What is microhematuria

Microhematuria also called asymptomatic microscopic hematuria, is defined as the presence of three or more red blood cells per high-power field visible in a properly collected urine specimen without evidence of infection 1. Other abnormalities (e.g., pyuria, bacteriuria, contaminants) or obvious benign causes must be absent. A positive dipstick result alone may not be used to diagnose asymptomatic microhematuria, although microscopic examination may be performed to confirm or refute the diagnosis. History, physical examination, and laboratory tests can rule out benign causes such as infection, menstruation, vigorous exercise, medical renal disease, viral illness, trauma, or recent urologic procedures.

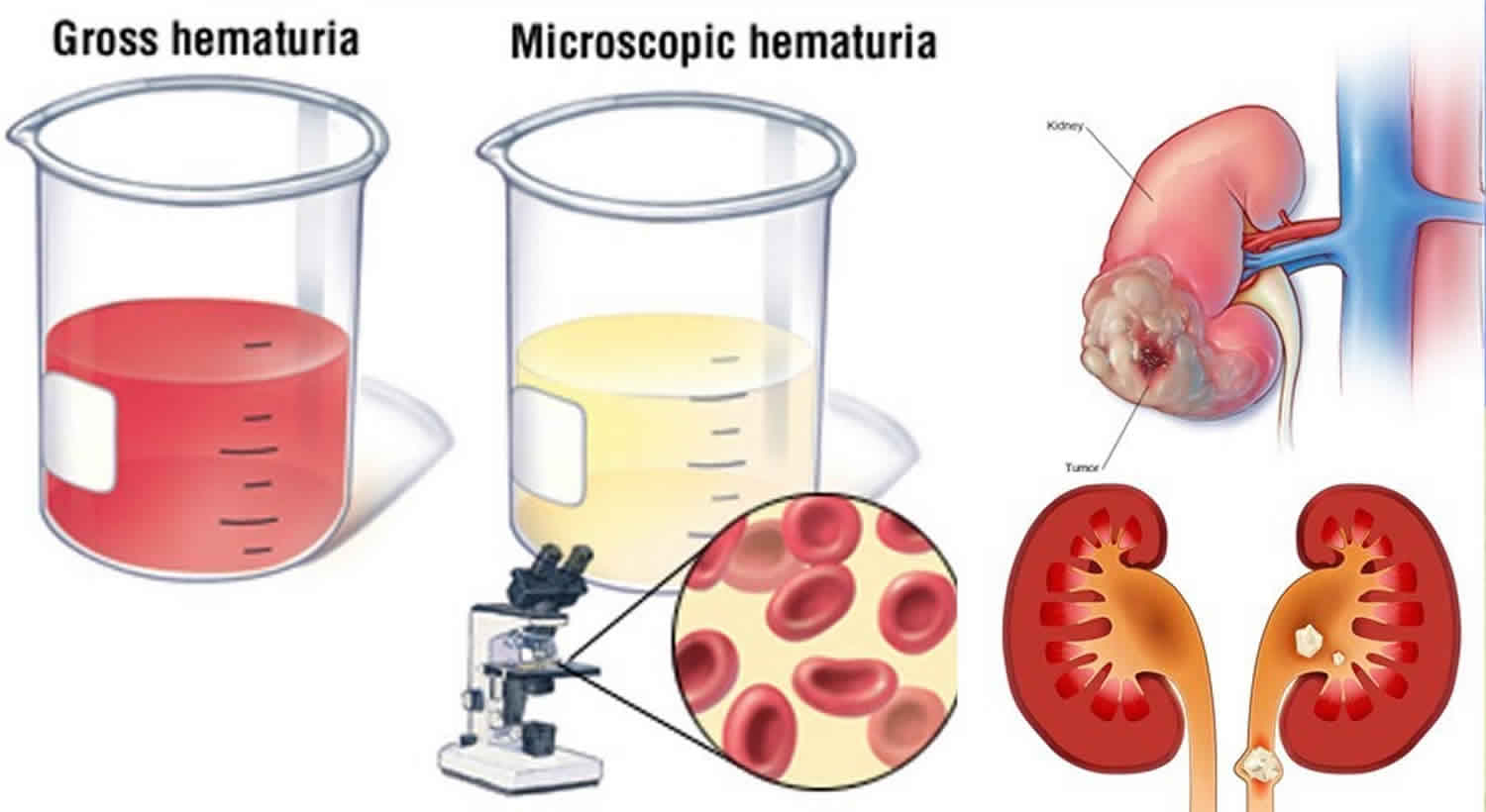

“Microscopic” means something is so small that it can only be seen through a special tool called a microscope. “Hematuria” means blood in the urine. So, if you have microscopic hematuria, you have red blood cells in your urine. These blood cells are so small, though, that you can’t see the blood when you urinate.

Microhematuria (microscopic hematuria) is a common incidental finding during routine health screenings by primary care physicians, with a prevalence of about 2%–31% 2. Many causes of microhematuria do not require a full diagnostic workup, including vigorous exercise, infection or viral illness, menstruation, exposure to trauma, or recent urologic procedures (e.g., catheterization). If a potential benign cause is identified, the insult should be removed or treated appropriately, and the urine retested after at least 48 hours. Persistent hematuria warrants a full workup 3.

The most common causes of microscopic hematuria are urinary tract infection, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and urinary calculi. However, up to 5% of patients with microscopic hematuria are found to have a urinary tract malignancy 1. The workflow of persistent microhematuria includes, among others, a physical examination, a complete medical history, laboratory evaluation (complete blood count and coagulation studies), urinalysis with culture, urine cytology, a variety of imaging modalities (renal and bladder ultrasonography, CT urogram or magnetic resonance urogram, and retrograde pyelogram), and urethrocystoscopy. If imaging studies reveal contrast-filling defects in the upper urinary tract, it is essential to differentiate malignant from benign causes by flexible ureterorenoscopy (fURS) with biopsies. Nonmalignant causes of contrast-filling defects are radiolucent stones, debris, endometriosis, nephrogenic adenoma, mycetomas, malakoplakia, inflammatory pseudotumors, blood clots, and renal papillary hyperplasia.

Microhematuria causes

The most common causes of microscopic hematuria are urinary tract infection, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and urinary calculi 4. However, up to 5% of patients with asymptomatic microhematuria are found to have a urinary tract malignancy 5. The risk of urologic malignancy is increased in men, persons older than 35 years, and persons with a history of smoking.

Hundreds of diseases have been shown to cause hematuria. In the small percentage of patients for whom an etiology is identified, causes may include urinary tract infection, benign prostatic hyperplasia, medical renal disease, urinary calculi, urethral stricture disease, and urologic malignancy 6.

In many patients with microhematuria, a specific cause or pathology is not found 7.

Some of the most common causes of blood in the urine include:

- Kidney infections.

- Enlarged prostate.

- Urinary tract (bladder) infection.

- Swelling in the filtering system of the kidneys (this is called “glomerulonephritis”).

- A stone in your bladder or in a kidney.

- A disease that runs in families, such as cystic kidney disease.

- Some medicines.

- A blood disease, like sickle cell anemia.

- A tumor in your urinary tract (this may or may not be cancer).

- Exercise (when this is the cause, hematuria will usually go away in 24 hours).

Table 1 lists the most common etiologies after initial evaluation of microscopic hematuria 7. The risk of urologic malignancy increases significantly in men, persons older than 35 years, and persons with a history of smoking 8. Table 2 lists other factors that have been shown to increase the risk of urologic malignancy in patients with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria 6.

Table 1. Common causes of microhematuria

| Diagnosis | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

Unknown | 43 to 68 |

Urinary tract infection | 4 to 22 |

Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 10 to 13 |

Urinary calculi | 4 to 5 |

Bladder cancer | 2 to 4 |

Renal cystic disease | 2 to 3 |

Renal disease | 2 to 3 |

Kidney cancer | < 1 |

Prostate cancer | < 1 |

Urethral stricture disease | < 1 |

Table 2. Common risk factors for urinary tract malignancy in patients with microhematuria

- Age older than 35 years

- Analgesic abuse

- Exposure to chemicals or dyes (benzenes or aromatic amines)

- Male sex

- Past or current smoking

- History of any of the following:

- Chronic indwelling foreign body

- Chronic urinary tract infection

- Exposure to known carcinogenic agents or alkylating chemotherapeutic agents

- Gross hematuria

- Irritative voiding symptoms

- Pelvic irradiation

- Urologic disorder or disease

Microhematuria prevention

You may not be able to prevent microscopic hematuria, depending on what causes it. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend drinking plenty of fluids, especially when you are exercising.

Microhematuria guidelines

The American Urological Association has released a guideline to direct physicians and patients during the diagnosis, evaluation, and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria in adults 6. Figure 1 is an algorithm for the diagnosis, evaluation, and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria.

Urologic evaluation of asymptomatic microhematuria is recommended after benign causes have been ruled out. Initially, renal function should be assessed using estimated glomerular filtration rate, serum creatinine level, and blood urea nitrogen level because intrinsic renal disease may indicate renal-related risks in patients. Concurrent nephrologic workup is recommended if dysmorphic red blood cells, proteinuria, cellular casts, renal insufficiency, or any other clinical indicator of renal parenchymal disease is present. Patients who are taking anticoagulants should undergo urologic and nephrologic evaluation, regardless of the type or level of anticoagulation therapy.

All patients 35 years or older who have asymptomatic microhematuria should undergo cystoscopy. For patients younger than 35 years, cystoscopy should be performed at the physician’s discretion. Regardless of age, patients with risk factors for urinary tract malignancies (e.g., irritative voiding symptoms, current or past tobacco use, chemical exposures) should undergo cystoscopy.

Imaging should be included in the initial evaluation of asymptomatic microhematuria. Multiphasic computed tomography (CT) urography (with or without intravenous contrast media) is the preferred method because it has the highest sensitivity and specificity for imaging the upper tracts. Sufficient phases are needed to rule out a mass in the renal parenchyma, as well as an excretory phase to evaluate the urothelium of the upper tracts. Magnetic resonance urography (with or without intravenous contrast media) may be used if patients have contraindications to multiphasic CT (e.g., renal insufficiency, contrast media allergy, pregnancy). Additionally, if patients have a contraindication and collecting system detail is necessary, combining magnetic resonance imaging with retrograde pyelograms allows for evaluation of the entire upper tracts. If magnetic resonance imaging cannot be performed because of metal in the body, combining noncontrast CT or renal ultrasonography with retrograde pyelograms also allows for evaluation of the entire upper tracts.

Urine cytology and urine markers (nuclear matrix protein 22, bladder tumor antigen stat, and Urovysion fluorescence in situ hybridization) are not recommended for the routine evaluation of asymptomatic microhematuria. Cytology may be useful, however, in patients with persistent microhematuria after a negative workup or with risk factors for carcinoma in situ (e.g., irritative voiding symptoms, current or past tobacco use, chemical exposures). Blue light cystoscopy is not recommended for evaluating asymptomatic microhematuria.

After a negative urologic workup, yearly urinalysis is recommended in patients with persistent asymptomatic microhematuria, although they may be discontinued after two consecutive negative results. A repeat evaluation within three to five years should be considered in patients with persistent or recurrent asymptomatic microhematuria after an initial negative urologic workup.

Figure 1. Microhematuria guidelines

Footnote: Algorithm for the diagnosis, evaluation, and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria in adults.

[Source 6 ]Microhematuria symptoms

Most of the time, you will not have any symptoms of microscopic hematuria. Sometimes you may feel a burning sensation when you urinate. Or you may feel the urge to urinate more often than usual.

Microhematuria diagnosis

Your doctor will usually start by asking you for a urine sample. He or she will test your urine (urinalysis) for the presence of red blood cells. Your doctor will also check for other things that might explain what is wrong. For example, white blood cells in your urine usually mean that you have an infection. If you do have blood in your urine, your doctor will ask you some questions to find out what caused it.

If the cause isn’t clear, you may have to have more tests. You might have an ultrasound or an intravenous pyelogram (this is like an X-ray). A special tool, such as a cytoscope or an endoscope, may be used to look inside your bladder. These tests are usually done by a urologist.

How do I give a urine sample?

A nurse will give you an antiseptic wipe (to clean yourself) and a sterile urine collection cup. In the bathroom, wash your hands with soap and warm water first.

- For women: Use the antiseptic wipe to clean your vagina. Do this by wiping yourself from front to back 3 times before you urinate. Fold the wipe each time you use it, so that you are wiping with a clean part each time.

- For men: Use the antiseptic wipe to clean the head of your penis. If you’re not circumcised, pull the foreskin back behind the head of the penis before you use the wipe. Move the wipe around the head of your penis before you urinate.

- Start urinating in the toilet. About halfway through the urination, start catching the urine in the cup.

- Wash your hands with soap and warm water.

- Give the sample to the nurse. Someone will look at your urine under a microscope to see if it has blood in it.

According to the American Urological Association, the presence of three or more red blood cells on a single, properly collected, noncontaminated urinalysis without evidence of infection is considered clinically significant microscopic hematuria 6. If the specimen shows large amounts of squamous epithelial cells (more than five per high-power field) or if the patient is unable to provide an uncontaminated specimen secondary to anatomic constraints (e.g., obesity, phimosis), catheterization should be used to obtain a specimen 6.

The use of a simple urine dipstick test for identifying microscopic hematuria has a sensitivity greater than 90%; however, there is a considerable false-positive rate (up to 35%) 9, necessitating follow-up microscopic analysis for all positive results. Referral to a subspecialist should not be initiated until the hematuria is confirmed.18 False-positive results on a urine dipstick test can occur in the presence of hemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria, semen, highly alkaline urine (pH greater than 9), and concentrated urine 10. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) has been shown to cause false-negative results on dipstick testing because of its reducing properties; therefore, patients taking vitamin C supplements and undergoing urinary evaluation may benefit from up-front microscopic examination 11.

POSITIVE DIPSTICK TEST AND NEGATIVE MICROSCOPIC RESULTS

Patients who screen positive for hematuria with a urine dipstick test but have a negative follow-up microscopic examination should undergo three additional microscopic tests to rule out hematuria. If one of these repeat test results is positive on microscopic analysis, the patient is considered to have microscopic hematuria. If all three specimens are negative on microscopy, the patient does not require further evaluation for hematuria 6 and other causes of a positive dipstick test result, such as hemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria, should be considered.

HEMATURIA WITH URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

If a patient has microscopic hematuria in the presence of pyuria or bacteriuria, a urine culture should be obtained to rule out urinary tract infection. Culture-directed antibiotics should be administered, and a microscopic urinalysis should be repeated in six weeks to assess for resolution of the hematuria 6. If the hematuria has resolved after the infection has cleared, no further workup is needed. If hematuria persists, diagnostic evaluation should commence 6.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF MEDICAL RENAL DISEASE

The presence of microscopic hematuria and dysmorphic red blood cells, cellular casts, proteinuria, elevated creatinine level, or hypertension should raise suspicion for medical renal etiologies, such as immunoglobulin A nephropathy, Alport syndrome, benign familial hematuria, or other nephropathy. If any of these are suspected, concurrent nephrologic workup is warranted 12. However, these findings do not exclude the potential for urologic processes, and evaluation for such causes should be conducted 6.

Initial Evaluation

All patients with confirmed asymptomatic microscopic hematuria should provide a patient history and have a physical examination that includes blood pressure measurement and a laboratory assessment 10. Asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in patients who are taking anticoagulants requires urologic and nephrologic evaluation, regardless of the type or level of anticoagulant therapy 6. A pelvic examination should be performed in women to identify urethral masses, diverticula, atrophic vaginitis, or a uterine source of bleeding. A rectal examination is necessary in men to evaluate the size and presence of nodularity in the prostate. A serum creatinine level should be obtained to screen for medical renal disease and to evaluate renal function before performing a contrast-enhanced radiology test.

Imaging of the upper urinary tract

Upper urinary tract imaging can occur before consultation with a urologist if microscopic hematuria without a known cause has been confirmed 6. Historically, the preferred choice for upper tract imaging was intravenous pyelography. However, this study has been largely replaced by multiphasic computed tomography (CT) urography, which combines a noncontrast phase to diagnose hydronephrosis and urinary calculi, a nephrogenic phase to evaluate the renal parenchyma for pyelonephritis or neoplastic lesions and an excretory phase to detect urothelial disease, appearing as filling defects 13. CT urography is the imaging procedure of choice in the evaluation of microscopic hematuria because of its high sensitivity (91% to 100%) and specificity (94% to 97%), and its ability to provide excellent diagnostic information in a single imaging session 6.

A major concern with the use of CT urography is radiation exposure. The average effective dose of radiation with CT urography (7.7 mSv) is more than double that of intravenous pyelography (3 mSv) 14. In an attempt to decrease radiation exposure, new lower-dose protocols and synchronous acquisition of nephrogenic and excretory phase images have been employed 15. The use of CT urography is precluded in radiation-sensitive populations (e.g., pregnant women) and in persons with renal insufficiency or contrast media allergies. In these patients, alternative imaging options include renal ultrasonography, magnetic resonance urography, and retrograde pyelography 13.

Renal ultrasonography is less sensitive (50% sensitive and 95% specific) in detecting urothelial lesions, small renal masses, and urinary calculi 16. Furthermore, renal ultrasonography does not reliably produce diagnostic certainty, and may lead to indeterminate findings that result in additional imaging and costs 6. Magnetic resonance urography is used less often because of its relatively high cost, lack of availability, and the absence of standardized protocols. Additionally, it is poor at detecting stone disease, which is a common etiology of microscopic hematuria 17. However, advances in technology may increase the use of magnetic resonance urography in some populations because the sensitivity of detecting renal lesions is greater than 90% 18. Patients with moderate to severe renal insufficiency are now advised to avoid gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging because of the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis 19. To safely evaluate the entire upper tract in this population, retrograde pyelography, which detects urothelial filling defects, can be used in combination with noncontrast CT or ultrasonography. Although the test is invasive, when it is combined with renal ultrasonography, the sensitivity and specificity are 97% and 93%, respectively 20.

The appropriate upper tract imaging method should be determined by clinical circumstances, patient preferences, and available resources. A more limited or alternative evaluation may be sufficient in some low-risk patients, particularly those younger than 35 years without other risk factors in whom the risk of malignancy is low 6. In pregnant women, the prevalence of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria is similar to that of nonpregnant women, and most etiologies of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in pregnancy are not life-threatening 21. Therefore, the American Urological Association recommends magnetic resonance urography or retrograde pyelography in combination with renal ultrasonography to screen for major renal lesions in pregnant women. A full workup should be completed after delivery and after persistent infection and gynecologic bleeding have been resolved 6.

Evaluation of the lower urinary tract

Cystoscopy is recommended in all patients with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria who present with risk factors for malignancy, regardless of age (Table 2) 6. Cystoscopy can identify urethral stricture disease, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and bladder masses. In patients younger than 35 years, the probability of urinary tract malignancy is low; therefore, in the absence of risk factors, cystoscopy should be performed at the discretion of the urologist.6,40,41 Voided urine cytology is less sensitive than cystoscopy in the detection of bladder cancer (48% vs. 87%) 12 and the American Urological Association guideline no longer recommends it as part of the routine evaluation of microscopic hematuria 6. Reasons for this include test interpretation subjectivity, a wide variation in what is considered abnormal, and unnecessary and costly workups resulting from diagnoses such as atypical cytology 22. However, in patients with risk factors for carcinoma in situ (e.g., irritative voiding, tobacco use, chemical exposures), cytology may still be useful 6. There are new, rapid urinary assays available for bladder cancer detection (e.g., nuclear matrix protein 22 test, bladder tumor antigen stat test, urinary bladder cancer antigen, fluorescence in situ hybridization), but these have not been shown to be superior to cystoscopy or cytology in the initial detection of urothelial malignancies and should not be obtained by primary care physicians 23.

Follow-up

If appropriate workup does not reveal nephrologic or urologic disease, then annual urinalysis should be performed for at least two years after initial referral. If these two urinalyses do not show persistent hematuria, the risk of future malignancy is less than 1% 24 and the patient may be released from care. However, if asymptomatic microscopic hematuria persists on follow-up urinalysis, a full repeat evaluation should be considered within three to five years of the initial evaluation.6 Patients’ risk factors for urologic malignancy should guide clinical decision making about reevaluation 25.

Microhematuria treatment

If the cause of the blood in your urine is evident, your doctor will probably treat you. Then your doctor will check your urine again to see if the blood is gone. If it’s not, your doctor may perform more tests or refer you to a urologist.

If you have no symptoms of microscopic hematuria, you may not know to alert your doctor. But if you do have symptoms, call your doctor right away. It is always important to find out the cause of blood in your urine.

References- Heißler O, Seklehner S, Riedl C. Renal Papillary Hyperplasia as a Cause of Persistent Asymptomatic Microhematuria. J Endourol Case Rep. 2018;4(1):152–154. Published 2018 Sep 20. doi:10.1089/cren.2018.0060 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6151332

- Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults: AUA guideline. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, Castle EP, Lang EK, Leveillee RJ, Messing EM, Miller SD, Peterson AC, Turk TM, Weitzel W, American Urological Association. J Urol. 2012 Dec; 188(6 Suppl):2473-81.

- Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults: AUA guideline. American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc., 2012:1–30.

- Assessment of Asymptomatic Microscopic Hematuria in Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Dec 1;88(11):747-754. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/1201/p747.html

- Khadra MH, Pickard RS, Charlton M, Powell PH, Neal DE. A prospective analysis of 1,930 patients with hematuria to evaluate current diagnostic practice. J Urol. 2000;163(2):524–527

- Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults: AUA guideline. American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc., 2012:1–30

- Elias K, Svatek RS, Gupta S, Ho R, Lotan Y. High-risk patients with hematuria are not evaluated according to guideline recommendations. Cancer. 2010;116(12):2954–2959

- Chou R, Dana T. Screening adults for bladder cancer: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(7):461–468

- Rao PK, Jones JS. How to evaluate ‘dipstick hematuria’: what to do before you refer. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(3):227–233

- Gerber GS, Brendler CB. Evaluation of the urologic patient: history, physical examination, and urinalysis. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders; 2011:86–87

- Brigden ML, Edgell D, McPherson M, Leadbeater A, Hoag G. High incidence of significant urinary ascorbic acid concentrations in a west coast population—implications for routine urinalysis. Clin Chem. 1992;38(3):426–431

- Cohen RA, Brown RS. Clinical practice. Microscopic hematuria. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(23):2330–2338

- O’Connor OJ, McSweeney SE, Maher MM. Imaging of hematuria. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008;46(1):113–132

- Eikefjord EN, Thorsen F, Rørvik J. Comparison of effective radiation doses in patients undergoing unenhanced MDCT and excretory urography for acute flank pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(4):934–939

- Chow LC, Kwan SW, Olcott EW, Sommer G. Split-bolus MDCT urography with synchronous nephrographic and excretory phase enhancement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(2):314–322

- El-Galley R, Abo-Kamil R, Burns JR, Phillips J, Kolettis PN. Practical use of investigations in patients with hematuria. J Endourol. 2008;22(1):51–56

- Kawashima A, et al. CT urography and MR urography. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41(5):945–961

- Leyendecker JR, Gianini JW. Magnetic resonance urography. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34(4):527–540

- Sadowski EA, Bennett LK, Chan MR, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: risk factors and incidence estimation. Radiology. 2007;243(1):148–157

- Cowan NC, et al. Multidetector computed tomography urography for diagnosing upper urinary tract urothelial tumour. BJU Int. 2007;99(6):1363–1370

- Brown MA, et al. Microscopic hematuria in pregnancy: relevance to pregnancy outcome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):667–673

- Feifer AH, et al. Utility of urine cytology in the workup of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in low-risk patients. Urology. 2010;75(6):1278–1282

- van Rhijn BW, van der Poel HG, van der Kwast TH. Urine markers for bladder cancer surveillance: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2005;47(6):736–748

- Madeb R, Golijanin D, Knopf J, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with a negative work-up for asymptomatic microhematuria. Urology. 2010;75(1):20–25

- Edwards TJ, et al. Patient-specific risk of undetected malignant disease after investigation for haematuria, based on a 4-year follow-up. BJU Int. 2011;107(2):247–252