What is monkeypox

Monkeypox is a rare disease that is caused by infection with monkeypox virus, which is a double-stranded DNA, zoonotic virus (a viral disease that is transmitted from animals to humans) 1. Monkeypox virus (also known as MPXV) belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus in the family Poxviridae 2. The Orthopoxvirus genus also includes variola virus (the cause of smallpox), vaccinia virus (used in the smallpox vaccine), and cowpox virus.

Monkeypox was first discovered in 1958 when two outbreaks of a pox-like disease occurred in colonies of monkeys kept for research, hence the name ‘monkeypox’ 3. The first human case of monkeypox was recorded in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo during a period of intensified effort to eliminate smallpox 4. Monkeypox is a re-emerging viral zoonosis that occurs naturally in heavily forested regions of West and Central Africa 5. Sporadic human monkeypox infections have only been documented three times outside of Africa; in the United States in 2003 (47 cases), and in both the United Kingdom (3 cases) and Israel (1 case) in 2018. In 2003, Gambian giant rats imported from Ghana infected co-habitant prairie dogs sold as household pets in the Midwestern United States 6. This resulted in 53 human cases of monkeypox 6. In October 2018, one case occurred in a man who traveled from Nigeria to Israel 7. In May 2019, one case occurred in a man who traveled from Nigeria to Singapore 8. In May 2021, a family returned to the United Kingdom after traveling to Nigeria, and three family members became infected with the monkeypox virus 9. The sequential timing of symptom development in each case within the family (day 0, day 19, day 33) could represent human-to-human transmission. In July 2021, one case occurred in a man who traveled from Nigeria to Texas 10. In November 2021, one case occurred in a man who traveled from Nigeria to Maryland 11. As of May 2022, one case of human monkeypox in a man who returned to Massachusetts from Canada is under investigation as well as clusters of human monkeypox in the United Kingdom.

There are two distinct genetic strains (clades) of monkeypox virus – Central African clade (also known as Congo Basin clade) and West African clade. Human infections with the Central African monkeypox virus clade (Congo Basin clade) are typically more severe compared to those with the West African virus clade and have a higher mortality 12. Person-to-person spread is well-documented for Central African monkeypox virus (Congo Basin clade) and limited with West African monkeypox 2.

The natural reservoir of monkeypox remains unknown. However, African rodent species are suspected to play a role in transmission 12. Monkeypox infections have occurred in squirrels, rats, mice, monkeys, prairie dogs, and humans 2, 13. Demonstrated risk factors for monkeypox infection are living in heavily forested and rural areas of central and western Africa, handling and preparing bushmeat, caregiving to someone infected with monkeypox virus, and not being vaccinated against smallpox 14, 15. Male gender has also been correlated with infection risk. However, this may be confounded by the cultural norm that men frequently hunt and contact wild animals.

Monkeypox transmission can occur through contact with bodily fluids, skin lesions, or respiratory droplets of infected animals directly or indirectly via contaminated fomites 12. In endemic areas, most sufferers are thought to acquire monkeypox disease from exposure to infected animal carcasses, meat, or blood (animal-to-human transmission). The average age at presentation has increased in the last two decades from 4 to 21 years 16. Monkeypox disease is most frequent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Inter-human transmission of monkeypox virus, although limited, drives outbreaks, particularly in household and health-care settings. But the available evidence suggests that without repeated zoonotic (animal-to-human) transmission, human infections would eventually cease to occur. Therefore, interrupting virus transmission from animals to humans is key to combating this disease.

Monkeypox disease symptoms always involve the characteristic rash similar to that of chickenpox, regardless of whether there is disseminated rash. Historically, the rash has been preceded by a prodrome (early set of symptoms) including fever, enlarged lymph glands (lymphadenopathy), and often other non-specific symptoms such as malaise, headache, and muscle aches. In the most recent reported cases, prodromal symptoms may not have always occurred; some recent cases have begun with characteristic, monkeypox-like lesions in the genital and perianal region, in the absence of subjective fever and other prodromal symptoms. For this reason, cases may be confused with more commonly seen infections (e.g., syphilis, chancroid, herpes, and varicella zoster) 17. Monkeypox disease typically lasts for 2−4 weeks. In Africa, monkeypox has been shown to cause death in as many as 1 in 10 persons who contract monkeypox disease. The case fatality ratio of monkeypox has historically ranged from 0 to 11 % in the general population and has been higher among young children. In recent times, the case fatality ratio has been around 3–6% 18.

At this time, there are no specific treatments available for monkeypox infection, but monkeypox outbreaks can be controlled.

Smallpox vaccine, cidofovir (also known as Vistide), tecovirimat (also known as TPOXX or ST-246) and vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) can be used to control a monkeypox outbreak 19. Brincidofovir (also known as Tembexa) is an antiviral medication that was approved by the FDA on June 4, 2021 for the treatment of human smallpox disease in adult and pediatric patients, including neonates 20. CDC is currently developing an Expanded Access for an Investigational New Drug to help facilitate use of Brincidofovir as a treatment for monkeypox. However, Brincidofovir is not currently available from the Strategic National Stockpile 21.

Figure 1. Monkeypox rash

Footnote: A patient with monkeypox showing characteristic lesions.

[Source 22 ]Figure 2. Monkeypox with a swollen lymph node in the neck

Footnote: Cervical lymphadenopathy in a patient with active monkeypox during a monkeypox outbreak in Zaire, 1996–1997.

[Source 22 ]Figure 3. Monkeypox rash

Footnote: African woman with classical rash of monkeypox virus infection with deep seeded lesions on face, arms, and palms.

[Source 23 ]Figure 4. Monkeypox lesions on hands

[Source 12 ]Figure 5. Monkeypox lesions on palms

[Source 12 ]Figure 6. Monkeypox Cases in endemic countries

[Source 24 ]Table 1. Monkeypox cases since 1970

| Country | Year | Recorded Human Cases* |

|---|---|---|

| Cameroon | 1979 | 2 |

| Cameroon | 1989 | 4 |

| Cameroon | 2018 | 1 |

| Central African Republic | 1984 | 6 |

| Central African Republic | 2001 | 4 |

| Central African Republic | 2010 | 2 |

| Central African Republic | 2015 | 12 |

| Central African Republic | 2016 | 11 |

| Central African Republic | 2017 | 8 |

| Central African Republic | 2018 | 14 |

| Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) | 1971 | 1 |

| Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) | 1981 | 1 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 1970-present | >1000/year † |

| Gabon | 1987 | 5 |

| Israel | 2018 | 1 § |

| Liberia | 1970 | 4 |

| Liberia | 2017 | 2 |

| Nigeria | 1971 | 2 |

| Nigeria | 1978 | 1 |

| Nigeria | 2017-present | 115 ¶ |

| Republic of Congo | 2003 | 11 |

| Republic of Congo | 2009 | 2 |

| Republic of Congo | 2017 | 88 |

| Sierra Leone | 1970 | 1 |

| Sierra Leone | 2014 | 1 |

| Sierra Leone | 2017 | 1 |

| Sudan | 2005 | 19** |

| United Kingdom | 2018 | 3†† |

| United States | 2003 | 47§§ |

Footnotes:

* Includes laboratory-confirmed cases and suspected cases that had an epidemiologic (close contact), spatial, or temporal link to a laboratory-confirmed case

† Democratic Republic of Congo has reported >1,000 suspected cases each year since 2005

§Introduction attributed to an imported case in a traveler who visited Nigeria.

¶ Current as of September 2018. See Nigerian Centre for Disease Control for the most up to date information

** Introduction attributed to movement of the virus from Democratic Republic of the Congo. Cases occurred in an area that is now part of South Sudan

†† Introduction attributed to two unrelated imported cases among travelers who visited Nigeria.

§§ Introduction attributed to a shipment of animals imported from Ghana.

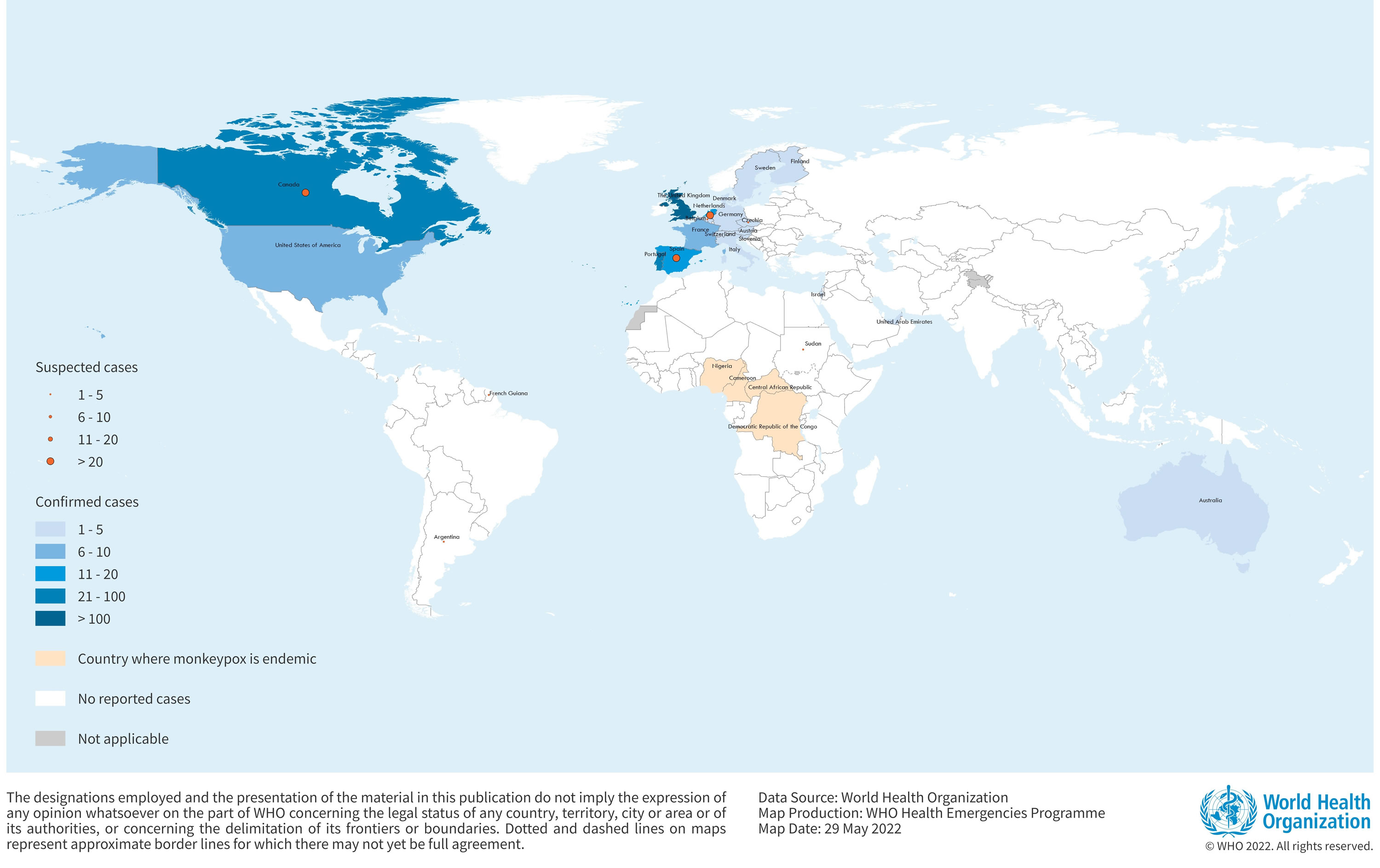

Confirmed cases of monkeypox have been reported in the following countries (as of 26 May 2022) 24:

- Australia – 2 cases

- Austria – 1 cases

- Belgium – 3 cases

- Canada – 26 cases (and 25 to 35 of suspected cases under investigation)

- Czech Republic – 2 cases (and 1 of suspected case under investigation)

- Denmark – 2 cases

- Finland – 1 case

- France – 7 cases

- Germany – 5 cases

- Israel – 1 case

- Italy – 4 cases

- Netherlands – 12 cases (and more than 20 of suspected cases under investigation)

- Portugal – 49 cases

- Slovenia – 2 cases

- Spain – 20 cases (and 64 of suspected cases under investigation)

- Sweden – 2 cases

- Switzerland – 1 case

- United Arab Emirates – 2 case

- United Kingdom and Northern Ireland – 106 cases

- United States – 10 cases

Monkeypox outbreak key points 25, 17, 13:

- Since May 14, 2022, clusters of monkeypox cases, have been reported in several countries that don’t normally have monkeypox. Although previous cases outside of Africa have been associated with travel to endemic countries such as Nigeria, most of the recent cases do not have direct travel-associated exposure risks. None of these people reported having recently been in central or west African countries where monkeypox usually occurs, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria, among others.

- Therefore, the current outbreaks are unusual and different from previous travel-related outbreaks.

- Before May 2022, cases outside of Africa were reported either among people with recent travel to Nigeria or contact with a person with a confirmed monkeypox virus infection. However, in May 2022, nine patients were confirmed with monkeypox in England; six were among persons without a history of travel to Africa and the source of these infections is unknown.

- Some cases were reported among men who have sex with men. Some cases were also reported in people who live in the same household as an infected person.

- Travelers should AVOID:

- Close contact with sick people, including those with skin lesions or genital lesions.

- Contact with dead or live wild animals such as small mammals including rodents (rats, squirrels) and non-human primates (monkeys, apes).

- Eating or preparing meat from wild game (bushmeat) or using products derived from wild animals from Africa (creams, lotions, powders).

- Contact with contaminated materials used by sick people (such as clothing, bedding, or materials used in healthcare settings) or that came into contact with infected animals.

- Risk to the general public is low, but you should seek medical care immediately if you develop new, unexplained skin rash (lesions on any part of the body), with or without fever and chills, and avoid contact with others. If possible, call ahead before going to a healthcare facility. If you are not able to call ahead, tell a staff member as soon as you arrive that you are concerned about monkeypox. Tell your doctor if in the month before developing symptoms:

- You had contact with a person that might have had monkeypox.

- You are a man who has had intimate contact (including sex) with other men.

- You were in an area where monkeypox has been reported (currently, Europe, North America, Australia) or in an area where monkeypox is more commonly found (the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Central African Republic, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Sudan).

- If you are sick and could have monkeypox, delay travel by public transportation until you have been cleared by a healthcare professional or public health officials.

How sick are most people who get monkeypox?

Monkeypox is usually a mild illness that gets better on its own over a number of weeks. Researchers have found that the West African strain of monkeypox is responsible for the current outbreak. That’s good news, because the death rate from this strain is much lower than the Central African clade (Congo Basin clade) (about 1% to 3% versus 11%) 2. More severe illness may occur in children, pregnant people, or people with immune suppression.

Do I need to be worried about catching monkeypox?

No. Monkeypox has always been considered a rare sporadic disease with a limited capacity to spread between humans 26. The overall risk for the public and health care providers is low at this time 27. Human-to-human transmission can result from close contact with respiratory secretions, skin lesions of an infected person or recently contaminated objects. Transmission via droplet respiratory particles usually requires prolonged face-to-face contact, which puts health workers, household members and other close contacts of active cases at greater risk. However, the longest documented chain of transmission in a community has risen in recent years from 6 to 9 successive person-to-person infections. This may reflect declining immunity in all communities due to cessation of smallpox vaccination. Transmission can also occur via the placenta from mother to fetus (which can lead to congenital monkeypox) or during close contact during and after birth. While close physical contact is a well-known risk factor for transmission, it is unclear at this time if monkeypox can be transmitted specifically through sexual transmission routes. Studies are needed to better understand this risk.

The public isn’t considered at high risk for several reasons. First, transmission of monkeypox requires prolonged close contact with people who are infected. Unlike COVID-19, where people may not know they are infected, people infected with monkeypox have symptoms, such as fever or a rash, that make it easier to recognize. These symptoms cause people to seek out medical care.

The incubation period — the time from when a person is exposed to when that person develops symptoms — is long. Therefore, public health measures can help prevent additional cases.

People who may have symptoms of monkeypox should contact their healthcare provider. This includes anyone who:

- traveled to central or west African countries, parts of Europe where monkeypox cases have been reported, or other areas with confirmed cases of monkeypox during the month before their symptoms began,

- reports contact with a person with confirmed or suspected monkeypox, or

- is a man who regularly has close or intimate contact with other men, including men who meet partners through an online website, digital application or at a bar or party.

Finally, vaccines can prevent infection. Treatments are available for those who get infected.

Can I get vaccinated for monkeypox now?

No, vaccinations for monkeypox are not available to the public. In the event of exposure, public health authorities will guide vaccination of close contacts, including health care workers.

What causes monkeypox

Monkeypox is caused by the monkeypox virus also known as MPXV. There are two main strains (clades) of monkeypox virus, one more virulent and transmissible the Congo Basin clade (also known as the Central African clade) than the other the West African clade. The less virulent West African clade has been identified among the current cases. The reservoir host is still unknown, although rodents are suspected to play a part in the endemic setting.

These two monkeypox virus strains (the Congo Basin strain [Central African strain] and the West African strain) are geographically separated and have defined epidemiological and clinical differences. The West African strain demonstrates a case fatality rate <1%, and no human-to-human transmission was ever documented 2. In comparison, the Congo Basin strain (also known as the Central African clade) show a case fatality rate up to 11% and documented human-to-human transmission up to 6 sequential events was observed 28. The isolates from the West African clade originated from outbreaks in Nigeria, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, and USA (imported from Ghana) while the isolates belonging to the Central African clade came from Gabon, Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo 29. According to available data, the Congo Basin clade (Central African clade) is more common than the West African clade given it is endemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where more than 2,000 suspected cases are reported every year 30. However, monkeypox is not part of mandatory reporting in other countries than the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which might introduce a bias 31.

Currently (May 2022) it’s not clear how the people outside of Africa were exposed to monkeypox, but cases include people who self-identify as men who have sex with men.

Following viral entry from any route (oropharynx, nasopharynx, or intradermal), the monkeypox virus replicates at the inoculation site then spreads to local lymph nodes. Next, an initial viremia leads to viral spread and seeding of other organs. This represents the incubation period and typically lasts 7 to 14 days with an upper limit of 21 days.

Symptom onset correlates with a secondary viremia leading to 1 to 2 days of prodromal symptoms such as fever and lymphadenopathy before lesions appear. Infected patients may be contagious at this time. Lesions start in the oropharynx then appear on the skin. Serum antibodies are often detectable by the time lesions appear 32.

Monkeypox transmission

Transmission of monkeypox virus occurs when a person comes into contact with the monkeypox virus from an infected animal, infected person or materials contaminated with the monkeypox virus 1. Monkeypox virus enters the body through broken skin (even if not visible), respiratory tract, or the mucous membranes (eyes, nose, or mouth). Animal-to-human transmission may occur by bite or scratch of an infected animal, handling bush meat (wild game), direct contact with body fluids or lesion material, through the use of products made from infected animals or indirect contact with lesion material, such as through contaminated bedding. Human-to-human transmission is thought to occur primarily through direct contact with infectious sores, scabs, or body fluids. Monkeypox virus can also be spread by respiratory secretions during prolonged, face-to-face contact. Monkeypox can spread during intimate contact between people, including during oral, anal, and vaginal sex, as well as activities like kissing, cuddling, or touching parts of the body with monkeypox sores. At this time, it is not known if monkeypox can spread through semen or vaginal fluids. Other human-to-human methods of transmission include indirect contact with lesion material, such as through contaminated clothing or linens. The monkeypox virus can also cross the placenta from the mother to her fetus.

It is not yet known what animal (the reservoir host or main disease carrier) maintains the monkeypox virus in nature, although African rodents are suspected to play a part in monkeypox transmission to people. Various animal species have been identified as susceptible to monkeypox virus, this includes rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, dormice, non-human primates and other species 18.

The virus that causes monkeypox has only been recovered (isolated) twice from an animal in nature. In the first instance (1985), the virus was recovered from an apparently ill African rodent (rope squirrel) in the Equator Region of the Democratic Republic of Congo. In the second (2012), the virus was recovered from a dead infant mangabey found in the Tai National Park, Cote d’Ivoire.

In 29 peer-reviewed articles, attempts were made to establish the mode of transmission for confirmed, probable, and/or possible monkeypox cases 16. The transmission details, by country, including number of cases and mode of transmission, are summarized in a table here https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141.s006

A study from the 1980s involving 338 monkeypox cases from the Democratic Republic of Congo concluded that an animal source was suspected in 72.5% (245/338) of cases and a human source in 27.5% (93/338) of cases 33. In contrast, in an investigation of 419 cases from the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1990s, only 22% were primary cases (i.e., a person who reported no contact with another person with monkeypox), while 78% were secondary cases (i.e., monkeypox in a person who had contact with an infected person 7–21 days before onset of disease) 34. Data from the Nigerian outbreak (Sept 2017-Sept 2018) found that transmission was unknown for 62.3% (76/122) of cases 35. Of the remaining 46 cases, 36 or 78.3% had an epidemiological link to people with similar lesions before the onset of monkeypox and 10 or 8.2% reported contact with animals 35.

All but one of the monkeypox cases outside of Africa were the result of confirmed or suspected animal-to-human transmission 8. This exception was a human-to-human transmission in the UK in a healthcare worker who provided care to one of the UK confirmed monkeypox cases 36.

The risk factors or risk behaviors for contracting monkeypox were reported in only five studies from three countries [Democratic Republic of Congo 37, 38, 39, US 40, Republic of the Congo 41], and in general reinforced what has been suspected factors. For example, sleeping in the same room or bed, living in the same household, or drinking or eating from the same dish were risk behaviors associated with human-to-human transmission 39. On the other hand, sleeping outside or on the ground or living near or visiting the forest were identified as factors that increase the risk for exposure to animals and subsequent risk for animal-to-human transmission of monkeypox 41. Unexpectedly, assisting with toileting and hygiene and laundering clothes did not have a significant association with acquiring monkeypox, and preparing wild animal for consumption or eating duiker (a small to medium-sized brown antelope native to sub-Saharan Africa) were identified as protective factors 39. After adjusting for smallpox vaccination status, daily exposure to sick animals or cleaning their cages/bedding were identified as risk factors for acquiring monkeypox in the 2003 outbreak in the US 40. Touching or been scratched by an infected animal sufficient to sustain a break in skin were each found to be both significant and nonsignificant risk factors 40.

Monkeypox prevention

There are number of measures that can be taken to prevent infection with monkeypox virus 42:

- Avoid contact with animals that could harbor the virus (including animals that are sick or that have been found dead in areas where monkeypox occurs).

- Avoid contact with any materials, such as bedding, that has been in contact with a sick animal.

- Isolate infected patients from others who could be at risk for infection.

- Practice good hand hygiene after contact with infected animals or humans. For example, washing your hands with soap and water or using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

- Use personal protective equipment when caring for patients.

JYNNEOS (also known as Imvamune or Imvanex) is an attenuated live virus vaccine which has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of monkeypox 43. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is currently evaluating JYNNEOS for the protection of people at risk of occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses such as smallpox and monkeypox in a pre-event setting.

Monkeypox vaccine (smallpox vaccine)

Because monkeypox virus is closely related to the virus that causes smallpox, the smallpox vaccine can protect people from getting monkeypox. Past data from Africa suggests that the smallpox vaccine is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox. Experts also believe that vaccination after a monkeypox exposure may help prevent the disease or make it less severe.

Smallpox vaccine is not currently available to the general public. In the event of another outbreak of monkeypox in the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will establish guidelines explaining who should be vaccinated.

The Strategic National Stockpile has three smallpox vaccines 44:

- ACAM2000® and JYNNEOS (also known as Imvamune or Imvanex) are the only two licensed smallpox vaccines in the United States.

- Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APSV) is an investigational vaccine that may be used in a smallpox emergency under the appropriate regulatory mechanism (i.e., Investigational New Drug application [IND] or Emergency Use Authorization [EUA]).

JYNNEOS (also known as Imvamune or Imvanex), has been licensed in the United States to prevent monkeypox and smallpox. The effectiveness of JYNNEOS (Imvamune or Imvanex) against monkeypox was concluded from a clinical study on the immunogenicity of JYNNEOS and efficacy data from animal studies. Experts also believe that vaccination after a monkeypox exposure may help prevent the disease or make it less severe.

ACAM2000, which contains a live vaccinia virus, is licensed for immunization in people who are at least 18 years old and at high risk for smallpox infection. It can be used in people exposed to monkeypox if used under an expanded access investigational new drug protocol.

ACAM2000®

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has licensed ACAM2000® (Smallpox [Vaccinia] Vaccine, Live), a replication-competent vaccine, for active immunization against smallpox disease in persons determined to be at high risk for smallpox infection 45. The vaccine does not contain variola virus and cannot cause smallpox. It contains vaccinia virus, which belongs to the poxvirus family, genus Orthopoxvirus. The vaccinia virus may cause rash, fever, and head and body aches. In certain groups of people, particularly those who are immunocompromised, complications from the vaccinia virus can be severe.

Replication-competent smallpox vaccine consists of a live, infectious vaccinia virus that can be transmitted from the vaccine recipient to unvaccinated persons who have close contact with the inoculation site, or with exudate from the site. The risk of side effects in household contacts is the same as those for the vaccine recipient. Therefore, the vaccination site requires special care to prevent the virus from spreading.

ACAM2000® is administered as a single dose by the percutaneous route using the multiple puncture technique.

The 2015 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations advise routine vaccination of laboratory personnel who directly handle cultures of, or animals infected with 46:

- Replication-competent vaccinia virus

- Recombinant vaccinia viruses derived from replication-competent vaccinia strains (i.e., those that are capable of causing clinical infection and producing infectious virus in humans), or

- Other orthopoxviruses that can infect humans (e.g., monkeypox, cowpox, and variola)

Routine vaccination is not recommended for, but should be offered to 44:

- Healthcare personnel (e.g., physicians, nurses) who currently treat or anticipate treating patients with vaccinia virus infections

- Anyone administering ACAM2000®

In the event of a smallpox emergency, ACAM2000® would be made available to persons exposed to smallpox virus or who are at high risk of smallpox infection, depending on the circumstances of the event.

Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine

Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APSV) is another replication-competent vaccinia virus vaccine in the Strategic National Stockpile, with a safety profile anticipated to be similar to ACAM2000®. It is an investigational vaccine. In a smallpox emergency, Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APSV) would be made available under an Investigational New Drug application [IND] or Emergency Use Authorization [EUA] for use in circumstances where ACAM2000® is depleted, not readily available, or in a case-by-case basis where ACAM2000® is contraindicated.

Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APSV) is also administered by the same multiple puncture technique as ACAM2000®.

APSV is administered in a single dose (~2.5 uL) by the percutaneous route (scarification) using 15 jabs of a stainless steel bifurcated needle that has been dipped into the vaccine 47. The site of vaccination is the upper arm over the deltoid muscle. Studies of undiluted vaccine potency found a titer of 10 x 107.6 plaque-forming units (PFU)/mL and there was no difference in vaccine success rates when comparing diluted (1:5) and undiluted vaccine 48. Yearly monitoring of APSV potency remains ongoing.

Vaccine is provided in 0.25 mL aliquots in sterile 2 mL glass vials. Each vial must be further diluted with the appropriate companion diluent to achieve the 1:5 dilution specified in the current pre-EUA filed with FDA. For a 1:5 dilution to be achieved, 1 mL of diluent must be added to one vial of APSV, which will yield approximately 500 doses of vaccine per vial.

Imvamune or Imvanex

The FDA has licensed Imvamune or Imvanex (JYNNEOSTM), a replication-deficient smallpox vaccine, for the prevention of smallpox and monkeypox. Unlike ACAM2000® and Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APSV), Imvamune or Imvanex (JYNNEOSTM) is an attenuated live virus vaccine.

As a replication-deficient vaccine, it can be used for vaccination of people 18 years and older with certain immune deficiencies or conditions, such as HIV or atopic dermatitis. JYNNEOS has been studied in people with HIV and atopic dermatitis and no severe adverse events were identified. The specific use of JYNNEOS in a smallpox emergency will be based on risk of exposure and relative contraindications to ACAM2000®.

Unlike ACAM2000® and APSV, JYNNEOS is administered subcutaneously as two doses separated by 4 weeks (one dose at week 0 and a second dose at week 4) for primary vaccinees (individuals who have never been vaccinated against smallpox or do not recall receiving a smallpox vaccination in the past) 43. Individuals previously vaccinated against smallpox receive one dose.

Monkeypox signs and symptoms

In humans, the symptoms of monkeypox are similar to but milder than the symptoms of smallpox. The early symptoms of monkeypox are flulike, and include fever, headache, muscle aches, exhaustion and enlarged lymph nodes. The main difference between symptoms of smallpox and monkeypox is that monkeypox causes lymph nodes to swell (lymphadenopathy) while smallpox does not. Swelling of the lymph nodes may be generalized (involving many different locations on the body) or localized to several areas (e.g., neck and armpit).

Monkeypox infection can be divided into two periods:

- The invasion period (lasts between 0–5 days) characterized by fever, intense headache, lymphadenopathy (swelling of the lymph nodes), back pain, myalgia (muscle aches) and intense asthenia (lack of energy). Lymphadenopathy is a distinctive feature of monkeypox compared to other diseases that may initially appear similar (chickenpox, measles, smallpox)

- The skin eruption usually begins within 1–3 days of appearance of fever. The rash tends to be more concentrated on the face and extremities rather than on the trunk. It affects the face (in 95% of cases), and palms of the hands and soles of the feet (in 75% of cases). Also affected are oral mucous membranes (in 70% of cases), genitalia (30%), and conjunctivae (20%), as well as the cornea. The rash evolves sequentially from macules (lesions with a flat base) to papules (slightly raised firm lesions), vesicles (lesions filled with clear fluid), pustules (lesions filled with yellowish fluid), and crusts which dry up and fall off. The number of lesions varies from a few to several thousand. In severe cases, lesions can coalesce until large sections of skin slough off.

Monkeypox is usually a self-limited disease with the symptoms lasting from 2 to 4 weeks.

Although the disease is usually mild, complications can include pneumonia, vision loss due to eye infection, and sepsis, a life-threatening infection.

Severe cases occur more commonly among children and are related to the extent of virus exposure, patient health status and nature of complications. Underlying immune deficiencies may lead to worse outcomes. Although vaccination against smallpox was protective in the past, today persons younger than 40 to 50 years of age (depending on the country) may be more susceptible to monkeypox due to cessation of smallpox vaccination campaigns globally after eradication of the disease. Complications of monkeypox can include secondary infections, bronchopneumonia, sepsis, encephalitis, and infection of the cornea with ensuing loss of vision. The extent to which asymptomatic infection may occur is unknown.

Monkeypox Incubation period

Infection with monkeypox virus begins with an incubation period. The incubation period (time from infection to symptoms) for monkeypox is usually 7−14 days but can range from 5−21 days 49. A person is not contagious during the incubation period. A person does not have symptoms and may feel fine.

Monkeypox Prodrome

Persons with monkeypox will develop an early set of symptoms (prodrome). A person may sometimes be contagious during this period 49.

Monkeypox illness begins with:

- Fever

- Headache

- Muscle aches

- Backache

- Swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy)

- Lymphadenopathy is a distinguishing feature of monkeypox from smallpox.

- This typically occurs with fever onset, 1–2 days before rash onset, or rarely with rash onset.

- Lymph nodes may swell in the neck (submandibular & cervical), armpits (axillary), or groin (inguinal) and occur on both sides of the body or just one.

- Lymphadenopathy is a distinguishing feature of monkeypox from smallpox.

- Chills

- Exhaustion

- Sometimes sore throat and cough

Within 1 to 3 days (sometimes longer) after the appearance of fever, the patient develops a rash, often beginning on the face then spreading to other parts of the body.

Monkeypox Rash

Monkeypox rash that appears a few days later following the prodrome is unique. It often starts in the mouth, on the face and then appears on the palms, arms, legs, and other parts of the body. Some recent cases began with a rash on the genitals. Over a week or two, the rash changes from small, flat spots to tiny blisters (vesicles) similar to chickenpox, and then to larger, pus-filled blisters. These can take several weeks to scab over before falling off. Once that happens, the person is no longer contagious.

A person is contagious from the onset of the enanthem through the scab stage 49.

Skin lesions progress through the following stages before falling off:

- Macules

- Papules

- Vesicles

- Pustules

- Scabs

Table 2. Monkeypox Rash Enanthem Through the Scab Stage

| Stage | Stage Duration | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Enanthem |

| |

| Macules | 1−2 days |

|

| Papules | 1−2 days |

|

| Vesicles | 1−2 days |

|

| Pustules | 5−7 days |

|

| Scabs | 7−14 days |

|

Monkeypox Rash resolved

Pitted scars and/or areas of lighter or darker skin may remain after scabs have fallen off. Once all scabs have fallen off a person is no longer contagious 49.

Monkeypox complications

Monkeypox complications may include 50:

- Bacterial superinfection of skin

- Permanent skin scarring

- Hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation

- Permanent corneal scarring (vision loss)

- Pneumonia

- Dehydration (vomiting, diarrhea, decreased oral intake due to painful oral lesions, and insensible fluid loss from widespread skin disruption)

- Sepsis

- Encephalitis

- Death

Monkeypox diagnosis

Possible human cases of monkeypox should be reported to your local hospital epidemiologist and/or infection control personnel, who will contact your state health department. If appropriate, the state health department will contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Consultation with the state epidemiologist, state health laboratory, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is necessary before sending specimens to CDC.

Personnel who collect specimens should use personal protective equipment in accordance with recommendations for standard, contact, and droplet precautions. Specimens should be collected in the manner outlined below. When possible, use plastic rather than glass materials for specimen collection.

Table 3. The following types of specimens should be collected in accordance with stage of monkeypox

| Disease Phase | Specimens to Collect |

|---|---|

| Prodrome | Tonsillar tissue swab Nasopharyngeal swab Acute serum and whole blood |

| Rash* | |

| Macules or Papules | Tonsillar tissue swab Lesion biopsy Acute serum and whole blood |

| Vesicles or Pustules | Lesion fluid, roof, or biopsy Electron microscopy grid (if supplies available) Acute serum and whole blood |

| Scabs or Crusts | Lesion scab or crust Acute serum and whole blood |

| Post-Rash | Convalescent serum |

Footnote: * More than one lesion should be sampled, preferably from different locations on the body and/or from different looking lesions.

Tonsillar Tissue Swab Collection

Materials needed:

- 2—Sterile screw-capped plastic tube with O-ring (1.5 to 2 mL)

- 2—Sterile dry polyester or Dacron swabs

Procedure:

- Swab or brush posterior tonsillar tissue with a sterile dry polyester or Dacron swab.

- Break off end of applicator into a 1.5 or 2 mL screw-capped tube with O-ring or place entire swab in a sterile container. DO NOT ADD ANY VIRAL TRANSPORT MEDIA.

Nasopharyngeal Swab Collection

Materials needed:

- 2—Sterile screw-capped plastic tube with O-ring (1.5 to 2 mL)

- 2—Sterile dry polyester or Dacron swabs

Procedure:

- Swab the nasopharynx with a sterile dry polyester or Dacron swab.

- Break off end of applicator into a 1.5 or 2 mL screw-capped tube with O-ring or place entire swab in a sterile container. DO NOT ADD ANY VIRAL TRANSPORT MEDIA.

Lesion Biopsy Collection

Materials needed:

- 1—Punch biopsy kit (2.5 mm for pediatrics; 3.5 or 4 mm for adults)

- 1—Needle driver

- 1—Sutures

- 1—Suture removal kit

- 1—Container of 10% neutral buffered formalin

- 2—Sterile screw-capped plastic tube with O-ring (1.5 to 2 mL)

- Multiple—Alcohol wipes

Procedure:

- Use appropriate sterile technique and skin sanitation.

- Biopsy 2 lesions with 3.5 or 4 mm biopsy punch (2.5 mm for pediatrics).

- Place one biopsy specimen in formalin.

- Place one biopsy specimen in a 1.5 to 2 mL screw-capped plastic vial with O-ring. DO NOT ADD ANY VIRAL TRANSPORT MEDIA.

Lesion Fluid Collection

Lesion fluid can be collected by swab, smear or touch prep slides. In addition, if electron microscopy materials are available this type of specimen collection can also be used.

Lesion Fluid Swab

Materials needed:

- 2—Disposable scalpel with no. 10 blade, or

- 2—26 Gauge needle

- 4—Sterile screw-capped plastic vials with O-ring (1.5 to 2 mL)

- 4–8—Sterile dry polyester or Dacron swabs

- Multiple—Alcohol wipes

Procedure:

- Sanitize lesion with an alcohol wipe, allow to dry.

- Use a disposable scalpel (or a sterile 26 Gauge needle) to open, and remove, the top of the vesicle or pustule (do not send the scalpel or needle). Retain lesion roof for testing.

- Swab the base of the lesion with a sterile polyester or Dacron swab.

- Break off end of applicator into a 1.5 or 2 mL screw-capped tube with O-ring or place entire swab in a sterile container. DO NOT ADD ANY VIRAL TRANSPORT MEDIA.

Lesion Fluid Smear or Touch Prep Slide

Materials needed:

- 2—Disposable scalpel with no. 10 blade, or

- 2—26 Gauge needle

- 4—Clean plastic or glass microscope slides

- 4—Plastic single-slide holders

- 4–8—Sterile dry polyester or Dacron swabs (if needed)

- Multiple—Alcohol wipes

- Parafilm (optional)

Procedure:

- Sanitize lesion with an alcohol wipe, allow to dry.

- Use a disposable scalpel (or a sterile 26 Gauge needle) to open, and remove, the top of the vesicle or pustule (do not send the scalpel or needle). Retain lesion roof for testing.

- Scrape the base of the vesicle or pustule with the blunt edge of the scalpel, or with the end of an applicator stick or swab.

- Smear the scrapings onto a clean microscope slide.

- Apply a microscope slide to the vesicular or pustular fluid multiple times, with progressive movement of the slide, to make a touch prep.

- Allow slides and grids to air dry for approximately 10 minutes.

- Store slides from different patients in separate plastic slide holders to prevent cross-contamination (parafilm may be used to wrap the slide holder to prevent accidental opening).

Electron Microscopy Grid

Materials needed:

- 2—Disposable scalpel with no. 10 blade, or

- 2—26 Gauge needle

- 2–4—Formvar/carbon-coated mesh electron microscopy grids

- 1—Electron microscopy quality forceps

- 1—Electron microscopy grid box

- Multiple—Alcohol wipes

Procedure:

- Sanitize lesion with an alcohol wipe, allow to dry.

- Use a disposable scalpel (or a sterile 26 Gauge needle) to open, and remove, the top of the vesicle or pustule (do not send the scalpel or needle). Retain lesion roof for testing.

- Lightly touch the “shiny side” of an electron microscope grid to the unroofed base of the lesion.

- Repeat this procedure two more times, varying the pressure applied to the unroofed lesion (lighter or firmer pressure).

- Place in grid box and record which slot is used for each patient specimen.

Lesion Roof Collection

Materials needed:

- 2—Disposable scalpel with no. 10 blade, or

- 2—26 Gauge needle

- 4—Sterile screw-capped plastic vials with O-ring (1.5 to 2 mL)

- Multiple— Alcohol wipes

Procedure:

- Sanitize lesion with an alcohol wipe, allow to dry.

- Use a disposable scalpel (or a sterile 26 Gauge needle) to open, and remove, the top of the vesicle or pustule (do not send the scalpel or needle).

- Place the skin of the vesicle top into a 1.5 to 2 mL sterile screw-capped plastic tube with O-ring. DO NOT ADD ANY VIRAL TRANSPORT MEDIA.

Scab or Crust Collection

Materials needed:

- 1—26 Gauge needle

- 2—Sterile screw-capped plastic vials with O-ring (1.5 to 2 mL)

- Multiple—Alcohol wipes

Procedure:

- Sanitize skin with an alcohol wipe, allow to dry.

- Use a 26 Gauge needle to pick or dislodge at least 4 scabs; two scabs each from at least two body locations

- Place scabs from each location in separate sterile O-ring vials.

Acute/Convalescent Serum and Whole Blood Collection

Materials needed:

- 1—5 or 10 cc syringe with needle

- 1—Vacutainer holder

- 2—Vacutainer needles

- 1—10 cc red/gray, gold, or red-topped serum separator tube for serum collection

- 1—Lavender-topped tube (potassium EDTA) for whole blood collection

Blood Collection Procedure:

- Collect 7 to 10 cc of patient blood into a red/gray (marbled), gold, or red topped serum separator tube when patient is first identified.

- Spin tubes to separate serum.

- Save the serum in at least 2 aliquots, 1 for immediate testing and the other for paired sera testing at the convalescent –stage of disease.

- Collect 3 to 5 cc of whole blood into a lavender-topped tube.

- Gently invert the tube to mix the blood with the anticoagulant.

- Obtain convalescent-phase serum 4 to 6 weeks after initial acute-phase serum collection.

- Send convalescent-phase serum with the remaining acute-phase serum aliquot.

Post-Collection Procedures

- After specimen collection is completed, PPE worn by the specimen collector should be removed.

- Disposable equipment (e.g., gown, gloves, mask) should be placed in a biohazard bag for disposal with other medical waste.

- Reusable equipment (e.g., goggles, faceshield) should be disinfected and set aside for reprocessing. If cloth gowns are used, they should be placed in a bag with other contaminated linens in the patient’s room.

- Needles and other sharp instruments should be placed in a sharps container.

- Contaminated waste generated during specimen collection should be handled in accordance with existing facility procedures and local or state regulations for regulated medical waste.

- Each specimen should be labeled with the patient’s name, collection date, type of specimen, and body location for lesion specimens.

- Specimens, excluding formalin fixed specimens and EM grids, may be stored at 4⁰C or -70⁰C if shipping is expected to occur >24 hours after collection. Formalin fixed specimens and EM grids may be stored at 4⁰C. These types of specimens should never be frozen.

- Place specimens from a single patient into a biohazard bag labeled with the patient’s name and date of birth.

- Blood tubes should be placed in individual Styrofoam holders.

- All specimens, excluding those in formalin, should be shipped on gel packs at 4⁰C. Formalin fixed specimens should be shipped at room temperature.

- Specimens should be packaged and shipped in accordance with IATA rules and regulations for diagnostic specimens (UN 3373).

Monkeypox treatment

Many individuals infected with monkeypox virus have a mild, self-limiting disease course in the absence of specific therapy. The prognosis for monkeypox depends on multiple factors such as previous vaccination status, initial health status, concurrent illnesses, and comorbidities among others. Persons who should be considered for treatment following consultation with CDC might include 21:

- Persons with severe disease (e.g., hemorrhagic disease, confluent lesions, sepsis, encephalitis, or other conditions requiring hospitalization)

- Persons who may be at high risk of severe disease:

- Persons with immunocompromise (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome infection, leukemia, lymphoma, generalized malignancy, solid organ transplantation, therapy with alkylating agents, antimetabolites, radiation, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, high-dose corticosteroids, being a recipient with hematopoietic stem cell transplant <24 months post-transplant or ≥24 months but with graft-versus-host disease or disease relapse, or having autoimmune disease with immunodeficiency as a clinical component) 51

- Pediatric populations, particularly patients younger than 8 years of age 52

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women 53

- Persons with one or more complications (e.g., secondary bacterial skin infection; gastroenteritis with severe nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, or dehydration; bronchopneumonia; concurrent disease or other comorbidities) 54

- Persons with monkeypox virus aberrant infections that include its accidental implantation in eyes, mouth, or other anatomical areas where monkeypox virus infection might constitute a special hazard (e.g., the genitals or anus)

Currently, there is no proven, safe treatment for monkeypox virus infection. For purposes of controlling a monkeypox outbreak in the United States, smallpox vaccine, antivirals, and vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) can be used 55.

Clinical care

Treatment for monkeypox is mainly supportive. The illness is usually mild and most of those infected will recover within a few weeks without treatment. But as the infection can spread through close contact, it’s important to isolate if you’re diagnosed with monkeypox. The infected individual should remain in isolation, wear a surgical mask, and keep lesions covered as much as reasonably possible until all lesion crusts have naturally fallen off and a new skin layer has formed.

If your symptoms are severe or you’re at higher risk of getting seriously ill (for example, if you have a weakened immune system), you may need to stay in a specialist hospital until you recover.

You may be offered a vaccination to reduce the risk of getting seriously ill.

- Skin care:

- Wash skin lesions with soap and water or povidone-iodine solution

- Treat secondary bacterial infections with topical or oral antibiotics as needed

- Eye care:

- Prevent corneal scarring and visual impairment with vitamin A supplementation especially for children as it plays an important role in all stages of wound healing and eye health

- Protective eye pads and ophthalmic antibiotics or antivirals as needed

- Mouth care:

- Wash mouth with warm clean salted water

- Use oral analgesic medication to minimize mucosal pain from mouth sores and encourage food and fluid intake

Tecovirimat (ST-246 or TPOXX)

Tecovirimat also known as TPOXX or ST-246, is an antiviral medication that is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of human smallpox disease in adults and pediatric patients weighing at least 3 kg 56. The CDC holds an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug Protocol (EA-IND) that allows for the use of Tecovirimat for the treatment of non-variola orthopoxviruses (including monkeypox) in an outbreak 21. This protocol includes allowance for opening an oral capsule of tecovirimat and mixing its content with semi-solid food for pediatric patients weighing less than 13 kg. Tecovirimat is available as oral (200 mg capsule) and injection for intravenous formulations.

Data is not available on the effectiveness of tecovirimat (ST-246 or TPOXX) in treating human cases of monkeypox.

Studies using a variety of animal species have shown that tecovirimat (ST-246) is effective in treating orthopoxvirus-induced disease. Human clinical trials indicated the drug was safe and tolerable with only minor side effects.

Although currently stockpiled by the Strategic National Stockpile, use of tecovirimat (ST-246) is administered under an Investigational New Drug application [IND].

Cidofovir and Brincidofovir (Tembexa)

Cidofovir also known as Vistide, is an antiviral medication that is approved by the FDA for the treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) 57. The CDC holds an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug Protocol (EA-IND) that allows for the use of Cidofovir for the treatment of orthopoxviruses (including monkeypox) in an outbreak 21.

Brincidofovir also known as Tembexa, is an antiviral medication that was approved by the FDA on June 4, 2021 for the treatment of human smallpox disease in adult and pediatric patients, including neonates 20. The CDC is currently developing an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug Protocol (EA-IND) to help facilitate use of Brincidofovir as a treatment for monkeypox. However, Brincidofovir is not currently available from the Strategic National Stockpile.

Data is not available on the effectiveness of Cidofovir (Vistide) and Brincidofovir (Tembexa) in treating human cases of monkeypox. However, both have proven activity against poxviruses in in vitro and animal studies.

It is unknown whether or not a person with severe monkeypox infection will benefit from treatment with either antiviral, although their use may be considered in such instances. Brincidofovir may have an improved safety profile over Cidofovir. Serious renal toxicity or other adverse events have not been observed during treatment of cytomegalovirus infections with Brincidofovir as compared to treatment using Cidofovir.

Vaccinia Immune Globulin (VIG)

Vaccinia Immune Globulin Intravenous (VIGIV) is licensed by FDA for the treatment of complications due to vaccinia vaccination including eczema vaccinatum, progressive vaccinia, severe generalized vaccinia, vaccinia infections in individuals who have skin conditions, and aberrant infections induced by vaccinia virus (except in cases of isolated keratitis) 58. The CDC holds an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug Protocol (EA-IND) that allows the use of VIGIV for the treatment of orthopoxviruses (including monkeypox) in an outbreak 21.

Data is not available on the effectiveness of vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) in treatment of monkeypox complications. Use of vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) is administered under an IND and has no proven benefit in the treatment of smallpox complications. It is unknown whether a person with severe monkeypox infection will benefit from treatment with vaccinia immune globulin (VIG), however, its use may be considered in such instances.

Vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) can be considered for prophylactic use in an exposed person with severe immunodeficiency in T-cell function for which smallpox vaccination following exposure to monkeypox is contraindicated.

Monkeypox prognosis

There are two distinct strain or clades of the monkeypox virus. The West African clade has a more favorable prognosis with a case fatality rate below 1%. On the other hand, the Central African clade (Congo Basin clade) is more lethal, with a case fatality rate of up to 11% in unvaccinated children. Aside from potential scarring and discoloration of the skin, the remainder of patients typically fully recover within four weeks of symptom onset 2.

References- Monkeypox. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/

- Sklenovská, N., & Van Ranst, M. (2018). Emergence of Monkeypox as the Most Important Orthopoxvirus Infection in Humans. Frontiers in public health, 6, 241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00241

- Cho, C. T., & Wenner, H. A. (1973). Monkeypox virus. Bacteriological reviews, 37(1), 1–18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC413801/pdf/bactrev00040-0009.pdf

- Ladnyj, I. D., Ziegler, P., & Kima, E. (1972). A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 46(5), 593–597. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2480792/pdf/bullwho00192-0028.pdf

- Reynolds MG, Doty JB, McCollum AM, Olson VA, Nakazawa Y. Monkeypox re-emergence in Africa: a call to expand the concept and practice of One Health. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17(2):129–139. doi:10.1080/14787210.2019.1567330 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6438170

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Multistate outbreak of monkeypox–Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003 Jun 13;52(23):537-40. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5223a1.htm

- Erez, N., Achdout, H., Milrot, E., Schwartz, Y., Wiener-Well, Y., Paran, N., Politi, B., Tamir, H., Israely, T., Weiss, S., Beth-Din, A., Shifman, O., Israeli, O., Yitzhaki, S., Shapira, S. C., Melamed, S., & Schwartz, E. (2019). Diagnosis of Imported Monkeypox, Israel, 2018. Emerging infectious diseases, 25(5), 980–983. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2505.190076

- Yong, S., Ng, O. T., Ho, Z., Mak, T. M., Marimuthu, K., Vasoo, S., Yeo, T. W., Ng, Y. K., Cui, L., Ferdous, Z., Chia, P. Y., Aw, B., Manauis, C. M., Low, C., Chan, G., Peh, X., Lim, P. L., Chow, L., Chan, M., Lee, V., … Leo, Y. S. (2020). Imported Monkeypox, Singapore. Emerging infectious diseases, 26(8), 1826–1830. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2608.191387

- Hobson, G., Adamson, J., Adler, H., Firth, R., Gould, S., Houlihan, C., Johnson, C., Porter, D., Rampling, T., Ratcliffe, L., Russell, K., Shankar, A. G., & Wingfield, T. (2021). Family cluster of three cases of monkeypox imported from Nigeria to the United Kingdom, May 2021. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin, 26(32), 2100745. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.32.2100745

- Rao, A. K., Schulte, J., Chen, T. H., Hughes, C. M., Davidson, W., Neff, J. M., Markarian, M., Delea, K. C., Wada, S., Liddell, A., Alexander, S., Sunshine, B., Huang, P., Honza, H. T., Rey, A., Monroe, B., Doty, J., Christensen, B., Delaney, L., Massey, J., … July 2021 Monkeypox Response Team (2022). Monkeypox in a Traveler Returning from Nigeria – Dallas, Texas, July 2021. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 71(14), 509–516. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7114a1

- Costello, V., Sowash, M., Gaur, A., Cardis, M., Pasieka, H., Wortmann, G., & Ramdeen, S. (2022). Imported Monkeypox from International Traveler, Maryland, USA, 2021. Emerging infectious diseases, 28(5), 1002–1005. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2805.220292

- Moore M, Zahra F. Monkeypox. [Updated 2022 May 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574519

- Update 77 – Monkeypox outbreak, update and advice for health workers. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/risk-comms-updates/update_monkeypox-.pdf

- Rimoin, A. W., Mulembakani, P. M., Johnston, S. C., Lloyd Smith, J. O., Kisalu, N. K., Kinkela, T. L., Blumberg, S., Thomassen, H. A., Pike, B. L., Fair, J. N., Wolfe, N. D., Shongo, R. L., Graham, B. S., Formenty, P., Okitolonda, E., Hensley, L. E., Meyer, H., Wright, L. L., & Muyembe, J. J. (2010). Major increase in human monkeypox incidence 30 years after smallpox vaccination campaigns cease in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(37), 16262–16267. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1005769107

- Petersen, B. W., Kabamba, J., McCollum, A. M., Lushima, R. S., Wemakoy, E. O., Muyembe Tamfum, J. J., Nguete, B., Hughes, C. M., Monroe, B. P., & Reynolds, M. G. (2019). Vaccinating against monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Antiviral research, 162, 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.11.004

- Bunge, E. M., Hoet, B., Chen, L., Lienert, F., Weidenthaler, H., Baer, L. R., & Steffen, R. (2022). The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox-A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 16(2), e0010141. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141

- Monkeypox Virus Infection in the United States and Other Non-endemic Countries—2022. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2022/han00466.asp

- Monkeypox. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- Monkeypox Treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/treatment.html

- FDA approves drug to treat smallpox. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-drug-treat-smallpox

- Interim Clinical Guidance for the Treatment of Monkeypox. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/treatment.html

- Andrea M. McCollum, Inger K. Damon, Human Monkeypox, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 58, Issue 2, 15 January 2014, Pages 260–267, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit703

- Weaver, J. R., & Isaacs, S. N. (2008). Monkeypox virus and insights into its immunomodulatory proteins. Immunological reviews, 225, 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00691.x

- Multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries: Update. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON388

- Monkeypox in Multiple Countries. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/alert/monkeypox

- The current status of human monkeypox: memorandum from a WHO meeting. (1984). Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 62(5), 703–713. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2536211/pdf/bullwho00094-0031.pdf

- Questions and answers about monkeypox. https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/questions-and-answers-about-monkeypox

- Z. Ježek, M. Szczeniowski, K. M. Paluku, M. Mutombo, Human Monkeypox: Clinical Features of 282 Patients, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 156, Issue 2, August 1987, Pages 293–298, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/156.2.293

- Sbrana E, Xiao SY, Newman PC, Tesh RB. Comparative pathology of North American and central African strains of monkeypox virus in a ground squirrel model of the disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Jan;76(1):155-64.

- Mwamba DK, Kebela BI, Shongo RL, Pukuta E, Kayembe NJM. Profil épidemiologique du monkeypox en RDC, 2010-2014. Ann African Med. (2014) 8:1855–60. https://anafrimed.net/profil-epidemiologique-du-monkeypox-en-rdc-2010-2014-monkeypox-in-drc-epidemiological-profile-2010-2014/

- Durski, K. N., McCollum, A. M., Nakazawa, Y., Petersen, B. W., Reynolds, M. G., Briand, S., Djingarey, M. H., Olson, V., Damon, I. K., & Khalakdina, A. (2018). Emergence of Monkeypox – West and Central Africa, 1970-2017. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 67(10), 306–310. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6710a5

- Hutson, C. L., Carroll, D. S., Gallardo-Romero, N., Drew, C., Zaki, S. R., Nagy, T., Hughes, C., Olson, V. A., Sanders, J., Patel, N., Smith, S. K., Keckler, M. S., Karem, K., & Damon, I. K. (2015). Comparison of Monkeypox Virus Clade Kinetics and Pathology within the Prairie Dog Animal Model Using a Serial Sacrifice Study Design. BioMed research international, 2015, 965710. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/965710

- Jezek, Z., Grab, B., Szczeniowski, M., Paluku, K. M., & Mutombo, M. (1988). Clinico-epidemiological features of monkeypox patients with an animal or human source of infection. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 66(4), 459–464. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2491168/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human monkeypox — Kasai Oriental, Democratic Republic of Congo, February 1996-October 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997 Dec 12;46(49):1168-71 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00050245.htm

- Yinka-Ogunleye A, Aruna O, Dalhat M, Ogoina D, McCollum A, Disu Y, Mamadu I, Akinpelu A, Ahmad A, Burga J, Ndoreraho A, Nkunzimana E, Manneh L, Mohammed A, Adeoye O, Tom-Aba D, Silenou B, Ipadeola O, Saleh M, Adeyemo A, Nwadiutor I, Aworabhi N, Uke P, John D, Wakama P, Reynolds M, Mauldin MR, Doty J, Wilkins K, Musa J, Khalakdina A, Adedeji A, Mba N, Ojo O, Krause G, Ihekweazu C; CDC Monkeypox Outbreak Team. Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017-18: a clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Aug;19(8):872-879. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30294-4

- Vaughan, A., Aarons, E., Astbury, J., Brooks, T., Chand, M., Flegg, P., Hardman, A., Harper, N., Jarvis, R., Mawdsley, S., McGivern, M., Morgan, D., Morris, G., Nixon, G., O’Connor, C., Palmer, R., Phin, N., Price, D. A., Russell, K., Said, B., … Dunning, J. (2020). Human-to-Human Transmission of Monkeypox Virus, United Kingdom, October 2018. Emerging infectious diseases, 26(4), 782–785. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2604.191164

- Fuller, T., Thomassen, H. A., Mulembakani, P. M., Johnston, S. C., Lloyd-Smith, J. O., Kisalu, N. K., Lutete, T. K., Blumberg, S., Fair, J. N., Wolfe, N. D., Shongo, R. L., Formenty, P., Meyer, H., Wright, L. L., Muyembe, J. J., Buermann, W., Saatchi, S. S., Okitolonda, E., Hensley, L., Smith, T. B., … Rimoin, A. W. (2011). Using remote sensing to map the risk of human monkeypox virus in the Congo Basin. EcoHealth, 8(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-010-0355-5

- Jezek, Z., Grab, B., Szczeniowski, M. V., Paluku, K. M., & Mutombo, M. (1988). Human monkeypox: secondary attack rates. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 66(4), 465–470. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2491159

- Nolen, L. D., Osadebe, L., Katomba, J., Likofata, J., Mukadi, D., Monroe, B., Doty, J., Kalemba, L., Malekani, J., Kabamba, J., Bomponda, P. L., Lokota, J. I., Balilo, M. P., Likafi, T., Lushima, R. S., Tamfum, J. J., Okitolonda, E. W., McCollum, A. M., & Reynolds, M. G. (2015). Introduction of Monkeypox into a Community and Household: Risk Factors and Zoonotic Reservoirs in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 93(2), 410–415. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0168

- Reynolds, M. G., Davidson, W. B., Curns, A. T., Conover, C. S., Huhn, G., Davis, J. P., Wegner, M., Croft, D. R., Newman, A., Obiesie, N. N., Hansen, G. R., Hays, P. L., Pontones, P., Beard, B., Teclaw, R., Howell, J. F., Braden, Z., Holman, R. C., Karem, K. L., & Damon, I. K. (2007). Spectrum of infection and risk factors for human monkeypox, United States, 2003. Emerging infectious diseases, 13(9), 1332–1339. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1309.070175

- Guagliardo, S., Doshi, R. H., Reynolds, M. G., Dzabatou-Babeaux, A., Ndakala, N., Moses, C., McCollum, A. M., & Petersen, B. W. (2020). Do Monkeypox Exposures Vary by Ethnicity? Comparison of Aka and Bantu Suspected Monkeypox Cases. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 102(1), 202–205. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.19-0457

- Monkeypox Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/prevention.html

- https://www.fda.gov/media/131078/download

- https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/vaccines.html

- ACAM2000. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/acam2000

- Petersen BW, Harms TJ, Reynolds MG, Harrison LH. Use of Vaccinia Virus Smallpox Vaccine in Laboratory and Health Care Personnel at Risk for Occupational Exposure to Orthopoxviruses — Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:257–262. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6510a2

- Clinical Guidance for Smallpox Vaccine Use in a Postevent Vaccination Program. Recommendations and Reports February 20, 2015 / 64(RR02);1-26. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6402a1.htm?s_cid=rr6402a1_w

- Talbot TR, Stapleton JT, Brady RC, et al. Vaccination Success Rate and Reaction Profile With Diluted and Undiluted Smallpox Vaccine: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2004;292(10):1205–1212. doi:10.1001/jama.292.10.1205

- Monkeypox Clinical Recognition. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html

- Reynolds, M. G., McCollum, A. M., Nguete, B., Shongo Lushima, R., & Petersen, B. W. (2017). Improving the Care and Treatment of Monkeypox Patients in Low-Resource Settings: Applying Evidence from Contemporary Biomedical and Smallpox Biodefense Research. Viruses, 9(12), 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/v9120380

- Petersen BW, Harms TJ, Reynolds MG, Harrison LH. Use of Vaccinia Virus Smallpox Vaccine in Laboratory and Health Care Personnel at Risk for Occupational Exposure to Orthopoxviruses – Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Mar 18;65(10):257-62. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6510a2

- Jezek Z, Szczeniowski M, Paluku KM, Mutombo M. Human monkeypox: clinical features of 282 patients. J Infect Dis. 1987 Aug;156(2):293-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.2.293

- Cono, J., Cragan, J. D., Jamieson, D. J., & Rasmussen, S. A. (2006). Prophylaxis and treatment of pregnant women for emerging infections and bioterrorism emergencies. Emerging infectious diseases, 12(11), 1631–1637. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1211.060618

- Dimie Ogoina, Michael Iroezindu, Hendris Izibewule James, Regina Oladokun, Adesola Yinka-Ogunleye, Paul Wakama, Bolaji Otike-odibi, Liman Muhammed Usman, Emmanuel Obazee, Olusola Aruna, Chikwe Ihekweazu, Clinical Course and Outcome of Human Monkeypox in Nigeria, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 71, Issue 8, 15 October 2020, Pages e210–e214, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa143

- Monkeypox Treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/treatment.html

- https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214518s000lbl.pdf

- https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/1999/020638s003lbl.pdf

- https://www.fda.gov/media/78174/download