Lumbar facet syndrome

Lumbar facet syndrome also called lumbosacral facet syndrome, refers to a clinical condition consisting of various patient-reported symptoms, including mechanical back pain, radicular symptoms, and neurogenic claudication, secondary to either acute or subacute trauma, or secondary to the degenerative cascade affecting the posterior spinal elements 1. The facet joints commonly called zygapophyseal joints or zygapophysial joints (Z-joints), degenerate secondary to repetitive overuse and everyday activities that can eventually lead to microinstability and synovial facet cysts that generate and compress the surrounding nerve roots 2.

The term facet joint is a misnomer because the joint occurs between adjoining zygapophyseal processes, rather than facets, which are the articular cartilage lining small joints in the body (eg, phalanges, costotransverse and costovertebral joints). This joint is also sometimes referred to as the apophyseal joint or the posterior intervertebral joint.

Lumbar spine anatomy

Your spine is made up of 24 small rectangular-shaped bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

The five vertebrae in the lower back comprise the lumbar spine.

Each individual vertebra has unique features depending on the region in which it is found. Every vertebra, regardless of location, has three basic functional parts: (1) the drum-shaped vertebral body, designed to bear weight and withstand compression or loading; (2) the posterior (backside) arch, made of the lamina, pedicles and facet joints; and (3) the transverse processes, to which muscles attach.

Other parts of your spine include:

Spinal cord and nerves

These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

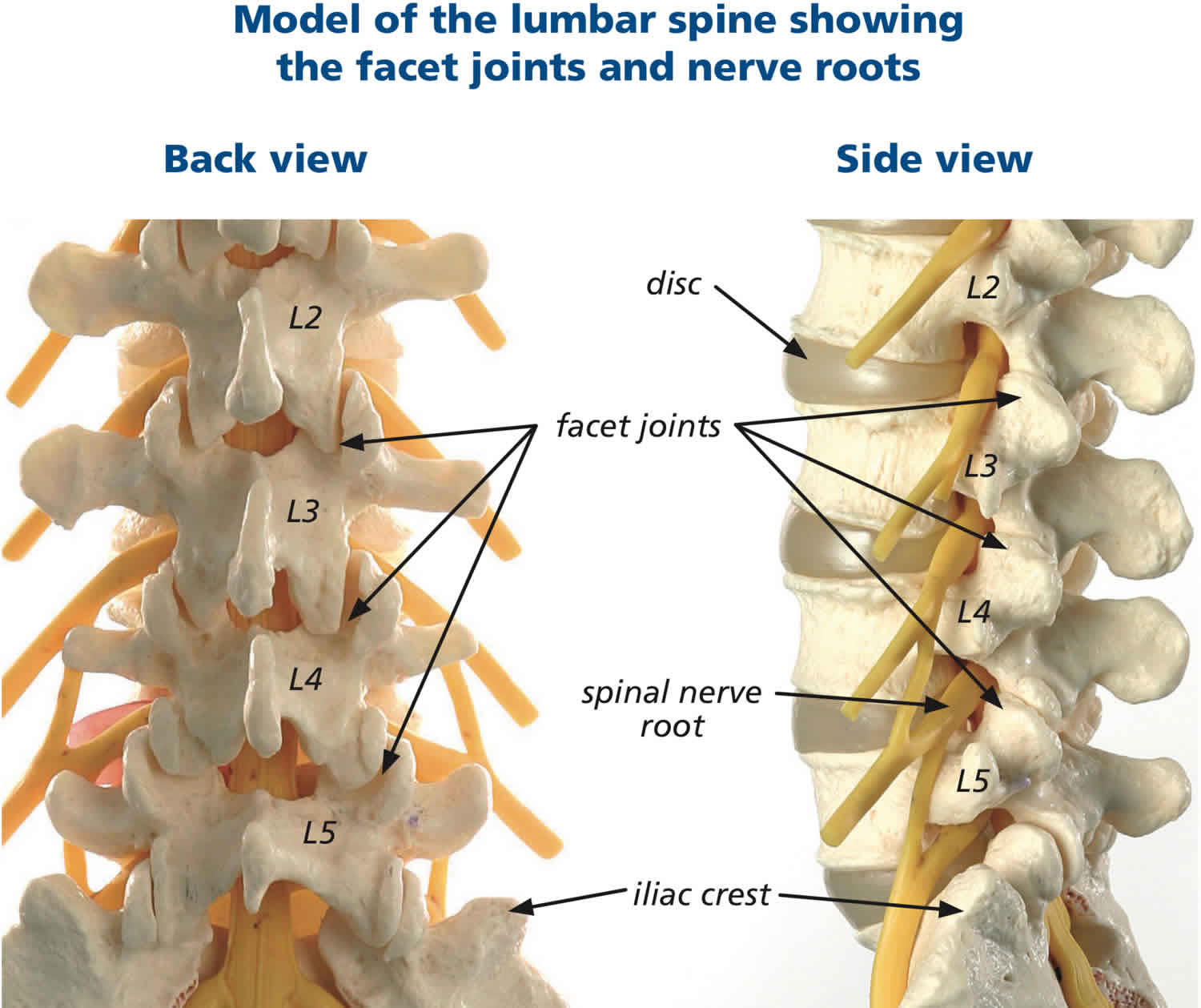

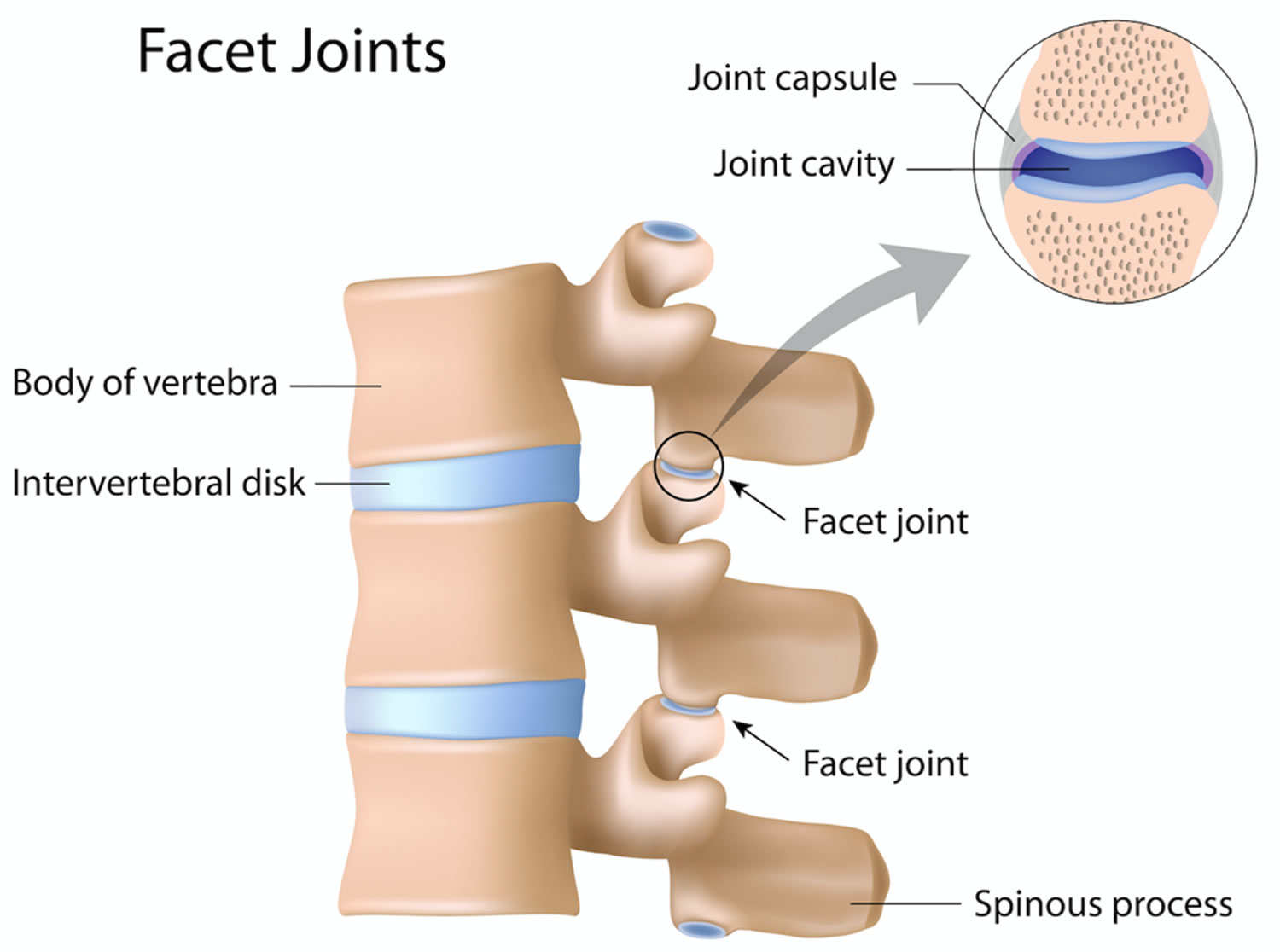

Facet joints

Between the back of the vertebrae are small joints that provide stability and help to control the movement of the spine. The facet joints work like hinges and run in pairs down the length of the spine on each side.

The lumbar facets are composed of the inferior articular process of the vertebra above and the superior articular process of the vertebra below. The zygapophyseal joints serve to stabilize the spine and prevent injury by limiting the spinal range of motion. The facet joints are true synovial joints. The articular surface is contained in a cartilaginous sheath over an encapsulated fibrous capsule. Like other cartilaginous joints, the lumbar facets are prone to degradation over time and can cause chronic low back pain when irritated. The sensory innervation of the facet is supplied by the medial branch of the posterior rami of the spinal nerve at the level of, and the level above, the facet joint. For example, The L3-L4 medial branch receives innervation from the L2 and L3 medial branch nerves. Noxious stimulation of the medial branches is caused by degenerative changes in the facet joint, which results in facet pain and lumbosacral facet syndrome 3.

Intervertebral disks

In between the vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. Intervertebral disks cushion the vertebrae and act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

The vertebral body

The vertebral body is composed of hard cortical bone on the outside and less dense cancellous bone on the inside. The top and bottom of the vertebral body are called the end plates. The intervertebral disc, sandwiched between two vertebral bodies, is attached to the end plates. Changes in the disc may be accompanied by changes in the end plates.

The pedicle is a paired, strong, tubular bony structure made of hard cortical bone on the outside and cancellous bone on the inside. Each pedicle comes out of the side of the vertebral body and projects to the back. Pedicles act as the lateral (side) walls of the bony spinal canal that protects the spinal cord and cauda equina, or nerve roots, in the lumbar region. There is also a space created between the facet joints and pedicles of one vertebral body and the next, called the intervertebral foramen, through which the spinal nerves branch out to the rest of your body.

The lamina are shingle-like plates of bone coming from the pedicles to arch over the nerves and join at the midline. The lamina are shorter than the vertebral bodies so that there is a gap between any two laminae, bridged by soft tissue called the ligamentum flavum. This provides additional protection for the nerves that lie underneath it. Together, the lamina and pedicles form the vertebral arch.

As the lamina come together at the back of the spinal column, they join to form the spinous process, the bony part of the spine that you can feel at the midline when you rub your back. There is an interspinous ligament that runs between the spinous processes of the vertebrae and a supraspinous ligament that runs on top of them from the cervical region to the sacrum.

Each vertebral body has two articular processes at the top and bottom where the lamina and pedicle meet. These articular processes create a joint, called the facet joint, between the stacked vertebral bodies. There is a facet joint on each side of the vertebral body. The facet joint typically lies behind the spinal nerves as they emerge from the central spinal canal. The surfaces of the facet joint are capped with cartilage and the joint is contained in a capsule lined by synovium, much like the knee joint. The two facet joints and the intervertebral disc at each level allow for motion between the vertebral bodies.

The typical vertebral body has two transverse processes, or lateral projections, one on each side. These projections serve as points of attachment for muscles and ligaments in the spine. In the cervical spine, the transverse processes each have a foramen or canal through which the vertebral artery and vein travel. The intertransverse ligaments connect the transverse processes of the vertebrae on each side of the spinal column.

In the lumbar spine, identification of the pars interartcularis is important because it is the site of pathology related to spondylolisthesis, or “slipped vertebra.” This is another paired structure on the back side of the spine and it links the pedicle, transverse process, lamina and articular facets on each side of the vertebrae.

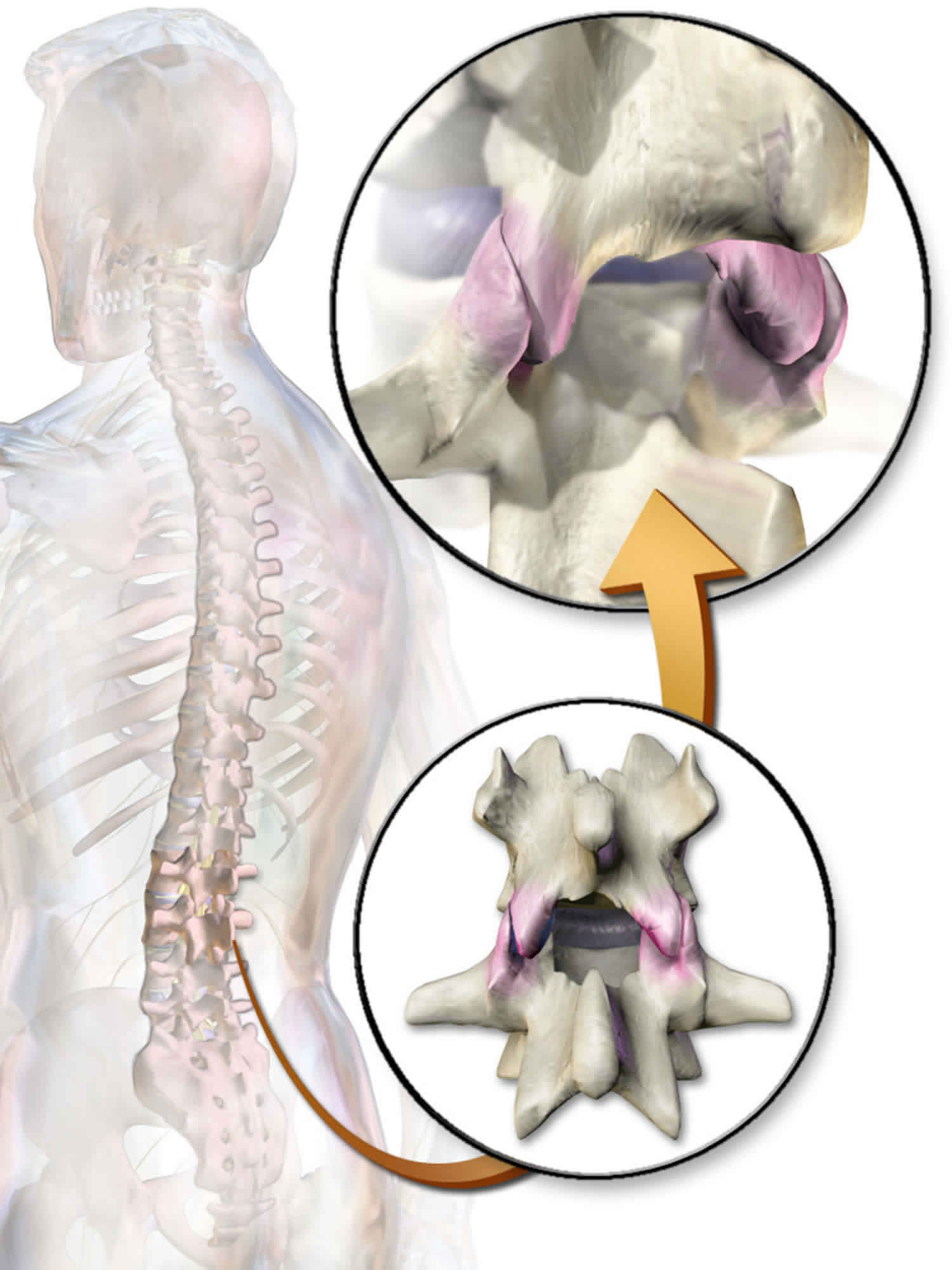

Figure 1. Lumbar vertrebrum (looking from above)

Figure 2. Lumbar vertebrae anatomy (looking from behind and from the side)

Figure 3. Lumbar spine facet joints

Lumbar facet syndrome causes

Lumbosacral facet syndrome can occur secondary to repetitive overuse and microtrauma, spinal strains and torsional forces, poor body mechanics, obesity, and intervertebral disk degeneration over the years. This notion is supported by the strong association between the incidence of facet arthropathy and increasing age 4.

In some instances, an inciting event such as trauma or whiplash injury can be identified, although trauma patients tend to develop cervical facet arthropathy more commonly than lumbosacral facet syndrome. The role of trauma remains controversial in the literature. The irritation of the degenerative zygapophyseal joint over time leads to inflammation, which is perceived as low back pain.

Lumbar facet syndrome symptoms

Establishing a diagnosis of lumbosacral facet syndrome is difficult because the findings are nonspecific and correlation between the history and physical examination findings is poor. However, obtaining a detailed history and performing a physical examination help rule out other entities and assist with guiding the examiner in establishing the diagnosis of lumbosacral facet joint mediated low back pain.

Although no single sign or symptom is diagnostic, Jackson et al 5 demonstrated that the combination of the following 7 factors was significantly correlated with pain relief from an intra-articular Z-joint injection:

- Older age

- Previous history of low back pain

- Normal gait

- Maximal pain with extension from a fully flexed position

- The absence of leg pain

- The absence of muscle spasm

- The absence of exacerbation with a Valsalva maneuver

Because most lumbosacral facet joint pain is related to degenerative changes, older age may be related to facet-joint pathology.

The basic history should include a temporal account of the symptoms, a complete description of the problem, and a discussion of the associated activities that cause or alleviate the pain. The patient should describe the location of the pain; state whether it is isolated or radiating; and relate its intensity, character, and frequency. Red flags (ie, symptoms or signs that stand out as highly suggestive) that should be seriously scrutinized include the presence of unexplained weight loss, fever, and chills. The clinician should also obtain a history of any previous treatments (eg, injections, medications, therapy) and whether they were successful.

Lumbosacral facet joint pathology should be considered if the patient describes nonspecific low back pain with a deep and achy quality that is usually localized to a unilateral or bilateral paravertebral area.

Provocative injections of the facet-joints have been used to create a sclerotomal map of the facet-joint’s pain referral pattern. Based on these studies, the common referral areas for facet-joint–mediated pain are flank pain, buttock pain (often extending into the posterior thigh, but rarely below the knee), pain overlying the iliac crests, and pain radiating into the groin. However, this pain pattern is not consistently reported in patients with facet-joint pain as confirmed by diagnostic intra-articular facet-joint injections. Therefore, this sclerotomal representation of the facet-joint is only suggestive, not diagnostic.

The pain is often exacerbated by twisting the back, by stretching, by lateral bending, and in the presence of a torsional load. Some patients describe their pain as worse in the morning, aggravated by rest and hyperextension, and relieved by repeated motion. Often, this lumbosacral facet syndrome may occur after an acute injury (eg, extension and rotation of the spine), or it may be chronic in nature.

Unlike other lumbar spine pathologies such as disc herniation, facet-joint–mediated pain likely will not worsen with an increase in intra-abdominal and thoracic pressure. Therefore, worsening of pain with coughing, laughing, or a Valsalva maneuver is suggestive that the Z-joint is not the primary pain generator.

Historically, lumbosacral facet loading during a physical exam has been used to diagnose lumbosacral facet pain. This maneuver is performed by having the patient extend and rotate the spine. This serves to increase pressure on the facet joints thus eliciting a pain response. However, studies have shown that facet loading is unreliable in diagnosing facetogenic pain. Additionally, paraspinal muscle tenderness has been shown to be weakly associated with facetogenic pain, although this finding is considered to be non-specific 6.

Lumbosacral facet syndrome complications

In some cases, lumbosacral facet syndrome can lead to chronic pain, time lost from employment or sports, and disability. Interventional procedures, such as facet joint injections with anesthetics and corticosteroids, can lead to transient lower-extremity weakness, insomnia, headache, fluid and electrolyte disorders (especially in patients with congestive heart failure), gastrointestinal upset, bone demineralization, and impaired glucose tolerance (patients with diabetes). Less common effects are mood swings, increased appetite, and, the most serious, adrenocortical insufficiency. Dural puncture can lead to infection and an increased incidence of headaches.

Lumbar facet syndrome diagnosis

Physical examination can be useful in ruling out other causes of chronic low back pain; however, studies have shown that physical exam is relatively nonspecific.

Plain radiographs. Plain radiographs are traditionally ordered as the initial step in the workup of lumbar spine pain. The main purpose of plain films is to determine underlying structural pathologic conditions. These studies are not generally recommended in the first month of symptoms in the absence of red flags. An exception to this would be if the low back symptoms are related to a sports injury and a fracture is suggested. Degenerative changes in the facet joints can be visualized in radiologic studies.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning. Generally, CT scanning is not necessary unless other bony pathology (eg, fracture) must be excluded. In patients with chronic low back pain, degenerative changes on CT scan are cited to range from 40% to 85%. Studies have shown MRI to be more than 90% sensitive and specific in visualizing facet degeneration.

Medial branch block

Due to the poor correlation between history, physical exam, and lumbosacral facet syndrome, diagnostic blocks are considered to be the mainstay in establishing a diagnosis. Fluoroscopically guided medial branch nerve injections are often used for diagnostic purposes to determine whether the facet-joint in question is responsible for low back pain. Given the dual innervation of each facet-joint, one must anesthetize or block the cephalad and subadjacent medial branches (eg, anesthetize the L3 and L4 medial branches for the L4-L5 facet-joint). Of note, false positive results have been documented to be as high as 25% to 40% in the lumbar spine. Because of this, it is recommended that two diagnostic medial branch blocks are performed to confirm a diagnosis. A positive response is considered to be greater than 80% pain relief post-procedure 7.

Single injections with a local anesthetic have high false-positive rates (38%). Therefore, when performing any interventional injection, the criterion standard is to use a double- or triple-block paradigm. In a double-block protocol, the patient is given an injection with a short-acting anesthetic (eg, lidocaine) and records the duration of pain relief in a diary. On a follow-up visit (typically 1-2 week later), a second injection is performed, using an anesthetic with a different duration of action (eg, bupivacaine, which has a longer half-life than lidocaine), and the patient again should chart pain relief in a diary. A patient is diagnosed as having a positive block if they receive pain relief (typically >80%) for both injections for a length of time corresponding to the duration of action of the medication.

For additional diagnostic accuracy, a third block can be performed with saline, although this is rarely performed in clinical practice. The diagnostic reliability of double- and triple-block protocols is clearly superior to that of a single-block protocol; therefore, these should be used before performing an ablation procedure or surgery.

Intra-articular facet joint injection with corticosteroids and a local anesthetic can also be performed 8. Typically, this is performed under fluoroscopic guidance with contrast medium. Intra-articular anesthetic injections are considered the most accurate method for diagnosing facet joint–mediated pain, particularly when performed with a double- or triple-block protocol.

Lumbar facet syndrome treatment

The initial treatment plan for acute facet joint pain is focused on education, relative rest, pain relief, maintenance of positions that provide comfort, exercises, and some modalities. Physical therapy includes instruction on proper posture and body mechanics in activities of daily living that protect the injured joints, reduce symptoms, and prevent further injury. Positions that cause pain (eg, extension, oblique extension) should be avoided. Bed rest beyond 2 days is not recommended because this can have detrimental effects on bone, connective tissue, muscle, and the cardiovascular system. Thus, activity modification, rather than bed rest, is strongly recommended.

Modalities such as superficial heat and cryotherapy may also help relax the muscles and reduce pain. In addition, medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may also be administered. Spinal manipulation and mobilization may also be attempted to reduce pain.

Spinal manipulation is being used for both short- and long-term pain relief. Some evidence supports the use of spinal manipulative therapy combined with a trunk-strengthening program, which, over the course of a year, may actually reduce the need for pain medication.

Nonoperative treatment

Nonoperative management includes oral medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and oral steroids during acute flares. Additionally, weight loss and physical therapy have demonstrated successful outcomes 9.

More invasive nonoperative modalities that can be considered include a CT-guided aspiration. The literature is controversial with respect to the overall effectiveness of this modality. Patients should also be counseled regarding the risk of facet cyst recurrence and return of symptoms even after the aspiration is performed.

Surgical treatment

Indications for surgical intervention include:

- Symptoms refractory to nonoperative modalities (e.g. 3 to 6 month trial)

- Large associated synovial facet cyst correlating with clinical exam and presentation

Laminectomy with decompression is the classic first line treatment for symptomatic, intraspinal synovial cysts

The literature also supports the utilization of facetectomy, decompression, and instrumented fusion (as opposed to a simple “lami decompression”)

Minimally invasive techniques

Other management modalities include facet injections, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the medial branch nerves 10. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy is a method of denaturing the nerves that innervate the facet joint through coagulation, thus resulting in more prolonged pain relief 11. Medial branch neurotomy through radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has emerged as the standard therapy for facet-mediated low back pain 12. When performing these procedures, remember that the radiofrequency signal spreads circumferentially from the shaft and not linearly from the tip of the transducer; therefore, the shaft of the transducer must be placed parallel to the medial branch (as opposed to when performing a medial branch block, in which the tip should be aimed at the medial branch because the anesthetic leaves the tip of the needle and not the shaft). Once the axons regenerate, pain often returns.

The therapeutic benefit of this procedure likewise remains controversial 13; however, success rates range from 17-90% for periods of 6-12 months. Many of the studies have poor selection criteria, inconsistent techniques, poor outcome measures, and small sample sizes.

An alternative to medial branch block denervation was studied by Iwatsuki et al 14 in 21 patients with lumbosacral facet syndrome. These investigators evaluated the use of laser denervation to the dorsal surface of the facet capsule. At 1-year postprocedure, 17 patients (81%) experienced complete or greater than 70% pain reduction, whereas 4 patients (19%) had unsuccessful therapy. Iwatsuki et al 14 suggested that the dorsal surface of the facet capsule might be a more preferable target for facet denervation.

Other treatment options

Spinal manipulation may be useful for both short- and long-term pain relief. Some evidence supports the use of spinal manipulative therapy combined with a trunk-strengthening program, which, over the course of a year, may actually reduce the need for pain medication.

While radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of general low back pain is controversial, one area that it seems to have better outcomes is lumbar facet syndrome. A study that investigated function, pain, and medication use outcomes of radiofrequency ablation for lumbar facet syndrome demonstrated a durable treatment effect of radiofrequency ablation for lumbar facet syndrome at long-term follow-up, as measured by improvement in function, pain, and analgesic use 15.

A study by Juch et al 16 reviewed three randomized clinical trials that evaluated the effectiveness of radiofrequency denervation in 681 total patients with chronic low back pain and who were unresponsive to standard treatment (251 patients in the facet joint trial, 228 in the sacroiliac joint trial and 202 patients in a combination of facet joints, sacroiliac joints, or intervertebral disks trial). The study reported no clinically important improvements in patients from radiofrequency denervation combined with a standardized exercise program compared with a standardized exercise program alone 16.

Lumbar facet syndrome exercises

Once the painful symptoms are controlled during the acute phase of treatment, stretching and strengthening exercises of the lumbar spine and associated muscles can be initiated.

Because facet joint–mediated pain tends to be worse with extension, strengthening and conditioning exercises should typically be performed with a flexed trunk. Strengthening maneuvers must emphasize flexion, neutral postures, and pelvic tilt, all in an effort to reduce compression of the facet joints.

Another therapeutic goal is to reduce the lumbar lordosis because excessive lordosis increases the loading on the posterior elements, including the facet joints. Therefore, the patient should be taught pelvic tilt maneuvers to reduce the degree of lumbar lordosis. Pelvic tilt maneuvers can be taught in multiple positions (with knees bent while standing, legs straight while standing, and while sitting) to emphasize proper posture in multiple planes. Flexion-based exercises should be avoided in the presence of hypermobility or instability or if the maneuvers increase low back pain.

Similarly, stretching exercises should be focused on restoring proper pelvic tilt; therefore, special emphasis should be placed on stretching those muscles that cause excessive anterior pelvic tilt (eg, the hip flexors and lumbar extensors). Stretching should be not limited to just these muscles because all the muscles attaching to the lumbar spine and pelvic girdle may be in imbalance, and regular stretching can help restore normal motion to the lumbar spine and pelvis. Therefore, stretching programs should also include stretches of the hamstrings, quadriceps, hip abductors, gluteals, and abdominals. Stretching through dynamic postural motions (eg, yoga postures) can be especially helpful because the motions can restore balance to the muscles of the lumbar spine and pelvic girdle.

These exercises are eventually incorporated into a more comprehensive rehabilitation program, which includes spine stabilization exercises. The goal with these exercises is to teach the patient how to find and maintain a neutral spine during everyday activities. The neutral spine position is specific to the individual and is determined by the pelvic and spine posture that places the least stress on the elements of the spine and supporting structures. Bridges and planks are ideal exercises for this as they can be done in the neutral spine position with high muscle activation and relatively low spinal loads. McGill recommends work up to 1 rep at 60 sec holds to build the necessary endurance for optimum spine function. [23]

Dynamic lumbar control is also incorporated to protect the spine from biomechanical stresses, including tension, compression, torsion, and shear. Spinal stabilization emphasizes synergistic activation of the trunk and spinal musculature in the midrange position by strengthening the abdominal and gluteal muscles and enables the patient to develop the muscles that support the trunk and spine and, ultimately, diminish the overall stress on the spine.

Not all patients have the same flexibility and strength imbalances. Individual, detailed assessment by an experienced physical therapist may allow for a tailored therapeutic program.

Return to play

Athletes who demonstrate lumbosacral facet joint pathology should remain out of their sport until they regain full, pain-free range of motion and are able to complete sport-specific training without discomfort. They should also have symmetrical flexibility and be able to maintain trunk control throughout sporting activities to prevent recurrence.

Lumbosacral facet syndrome prognosis

With an active and focused spine rehabilitation program, the prognosis for these patients to achieve pain-free activity is good; however, the definitive diagnosis of facet joint pathology is often difficult to make and challenging to confirm. For some patients, low back pain may persist, and more aggressive interventions beyond conservative rehabilitation should be considered. Interventions such as medial branch blocks or neurolysis remain controversial, but they should be given consideration in the event conservative treatment remains inadequate and all other sources of low back pain have been investigated.

References- Alexander CE, Varacallo M. Lumbosacral Facet Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Mar 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441906

- Grgić V. [Lumbosacral facet syndrome: functional and organic disorders of lumbosacral facet joints]. Lijec Vjesn. 2011 Sep-Oct;133(9-10):330-6.

- Kozera K, Ciszek B, Szaro P. Posterior Branches of Lumbar Spinal Nerves – part II: Lumbar Facet Syndrome – Pathomechanism, Symptomatology and Diagnostic Work-up. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2017 Apr 12;19(2):101-109.

- Marcia S, Masala S, Marini S, Piras E, Marras M, Mallarini G, Mathieu A, Cauli A. Osteoarthritis of the zygapophysial joints: efficacy of percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy in the treatment of lumbar facet joint syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2012 Mar-Apr;30(2):314.

- Jackson RP, Jacobs RR, Montesano PX. 1988 Volvo award in clinical sciences. Facet joint injection in low-back pain. A prospective statistical study. Spine. 1988 Sep. 13(9):966-71.

- Falco FJ, Manchikanti L, Datta S, Sehgal N, Geffert S, Onyewu O, Singh V, Bryce DA, Benyamin RM, Simopoulos TT, Vallejo R, Gupta S, Ward SP, Hirsch JA. An update of the systematic assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks. Pain Physician. 2012 Nov-Dec;15(6):E869-907.

- Boswell MV, Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Bakshi S, Gharibo CG, Gupta S, Jha SS, Nampiaparampil DE, Simopoulos TT, Hirsch JA. A Best-Evidence Systematic Appraisal of the Diagnostic Accuracy and Utility of Facet (Zygapophysial) Joint Injections in Chronic Spinal Pain. Pain Physician. 2015 Jul-Aug;18(4):E497-533.

- Schulte TL, Pietilä TA, Heidenreich J, Brock M, Stendel R. Injection therapy of lumbar facet syndrome: a prospective study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006 Nov. 148(11):1165-72; discussion 1172.

- Nelson AM, Nagpal G. Interventional Approaches to Low Back Pain. Clin Spine Surg. 2018 Jun;31(5):188-196.

- Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Falco FJ, Boswell MV. Management of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. World J Orthop. 2016 May 18;7(5):315-37.

- Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, et al. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Spine. 2000 May 15. 25(10):1270-7.

- Cohen SP, Williams KA, Kurihara C, et al. Multicenter, randomized, comparative cost-effectiveness study comparing 0, 1, and 2 diagnostic medial branch (facet joint nerve) block treatment paradigms before lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Anesthesiology. 2010 Aug. 113(2):395-405.

- van Wijk RM, Geurts JW, Wynne HJ, et al. Radiofrequency denervation of lumbar facet joints in the treatment of chronic low back pain: a randomized, double-blind, sham lesion-controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2005 Jul-Aug. 21(4):335-44.

- Iwatsuki K, Yoshimine T, Awazu K. Alternative denervation using laser irradiation in lumbar facet syndrome. Lasers Surg Med. 2007 Mar. 39(3):225-9.

- McCormick ZL, Marshall B, Walker J, McCarthy R, Walega DR. Long-Term Function, Pain and Medication Use Outcomes of Radiofrequency Ablation for Lumbar Facet Syndrome. Int J Anesth Anesth. 2015. 2 (2):

- Juch JNS, Maas ET, Ostelo RWJG, Groeneweg JG, Kallewaard JW, Koes BW, et al. Effect of Radiofrequency Denervation on Pain Intensity Among Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: The Mint Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA. 2017 Jul 4. 318 (1):68-81.