What is introitus

Introitus is the opening of the vagina. The vaginal opening is called the introitus of the vagina.

Vaginal introitus

A woman may complain to her doctor that her vaginal introitus (opening) feels or appears enlarged. This can be the result of pelvic organ prolapse or a damaged perineal body 1. This problem is not life-threatening, but a woman may complain of a bulge coming out her vagina, sexual dysfunction, or defecatory dysfunction. The urogynecologic term for this is an enlarged “genital hiatus”, although other doctors may use the terms “relaxed vaginal outlet” or “enlarged vaginal introitus.” None of these terms are an actual diagnosis, but rather a physical exam finding of which a patient may or may not be symptomatic 1.

There is no formal diagnosis for an enlarged vaginal introitus, as patients usually present with a specific complaint that is resultant from her pelvic organ support defects 1. An enlarged vaginal introitus can be related to stretching of the introitus from prolapse of the vagina (cystocele or rectocele), from weakening of the distal rectovaginal septum, or from disruption of the perineal body (example: perineal lacerations at vaginal delivery) 1.

Gynecologists can determine from a pelvic exam which of these anatomic areas are disrupted. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system, a standardized method with nine values, describes site-specific prolapse. One of these values, the “genital hiatus,” measures from the mid-urethra to the posterior midline hymen 2. There is no absolute “normal” for the length of a patient’s vaginal introitus, but 2 to 6cm is most commonly observed in asymptomatic patients in the author’s experience. Patients with an enlarged vaginal introitus are not always symptomatic.

In the United States, the exact incidence of enlarged vaginal introitus is unknown because not all patients are symptomatic and this finding alone is not a medical diagnosis. Prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse, however, has been studied and an enlarged vaginal introitus may be seen in these women. In patients age 40 and older, the rate of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse is estimated to be 3.8% 3. The lifetime risk of needing a surgery for pelvic organ prolapse has been reported as 12.6% 4.

Figure 1. Parous vaginal introitus

Footnote: Multiparous patient with an approximately 3cm vaginal introitus.

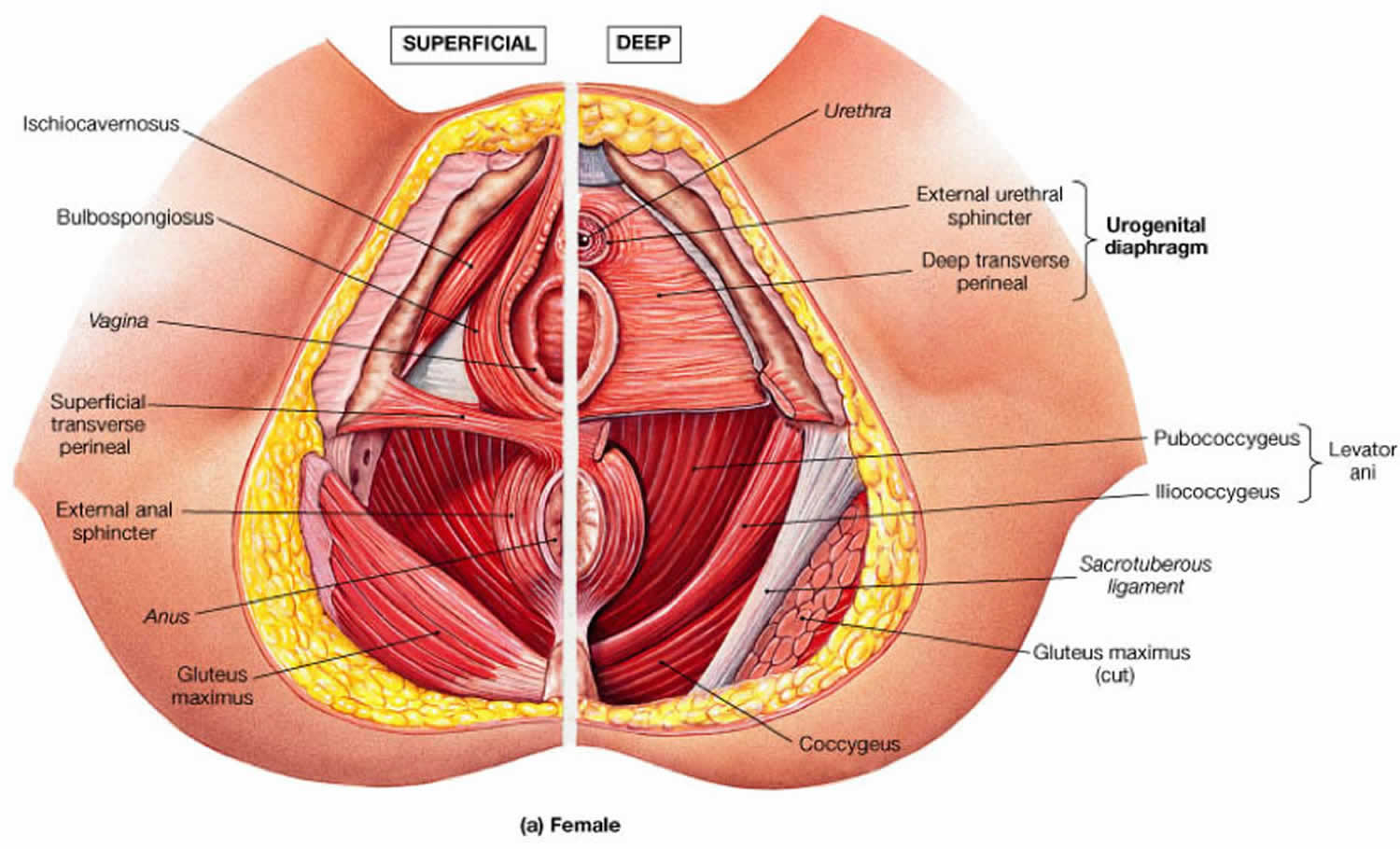

Figure 2. Muscles of the pelvic floor

Gaping vaginal introitus causes

The main support for the pelvic organs is provided by a group of muscles collectively called the levator ani. An intact pelvic floor allows the pelvic and abdominal viscera to “rest” on the levator ani, significantly reducing the tension on the supporting fascia and ligaments. Externally, the perineal body is the conversion of the bulbocavernosus, transverse perineal, and external anal sphincter muscles (see Figure 2).

Pelvic floor disorders are rarely caused by a single event. With stretching of the muscles and endopelvic fascia (example: pregnancy, years of straining, advancing age) or with trauma to the tissues with a perineal laceration at time of childbirth, neuromuscular changes occur that result in the pelvic organs no longer having the same support to remain suspended in the pelvis. Disruption of the perineal body may allow for descent of the posterior vaginal wall through the introitus. Clinical measurements of the vaginal introitus correlate with severity of pelvic organ prolapse 5.

Delancey describes a conceptual model, the Lifespan Model, which suggests that pelvic floor disorders are the result of different combinations of biologic and lifestyle factors 6. The first phase consists of “predisposing factors”, such as genetics, nutrition, and toilet training. Although a specific genetic predisposition has not been identified, collagen type 3 alpha 1 has been found to be associated with pelvic organ prolapse 7. The second phase includes “inciting factors”, such as childbirth and obstetric interventions at time of delivery. The third and final phase of the model consists of “intervening factors” which include obesity, age, high impact aerobics, heavy lifting or straining, among other repetitive traumas caused to the pelvic floor. Collectively over a lifetime, the pelvic floor experiences dysfunction that may lead to symptomatic pelvic floor disorders 8.

Gaping vaginal introitus symptoms

Symptoms of patients with an enlarged vaginal introitus may vary from completely asymptomatic to bothersome daily complaints. History taking and a careful pelvic exam are essential for proper management of these patients.

Those with an enlarged vaginal introitus who also have a rectocele may complain of a bulge coming from her vagina or defecatory dysfunction, including constipation or even the need to splint a finger on the perineum or in the vagina to evacuate the rectum.

Some women complain of sexual dysfunction. A patient may state she no longer feels the same amount of sexual pleasure, attributing this to her “relaxed” vaginal opening. This complaint alone is an uncommon reason to perform a revision perineorrhaphy, which would reapproximate the perineal body.

Gaping vaginal introitus treatment

Medical therapy

Conservative management for patients who complain about an enlarged vaginal introitus includes pelvic floor physical therapy. This is a non-invasive treatment method in which specially trained physical therapists perform internal and external therapy aimed at strengthening and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles. Pelvic floor physical therapy is a structured and comprehensive program that sometimes includes biofeedback therapy, which is visual confirmation the patient is contracting her muscles appropriately. An individualized home exercise program is also prescribed by the patient’s therapist. Coordinating the pelvic floor muscles along with behavioral modification education can lead to improvement and even resolution of many pelvic floor disorders. 9.

Pessary use is another conservative treatment modality that would be appropriate if the enlarged vaginal introitus is due to pelvic organ prolapse. The practitioner may choose from many shapes and sizes of pessaries depending upon the patient’s symptoms and type of prolapse. Patients with an enlarged vaginal introitus may not be able to retain pessaries as well, however, depending on her genital hiatus to total vaginal length ratio 10. A pessary can be used concurrently with pelvic floor physical therapy.

Surgical therapy

The surgical procedure to repair an enlarged vaginal introitus is called a perineorrhaphy, which may be performed concomitantly with surgery to correct pelvic organ prolapse. There are variations in technique and suture material, but the surgeon is essentially reattaching rectovaginal fascia to the perineal body and reapproximating the perineal body muscle support. By re-creating the perineal body, the enlarged vaginal introitus becomes smaller 11. However, surgical repair is not necessary unless the patient has bothersome symptoms and has failed conservative therapy. The potential for postoperative dyspareunia is rarely justified to repair an asymptomatic rectocele, perineocele or defective perineal body support.

A survey of almost 200 gynecologists indicated that the decision to perform a perineorrhaphy, which reapproximates the perineal body and thus decreases the size of the vaginal introitus, is made with the patient in the office in about 65% of cases; other times it is made in the operating room either after an exam under anesthesia or after a concomitant pelvic organ prolapse repair. Size of the vaginal introitus and concomitant prolapse repairs are the most common reason to perform the procedure. Dyspareunia, sexual dysfunction, and cosmesis are less important to surgeons when making the decision of whether or not to perform a perineorrhaphy 11.

References- Relaxed Vaginal Outlet. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/268428-overview

- Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Jul. 175 (1):10-7.

- Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008 Sep 17. 300 (11):1311-6.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun. 123 (6):1201-6.

- Ghetti C, Gregory WT, Edwards SR, Otto LN, Clark AL. Severity of pelvic organ prolapse associated with measurements of pelvic floor function. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005 Nov-Dec. 16 (6):432-6.

- Delancey JO, Kane Low L, Miller JM, Patel DA, Tumbarello JA. Graphic integration of causal factors of pelvic floor disorders: an integrated life span model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Dec. 199 (6):610.e1-5.

- Ward RM, Velez Edwards DR, Edwards T, Giri A, Jerome RN, Wu JM. Genetic epidemiology of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Oct. 211 (4):326-35.

- Hallock JL, Handa VL. The Epidemiology of Pelvic Floor Disorders and Childbirth: An Update. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016 Mar. 43 (1):1-13.

- Lamin E, Parrillo LM, Newman DK, Smith AL. Pelvic Floor Muscle Training: Underutilization in the USA. Curr Urol Rep. 2016 Feb. 17 (2):10.

- Geoffrion R, Zhang T, Lee T, Cundiff GW. Clinical characteristics associated with unsuccessful pessary fitting outcomes. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013 Nov-Dec. 19 (6):339-45.

- Kanter G, Jeppson PC, McGuire BL, Rogers RG. Perineorrhaphy: commonly performed yet poorly understood. A survey of surgeons. Int Urogynecol J. 2015 Dec. 26 (12):1797-801.