Lymphatic malformation

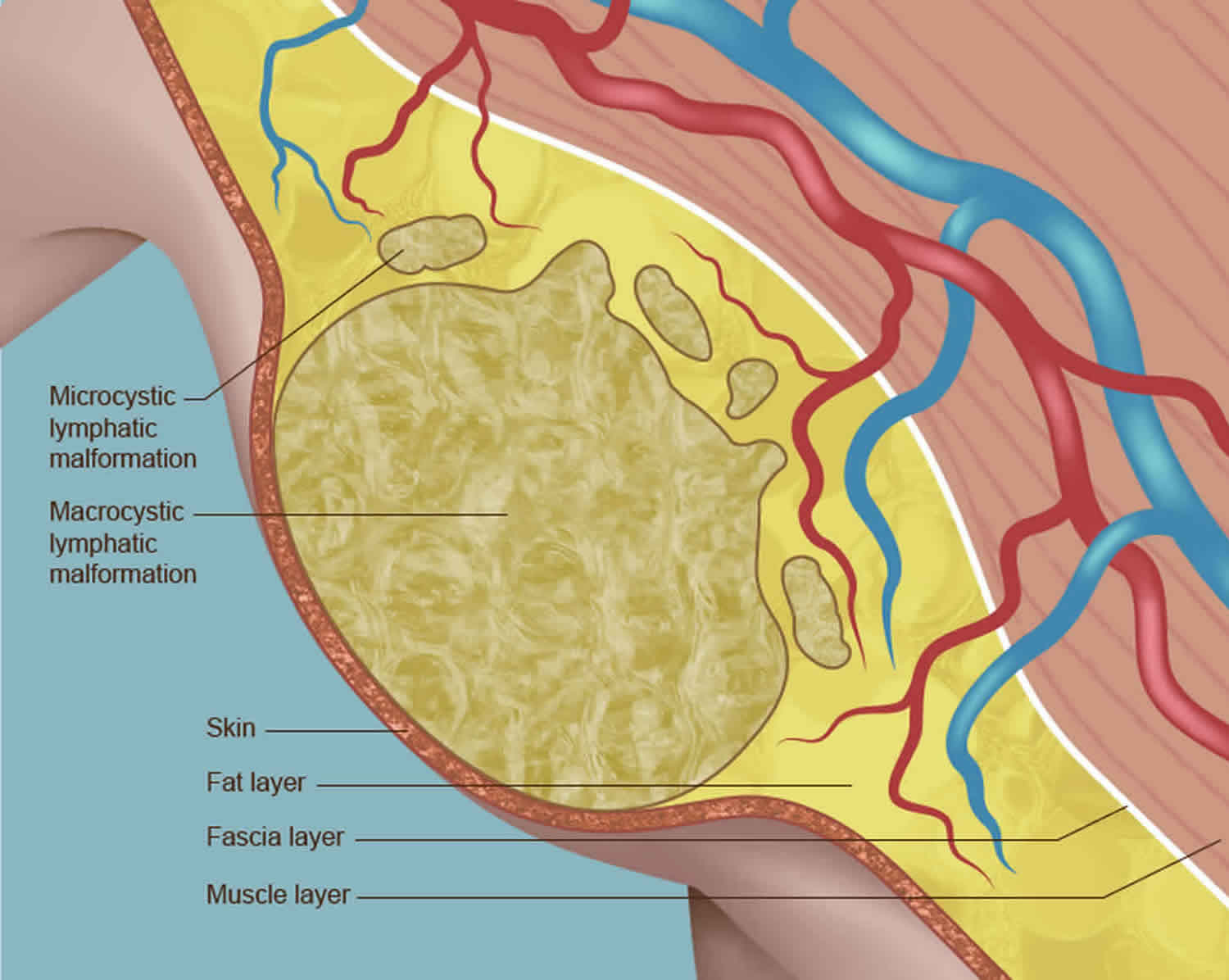

Lymphatic malformation also called macrocystic lymphatic malformation, cystic hygroma or cystic lymphangioma, is a congenital (present at birth) non-cancerous growth that contains one or more sacs, or cysts, of clear fluid (lymph) 1. Lymphatic malformation is a type of vascular nevus or birthmark due to malformed and dilated lymphatic vessels. When the cysts are small in size, they are known as microcysts. When they are large, they are called macrocysts. Although the most common locations for lymphatic malformation are the neck or head (75% of cases) with a predilection for the left side and the armpit (20% of cases), they can occur at several locations in the body including the abdomen 1, the mediastinum and groin 2. Lymphatic malformations of the neck region were historically called cystic hygromas. They often contain a combination of micro and macrocysts (Figure 2). When present in newborns, these malformations can cause significant airway problems.

Macrocystic lymphatic malformations usually develop before birth, although they may not become visible for up to the baby’s second birthday or sometimes even later.

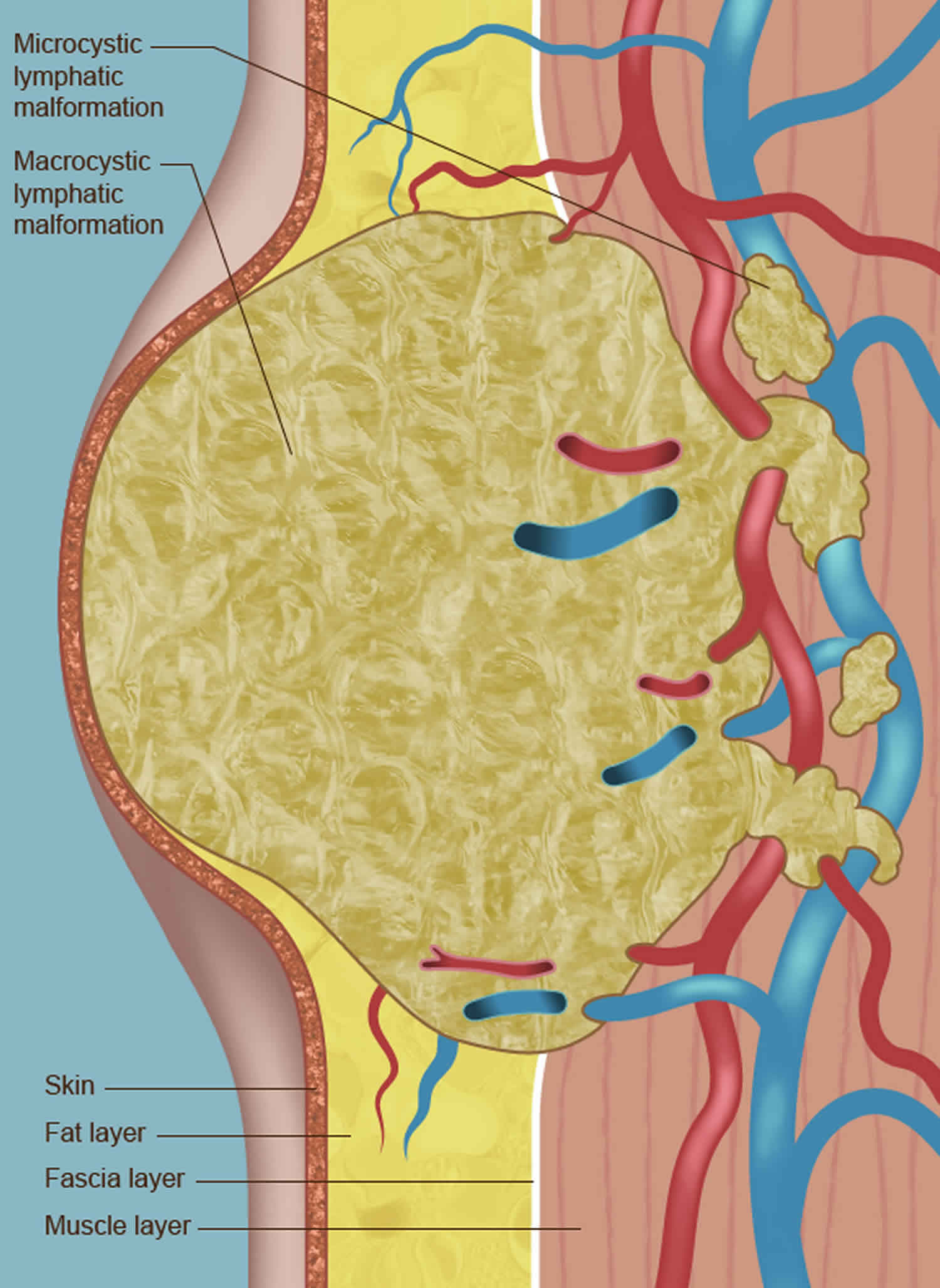

Many lymphatic malformations contain cysts of various sizes. Although lymphatic malformations are non-cancerous, they can grow quite large, causing discomfort and disfigurement (Figure 1). They can also compress and/or invade nearby organs, leading to medical complications if not treated (Figure 3).

Lymphatics are similar to veins, except they carry water (lymph) instead of blood. They are also part of the immune system. Lymphatic malformations affect only the lymph vessels, and result in water-filled cysts that range in size from microscopic to macrocysts the size of small water balloons.

Veins and lymphatics travel together, and often blood leaks into the dilated lymphatics. This can result in blood blisters and bloody crusts (angiokeratomas) on the surface of the skin which connect to deeper lymphatics below. When the skin blisters and crusts rupture, leakage of bloody lymph may give the appearance of significant bleeding. The drainage is mostly bloody water that doesn’t clot like normal blood, which can be a nuisance for parents and patients.

Lymphatic malformations can also put patients at higher risk for infections. Infections (such as cellulitis) require antibiotic therapy. If oral antibiotics are not sufficient, patients must be admitted to the hospital for intravenous antibiotics.

Lymphatic malformations of the lower extremities may be apparent at birth or may not appear until later in life as gravity begins to take effect and water accumulates in the tissues. Puberty may also play a role in the onset of edema. Various names have been given to these lymphatic malformations of the lower extremities, including lymphedema praecox, Meige’s syndrome and Milroy’s disease. A dominant hereditary component may be present due to mutations in genes that control blood vessel growth factors.

Treatment will depend on the size, extent, and symptoms of your child’s lymphatic malformation.

Several treatment approaches are available for lymphatic malformation, including the following:

- Watch-and-wait. In some cases, particularly if the cyst is small or is not threatening an airway, the best treatment approach is to simply keep the malformation under observation. Lymphatic malformations sometimes drain and shrink spontaneously.

- Percutaneous drainage. With this procedure, an incision is made into the lymphatic malformation and the fluid is drained, usually through a small tube (catheter). Percutaneous drainage is usually done in combination with sclerotherapy or surgery.

- Sclerotherapy. This treatment, which is carried out while the baby is under a general anesthesia, involves injecting a special medication into the malformation. The doctor will use ultrasound imaging to help guide the injection of the medication to the right location. The medication ablates (destroys) the cyst, collapsing its walls. The fluid is then drained away through a drainage tube. Sclerotherapy treatments may need to be repeated. Your baby will remain hospitalized until the treatments are completed and there are no signs of swelling of the airways (if the malformation is in the neck or chest area).

- Laser therapy. With this treatment, which is done under general anesthesia, the cysts are destroyed with a strong beam of light. Usually, multiple treatment sessions are needed, spread out over many months. Laser therapy is most often used to treat lymphatic malformations that involve the skin or mucous membranes (the thin layer of skin that lines the nose, mouth and other body cavities and that produces mucus to keep those cavities from drying out).

- Surgical removal. Surgery can be used to remove some lymphatic malformations, particularly those that are small and that do not surround important body parts and organs.

- Medical therapy. In some cases, medications are used to treat lymphatic malformations. One such medication is sirolimus, a drug used by organ transplant patients to keep their immune system from rejecting their new organ. One of the effects that sirolimus has on the body is to suppress the uncontrolled growth of blood vessels within the lymphatic system. By suppressing that growth, the medication shrinks existing lymphatic malformations and prevents the formation of new ones.

Figure 1. Giant macrocystic lymphatic malformation

[Source 3 ]Figure 2. Macrocystic and microcystic lymphatic malformation

Figure 3. Lymphatic malformation can expand from the skin into nearby muscles, blood vessels, and, in some cases, nerves.

Lymphatic malformation classification

There are three main types of lymphatic malformation:

- Cystic hygroma

- Cavernous lymphangioma

- Lymphangioma circumscriptum

Cystic hygroma

The cystic hygroma also called ‘cystic lymphangioma’ and ‘lymphangioma cysticum’, is a ‘macrocytic lymphatic malformation’, and is composed of large fluid-filled spaces. It appears as a skin colored, red or bluish, somewhat transparent, swelling under the skin. Cystic hygroma most often affects the neck, armpits or groin. Very large lesions may involve the chin and face, and occasionally interfere with eating or breathing. They can become infected, which may be life-threatening if the neck is involved.

Cystic hygroma is more common in some congenital disorders including Turner syndrome, hydrops fetalis, Down syndrome and fetal alcohol syndrome. So it may be advisable for babies with this type of lymphatic malformation to have chromosomal analysis performed.

An ultrasound scan is often performed to find out the extent of the abnormality. Characteristically, firm rounded spaces are detected. A cystic hygroma is distinguished from venous malformation and hemangioma by the appearance and lack of flow of the fluid.

In more complicated cases it may be necessary to perform Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or angiography to help plan treatment.

Cavernous lymphangioma

Cavernous lymphangioma can affect any site on the body, including the tongue. It presents as a skin colored, red or bluish rubbery swelling under the skin. Sometimes it has a period of fast growth in early childhood. Rarely, it may ulcerate. It is distinguished from other vascular nevi by the presence of clear fluid within the lumps and the findings on ultrasound scan.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum

Lymphangioma circumscriptum is a ‘microcytic lymphatic malformation’. It appears as a cluster of small firm blisters filled with lymph fluid, resembling frogspawn. These range in colour from clear to pink, dark red, brown or black and may become warty, especially when affecting a palm or sole. Lymphangioma circumscriptum is most commonly found on the shoulders, neck, underarm area, limbs, and in the mouth, especially the tongue. The patches may become more prominent at puberty and may ooze or bleed. Occasionally they become infected.

Lymphatic malformation causes

The cause of lymphatic malformation is not fully understood. The lymphatic system of the body is derived between 12th and 16th weeks of gestation from endothelial channels located in the neck, root of the mesentery, and the femoral and sciatic vein bifurcation 4. Sequestration of the lymphatic channels leads to the development of lymphatic malformations. Continued growth of these lesions represents both the accumulation of fluid and the proliferation of pre-existing spaces.

Lymphatic malformations are the result of problems that develop before birth in the vessels of the lymphatic system, which plays a central role in defending the body against infection and disease. The vessels drain watery fluid (lymph) from tissue and transport it to the lymph nodes, where bacteria, viruses and other harmful pathogens are destroyed. The vessels then send the cleaned-up fluid back into the bloodstream.

A lymphatic malformation occurs when the vessels do not form properly and become blocked and enlarged. Lymph then collects in them, leading to the creation of fluid-filled cysts. The cysts usually get bigger as the unborn baby grows, although sometimes they spontaneously shrink or even disappear.

When a lymphatic malformation is detected very early in pregnancy, it may be associated with a chromosomal anomaly, such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Turner syndrome or Noonan syndrome. It may also be associated with other birth defects, such as a heart defect. For these reasons, careful follow-up with ultrasound surveillance will be recommended.

Lymphatic malformation symptoms

The presenting signs and symptoms of a lymphatic malformation vary, depending on the lesion’s location. Lymphatic malformations are always present at birth, although they may be missed; they tend to become more obvious during infancy and childhood. They may vary in size from a small dot to occasionally involving a whole limb. Although lymph is a clear fluid, lymphatic malformations often appear red or blue because of the involvement of adjacent blood vessels.

Most commonly, lymphatic malformations look like bumpy lesions that are red, pink, purple, black, and/or brown in color. They are usually no more than an inch in diameter or smaller but can become quite large or can affect more than one area. They often are found on the mouth, neck, shoulders, armpits, or limbs. More rarely, lymphatic malformations reach beyond the surface of the skin and deeper into lymph glands, which can cause significant interference with the circulation of lymph throughout the body and may interfere with breathing, eating, and/or speaking.

Rarely, children with lymphatic malformations display symptoms of newly onset obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. This situation may involve children with lymphatic malformation or other space-occupying lesions of the supraglottic or paraglottic region. Suprahyoid lymphangiomas tend to cause more breathing difficulties than infrahyoid lesions.

Potentially life-threatening airway compromise that manifests as noisy breathing (stridor) and cyanosis is a possible symptom of lymphangiomas.

Feeding difficulties, as well as failure to thrive, may alert the clinician to a potential lymphangioma. This is especially true when the lesion affects structures of the upper aerodigestive tract.

Rare locations, such as the middle ear, have been reported 5.

Lymphatic malformation complications

Complications of lymphatic malformations include the following:

- Airway obstruction

- Hemorrhage

- Infection

- Deformation of surrounding bony structures or teeth (if an lymphatic malformation is left untreated)

Lymphatic malformation diagnosis

Lymphatic malformations that present early in pregnancy typically form between the 9th and 16th week of pregnancy, and are often diagnosed during a routine prenatal ultrasound exam or genetic screening exam. You will be referred to a genetic specialist, as early lymphatic malformations may be associated with chromosomal abnormalities. A detailed ultrasound will also be recommended later in pregnancy to evaluate your baby’s anatomy, since an early lymphatic malformation may also indicate the presence of another birth defect. Part of that evaluation will be done by a pediatric cardiologist, who will assess the baby’s heart anatomy.

Lymphatic malformations that present later in pregnancy may be detected during a routine ultrasound, or your doctor may note that your abdomen appears larger than expected for your weeks in pregnancy and order an ultrasound. If your doctor suspects the presence of one of these malformations by ultrasound imaging, he or she may recommend further imaging tests, such as fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to evaluate the extent of the malformation and any possible impact it may be having on the development of the baby’s internal organs.

After you baby is born, a full physical exam and blood tests will be conducted. Imaging like traditional X-rays; angiography, which uses an injectable dye and X-rays; computed tomography (CT) scan, which produces a three dimensional view of the scanned area; and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which uses powerful magnets and radio waves to create detailed organ and tissue mapping.

Lymphatic malformation treatment

Lymphatic malformation treatment goal will be to have your baby’s birth occur as near to your due date as possible, but infants with a large lymphatic malformation must sometimes be delivered early and by cesarean section. Because lymphatic cysts may drain and shrink spontaneously, conservative observation is a reasonable treatment option when the airway is not involved, but it is not predictable. If the lymphatic malformation is pressing against your baby’s airway, a mechanical breathing machine (ventilator) may be used to help your baby breathe. If the growth is interfering with your baby’s ability to nurse or take a bottle, your baby may also be placed on special intravenous (IV) lines for the delivery of needed nutrients and medications.

Your baby will undergo further tests after birth to help doctors make a definitive diagnosis of the extent of the lymphatic malformation and determine possible treatments. These tests will include advanced imaging techniques, such as ultrasound, MRI and a special type of x-ray known as computed tomography (CT) scanning. CT images are more detailed than standard x-rays.

Once a thorough assessment of your baby’s condition has been made, your doctor will explain the findings to you and what they mean in terms of treatment. The treatment option(s) that will be best for your baby will depend on the size and location of the lymphatic malformation, as well as other factors, including your baby’s overall health, your baby’s ability to tolerate specific medications and procedures, and your overall preferences.

Sclerotherapy is the most common treatment for large macrocystic lymphatic malformation. Sclerotherapy may require several consecutive days of injection and catheter drainage combined with intubation to protect the airway. Patients undergoing sclerotherapy for large macrocysts will be monitored in an intensive care unit setting.

Lymphatic malformations comprised of mostly microcysts don’t respond as well to sclerotherapy, and sometimes surgical debulking is useful to decrease the soft tissue fullness. However, lymphatic malformations are associated with repeated bouts of inflammation, which can make dissection difficult. Injury to facial nerves during surgical resection is also a significant concern. Careful nerve monitoring and the use of nerve stimulators to identify important nerves during the operation are used to decrease this risk.

The carbon dioxide laser and a KTP laser are sometimes useful for superficial skin lymphatic cysts and angiokeratomas. The treatments are not curative, but they may result in significant improvement, especially for problematic areas that tend to bleed.

For lymphatic malformations of the lower extremities, surgical treatment tends to be suboptimal, and a lifetime of compression stockings and compression pumps may provide the best long-term results.

Lymph node transfers, which are effective for acquired lymphedema after lymph node dissections for cancer surgery, are not expected to be useful in hereditary lymphedema and congenital lymphatic malformations because of the lack of normal lymphatics.

Oral sirolimus (which inhibits angiogenesis) and sildenafil (which causes dilation of blood vessels) are undergoing investigation as a potential medical treatments for severe lymphatic malformations but may have significant adverse effects 6.

Lymphatic malformation life expectancy

In the absence of genetic anomalies, the prognosis for babies born with lymphatic malformations is excellent. They have normal, active, happy lives. Outcomes are more variable for babies born with genetic anomalies. Their prognosis depends on the extent of the anomaly.

In some case series, the reported mortality has been as high as 2-6%, usually secondary to pneumonia, bronchiectasis, and airway compromise. Obviously, this figure is pertinent in the larger-sized lymphatic malformations.

As would be expected, morbidity depends on the anatomic location of the lymphatic malformation. In general, morbidity is related to cosmetic disfigurement and impingement on other critical structures, such as nerves, vessels, lymphatics, and the airway.

Unlike hemangiomas, lymphatic malformations do not commonly resolve spontaneously. Recurrence is rare when all gross disease is removed. If residual tissue is left behind, the expected recurrence rate is approximately 15%.

In antenatal cystic hygroma, diagnosis after 30 weeks’ gestation is considered a positive prognosticator. A study by Lejeunesse et al 7 involving 69 fetuses with lymphatic malformations diagnosed in the first trimester suggested that the following were predictors of a poor outcome:

- Nuchal thickness greater than 6.0-6.5 mm

- Presence of hydrops fetalis, abnormalities on ultrasound, or both

- Fetal karyotypic abnormalities, evolution of lymphatic malformation on ultrasound, or both

A study by Sanhal et al 8 found that fetuses with septated lymphatic malformations had with poor perinatal outcomes.

Because of the potential health issues associated with lymphatic malformations and because treatments must often be repeated, your baby is likely to require long-term follow-up care.

References- Lal A, Gupta P, Singhal M, et al. Abdominal lymphatic malformation: Spectrum of imaging findings. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2016;26(4):423–428. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.195777 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5201068

- Ueno S, Fujino A, Morikawa Y, Iwanaka T, Kinoshita Y, Ozeki M, et al. Treatment of mediastinal lymphatic malformation in children: an analysis of a nationwide survey in Japan. Surg Today. 2018 Jul. 48 (7):716-725.

- Uresti MA, Zertuche JT, García AL, et al. Giant Macrocystic Lymphatic Malformation in a Neonate. J Neonatal Surg. 2017;6(1):21. Published 2017 Jan 1. doi:10.21699/jns.v6i1.383 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5224755

- Retroperitoneal lymphangioma: an unusual location and presentation. Wilson SR, Bohrer S, Losada R, Price AP. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Mar; 41(3):603-5.

- Tanna N, Sidell D, Schwartz AM, Schessel DA. Cystic lymphatic malformation of the middle ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008 Nov. 117 (11):824-6.

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, Feinstein JA, Lane AT, Bruckner AL. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jan 26;366(4):384-6.

- Lajeunesse C, Stadler A, Trombert B, Varlet MN, Patural H, Prieur F, et al. [First-trimester cystic hygroma: prenatal diagnosis and fetal outcome]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2014 Jun. 43 (6):455-62.

- Sanhal CY, Mendilcioglu I, Ozekinci M, Yakut S, Merdun Z, Simsek M, et al. Prenatal management, pregnancy and pediatric outcomes in fetuses with septated cystic hygroma. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2014 Sep. 47 (9):799-803.