Lymph drainage massage

Lymph drainage massage also called manual lymphatic drainage for lymphedema caused by fluid build up after cancer treatment should begin with someone specially trained in treating lymphedema. See the Lymphology Association of North America website for a list of certified lymphedema therapists in the United States (https://www.clt-lana.org/). There are different types of manual lymphatic drainage. They include Vodder, Földi, Casley-Smith and Fluoroscopy guided manual lymphatic drainage. In this type of massage, the soft tissues of the body are lightly rubbed, tapped, and stroked. It is a very light touch, almost like a brushing. Massage may help move lymph out of the swollen area into an area with working lymph vessels. Patients can be taught to do this type of massage therapy themselves.

When done correctly, massage therapy does not cause medical problems. Lymph drainage massage should NOT be done on any of the following:

- Open wounds, bruises, or areas of broken skin.

- An infection or inflammation in the swollen area

- Tumors that can be seen on the skin surface.

- Areas with deep vein thrombosis (blood clot in a vein).

- Sensitive soft tissue where the skin was treated with radiation therapy.

- Heart problems

Your lymphoedema specialist will tell you whether you can or can’t. Always check with them if you aren’t sure. If you are uncertain about having manual lymphatic drainage or doing simple lymphatic drainage, talk to your doctor or lymphoedema specialist.

When lymphedema is severe and does not get better with treatment, other problems may be the cause.

Sometimes severe lymphedema does not get better with treatment or it develops several years after surgery. If there is no known reason, doctors will try to find out if the problem is something other than the original cancer or cancer treatment, such as another tumor.

Lymphangiosarcoma is a rare, fast-growing cancer of the lymph vessels. It is a problem that occurs in some breast cancer patients and appears an average of 10 years after a mastectomy. Lymphangiosarcoma begins as purple lesions on the skin, which may be flat or raised. A CT scan or MRI is used to check for lymphangiosarcoma. Lymphangiosarcoma usually cannot be cured.

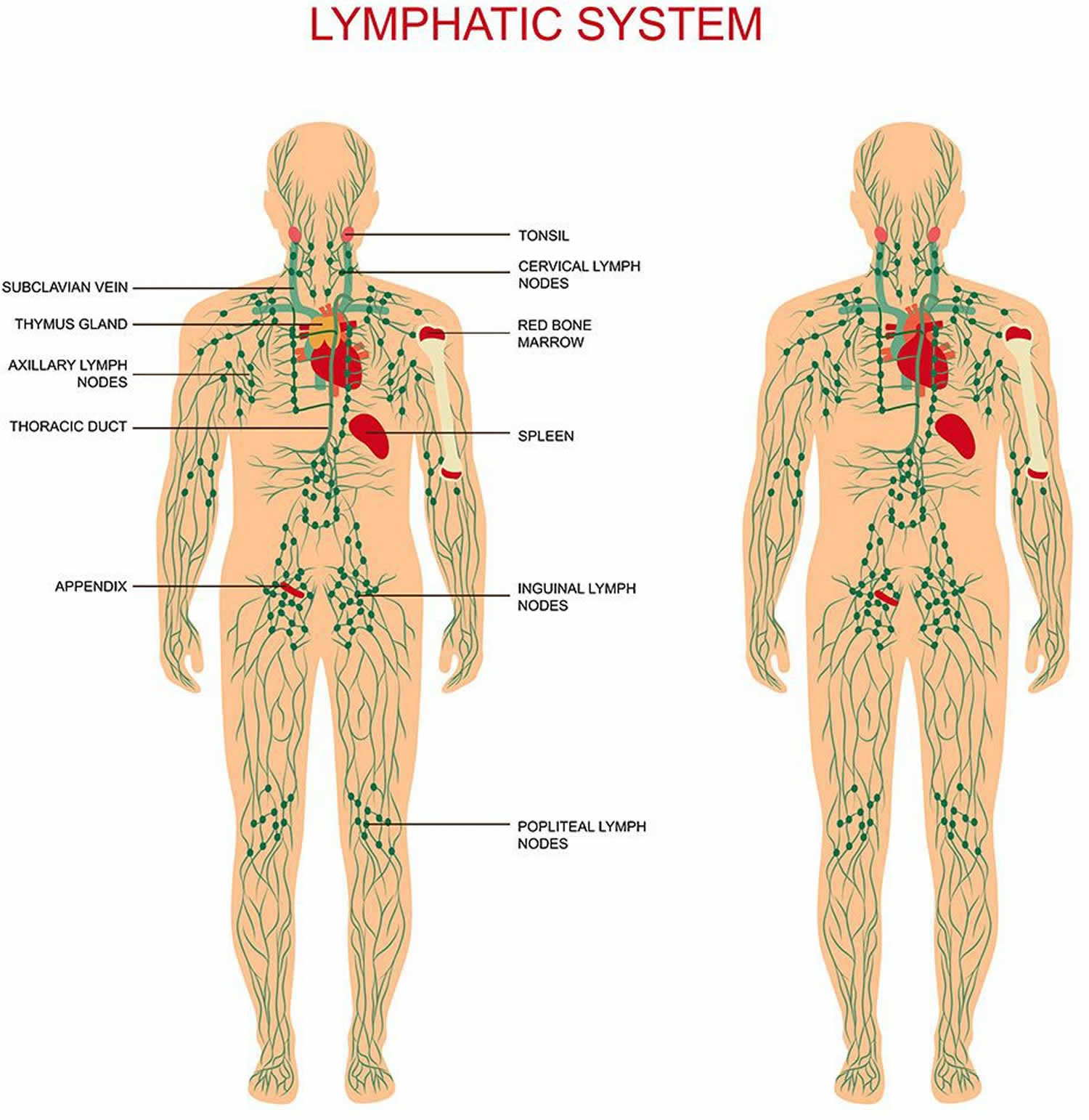

Figure 1. Lymphatic system

Simple lymphatic drainage

Simple lymphatic drainage means that you learn how to do an easier version of manual lymphatic drainage yourself. It is sometimes called self massage.

A specialist needs to teach you how to do this. Your lymphedema specialist might teach you to do simple lymphatic drainage in only the areas where you don’t have lymphedema. This frees up space for the lymph fluid to drain into from the swollen area.

You don’t do simple lymphatic drainage in the area where you have swelling. The skin movements in the swollen area are more difficult to do. Your therapist will show you how to move the skin in the surrounding areas. Ask them questions if anything is not clear.

You do simple lymphatic drainage twice a day, for about 20 minutes each time. Only apply light pressure, as your lymphedema specialist taught you.

How lymph drainage massage works

The aim of manual lymphatic drainage is to move fluid from the swollen area into a place where the lymphatic system is working normally.

To do this, the specialist first uses specialized skin movements to clear the area that they want the fluid to drain into.

It might seem strange to have skin movements on your chest and neck if you have lymphedema in your arm. But it means that the fluid has somewhere to drain to when the therapist treats your arm.

How you have manual lymphatic drainage

You usually lie down to have manual lymphatic drainage. But if you have lymphedema in your head and neck, you sit up.

When you have manual lymphatic drainage, you feel a gentle pressure. The skin movements are very light so that the small lymph vessels are not flattened. Flattened lymph vessels would prevent the lymph fluid from draining. The movements are slow and rhythmic so that the lymph vessels open up.

You might have manual lymphatic drainage daily from Monday to Friday. Or you might have it 3 times a week, for about 3 weeks.

The number of treatments you have depends on the type of manual lymphatic drainage and what you need. Your specialist will also take into account the amount of swelling you have.

After manual lymphatic drainage

The specialist might bandage the area. They use a specialized bandaging technique called multi-layered lymphedema bandaging. If it is not possible or necessary to use bandages, you will need to wear a compression garment.

Your lymphedema specialist will regularly check how well your treatment is working. They’ll look at whether the tissues are softening and how much the swelling is going down.

Once the swelling is under control, you might need another compression garment to wear.

Remember that you are the person who will notice changes in the swelling first. You need to talk to your specialist about how your treatment is working. Managing lymphedema is very much about you and the specialist working together.

Lymph massage side effects

Most people don’t have any side effects from having a massage. But you might feel a bit light headed, sleepy, tired or thirsty afterwards.

Despite the safety profile, the following special precautions should be considered when massage therapy is delivered to individuals with cancer:

- Avoid directly massaging any open wounds, hematomas, or areas with skin breakdown.

- Avoid directly massaging tumors that are apparent on the skin surface.

- Avoid massaging areas with acute deep venous thrombosis.

- Avoid directly massaging radiated soft tissue when the skin is sensitive 1.

Refractory lymphedema and complications

If lymphedema is massive and refractory to treatment, or has an onset several years after the primary surgery without obvious trauma, a search for other etiologies should be undertaken. Of particular importance is exclusion of the recurrence of tumor or the development of lymphangiosarcoma, which should be excluded with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The complication of lymphangiosarcoma is classically seen in the postmastectomy lymphedematous arm (Stewart-Treves syndrome). The mean time between mastectomy and lymphangiosarcoma is 10.2 years, with a median survival of 1.3 years. Clinically, the lesions of lymphangiosarcoma may initially appear as blue-red or purple with a macular or papular shape in the skin. Multiple lesions are common; subcutaneous nodules may appear and should be carefully evaluated in the patient who has chronic lymphedema 2.

What is lymphedema

Lymphedema is the abnormal buildup of protein-rich lymphatic fluid in soft tissue due to a blockage in the lymphatic system. This lymph fluid may contain plasma proteins, extravascular blood cells, excess water, and parenchymal products 3. Lymphedema is one of the most poorly understood, relatively underestimated, and least researched complications of cancer or its treatment. The lymphatic system helps fight infection and other diseases by carrying lymph throughout the body. Lymph is a colorless fluid containing white blood cells.

Lymph travels through your body using a network of thin tubes called vessels. Small glands called lymph nodes filter bacteria and other harmful substances out of this fluid. But when the lymph nodes are removed or damaged, lymphatic fluid collects in the surrounding tissues and makes them swell.

Lymphedema may develop immediately after surgery or radiation therapy. Or, it may occur months or even years after cancer treatment has ended. Most often, lymphedema affects the arms and legs. But it can also happen in the neck, face, mouth, abdomen, groin, or other parts of the body.

Lymphedema can occur in people with many types of cancers, including:

- Bladder cancer

- Breast cancer

- Head and neck cancer

- Melanoma

- Ovarian cancer

- Penile cancer

- Prostate cancer

Cancer and its treatment are risk factors for lymphedema.

Lymphedema can occur after any cancer or treatment that affects the flow of lymph through the lymph nodes, such as removal of lymph nodes. It may develop within days or many years after treatment. Most lymphedema develops within three years of surgery. Risk factors for lymphedema include the following:

- Removal and/or radiation of lymph nodes in the underarm, groin, pelvis, or neck. The risk of lymphedema increases with the number of lymph nodes affected. There is less risk with the removal of only the sentinel lymph node (the first lymph node in a group of lymph nodes to receive lymphatic drainage from the primary tumor).

- Being overweight or obese.

- Slow healing of the skin after surgery.

- A tumor that affects or blocks the left lymph duct or lymph nodes or vessels in the neck, chest, underarm, pelvis, or abdomen.

- Scar tissue in the lymph ducts under the collarbones, caused by surgery or radiation therapy.

Lymphedema often occurs in breast cancer patients who had all or part of their breast removed and axillary (underarm) lymph nodes removed. Lymphedema in the legs may occur after surgery for uterine cancer, prostate cancer, lymphoma, or melanoma. It may also occur with vulvar cancer or ovarian cancer. Lymphedema occurs frequently in patients with cancers of the head and neck due to high-dose radiation therapy and combined surgery.

Lymphedema may be either primary or secondary:

- Primary lymphedema is caused by the abnormal development of the lymph system. Symptoms may occur at birth or later in life.

- Secondary lymphedema is caused by damage to the lymph system. The lymph system may be damaged or blocked by infection, injury, cancer, removal of lymph nodes, radiation to the affected area, or scar tissue from radiation therapy or surgery.

Possible signs of lymphedema include swelling of the arms or legs.

Other conditions may cause the same symptoms. A doctor should be consulted if any of the following problems occur:

- Swelling of an arm or leg, which may include fingers and toes.

- A full or heavy feeling in an arm or leg.

- A tight feeling in the skin.

- Trouble moving a joint in the arm or leg.

- Thickening of the skin, with or without skin changes such as blisters or warts.

- A feeling of tightness when wearing clothing, shoes, bracelets, watches, or rings.

- Itching of the legs or toes.

- A burning feeling in the legs.

- Trouble sleeping.

- Loss of hair.

Daily activities and the ability to work or enjoy hobbies may be affected by lymphedema.

These symptoms may occur very slowly over time or more quickly if there is an infection or injury to the arm or leg.

Tests that examine the lymph system are used to diagnose lymphedema.

It is important to make sure there are no other causes of swelling, such as infection or blood clots. The following tests and procedures may be used to diagnose lymphedema:

- Physical exam and history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- Lymphoscintigraphy: A method used to check the lymph system for disease. A very small amount of a radioactive substance that flows through the lymph ducts and can be taken up by lymph nodes is injected into the body. A scanner or probe is used to follow the movement of this substance. Lymphoscintigraphy is used to find the sentinel lymph node (the first node to receive lymph from a tumor) or to diagnose certain diseases or conditions, such as lymphedema.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

The swollen arm or leg is usually measured and compared to the other arm or leg. Measurements are taken over time to see how well treatment is working.

A grading system is also used to diagnose and describe lymphedema. Grades 1, 2, 3, and 4 are based on size of the affected limb and how severe the signs and symptoms are.

Stages may be used to describe lymphedema.

- Stage 1: The limb (arm or leg) is swollen and feels heavy. Pressing on the swollen area leaves a pit (dent). This stage of lymphedema may go away without treatment.

- Stage 2: The limb is swollen and feels spongy. A condition called tissue fibrosis may develop and cause the limb to feel hard. Pressing on the swollen area does not leave a pit.

- Stage 3: This is the most advanced stage. The swollen limb may be very large. Stage III lymphedema rarely occurs in breast cancer patients. Stage III is also called lymphostatic elephantiasis.

Managing lymphedema

Patients can take steps to prevent lymphedema or keep it from getting worse.

Taking preventive steps may keep lymphedema from developing. Health care providers can teach patients how to prevent and take care of lymphedema at home. If lymphedema has developed, these steps may keep it from getting worse. Preventive steps include the following:

- Tell your health care provider right away if you notice symptoms of lymphedema. The chance of improving the condition is better if treatment begins early. Untreated lymphedema can lead to problems that cannot be reversed.

- Keep skin and nails clean and cared for, to prevent infection. Bacteria can enter the body through a cut, scratch, insect bite, or other skin injury. Fluid that is trapped in body tissues by lymphedema makes it easy for bacteria to grow and cause infection. Look for signs of infection, such as redness, pain, swelling, heat, fever, or red streaks below the surface of the skin. Call your doctor right away if any of these signs appear. Careful skin and nail care helps prevent infection:

- Use cream or lotion to keep the skin moist.

- Treat small cuts or breaks in the skin with an antibacterial ointment.

- Avoid needle sticks of any type into the limb (arm or leg) with lymphedema. This includes shots or blood tests.

- Use a thimble for sewing.

- Avoid testing bath or cooking water using the limb with lymphedema. There may be less feeling (touch, temperature, pain) in the affected arm or leg, and skin might burn in water that is too hot.

- Wear gloves when gardening and cooking.

- Wear sunscreen and shoes when outdoors.

- Cut toenails straight across. See a podiatrist (foot doctor) as needed to prevent ingrown nails and infections.

- Keep feet clean and dry and wear cotton socks.

- Avoid blocking the flow of fluids through the body. It is important to keep body fluids moving, especially through an affected limb or in areas where lymphedema may develop.

- Do not cross legs while sitting.

- Change sitting position at least every 30 minutes.

- Wear only loose jewelry and clothes without tight bands or elastic.

- Do not carry handbags on the arm with lymphedema.

- Do not use a blood pressure cuff on the arm with lymphedema.

- Do not use elastic bandages or stockings with tight bands.

- Keep blood from pooling in the affected limb.

- Keep the limb with lymphedema raised higher than the heart when possible.

- Do not swing the limb quickly in circles or let the limb hang down. This makes blood and fluid collect in the lower part of the arm or leg.

- Do not apply heat to the limb.

- Wear a pressure garment if lymphedema has developed. Pressure garments are made of fabric that puts a controlled amount of pressure on different parts of the arm or leg to help move fluid and keep it from building up. Some patients may need to have these garments custom-made for a correct fit. Wearing a pressure garment during exercise may help prevent more swelling in an affected limb. It is important to use pressure garments during air travel, because lymphedema can become worse at high altitudes. Pressure garments are also called compression sleeves and lymphedema sleeves or stockings. Patients who have lymphedema should wear a well-fitting pressure garment during all exercise that uses the affected limb or body part. When it is not known for sure if a woman has lymphedema, upper-body exercise without a garment may be more helpful than no exercise at all. Patients who do not have lymphedema do not need to wear a pressure garment during exercise.

Studies have shown that carefully controlled exercise is safe for patients with lymphedema.

Exercise does not increase the chance that lymphedema will develop in patients who are at risk for lymphedema. In the past, these patients were advised to avoid exercising the affected limb. Studies have now shown that slow, carefully controlled exercise is safe and may even help keep lymphedema from developing. Studies have also shown that, in breast-cancer survivors, upper-body exercise does not increase the risk that lymphedema will develop.

Both light exercise and aerobic exercise (physical activity that causes the heart and lungs to work harder) help the lymph vessels move lymph out of the affected limb and decrease swelling.

- Talk with a certified lymphedema therapist before beginning exercise. Patients who have lymphedema or who are at risk for lymphedema should talk with a certified lymphedema therapist before beginning an exercise routine. See the Lymphology Association of North America website for a list of certified lymphedema therapists in the United States (https://www.clt-lana.org/).

Breast cancer survivors should begin with light upper-body exercise and increase it slowly.

Some studies with breast cancer survivors show that upper-body exercise is safe in women who have lymphedema or who are at risk for lymphedema. Weight-lifting that is slowly increased may keep lymphedema from getting worse. Exercise should start at a very low level, increase slowly over time, and be overseen by the lymphedema therapist. If exercise is stopped for a week or longer, it should be started again at a low level and increased slowly.

If symptoms (such as swelling or heaviness in the limb) change or increase for a week or longer, talk with the lymphedema therapist. It is likely that exercising at a low level and slowly increasing it again over time is better for the affected limb than stopping the exercise completely.

Bandages

Once the lymph fluid is moved out of a swollen limb, bandaging (wrapping) can help prevent the area from refilling with fluid. Bandages also increase the ability of the lymph vessels to move lymph along. Lymphedema that has not improved with other treatments is sometimes helped with bandaging.

Combined therapy

Combined physical therapy is a program of massage, bandaging, exercises, and skin care managed by a trained therapist. At the beginning of the program, the therapist gives many treatments over a short time to decrease most of the swelling in the limb with lymphedema. Then the patient continues the program at home to keep the swelling down. Combined therapy is also called complex decongestive therapy.

Compression device

Compression devices are pumps connected to a sleeve that wraps around the arm or leg and applies pressure on and off. The sleeve is inflated and deflated on a timed cycle. This pumping action may help move fluid through lymph vessels and veins and keep fluid from building up in the arm or leg. Compression devices may be helpful when added to combined therapy. The use of these devices should be supervised by a trained professional because too much pressure can damage lymph vessels near the surface of the skin.

Weight loss

In patients who are overweight, lymphedema related to breast cancer may improve with weight loss.

Laser therapy

Laser therapy may help decrease lymphedema swelling and skin hardness after a mastectomy. A hand-held, battery-powered device is used to aim low-level laser beams at the area with lymphedema.

Drug therapy

Lymphedema is not usually treated with drugs. Antibiotics may be used to treat and prevent infections. Other types of drugs, such as diuretics or anticoagulants (blood thinners), are usually not helpful and may make the lymphedema worse.

Surgery

Lymphedema caused by cancer is rarely treated with surgery. The primary surgical method for treating lymphedema consists of removing the subcutaneous fat and fibrous tissue with or without creation of a dermal flap within the muscle to encourage superficial-to-deep lymphatic anastomoses. These methods have not been evaluated in prospective trials, with adequate results for only 30% of patients in one retrospective review. In addition, many patients face complications such as skin necrosis, infection, and sensory abnormalities.[19] The oncology patient is usually not a candidate for these procedures. Other surgical options include the following:

- Microsurgical lymphaticovenous anastomoses, in which the lymph is drained into the venous circulation or the lymphatic collectors above the area of lymphatic obstruction.

- Liposuction.

- Superficial lymphangiectomy.

- Fasciotomy.

- Gecsedi RA: Massage therapy for patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 6 (1): 52-4, 2002 Jan-Feb.

- Tomita K, Yokogawa A, Oda Y, et al.: Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome): ultrastructural and immunohistologic characteristics. J Surg Oncol 38 (4): 275-82, 1988.

- Meneses KD, McNees MP: Upper extremity lymphedema after treatment for breast cancer: a review of the literature. Ostomy Wound Manage 53 (5): 16-29, 2007.