Liver cyst

Liver cysts in the adult can be classified as developmental, neoplastic, inflammatory, or miscellaneous lesions 1. Because the clinical implications of and therapeutic strategies for liver cysts vary tremendously according to their causes, the ability to differentiate noninvasively all types of cystic tumors is extremely important. With the rapid advances in imaging techniques over the past 2 decades, including the development of both dynamic spiral computed tomography (CT) and fast magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and the ability to use tailored MR imaging techniques such as MR cholangiopancreatography, most liver cysts can be detected on ultrasound or computerized tomography (CT) scans.

Simple liver cyst or simple hepatic cyst is a common benign abnormal fluid filled sac in the liver and have no malignant potential. Simple liver cysts or hepatic cysts are one of the commonest liver lesions, occurring in ~2-7% of the population 1. There may be a slight female predilection. Simple liver cysts usually cause no signs or symptoms and need no treatment. However, simple liver cysts may become large enough to cause pain or discomfort in the upper right part of the abdomen. Simple liver cyst can be diagnosed on ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

When needed, treatment may include drainage or removal of the cyst.

The cause of simple liver cysts isn’t known, but they may be the result of a malformation present at birth. Rarely, liver cysts may indicate a serious, underlying condition such as:

- Polycystic liver disease, an inherited disorder

- Echinococcus infection (hydatid cyst), a parasitic infection

- Liver cancer

Can liver cysts cause abdominal pain?

Simple liver cysts — fluid-filled cavities in the liver — usually cause no signs or symptoms and requires need no treatment. However, they may become large enough to cause pain or discomfort in the upper right part of the abdomen.

Most liver cysts can be detected on ultrasound or computerized tomography (CT) scans. When needed, treatment may include drainage or removal of the cyst.

The cause of simple liver cysts isn’t known, but they may be the result of a malformation present at birth. Rarely, liver cysts may indicate a serious, underlying condition such as:

- Polycystic liver disease, an inherited disorder

- Echinococcus infection (hydatid cyst), a parasitic infection

- Liver cancer

Liver cyst causes

The cause of most liver cysts is unknown. Liver cysts can be present at birth or can develop at a later time. They usually grow slowly and are not detected until adulthood.

Some liver cysts are caused by a parasite, echinococcus that is found in sheep in different parts of the world.

Simple hepatic cyst

Simple hepatic cysts are benign developmental lesions that do not communicate with the biliary tree 2. The current theory regarding the origin of true hepatic cysts is that they originate from hamartomatous tissue 2. Hepatic cysts are common and are presumed to be present in 2.5% of the population 3. They are more often discovered in women and are almost always asymptomatic 3. Simple hepatic cysts can be solitary or multiple, with the latter being the more typical scenario. At histopathologic analysis, true hepatic cysts contain serous fluid and are lined by a nearly imperceptible wall consisting of cuboidal epithelium, identical to that of bile ducts, and a thin underlying rim of fibrous stroma.

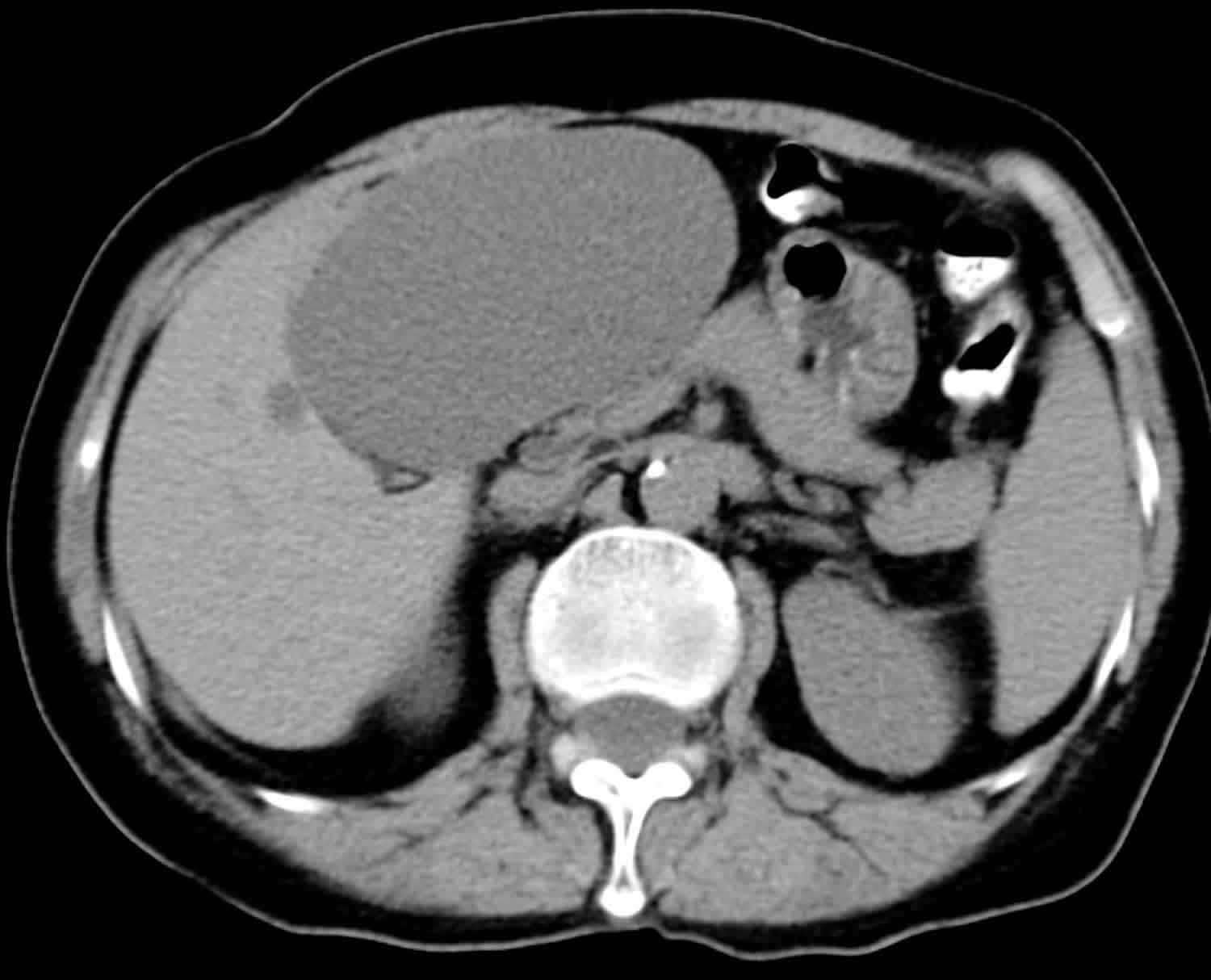

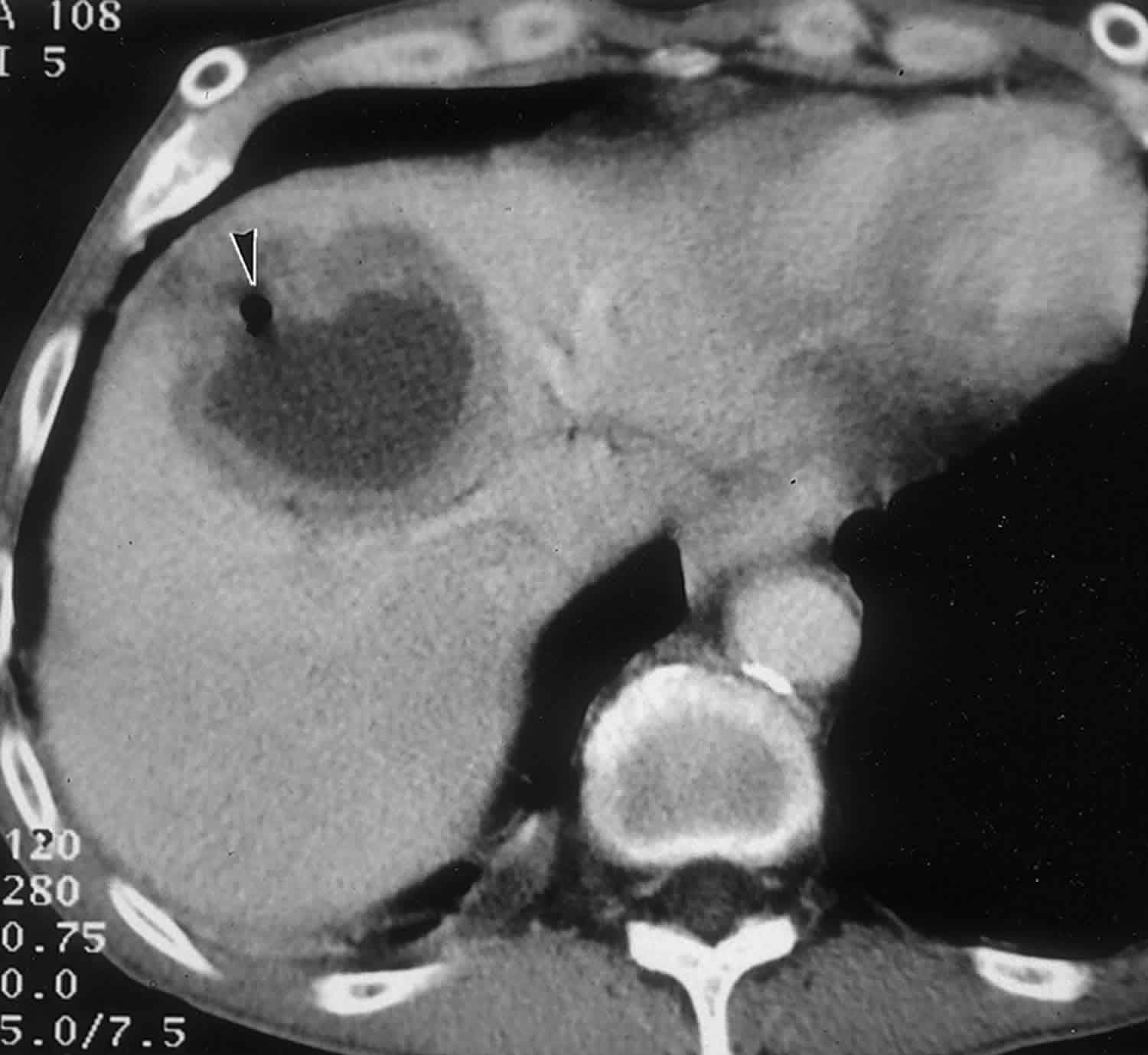

A hepatic cyst appears as a homogeneous and hypoattenuating lesion on nonenhanced CT scans, with no enhancement of its wall or content after intravenous administration of contrast material (Figure 1) 3. It is typically round or ovoid and well-defined 3. At MR imaging, hepatic cysts have homogeneous very low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and homogeneous very high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Owing to their fluid content, an increase in signal intensity is seen on heavily T2-weighted images. This increase allows differentiation of these lesions from metastatic disease. No enhancement is seen after administration of gadolinium chelates.In cases of intracystic hemorrhage, a rare complication in simple hepatic cysts, the signal intensity is high, with a fluid-fluid level, on both T1- and T2-weighted images when mixed blood products are present 3.

On the basis of these features, either CT alone or MR imaging alone is sufficient to establish an accurate diagnosis of a simple hepatic cyst in most cases.

Figure 1. Simple liver cyst

Footnote: Large cystic lesion in the left lobe of the liver. No enhancement. Left lobe liver resection showed two simple cysts, the larger containing necrotic debris. No evidence of neoplasm. No evidence of hydatid cyst.

Polycystic liver disease

Polycystic liver disease is the development of multiple cysts in the liver. Most people with polycystic liver disease also have polycystic kidney disease, which are cysts in the kidneys that can cause high blood pressure and kidney failure. Sometimes a liver transplant and a kidney transplant may be necessary. Polycystic liver disease is an autosomal dominant disorder 2. Although hepatic cysts are found in 40% of cases of autosomal dominant polycystic disease involving the kidneys, they may be seen without identifiable renal involvement at radiography 4. Usually, patients with autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease are asymptomatic and liver dysfunction occurs only sporadically 2. However, advanced disease can result in hepatomegaly, liver failure, or Budd-Chiari syndrome. In these more severe cases, percutaneous interventional alcohol ablation has been useful as an alternative to partial liver resection or even transplantation 2.

Polycystic liver disease cysts may cause pain, but they usually do not affect liver function. If polycystic liver disease starts affecting liver function or becomes too painful, surgery may be needed. However, cysts can reoccur after surgery.

People with polycystic liver disease are born with it, but usually do not have large cysts until they are adults. Polycystic liver disease is genetic. When it is found in one family member, all family members should be tested. Polycystic liver disease may be detected using an ultrasound or CT scan. It is more common in women than men.

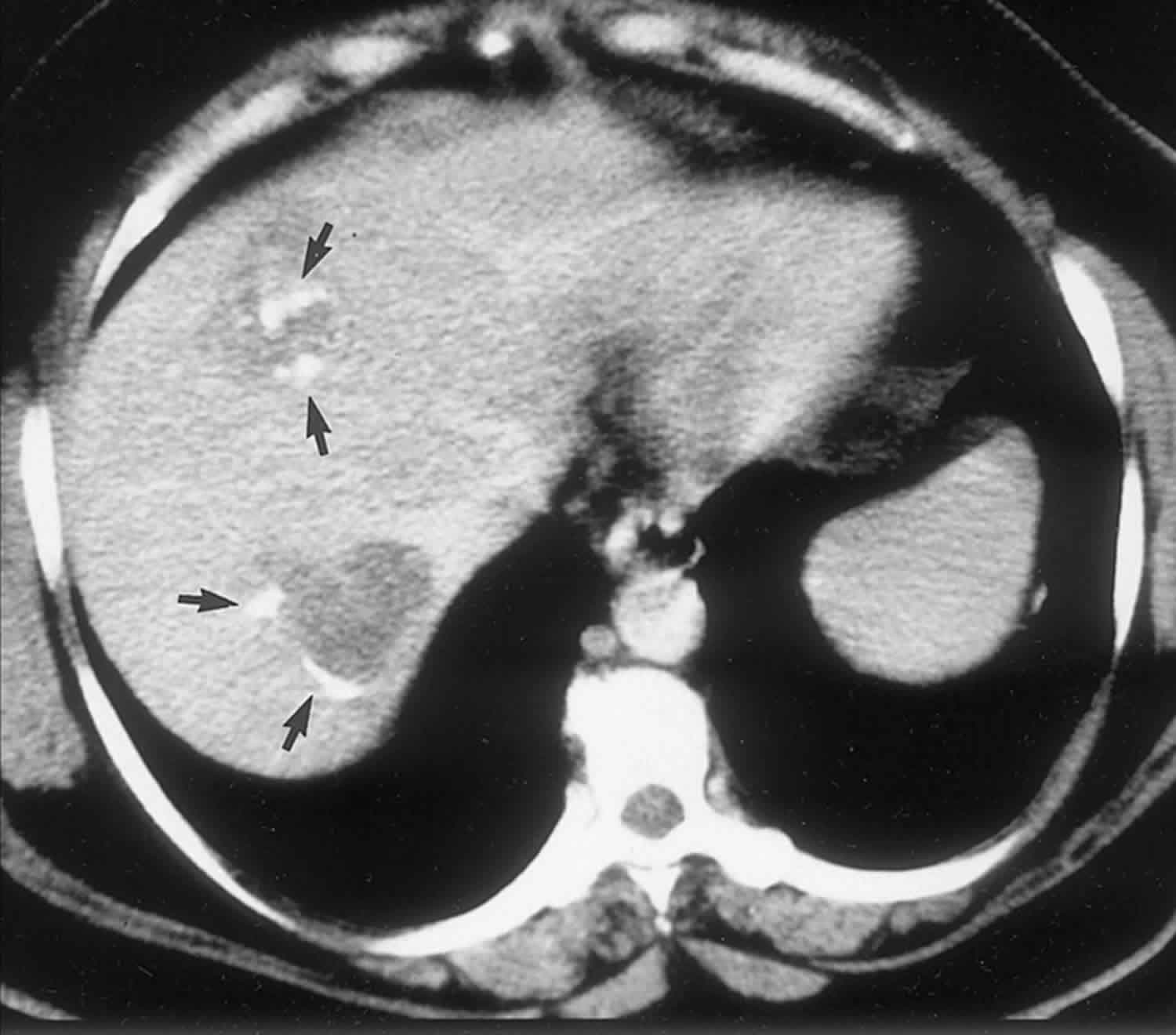

Polycystic liver disease typically appears as multiple homogeneous and hypoattenuating cystic lesions with a regular outline on nonenhanced CT scans, with no wall or content enhancement on contrast-enhanced images (Figure 2). At MR imaging, hepatic cysts in polycystic liver disease have very low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and do not enhance after administration of gadolinium contrast material. Owing to their pure fluid content, homogeneous high signal intensity is demonstrated on T2-weighted and heavily T2-weighted images. In patients with polycystic liver disease, signal intensity abnormalities indicating intracystic hemorrhage are more frequently encountered than in cases of simple hepatic cysts due to the great number of cysts 3. Although the diagnosis of polycystic liver disease is easily made with both CT and MR imaging, MR imaging is more sensitive for the detection of complicated cysts.

Figure 2. Polycystic liver disease cysts

Footnote: Autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease and kidney disease in a 45-year-old patient. Portal-venous-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan shows multiple nonenhancing hepatic and renal cysts (arrowheads).

[Source 1 ]Bile duct hamartoma

Bile duct hamartomas, also called von Meyenburg complexes, originate from embryonic bile ducts that fail to involute 5. They are generally without clinical manifestations and are usually encountered as an incidental finding at imaging, laparotomy, or autopsy 6. At pathologic analysis, they appear as grayish-white nodular lesions 0.1–1.5 cm in diameter that do not communicate with the biliary tree and are scattered throughout the liver parenchyma 6.

In almost all reported cases, nonenhanced CT has shown multiple hypoattenuating, cystlike hepatic nodules occurring throughout both lobes of the liver and typically measuring less than 1.5 cm in diameter 7. The latter feature is the most essential one in the differential diagnosis from multiple simple cysts. Furthermore, simple cysts are typically regularly outlined, whereas bile duct hamartomas have a more irregular outline. Bile duct hamartomas do not exhibit a characteristic pattern of enhancement after intravenous administration of iodinated contrast material. Although homogeneous enhancement of the lesions has been noted in some cases, in most reports no enhancement was seen on contrast-enhanced CT images 8.

The MR imaging appearance of bile duct hamartomas has been reported sporadically 8. All lesions were hypointense relative to liver parenchyma on T1-weighted images and strongly hyperintense on T2-weighted images 5. On heavily T2-weighted images, the signal intensity increases further, almost reaching the signal intensity of fluid 5. At MR cholangiography, bile duct hamartomas appear as multiple tiny cystic lesions that do not communicate with the biliary tree (Figure 3). After intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast material, some authors observed homogeneous enhancement of these lesions (,1,,8), whereas others did not find any enhancement (,9). Recently, thin rim enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced images was reported in four cases (,11) (,,,,Fig 6c). This rim enhancement was considered to correlate with the compressed liver parenchyma that surrounds the lesions at histopathologic analysis (,11).

At both CT and MR imaging, multiple small (<1.5-cm-diameter) cystic lesions in the liver without renal involvement should favor the diagnosis of biliary hamartomas. However, MR imaging is superior to CT in demonstrating the cystic nature of the lesions.

Figure 3. Biliary hamartomas

Footnote: Biliary hamartomas in a 32-year-old woman. Coronal projection MR cholangiogram shows that all of the lesions are smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter and do not communicate with the biliary tree.

[Source 1 ]Caroli disease

Caroli disease also known as congenital communicating cavernous ectasia of the biliary tract, is a rare inherited autosomal recessive involving segmental dilatation of large, intra-hepatic bile ducts and multiple intrahepatic calculi, which appear as cysts on imaging and histopathologic exam 9. The gene involved is the same gene that is responsible for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease; hence, it is commonly seen in conjunction. Two forms of Caroli disease have been described: a less common pure form (type 1) and a more complex form (type 2), which is associated with other ductal plate abnormalities, such as hepatic fibrosis 10. The abnormality may be segmental or diffuse. Caroli disease can frequently lead to congenital hepatic fibrosis, at which point it is called Caroli syndrome, the more common variant 11. Caroli disease is usually diagnosed during adolescence, and patients present with recurrent episodes of cholangitis. Clinical symptoms are usually restricted to recurrent attacks of right upper quadrant pain, fever, and, more rarely, jaundice 4. The prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma is higher in patients with Caroli disease than in the general population 12. Treatment is supportive with antibiotics and if indicated, endoscopic treatment with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for obstruction or impaction.

Figure 4. Caroli disease

Footnote: Caroli disease in a 54-year-old man. Portal-venous-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan shows saccular dilatation of the biliary tree (arrowhead) with enhancement of central portal vein radicals (arrows) (the central dot sign).

[Source 1 ]Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma is a rare malignant hepatic tumor that occurs predominantly in older children and adolescents (mean age, 12 years), although it can occur in young adults as well 13.

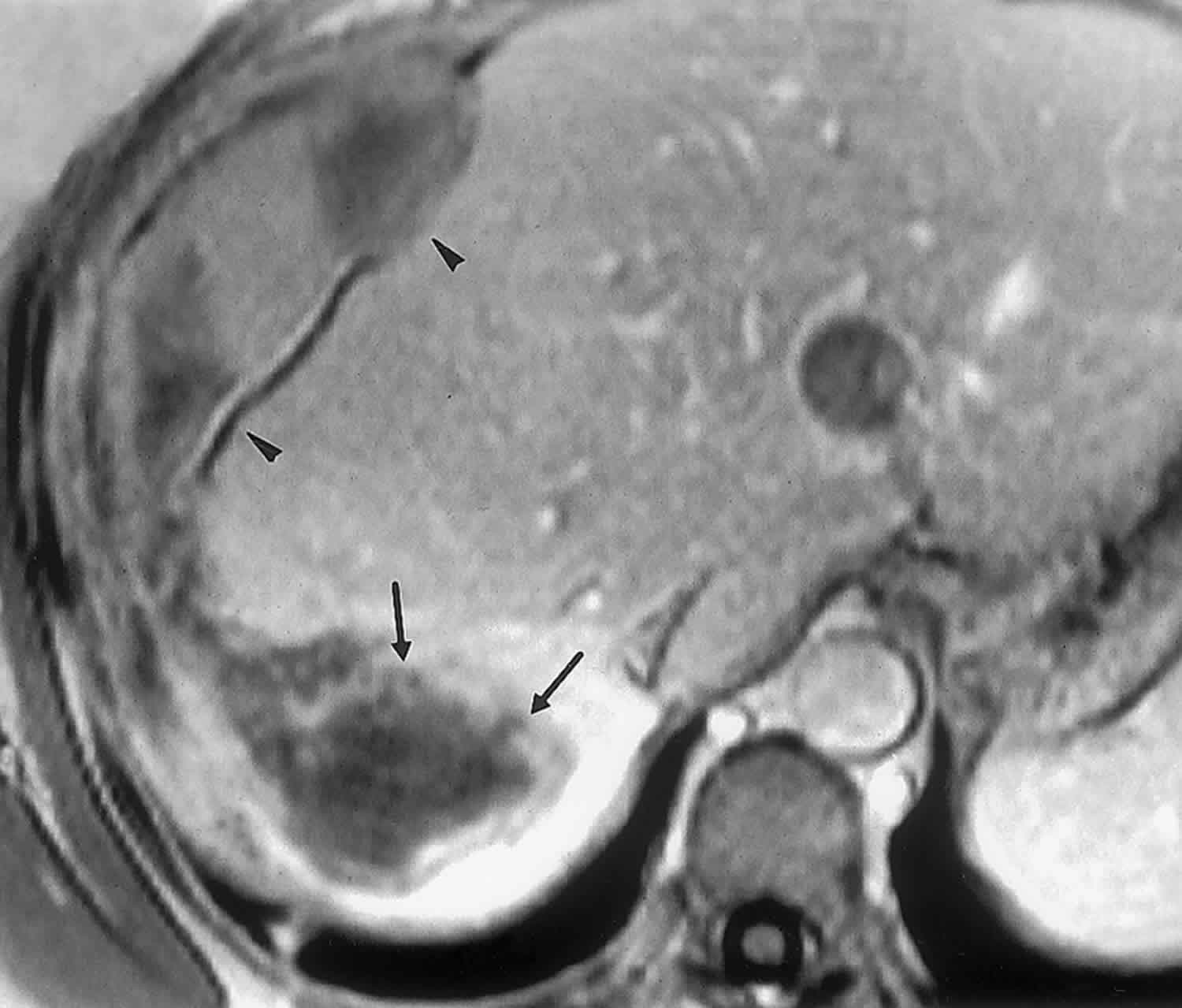

At cross-sectional imaging, the tumor typically appears as a large (10–25-cm-diameter), solitary, predominantly cystic mass with well-defined borders; occasionally, a pseudocapsule separates the mass from normal liver tissue (,15,,16). Internal calcifications have been reported sporadically 13. Although undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma appears predominantly solid at gross examination (83% of cases), CT and MR images usually demonstrate a discordant cystic appearance due to the high water content of the myxoid stroma, which is typical of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma 14. Therefore, at MR imaging, large portions of the mass are hypointense on T1-weighted images and have high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Figure 5) 15. Streaky areas of high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and low signal intensity on T2-weighted images represent intratumoral hemorrhage, a feature better appreciated with MR imaging 15. On contrast-enhanced CT and MR images, heterogeneous enhancement is present in the solid, usually peripheral portions of the mass, especially on delayed images 15.

Figure 5. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma

Footnote: Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma in a 36-year-old woman. T2-weighted MR image shows a mass in the right lobe of the liver. The solid portions of the mass (arrowheads) are hyperintense relative to normal liver tissue, and the cystic portions (arrow) have signal intensity similar to that of water.

[Source 1 ]Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma

Biliary cystadenomas are rare, usually slow growing, multilocular cystic tumors that represent less than 5% of intrahepatic cystic masses of biliary origin 16. Although they are generally intrahepatic (85%), extrahepatic lesions have been reported 16. Among intrahepatic cystadenomas, 55% occur in the right lobe, 29% occur in the left lobe, and 16% occur in both lobes 16. Biliary cystadenomas range in diameter from 1.5 to 35 cm. They occur predominantly in middle-aged women (mean age, 38 years) and are considered premalignant lesions 17. Symptoms are usually related to the mass effect of the lesion and consist of intermittent pain or biliary obstruction 4. At microscopy, a single layer of mucin-secreting cells lines the cyst wall. The fluid within the tumor can be proteinaceous, mucinous, and occasionally gelatinous, purulent, or hemorrhagic due to trauma 17.

At CT, a biliary cystadenoma appears as a solitary cystic mass with a well-defined thick fibrous capsule, mural nodules, internal septa, and rarely capsular calcification (Figure 6) 16. Polypoid, pedunculated excrescences are seen more commonly in biliary cystadenocarcinoma than in cystadenoma, although papillary areas and polypoid projections have been reported in cystadenomas without frank malignancy 18. The MR imaging characteristics of an uncomplicated biliary cystadenoma correlate well with the pathologic features: The appearance of the content is typical for a fluid-containing multilocular mass, with homogeneous low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and homogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images 16. Variable signal intensities on both T1- and T2-weighted images depend on the presence of solid components, hemorrhage, and protein content 16.

Figure 6. Biliary cystadenoma

Footnote: Biliary cystadenoma. Delayed-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained in a 56-year-old woman shows a 12-cm-diameter, multiseptated cystic lesion in the right lobe of the liver. A focal papillary excrescence is noted (arrowhead).

[Source 1 ]Primary liver neoplasms cystic subtypes

Cystic subtypes of primary liver neoplasms are rare and are usually related to internal necrosis following disproportionate growth or systemic and locoregional treatment. Hepatocellular carcinoma and giant cavernous hemangioma are the two most common primary neoplasms of the liver that rarely manifest as an entirely or partially cystic mass.

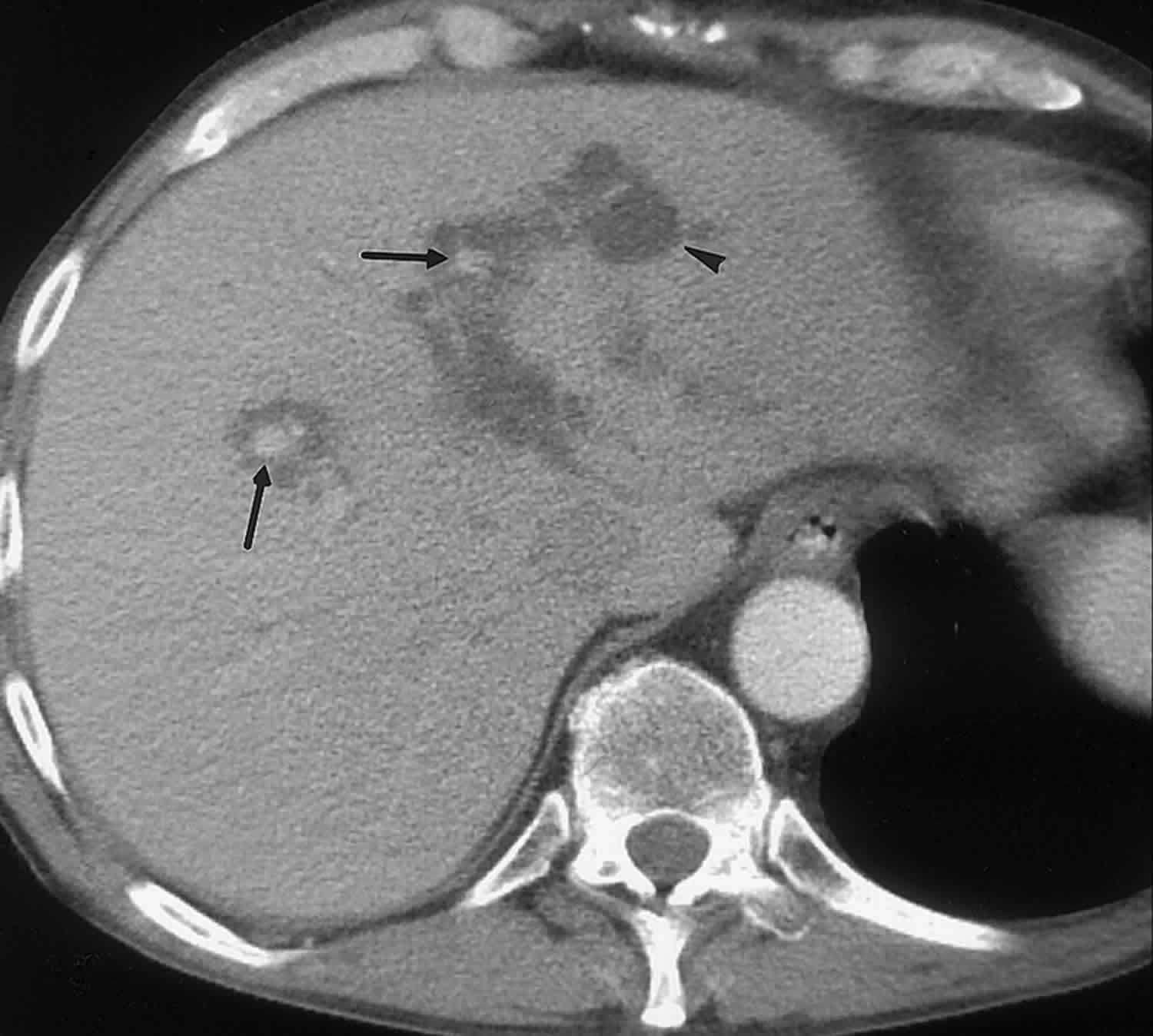

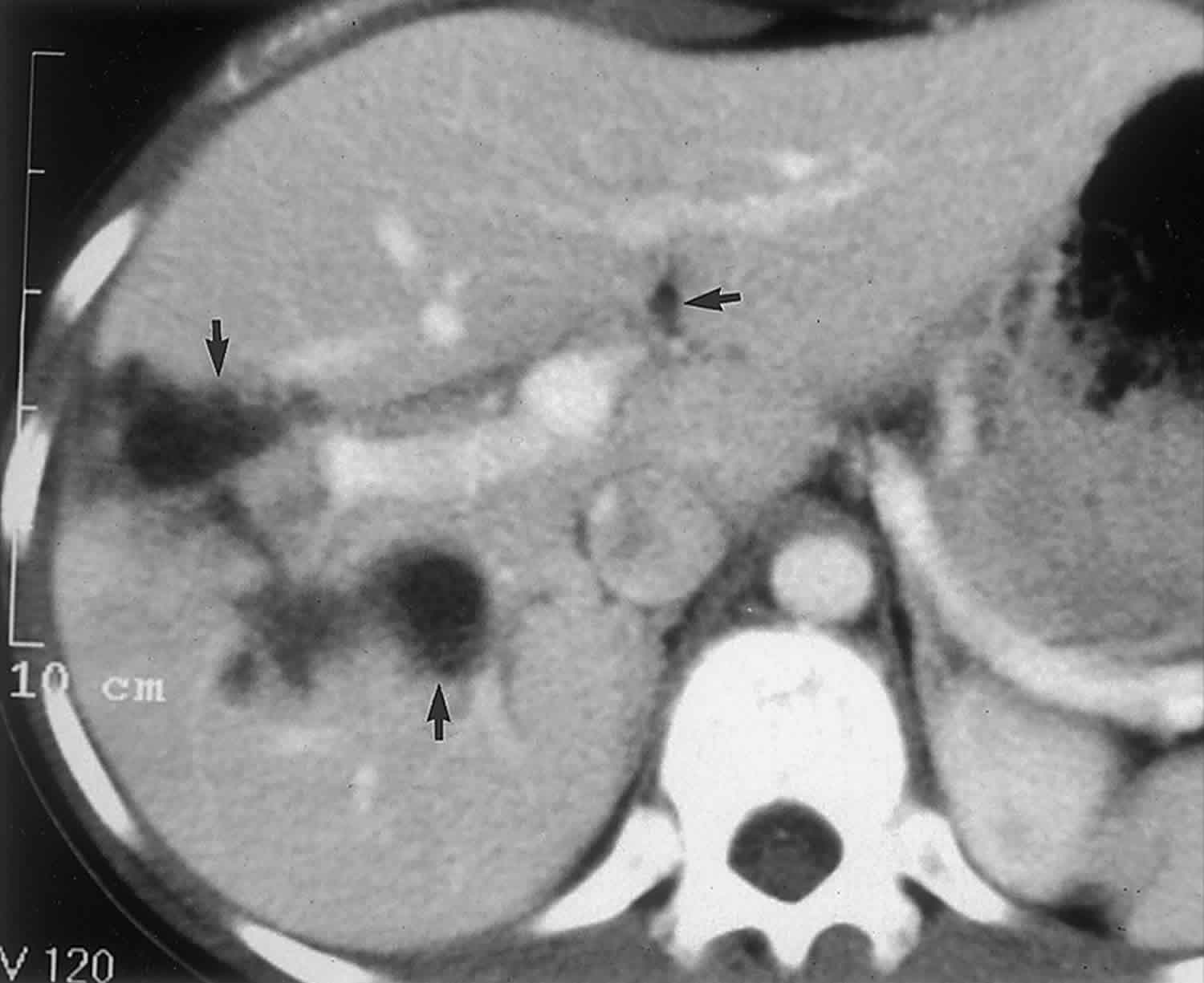

In about 70% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, CT or MR imaging demonstrates signs or complications of underlying liver cirrhosis, such as hypertrophy of the left hepatic lobe and caudate lobe, regeneration nodules, splenomegaly, and recanalization of the umbilical vein 18. In addition, well-defined intrinsic tumor characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma may be present, such as hypervascularity of the solid parts, a capsule, and vascular or biliary invasion. The presence of these indirect signs, even in cases in which the predominant component of the tumor is cystic, should suggest the diagnosis (Figure 7) 4.

Giant cavernous hemangioma can outgrow its blood supply, resulting in central cystic degeneration 19. At CT and MR imaging, a central nonenhancing area is demonstrated within the lesion 19. Since hemangioma has a characteristic peripheral nodular enhancement pattern at both contrast-enhanced CT and contrast-enhanced MR imaging, even lesions with extensive central necrosis are easily diagnosed correctly with both imaging modalities 20.

Figure 7. Cystic hepatocellular carcinoma

Footnote: Cystic hepatocellular carcinoma. Arterial-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained in a 55-year-old man shows indirect signs of liver cirrhosis: atrophy of the right hepatic lobe, hypertrophy of the caudate lobe, contour irregularities, and ascites. In addition, an ill-defined cystic mass is seen in the right hepatic lobe (arrows). A small hypervascular nodule is seen at the periphery of the mass (arrowhead).

[Source 1 ]Cystic metastases

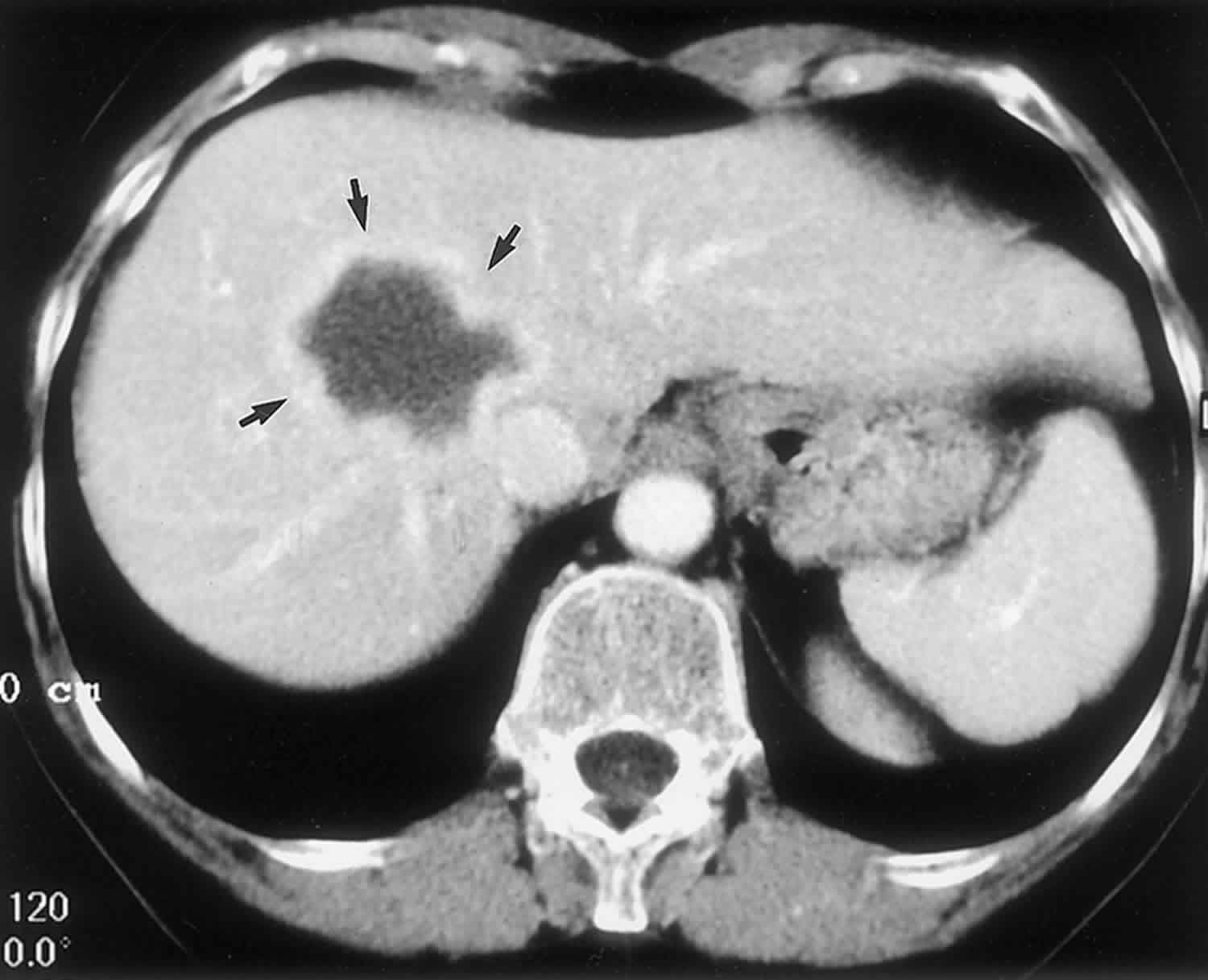

Metastases to the liver are common, and a variety of often nonspecific appearances have been reported 21. Most hepatic metastases are solid, but some have a complete or partially cystic appearance 21. In general, two different pathologic mechanisms can explain the cystlike appearance of hepatic metastases. First, hypervascular metastatic tumors with rapid growth may lead to necrosis and cystic degeneration. This mechanism is frequently demonstrated in metastases from neuroendocrine tumors, sarcoma, melanoma, and certain subtypes of lung and breast carcinoma 21. Contrast-enhanced CT and MR imaging typically demonstrate multiple lesions with strong enhancement of the peripheral viable and irregularly defined tissue (Figure 8) 21. Second, cystic metastases may also be seen with mucinous adenocarcinomas, such as colorectal or ovarian carcinoma 22. Ovarian metastases commonly spread by means of peritoneal seeding rather than hematogenously 23. Therefore, they appear on cross-sectional images as cystic serosal implants on both the visceral peritoneal surface of the liver and the parietal peritoneum of the diaphragm (Figure 8) 23. This appearance is in contradistinction to that of most other cystic hepatic lesions, which are intraparenchymal.

Figure 8. Cystic liver metastasis

Footnote: Cystic metastases. Portal-venous-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained in a 42-year-old woman with metastatic breast carcinoma shows a cystic lesion with peripheral enhancement (arrows).

[Source 1 ]Liver abscess

Liver abscesses can be classified as pyogenic, amebic, or fungal 24. Pyogenic hepatic abscesses are most commonly caused by Clostridium species and gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Bacteroides species, which enter the liver via the portal venous system or biliary tree 24. Ascending cholangitis and portal phlebitis are the most frequent causes of pyogenic hepatic abscesses (,1). An amebic abscess results from infection with the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica and is the most commonly encountered hepatic abscess on a worldwide basis (,26). Fungal abscesses are most often caused by Candida albicans 24. Clinical symptoms of abscesses are related to the coexistence of sepsis and the presence of one or more space-occupying lesions 4.

In general, the presence of air within a lesion, although uncommon, is diagnostic of a gas-forming organism if there is no history of instrumentation or rupture into a hollow viscus (Figure 9). Air is easily recognizable at CT by measuring the Hounsfield units (range, −1,000 to −100 HU). At MR imaging, air appears as a signal void and is therefore more difficult to differentiate from calcifications. However, the shape and location (air-fluid level) should enable correct diagnosis. The overall appearance of a hepatic abscess at cross-sectional imaging varies according to the pathologic stage of the infection 24. Abscesses have a unilocular cystic appearance in subacute stages, in which necrosis and liquefaction predominate 24. In more acute stages, abscesses frequently manifest as a cluster of small low-attenuation or high-signal-intensity lesions, which represent different locations of contamination 4. This coalescent, grouped appearance is especially suggestive of pyogenic infection 4.

Liver abscesses usually appear as thick-walled lesions with homogeneous low attenuation at CT, homogeneous low signal intensity on T1-weighted MR images, and homogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images 24. In addition to the enhancing abscess wall, contrast-enhanced CT and especially contrast-enhanced MR imaging typically show increased peripheral rim enhancement, which is secondary to increased capillary permeability in the surrounding liver parenchyma (the “double target” sign) 25. Perilesion edema is seen on T2-weighted MR images in 50% of abscesses, although it may also be seen in 20%–30% of patients with primary or secondary hepatic malignancies 25. Therefore, the presence of perilesion edema can be used to differentiate a hepatic abscess from a benign cystic hepatic lesion 25.

Figure 9. Liver abscess

Footnote: Liver abscess. Delayed-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained in a 64-year-old man with fever shows a thick-walled cystic lesion with peripheral enhancement. Note the small pocket of air in the nondependent portion of the mass (arrowhead), which is virtually diagnostic of an abscess due to a gas-forming organism.

[Source 1 ]Intrahepatic hydatid cyst

Hepatic echinococcosis is an endemic disease in the Mediterranean basin and other sheep-raising countries 24. Humans become infected by ingestion of eggs of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus, either by eating contaminated food or from contact with dogs 24. The ingested embryos invade the intestinal mucosal wall and proceed to the liver by entering the portal venous system 24. Although the liver filters most of these embryos, those that are not destroyed then become hepatic hydatid cysts 24. At biochemical analysis, there is usually eosinophilia, and a serologic test is positive in 25% of patients 4. At histopathologic analysis, a hydatid cyst is composed of three layers: the outer pericyst, which corresponds to compressed liver tissue; the endocyst, an inner germinal layer; and the ectocyst, a translucent thin interleaved membrane 24.Maturation of a cyst is characterized by the development of daughter cysts in the periphery as a result of endocyst invagination 24. Peripheral calcifications are not uncommon in viable or nonviable cysts 24.

At CT, a hydatid cyst usually appears as a well-defined hypoattenuating lesion with a distinguishable wall 26. Coarse calcifications of the wall are present in 50% of cases (Figure 10), and daughter cysts are identified in approximately 75% of patients 4. MR imaging clearly demonstrates the pericyst, the matrix, and daughter cysts (,29). The pericyst is seen as a hypointense rim on both T1- and T2-weighted images because of its fibrous composition and the presence of calcifications 24. The hydatid matrix (hydatid “sand”) appears hypointense on T1-weighted images and markedly hyperintense on T2-weighted images; when present, daughter cysts are more hypointense than the matrix on T2-weighted images 27.

Figure 10. Hydatid cyst liver

Footnote: Hydatid liver cyst. Portal-venous-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained in a 45-year-old sheep raiser shows two cystic lesions in the liver with subtotally calcified walls (arrows).

[Source 1 ]Hepatic extrapancreatic pseudocyst

Although pancreatic pseudocysts can form anywhere in the abdomen, intrahepatic occurrence is rare 28. They occur predominantly in the left lobe of the liver as a result of extension of fluid from the lesser sac into the leaves of the hepatogastric ligament 28. Clinical symptoms are usually related to the underlying inflammatory pancreatic disease. Elevated serum and urinary amylase levels should arouse suspicion for this condition 28.

Correct diagnosis is not difficult with imaging when other signs of acute pancreatitis are present 28. At CT, a mature intrahepatic pseudocyst appears as a well-defined, subcapsular, homogeneous, hypoattenuating mass surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule (Figure 11) 4. In more acute settings, the attenuation of the fluid within the cyst may be higher due to hemorrhage and necrotic debris, and the lesion may be less distinctly defined 4. At MR imaging, a pancreatic pseudocyst appears as a well-circumscribed subcapsular lesion with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and marked high signal intensity on T2-weighted images 29. In mature cysts, an enhancing capsule is seen following intravenous administration of gadolinium chelates 29. Studies that evaluated the usefulness of MR imaging versus CT in patients with pancreatic fluid collections prior to drainage showed that MR imaging is superior for prediction of drainability 29. T2-weighted MR imaging allows better visualization of fluid and solid components within complex collections and therefore provides essential information about the presence or absence of debris that cannot be removed with standard pseudocyst drainage techniques 29.

Figure 11. Intrahepatic pancreatic pseudocyst

Footnote: Intrahepatic pancreatic pseudocyst. Portal-venous-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan, obtained in a 34-year-old patient after an episode of acute severe pancreatitis 3 weeks earlier, shows multiple intraperitoneal pseudocysts and a 5-cm-diameter cystic lesion in the left lobe of the liver (arrows). The lesion is well-defined due to the presence of a capsule, is homogeneous, and in the clinical context is pathognomonic for an intrahepatic pancreatic pseudocyst.

[Source 1 ]Hepatic hematoma

Surgery and trauma are the two most common causes of hepatic bleeding. Hemorrhage within a solid liver neoplasm, especially a hepatocellular adenoma, is a third well-known mechanism by which intra- or perihepatic hematoma can be induced 30. Symptomatic manifestations depend on the severity of the bleeding, the location, and the time frame during which the hemorrhage occurred.

At CT, the appearance of an intrahepatic hemorrhage depends on the cause of the bleeding and the lag time between the traumatic event and the imaging procedure. In an acute or subacute setting, hemorrhage has a higher attenuation value than pure fluid due to the presence of aggregated fibrin components 31. In chronic cases, a hematoma has attenuation identical to that of pure fluid. Frequently, the cause of the hemorrhage can be detected at CT. In posttraumatic cases, coexistent features such as hepatic lacerations, rib fractures, or perihepatic fluid will be present. In hemorrhage induced by surgery, the location of the hematoma (along the surgical plane) will often be a clue to the diagnosis. The presence of a perihepatic hematoma in combination with a hemorrhagic mass is highly suggestive of hepatocellular adenoma (Figure 12). Because of the paramagnetic effect of methemoglobin, MR imaging is even more suitable than CT for detection and characterization of hemorrhage. A subacute hematoma appears as a heterogeneous mass with pathognomonic high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images 32.

Figure 12. Hepatic hematoma

Footnote: Hepatic hematoma. Portal-venous-phase gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MR image obtained in a 27-year-old woman shows a “cystic” mass (arrows) in the right hepatic lobe with coexistent acute subcapsular hemorrhage (arrowheads). Consequent laparotomy revealed a bleeding hepatocellular adenoma.

[Source 1 ]Hepatic biloma

Hepatic bilomas result from rupture of the biliary system, which can be spontaneous, traumatic, or iatrogenic following surgery or interventional procedures 4. Bilomas can be intrahepatic or perihepatic. Extravasation of bile into the liver parenchyma generates an intense inflammatory reaction, thereby inducing formation of a well-defined pseudocapsule. Clinical manifestations depend on the location and size of the biloma 4.

At both CT and MR imaging, a biloma usually appears as a well-defined or slightly irregular cystic mass without septa or calcifications 4. Also, the pseudocapsule is usually not readily identifiable 4. This imaging appearance, in combination with the clinical history and location, should enable correct diagnosis (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Hepatic biloma

Footnote: Hepatic bilomas in a 21-year-old man with biliary leakage after a severe motor vehicle accident. Follow-up portal-venous-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan shows three intrahepatic collections (arrows) compatible with bilomas. The lesions do not have septa, capsules, or calcifications.

[Source 1 ]Liver cyst symptoms

Most liver cysts do not cause any symptoms. However, if cysts become large, they can cause bloating and pain in the upper right part of your abdomen. Sometimes, liver cysts become large enough that you can feel them through your abdomen.

Liver cyst complications

Liver cysts can have rare complications of liver failure and liver cancer.

Liver cyst diagnosis

Since most liver cysts do not cause any symptoms, they usually are detected only on ultrasounds or computerized tomography (CT) scans. If symptoms do occur, a doctor may perform an abdominal CT scan to look at the liver.

A blood test will rule out a parasite as the cause of the liver cyst.

Liver cyst treatment

Most liver cysts do not need to be treated. However, if cysts get large and painful, they may need to be drained or surgically removed. Cysts also may be surgically removed if they are stopping bile from reaching your intestine.

If a parasite is found, antibiotics are used for treatment.

References- Cystic Focal Liver Lesions in the Adult: Differential CT and MR Imaging Features. Koenraad J. Mortelé and Pablo R. Ros. RadioGraphics 2001 21:4, 895-910 https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.21.4.g01jl16895

- vanSonnenberg E, Wroblicka JT, D’Agostino HB, et al. Symptomatic hepatic cysts: percutaneous drainage and sclerosis. Radiology 1994; 190:387-392.

- Mathieu D, Vilgrain V, Mahfouz A, et al. Benign liver tumors. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 1997; 5:255-288.

- Murphy BJ, Casillas J, Ros PR, et al. The CT appearance of cystic masses of the liver. RadioGraphics 1989; 9:307-322.

- Semelka RC, Hussain SM, Marcos HB, Woosley JT. Biliary hamartomas: solitary and multiple lesions shown on current MR techniques including gadolinium enhancement. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 10:196-201.

- Wei SC, Huang GT, Chen CH, et al. Bile duct hamartomas: a report of two cases. J Clin Gastroenterol 1997; 25:608-611.

- Wohlgemuth WA, Böttger J, Bohndorf K. MRI, CT, US and ERCP in the evaluation of bile duct hamartomas (von Meyenburg complex): a case report. Eur Radiol 1998; 8:1623-1626.

- Maher MM, Dervan P, Keogh B, Murray JG. Bile duct hamartomas (von Meyenburg complexes): value of MR imaging in diagnosis. Abdom Imaging 1999; 24:171-173.

- Umar J, John S. Caroli Disease. [Updated 2019 Apr 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513307

- Zangger P, Grossholz M, Mentha G, Lemoine R, Graf JD, Terrier F. MRI findings in Caroli’s disease and intrahepatic pigmented calculi. Abdom Imaging 1995; 20:361-364.

- Romine MM, White J. Role of Transplant in Biliary Disease. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2019 Apr;99(2):387-401.

- Pavone P, Laghi A, Catalano C, Materia A, Basso N, Passariello R. Caroli’s disease: evaluation with MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

- Buetow PC, Rao P, Marshall WH. Imaging of pediatric liver tumors. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 1997; 5:397-413.

- Buetow PC, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, et al. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver: pathologic basis of imaging findings in 28 cases. Radiology 1997; 203:779-783.

- Yoon W, Kim JK, Kang HK. Hepatic undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma: MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1997; 21:100-102.

- Palacios E, Shannon M, Solomon C, et al. Biliary cystadenoma: ultrasound, CT, and MRI. Gastrointest Radiol 1990; 15:313-316.

- Buetow PC, Midkiff RB. Primary malignant neoplasms in the adult. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 1997; 5:289-318.

- Powers C, Ros PR, Stoupis C, et al. Primary liver neoplasms: MR imaging with pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics 1994; 14:459-482.

- Vilgrain V, Boulos L, Vullierme MP, Denys A, Terris B, Menu Y. Imaging of atypical hemangiomas of the liver with pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics 2000; 20:379-397.

- Semelka RC, Sofka CM. Hepatic hemangiomas. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 1997; 5:241-253.

- Lewis KH, Chezmar JL. Hepatic metastases. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 1997; 5:319-330.

- Sugawara Y, Yamamoto J, Yamasaki S, Shimada K, Kosuge T, Sakamoto M. Cystic liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2000; 74:148-152.

- Lundstedt C, Holmin T, Thorvinger B. Peritoneal ovarian metastases simulating liver parenchymal masses. Gastrointest Radiol 1992; 17:250-252.

- Mergo PJ, Ros PR. MR imaging of inflammatory disease of the liver. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 1997; 5:367-376.

- Mendez RJ, Schiebler ML, Outwater EK, et al. Hepatic abscesses: MR imaging findings. Radiology 1994; 190:431-436.

- De Liego J, Lecumberri FJ, Francquet T, et al. Computed tomography in hepatic echinococcosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982; 13:699-702.

- Marani SA, Canossi GC, Nicoli FA, et al. Hydatid disease: MR imaging study. Radiology 1990; 175:701-706.

- Okunda K, Sugita S, Tsukada E, et al. Pancreatic pseudocyst in the left hepatic lobe: a report of two cases. Hepatology 1991; 13:359-363.

- Morgan DE, Baron TH, Smith JK, Robbin ML, Kenney PJ. Pancreatic fluid collections prior to intervention: evaluation with MR imaging compared with CT and US. Radiology 1997; 203:773-778.

- Casillas VJ, Amendola MA, Gascue A, Pinnar N, Levi JU, Perez JM. Imaging of nontraumatic hemorrhagic hepatic lesions. RadioGraphics 2000; 20:367-378.

- Merrine D, Fishman EK, Zerhouni EA. Spontaneous hepatic hemorrhage: clinical and CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1988; 12:397-400.

- Balci NC, Semelka RC, Noone TC, Ascher SM. Acute and subacute liver-related hemorrhage: MRI findings. Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 17:207-211.