What is neurocysticercosis

Neurocysticercosis is a parasitic tissue infection caused by larval cysts of the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium, in the brain and are a major cause of adult onset seizures in most low-income countries 1. The prevalence of neurocysticercosis in some of these developing countries exceeds 10% 2, where it accounts for up to 50% of cases of late-onset epilepsy 3. The larval cysts of the tapeworm Taenia solium also infect muscle or other tissue. A person gets cysticercosis by swallowing eggs found in the feces of a person who has an intestinal tapeworm Taenia solium. People living in the same household with someone who has a tapeworm have a much higher risk of getting cysticercosis than people who don’t. People do not get cysticercosis by eating undercooked pork. Eating undercooked pork can result in intestinal tapeworm if the pork contains larval cysts. Pigs become infected by eating tapeworm eggs in the feces of a human infected with a tapeworm.

Both the tapeworm infection, also known as taeniasis, and cysticercosis occur globally. The highest rates of infection are found in areas of Latin America, Asia, and Africa that have poor sanitation and free-ranging pigs that have access to human feces. Although uncommon, cysticercosis can occur in people who have never traveled outside of the United States. For example, a person infected with a tapeworm who does not wash his or her hands might accidentally contaminate food with tapeworm eggs while preparing it for others.

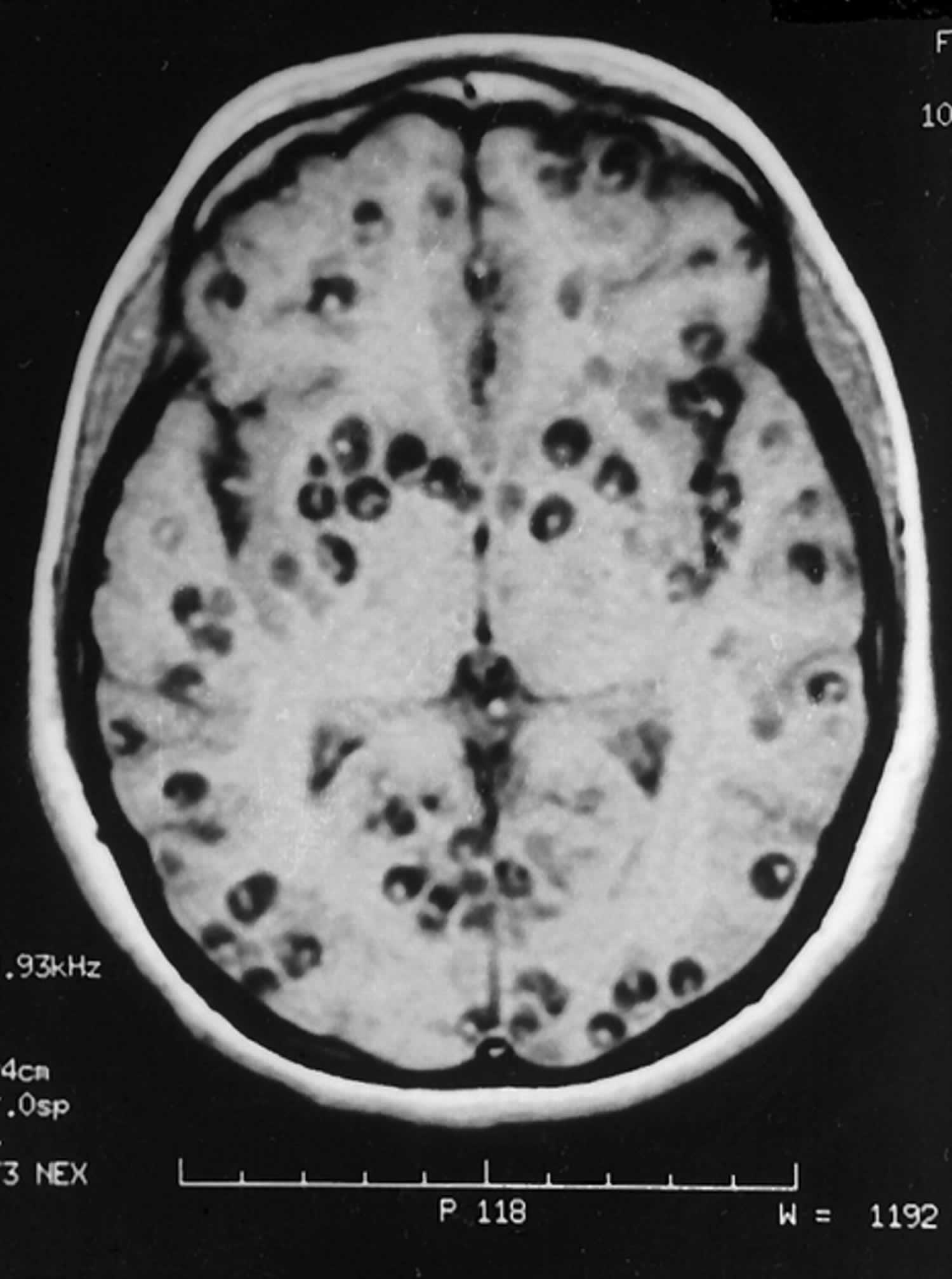

Neurocysticercosis can be both intra- and extra-axial. Commonest locations are 4:

- Subarachnoid space over the cerebral hemispheres: can be very large

- Parenchyma: most common location, frequently seen near the grey matter-white matter junction 5

- Basal cisterns:

- maybe “grape-like” (racemose), most lack an identifiable scolex

- Ventricles

- usually solitary cyst

- 4th ventricle: most frequent location

- Spinal forms: associated with concomitant intracranial involvement 5

Typically the parenchymal cysts are small (1 cm) whereas the subarachnoid cysts can be much bigger (up to 9 cm): differential, therefore, being an arachnoid cyst.

The treatment options available to patients with neurocysticercosis include symptomatic therapy (e.g. anti-epileptics) and anthelmintic therapy (e.g. albendazole and praziquantel, the two antiparasitics most commonly used), usually accompanied by corticosteroids. Surgery (e.g. VP shunt placement or decompression) is only rarely indicated.

Neurocysticercosis stages

There are four main neurocysticercosis stages (also known as Escobar’s pathological stages):

- Vesicular: Viable parasite with intact membrane and therefore no host reaction.

- cyst with dot sign

- CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) density/intensity

- hyperintense scolex on T1 can sometimes be seen

- no enhancement is typical, although very faint enhancement of the wall and enhancement of the scolex may be seen

- Colloidal vesicular: Parasite dies within 4-5 years 1 untreated, or earlier with treatment and the cyst fluid becomes turbid. As the membrane becomes leaky edema surrounds the cyst. This is the most symptomatic stage.

- cyst fluid becomes turbid

- CT: hyperattenuating to CSF

- MRI T1: hyperintense to CSF 6

- surrounding edema

- cyst and the wall become thickened and brightly enhances

- scolex can often still be seen as an eccentric focus of enhancement

- cyst fluid becomes turbid

- Granular nodular: Edema decreases as the cyst retract further; enhancement persists.

- edema decreases

- cyst retracts

- enhancement persists but is less marked 7

- Nodular calcified: End-stage quiescent calcified cyst remnant; no edema.

- end-stage quiescent calcified cyst remnant

- no edema

- no enhancement on CT

- signal drop out on T2 and T2* sequences

- some intrinsic high T1 signal may be present

- long term enhancement may be evident on MRI and may predict ongoing seizures 7

Neurocysticercosis causes

Neurocysticercosis is the result of accidental ingestion of eggs of Taenia solium (pork tapeworm), usually due to contamination of food by people with taeniasis. In developing countries, neurocysticercosis is the most common parasitic disease of the nervous system and is the main cause of acquired epilepsy. In the United States, neurocysticercosis is mainly a disease of immigrants.

Neurocysticercosis symptoms

Clinical manifestations of neurocysticercosis vary with the locations of the lesions, the number of parasites, and the host’s immune response 8. Many patients are asymptomatic. Seizures are the most frequent and often the only, clinical manifestation of neurocysticercosis; they occur in 70% to 90% of cases 9. Epilepsy is the most common presentation of neurocysticercosis and is also a complication of the disease 10. Neurocysticercosis is the leading cause of adult-onset epilepsy and is probably one of the most frequent causes of childhood epilepsy in the world. Seizures secondary to neurocysticercosis may be generalized or partial. Simple and complex partial seizures may be associated with the presence of a single lesion. Generalized seizures are usually tonic-clonic; this is thought to be related to the presence of multiple lesions. However, irritation of focal cortical tissue by one of the lesions most probably leads to focal onset with secondary generalization. Myoclonic seizures also have been described.

Possible neurocysticercosis symptomatic presentations include the following:

- Epilepsy: Most common presentation (70%)

- Headache, dizziness

- Stroke

- Neuropsychiatric dysfunction

- Hydrocephalus

- Altered mental status

- Neurological deficits

- Bruns syndrome: caused by cysticerci cysts of the third and fourth ventricle 5

Onset of most symptoms is usually subacute to chronic, but seizures present acutely.

Abnormal physical findings, which occur in 20% or less of patients with neurocysticercosis, depend on where the cyst is located in the nervous system and include the following:

- Cognitive decline

- Dysarthria

- Extraocular movement palsy or paresis

- Hemiparesis or hemiplegia, which may be related to stroke, or Todd paralysis

- Hemisensory loss

- Movement disorders

- Hyper/hyporeflexia

- Gait disturbances

- Meningeal signs

Headache

Headaches may be associated with intracranial hypertension and are indicative of hydrocephalus; they may also result from meningitis. Chronic headaches may be associated with nausea and vomiting (simulating migraines).

Intracranial hypertension

Most often, intracranial hypertension is due to obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation caused by basal or ventricular cysticercosis. It may also result from large cysts displacing midline structures, granular ependymitis, arachnoiditis, or the so-called cysticercotic encephalitis caused by the inflammatory response to a massive infestation of cerebral parenchyma with cysticerci. Affected patients may have seizures and deterioration of their mental status, mainly due to the host’s inflammatory reaction as an exaggerated response to the massive infestation.

Diplopia may also result from intracranial hypertension or arachnoiditis producing entrapment or compression of cranial nerves 3, 4 or 6.

Strokes

Ischemic cerebrovascular complications of neurocysticercosis include lacunar infarcts 11 and large cerebral infarcts due to occlusion or vascular damage. Hemorrhage can also occur and has been reported as a result of rupture of mycotic aneurysms of the basilar artery. Strokes may be responsible for paresis or plegias, involuntary movements, gait disturbances, or paresthesias 12.

Neuropsychiatric disturbances

Neuropsychiatric dysfunction can range from poor performance on neuropsychologic tests to severe dementia. These symptoms appear to be related more to the presence of intracranial hypertension than to the number or location of parasites in the brain.

Hydrocephalus

Ten to thirty percent of patients with neurocysticercosis develop communicating hydrocephalus due to inflammation and fibrosis of the arachnoid villi or inflammatory reaction to the meninges and subsequent occlusion of the foramina of Luschka and Magendie. Noncommunicating hydrocephalus may be a consequence of intraventricular cysts.

Presentations of other forms of neurocysticercosis

Patients with intrasellar neurocysticercosis present with ophthalmologic and endocrinologic manifestations mimicking those of pituitary tumors.

Spinal neurocysticercosis is rare and may be either intramedullary or extramedullary. The extramedullary form is the most frequent and is responsible of symptoms of spinal dysfunction such as radicular pain, weakness, and paresthesias. Intramedullary presentation may cause paraparesis, sensory deficits with a level, and sphincter disturbances.

Ocular cysticercosis occurs most commonly in the subretinal space. Patients may present with ocular pain, decreased visual acuity, visual field defects, or monocular blindness.

Systemic cysticercosis is most common in the Asian continent. The parasites may be located in the subcutaneous tissue or muscle. Peripheral nerve involvement as well as involvement of the liver or spleen have been reported.

Neurocysticercosis diagnosis

Initial evaluation should include careful history, physical examination, and neuroimaging studies. Neurocysticercosis is commonly diagnosed with the routine use of diagnostic methods such as non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain 13.

Neurocysticercosis Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 recommend serologic testing with enzyme-linked immunotransfer blot as a confirmatory test in patients with suspected neurocysticercosis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests using crude antigens should be avoided because of poor sensitivity and specificity.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 suggest screening for latent tuberculosis infection in patients likely to require prolonged corticosteroids.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 suggest screening or empiric therapy for Strongyloides stercoralis in patients likely to require prolonged corticosteroids.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 recommend that all patients with neurocysticercosis undergo a fundoscopic examination before initiation of anthelminthic therapy.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 suggest that patients with neurocysticercosis who have probably acquired neurocysticercosis in a non-endemic area have their household members be screened for tapeworm carriage. Remark: This is a public health issue and can often be addressed by the local health department.

Imaging studies

CT findings vary as follows, depending on the stage of evolution of the infestation:

- Vesicular stage (viable larva): Hypodense, nonenhancing lesions

- Colloidal stage (larval degeneration): Hypodense/isodense lesions with peripheral enhancement and perilesional edema

- Nodular-granular stage: Nodular-enhancing lesions

- Cysticercotic encephalitis: Diffuse edema, collapsed ventricles, and multiple enhancing parenchymal lesions

- Active parenchymal stage: The scolex within a cyst may appear as a hyperdense dot

- Calcified stage: When the parasite dies, nodular parenchymal calcifications are seen

MRI is the imaging modality of choice for neurocysticercosis, especially for evaluation of intraventricular and cisternal/subarachnoidal cysts. Findings on MRI include the following:

- Vesicular stage: Cysts follow the CSF signal; T2 hyperintense scolex may be seen, with no edema and usually no enhancement

- Colloidal stage: Cysts are hyperintense to the CSF; there is surrounding edema, and the cyst wall enhances

- Nodular-granular stage: The cyst wall thickens and retracts, there is a decrease in edema, and nodular or ring enhancement is present

Lab studies

CSF analysis for neurocysticercosis is indicated in every patient presenting with new-onset seizures or neurologic deficit in whom neuroimaging shows a solitary lesion but does not offer a definitive diagnosis. CSF is contraindicated in cases of large cysts causing severe edema and displacement of brain structures, as well as in lesions causing obstructive hydrocephalus.

CSF findings include the following:

- Mononuclear pleocytosis

- Normal or low glucose levels

- Elevated protein levels

- High IgG index

- Oligoclonal bands, in some cases

- Eosinophilia (5-500 cells/µL); however, this also occurs in neurosyphilis and CNS tuberculosis 14

- CSF ELISA for neurocysticercosis has a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 65%

Other tests are as follows:

- Stool examination: 10-15% of neurocysticercosis patients have taeniasis

- Brain biopsy: Necessary only in extreme cases

Neurocysticercosis treatment

Treatment of neurocysticercosis depends upon the viability of the larval cysts of the tapeworm Taenia solium and its complications 15. Management includes symptomatic treatment as well as treatment directed against the tapeworm Taenia solium 16. If the tapeworm Taenia solium is dead, the approach is as follows:

- Treatment is directed primarily against the symptoms

- Anticonvulsants are used for management of seizures; monotherapy is usually sufficient

- Duration of the treatment remains undefined and depends neither on the type of seizure at presentation nor on other risk factors for recurrence, such as age at onset and number of seizures before diagnosis. The Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (2018) 13 recommend antiepileptic drugs for all patients with single enhancing lesions and seizures.

- Calcification remains an epileptogenic focus. In patients who have been seizure free for 6 months, the Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) suggest tapering off and stopping antiepileptic drugs after resolution of the lesion in patients with single enhancing lesion without risk factors for recurrent seizures. The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 suggest albendazole therapy rather than no antiparasitic therapy for all patients with single enhancing lesion.

- Treating patients with viable cysts with a course of anticysticercal drugs in order to achieve better control of seizures is common practice. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that in patients with seizures due to viable parenchymal cysts, antiparasitic therapy decreases the burden of parasites and is safe and effective, at least in reducing the number of seizures with generalization 17.

If the tapeworm Taenia solium is viable or active, treatment varies as follows:

- Patients with vasculitis, arachnoiditis, or encephalitis: A course of steroids or immunosuppressants is recommended before the use of anticysticercal drugs

- Antiparasitic treatment 18 with albendazole is also useful in cysticercosis of the racemose type (ie, multiple cysts in the basal cisterns). The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 recommend that patients treated with albendazole for more than 14 days be monitored for hepatotoxicity and leukopenia. The usual dose of albendazole is 15 mg/kg/day divided into two daily doses for 10–14 days with food. The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) recommend a maximum dose of 1,200 mg/day. The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) recommend albendazole (15 mg/kg/day) combined with praziquantel (50 mg/kg/day) for 10–14 days rather than albendazole monotherapy for patients with more than two viable parenchymal cysticerci. No additional monitoring is needed for patients receiving combination therapy with albendazole and praziquantel beyond that recommended for albendazole monotherapy.

- The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 suggest re-treatment with antiparasitic therapy for parenchymal cystic lesions persisting for 6 months after the end of the initial course of therapy.

- The Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018) 13 suggest that MRI be repeated at least every 6 months until resolution of the cystic component.

- Patients with parenchymal, subarachnoid, or spinal cysts and without complications (eg, chronic epilepsy, headaches, neurologic deficits related to strokes, and hydrocephalus): anticysticercal treatment can be considered, with the concomitant use of steroids

- Multiple trials with anticysticercal treatment may be required for giant subarachnoid cysts

- Patients with seizures due to viable parenchymal cysts: antiparasitic therapy 17

Indications for surgical intervention and recommended procedures are as follows:

- Hydrocephalus due to an intraventricular cyst: Placement of a ventricular shunt, followed by surgical extirpation of the cyst and subsequent medical treatment 19

- Multiple cysts in the subarachnoid space (ie, the racemose form): Urgent surgical extirpation

- Obstruction due to arachnoiditis: Placement of a ventricular shunt followed by administration of steroids and subsequent medical therapy.

- The management of patients with diffuse cerebral edema should be anti-inflammatory therapy such as corticosteroids, whereas hydrocephalus usually requires a surgical approach 13.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (2018) 13 recommend that patients with hydrocephalus from subarachnoid neurocysticercosis be treated with shunt surgery in addition to medical therapy.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (2018) 13 recommend corticosteroid treatment of patients with spinal neurocysticercosis with evidence of spinal cord dysfunction (eg, paraparesis or incontinence) or as adjunctive therapy along with antiparasitic therapy.

Long-Term Monitoring

Intracerebral cysticercotic lesions can cause epilepsy in the future. Administration of antiepileptic medication is the same as in any other epileptic syndrome.

Follow-up imaging study is recommended after 2-3 months following treatment, especially in cases in which anticysticercal medications are used as a diagnostic tool. The use of imaging will guide the requirement of future trials of anticysticercal medication in cases of subarachnoid cysticercosis.

Neurocysticercosis prognosis

In most patients with neurocysticercosis, the prognosis is good. Associated seizures seem to improve after treatment with anticysticercal drugs and, once treated, the seizures are controlled by a first-line antiepileptic agent. Duration of treatment, however, is not defined.

No figures are available for the burden of mortality associated with neurocysticercosis. However, the racemose eurocysticercosis which appears macroscopically as groups of cysticerci, often in clusters that resemble bunches of grapes located in the subarachnoid space—is associated with poor prognosis and elevated mortality rate (>20%) 20.

Neurocysticercosis-associated epilepsy is an important cause of neurologic morbidity 10 and chronic epilepsy is one of the most frequent complications of neurocysticercosis. Others include headaches, neurologic deficits related to strokes, and hydrocephalus. Patients with complications such as hydrocephalus, large cysts, multiple lesions with edema, chronic meningitis, and vasculitis are acutely ill and do not respond very well to treatment. Frequently, they have complications due to medical and surgical therapy.

References- International League Against Epilepsy. Relationship between epilepsy and tropical disease. Epilepsia. 1994;35:89–93.

- Bern C, Garcia HH, Evans C, Gonzalez AE, Verastegui M, Tsang VC, Magnitude of the disease burden from neurocysticercosis in a developing country. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1203–9.

- Medina MT, Rosas E, Rubio-Donnadieu F, Sotelo J. Neurocysticercosis as the main cause of late-onset epilepsy in Mexico. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:325–7.

- Nash TE, Garcia HH. Diagnosis and treatment of neurocysticercosis. (2011) Nature reviews. Neurology. 7 (10): 584-94. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.135

- Kimura-Hayama ET, Higuera JA, Corona-Cedillo R et-al. Neurocysticercosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30 (6): 1705-19. doi:10.1148/rg.306105522

- Teitelbaum GP, Otto RJ, Lin M et-al. MR imaging of neurocysticercosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153 (4): 857-66.

- Sheth TN, Pillon L, Keystone J et-al. Persistent MR contrast enhancement of calcified neurocysticercosis lesions. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19 (1): 79-82.

- Chaoshuang L, Zhixin Z, Xiaohong W, Zhanlian H, Zhiliang G. Clinical analysis of 52 cases of neurocysticercosis. Trop Doct. 2008 Jul. 38(3):192-4.

- White AC Jr. Neurocysticercosis: a major cause of neurological disease worldwide. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:101–15.

- Del Brutto OH, Santibanez R, Noboa CA, Aguirre R, Diaz E, Alarcon TA. Epilepsy due to neurocysticercosis: analysis of 203 patients. Neurology. 1992 Feb. 42(2):389-92.

- Barinagarrementeria F, Del Brutto OH. Lacunar syndrome due to neurocysticercosis. Arch Neurol. 1989 Apr. 46(4):415-7.

- Barinagarrementeria F, Cantu C. Neurocysticercosis as a cause of stroke. Stroke. 1992 Aug. 23(8):1180-1.

- Neurocysticercosis Clinical Practice Guidelines (2018). https://reference.medscape.com/viewarticle/906548

- Tian XJ, Li JY, Huang Y, Xue YP. Preliminary analysis of cerebrospinal fluid proteome in patients with neurocysticercosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009 May 5. 122(9):1003-8.

- Odermatt P, Preux PM, Druet-Cabanac M. Treatment of neurocysticercosis: a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008 Sep. 79(9):978.

- Garg RK. Treatment of neurocysticercosis: is it beneficial?. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2008 Aug. 6(4):435-40.

- White AC Jr. New developments in the management of neurocysticercosis. J Infect Dis. 2009 May 1. 199(9):1261-2.

- Garcia HH, Pretell EJ, Gilman RH, Martinez SM, Moulton LH, Del Brutto OH, et al. A trial of antiparasitic treatment to reduce the rate of seizures due to cerebral cysticercosis. N Engl J Med. 2004 Jan 15. 350(3):249-58.

- Rangel-Castilla L, Serpa JA, Gopinath SP, Graviss EA, Diaz-Marchan P, White AC Jr. Contemporary neurosurgical approaches to neurocysticercosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009 Mar. 80(3):373-8.

- Bickerstaff ER, Cloake PC, Hughes B, Smith WT. The racemose form of cerebral cysticercosis. Brain. 1952 Mar. 75(1):1-18.