomas are typically large (greater than 3 cm) and located mainly in the tail or the body of the pancreas due to the high prevalence of alpha cells in this area 3. Over 50% are metastatic at the time of diagnosis. The incidence of glucagonoma in males and females is similar. Most patients with glucagonoma present in the fifth to sixth decade of life 3.

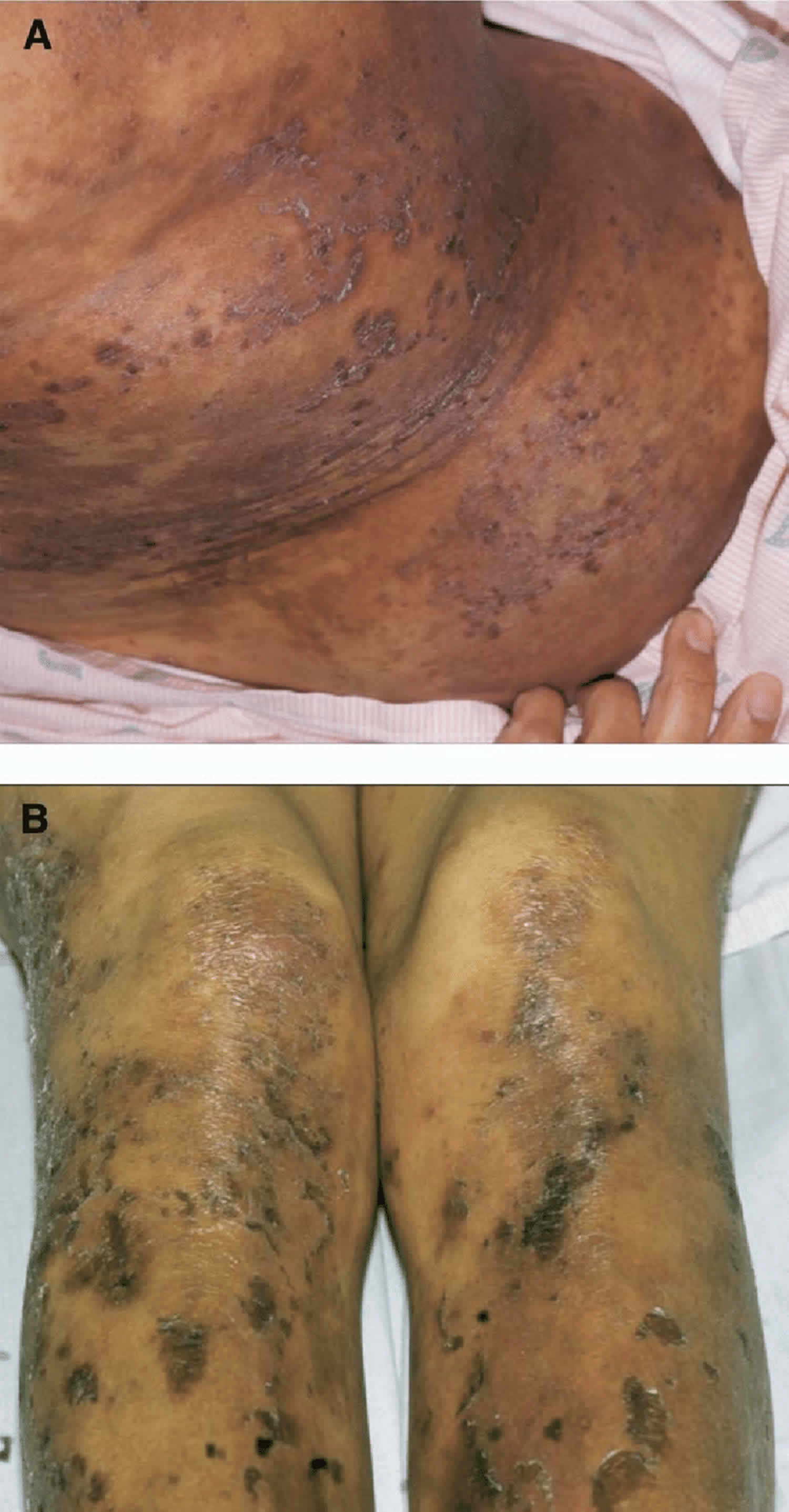

Glucagon is a 29-amino-acid single chain polypeptide. Glucagon primary function is to promote gluconeogenesis (a metabolic pathway that results in the generation of glucose from certain non-carbohydrate carbon substrates), glycogenolysis (biochemical breakdown of glycogen to glucose) and ketogenesis (production of ketone bodies through breakdown of fatty acids and ketogenic amino acids). Glucagon also stimulates the secretion of insulin and promotes lipolysis (breakdown of fats and other lipids by hydrolysis to release fatty acids) in adipose tissues. The release of glucagon is stimulated by consumption of a high-protein meal, hypoglycemia, starvation, and stress. The result of glucagon excess is hyperglycemia (high blood sugar level). High blood sugar level can cause problems with metabolism and tissue damage.The relatively mild diabetes mellitus usually does not require insulin administration for control of blood sugar levels. Patients with pancreatic glucagonoma tumors that produce excess glucagon exhibit a characteristic rash known as necrolytic migratory erythema (Figure 1).

Excessive secretion of glucagon from the tumor leads to the glucagonoma syndrome. Classic glucagonoma syndrome consists of weight loss, necrolytic migratory erythema (NME), diabetes, and mucosal abnormalities including stomatitis, cheilitis, and glossitis 4. Diabetes results secondary to the direct effects of glucagon. Diarrhea may occur from increased glucagon levels and co-secretion of gastrin, VIP (vasoactive intestinal peptide), serotonin, or calcitonin.

The characteristic necrolytic migratory erythema rash is pathognomonic, and the clinical picture should lead one to the diagnosis. The precise cause of necrolytic migratory erythema is not known, but it is thought secondary to a combination of poor nutrition, low zinc, and amino acid levels. An elevated serum glucagon level above 190 pg/mL confirms the diagnosis. Metastases are present in 60% to 80% of cases at the time of diagnosis. Most glucagonomas are solitary tumors and typically occur in the body or tail of the pancreas. Localization is not often a problem because these tumors are usually 4 to 10 cm in diameter and readily identified by CT.

Because glucagonomas are potentially malignant tumors, they should be treated as such with resection with clear margins rather than by enucleation. Surgery to remove the glucagonoma tumor is usually recommended. Glucagonoma does not usually respond to chemotherapy.

The only chance for glucagonoma cure is complete surgical resection. Before operation, preparations should include control of blood sugar levels, nutritional assessment, and alimentation as necessary. Perioperative prophylaxis with subcutaneous heparin is indicated. Some have suggested that octreotide, because it decreases the circulating glucagon levels, may allow for improved preoperative nutritional benefit of alimentation, healing of rash, and reduced risk of thromboembolism 5. Resection of the rash results in resolution of the necrolytic migratory erythema rash within a few weeks. Similarly, lost body weight returns.

Figure 1. Glucagonoma skin rash (necrolytic migratory erythema)

Footnote: The characteristic rash associated with a glucagonoma, necrolytic migratory erythema, demonstrated in these photographs of the trunk (A) and legs (B) resolves rapidly after removal of the tumor.

[Source 6 ]Glucagonoma causes

The cause of glucagonoma is unknown. Genetic factors play a role in some cases. A family history of the syndrome multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN I) is a risk factor. However, less than 10% of them have been associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 syndrome (MEN 1) 7.

Glucagonomas are neuroendocrine tumors originating from multipotential stem cells of endodermal origin. They arise from the alpha cells of the islets in the pancreas. Most glucagonomas are solitary.

Glucagonoma symptoms

Glucagonoma makes glucagon, a hormone that increases glucose (sugar) levels in the blood. Symptoms of glucagonomas usually develop slowly. Some people are only diagnosed with a glucagonoma some years after developing their first symptom. Most of the symptoms that can be caused by a glucagonoma are mild and are more often caused by something else.

Symptoms of glucagonoma may include any of the following:

- Glucose intolerance (body has problem breaking down sugars)

- High blood sugar (hyperglycemia)

- Diarrhea

- Excessive thirst (due to high blood sugar)

- Frequent urination (due to high blood sugar)

- Increased appetite

- Inflamed mouth and tongue

- Nighttime (nocturnal) urination

- Skin rash on face, abdomen, buttocks, or feet that comes and goes, and moves around

- Weight loss

- Blood clots

In most cases, the cancer has already spread to the liver when it is diagnosed.

Excess glucagon can raise blood sugar, sometimes leading to diabetes. This can cause symptoms such as feeling thirsty and hungry, and having to urinate often.

People with glucagonoma can also have problems with diarrhea, weight loss, hypercalcemia, glossitis, thromboembolic disease (blood clotting disease) and malnutrition 6. Approximately 90% of patients have lost more than 5 kg of body weight 8. Muscle wasting appears to be out of portion to tumor burden and may be related to the severe decrease in plasma amino acid concentrations seen in these patients 9. An increased risk of thromboembolic disease is attributed to increased production of factor X by pancreatic A islet cells 10. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli are not uncommon and can be fatal. The nutrition problems can lead to symptoms like irritation of the tongue and the corners of the mouth.

Glucagonoma skin rash

The symptom that brings most people with glucagonomas to their doctor is a rash called necrolytic migratory erythema (see Figure 1). The glucagonoma rash usually starts with small circles of redness which develop into itchy, painful blisters. Necrolytic migratory erythema is a red rash with swelling and blisters that often travels from place to place on the skin. The glucagonoma rash is itchy and generally begins on the extremities before spreading to the truck and face. Although necrolytic migratory erythema is a characteristic feature of glucagonoma, it is often not recognized for what it is. It may have been present for 1 to 6 years before the diagnosis is made 11. The glucagonoma skin rash is often misdiagnosed as psoriasis, eczema, or zinc deficiency.

The glucagonoma skin rash can affect most parts of the body but is more common in the:

- buttocks

- groin

- back passage (anal area)

- the sexual organs such as the penis and vagina (genitals)

- lower part of the legs

Between 70 and 90 out of every 100 people with glucagonoma (70 to 90%) have necrolytic migratory erythema.

Weight loss

You may lose a lot of weight even if you’re not dieting. More than 90 out of every 100 people with glucagonoma (more than 90%) lose weight.

Diabetes

Some people have high blood sugar levels. This causes:

- thirst

- passing a lot of urine

- weakness

- weight loss and hunger

Between 40 and 90 out of every 100 people with glucagonoma (40 and 90%) have diabetes.

Mouth ulcers

You might have broken areas of skin (ulcers) in the mouth that causes pain or discomfort. Between 30 and 40 out of every 100 people with glucagonoma (30 to 40%) have a sore mouth.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea means having more than 3 watery poos (stools) in a 24 hour period. You might also have diarrhea at night and problems controlling your bowels (incontinence).

This happens to about 15 out of every 100 people with glucagonoma (15%).

Blood clots

Blood clots might develop in the deep veins of the body. This is called deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Symptoms of blood clots include:

- pain, redness and swelling around the area where the blood clot is

- the area around the clot may feel warm to touch

Blood clots can also develop in a blood vessel in your lungs. This is a pulmonary embolism (PE). Symptoms of PE include:

- pain in your chest or upper back

- difficulty breathing

- coughing up blood

Blood clots can be serious. See your doctor straight away if you have any of these symptoms.

Mood changes

Mood changes include feeling depressed and agitated.

Anemia

Anemia or low levels of red blood cells in your blood can make you feel very tired and breathless.

Anemia happens in up to 80 out of every 100 people with glucagonoma (80%).

Glucagonoma diagnosis

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam and ask about your medical history and symptoms.

Glucagonoma should be suspected in patients with glucagonoma skin rash (necrolytic migratory erythema) associated with or without the other symptoms discussed above.

- A fasting plasma glucagon level should be drawn. Fasting plasma glucagon levels are abnormally elevated usually greater than 500 pg/mL. Normal fasting plasma glucagon levels are less than 150 pg/mL. It is important to note that different glucagon assays may exhibit variable cross-reactivity with different isoforms of glucagon, not all of which (nearly 70%) are biologically active. Serial measurements should, therefore, always be performed using the same assay directed against the C-terminus.

- Serum concentrations of amino acids and zinc should be checked to evaluate the nutritional status. The laboratory abnormalities with glucagonoma can include hypoaminoacidemia (due to targeting of amino acids into metabolic pathways in the liver by excessive hyperglucagonemia) and low zinc levels.

- A complete blood count (CBC) should be obtained to check for concurrent normocytic anemia. A comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) should be checked to detect other metabolic abnormalities.

- Obtaining serum parathyroid hormone, gastrin, insulin, pancreatic polypeptide, serotonin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), prolactin and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels is important as glucagonoma can rarely be associated with the MEN1 syndrome.

- Skin biopsy of the glucagonoma skin rash (necrolytic migratory erythema) lesion shows small bullae consisting of acantholytic epidermal cells along with lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate. The dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with an intact epidermis.

Tests that may be done include:

- CT scan of the abdomen. A CT scan can show up a glucagonoma and see whether it has spread anywhere else in the body.

- MRI scan. An MRI scan takes detailed pictures of your body. You might have an MRI scan to check if the glucagonoma has spread to other parts of the body such as the liver and lymph nodes.

- Glucagon level in the blood

- Glucose level in the blood

- Endoscopy. This test looks at the inside of your food pipe, stomach and bowel. Your doctor uses a long flexible tube which has a tiny camera and a light on the end of it. Doctors can take samples of any abnormal areas (biopsies).

- Radioactive scans. These are octreotide scans (or octreoscans) or gallium PET scans. You have an injection of a low dose radioactive substance, which is taken up by some NET cells. The cells then show up on the scan.

- Endoscopic ultrasound scan (EUS). This test combines an ultrasound and endoscopy to look at the inside at your food pipe, stomach, pancreas and bile ducts. Your doctor uses a long flexible tube (endoscope) with a tiny camera and light on the end. It also has an ultrasound probe. The ultrasound helps the doctor find areas that might be cancer. They then can take samples (biopsies) of any abnormal areas.

Blood tests

Blood tests can check your general health. They can also check the levels of certain substances in the blood which are sometimes raised with glucagonomas.

You may also have a blood test to check for a rare inherited condition called multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 (MEN1). This test is usually only requested by specialist doctors (genetic doctors).

Glucagonoma treatment

Glucagonoma is a type of neuroendocrine tumour (NET) that starts in the pancreas. The treatment you have depends on a number of things. This includes where the tumor is, its size and whether it has spread (the stage).

A team of doctors and other professionals discuss the best treatment and care for you. They are called a multidisciplinary team.

The treatment you have depends on:

- where the tumour is and its size

- whether it has spread

- your general health

- whether you have a rare inherited syndrome called multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 (MEN1)

Your doctor will discuss your treatment, its benefits and the possible side effects with you.

The first treatment you have is to control your symptoms. You then might have surgery to try to get rid of the glucagonoma tumor.

But surgery isn’t always possible. Some glucagonomas may have already started to spread when you are diagnosed. Or you may not be well enough to have it. You continue to have treatment to help your symptoms if surgery isn’t an option.

As per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the post-resection follow up includes history and physical examination, serum glucagon level, CT or MRI in the initial 3 to 12-month period. After 1 year, it is recommended to follow the same measures every 6 to 12 months up to a maximum of 10 years.

Treatments to help with symptoms

You have treatments to help with symptoms before you have surgery. You might also have these treatments if you can’t have surgery to remove the glucagonoma tumor or if it comes back after surgery.

These treatments can control the symptoms and help you feel better.

Drugs to help with symptoms

Symptoms are usually caused by the increase in the amount of glucagon in the body. So you might have drugs to reduce the amount of glucagon you make.

You might also have:

- Amino acids drip: People with glucagonomas often have low levels of amino acids. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. You usually have amino acids as a drip into a vein. You might have 1 or more drips. This might help with a common symptom of glucagonoma which is a skin rash called necrolytic migratory erythema.

- Drugs to control blood sugar levels: You have drugs to control the blood sugar level if it becomes too high. This is usually tablets, but you might also have insulin injections.

- Somatostatin analogues: Somatostatin is a protein made naturally in the body. It does several things including slowing down the production of hormones. Somatostatin analogues are man made versions of somatostatin. You may have somatostatin analogues to try to slow down the tumour and help with symptoms. They include:

- octreotide (Sandostatin)

- lanreotide (Somatuline)

Surgery to remove part of the glucagonoma tumor

Removing part of the glucagonoma tumor can reduce your symptoms. Your doctor will only suggest surgery if they think it’s possible to remove most of the glucagonoma tumor (at least 90%).

If the glucagonoma has spread to the liver, you might be able to have the liver glucagonoma tumor removed at the same time. Your surgeon may remove just the glucagonoma tumor, or part of the liver too.

Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency ablation uses heat made by radio waves to kill tumor cells. You might have this if the glucagonoma has spread to the liver.

Trans arterial embolization

You might have this treatment if the glucagonoma has spread to the liver.

Trans arterial embolization means having a substance such as a gel or tiny beads to block the blood supply to the liver glucagonoma. It is also called hepatic artery embolization.

You may also have a chemotherapy drug to the liver at the same time. This is called trans arterial chemoembolisation (TACE). But doctors don’t know for sure whether adding chemotherapy is better than having embolisation alone for glucagonomas that have spread to the liver.

Embolization and chemoembolization work in two ways:

- it reduces the blood supply to the tumor and so starves it of oxygen and the nutrients it needs to grow

- it gives high doses of chemotherapy to the tumor without affecting the rest of the body

Radiotherapy

You may have a type of internal radiotherapy called peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT). Internal radiotherapy means having radiotherapy from inside the body (as a drip into your bloodstream).

Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) uses a radioactive substance called lutetium-177 or yttrium-90 attached to a somatostatin analogue.

You may have peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) if:

- your glucagonoma has spread to other parts of the body

- you can’t have surgery

- your glucagonoma has receptors on the outside of them called somatostatin receptors (you have special scans called octreotide or gallium PET scans to check for this)

Targeted drugs

Cancer cells have changes in their genes (DNA) that make them different from normal cells. These changes mean that they behave differently. Targeted drugs work by ‘targeting’ the differences that a cancer cell has and destroying them.

You may have 2 types of targeted drugs called everolimus and sunitinib.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses anti cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy tumour cells. You may have chemotherapy if the glucagonoma has spread to the liver or to other parts of your body.

The most common chemotherapy drugs used are:

- streptozotocin or temozolomide

- fluorouracil or capecitabine

- doxorubicin

Interferon

Interferon is also called interferon alfa. You may have it if the glucagonoma has spread to other parts of the body. And other treatments have stopped working.

You may have interferon alone or with somatostatin analogues.

Clinical trials

Doctors are always trying to improve treatments and reduce the side effects. As part of your treatment, your doctor might ask you to take part in a clinical trial. This might be to test a new treatment or to look at different combinations of existing treatments.

Surgery

Surgery is the only treatment that can cure a glucagonoma. The type of surgery you have depends on the size of the tumour, where it is and whether it has spread to other parts of the body such as the liver.

Some of these are major operations and there are risks. But if the aim is to try to cure your glucagonoma, you might feel it is worth some risks. Talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of your surgery.

You usually have open surgery. This means your surgeon makes a large cut in your abdomen to remove the glucagonoma. They might also remove the nearby lymph nodes.

You might have surgery to remove:

- just the glucagonoma tumor (enucleation)

- the narrowest part of the pancreas and the body of the pancreas (distal pancreatectomy)

- the whole of the pancreas (total pancreatectomy)

- the widest part of the pancreas, the duodenum, gallbladder and part of the bile duct (pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy or PPPD for short)

- the widest part of the pancreas, duodenum, gallbladder, part of the bile duct and part of the stomach (Whipple’s operation)

If the glucagonoma has spread to the liver, you might be able to have the liver tumor removed at the same time you have the main surgery. Your surgeon may remove just the tumor or part of the liver too.

Management of progressive/Metastatic Disease

The most common site of glucagonoma metastasis is liver. Hepatic resection has been recommended in patients without widespread liver involvement, diffuse extrahepatic metastases, and decreased liver function 12. Resection has led to a decrease in glucagon levels and significant improvement of glucagonoma skin rash (necrolytic migratory erythema).

Hepatic arterial embolization with or without selective hepatic artery infusion of chemotherapy is a palliative method used in patients with symptomatic hepatic metastases and are not candidates for hepatic resection 13.

Radiofrequency ablation applies to smaller lesions (typically smaller than 3 cm) and is less invasive than hepatic resection or hepatic arterial embolization. It can be used as in conjunction with surgical resection, or as a primary treatment technique for the hepatic metastases 14.

Combination chemotherapy with streptozocin, 5-fluorouracil or Temozolomide containing regimens, often in combination with a somatostatin analog have been used in patients with large tumors and enlarging metastases. The use of systemic chemotherapy is limited to patients with advanced disease 15.

Molecular targeted agents such as sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and everolimus, a mTOR inhibitor are approved in the United States for treatment of advanced, well-differentiated, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors including glucagonomas 16.

Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), also known as radioisotope therapy, is a novel method being used for the management of neuroendocrine tumors. The high expression of somatostatin receptors in glucagonoma provides an opportunity for the use of PRRT 17.

Glucagonoma survival rate

Survival for glucagonomas depends on many factors. It depends on the stage and grade of the glucagonoma tumor when it was diagnosed. The stage describes the size of the tumour and whether it has spread. The grade means how abnormal the cells look under a microscope. Because glucagonomas are rare tumors, the survival of this disease is harder to estimate than for other, more common cancers. So you should only use these statistics as a guide. These are general statistics based on small groups of people. Remember, they can’t tell you what will happen in your individual case. Your doctor can give you more information about your own outlook (prognosis).

Approximately 60% of glucagonoma are cancerous. It is common for this cancer to spread to the liver. Only about 20% of people can be cured with surgery.

About 64 out of every 100 people (64%) with glucagonoma that has not spread to other parts of the body survive for 10 years or more.

If glucagonoma is only in the pancreas and surgery to remove it is successful, people have a 5-year survival rate of 85%.

Almost 52 out of every 100 people (52%) with glucagonoma that has spread to other parts of the body survive for 10 years or more.

References- Wynick D, Williams SJ, Bloom SR. Symptomatic secondary hormone syndromes in patients with established malignant pancreatic endocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 1988;319:605-7.

- Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Brandi ML, de Herder WW, Kaltsas G, Komminoth P, Scoazec JY, Salazar R, Sauvanet A, Kianmanesh R., Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: functional pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95(2):98-119.

- Sandhu S, Jialal I. Glucagonoma Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519500

- Wermers RA, Fatourechi V, Wynne AG, Kvols LK, Lloyd RV. The glucagonoma syndrome. Clinical and pathologic features in 21 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996 Mar;75(2):53-63.

- Altimari AF, Bhoopalam N, O’Dorisio T, Lange CL, Sandberg L, Prinz RA. Use of somatostatin analogue (SMS 201-995) in the glucagonoma syndrome. Surgery 1986;100:989-96.

- Mittendorf, Elizabeth & Shifrin, Alexander & B Inabnet, William & Libutti, Steven & R McHenry, Christopher & Demeure, Michael. (2006). Islet Cell Tumors. Current problems in surgery. 43. 685-765. 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2006.07.003

- Ito T, Igarashi H, Jensen RT. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: clinical features, diagnosis and medical treatment: advances. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012 Dec;26(6):737-53.

- Prinz RA, Sagimoto J, Lorincz A, et al. Glucagonoma. In: Howard JM, Jordan GL Jr, Reber HA, editors. Surgical Diseases of the Pancreas. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1987; pp 848-57.

- Prinz RA, Dorsch TR, Lawrence AM, et al. Clinical aspects of glucagon producing islet cell tumors. Am J Gastroenterol 1981;76:125-31.

- Bordi C, Yu JY, Girolami A, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of factor X-like antigen in pancreatic islets and their tumours. Virchows Arch A 1990;416:397-402.

- Edney JA, Hofmann S, Thompson JS, Kessinger A. Glucagonoma syndrome is an underdiagnosed clinical entity. Am J Surg 1990;160:625-9.

- McEntee GP, Nagorney DM, Kvols LK, Moertel CG, Grant CS. Cytoreductive hepatic surgery for neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 1990 Dec;108(6):1091-6.

- Kennedy AS. Hepatic-directed Therapies in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2016 Feb;30(1):193-207.

- King J, Quinn R, Glenn DM, Janssen J, Tong D, Liaw W, Morris DL. Radioembolization with selective internal radiation microspheres for neuroendocrine liver metastases. Cancer. 2008 Sep 01;113(5):921-9.

- Pavel M, Valle JW, Eriksson B, Rinke A, Caplin M, Chen J, Costa F, Falkerby J, Fazio N, Gorbounova V, de Herder W, Kulke M, Lombard-Bohas C, O’Connor J, Sorbye H, Garcia-Carbonero R., Antibes Consensus Conference Participants. Antibes Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Systemic Therapy – Biotherapy and Novel Targeted Agents. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105(3):266-280.

- Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, Bohas CL, Wolin EM, Van Cutsem E, Hobday TJ, Okusaka T, Capdevila J, de Vries EG, Tomassetti P, Pavel ME, Hoosen S, Haas T, Lincy J, Lebwohl D, Öberg K., RAD001 in Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors, Third Trial (RADIANT-3) Study Group. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011 Feb 10;364(6):514-23.

- Kwekkeboom DJ, Bakker WH, Kam BL, Teunissen JJ, Kooij PP, de Herder WW, Feelders RA, van Eijck CH, de Jong M, Srinivasan A, Erion JL, Krenning EP. Treatment of patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) tumours with the novel radiolabelled somatostatin analogue [177Lu-DOTA(0),Tyr3]octreotate. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2003 Mar;30(3):417-22.