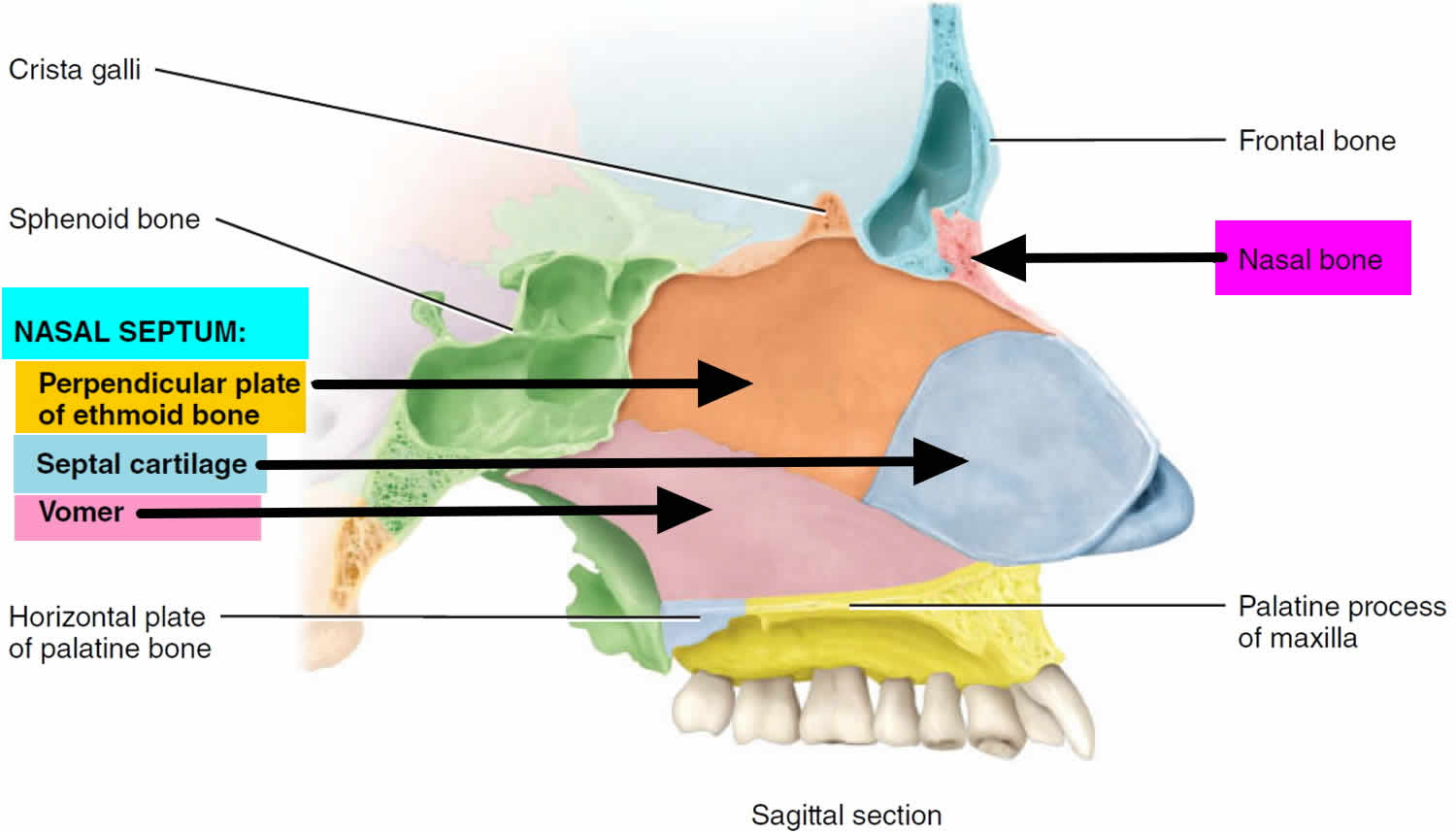

What is nasal septum

Nasal septum is in the midline of the nose and made of flat cartilage anteriorly and bone posteriorly. Nasal septum is a vertical partition that divides the nasal cavity into right and left sides. The perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone forms the superior part of the nasal septum. Whilst the vomer, maxillary and palatine bones form the inferior part of the nasal septum 1. The anterior portion of the nasal septum is made of irregular quadrangular hyaline cartilage that inserts into the nasomaxillary crest of the maxilla and nasal spine 2.

The nasal septum bone and cartilage are covered by a special skin called a mucous membrane that has many blood vessels in it. Ideally, the left and right nasal passageways are equal in size. However, it is estimated that as many as 80 percent of people have a nasal septum that is off-center. This is called a deviated nasal septum, which may or may not cause certain symptoms.

Figure 1. Nasal septum

Nasal septum function

Nasal septum function

The 3 primary functions of the nose are to aid in respiration, to filter and defend against external particles and allergens, and to enable olfaction. The nasal cycle is a physiologic alternation of resistance between the two nasal airways, created by changes in congestion and decongestion and has been suggested to aid in respiratory defense 3.

Epithelial Cells (Cilia)

Epithelial cells provide a physical barrier that prevents invasion of underlying tissue. Stratified squamous epithelium within the cavity gives way to pseudostratified columnar respiratory epithelium further along in the respiratory tract. Cilia at the apex of epithelial cells act to propel mucus, allergens, and foreign particles from the nasal cavity towards the pharynx where they are removed by swallowing. Epithelial cells are also involved in the inflammatory response by releasing cytokines.

Endothelial Cells (Underlying Blood Vessels)

The rich blood supply to the nasal mucosa is formed by endothelial cells. This thin layer of cells allows rapid warming of air entering the respiratory passage. Smooth muscle surrounding this endothelial layer allows constriction and dilation of blood vessels, functioning to regulate congestion of the nasal passage during an inflammatory response.

Mucus Glands

Mucus produced in the lamina propria is released via glands onto the epithelial surface. The mucus functions to trap external particles while also preserving the epithelial barrier. An increase in parasympathetic stimulation leads to an increase in mucus production and release. Lysozymes and IgA are found within the mucus and protect from invading microbes 4.

Neurons

Receptor neurons in the roof of the nasal cavity recognize and bind odor molecules. These stimuli lead to depolarization of the neurons and ultimately signal propagation along the olfactory nerves toward the central nervous system (CNS).

Respiration

As air is inhaled, the nasal cavity assists in respiration by preparing air for oxygen exchange. Due to the narrow nature of the cavity, inhaled air is rapidly introduced to a large mucosal surface area with a rich supply of blood at body temperature. This facilitates rapid acclimation of inhaled air to a temperature better suited for the lungs 5. Humidification functions to protect the fragile respiratory and olfactory epithelia 6.

Defense

The nasal cavity also aids in the defense of respiratory tissues. Mucus secretions trap particles and antigens carried into the respiratory system during inhalation. As pathogens are trapped in these secretions, they are bound by secretory IgA dimers (a component of the adaptive immune response), which prevents attachment of pathogens to host epithelium, thus hindering invasion. Mucus can also contain IgE, which is involved in the allergic response and can cause a pathologic type 1 hypersensitivity reaction 7. Cilia within the nasal cavity also function to propel mucus away from the lungs in an attempt to expel trapped pathogens from the body 8. The bacterial normal flora in the nasal mucosa also protects from invasion by competing with invading bacteria for space and nutrients 9.

Olfaction

In addition, the nasal cavity enables olfaction. Olfaction helps to identify sources of nearby danger or nutrition, as well as influencing mood and sexuality 10. As air enters the nasal cavity, the turbinates function to direct a portion of the airflow to the higher regions of the cavity. The olfactory cleft is located at the roof of the nasal cavity in near proximity to the cribriform plate. Olfactory receptors located here bind to odorants carried into the nose during inhalation and send signals to the olfactory cortex and other brain regions 11.

Nasal septum deviation

A deviated septum occurs when the thin wall (nasal septum) between your nasal passages is displaced to one side. In many people, the nasal septum is displaced — or deviated — making one nasal passage smaller.

When a deviated nasal septum is severe, it can block one side of your nose and reduce airflow, causing difficulty breathing. The additional exposure of a deviated septum to the drying effect of airflow through the nose may sometimes contribute to crusting or bleeding in certain individuals.

Nasal obstruction can occur from a deviated nasal septum, from swelling of the tissues lining the nose, or from both. Treatment of nasal obstruction may include medications to reduce the swelling or nasal dilators that help open the nasal passages. To correct a deviated septum, surgery is necessary.

See your doctor if you experience:

- A blocked nostril (or nostrils) that doesn’t respond to treatment

- Frequent nosebleeds

- Recurring sinus infections

Figure 2. Deviated nasal septum

Nasal septum deviation causes

A deviated septum occurs when your nasal septum — the thin wall that separates your right and left nasal passages — is displaced to one side.

A deviated septum can be caused by:

- A condition present at birth. In some cases, a deviated septum occurs during fetal development and is apparent at birth.

- Injury to the nose. A deviated septum can also be the result of an injury that causes the nasal septum to be moved out of position. In infants, such an injury may occur during childbirth. In children and adults, a wide array of accidents may lead to a nose injury and deviated septum — from tripping on a step to colliding with another person on the sidewalk. Trauma to the nose most commonly occurs during contact sports, active play or roughhousing, or automobile accidents.

The normal aging process may affect nasal structures, worsening a deviated septum over time. Also, changes in the amount of swelling of nasal tissues, because of developing rhinitis or rhinosinusitis, can accentuate the narrowing of a nasal passage from a deviated septum, resulting in nasal obstruction.

Risk factors for deviated septum

For some people, a deviated septum is present at birth — occurring during fetal development or due to injury during childbirth. After birth, a deviated septum is most commonly caused by an injury that moves your nasal septum out of place. Risk factors include:

- Playing contact sports

- Not wearing your seat belt while riding in a motorized vehicle

Nasal septum deviation prevention

You may be able to prevent the injuries to your nose that can cause a deviated septum with these precautions:

- Wear a helmet or a midface mask when playing contact sports, such as football and volleyball.

- Wear a seat belt when riding in a motorized vehicle.

Nasal septum deviation symptoms

Most nasal septum deformities result in no symptoms, and you may not even know you have a deviated septum. The most common symptom from a badly deviated or crooked nasal septum is difficulty breathing through the nose, which is usually worse on one side. In some cases, a crooked septum can interfere with sinus drainage and cause repeated sinus infections. You may experience one or more of the following:

- Obstruction of one or both nostrils. This obstruction can make it difficult to breathe through one or both nostrils. This may be more noticeable when you have a cold (upper respiratory tract infection) or allergies that can cause your nasal passages to swell and narrow.

- Nosebleeds. The surface of your nasal septum may become dry, increasing your risk of nosebleeds.

- Facial pain. Though there is some debate about the possible nasal causes of facial pain, a severe deviated septum that impacts the inside nasal wall, when on the same side as one-sided facial pain, is sometimes considered a possible cause.

- Sinus infections

- Noisy breathing during sleep. This can occur in infants and young children with a deviated septum or with swelling of the intranasal tissues.

- Mouth-breathing during sleep in adults

- Awareness of the nasal cycle. It is normal for the nose to alternate being obstructed on one side, then changing to being obstructed on the other. This is called the nasal cycle. The nasal cycle is a normal phenomenon, but being aware of the nasal cycle is unusual and can be an indication that there is an abnormal amount of nasal obstruction.

- Preference for sleeping on a particular side. Some people may prefer to sleep on a particular side in order to optimize breathing through the nose at night. This can be due to a deviated septum that narrows one nasal passage.

Nasal septum deviation complications

If you have a severely deviated septum causing nasal obstruction, it can lead to:

- Dry mouth, due to chronic mouth breathing

- A feeling of pressure or congestion in your nasal passages

- Disturbed sleep, due to the unpleasantness of not being able to breathe comfortably through the nose at night

- Inferior turbinate hypertrophy—turbinates are finger-like structures in your nose that warm and moisten the air you breathe, and sometimes the lower ones can get too big

- Concha bullosa of the middle turbinate—this is when one of the turbinates next to your sinus openings gets a big air bubble in it

- Nasal valve collapse (internal or external)

- Sinusitis (acute, recurrent, chronic)

- Headaches (contact point)

- External nasal deformity (change in the shape of the nose)

- Decreased sense of smell

Nasal septum deviation diagnosis

During your visit, your doctor will first ask about any symptoms you may have.

To examine the inside of your nose, the doctor will use a bright light and sometimes an instrument (nasal speculum) designed to spread open your nostrils. Sometimes the doctor will check farther back in your nose with a long tube-shaped scope with a bright light at the tip. The doctor may also look at your nasal tissues before and after applying a decongestant spray.

Based on this exam, he or she can diagnose a deviated septum and determine the seriousness of your condition.

If your doctor is not an otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat specialist) and treatment is deemed necessary, you may be referred to a specialist for further consultation and treatment.

Nasal septum deviation treatment

Managing symptoms

Initial treatment of a deviated septum may be directed at managing the symptoms of the tissues lining the nose, which may then contribute to symptoms of nasal obstruction and drainage. Your doctor may prescribe:

- Decongestants. Decongestants are medications that reduce nasal tissue swelling, helping to keep the airways on both sides of your nose open. Decongestants are available as a pill or as a nasal spray. Use nasal sprays with caution, however. Frequent and continued use can create dependency and cause symptoms to be worse (rebound) after you stop using them. Decongestants have a stimulant effect and may cause you to be jittery as well as elevate your blood pressure and heart rate.

- Antihistamines. Antihistamines are medications that help prevent allergy symptoms, including obstruction and runny nose. They can also sometimes help nonallergic conditions such as those occurring with a cold. Some antihistamines cause drowsiness and can affect your ability to perform tasks that require physical coordination, such as driving.

- Nasal steroid sprays. Prescription nasal corticosteroid sprays can reduce inflammation in your nasal passage and help with obstruction or drainage. It usually takes from one to three weeks for steroid sprays to reach their maximal effect, so it is important to follow your doctor’s directions in using them.

Medications only treat the swollen mucus membranes and won’t correct a deviated septum.

Nasal septum deviation septoplasty

If you still experience symptoms despite medical therapy, you may consider deviated nasal septum surgery to correct your deviated septum (septoplasty).

Septoplasty is the preferred surgical treatment to correct a deviated septum. Septoplasty procedure is typically not performed on young children, unless the problem is severe, because facial growth and development are still occurring. Septoplasty is a surgical procedure that is usually performed through the nostrils, so there is no bruising or outward sign of surgery; however, each case is different and special techniques may be required depending on the individual patient.

During septoplasty, your nasal septum is straightened and repositioned in the center of your nose.

The time required for the septoplasty operation averages about one- to one-and-a-half hours, depending on the type of deformity. It can be done with a local or a general anesthetic, usually on an outpatient basis. During the surgery, badly deviated portions of the nasal septum may be removed entirely, or they may be readjusted and reinserted into the nose in the proper position. Surgery may be combined with a rhinoplasty that changes the outward shape of the nose; in this case swelling and bruising may occur. Septoplasty may also be combined with sinus surgery.

The level of improvement you can expect with surgery depends on the severity of your deviation. Symptoms due to the deviated septum — particularly nasal obstruction — often completely resolve. However, any accompanying nasal or sinus conditions affecting the tissues lining your nose — such as allergies — can’t be cured with only surgery.

Potential complications from septoplasty (surgery) can include:

- Anesthesia complications

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Creation of a hole connecting the right and left sides of the nasal cavity (called a septal perforation)

- Numbness of the upper teeth and nose

- Cerebrospinal fluid leak (extremely rare)

- Change in the external shape of the nose

Reshaping your nose

In some cases, surgery to reshape the nose (rhinoplasty) is performed at the same time as septoplasty. Rhinoplasty involves modifying the bone and cartilage of your nose to change its shape or size or both.

Nasal septum perforation

Hole in nasal septum or nasal septum perforation is a full-thickness defect of the nasal septum. Nasal septum perforation occurs most commonly along the anterior cartilaginous septum 12. Nasal septum perforation symptoms can include nasal obstruction, whistling, nosebleed (epistaxis), crusting, pain, runny nose (rhinorrhea), chronic rhinosinusitis, or foul smell.

Overuse of vasoconstrictive nasal spray can erode nasal mucosa and predispose to septal perforation. For users of nasal steroid spray, the nozzle should be directed laterally to avoid showering the septum with local steroid which can cause thinning of the septal mucosa.

Workup of septal perforation is dictated based on the clinical scenario. For example, in patients with an antecedent history of septoplasty after which perforation was noted, biopsy and laboratory workup is usually not indicated.

Medical management of septal perforation includes avoidance of manipulation and diligent humidification.

After septal perforation repair, care should be taken to avoid nose blowing for approximately one month after repair.

Nasal septum perforation causes

Nasal septum perforation causes include trauma, autoimmune (such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis), infectious (syphilis, fungal disease, tuberculosis), or neoplastic. Immunocompromised individuals may be at higher risk for opportunistic infections such as fungal infections. Iatrogenic septal perforation can occur after patient self-manipulation, after cautery for epistaxis, or after elective septoplasty. The reported incidence of septal perforation after septoplasty ranges from 0.5% to 3.1% 13. Other causes can include intranasal drug abuse, steroid nasal spray, or vasoconstrictor nasal spray.

Certain occupations are at higher risk. Historically, chrome platers suffered inflammation, erosion, and perforation after exposure to the offending chromic mist 12. Today, woodworkers and metal workers exposed to nickel dust are at higher risk of intranasal carcinoma.

The blood supply to the nasal septum arises from branches of the maxillary artery (sphenopalatine artery and greater palatine artery, superior labial artery (a branch of the facial artery), and the ophthalmic artery (anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries). The majority of the blood supply arises from branches of the maxillary artery which together supply the mucoperichondrial leaflets that cover each side of the septal cartilage. Any threat to the vascularity of these leaflets can jeopardize the viability of the underlying cartilage, predisposing to septal perforation. Septal perforations alter nasal airflow, creating turbulence which causes mucosal dryness which can predispose to crusting and epistaxis. Disturbance in laminar airflow can also cause subjective nasal obstruction or audible whistling noticeable during rest, sleep, or exercise.

Figure 3. Nasal septum perforation

Hole in nasal septum symptoms

Nasal septum perforation symptoms can include nasal obstruction, whistling, nosebleed (epistaxis), crusting, pain, runny nose (rhinorrhea), chronic rhinosinusitis, or foul smell.

Nasal septum perforation diagnosis

A careful history will often provide information regarding cause of hole in nasal septum; this should include details regarding past nasal trauma, intranasal drug use (prescription, OTC, and illicit), nasal hygiene, pulmonary symptoms, renal symptoms, and autoimmune disease. Data collection should include details regarding the onset, duration, timing, and severity of symptoms, as well as delineation of prior therapies.

The physical exam should ascertain dimensions of the septal perforation in both horizontal and vertical dimensions, which can is doable in the clinic by using a headlight, a nasal speculum, and a pre-marked cotton-tipped applicator. The determination should be made of the relative vertical height of the septum as this can be a proxy for mucoperichondrium available for superiorly-based or bipedicled intranasal tissue rearrangement in the context of repair. Saddle deformity of the nasal dorsum should be noted as large perforations can threaten dorsal nasal support. Inflammatory conditions may cause granulation tissue or excessive crusting. Inspection for foreign material may give clues regarding illicit drug use. An intraoral exam can rule out palatal involvement. Inspection of the ear or temporal region (cartilage, temporalis fascia) can provide information regarding donor sites if repair becomes necessary.

When the cause of nasal septum perforation is less clear, biopsy of the perforation is performed and sent to pathology for permanent section. The patient should receive counsel that the biopsy will by definition cause enlargement of the perforation. The posterior edge is the area generally biopsied as horizontal enlargement usually does not adversely affect repair options 14. Blood work includes ANCA, ANA, RF, ESR, CRP, FTA-ABS, ACE. Imaging may be indicated and can include CXR or CT scan of the sinuses. If tuberculosis is suspected, PPD or other tuberculosis testing may be warranted.

Nasal septum perforation treatment

Treatment of hole in nasal septum can include medical and surgical management. Medical management includes providing humidification and emollients inside the nose to minimize discomfort, crusting, and epistaxis. Caution is advisable when using petroleum-containing products inside the nose to minimize aspiration and subsequent lipoid pneumonia. Saline and water-based gels are typically safer.

For patients who may be poor candidates for general anesthesia or formal repair, nasal septal prostheses are available. These mechanically cover the perforation and are generally fabricated of medical-grade synthetic material. Tolerance to the prosthesis is variable, and ongoing humidification is helpful. Prostheses have an overall low infection rate 15.

Many types of surgical repair for nasal septal perforation have been described. These include the classic bilateral mucoperichondrial flap repair with an interpositional graft 16, staged inferior turbinate flap 17, acellular dermis graft 18, auricular cartilage interposition 19, facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap 20. Not surprisingly, large septal perforations >20mm have a higher failure rate after the repair than smaller ones. Poor candidates for repair or patients with large perforations may benefit from posterior septal resection, essentially removing the posterior wall of the perforation with an attempt to mitigate symptoms 21.

If autoimmune disease is present, caution is warranted. A recent systematic review of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis) and septal perforation recommended against septal perforation repair in this group, even in the setting of quiescent disease 22.

References- Schlosser RJ, Park SS. Functional nasal surgery. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 1999 Feb;32(1):37-51

- Galarza-Paez L, Downs BW. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Nose. [Updated 2018 Nov 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532870

- Eccles R. A role for the nasal cycle in respiratory defence. Eur. Respir. J. 1996 Feb;9(2):371-6.

- Masuda N, Mantani Y, Yoshitomi C, Yuasa H, Nishida M, Arai M, Kawano J, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N, Kitagawa H. Immunohistochemical study on the secretory host defense system with lysozyme and secretory phospholipase A2 throughout rat respiratory tract. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2018 Mar 02;80(2):323-332

- Rouadi P, Baroody FM, Abbott D, Naureckas E, Solway J, Naclerio RM. A technique to measure the ability of the human nose to warm and humidify air. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999 Jul;87(1):400-6

- Mercke U, Hakansson CH, Toremalm NG. The influence of temperature on mucociliary activity. Temperature range 20 degrees C-40 degrees C. Acta Otolaryngol. 1974 Nov-Dec;78(5-6):444-50

- Olivé Pérez A, Cisteró Bahima A. [IgE values in nasal mucus in the diagnosis of perennial allergic rhinitis]. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 1981 Mar-Apr;9(2):131-6

- Munkholm M, Mortensen J. Mucociliary clearance: pathophysiological aspects. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2014 May;34(3):171-7

- Shinefield HR, Wilsey JD, Ribble JC, Boris M, Eichenwald HF, Dittmar CI. Interactions of staphylococcal colonization. Influence of normal nasal flora and antimicrobials on inoculated Staphylococcus aureus strain 502A. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1966 Jan;111(1):11-21

- Patel RM, Pinto JM. Olfaction: anatomy, physiology, and disease. Clin Anat. 2014 Jan;27(1):54-60

- Pinto JM. Olfaction. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011 Mar;8(1):46-52

- Downs BW, Sauder HM. Septal Perforation. [Updated 2019 Mar 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537208

- Quinn JG, Bonaparte JP, Kilty SJ. Postoperative management in the prevention of complications after septoplasty: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2013 Jun;123(6):1328-33

- Watson D, Barkdull G. Surgical management of the septal perforation. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 2009 Jun;42(3):483-93

- Taylor RJ, Sherris DA. Prosthetics for nasal perforations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015 May;152(5):803-10

- Pedroza F, Patrocinio LG, Arevalo O. A review of 25-year experience of nasal septal perforation repair. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007 Jan-Feb;9(1):12-8

- Xu M, He Y, Bai X. Effect of Temporal Fascia and Pedicle Inferior Turbinate Mucosal Flap on Repair of Large Nasal Septal Perforation via Endoscopic Surgery. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2016;78(6):303-307

- Kridel RWH, Delaney SW. Discussion: Acellular Human Dermal Allograft as a Graft for Nasal Septal Perforation Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018 Jun;141(6):1525-1527

- Ozturan O, Yenigun A, Senturk E, Eren SB, Aksoy F. Endoscopic Endonasal Repair of Septal Perforation with Interpositional Auricular Cartilage Grafting via a Mucosal Regeneration Technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Oct;155(4):714-7

- Heller JB, Gabbay JS, Trussler A, Heller MM, Bradley JP. Repair of large nasal septal perforations using facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2005 Nov;55(5):456-9

- Beckmann N, Ponnappan A, Campana J, Ramakrishnan VR. Posterior septal resection: a simple surgical option for management of nasal septal perforation. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Feb;140(2):150-4

- Coordes A, Loose SM, Hofmann VM, Hamilton GS, Riedel F, Menger DJ, Albers AE. Saddle nose deformity and septal perforation in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018 Feb;43(1):291-299