Ober test

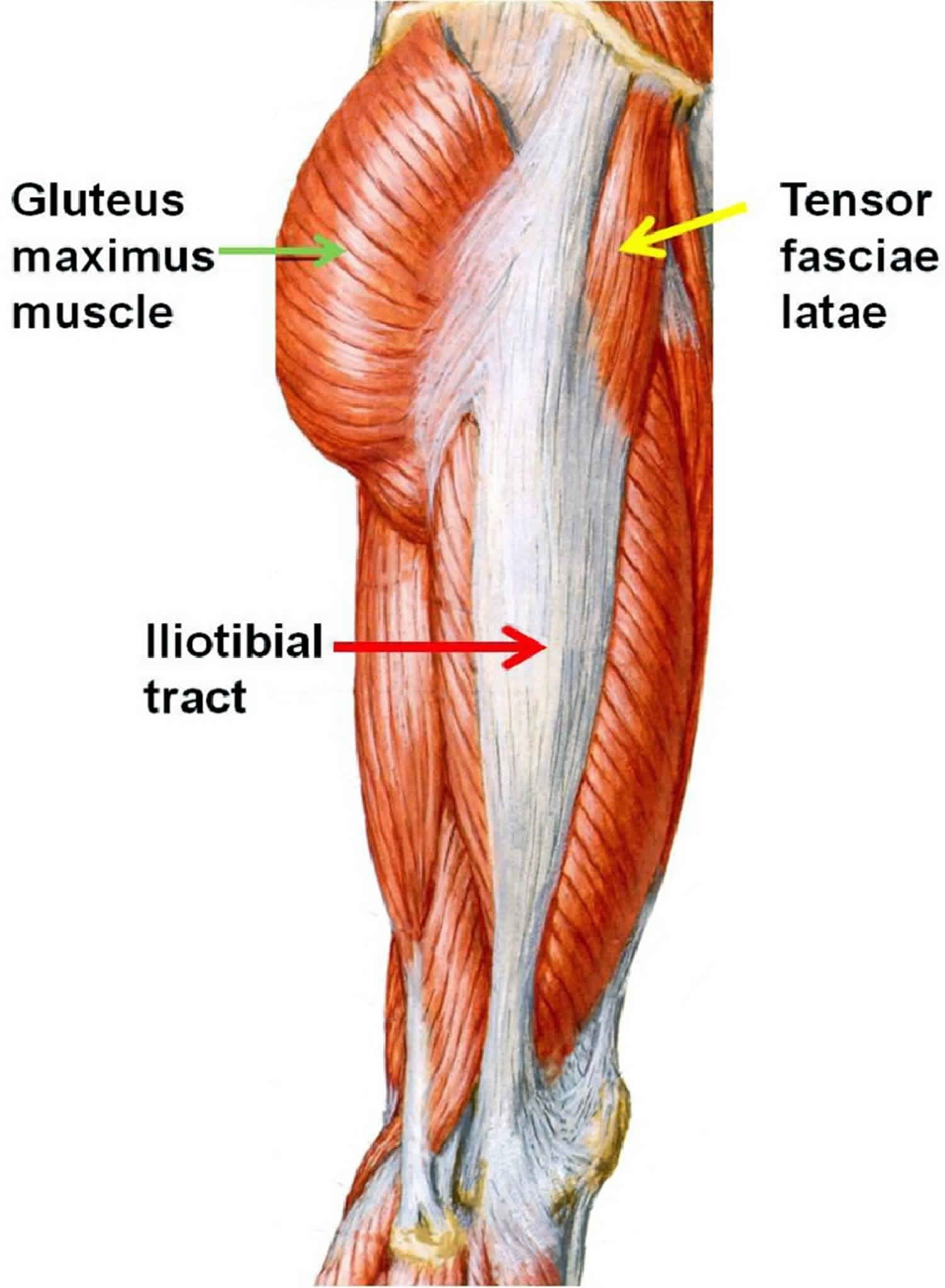

Ober’s test evaluates a tight, contracted or inflamed tensor fascia lata and iliotibial band (ITB). The Ober test or modified Ober test is the most commonly recommended physical examination tool for assessment of iliotibial band tightness 1. The iliotibial band is the condensation of fascia formed by the tensor fascia lata and the gluteus medius and minimus muscles. The iliotibial band is a wide, flat structure that originates at the iliac crest and inserts at the Gerdy tubercle on the lateral aspect of the proximal tibia. This band serves as a ligament between the lateral femoral condyle and the lateral tibia to stabilize the knee.

The iliotibial band assists in the following 4 movements of the lower extremity 2:

- Abducts the hip

- Contributes to internal rotation of the hip when the hip is flexed to 30°

- Assists with knee extension when the knee is in less than 30° of flexion

- Assists with knee flexion when the knee is in greater than 30° of flexion

The iliotibial band is not attached to bone as it courses between the Gerdy tubercle and the lateral femoral epicondyle. This lack of attachment allows it to move anteriorly and posteriorly with knee flexion and extension. Some authors hypothesize that this movement may cause the iliotibial band to rub against the lateral femoral condyle, causing inflammation. Other investigators hypothesize that injury of the iliotibial band results from compression of the band against a layer of innervated fat between the iliotibial band and epicondyle. Furthermore, a potential deep space is located under the iliotibial band as it crosses the lateral femoral epicondyle and travels to the Gerdy tubercle. This bursa may become inflamed and cause a clicking sensation as the knee flexes and extends. The inflamed bursa may add another component to iliotibial band tendinitis.

Iliotibial band syndrome is the most common cause of lateral knee pain among athletes 3. Iliotibial band syndrome develops as a result of inflammation of the bursa surrounding the iliotibial band and usually affects athletes who are involved in sports that require continuous running or repetitive knee flexion and extension 4. Iliotibial band syndrome is, therefore, most common in long-distance runners and cyclists. Iliotibial band syndrome may also be observed in athletes who participate in volleyball, tennis, soccer, football, skiing, weight lifting, and aerobics 5.

In runners, the posterior edge of the iliotibial band impinges against the lateral epicondyle of the femur just after foot strike in the gait cycle 6. This friction occurs at or slightly below 30 º of knee flexion 7. Downhill running and running at slower speeds may exacerbate iliotibial bandS as the knee tends to be less flexed at foot strike 8.

In cyclists, the iliotibial band is pulled anteriorly on the pedaling downstroke and posteriorly on the upstroke. The iliotibial band is predisposed to friction, irritation, and microtrauma during this repetitive movement because its posterior fibers adhere closely to the lateral femoral epicondyle.

The usual clinical history describes lateral knee pain:

- Pain with activity

- Typically, the patient with iliotibial band syndrome presents with an insidious onset of lateral knee pain that is present during running.

- Early in the course of the injury, the pain usually resolves after running.

- If the athlete continues to run, the pain may progress to being present during walking and between training sessions.

- Pain localized over the lateral femoral epicondyle

- The athlete is able to localize the lateral knee pain to approximately 2 cm above the lateral joint line.

- Untreated, the pain may eventually radiate to the distal tibia, calf, and up to the lateral thigh.

- Pain while climbing stairs or running downhill

- Pain is commonly experienced when the athlete climbs stairs or runs downhill.

- Pain may develop with any activity that places the knee in a weight-bearing position at approximately 30º of knee flexion.

- Pain at rest

- Pain at rest is usually associated with severe tendinitis, an associated lateral meniscus tear, an associated lateral femoral condyle bruise, or a cartilage injury.

- Any time there is pain at rest but no history of acute or repetitive trauma, the practitioner should ask questions to rule out neoplasm, infection, or inflammatory arthropathy.

- Willett, G. M., Keim, S. A., Shostrom, V. K., & Lomneth, C. S. (2016). An Anatomic Investigation of the Ober Test. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(3), 696–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546515621762

- Iliotibial Band Syndrome. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/91129-overview

- Ellis R, Hing W, Reid D. Iliotibial band friction syndrome–a systematic review. Man Ther. 2007 Aug. 12(3):200-8.

- Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, et al. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. J Anat. 2006 Mar. 208(3):309-16.

- van der Worp MP, van der Horst N, de Wijer A, Backx FJ, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2012 Nov 1. 42(11):969-92.

- Baker RL, Souza RB, Rauh MJ, Fredericson M, Rosenthal MD. Differences in Knee and Hip Adduction and Hip Muscle Activation in Runners With and Without Iliotibial Band Syndrome. PM R. 2018 Apr 26.

- Fredericson M, Wolf C. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: innovations in treatment. Sports Med. 2005. 35(5):451-9.

- Foch E, Milner CE. Frontal Plane Running Biomechanics in Female Runners with Previous Iliotibial Band Syndrome. J Appl Biomech. 2013 May 13.