Short bowel syndrome

Short bowel syndrome also known as short gut syndrome, is a kind of malabsorption disorder in which your body is unable to absorb enough nutrients from the foods you eat because you don’t have enough small intestine either due to functional loss or loss of a portion of the small or large intestine during congenital deficiency (necrotizing enterocolitis) or acquired conditions. Most commonly this occurs after bowel resection in the newborn period (i.e., secondary to necrotizing enterocolitis). Short bowel syndrome is a rare condition. Each year, short bowel syndrome affects about three out of every million people 1.

The small intestine is where the majority of the nutrients you eat are absorbed into your body during digestion. The amount of bowel that must be lost to produce malabsorption is variable and depends on which section(s) is/are lost, and whether the ileocecal valve is preserved. The normal length of small intestine is approximately 300 to 850 cm for an adult, 200 to 250 cm for an infant over 35 weeks gestation, and approximately 100 to 120 cm for a premature infant, less than 30 weeks gestation. Loss of greater than 80% of the small bowel is associated with increased requirement for parenteral nutrition support, and decreased overall survival 2. The ileocecal valve is the main barrier between the small and large intestine. It helps regulate the exit of fluid and malabsorbed nutrients from the small bowel. It also helps keep bacteria from the large bowel from refluxing into the small bowel. Resection of the ileocecal valve results in decreased fluid and nutrient absorption, and increased bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel 3. When the ileocecal valve is lost, the resulting bacterial contamination of the small intestine mandates more small intestine for tolerance of oral/enteral feeding 2.

The small intestine consists of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. The majority of carbohydrate and protein absorption takes place in the duodenum and jejunum. Fats and fat soluble vitamins, however are absorbed in the ileum. Bile salts are excreted from the liver into the duodenum; these are required for the absorption of long chain fatty acids and fat soluble vitamins in the ileum. Vitamin B12 binds to intrinsic factor (produced in the stomach) and is also absorbed in the terminal ileum. Fluids and electrolytes are predominantly absorbed in the ileum and in the colon. When the duodenum and/or jejunum are resected, the ileum can largely adapt to perform their absorptive functions. However, the duodenum and jejunum cannot adapt to perform the functions of the ileum. Thus, resection of the duodenum or jejunum is generally much better tolerated than resection of the ileum.

Short bowel syndrome typically occurs in people who have:

- Had at least half of their small intestine removed and sometimes all or part of their large intestine removed. Conditions that may require surgical removal of large portions of the small intestine include Crohn’s disease, cancer, traumatic injuries and blood clots in the arteries that provide blood to the intestines.

- Significant damage of the small intestine.

- Portions of the small intestine are missing or damaged at birth. Babies may be born with a short small intestine or with a damaged small intestine that must be surgically removed.

- Poor motility, or movement, inside the intestines.

Short bowel syndrome may be mild, moderate, or severe, depending on how well the small intestine is working.

People with short bowel syndrome cannot absorb enough water, vitamins, minerals, protein, fat, calories, and other nutrients from food. What nutrients the small intestine has trouble absorbing depends on which section of the small intestine has been damaged or removed.

Short bowel syndrome treatment typically involves special diets and nutritional supplements and may require nutrition through a vein (parenteral nutrition) to prevent malnutrition.

Intestinal adaptation

Intestinal adaptation is a process that usually occurs in children after removal of a large portion of their small intestine. The remaining small intestine goes through a period of adaptation and grows to increase its ability to absorb nutrients. Intestinal adaptation can take up to 2 years to occur, and during this time a person may be heavily dependent on parenteral or enteral nutrition 4.

Short bowel syndrome causes

Causes of short bowel syndrome include having parts of your small intestine removed during surgery, or being born with some of the small intestine missing or with part of their bowel missing or damaged. Conditions that may require surgical removal of portions of the small intestine include Crohn’s disease, cancer, injuries, and blood clots. The main cause of short bowel syndrome is surgery to remove a portion of the small intestine. This surgery can treat intestinal diseases, injuries, or birth defects. In infants, short bowel syndrome most commonly occurs following surgery to treat necrotizing enterocolitis, a condition in which part of the tissue in the intestines is destroyed.

In children the main causes include necrotizing enterocolitis, intestinal atresias, and intestinal volvulus 5.

The causes of short bowel syndrome in adults include Crohn disease, mesenteric ischemia, radiation enteritis, or surgical removal of half or more of the small intestine to treat intestinal diseases or injuries.

Short bowel syndrome may also occur following surgery to treat conditions such as:

- Cancer and damage to the intestines caused by cancer treatment

- Crohn’s disease, a disorder that causes inflammation, or swelling, and irritation of any part of the digestive tract

- Gastroschisis, which occurs when the intestines stick out of the body through one side of the umbilical cord

- Internal hernia, which occurs when the small intestine is displaced into pockets in the abdominal lining

- Intestinal atresia, which occurs when a part of the intestines doesn’t form completely

- Intestinal injury from loss of blood flow due to a blocked blood vessel

- Intestinal injury from trauma

- Intussusception, in which one section of either the large or small intestine folds into itself, much like a collapsible telescope

- Meconium ileus, which occurs when the meconium, a newborn’s first stool, is thicker and stickier than normal and blocks the ileum

- Midgut volvulus, which occurs when blood supply to the middle of the small intestine is completely cut off

- Omphalocele, which occurs when the intestines, liver, or other organs stick out through the navel, or belly button

Even if a person does not have surgery, disease or injury can damage the small intestine.

Short bowel syndrome symptoms

The main symptom of short bowel syndrome is diarrhea, loose, watery stools. Diarrhea can lead to dehydration, malnutrition, and weight loss. Dehydration means the body lacks enough fluid and electrolytes—chemicals in salts, including sodium, potassium, and chloride—to work properly. Malnutrition is a condition that develops when the body does not get the right amount of vitamins, minerals, and nutrients it needs to maintain healthy tissues and organ function. Loose stools contain more fluid and electrolytes than solid stools. These problems can be severe and can be life threatening without proper treatment.

People with short bowel syndrome are also more likely to develop food allergies and sensitivities, such as lactose intolerance. Lactose intolerance is a condition in which people have digestive symptoms—such as bloating, diarrhea, and gas—after eating or drinking milk or milk products.

Short bowel syndrome other signs and symptoms may include:

- cramping,

- bloating,

- heartburn,

- food sensitivities,

- weakness,

- fatigue or feeling tired

- foul-smelling stool

- too much gas

- vomiting.

People who have any signs or symptoms of severe dehydration should call or see a health care provider right away:

- excessive thirst

- dark-colored urine

- infrequent urination

- lethargy, dizziness, or faintness

- dry skin

Infants and children are most likely to become dehydrated. Parents or caretakers should watch for the following signs and symptoms of dehydration:

- dry mouth and tongue

- lack of tears when crying

- infants with no wet diapers for 3 hours or more

- infants with a sunken soft spot

- unusually cranky or drowsy behavior

- sunken eyes or cheeks

- fever

If left untreated, severe dehydration can cause serious health problems:

- organ damage

- shock—when low blood pressure prevents blood and oxygen from getting to organs

- coma—a sleeplike state in which a person is not conscious

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies can lead to some specific symptoms, as follows:

- Patients with vitamin A deficiencies may report night blindness and xerophthalmia

- Vitamin D depletion can be associated with paresthesias and tetany

- Loss of vitamin E can cause paresthesias, ataxic gait, and visual disturbances because of retinopathy

- A history of easy bruisability or prolonged bleeding might suggest vitamin K depletion

- Patients reporting dyspnea on exertion or lethargy may be anemic from vitamin B12, folic acid, or iron deficiency

- Calcium and magnesium losses can cause paresthesias and tetany

- Patients with critically low zinc levels may describe anorexia and diarrhea

Short bowel syndrome complications

Short bowel syndrome complications may include:

- malnutrition

- peptic ulcers—sores on the lining of the stomach or duodenum caused by too much gastric acid

- kidney stones—solid pieces of material that form in the kidneys

- small intestinal bacterial overgrowth—a condition in which abnormally large numbers of bacteria grow in the small intestine

Both non-transplant and transplant patients can experience the typical postoperative complications of surgical patients in general. These include hemorrhage, wound complications, postoperative pulmonary dysfunction, renal failure, and pulmonary embolism, to name a few.

In non-transplant patients, the following postoperative complications may occur:

- Bowel obstruction

- Bowel necrosis

- Bowel dysmotility and dysfunction

- Anastomotic disruption

- Stasis of intestinal contents with or without bacterial overgrowth

Transplant recipients are subject to all the complications mentioned above. In addition, they may develop serious and sometimes lethal complications specifically related to transplantation and immunosuppression, such as the following:

- Acute rejection

- Chronic rejection

- Hepatic, portal, or mesenteric vein thrombosis

- Systemic sepsis with ordinary pathogens or opportunistic organisms (eg, cytomegalovirus)

- Lymphoproliferative disorders or malignancies.

Short bowel syndrome diagnosis

A health care provider diagnoses short bowel syndrome based on

- a medical and family history

- a physical exam

- blood tests

- fecal fat tests

- an x-ray of the small and large intestines

- upper gastrointestinal (GI) series

- computerized tomography (CT) scan

Medical and Family History

Taking a medical and family history may help a health care provider diagnose short bowel syndrome. He or she will ask the patient about symptoms and may request a history of past operations.

Physical Exam

A physical exam may help diagnose short bowel syndrome. During a physical exam, a health care provider usually

- examines a patient’s body, looking for muscle wasting or weight loss and signs of vitamin and mineral deficiencies

- uses a stethoscope to listen to sounds in the abdomen

- taps on specific areas of the patient’s body

Laboratory studies

The complete blood count (CBC) is an important laboratory test in the workup of the patient with short-bowel syndrome. The primary reason to order this test is to determine if the patient is anemic. The type of anemia can correlate with specific nutritional deficiencies. These include the hypochromic microcytic anemia typical of depleted iron stores and the megaloblastic anemia associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

The plasma albumin level is an important indicator of overall nutritional status. This protein has a half-life of approximately 21 days. Evidence is accumulating that severely depressed albumin levels, especially below 2.5 g/dL, are associated with increased rates of major morbidity and mortality in surgical patients. In addition, albumin is a good indicator of hepatic protein synthesis. Note that during periods of stress or infection, the liver produces acute-phase reactants (eg, C-reactive protein [CRP]) in preference to albumin.

In contrast to the above, an abnormally elevated albumin level may be observed rarely and is consistent with dehydration.

Prealbumin is a good indicator of acute nutritional status. Its half-life is approximately 3-5 days. Many nutrition support practitioners use this protein to monitor the efficacy of nutrition support regimens in their patients. Because of the relatively short half-life, it is not a good nutritional screening tool; albumin is better for this purpose. Prealbumin levels can also be skewed by hydration status and renal function.

Hepatocellular enzymes (eg, aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT]) are important to monitor, especially in patients receiving long-term parenteral nutritional support. Many patients on long-term parenteral nutritional support have transient elevations of these enzymes that subsequently normalize, especially as they begin or increase oral food intake.

Concern should be raised when patients have persistent elevation of the enzymes, especially when they continue to increase. This is the group of patients that may progress to true histologic hepatocellular damage, cirrhosis, and liver failure.

Serum bilirubin is a good indicator of liver function, but its sensitivity for early liver damage probably is less than that of the hepatocellular enzymes.

In patients with liver dysfunction that is suggested by biochemical or radiologic modalities, procurement of a tissue specimen may be advisable. Liver biopsies can be performed percutaneously under the guidance of ultrasonography or CT.

Measure standard serum chemistries, including sodium, potassium, chloride, and carbon dioxide–combining power, frequently in patients on long-term parenteral nutrition. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is commonly associated with disturbances in these values, and simple adjustments in the concentration of these are usually sufficient to correct the problem.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) determinations are important because they provide an indication of renal reserve or function. More important, in this patient group, rising BUN levels may indicate that the patient is being overfed with protein. Alternately, if BUN levels are disproportionately elevated in relation to creatinine (>20:1), the patient may be dehydrated.

Serum creatinine is a good indicator of renal function. Rising creatinine should raise concern about deteriorating renal function and may necessitate changes in the nutrition support regimen.

The divalent cations calcium and magnesium and the anion phosphorus are important in several cellular processes. Calcium and magnesium facilitate functioning of many enzyme systems, regulate membrane stabilization and excitation, and serve important functions in cardiac conduction and elsewhere. Phosphorus (as phosphates) and proteins are the major intracellular anions. Phosphorus is also involved in the generation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the major energy substrate of aerobic cells. Suspect loss of these ions in patients with severe diarrhea, especially steatorrhea.

Calculation of nitrogen balance allows the clinician to investigate whether adequate amounts of protein are being supplied to a particular patient. To perform this test, a 24-hour urine collection is obtained, and the amount of urinary urea nitrogen is measured. The amount of protein (Pr) the patient is being fed is a known variable (g Pr). These values are applied to the following equation:

- Nitrogen balance = g of protein the patient is being fed/6.25 – (urinary urea nitrogen + 4 g)

For every 6 g of protein, 1 g of nitrogen is present. The figure 4 g is for fecal losses. The fecal protein loss can be much higher in patients with short-bowel syndrome, malabsorption, and diarrhea.

Attaining positive nitrogen balance is important. It is associated with proper immune function, good wound healing, replenishment of lean body mass in previously catabolic patients, and growth in children.

Vitamin levels can be measured in serum. This is achieved best when a specific abnormality that can be attributed to a vitamin deficiency is suspected on clinical grounds. Treat vitamin deficiency by supplementation of that vitamin.

Serum levels of zinc, chromium, selenium, and other important minerals and trace elements can also be measured. Most of these elements serve as cofactors in various metalloenzyme systems. Their depletion leads to degradation in enzyme function and, sometimes, serious clinical sequelae, some of which have been described. Treat a deficiency in one of these elements by replenishment, especially if a related clinical disorder (eg, glucose intolerance and chromium deficiency) is present.

Treat a deficiency in one of these elements by replenishment, especially if a related clinical disorder (eg, glucose intolerance and chromium deficiency) is present.

Fecal fat tests

A fecal fat test measures the body’s ability to break down and absorb fat. For this test, a patient provides a stool sample at a health care provider’s office. The patient may also use a take-home test kit. The patient collects stool in plastic wrap that he or she lays over the toilet seat and places a sample into a container. A patient can also use a special tissue provided by the health care provider’s office to collect the sample and place the tissue into the container. For children wearing diapers, the parent or caretaker can line the diaper with plastic to collect the stool. The health care provider will send the sample to a lab for analysis. A fecal fat test can show how well the small intestine is working.

X-ray

An x-ray is a picture created by using radiation and recorded on film or on a computer. The amount of radiation used is small. An x-ray technician performs the x-ray at a hospital or an outpatient center, and a radiologist—a doctor who specializes in medical imaging—interprets the images. An x-ray of the small intestine can show that the last segment of the large intestine is narrower than normal. Blocked stool causes the part of the intestine just before this narrow segment to stretch and bulge.

Upper gastrointestinal series

Upper GI series, also called a barium swallow, uses x rays and fluoroscopy to help diagnose problems of the upper GI tract. Fluoroscopy is a form of x ray that makes it possible to see the internal organs and their motion on a video monitor. An x-ray technician performs this test at a hospital or an outpatient center, and a radiologist interprets the images.

During the procedure, the patient will stand or sit in front of an x-ray machine and drink barium, a chalky liquid. Barium coats the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine so the radiologist and a health care provider can see the shape of these organs more clearly on x-rays.

A patient may experience bloating and nausea for a short time after the test. For several days afterward, barium liquid in the GI tract causes white or light-colored stools. A health care provider will give the patient specific instructions about eating and drinking after the test. Upper GI series can show narrowing and widening of the small and large intestines.

Computerized tomography scan

Computerized tomography scans use a combination of x-rays and computer technology to create images. For a CT scan, a health care provider may give the patient a solution to drink and an injection of a special dye, called a contrast medium. CT scans require the patient to lie on a table that slides into a tunnel-shaped device that takes x-rays.

An x-ray technician performs the procedure in an outpatient center or a hospital, and a radiologist interprets the images. The patient does not need anesthesia. CT scans can show bowel obstruction and changes in the intestines.

Other tests

Many patients with short-bowel syndrome develop biliary sludge or gallstones. Symptoms consistent with biliary colic or cholelithiasis can be investigated with abdominal ultrasonography. This study provides important information, such as indicating the presence or absence of stones, gall bladder wall thickness, and common bile duct diameter. Choledocholithiasis and fatty change of the liver may be demonstrated as well.

Patients with short-bowel syndrome, especially those on prolonged courses of total parenteral nutrition (TPN), can develop metabolic bone disease. The major mechanism is calcium and vitamin D malabsorption. Bone can become decalcified (less dense) and more prone to fracture. In this situation it is useful to obtain an estimate of bone density.

Bone density is estimated by dual radiographic absorptiometry. Bone mineral density is measured in terms of g/cm². The patient’s bone density is measured and compared to reference values. A determination is made as to whether or not the patient is osteopenic. Patients deemed osteopenic could be treated with estrogen; calcitonin; bisphosphonates; or supplementation of calcium, vitamin D, and magnesium. Patients may be advised to increase their activity level as well.

Short bowel syndrome treatment

Short bowel syndrome treatment usually involves following a special diet and taking nutritional supplements. Some people may need to get nutrition through a vein to prevent malnutrition. In some cases, intestinal surgeries and intestinal transplantation are needed.

Most survivors of massive bowel resections who develop short-bowel syndrome are initially fed by means of total parenteral nutrition (total parenteral nutrition (TPN)). In these patients, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) prevents the development of malnutrition and has been shown to benefit patient outcomes. total parenteral nutrition (TPN) may be administered concurrently with enteral nutrition early in the clinical course of short-bowel syndrome because the ultimate goal in many of these patients is to enhance intestinal adaptation and render patients free of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) as described by Wilmore et al in animal models 6.

In many patients, intestinal adaptation, alone or in combination with modified and supplemented diets (eg, growth hormone, glutamine, high carbohydrate, low fat) as described by Byrne et al, eventually allows liberation from total parenteral nutrition (TPN) 7.

Unfortunately, some patients are extremely difficult or impossible to wean from parenteral nutrition. Common characteristics of these patients include very short remaining small-bowel segments (< 60 cm), loss of the colon, loss of the ileocecal valve, or small-bowel strictures with stasis and bacterial overgrowth.

total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is not a panacea. Access sites become infected or the cannulated vein thromboses, necessitating replacement. Eventually, the patient may run out of usable veins for access to deliver total parenteral nutrition (TPN). In addition to these mechanical and infectious complications, many serious metabolic complications are associated with long-term use of total parenteral nutrition (TPN). The most clinically important of these are hepatic and biliary derangements. In fact, according to Vanderhoof, advanced liver disease currently is the most common cause of death of patients with short-bowel syndrome 8.

Early in the course of therapy with total parenteral nutrition (TPN), nonspecific elevations in hepatic transaminases can be found. Frequently, these biochemical abnormalities are self-limited and require no specific alteration or curtailment of therapy.

The most frequent manifestation of hepatobiliary disease in patients with short-bowel syndrome who are on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is cholestasis 9. Biliary sludge or gallstones are found in approximately 50% of patients receiving total parenteral nutrition (TPN) with no oral intake for 3 months.

Progressive hepatic parenchymal damage is the most feared hepatobiliary complication of prolonged total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Fatty liver is often observed in adults. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis has features of fatty change but is associated with inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrosis. Progressive cholestasis and liver injury can lead to outright portal fibrosis or cirrhosis, portending progression to liver failure and a poor outcome. Patients with persistent liver function abnormalities should be identified before progression to cirrhosis to assess candidacy for intestinal transplantation.

Moreno et al 10 reported complication rates and survival data for their cohort of 74 patients maintained on long-term home parenteral nutrition for short-bowel syndrome. There were 94 significant complications in the group, most of them infectious. At the end of the year, 74.3% of the patients remained on total parenteral nutrition (TPN). The most common cause for termination of support in the other 23.6% was death (52.9%). Others either were switched to enteral nutritional support (11.8%) or could be liberated from specialized nutritional support to return to an oral diet (23.5%).

No firm absolute contraindications to surgery exist in patients with short-bowel syndrome. The only exception to this might be the creation of a small intestinal valve, designed to increase transit time, in a patient who already has stasis or bacterial overgrowth.

Patients who are severely malnourished with very low albumin or prealbumin levels and those with systemic sepsis or with severe coagulopathy because of advanced liver disease should have these conditions corrected before undergoing surgery.

The decision to operate on a patient with short-bowel syndrome requires great judgment. Surgery is undertaken in these patients usually only after all other therapeutic options, such as parenteral and enteral nutrition or pharmacologic bowel compensation, have been exhausted. Others may require operation because of the complications of prolonged parenteral nutrition or stasis of enteric contents and bacterial overgrowth.

Nutritional Support

The main treatment for short bowel syndrome is nutritional support, which may include the following:

- Oral rehydration. Adults should drink water, sports drinks, sodas without caffeine, and salty broths. Children should drink oral rehydration solutions—special drinks that contain salts and minerals to prevent dehydration—such as Pedialyte, Naturalyte, Infalyte, and CeraLyte, which are sold in most grocery stores and drugstores.

- Parenteral nutrition. This treatment delivers fluids, electrolytes, and liquid vitamins and minerals into the bloodstream through an intravenous (IV) tube—a tube placed into a vein. Health care providers give parenteral nutrition to people who cannot or should not get their nutrition or enough fluids through eating.

- Enteral nutrition. This treatment delivers liquid food to the stomach or small intestine through a feeding tube—a small, soft, plastic tube placed through the nose or mouth into the stomach. Gallstones—small, pebblelike substances that develop in the gallbladder—are a complication of enteral nutrition.

- Vitamin and mineral supplements. A person may need to take vitamin and mineral supplements during or after parenteral or enteral nutrition.

- Special diet. A health care provider can recommend a specific diet plan for the patient that may include:

- small, frequent feedings

- avoiding foods that can cause diarrhea, such as foods high in sugar, protein, and fiber

- avoiding high-fat foods

Short bowel syndrome diet

Early nutritional support

Immediately after bowel surgery that results in short bowel syndrome, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is required until bowel function returns (bowel sounds are detected, and stool is produced). Depending on the severity of short bowel syndrome, full enteral/oral nutrition may be achieved in a matter of weeks to months, or may never be achieved. It is important that a patient be given as much enteral/oral nutrition as possible to facilitate bowel growth and increased absorption of nutrients, and to decrease the deleterious effects of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) on the liver 11.

Long term nutritional support

Nutrient Deficiencies

Once a child is on full enteral or oral feeds and parenteral nutrition has been discontinued, adequacy of micronutrient absorption becomes a concern. This is especially important when a significant portion of the ileum is missing. Ileal resection can result in fat and fat soluble vitamin malabsorption, consequently it is frequently necessary to give fat soluble vitamins in a water soluble form. These are available in individual vitamin preparations or in a multivitamin preparation (vitamin A, D, E and vitamin K), which contains water and fat soluble vitamins, all in a water soluble form. Additionally, patients with ileal resection may need vitamin B12 injections every 1 to 3 months. It can take from several months to several years for a vitamin B12 deficiency to develop; therefore, long term, regular monitoring of vitamin B12 status is necessary.

Trace minerals that may be malabsorbed include calcium (this is often due to vitamin D malabsorption), iron, magnesium, and zinc. These nutrients need to be monitored periodically, especially in the months just after parenteral nutrition is discontinued, and whenever a patient develops a prolonged diarrheal illness or has bacterial overgrowth.

Bacterial Overgrowth

Patients with short bowel syndrome often have poor intestinal motility and dilated segments of the small intestine. These factors plus absence of the ileocecal valve contribute to the development of bacterial overgrowth 12. Bacterial overgrowth is present when the bacteria in the small bowel exceed normal levels. Bacterial overgrowth results in malabsorption by causing inflammation of the bowel wall and deconjugation of bile acids (which results in rapid reabsorption of bile, leaving very little for fat absorption). Symptoms include very foul smelling stools and flatus, bloating, cramps, severe diarrhea, gastrointestinal blood loss, and accumulation of D-lactic acid in the blood. Bacterial overgrowth can be diagnosed by breath hydrogen test either fasting or after an oral glucose load, by aspiration and culture of small bowel contents or by blood test for D-lactic acid. Bacterial overgrowth is treated with oral antibiotics. In many cases it is necessary to give cyclic antibiotics for the first five days of every month. In some patients continuous antibiotics are necessary; in these cases, antibiotics are rotated every two to three months to avoid overgrowth of resistant bacteria 3.

Medications

A health care provider may prescribe medications to treat short bowel syndrome, including

- antibiotics to prevent bacterial overgrowth

- H2 blockers to treat too much gastric acid secretion

- proton pump inhibitors to treat too much gastric acid secretion

- choleretic agents to improve bile flow and prevent liver disease

- bile-salt binders to decrease diarrhea

- anti-secretin agents to reduce gastric acid in the intestine

- hypomotility agents to increase the time it takes food to travel through the intestines, leading to increased nutrient absorption

- growth hormones to improve intestinal absorption

- teduglutide to improve intestinal absorption

Surgery

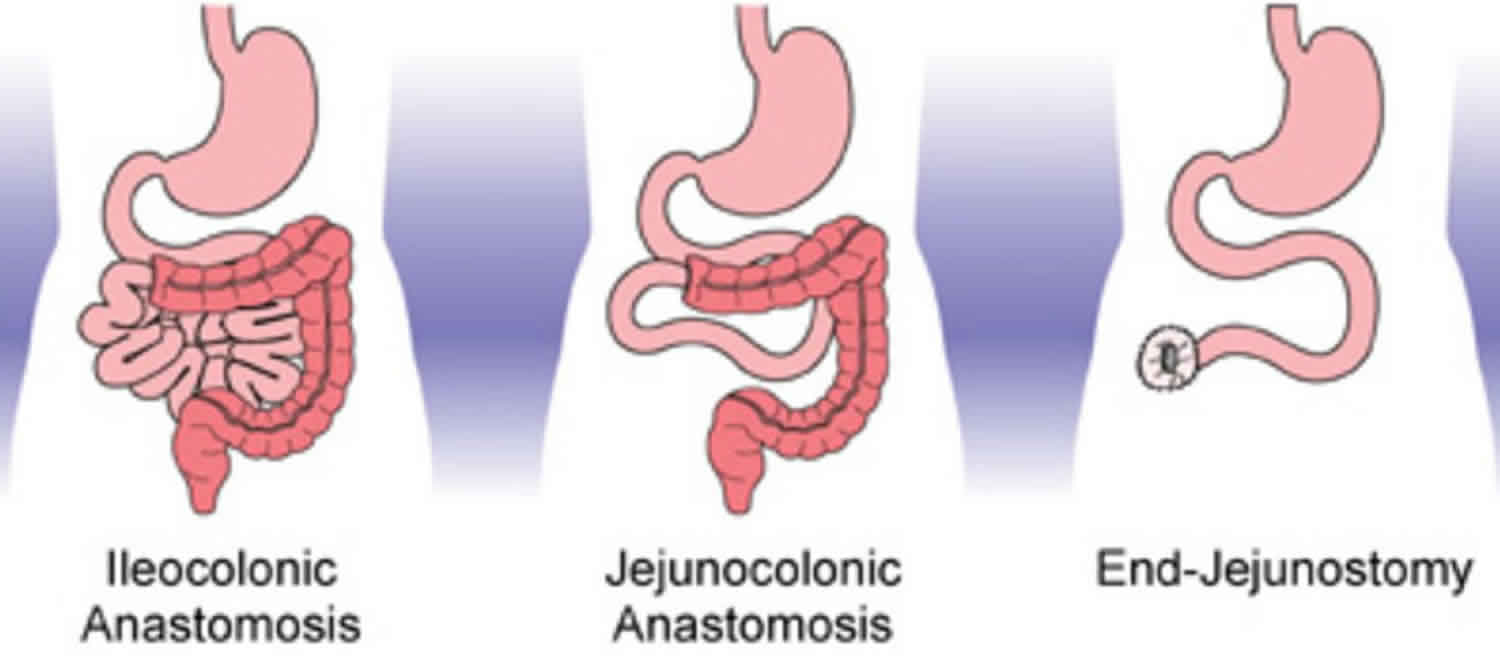

The goal of surgery is to increase the small intestine’s ability to absorb nutrients. Approximately half of the patients with short bowel syndrome need surgery.2 Surgery used to treat short bowel syndrome includes procedures that:

- prevent blockage and preserve the length of the small intestine

- narrow any dilated segment of the small intestine

- slow the time it takes for food to travel through the small intestine

- lengthen the small intestine

Long-term treatment and recovery, which for some may take years, depend in part on:

- what sections of the small intestine were removed

- how much of the intestine is damaged

- how well the muscles of the intestine work

- how well the remaining small intestine adapts over time

Intestinal transplant

An intestinal transplant is surgery to remove a diseased or an injured small intestine and replace it with a healthy small intestine from a person who has just died, called a donor. Sometimes a living donor can provide a segment of his or her small intestine.

Transplant surgeons—doctors who specialize in performing transplant surgery—perform the surgery on patients for whom other treatments have failed and who have life threatening complications from long-term parenteral nutrition. An intestinal-transplant team performs the surgery in a hospital. The patient will need anesthesia. Complications of intestinal transplantation include infections and rejection of the transplanted organ.

A successful intestinal transplant can be a life-saving treatment for people with intestinal failure caused by short bowel syndrome. By 2008, transplant surgeons had performed almost 2,000 intestinal transplantations in the United States—approximately 75 percent of which were in patients younger than 18 years of age 13.

A health care provider will tailor treatment to the severity of the patient’s disease:

- Treatment for mild short bowel syndrome involves eating small, frequent meals; drinking fluid; taking nutritional supplements; and using medications to treat diarrhea.

- Treatment for moderate short bowel syndrome is similar to that for mild short bowel syndrome, with the addition of parenteral nutrition as needed.

- Treatment for severe short bowel syndrome involves use of parenteral nutrition and oral rehydration solutions. Patients may receive enteral nutrition or continue normal eating, even though most of the nutrients are not absorbed. Both enteral nutrition and normal eating stimulate the remaining intestine to work better and may allow patients to discontinue parenteral nutrition. Some patients with severe short bowel syndrome require parenteral nutrition indefinitely or surgery.

Long-Term Monitoring

Patients with short-bowel syndrome require lifetime follow-up. Those on parenteral nutrition require frequent monitoring of serum chemistries; liver function tests; and vitamin, mineral, and trace element levels 14. Patients should be weighed regularly after resolution of postoperative fluid flux to ensure that they are not losing weight on their nutritional regimen. Nitrogen balance studies can be performed but are cumbersome because of the need for 12- to 24-hour urine collection. Patients on specialized enteral nutrition can be monitored similarly.

Patients who have had nontransplant operations are monitored to assure that proper wound healing and bowel function are occurring. In addition, several of the measures described above can be applied to their postoperative care. It is important to confirm that these patients can ingest and absorb adequate amounts of protein and calories.

Patients who receive single or multiple organ transplants are monitored, and their cases are followed closely. The most dreaded postoperative complications that must be identified early include organ rejection, opportunistic infection, and development of immunosuppression-related malignancies. These patients may be monitored by all the measures mentioned above. In addition, immunosuppressant drug levels can be monitored.

The physician usually diagnoses acute rejection by endoscopically guided mucosal biopsies, and chronic rejection is diagnosed definitively by complete examination of resected grafts.

Transplant patients must also be monitored for evidence of graft-versus-host disease. Typically affected areas include the skin, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and lungs.

Short bowel syndrome prognosis

At present, there is no reliable cure for short-bowel syndrome. In newborn infants, the 4-year survival rate on parenteral nutrition is approximately 70%. In newborn infants with less than 10% of expected intestinal length, 5-year survival is approximately 20% 15. People with short bowel syndrome can lead a productive, lengthy, and happy life if their condition is managed appropriately 16. Predictors of the overall long term prognosis of children with small bowel syndrome is influenced by the size and location of the resected intestine (i.e., whether it involves the ileocecal valve, duodenum, jejunum, or ileum) 2 and the development of liver disease (e.g., cholestasis) 15. The most common cause of death in these patients is liver failure.

Initially, all people with short bowel syndrome require total parenteral nutrition (TPN). The goal of treatment is to gradually decrease the requirement for total parenteral nutrition and at best, to eliminate its need. Data from Howard et al 17 and Ladefoged et al 18 revealed that the 4-year survival rate in patients who depend on parenteral nutrition is about 70%.

Some children with short bowel syndrome are able to eat by mouth and digest food in a matter of weeks to months 2 (optimal adaption of the intestine may evolve over the course of 1 to 2 years) 16. Your child’s physician should counsel you regarding your child’s nutritional status, treatment, and goals. Once children are able to eat, their doctor will likely recommend some modifications to their diet, and possibly vitamin and other nutrient supplementations.

Children who are off of parenteral nutrition support still remain at risk for dehydration, bacterial overgrowth, and nutritional deficiencies. As a result they require long-term, regular monitoring. Symptoms of gastroenteritis should be reported to their doctors right away. Regular treatment with antibiotics to treat/prevent infections is often required 2.

Despite careful treatment, some children with short bowel syndrome have very poor digestion and are unable to get adequate nutrients from diet alone. These children require long term total parenteral nutrition. In addition to the risks described above (i.e., dehydration, bacterial overgrowth, nutritional deficiencies), there are a number of additional challenges that can occur with long term total parenteral nutrition use (e.g., catheter infection, liver disease).

Nontransplant surgical procedures have been applied to short-bowel syndrome. Early results were mixed, but many of the procedures being performed then involved segment reversal. Subsequent series have demonstrated clinical improvement in more than 80% of patients. The most common operations performed in these series were intestinal tapering, intestinal lengthening, and strictureplasty. Even in these series, segment reversal and creation of artificial valves produced dubious results.

Organ transplantation is a promising therapeutic option but continues to be fraught with problems. Early postoperative mortality can be as high as 30%. Data from leading transplant centers have shown that the 1-year survival rates can be as high as 80-90%, and approximately 60% of patients are alive at 4 years.

References- Thompson JS, Rochling FA, Weseman RA, Mercer DF. Current management of short bowel syndrome. Current Problems in Surgery. 2012;49(2):52–115.

- Short Bowel Syndrome. http://depts.washington.edu/growing/Assess/SBS.htm

- Vanderhoof, JA, Langnas, AN, Pinch, LW, Thompson, JS, Kaufman, SS. Short bowel syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 14:359-370, 1992.

- Thompson JS, Rochling FA, Weseman RA, Mercer DF. Current management of short bowel syndrome. Current Problems in Surgery. 2012;49(2):52–115.

- Short-Bowel Syndrome. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/193391-overview

- Wilmore DW, Byrne TA, Persinger RL. Short bowel syndrome: new therapeutic approaches. Curr Probl Surg. 1997 May. 34 (5):389-444.

- Byrne TA, Persinger RL, Young LS, Ziegler TR, Wilmore DW. A new treatment for patients with short-bowel syndrome. Growth hormone, glutamine, and a modified diet. Ann Surg. 1995 Sep. 222 (3):243-54; discussion 254-5.

- Vanderhoof JA, Langnas AN. Short-bowel syndrome in children and adults. Gastroenterology. 1997 Nov. 113(5):1767-78.

- Puder M, Valim C, Meisel JA, Le HD, de Meijer VE, Robinson EM, et al. Parenteral fish oil improves outcomes in patients with parenteral nutrition-associated liver injury. Ann Surg. 2009 Sep. 250 (3):395-402.

- Moreno JM, Planas M, Lecha M, Virgili N, Gómez-Enterría P, Ordóñez J, et al. [The year 2002 national register on home-based parenteral nutrition]. Nutr Hosp. 2005 Jul-Aug. 20 (4):249-53.

- Freund, HR. Abnormalities of liver function and hepatic damage associated with total parenteral nutrition. Nutrition, 7:1-6, 1991.

- Stringer, MD, & Puntis, JW. Short bowel syndrome. Archives of Diseases of Childhood, 73:170-3, 1995.

- Mazariegos GV, Steffick DE, Horslen S, et al. Intestine transplantation in the United States, 1999–2008. American Journal of Transplantation. 2010;10(4):1020–1034.

- Fitzgibbons S, Ching YA, Valim C, Zhou J, Iglesias J, Duggan C, et al. Relationship between serum citrulline levels and progression to parenteral nutrition independence in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2009 May. 44 (5):928-32.

- Spencer AU, Neaga A, West B, et al. Pediatric short bowel syndrome: redefining predictors of success. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):403–412. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000179647.24046.03 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1357748

- Buchman AL, Scholapio J, Fryer J. AGA Technical Review on Short Bowel Syndrome and Intestinal Transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2003

- Howard L, Ament M, Fleming CR, Shike M, Steiger E. Current use and clinical outcome of home parenteral and enteral nutrition therapies in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1995 Aug. 109 (2):355-65.

- Ladefoged K, Hessov I, Jarnum S. Nutrition in short-bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996. 216:122-31.