Laryngotracheobronchitis

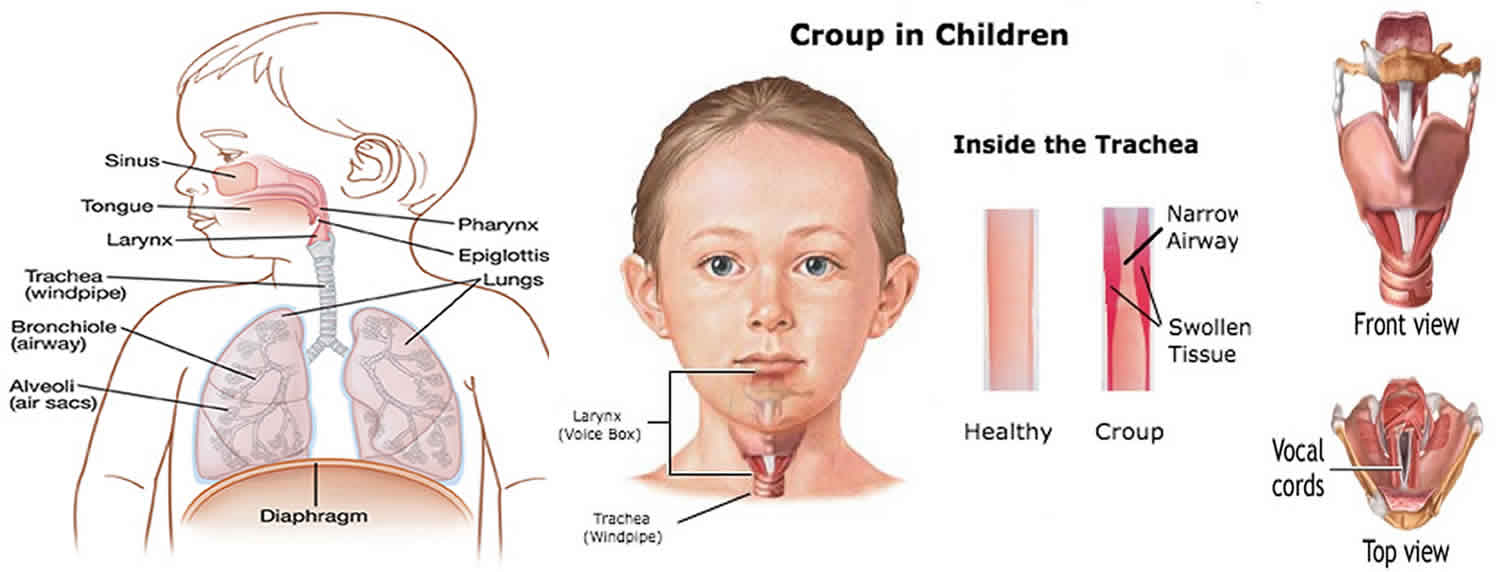

Laryngotracheobronchitis also known as croup, is a common inflammation of the upper airway, the vocal cords (larynx or voice box) and the windpipe (trachea) usually triggered by a virus in children between the ages of 3 months to 6 years. Although uncommon after age 6 years, croup may be diagnosed in the preteen and adolescent years and, rarely in adults 1. Croup generally affects the larynx and trachea, although this illness may also extend to the airways to the lungs (the bronchi). This swelling makes the airway narrower, so it is harder to breathe. Croup causes difficulty breathing, a seal barking cough, and a hoarse voice. The cause is usually a virus, often parainfluenza virus. Other causes include allergies and reflux. Laryngotracheobronchitis (croup), recognized by physicians for centuries, derives its name from an Anglo-Saxon word, kropan, or from an old Scottish word, roup, meaning to cry out in a hoarse voice.

When a child with croup has a cough that forces air through the narrowed airway passages, the swollen vocal cords produce a noise similar to a seal barking. Likewise, taking a breath in often produces a high-pitched whistling sound known as stridor. Stridor generally indicates some obstruction or narrowing of the windpipe. Stridor is also occasionally caused by a condition called epiglottitis. It might also be caused by an inhaled foreign body.

Laryngotracheobronchitis (croup) is the most common cause for hoarseness, cough, and onset of acute stridor often worse at night in febrile children. Symptoms of stuffy nose may be absent, mild, or marked. The vast majority of children with croup recover without consequences or complications; however, it can be life-threatening in young infants.

Croup often starts out like a cold. But then the vocal cords and windpipe become swollen, causing the hoarseness and the cough. There may also be a fever and high-pitched noisy sounds when breathing. The symptoms are usually worse at night, and last for about three to five days.

Children with croup should have minimal examination so as not to upset the child further. Throat examination is rarely required.

Most cases of viral croup are mild and can be treated at home. You can manage the symptoms in exactly the same way as for a cold. It’s important to try and keep your child calm, because your child can have more trouble breathing if they are upset, frightened or stressed. Croup is most commonly caused by a virus, so antibiotics won’t work. Antibiotics treat only bacterial infections. Steam therapy, including the use of vaporisors, is no longer recommended.

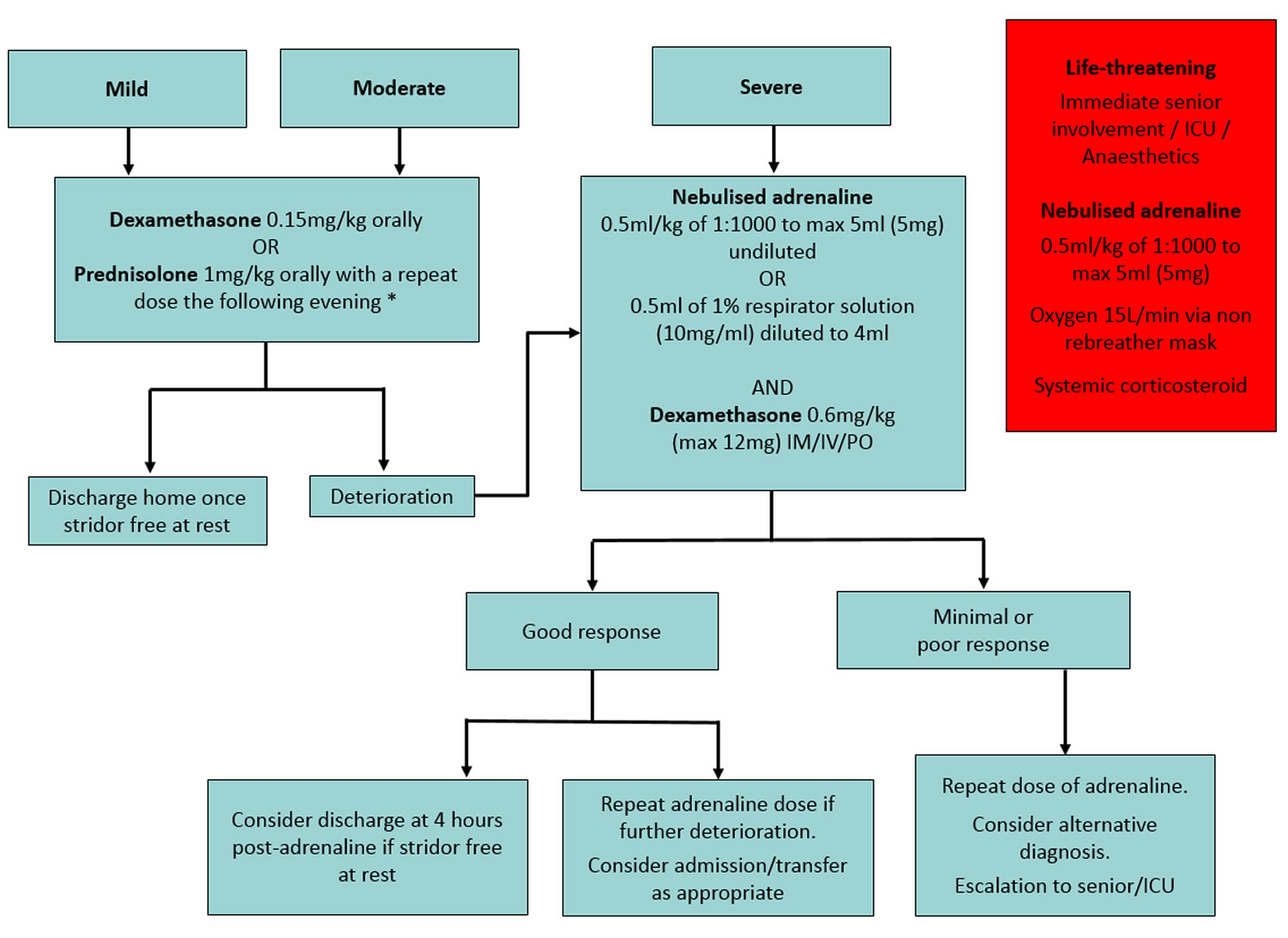

Rarely, croup can become serious and interfere with your child’s breathing. If you are worried about your child’s breathing, see your health care provider right away. Your doctor may prescribe medicines that can help reduce the inflammation and swelling such as oral corticosteroid medicine.

A few children with croup need to go to hospital for observation, to ensure that their windpipes don’t get blocked. While in hospital, your child might initially receive nebulized adrenaline (adrenalin given via a face mask) to relieve the spasm and swelling until the steroids work.

Croup generally resolves after 48 hours of onset of symptoms, however it can last up to a week. In general 5% of children with croup are hospitalized, this rate of hospitalization is increased in children who develop complications of the disease.

Laryngotracheobronchitis key points

- Minimize distress to the child as this can worsen upper airway obstruction.

- Consider early transfer and involvement of senior staff if concerns regarding worsening upper airway obstruction.

- For severe and life-threatening croup use nebulized adrenaline.

- Less severe cases can be managed with corticosteroids alone.

Approximately 5 percent of children seen in the emergency department for croup require hospitalization.

You should get medical help immediately if you notice any of the following:

- Your child makes noisy, high-pitched breathing sounds (stridor) both when inhaling and exhaling

- Your child begins drooling or has difficulty swallowing

- Your child seems anxious and agitated or fatigued and listless

- Your child has difficulty breathing or breathes at a faster rate than usual

- Your child has noisy breathing when at rest

- Your child becomes floppy

- You notice your child’s breastbone being sucked right back

- Your child becomes restless, distressed, irritable and/or delirious

- Your child struggles to breathe

- Your child develops blue or grayish skin around the nose, mouth or fingernails (cyanosis), which usually happens after a coughing spell

- You’re worried or concerned for any reason

You should call an ambulance (call your local emergency number) immediately if:

- your child looks very sick and becomes pale and drowsy.

- your child’s lips are blue in color.

Croup is most often mild, but it can still be dangerous. It most often goes away in 3 to 7 days.

The tissue that covers the trachea (windpipe) is called the epiglottis. If the epiglottis becomes infected, the entire windpipe can swell shut. This is a life-threatening condition.

If an airway blockage is not treated promptly, the child can have severe trouble breathing or breathing may stop completely.

Figure 1. Larynx and pharynx anatomy

Is croup contagious?

Yes, croup is an inflammation of the windpipe (trachea), the airways to the lungs (the bronchi) and the vocal cords (larynx or voice box) that is usually caused by viruses especially parainfluenza virus. However, any virus, bacteria and irritation to the trachea, bronchi and larynx can cause croup.

Can adults get croup?

Yes, but very rarely. For example inflammation of the windpipe (trachea), the airways to the lungs (the bronchi) and the vocal cords (larynx or voice box) can be caused by acid reflux disease or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Laryngotracheobronchitis causes

Laryngotracheobronchitis (croup) is most often caused by viruses such as parainfluenza viruses (types 1, 2, 3), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), measles, adenovirus, and influenza. It tends to appear in children between 3 months and 6 years old, but it can happen at any age. Some children are more likely to get croup and may get it several times. It is most common between October and March, but can occur at any time of the year.

More severe cases of croup may be caused by bacteria. This condition is called bacterial tracheitis. Prior to 1970, diphtheria, also known as membranous croup, was a common cause of croup-like symptoms. Vaccine coverage for diphtheria has eliminated this infection with no case reported in the United States for decades.

Laryngotracheobronchitis (croup) may also be caused by:

- Allergies

- Breathing in something that irritates your airway

- Acid reflux

Viruses causing acute infectious croup are spread through either direct inhalation from a cough and/or sneeze, or by contamination of hands from contact with fomites with subsequent touching the mucosa of the eyes, nose, and/or mouth. The most common viral causes are parainfluenza viruses (types 1, 2, 3). The type of parainfluenza (1, 2, and 3) virus causing croup outbreaks varies each year. Parainfluenza viruses (types 1, 2, 3) are responsible for about 80% of croup cases, with parainfluenza types 1 and 2, accounting for nearly 66% of cases. Type 3 parainfluenza virus causes bronchiolitis and pneumonia in young infants and children. Type 4 parainfluenza virus, with subtypes 4A and 4B, is not as well understood and tends to be associated with a milder clinical illness.

The primary ports of viral entry are the nose and nasopharynx. The infection spreads and eventually involves the larynx and trachea. The lower respiratory tract may also be affected, as in acute laryngotracheobronchitis. Some practitioners feel that with lower airway involvement, further diagnostic evaluation is warranted to address concern for a secondary bacterial infection.

Inflammation and edema of the subglottic larynx and trachea, especially near the cricoid cartilage, are most clinically significant. Histologically, the involved area is edematous, with cellular infiltration located in the lamina propria, submucosa, and adventitia. The infiltrate contains lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils and plasma cells. Parainfluenza virus activates chloride secretion and inhibits sodium absorption across the tracheal epithelium, contributing to airway edema. The anatomical area impacted is the narrowest part of the pediatric airway; accordingly, swelling can significantly reduce the diameter, limiting airflow. This narrowing results in the seal-like barky cough, turbulent airflow, stridor, and chest wall retractions. Endothelial damage and loss of ciliary function also occur. A mucoid or fibrinous exudate partially occludes the lumen of the trachea. Decreased mobility of the vocal cords due to edema leads to the associated hoarseness.

In severe disease, fibrinous exudates and pseudomembranes may develop, causing even greater airway obstruction. Hypoxemia may occur from progressive luminal narrowing and impaired alveolar ventilation and ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

Spasmodic croup (laryngismus stridulus) is a noninfectious variant of the disorder, with a clinical presentation similar to that of the acute disease but typically without fever and with less coryza. This type of croup always occurs at night and has the hallmark of reoccurrence in children; hence it has also been called “recurrent croup.” In spasmodic croup, subglottic edema occurs without the inflammation typical in acute viral disease. Although viral illnesses may trigger this variant, the reaction may be of allergic etiology rather than a direct result of an infectious process.

Risk factors for croup

Most at risk of getting croup are children between 6 months and 3 years of age. The peak incidence of the condition is around 24 months of age.

Risk factors for developing severe croup include the following:

- Seasonal variation; with the highest incidence in late autumn, however the condition can occur all year round.

- Viral infection; 75% of all cases are the result of infection with parainfluenza virus, most commonly type 1. Other causes include respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), metapneumovirus, influenza A and B, adenovirus, and mycoplasma.

- Prematurity

- Young age: uncommon < 6 months old, rare < 3 months of age. Consider alternative diagnosis and causes of upper airway obstruction

- Asthma, specifically for spasmodic croup

- Pre-existing narrowing of upper airways

- Previous admissions with severe croup

Laryngotracheobronchitis prevention

To prevent croup, take the same steps you use to prevent colds and flu. Frequent hand-washing is the most important. Also keep your child away from anyone who’s sick, and encourage your child to cough or sneeze into his or her elbow.

To stave off more-serious infections, keep your child’s vaccinations current. The diphtheria and Haemophilus influenza type b vaccines offer protection from some of the rarest — but most dangerous — upper airway infections. There isn’t a vaccine yet that protects against parainfluenza viruses.

There are a few things you can do to try to limit the spread of infection:

- wash your hands regularly

- always cough and sneeze into a tissue, before throwing it away immediately

- clean surfaces regularly to keep them free of germs

- avoid sharing unwashed cups, plates, cutlery and other kitchen utensils.

Laryngotracheobronchitis signs and symptoms

The main symptom of croup is a cough that sounds like a seal barking.

Most children will have mild cold symptoms for several days before the barking cough becomes evident. As the cough gets more frequent, the child may have trouble breathing or stridor (a harsh, crowing noise made when breathing in).

Croup is typically much worse at night. It often lasts 5 or 6 nights. The first night or two are most often the worst. Rarely, croup can last for weeks. Talk to your child’s health care provider if croup lasts longer than a week or comes back often.

Laryngotracheobronchitis signs and symptoms include:

- Barking cough

- Inspiratory stridor

- Hoarse voice

- May have associated widespread wheeze

- Increased work of breathing

- May have fever, but no signs of toxicity

Because children have small airways, they are most susceptible to having more marked symptoms with croup, particularly children younger than 3 years old.

In most children, the symptoms improve over three to five days then disappear.

Croup is often only a mild illness, but it can become serious quickly.

Rarely, in severe forms of the disease, features of respiratory distress can occur:

- Soft tissue recession (indrawing of the skin due to increased effort of breathing)

- Irritability

- Lethargy

- Cyanosis (blue discoloration of the skin due to poor oxygenation of blood)

Because of the increased effort of breathing children may become dehydrated, this may be seen as:

- Sunken eyes

- Dry mucous membranes such as dry mouth, dry eyes (i.e. the child will cry with less tears)

- Reduced urine output

- Reduced skin turgor i.e. the skin loses its elasticity

Laryngotracheobronchitis complications

Complications in croup are rare. In most series, less than 5% of children who were diagnosed with croup required hospitalization and less than 2% of those who were hospitalized were intubated. Death occurred in approximately 0.5% of intubated patients.

A secondary bacterial infection may result in pneumonia or bacterial tracheitis. Bacterial tracheitis is a life-threatening infection that can arise after the onset of an acute viral respiratory infection 2. In this clinical scenario, the child usually has a mild to moderate illness for 2-7 days, but then develops severe symptoms. These patients typically have a toxic appearance and do not respond well to nebulized racemic epinephrine. Cases of suspected bacterial tracheitis require hospitalization with close observation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and, occasionally, endotracheal intubation. Key bacterial pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus including methicillin-resistant strains (MRSA), group A streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes), Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and anaerobes.

Pulmonary edema, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, lymphadenitis, and otitis media have also been reported in patients diagnosed with croup. Poor ability to maintain adequate oral intake, plus increased insensible fluid losses, can lead to dehydration; as such, patients may require intravenous fluid hydration to stabilize their fluid status.

Laryngotracheobronchitis diagnosis

Children with croup are most often diagnosed based on the parent’s description of the symptoms and a physical exam. Sometimes, a health care provider will listen to a child cough over the phone to identify croup. In a few cases, x-rays or other tests may be needed.

A physical exam may show chest retractions with breathing. When listening to the child’s chest through a stethoscope, the provider may hear:

- Difficulty breathing in and out

- Wheezing

- Decreased breath sounds

An exam of the throat may reveal a red epiglottis. A neck x-ray may reveal a foreign object or narrowing of the trachea.

Laryngotracheobronchitis treatment

The majority of cases of croup can be treated at home. Still croup can be scary, especially if it lands your child in the doctor’s office, emergency room or hospital. Comforting your child and keeping him or her calm are important, because crying and agitation worsen airway obstruction. Hold your child, sing lullabies or read quiet stories. Offer a favorite blanket or toy. Speak in a soothing voice.

If your child’s symptoms persist beyond three to five days or worsen, your child’s doctor may prescribe a type of steroid (glucocorticoid) to reduce inflammation in the airway. Benefits will usually be felt within six hours. Dexamethasone is usually recommended because of its long-lasting effects (up to 72 hours). Adrenaline is useful in children with severe croup and respiratory failure. Adrenaline helps to reduce airway inflammation and improve the child’s symptoms immediately. It’s fast-acting, but its effects wear off quickly.

For severe croup, your child may need to spend time in a hospital. In rare instances, a temporary breathing tube may need to be placed in the child’s windpipe.

Medicines and treatments used at the hospital may include:

- Breathing medicines given with a nebulizer machine

- Steroid medicines given through a vein (IV)

- An oxygen tent placed over a crib

- Fluids given through a vein for dehydration

- Antibiotics given through a vein

Rarely, a breathing tube through the nose or mouth will be needed to help your child breathe.

Figure 2. Croup treatment algorithm

How to treat croup at home

Croup often runs its course within three to five days. In the meantime, keep your child comfortable with a few simple measures:

- Stay calm. It is imperative to ensure that the child is comfortable and as unagitated as possible, this can be done by avoiding stressful procedures and examinations. Comfort or distract your child — cuddle, read a book or play a quiet game. Crying makes breathing more difficult.

- Moisten the air. Although there’s no evidence of benefit from this practice and are not recommended by doctors, many parents believe that humid air helps a child’s breathing. You can use a humidifier or sit with the child in a bathroom filled with steam generated by running hot water from the shower.

- Hold your child in a comfortable upright position. Hold your child on your lap, or place your child in a favorite chair or infant seat. Sitting upright may make breathing easier.

- Offer fluids. For babies, water, breast milk or formula is fine. For older children, soup or frozen fruit pops may be soothing.

- Encourage rest. Sleep can help your child fight the infection.

- Try a fever reducer. If your child has a fever, over-the-counter medicines, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), may help.

- Skip the cold medicines. Over-the-counter cold preparations aren’t recommended for children younger than age 2. Plus nonprescription cough medicines won’t help croup.

Your child’s cough may improve during the day, but don’t be surprised if it returns at night. You may want to sleep near your child or even in the same room so that you can take quick action if your child’s symptoms become severe.

Your child may need to be treated in the emergency room or to stay in the hospital if they:

- Have breathing problems that do not go away or get worse

- Become too tired because of breathing problems

- Have bluish skin color

- Are not drinking enough fluids

Laryngotracheobronchitis prognosis

The prognosis for croup is excellent, and recovery is almost always complete. The majority of patients can be managed successfully as outpatients, without the need for inpatient hospital care. Hospitalization rates vary widely among communities, ranging from 1.5-30% and typically averaging 2-5%. Throughout the 1990s, US hospitalizations averaged approximately 41,000 per year but appear to have subsequently decreased. Fewer than 2% of hospitalized children require intubation. Current use of steroids and nebulized epinephrine for treatment of patients with croup may thwart the need to intubate 3. A 10-year study found a mortality rate of less than 0.5% in intubated patients, although overall exact mortality is not known 4.

Some evidence suggests that hospitalization for croup may be associated with future development of asthma. Children hospitalized for croup have demonstrated higher levels of bronchial hyperresponsiveness and an allergic response to skin testing. Further factors that could contribute to asthma later in life are history of recurrent croup, family history of asthma, and smoking exposure in the home environment.

References- Sobol SE, Zapata S. Epiglottitis and croup. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008 Jun. 41(3):551-66, ix.

- Bernstein T, Brilli R, Jacobs B. Is bacterial tracheitis changing? A 14-month experience in a pediatric intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 1998 Sep. 27(3):458-62.

- Bjornson C, Russell KF, Vandermeer B, et al. Nebulized epinephrine for croup in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Feb 16. CD006619

- Segal AO, Crighton EJ, Moineddin R, Mamdani M, Upshur RE. Croup hospitalizations in Ontario: a 14-year time-series analysis. Pediatrics. 2005 Jul. 116(1):51-5.