Lucid interval

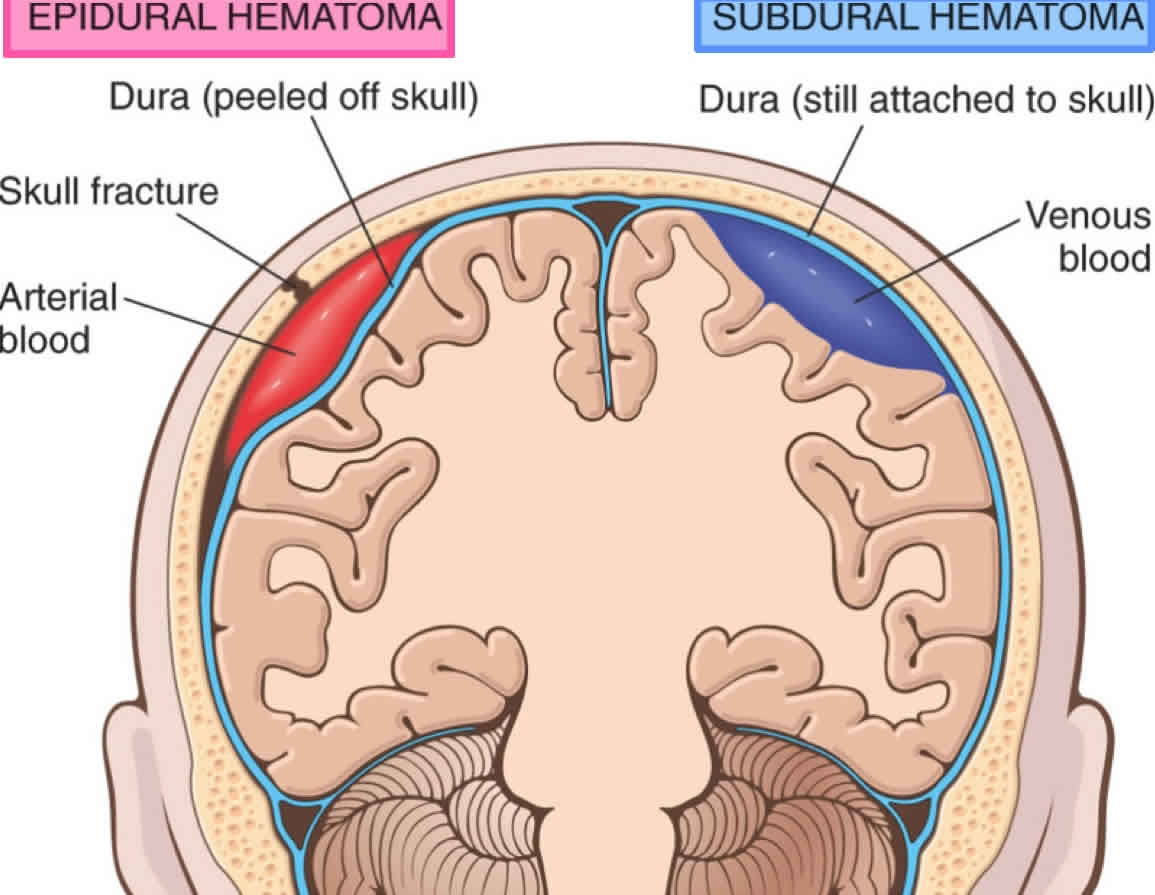

Lucid interval seen in head injury is defined as a transient period of consciousness after the initial loss of consciousness due to the primary brain injury or traumatic brain injury, after which the condition deteriorates rapidly due to blood accumulation due from subdural or epidural hematomas (‘peridural hematomas’), contusions/intracerebral hematomas and brain swelling, which may cause headache, vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, aphasia, seizures and hemiparesis. The lucid interval lasts for minutes to hours for most peridural hematomas and up to a couple of days for expanding intracerebral hematomas and brain swelling 1. A lucid interval is especially indicative of an subdural or epidural hematomas (‘peridural hematomas’) which is a collection of blood within the potential space between the outer layer of the dura mater and the inner table of the skull 2. Lucid interval occurs in 14% to 21% of patients with an epidural hematoma 2. However, these patients may be unconscious from the beginning or may regain consciousness after a brief coma or may have no loss of consciousness 2. Therefore, the presentations range from a temporary loss of consciousness to a coma. Beware that the lucid interval is not pathognomonic for an epidural hematoma and may occur in patients who sustain other expanding mass lesions. The classic lucid interval occurs in pure epidural hematomas that are very large and demonstrate a CT scan finding of active bleeding. The presentation of symptoms depends on how quickly the epidural hematoma is developing within the cranial vault. A patient with a small epidural hematoma may be asymptomatic, but this is rare. Also, an epidural hematoma may also develop in a delayed fashion.

A posterior fossa epidural hematoma is a rare event. This kind of epidural hematoma may account for approximately 5% of all posttraumatic intracranial mass lesions. Patients with posterior fossa epidural hematoma may remain conscious until late in the evolution of the hematoma, when they may suddenly lose consciousness, become apneic, and die. These lesions often extend into the supratentorial compartment by stripping the dura over the transverse sinus, resulting in a significant amount of intracranial bleeding.

This enlarging hematoma leads to eventual elevation of intracranial pressure (ICP) which may be detected in a clinical setting by observing ipsilateral pupil dilation (secondary to uncal herniation and oculomotor nerve compression), the presence of hypertension or widened pulse pressure (increasing systolic, decreasing diastolic), slowed heart rate (bradycardia) and irregular breathing 3. This triad is known as the “Cushing reflex” or Cushing’s triad 3. These findings may indicate the need for immediate intracranial intervention to prevent central nervous system (CNS) depression and death.

Cushing triad, as a result of the Cushing reflex, is typically observed in the later stages of acute head injury. Although the reflex is a homeostatic response by the body in an attempt to rescue under-perfused brain tissues, the Cushing triad is, unfortunately, a late sign of increasing ICP, and indicative that brainstem herniation is imminent 3. Patients who present to the emergency department with concerns for increased ICP and two of three signs of the Cushing reflex have been found to have almost two-fold higher mortality than patients with normal and stable vital signs. It is, therefore, important to recognize early signs of elevated ICP (e.g., a headache, nausea, vomiting, altered level of consciousness) to intervene as early as possible 4. Many clinicians use the presence of bradycardia and hypertension as an indication of increased ICP, however, this signals a late-stage Cushing reflex that carries a poor prognosis for the patient. Moving into the future, it may be wise to look for the presence of tachycardia and hypertension in patients with suspected intracranial pathology so that interventions can start promptly 5.

Cushing reflex is most usually an irreversible condition with a terminal prognosis for the patient. Initial emergency treatments are aimed at rapidly lowering the ICP and include: Elevation of the patient’s head 30 to 45 degrees, mannitol and/or furosemide, which act as an osmotic diuretic, induced hyperventilation, steroids, or cerebrospinal fluid drainage 6.

Lucid intervals may also occur in conditions other than traumatic brain injury, such as heat stroke 7 and the postictal phase after a seizure in epileptic patients 8.

Epidural hematoma is a neurosurgical emergency. Epidural hematoma requires urgent surgical evacuation to prevent irreversible neurological injury and death secondary to hematoma expansion and herniation. Neurosurgical consultation should be urgently obtained as it is important to intervene within 1 to 2 hours of presentation 9.

The priority is to stabilize the patient, including the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation), and these should be addressed urgently.

Surgical intervention is recommended in patients with:

- Acute epidural hematoma

- Hematoma volume greater than 30 ml regardless of Glasgow coma scale score (GCS)

- GCS less than 9 with pupillary abnormalities like anisocoria

Operative management

In patients with acute and symptomatic epidural hematomas, the treatment is craniotomy and hematoma evacuation. Based on the available literature, “trephination” or burr hole evacuation is often a crucial form of intervention if more advanced surgical expertise is unavailable; it may even decrease mortality. However, the performance of a craniotomy, if feasible, can provide a more thorough evacuation of the hematoma.

Non-operative management

There is a scarcity of literature comparing conservative management with surgical intervention in patients with epidural hematoma. However, a non-surgical approach may be considered in a patient with acute epidural hematoma who has mild symptoms and meets all of the criteria listed below:

- Epidural hematoma volume of less than 30 ml

- Clot diameter of less than 15 mm

- Midline shift of less than 5 mm

- GCS greater than 8 and on physical examination, shows no focal neurological symptoms.

If the decision is made to manage acute epidural hematoma non-surgically, close observation with repeated neurological examinations and continuous surveillance with brain imaging is required, as the risk for hematoma expansion and clinical deterioration is present. The recommendation is to obtain a follow-up head CT scan within 6 to 8 hours following brain injury.

References- Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine, Reference Work 2nd Edition, 2016 ISBN 978-0-12-800055-7

- Khairat A, Waseem M. Epidural Hematoma. [Updated 2020 Jul 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518982

- Dinallo S, Waseem M. Cushing Reflex. [Updated 2020 May 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549801

- Bhandarkar P, Munivenkatappa A, Roy N, Kumar V, Samudrala VD, Kamble J, Agrawal A. On-admission blood pressure and pulse rate in trauma patients and their correlation with mortality: Cushing’s phenomenon revisited. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2017 Jan-Mar;7(1):14-17.

- Kalmar AF, Van Aken J, Caemaert J, Mortier EP, Struys MM. Value of Cushing reflex as warning sign for brain ischaemia during neuroendoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 2005 Jun;94(6):791-9.

- Aronovich D, Scumpia A, Edwards D. Cushing’s reflex in a rare case of adult medulloblastoma. World J Emerg Med. 2014;5(2):148-50.

- Casa DJ, Armstrong LE, Ganio MS, Yeargin SW. Exertional heat stroke in competitive athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2005;4(6):309-317. doi:10.1097/01.csmr.0000306292.64954.da

- Nishida T, Kudo T, Nakamura F, Yoshimura M, Matsuda K, Yagi K. Postictal mania associated with frontal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6(1):102-110. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.11.009

- Gutowski P, Meier U, Rohde V, Lemcke J, von der Brelie C. Clinical Outcome of Epidural Hematoma Treated Surgically in the Era of Modern Resuscitation and Trauma Care. World Neurosurg. 2018 Oct;118:e166-e174.