Mullein

Mullein also known as Great Mullein, Common Mullein (Verbascum thapsus L., Verbascum densiflorum Bertol. or Verbascum thapsiforme Schrad), “Bullock’s Lungwort” or Irish Mullein Weed, is a medicinal plant readily found in roadsides, railroads, fence rows, meadows and pasture lands and has been used to treat pulmonary problems, inflammatory diseases, asthma, spasmodic coughs, diarrhea and migraine headaches 1, 2. Mullein is a biennial herb native to Europe, north Africa, the Azores, the Madeira Islands, Canary Islands, Europe, the Middle-East, western and northern Asia, and the Indian Sub-continent 3. Once established, Mullein exhibits vigorous growth and threatens native plants in meadows and forest gaps 4. Each individual can produce 100,000-175,000 seeds that can remain viable for more than 100 years, making established populations of Mullein (Verbascum thapsus) difficult to eradicate 5.

Common mullein (Verbascum species) has been widely used in Spanish folk medicine to treat pathologies related to the musculature, skeleton, and circulatory, digestive, and respiratory systems, as well as to treat infectious diseases and organ-sense illnesses 6. Today, the dried mullein leaves and flowers, swallow capsules, alcohol extracts and the mullein flower oil can easily be found in health stores in the United States 7. The dried mullein flowers and preparations that are obtained by drying and comminuting (reducing into tiny pieces) the mullein flowers. These mullein flower medicines are usually available as herbal tea to be drunk. These mullein flower medicines may also be found in combination with other herbal substances in some herbal medicines. Modern day European complimentary medicine frequently hails mullein flower oil as a remedy for earache 8. Trials have shown a statistically significant improvement in ear pain associated with acute otitis media (acute middle ear infection) when treated with the Naturopathic Herbal Extract Ear Drops (containing abstracts of the herbs: garlic [0.05%], common mullein [25%], common marigold [28%], St. John’s wort [30%], lavender [5%] and vitamin E [2%] in olive oil [10%]) 9.

Mullein is a species of eudicot (flowering plants mainly characterized by having two seed leaves upon germination) in the family Scrophulariaceae (figwort family). This botanical family took its name from Scrophularia or figwort—a typical member of the family which was used to treat the tuberculous infection of the lymph nodes of the neck known as scrofula 10. This name was in turn derived from the Latin scrofa, meaning “breeding sow” 11. The connection may be because the glands associated with the disease resemble the body of a sow or because pigs were thought to be prone to the disease 11.

The results of qualitative phytochemical screening showed that mullein (Verbascum thapsus) is a rich source of biologically active compounds that may be useful in the treatment of various diseases 12. Numerous studies in the laboratory confirmed that the extract of Mullein plant has anti-inflammatory properties 13, antibacterial 14, anti-virus 15, analgesic 16 and sedative properties 17. Toxic effects of mullein have not been reported in any of the studies 18.

The chemical structure of mullein (Verbascum thapsus) contains substances such as tannins, alkaloids, and saponins, polysaccharides, and flavonoids, each of which can be responsible for wound healing activities 19. The flavonoids and polysaccharides in mullein (Verbascum thapsus) cause the proliferation of fibroblasts and connective tissue in test tube studies, which causes a significant effect of the Verbascum in the process of healing incisional and excisional wounds 20.

Verbascoside exhibited anti-inflammatory properties 21, whereas luteolin and saponin induced apoptosis of A549 lung cancer cells 22. Researchers also concluded that Verbascoside in mullein flowers has an anesthetic and analgesic effect 23. The experimental test tube study by Akdemir 23 in two groups of the mullein flower ointment and control showed that mullein flower has significant activity in wound healing, pain relief, and anti-inflammatory properties. In the study by Taleb et al. 24, the effect of the Verbascum cream on episiotomy pain in 100 nulliparous women was investigated and the results were analyzed on days 1, 3, and 10 after the study. The data obtained from the study showed that the mullein cream has a significant effect on reducing the pain intensity score compared to the placebo group in the studied days 24.

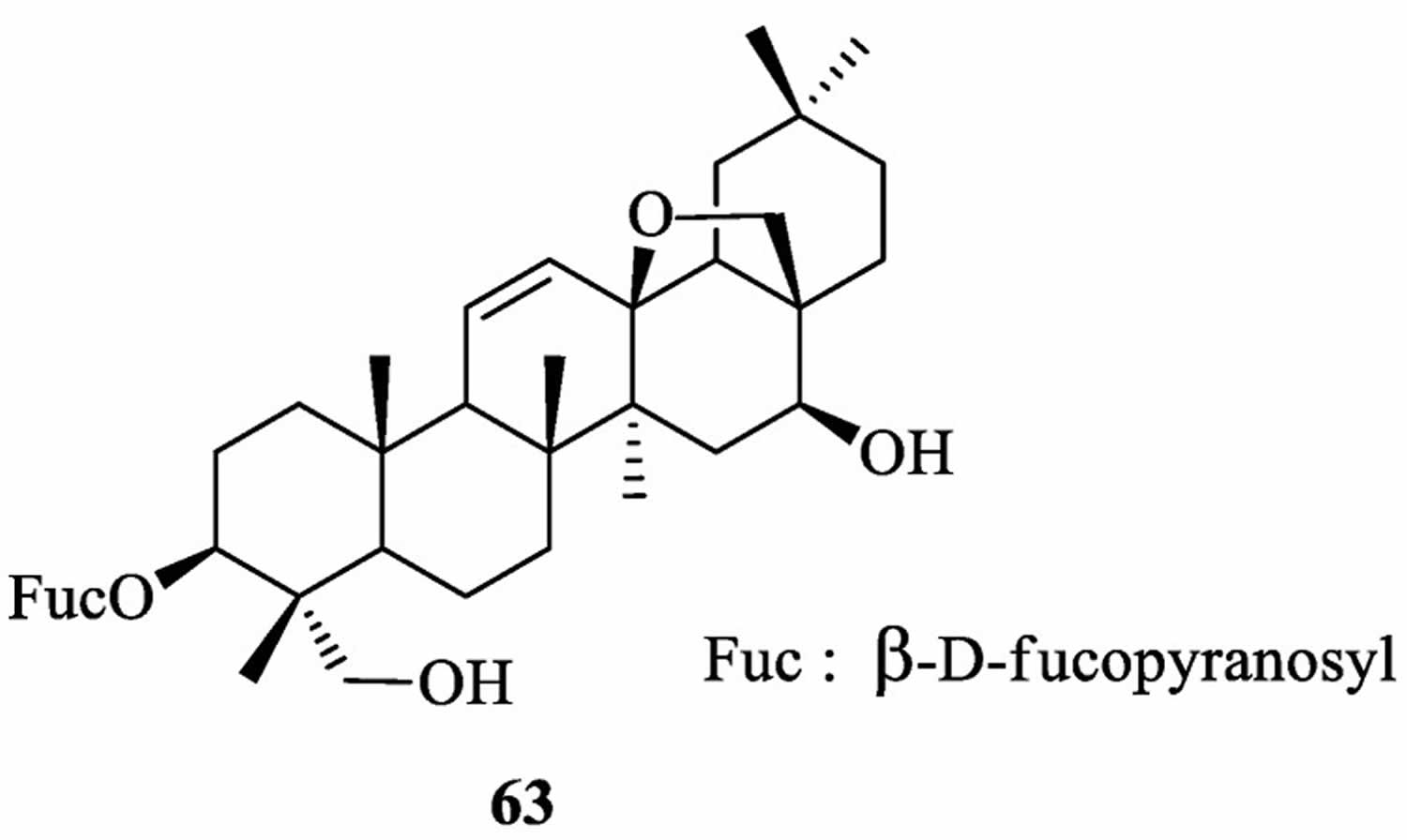

Saponins are also a major chemical constituent of mullein. Sterones and saponins include 24α-methyl-5α-cholestan-3-one, 24-ξ-ethyl-5α-cholestan-22-en-3-one, 24-ξ-ethyl-5β-cholestan-22-en-3-one, 24-ξ-ethyl-5α-cholestan-7-en-3-one, 24α-ethyl-5α-cholestan-Δ7,22-dien-3-one, 24-ξ-ethyl-5α-cholestan-3-one, 24-ξ-ethyl-5β-cholestan-3-one 25 and 3-O-fucopyranosylsaikogenin F (63) 22. This diverse class of compounds are derived from a 30-carbon precursor and perform a range of biological actions. While previous studies have shown weak antimicrobial activity and often only at low cell density 26, some of the most promising activities have been against mycobacteria 27.

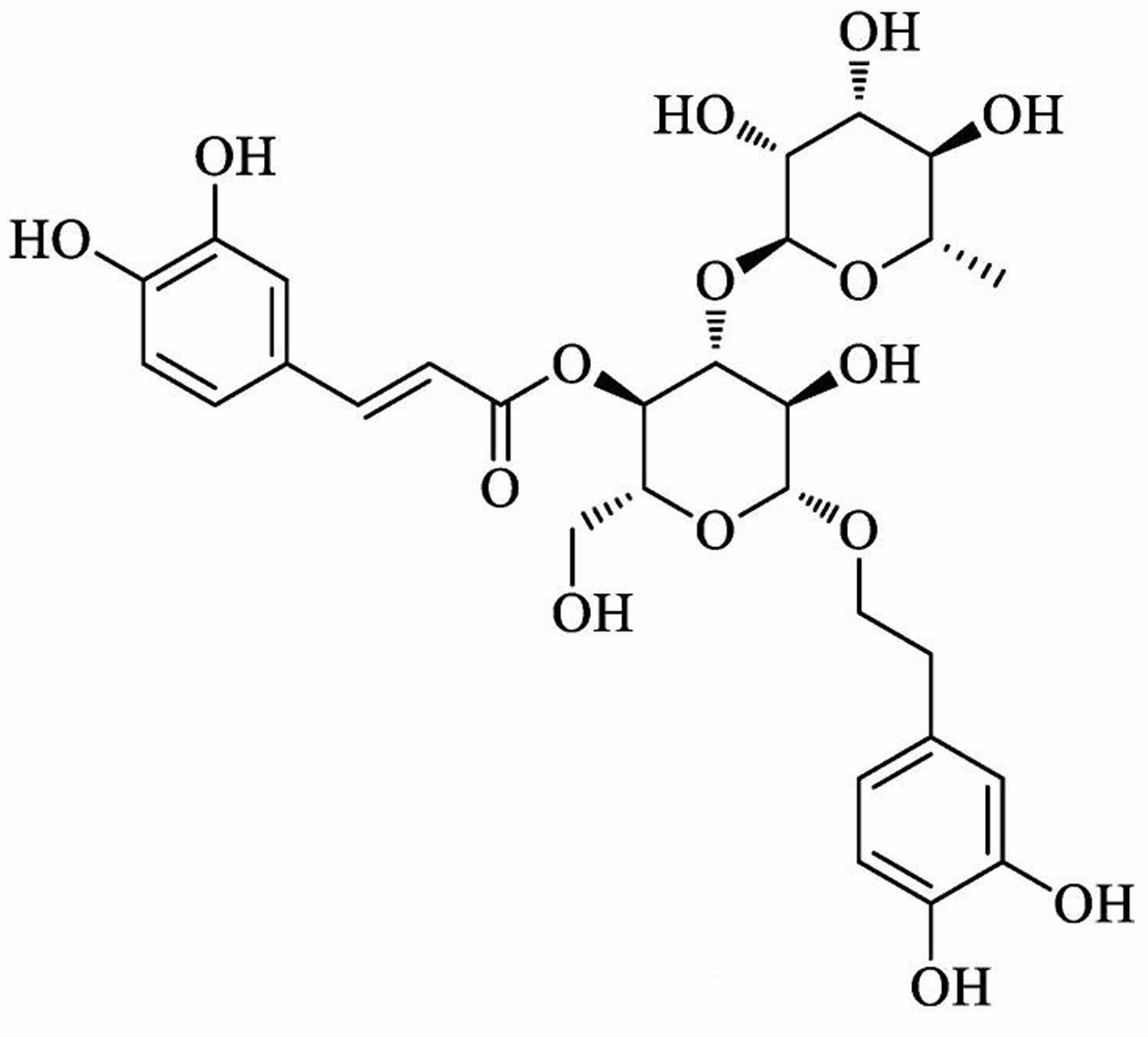

Figure 1. Verbascoside from mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

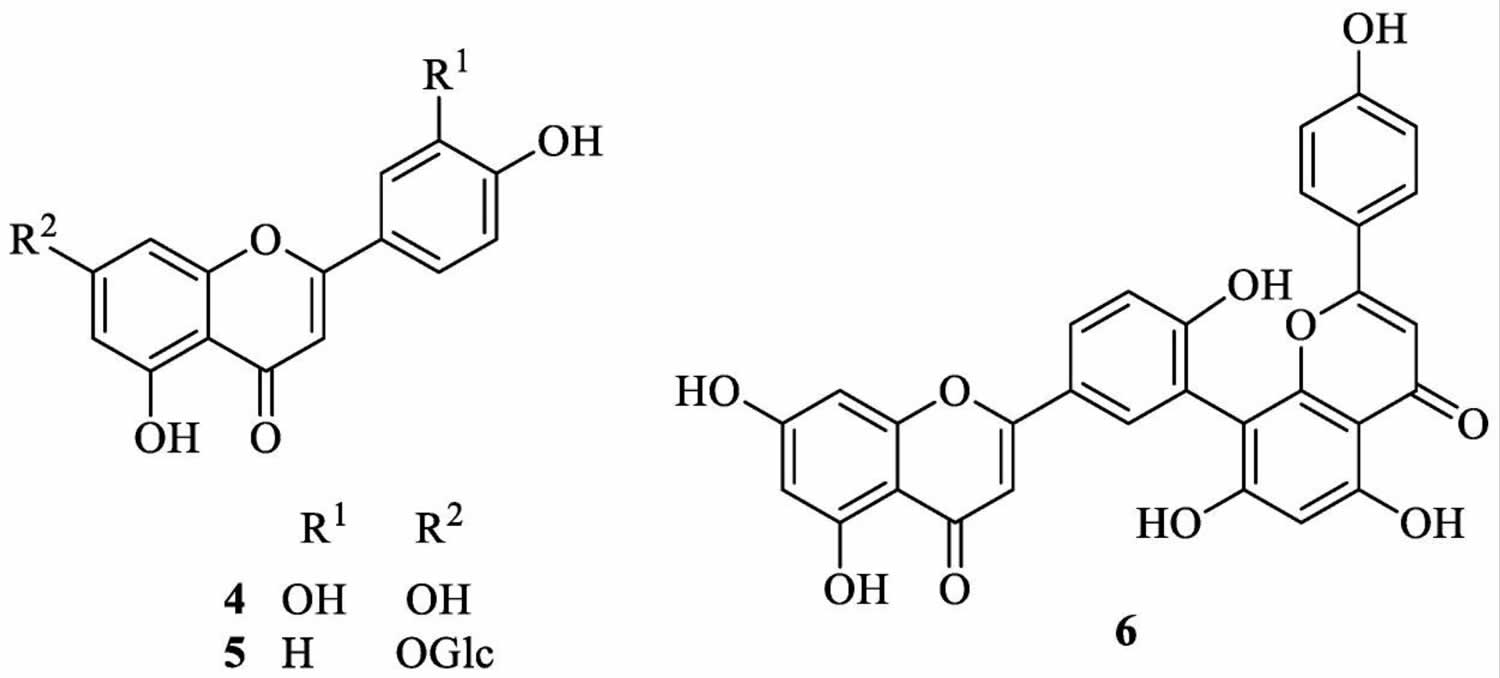

[Source 28 ]Figure 2. Flavonoids isolated from mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

Footnotes: Luteolin (4), apigetrin (apigenin 7-O-glucoside) (5), 5-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoyl(1→3)-[β-D-glucuronopyranosyl-1→6)]-β-D-glucopyranosyl luteolin and the dimer amentoflavone (6).

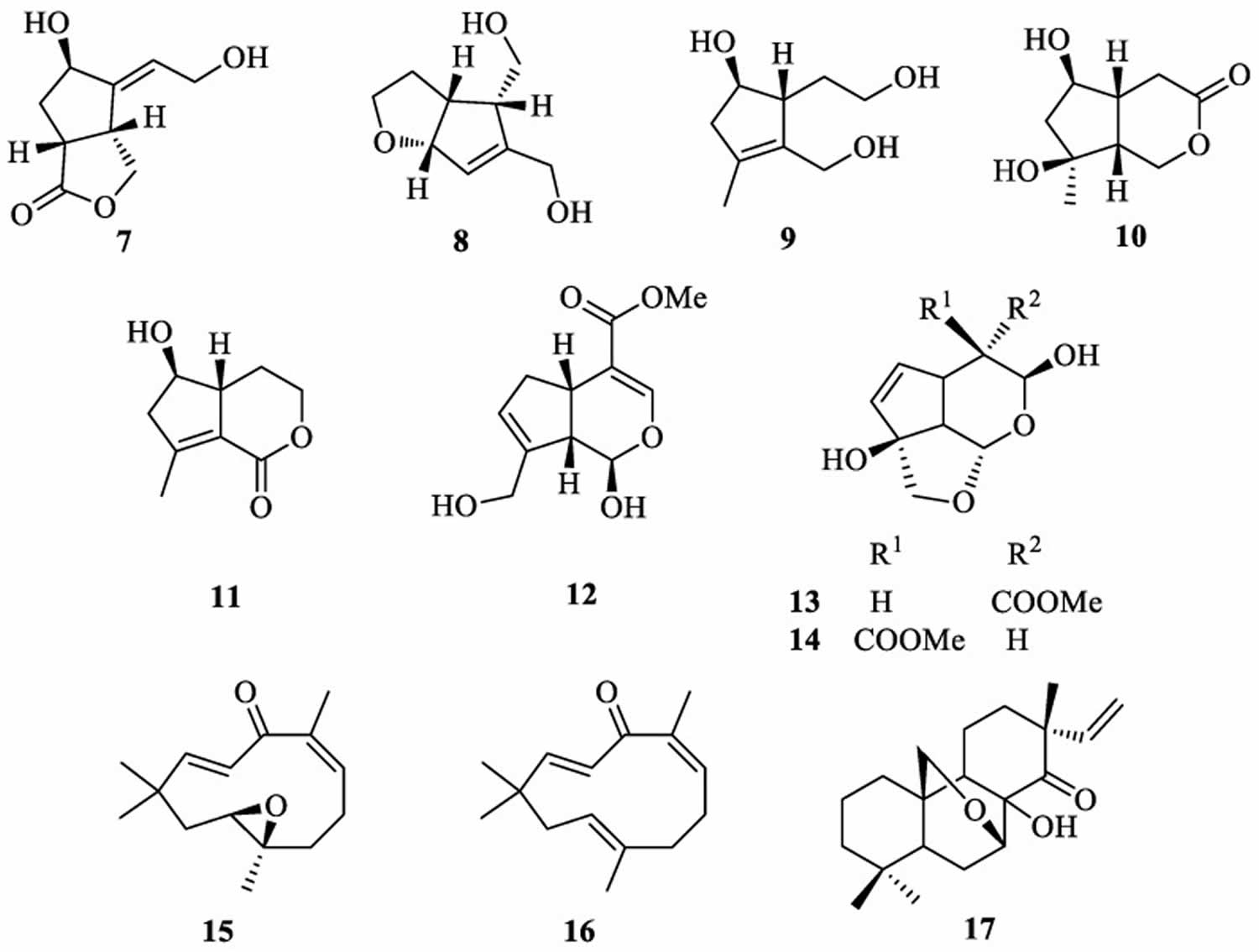

[Source 28 ]Figure 3. Iridoids and terpenes isolated from mullein

Footnotes: Verbathasin A (7), ningpogenin (8), 10-deoxyeucommiol (9), jioglutolide (10), 6β-hydroxy-2-oxabicyclo[4.3.0]Δ8-9-nonen-1-one (11), (+)-genipin (12), α-gardiol (13) and β-gardiol (14). Other characteristic terpenoids are buddlindeterpene A-C (15–17) and 3α-hydroxy-drimmanyl-8-methanoate.

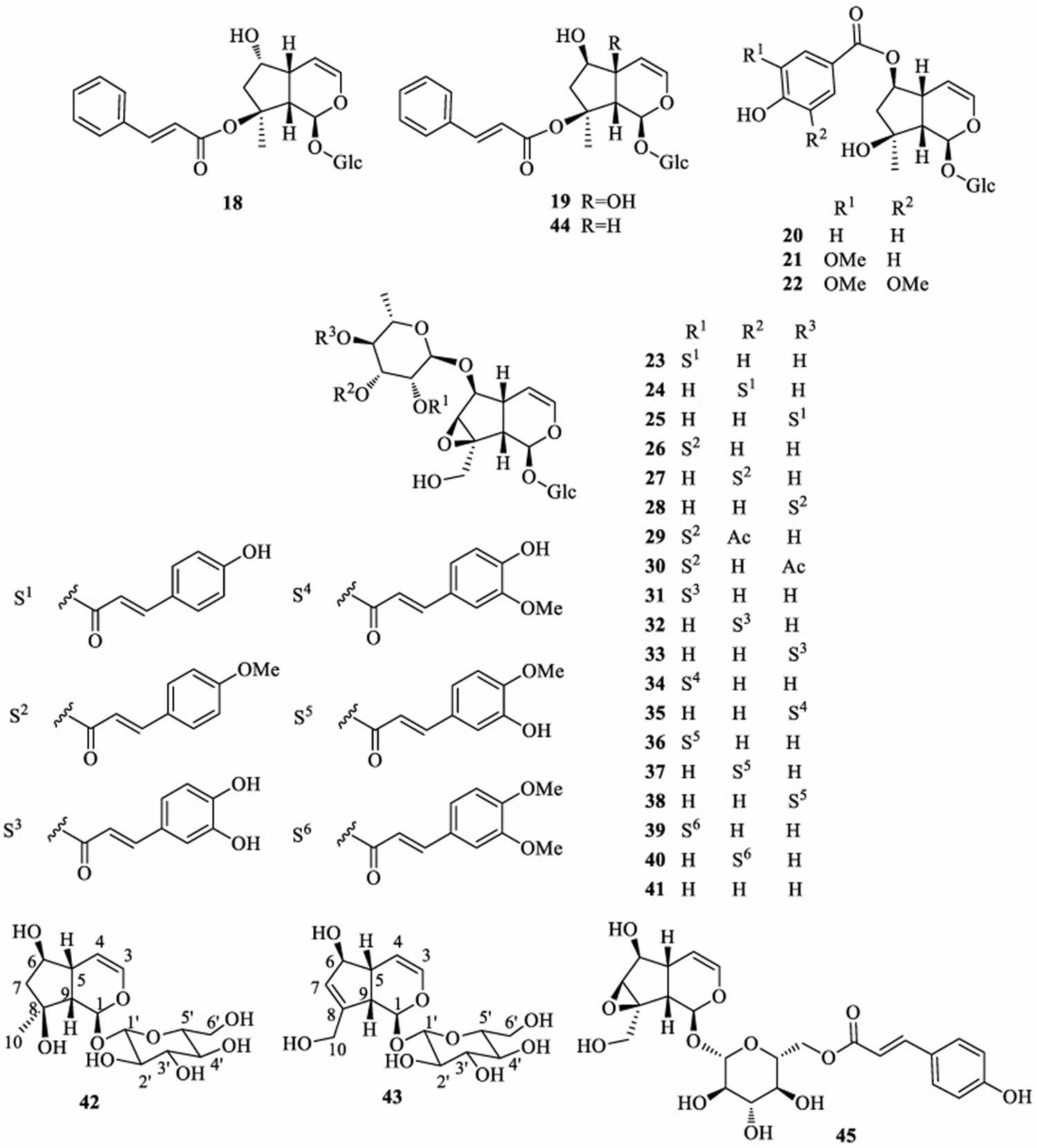

[Source 28 ]Figure 4. Iridoid glycosides isolated from mullein

Footnotes: Iridoid glycosides include lateroside (18), harpagoside (19), compounds 20–41, ajugol (42), aucubin (43), 6-O-β-xyloxyl aucubin, 8-cinnamoylmyoporoside (44) and picroside IV (45).

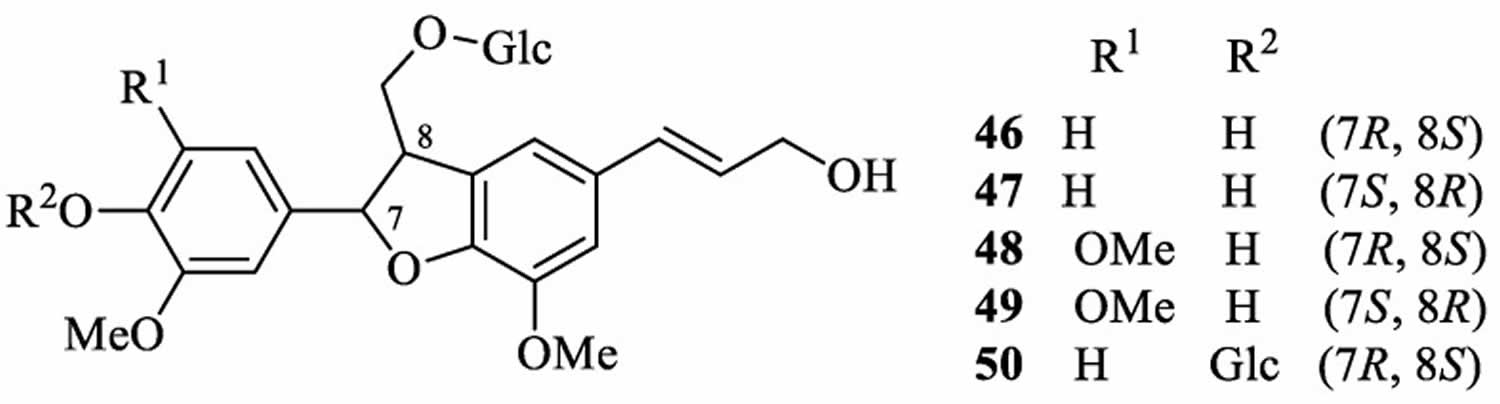

[Source 28 ]Figure 5. Lignan glycosides isolated from mullein

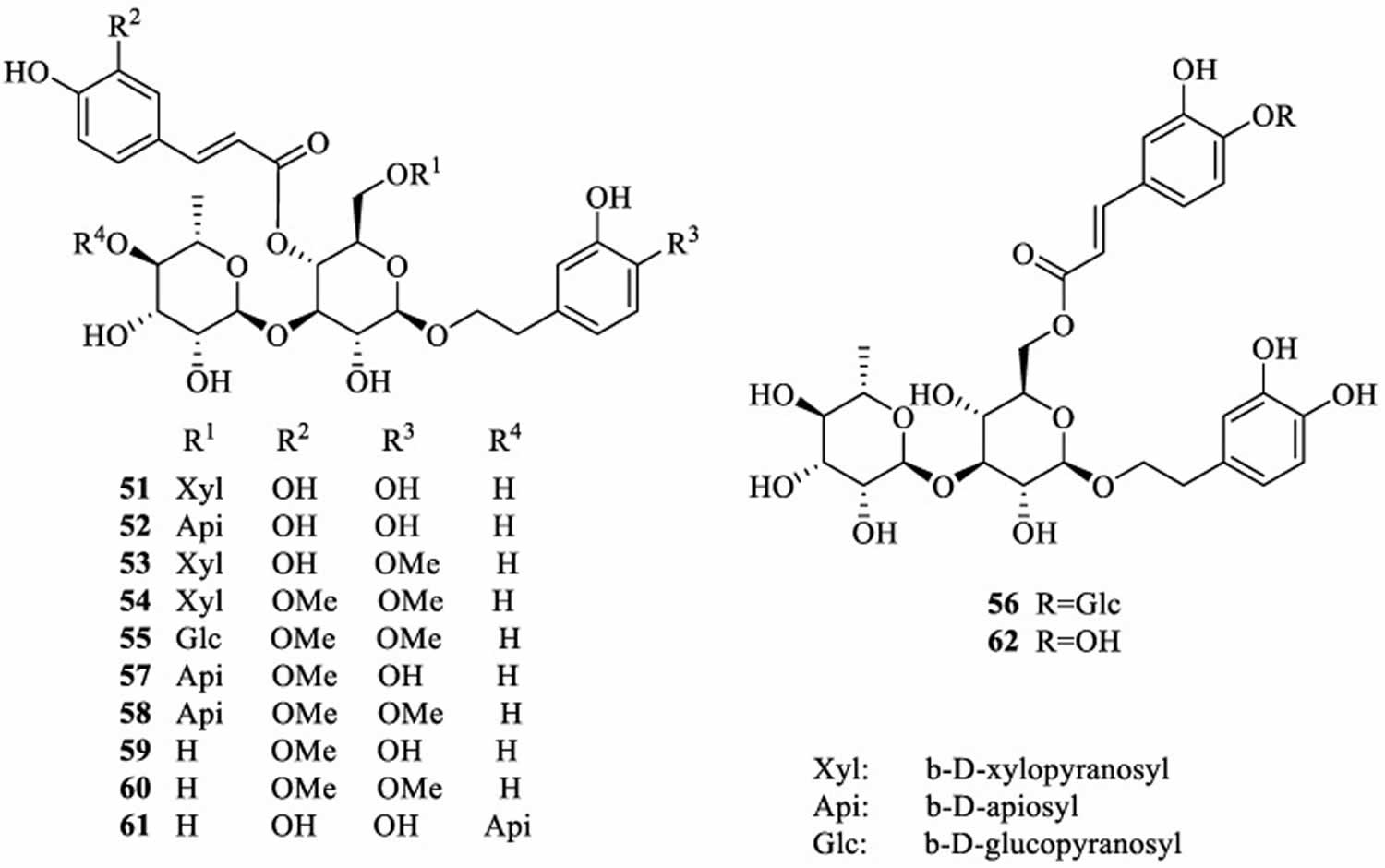

[Source 28 ]Figure 6. Phenylethanoid glycosides isolated from mullein

Footnotes: Phenylethanoid glycosides include compounds 51–56, alyssonoside (57), leucosceptoside B (58), verbacoside (3), leucosceptoside A (59), martynoside (60), samioside (61) and isoverbascoside (62).

[Source 28 ]Figure 7. Saponine 3-O-fucopyranosylsaikogenin F isolated from mullein

[Source 28 ]Table 1. Bioactive compounds isolated from common mullein (Verbascum thapsus) and other members of Verbascum species

| Compound(s) | Verbascum species | Isolated from | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triterpenoid saponins, iridoid glycosides, steroids, sesquiterpenes, sterones | Verbascum thapsus | Whole plant | 29 |

| Phenylethanoid glycosides, lignans, laterioside and harpagoside | Verbascum thapsus | Whole plant | 30 |

| Siakogenins, oligosaccharides, flavones | Verbascum thapsus | Whole plant | 31 |

| Ajugol, picroside IV, buddlindeterpene A, B and C | Verbascum thapsus | Whole plant | 32 |

| Flavonoids and phenylethanoids. | Verbascum densiflorum, Verbascum phlomoides | Flowers | 33 |

| Phenylethanoid glycosides | Verbascum wiedemannianum | Roots | 34 |

| Verbaspinoside, ajugol, phenylpropanoid glycosides | Verbascum spinosum | Aerial parts | 35 |

Types of mullein

The genus Verbascum (Scrophulariaceae, Lamiales) comprises more than 300 Eurasiatic species 6. It is the largest genus of the Scrophulariaceae family and its origin is the center of the Eastern Mediterranean Basin. In the Iberian Peninsula, it is represented by 26 species 36.

Phenology is the study of periodic events in biological life cycles and how these are influenced by seasonal and interannual variations in climate, as well as habitat factors. According to phenological studies, mullein flowers bloom from June to September and this is the time of harvest of this plant 37. A review of studies shows that the amount of chemical compounds such as phenol and flavonoids in mullein plant depends more on the type of plant organ, the type of species, and the place of plant growth and environmental factors than on the time of harvest 28.

Mullein medicinal uses

Although mullein has a long history as a herbal remedy for the treatment of many disorders 38, high-quality clinical researches have not been conducted so far, and there is no approved drug from this plant 39. The traditional uses of common mullein (Verbascum thapsus L.) have generally focused on effects aimed at wound healing 40, 41, 42, and treating Parkinson’s disease 43, diabetes 44, bronchitis 45, stomachache 46, snake bites 46, spasmodic cough 41, skin diseases 47, asthma 48 and joint pains 48. The mullein plant is also used as astringent (a chemical that shrinks or constricts body tissues that helps cleanse skin, tightens pores, and makes the skin less oily) 41, sedative remedy 49, antioxidant 50, antibacterial 51, antiviral 52, anthelmintic 53, antihepatitis 54, anti-trichomonas 55, 56 and anti-leishmanial effects 57.

Recently the European Medicines Agency (the European equivalent to the FDA) Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products concluded that, on the basis of their long-standing use, mullein flower medicines can be used for relief of sore throat associated with dry cough and common cold 58. Mullein flower medicines should only be used in adults and adolescents over the age of 12 years 58. If symptoms worsen or last longer than 1 week whilst taking mullein flower medicine, a doctor or a qualified healthcare practitioner should be consulted. Detailed instructions on how to take mullein flower medicines and who can use them can be found in the package leaflet that comes with the mullein flower medicine.

The European Medicines Agency Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products noted the lack of clinical studies with mullein flower medicines 58. The European Medicines Agency Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products conclusions on the use of mullein flower medicines for relief of sore throat are based on their ‘traditional use’ 58. This means that, although there is insufficient evidence from clinical trials, the effectiveness of these herbal medicines is plausible and there is evidence that they have been used safely in this way for at least 30 years (including at least 15 years within the EU) 58. Moreover, the intended use does not require medical supervision.

Anti-inflammatory activity

There are no clinical studies regarding the anti-inflammatory use of mullein.

Anti-inflammatory activity has been described for extracts of various Verbascum species. Activity in wound healing has also been evaluated, with ambiguous findings reported 59, 60.

Antibacterial and anthelmintic activity

There are no clinical studies regarding the antimicrobial use of mullein. A clinical trial investigated the use of naturopathic ear drops in otitis media in children; however, because the preparation contained mullein and 6 other constituents, conclusions about any single agent are not possible 9.

In vitro activity against some viruses (influenza, herpes simplex) and common human pathogens (Klebsiella pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Escherichia coli) has been described 61, 62. Antitubercular and antiprotozoal activity has also been evaluated 63, 64. Garlic and mullein ear drops have been used to treat ear infections in cats and dogs 65. Activity by the plant against certain insects has also been described 66, 67. Anthelmintic activity of mullein methanolic extract was demonstrated with similar time-to-death rates when compared with albendazole 63.

Anti-cancer activity

There are no clinical studies regarding the use of mullein in cancer. In vitro studies have been conducted to determine the cytotoxicity of various Verbascum extracts, with activity demonstrated against various cancer cell lines 68.

Other uses

Mullein demonstrated relaxant activity in vitro 63. Inhibition of cholinesterase has also been described 69, as well as antioxidant activity 70.

Mullein oil

Mullein oil is extracted from the flower or leaves of the plant. Mullein oil is used as a remedy for earaches, eczema, and some other skin conditions.

A clinical trial investigated the use of naturopathic ear drops (containing abstracts of the herbs: garlic [0.05%], common mullein [25%], common marigold [28%], St. John’s wort [30%], lavender [5%] and vitamin E [2%] in olive oil [10%]) in acute otitis media (acute middle ear infection) in children; the researchers found the herbal drops reduced ear pain 9. They also pointed out that they cost less than antibiotics and didn’t have any side effects. However, because the preparation contained mullein and 6 other constituents, conclusions about any single agent are not possible 9.

Mullein oil uses

The traditional uses of common mullein (Verbascum thapsus L.) have generally focused on effects aimed at wound healing 40, 41, 42. Recently the European Medicines Agency (the European equivalent to the FDA) Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products concluded that, on the basis of their long-standing use, mullein flower medicines can be used for relief of sore throat associated with dry cough and common cold 58. Mullein flower medicines should only be used in adults and adolescents over the age of 12 years 58. The European Medicines Agency Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products conclusions on the use of these mullein flower medicines for relief of sore throat are based on their ‘traditional use’. This means that, although there is insufficient evidence from clinical trials, the effectiveness of these herbal medicines is plausible and there is evidence that they have been used safely in this way for at least 30 years (including at least 15 years within the EU). Moreover, the intended use does not require medical supervision.

Mullein side effects

At the time of the European Medicines Agency Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products assessment, no side effects had been reported with the use of mullein flower medicines 58, 71. Information regarding mullein safety and efficacy in pregnancy and lactation is lacking. Occupational airborne dermatitis has been reported for both American and European mullein 72. One toxicity study suggests mullein extracts to be toxic in radish seed and brine shrimp at high concentrations (2,500 to 10,000 mg/L) 73.

References- Turker AU, Camper ND. Biological activity of common mullein, a medicinal plant. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002 Oct;82(2-3):117-25. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00186-1

- USDA-NRCS, 2014. The PLANTS Database. Baton Rouge, USA: National Plant Data Center. http://plants.usda.gov

- PIER, 2014. Pacific Islands Ecosystems at Risk. Honolulu, USA: HEAR, University of Hawaii. http://www.hear.org/pier/index.html

- Verbascum thapsus (common mullein). https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/56652

- ISSG, 2014. Global Invasive Species Database (GISD). Invasive Species Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd

- Blanco-Salas J, Hortigón-Vinagre MP, Morales-Jadán D, Ruiz-Téllez T. Searching for Scientific Explanations for the Uses of Spanish Folk Medicine: A Review on the Case of Mullein (Verbascum, Scrophulariaceae). Biology. 2021; 10(7):618. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10070618

- Turker AU, Gurel E. Common mullein (Verbascum thapsus L.): recent advances in research. Phytother Res. 2005 Sep;19(9):733-9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1653

- Bruton-Seal J, Seal M. Hedgerow Medicine. Ludlow, UK: Merlin Unwin Books; 2009.

- Sarrell EM, Cohen HA, Kahan E. Naturopathic treatment for ear pain in children. Pediatrics. 2003 May;111(5 Pt 1):e574-9. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.e574

- Johnson L. A manual of the medical botany of North America. New York, USA: W. Wood & Company; 1884.

- McCarthy, E., & O’Mahony, J. M. (2011). What’s in a Name? Can Mullein Weed Beat TB Where Modern Drugs Are Failing?. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2011, 239237. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/239237

- Khan SA, Dastagir G, Uza NU, Muhammad A, Ullah R. Micromorphology, pharmacognosy, and bio-elemental analysis of an important medicinal herb: Verbascum thapsus L. Microsc Res Tech. 2020 Jun;83(6):636-646. doi: 10.1002/jemt.23454

- Akdemir Z, Kahraman Ç, Tatlı II, Akkol EK, Süntar I, Keles H. Bioassay-guided isolation of anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and wound healer glycosides from the flowers of Verbascum mucronatum lam. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136(3):436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.059

- Prakash V, Rana S, Sagar A. Studies on antibacterial activity of Verbascum thapsus. J Med Plants Stud. 2016;4(3):101–103.

- Escobar FM, Sabini MC, Zanon SM, Cariddi LN, Tonn CE, Sabini LI. Genotoxic evaluation of a methanolic extract of Verbascum thapsus using micronucleus test in mouse bone marrow. Nat Prod Commun. 2011 Jul;6(7):989-91.

- Ali, N., Ali Shah, S. W., Shah, I., Ahmed, G., Ghias, M., Khan, I., & Ali, W. (2012). Anthelmintic and relaxant activities of Verbascum Thapsus Mullein. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 12, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-29

- Rezaie A, Ebrahimi M, Issabeagloo E, Kumar M, Nazeri M, Rezaie S, et al. Study of sedative, pre-anesthetic, and anti-anxiety effects of Verbascum thapsus L. extract compared with diazepam in rats. Adv Bio Res. 2012;3(4):84–89.

- Taleb, S., & Saeedi, M. (2021). The effect of the Verbascum Thapsus on episiotomy wound healing in nulliparous women: a randomized controlled trial. BMC complementary medicine and therapies, 21(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03339-6

- Murti K, Singh R, Paliwal D, Taya P, Divya S. Effect of Verbascum Thapsus L on normal and dexamethasone suppressed wound healing. Pharmacology. 2011;2:684–697.

- Demirci S, Doğan A, Demirci Y, Şahin F. In vitro wound healing activity of methanol extract of Verbascum speciosum. Int J Appl Res Nat Products. 2014;7(3):37–44.

- Speranza L, Franceschelli S, Pesce M, Reale M, Menghini L, Vinciguerra I, De Lutiis MA, Felaco M, Grilli A. Antiinflammatory effects in THP-1 cells treated with verbascoside. Phytother Res. 2010 Sep;24(9):1398-404. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3173

- Zhao YL, Wang SF, Li Y, He QX, Liu KC, Yang YP, Li XL. Isolation of chemical constituents from the aerial parts of Verbascum thapsus and their antiangiogenic and antiproliferative activities. Arch Pharm Res. 2011 May;34(5):703-7. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0501-9

- Akdemir Z, Kahraman C, Tatlı II, Küpeli Akkol E, Süntar I, Keles H. Bioassay-guided isolation of anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and wound healer glycosides from the flowers of Verbascum mucronatum Lam. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011 Jul 14;136(3):436-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.059

- Taleb S, Ozgoli G, Mojab F, Nsiri M, Ahvazi M. Effect of Verbascum Thapsus cream on intensity of episiotomy pain in primiparous women. Iranian J Obstetr Gynecol Infertility. 2016;19(7):9–17.

- Khuroo M.A., Qureshi M.A., Razdan T.K., Nichols P. Sterones, iridoids and a sesquiterpene from Verbascum thapsus. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:3541–3544. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(88)80764-7

- Sparg SG, Light ME, van Staden J. Biological activities and distribution of plant saponins. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004 Oct;94(2-3):219-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.05.016

- ElSohly HN, Danner S, Li XC, Nimrod AC, Clark AM. New antimycobacterial saponin from Colubrina retusa. J Nat Prod. 1999 Sep;62(9):1341-2. doi: 10.1021/np9901940

- M Amin, H. I., Hussain, F., Gilardoni, G., Thu, Z. M., Clericuzio, M., & Vidari, G. (2020). Phytochemistry of Verbascum Species Growing in Iraqi Kurdistan and Bioactive Iridoids from the Flowers of Verbascum calvum. Plants (Basel, Switzerland), 9(9), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9091066

- Khuroo MA, Qureshi MA, Razdan TK, Nichols P. Sterones, iridoids and a sesquiterpene from Verbascum thapsus . Phytochemistry. 1988;27(11):3541–3544.

- Warashina T, Miyase T, Ueno A. Phenylethanoid and lignan glycosides from Verbascum thapsus. Phytochemistry. 1992 Mar;31(3):961-5. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(92)80048-j

- Mehrotra R, Ahmed B, Vishwakarma RA, Thakur RS. Verbacoside: a new luteolin glycoside from Verbascum thapsus. Journal of Natural Products. 1989;52(3):640–643.

- Hussain H, Aziz S, Miana GA, Ahmad VU, Anwar S, Ahmed I. Minor chemical constituents of Verbascum thapsus . Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 2009;37(2):124–126.

- Klimek B, Olszewska MA, Tokar M. Simultaneous determination of flavonoids and phenylethanoids in the flowers of Verbascum densiflorum and V. phlomoides by high-performance liquid chromatography. Phytochem Anal. 2010 Mar-Apr;21(2):150-6. doi: 10.1002/pca.1171

- Abougazar H, Bedir E, Khan IA, Caliş I. Wiedemanniosides A-E: new phenylethanoid glycosides from the roots of Verbascum wiedemannianum. Planta Med. 2003 Sep;69(9):814-9. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43214

- Kalpoutzakis E, Aligiannis N, Mitakou S, Skaltsounis AL. Verbaspinoside, a new iridoid glycoside from Verbascum spinosum. J Nat Prod. 1999 Feb;62(2):342-4. doi: 10.1021/np980351f

- Benedí, C. Verbascum. Flora Iberica. In Flora Iberica; Benedí Gonzalez, C., Rico Hernández, E., Güemes Heras, J., Herrero Nieto, A., Eds.; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2009; Volume 13, pp. 49–97.

- Karimian V, Vahabi M, Fazilati M, Tarkesh EM. Classification the rangeland habitat of Verbascum songaricum schrenk using cluster analysis method. Desert Ecosyst Eng J. 2014;3(4):21–34.

- Verbascum thapsus (common mullein). https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/56652

- Mullein. https://www.drugs.com/npp/mullein.html

- Derakhshanfar, A., Moayedi, J., Derakhshanfar, G., & Poostforoosh Fard, A. (2019). The role of Iranian medicinal plants in experimental surgical skin wound healing: An integrative review. Iranian journal of basic medical sciences, 22(6), 590–600. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijbms.2019.32963.7873

- Ullah M, Khan MU, Mahmood A, Malik RN, Hussain M, Wazir SM, Daud M, Shinwari ZK. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Wana district south Waziristan agency, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013 Dec 12;150(3):918-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.032

- Benítez G, González-Tejero MR, Molero-Mesa J. Knowledge of ethnoveterinary medicine in the Province of Granada, Andalusia, Spain. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012 Jan 31;139(2):429-39. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.029

- de Rus Jacquet, A., Timmers, M., Ma, S. Y., Thieme, A., McCabe, G. P., Vest, J., Lila, M. A., & Rochet, J. C. (2017). Lumbee traditional medicine: Neuroprotective activities of medicinal plants used to treat Parkinson’s disease-related symptoms. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 206, 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.02.021

- McCune LM, Johns T. Antioxidant activity relates to plant part, life form and growing condition in some diabetes remedies. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007 Jul 25;112(3):461-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.006

- Miara M.D., Bendif H., Rebbas K., Rabah B., Hammou M.A., Maggi F. Medicinal plants and their traditional uses in the highland region of Bordj Bou Arreridj (Northeast Algeria) J. Herb. Med. 2019;16:100262. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2019.100262

- Shah A, Bharati KA, Ahmad J, Sharma MP. New ethnomedicinal claims from Gujjar and Bakerwals tribes of Rajouri and Poonch districts of Jammu and Kashmir, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015 May 26;166:119-28. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.01.056

- Sharma J, Gairola S, Sharma YP, Gaur RD. Ethnomedicinal plants used to treat skin diseases by Tharu community of district Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014 Dec 2;158 Pt A:140-206. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.004

- Murad W., Ahmad A., Gilani S.A., Khan M.A. Indigenous knowledge and folk use of medicinal plants by the tribal communities of Hazar Nao Forest, Malakand district, North Pakistan. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011;5:1072–1086.

- Verma J., Thakur K., Kusum Ethnobotanically important plants of Mandi and Solan districts of Himachal Pradesh, Northwest Himalaya. Plant Arch. 2012;12:185–190.

- Mihailović V., Kreft S., Benković E.T., Ivanović N., Stanković M.S. Chemical profile, antioxidant activity and stability in stimulated gastrointestinal tract model system of three Verbascum species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016;89:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.04.075

- Dulger G., Tutenocakli T., Dulger B. Anti-staphylococcal activity of Verbascum thapsus L. against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Konuralp Med. J. 2017;9:53–57.

- Escobar FM, Sabini MC, Zanon SM, Tonn CE, Sabini LI. Antiviral effect and mode of action of methanolic extract of Verbascum thapsus L. on pseudorabies virus (strain RC/79). Nat Prod Res. 2012;26(17):1621-5. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2011.576394

- Riaz M., Rahman N., Zia-Ul-Haq M. Anthelmintic and insecticidal activities of Verbascum thapsus L. Pak. J. Zool. 2013;45:1593–1598.

- Samani, Z.N.; Kopaei, M.R. Effective medicinal plants in treating hepatitis B. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2018, 9, 3589–3596.

- Kashan, Z.F.; Delavari, M.; Arbabi, M.; Hooshyar, H. Therapeutic effects of Iranian herbal extracts against Trichomonas vaginalis. Iran. Biomed. J. 2017, 21, 285–293

- Mehriardestani, M.; Aliahmadi, A.; Toliat, T.; Rahimi, R. Medicinal plants and their isolated compounds showing anti-Trichomonas vaginalis-activity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 88, 885–893.

- Kheiri Manjili H, Jafari H, Ramazani A, Davoudi N. Anti-leishmanial and toxicity activities of some selected Iranian medicinal plants. Parasitol Res. 2012 Nov;111(5):2115-21. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3059-7

- Verbasci flos. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/herbal/verbasci-flos

- Süntar I, Tatli II, Küpeli Akkol E, Keleş H, Kahraman Ç, Akdemir Z. An ethnopharmacological study on Verbascum species: from conventional wound healing use to scientific verification. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132(2):408-413.20709167

- Akdemir Z, Kahraman C, Tatli II, Küpeli Akkol E, Süntar I, Keles H. Bioassay-guided isolation of anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and wound healer glycosides from the flowers of Verbascum mucronatum Lam. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136(3):436-443.20621642

- Escobar FM, Sabini MC, Zanon SM, Tonn CE, Sabini LI. Antiviral effect and mode of action of methanolic extract of Verbascum thapsus L. on pseudorabies virus (strain RC/79). Nat Prod Res. 2012;26(17):1621-1625.21999656

- Mothana RA, Abdo SA, Hasson S, Althawab FM, Alaghbari SA, Lindequist U. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities and phytochemical screening of some yemeni medicinal plants. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2010;7(3):323-330.18955315

- Ali N, Ali Shah SW, Shah I, et al. Anthelmintic and relaxant activities of Verbascum Thapsus Mullein [published online March 30, 2012]. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:29.2246373010.1186/1472-6882-12-29

- Mothana RA, Al-Musayeib NM, Al-Ajmi MF, Cos P, Maes L. Evaluation of the in vitro antiplasmodial, antileishmanial, and antitrypanosomal activity of medicinal plants used in Saudi and Yemeni traditional medicine [published online May 21, 2014]. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:905639.2496333010.1155/2014/905639

- Lans C, Turner N, Khan T. Medicinal plant treatments for fleas and ear problems of cats and dogs in British Columbia, Canada. Parasitol Res. 2008;103(4):889-898.18563443

- Alba C, Bowers MD, Blumenthal D, Hufbauer RA. Chemical and mechanical defenses vary among maternal lines and leaf ages in Verbascum thapsus L. (Scrophulariaceae) and reduce palatability to a generalist insect. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e104889.25127229

- Hammad EA, Zeaiter A, Saliba N, Talhouk S. Bioactivity of indigenous medicinal plants against the cotton whitefly, Bemisia tabaci [published online August 1, 2014]. J Insect Sci. 2014;14:105.2520475610.1673/031.014.105

- Talib WH, Mahasneh AM. Antiproliferative activity of plant extracts used against cancer in traditional medicine. Sci Pharm. 2010;78(1):33-45.21179373

- Georgiev M, Alipieva K, Orhan I, Abrashev R, Denev P, Angelova M. Antioxidant and cholinesterases inhibitory activities of Verbascum xanthophoeniceum Griseb. and its phenylethanoid glycosides. Food Chem. 2011;128(1):100-105.25214335

- Moein S, Moein M, Khoshnoud MJ, Kalanteri T. In vitro antioxidant properties evaluation of 10 Iranian medicinal plants by different methods. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14(12):771-775.23482923

- Burdock GA, 2009. Fenaroli’s Handbook of Flavor Ingredients. 6th Edition. CRC press. Taylor & Francis Group. Boca Raton, FL, 1443 pp. 10.1201/9781439847503

- Castro AI, Carmona JB, Gonzales FG, Nestar OB. Occupational airborne dermatitis from gordolobo (Verbascum densiflorum). Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55(5):301.17026698

- Turker AU, Camper ND. Biological activity of common mullein, a medicinal plant. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82(2-3):117-125.12241986