Heel pad syndrome

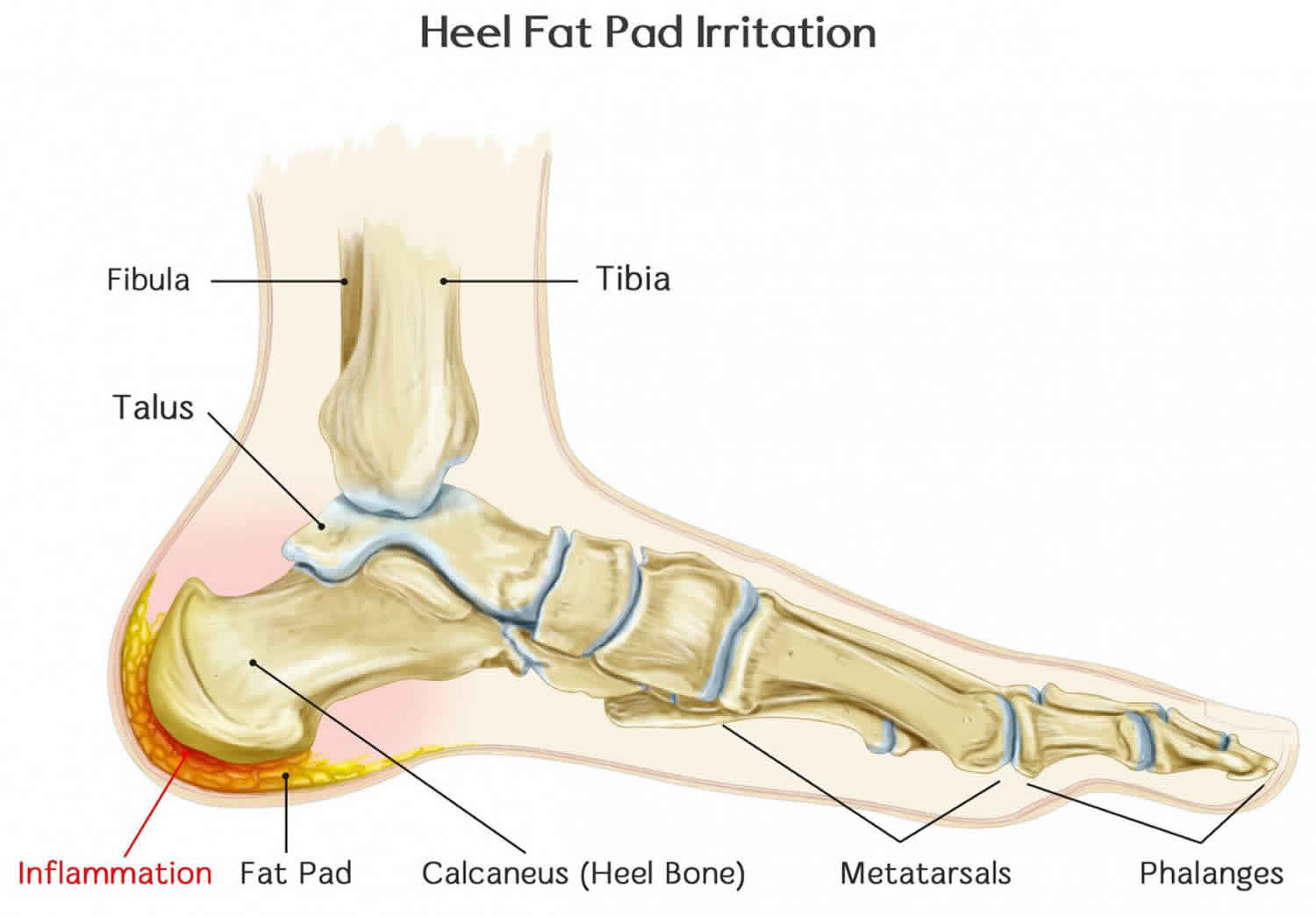

The heel fat pad also called corpus adiposum is composed of closely packed fat chambers surrounded by tough circular or cone-shaped collagenous septa and elastin fibers 1. Heel fat pad main purpose is to function as a shock absorber and protect the heel bone (calcaneus) and the foot arch from impact injury. Ideally, the fat pad of the heel is thick and dense, making it the perfect cushion for the bones of your heel and foot. Over a period of time, the heel fat pad can atrophy (shrink) due to micro-trauma and repeated corticosteroid injections, leading to a decrease in the shock absorbing properties and development of heel pain. Heel fat pad is less elastic in elderly and diabetic patients, which leads to inflammation and edema. Diabetic plantar tissue is stiffer than healthy tissue and has a lower capacity to withstand compressive and shear stresses. This type of heel paid pain is known as heel pad syndrome. Heel fat pad syndrome develops when the entire fat pad, or smaller sections of the heel fat pad, become thin and damaged.

Pain from heel pad syndrome also known as heel fat pad syndrome, is often erroneously attributed to plantar fasciitis. Patients with heel pad syndrome present with deep, bruise-like pain, usually in the middle of the heel, that can be reproduced with firm palpation. Walking barefoot or on hard surfaces exacerbates the pain. Heel pad syndrome is usually caused by inflammation, but damage to or atrophy of the heel pad can also elicit pain. Decreased heel pad elasticity with aging and increasing body weight can also contribute to heel fat pad syndrome 2.

The health of the foot arch and gait are the two biggest factors in contributing to heel pad pain. During walking, the feet absorb the impact of approximately two times the weight of the person’s body. When running or jumping, this force is even greater. The way the heel strikes the ground surface as a person moves will generally determine where the heel pad will wear down most quickly. Likewise, the arch of the foot functions to prop the foot up correctly, and if that arch is strained or injured (such as what happens with plantar fasciitis), this puts extra pressure on the heel pad.

Frequently misdiagnosed as plantar fasciitis, heel pad syndrome is characterized by deep, non-radiating pain involving the weight-bearing portion of the calcaneus (see Figure 2). Symptoms worsen with walking barefoot or on hard surfaces and are relieved in the absence of heel pressure. Typically, there is tenderness over the plantar aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity. Swelling is variably present and, unlike plantar fasciitis, pain does not occur with passive motion of the ankle or toes.

Treatment is aimed at decreasing pain with rest, ice, and anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications (NSAIDs). Adequate heel padding, heel cups, proper footwear, and taping can also be used. Corticosteroid injections are contraindicated as they can cause atrophy of the plantar fat 3. Surgery cannot restore the normal architecture of the heel pad. In addition, the plantar skin is prone to wound-healing problems.

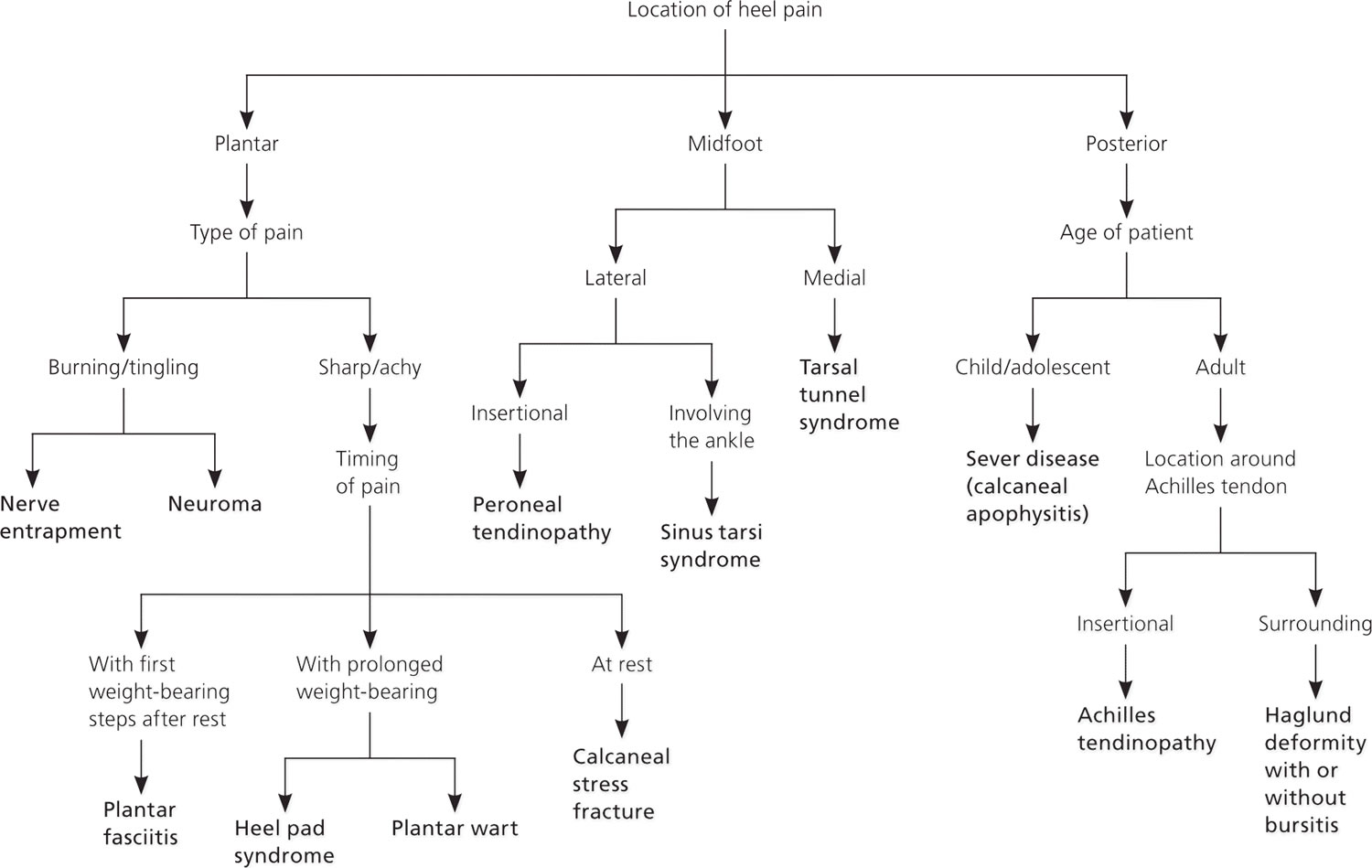

Figure 1. Causes of heel pain

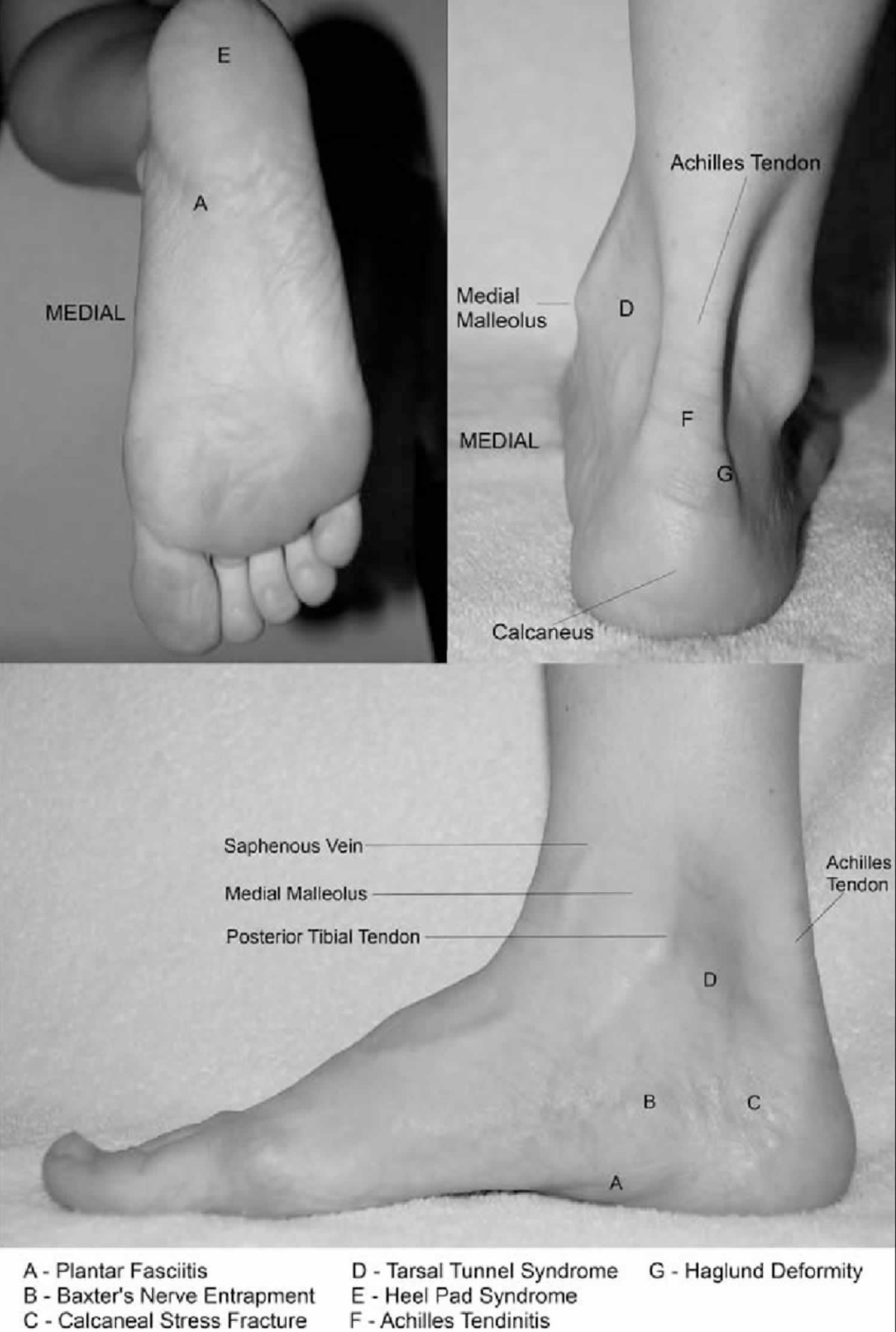

[Source 4 ]Figure 2. Heel pain anatomy

[Source 5 ]Heel Pad Syndrome versus Plantar Fasciitis

Heel pad syndrome

Characteristic signs of heel pad syndrome include:

- Pain feels like a bruise and is close to the centre of the heel

- Pain is worse when walking on hard surfaces such as concrete or tiles

- Pain is worse when walking barefoot

- Pain can be recreated by pressing a finger into the middle of the heel.

Heel pad pain is caused by the wearing down or damage to the heel fat pad.

Plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis is an inflammation of the band of tissue (the plantar fascia) that extends from the heel to the toes. In plantar fasciitis, the fascia first becomes irritated and then inflamed, resulting in heel pain. Plantar fasciitis is sometimes also called heel spur syndrome when a spur is present.

The most common cause of plantar fasciitis relates to faulty structure of the foot. For example, people who have problems with their arches, either overly flat feet or high-arched feet, are more prone to developing plantar fasciitis.

Wearing nonsupportive footwear on hard, flat surfaces puts abnormal strain on the plantar fascia and can also lead to plantar fasciitis. This is particularly evident when one’s job requires long hours on the feet. Obesity and overuse may also contribute to plantar fasciitis.

The symptoms of plantar fasciitis are:

- Pain on the bottom of the heel

- Tenderness on medial calcaneal tuberosity and along plantar fascia

- Pain with first steps in the morning or after long periods of rest

- Pain that increases over a period of months

- Pain generally improves with rest and appropriate stretching.

- Swelling on the bottom of the heel

People with plantar fasciitis often describe the pain as worse when they get up in the morning or after they have been sitting for long periods of time. After a few minutes of walking, the pain decreases because walking stretches the fascia. For some people, the pain subsides but returns after spending long periods of time on their feet.

Treatment of plantar fasciitis begins with first-line strategies, which you can begin at home:

- Stretching exercises. Exercises that stretch out the calf muscles help ease pain and assist with recovery.

- Avoid going barefoot. When you walk without shoes, you put undue strain and stress on your plantar fascia.

- Ice. Putting an ice pack on your heel for 20 minutes several times a day helps reduce inflammation. Place a thin towel between the ice and your heel; do not apply ice directly to the skin.

- Limit activities. Cut down on extended physical activities to give your heel a rest.

- Shoe modifications. Wearing supportive shoes that have good arch support and a slightly raised heel reduces stress on the plantar fascia.

- Medications. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, may be recommended to reduce pain and inflammation.

If you still have pain after several weeks, see your foot and ankle surgeon, who may add one or more of these treatment approaches:

- Padding, taping and strapping. Placing pads in the shoe softens the impact of walking. Taping and strapping help support the foot and reduce strain on the fascia.

- Orthotic devices. Custom orthotic devices that fit into your shoe help correct the underlying structural abnormalities causing the plantar fasciitis.

- Injection therapy. In some cases, corticosteroid injections are used to help reduce the inflammation and relieve pain.

- Removable walking cast. A removable walking cast may be used to keep your foot immobile for a few weeks to allow it to rest and heal.

- Night splint. Wearing a night splint allows you to maintain an extended stretch of the plantar fascia while sleeping. This may help reduce the morning pain experienced by some patients.

- Physical therapy. Exercises and other physical therapy measures may be used to help provide relief.

Heel pad syndrome causes

Heel pad syndrome, and consequently heel pad pain, develops as a result of overuse, injury, micro-trauma or repeated corticosteroid injections. Some of the most common causes are:

Inflammation of the fat pad

When the heel pad is placed under repeated forceful activity for prolonged periods of time, inflammation can occur. Commonly, this occurs with activities such as gymnastics, basketball or volleyball, where lots of jumping is required.

Thinning or displacement of the fat pad

The heel fat pad may become displaced or thinned. This occurs more commonly in the elderly, as the aging process leads to some natural loss in elasticity. The heel pad pain feels like bruising, and is a result of the exposed heel bone bearing force.

Overweight and obesity

Carrying excess body weight puts undue pressure and extra stress on the heel fat pad, which may lead to it deteriorating more quickly 6..

Walking on hard surfaces (force)

When walking or running barefoot, the force that has to be absorbed by the heel is most extreme. This is especially true when walking or running on hard surfaces. This type of pressure placed on the heel can quickly lead to thinning and straining of the heel fat pad, or bruising of the heel bone.

Plantar fasciitis

When the plantar fascia ligament becomes inflamed or even begins to degenerate, it has a reduced ability to absorb and distribute impact in the foot from walking or running. In this case, the heel fat pad may become strained, worn or injured much more quickly than it would otherwise.

Improper gait (manner of walking)

Having overpronated or underpronated feet (feet which lean inwards or outwards, respectively) can cause heel pad pain, because with walking or running, the heel strikes the ground in a suboptimal way. This can lead to the heel fat pad thinning or becoming inflamed in the particular areas where it strikes the ground most forcefully.

Fat pad atrophy due to medical conditions

There are some medical conditions that may contribute to the shrinking of the heel fat paid, causing heel pad pain. These include type 2 diabetes, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Heel spurs

Heel spurs can contribute to heel pad pain by physically digging into the heel fat pad.

Heel pad syndrome symptoms

While both plantar fasciitis and heel pad syndrome cause pain in the heels, the hallmark symptoms of heel fat pad syndrome are a little different:

- Pain that is a little duller (more like a bruise), and felt closer to the middle of your heel

- Pain that you can recreate by pressing your finger into the middle of your heel pad

- Pain that is made worse when you walk on hard surfaces such as concrete or tiles.

Heel pad syndrome diagnosis

The cause of heel fat pad syndrome is diagnosed using a number of tests, including:

- Medical history

- Physical examination, including examination of joints and muscles of the foot and leg

- X-rays.

During your consultation for your heel pad pain, your sports podiatrist will conduct a thorough physical examination. They will also collect a comprehensive exercise and physical activity history from you. Your sports podiatrist may order a medical imaging test, such as an x-ray or ultrasound to assess the thickness and elasticity of the heel fat pad. A typical healthy heel pad is usually between 1-2cm thick. To assess the heel’s elasticity, your podiatrist may compare the heel’s thickness when standing (bearing the weight of the foot) compared to when it is not. The heel fat pad should be pliable and should adequately compress when you stand; if it is stiff and does not, it may indicate low elasticity.

Heel pad syndrome treatment

The aim of treating heel pad pain is to reduce the pain and inflammation itself, as unfortunately there is no cure for heel fat pad syndrome. Your sports podiatrist may suggest one or more of the following treatments:

- Rest: if you can, stay off your feet completely, or avoid doing activities cause heel pad pain or make it worse

- NSAIDs: over-the-counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen can be effective in reducing inflammation and reducing pain

- Ice: applying a covered ice pack to the sore heel for up 20 minutes at a time, at regular intervals throughout the day or immediately after activities that make the heel pad pain worse, can reduce inflammation and relieve pain

- Taping: sports tape may be used to hold the heel pad in place and provide more ‘cushioning’ or protection for the heel bone

- Heel pads, cups or orthoses: there are different types of implements that may be recommended by your sports podiatrist to either hold the fat pad in place, provide extra cushioning (usually foam or gel) for the heel, or to stabilize the bones of the foot and contain the fat pad

- Stretching and strengthening: your sports podiatrist may recommend particular exercises that are appropriate for your condition to improve flexibility and strength in areas where it is required.

- Allam AE, Chang KV. Plantar Heel Pain. [Updated 2019 May 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499868

- Prichasuk S. The heel pad in plantar heel pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(1):140–142.

- Brinks A, Koes BW, Volkers AC, Verhaar JA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Adverse effects of extra-articular corticosteroid injections: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:206.

- Diagnosis of Heel Pain. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Oct 15;84(8):909-916. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/1015/p909.html

- Sawyer, Gregory & Lareau, Craig & Mukand, Jon. (2012). Diagnosis and management of heel and plantar foot pain. Medicine and health, Rhode Island. 95. 125-8.

- Prichasuk S. The heel pad in plantar heel pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. Jan 1994;76(1):140-142.