Oral allergy syndrome

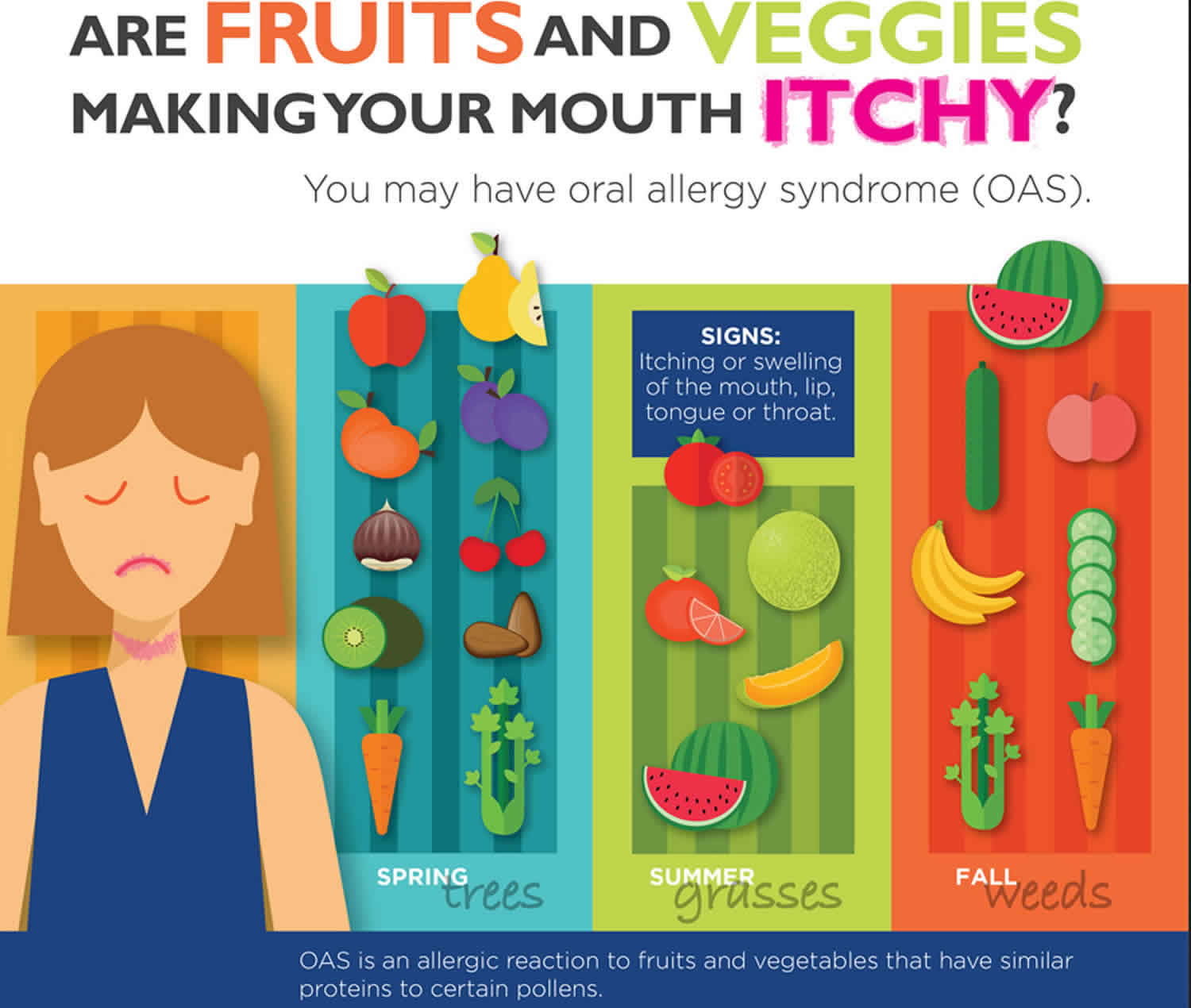

Oral allergy syndrome also called “pollen-food allergy syndrome” 1, “pollen-associated food allergy syndrome” 2, “birch pollen-related food allergy” 3, is a type of contact food allergic reaction brought about by contact of the mouth and throat with flavors, nuts, raw fruits, and vegetables 4. Some experts suggest that oral allergy syndrome may be a collection of symptoms resulting from pollen-food syndrome or another food allergy 5. Oral allergy syndrome is an allergic reaction to fruits and vegetables that have similar proteins to certain pollens. The most well-known symptoms include itchiness or swelling of the mouth, face, lips, tongue and throat, which starts rapidly after a raw fruit or vegetable is placed in the mouth, and that, as a rule, continues for just a couple of minutes after the food has been swallowed. Although in rare cases, the reaction can occur more than an hour later. Moreover, other foods have been implicated, such as legumes and nuts, and symptoms may persist beyond the oral cavity 6. Itching, tingling, and/or swelling of the lips, tongue, palate, or throat are typical 2 and, although considered rare, severe reactions have also been reported, including anaphylaxis 7.

The oral allergy syndrome is a remarkably common sign of food allergy, mainly in adults who are allergic to tree pollen 8. Oral allergy syndrome includes oral itching, lip swelling, and laryngeal angioedema after contact with allergenic foods 9. Infrequently, oral allergy syndrome may trigger severe swelling of the throat that causes difficulty swallowing and/or breathing. Anaphylaxis may be initiated by a pollen cross-reactive raw vegetable or fruit; nevertheless, this occurrence is extremely infrequent 10. Patients who have oral signs seem to show that the capacity exists for advancement to a further systemic reaction, and restriction of the diet would be correctly advised. Heating food does not change the allergic capability of those specific food allergens 11.

Foods that may cause oral allergy syndrome:

- Apple, Apricot, Carrot, Celery, Cherry, Kiwi, Peach, Pear, Plum, Almond and Hazelnut

- Cantaloupe, Honeydew, Orange, Tomato, Watermelon

- Banana, Cantaloupe, Carrot, Celery, Cucumber, Honeydew, Peach, Watermelon, Zucchini

Pollen allergy:

- Spring tree pollen: Birch

- Summer grass pollen: Timothy and Orchard

- Fall weed pollen: Mugwort and Ragweed

Oral allergy syndrome is generally considered to be a mild form of food allergy. Rarely, oral allergy syndrome can cause severe throat swelling leading to difficulty swallowing or breathing. In a person who is highly allergic, a systemic reaction, called anaphylaxis, may be caused by a pollen cross-reactive raw fruit or vegetable, but this is very uncommon. Oral allergy syndrome can occur at any time of the year.

The frequency of oral allergy syndrome with pollen allergy has been reported as 5-8%; 1-2% of patients with oral allergy syndrome with pollen allergy show extreme responses, e.g., anaphylaxis. Birch tree pollen, ragweed pollen, and grass pollen hypersensitivity cause the symptoms.

Although there is no definitive test for oral allergy syndrome, affected individuals often have a positive allergy skin test result triggered by the food’s fresh extract or blood test for specific pollen, along with a history of symptoms after ingestion of the suspected foods. Oral challenge result is normally positive with the raw food and negative with the similar cooked food.

In the pediatric population, oral allergy syndrome is predominantly found in adolescent populations 12; oral allergy syndrome is more characteristic in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis 13. Ma et al 14 revealed that the frequency of oral allergy syndrome in patients with pollen allergy was 5–8%; 20% of allergists reported that a small number of patients show advanced systemic reactions; 30% of allergists never recommended epinephrine for oral allergy syndrome, and 3% routinely did recommend epinephrine when necessary.

Oral allergy syndrome treatment include:

- Avoiding raw-foods that cross react with your pollen allergens.

- Taking oral antihistamines medications to relieve mild symptoms.

- Bake or cook foods to degrade the proteins and eliminate the cross reaction.

- Eat canned fruits or vegetables during your pollen season

- Peel the fruit, as the protein is often concentrated in the skin

See your allergist when the oral allergy syndrome symptoms get worse or occur when eating nuts.

Oral allergy syndrome causes

Oral allergy syndrome is brought about by food allergens; for the most part, these are “uncooked fruits and raw vegetables” that contact the patient’s oropharynx 15. The allergic foods that trigger oral allergy syndrome are effectively inactivated by the corrosive action of the stomach, so the response typically ends when the food is swallowed. Thus, as a result, oral allergy syndrome seldom causes serious or life-endangering responses. Cooking or warming additionally attenuates the allergens, so cooked or canned foods seldom trigger oral allergy syndrome symptoms 15.

Certain customary samples of foods that trigger oral allergy syndrome are recorded, alongside the kind of pollen that is identified with these foods 15:

- Birch tree pollen hypersensitivity. The patients may experience oral symptoms after the ingestion of apricot, peach, apple, carrot, almond, plum, hazelnut, pear, celery, fennel, parsley, aniseed, coriander, soybean, caraway, or peanut 15. Birch allergy can often be related to oral allergy syndrome. Betv1 is the chief birch allergen 4.

- Ragweed-pollen hypersensitivity. The patients may experience oral symptoms after eating banana, melon, cucumber, or kiwi 15.

- Grass-pollen hypersensitivity. The patients may be used to perioral and oral symptoms and signs after the ingestion of orange, tomato, melon, or peanut. Also, irritated and red hands may be observed after peeling raw potato 15. Oral allergy syndrome develops in individuals with pollen allergy. Allergens in raw vegetables, fruits, and nuts resemble the pollen allergens 4.

Even though numerous foods are recorded for each of the pollens mentioned above, many patients with oral allergy syndrome respond to only one or few of these foods 15.

Oral allergy syndrome pathophysiology

In oral allergy syndrome, typical signs are associated with contact to food antigens and IgE-induced release of mediators. With regard to food intolerance that does not produce a positive radioallergosorbent test or skin test result, it seems appropriate to think about non–IgE-mediated causes 16. Oral allergy syndrome is sometimes accompanied by a systemic reaction and is considered to be an IgE-mediated allergy 17. Experimental reports emphasized particular elements that prevent improvement in oral tolerance that may similarly be involved in humans. Such elements include the apoptosis of T cells that are antigen specific, paralysis of the T cells, and deficiency in generation of T cells that are regulatory 18.

The interferon γ cytokine is also encoded in humans 19. In fetal life, the T-helper (Th) type 2 cell cytokine pattern prevails. This predominance may prevent harm to the placenta by Th1 cells. If the Th2 profile persists after delivery, then this would contribute to the absence of development of oral tolerance 20. Microbial life is established in the gut quickly after delivery, which creates a strong provocation to shifting toward a Th1 cell-mediated response 21. The so-called hygiene theory proposes avoiding antibacterial treatment that might itself be responsible for the expansion in allergy 22. Another essential component is the specific variation in IgE-mediated reaction. For example, a polymorphism in the CD14 gene is related to food allergy and elevated amounts of IgE 23. Furthermore, T-cell immuno-globulin mucin-1 (TIM-1) encoded by atopy susceptibility gene (Havcrl) is related to the control of Th1 and Th2 immune reactions. The evidence of a relationship between atopy and TIM-1 seems to show another application of the hygiene hypothesis 24.

Oral allergy syndrome symptoms

Oral allergy syndrome symptoms occur immediately after eating certain raw fruits, vegetables, or nuts and are usually limited to the mouth and throat. The most common symptoms include: itching or swelling of the mouth, lip, tongue, or throat. Paraesthesia; angioedema of the oral mucosa, tongue, palate, and oropharynx angioedema; and voice hoarseness can be seen. Oral allergy syndrome occurs in 47–70% of patients with pollen allergy 15. Oral allergy syndrome is an immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated allergic response. Homologous proteins and cross-responding antigenic determinants in pollens and in different vegetables and fruits may initiate the symptoms 25. Patients with sensitivity to birch antigens frequently have a response to “crisp apple, celery, cherry, hazelnuts, and carrot,” whereas patients sensitized to ragweed may respond to “melons, kiwi, and banana” 26. Symptoms are generally localized to the oropharynx and oral mucosal manifestations; throat pruritus or angioedema may occur 27. oral allergy syndrome symptoms may worsen during pollen seasons. Most patients with oral allergy syndrome are able to tolerate cooked, processed and peeled forms of these foods.

The main symptoms of oral allergy syndrome are itching and mild swelling of the lips, mouth, and throat 15. More unusual symptoms are the ones that do not affect the mouth and throat, such as itching, slight swelling or redness of the hands, nausea or stomach irritation (10%), vomiting, diarrhea, chest tightness, or loss of consciousness 28. Manifestations of oral allergy syndrome may vary according to the pollen season. Symptoms are typically most evident during the associated pollen season and for a few months afterward. Likewise, oral allergy syndrome symptoms might be particular to one fruit 15.

All individuals with oral allergy syndrome have a pollen allergy. Pollen allergy causes nasal symptoms (watery nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, sneezing, itching), eye symptoms (itching and swelling around the eyes), throat and ear symptoms (sore throat, voice changes, tingling in the ears), and sleep problems (frequent arousing, daytime fatigue) that happen at the same period every year 15.

Allergic manifestations are usually limited to the oropharyngeal region, such as swelling of the lips, tongue, and throat. Approximately 9% of individuals have symptoms at the oropharynx, and 1–2% of individuals with oral allergy syndrome present with severe responses, e.g., angioedema and anaphylaxis 29. The response is created via “heat-labile food proteins,” which cause cross-reactivity via the pollen proteins that cause allergy 16. Those reactions usually occur in individuals exposed to “birch-tree dust” after ingestion of “crude apples, fruits, potatoes, hazelnuts, carrots, and kiwis.” In addition, individuals allergic to “ragweed” respond to “banana and crisp melons” 30.

Oral allergy syndrome is typically diagnosed from responses to vegetables and fruits. oral allergy syndrome is sometimes inappropriately used when mild oral symptoms are actually pointing to seriously allergic responses to foods (i.e., shellfish or nuts) 14. In the study by Ma et al 14 about the prescribing habits of allergists for a child with nut sensitivity, 13% gave a conclusion of oral allergy syndrome and 25% did not count epinephrine. Similarly, 20% reported that they used the term oral allergy syndrome for systemic manifestations brought on by fruit 14.

Oral allergy syndrome used to be thought to be a self-limiting phenomenon related to ingestion of raw protein 31. Silviu-Dan and Melanson 32 evaluated 26 patients with oral allergy syndrome to decide the risk of anaphylaxis separately from the oropharyngeal difficulties that occur after eating the specific protein. Six of the patients had extreme anaphylactic responses that required acute treatment 32. Patients with oral allergy syndrome who had anaphylaxis had the same likelihood of allergic rhinitis or asthma as patients with oral allergy syndrome without anaphylaxis 32.

Mild symptoms from eating nuts may indicate a more severe food allergy with a risk of anaphylaxis. See an allergist if you have symptoms after eating nuts.

Risk factors for anaphylactic responses are:

- having a systemic response to the food,

- responding to the cooked form of the food,

- skin-prick test positivity to the food extract,

- lack of sensitization to the associated pollen,

- allergy to peach 9.

When fruit allergy develops without pollen allergy, responses will probably be extreme 9. In one review, 82% of the patients with food allergy and without allergic rhinitis showed systemic responses, (i.e., 36% experienced anaphylaxis); conversely, 45% of patients with allergic rhinitis had systemic responses and 9% experienced anaphylactic reactions 33.

Oral allergy syndrome diagnosis

The diagnosis of oral allergy syndrome is undertaken by clinical history and by skin-prick test positivity with fresh food extracts. The oral challenge result is positive with the raw food and negative with the cooked food 13. Assessment of an individual with pollen-food allergy syndrome should incorporate a careful medical history to decide which foods trigger the symptoms and are responsible for the responses, tests that may incorporate skin-prick test with fresh or raw fruits, and possibly oral food challenges. If there is a systemic response and diagnostic laboratory data, the food ought to be prevented, and epinephrine should be prescribed. Assessment for other associated foods ought to be undertaken 34.

The diagnostic exactness of skin-prick test with artificial extracts is highly variable. Now and again, skin-prick tests that use the food in its common form are more trustworthy, particularly for plant food allergy 35. The indicative value of the specific IgE depends on the concentrate used 36. Skin-prick tests give prompt outcomes that permit a straightforward clinical assessment and are less expensive than in vitro techniques. Because of cross-reactivity, both strategies may give false positivity. For example, patients oversensitive to grass pollen ordinarily have IgE-specific reactions to oat, however, with no symptoms 37. There have been some efforts to relate IgE-antibody levels to double-blind placebo controlled food challenge results. Double-blind placebo controlled food challenge is currently the criterion standard for a definite diagnosis of IgE-mediated allergy 38.

Elimination diets

Elimination diets may be valuable in individuals with continuing symptoms. Positive food testing results to skin-prick test and/or radioaller-gosorbent test and cases suspected from the medical history are confirmable. Twenty-one days are typically adequate to cast reliable doubt on food allergy. The outcome is viewed as positive if a steady improvement of the symptoms occur. If the symptoms return once foods are reestablished, a double-blind placebo controlled food challenge should be accomplished 39.

Double-blind placebo controlled food challenge

The double-blind placebo controlled food challenge is the principal approved test for food allergy diagnosis 40. Because the technique is complicated and has a long duration, the test is restricted to individuals being evaluated for perpetual avoidance of foods fundamental to a healthy diet, e.g., milk, eggs. In patients with past serious food responses, the double-blind placebo controlled food challenge test is contraindicated. The tested food is prepared in opaque capsules, or in its normal shape veiled by an inactive component. The dummy treatment consists of a case of using an item of similar appearance that contains dextrose or other inactive food components that are certain to be tolerated by the individual and permit satisfactory concealment of the administered food 41.

Food patch test

Food patch tests were, until recently, in use for the analysis of food allergy, including delayed signs. For pediatric patients who experience atopic dermatitis, including delayed responses, a food patch test improves diagnostic accuracy, yet not at the expense of sensitivity or speed 42. This technique was not approved for routine diagnosis. Despite the fact that numerous reports support the usefulness of “lymphocytes proliferation and cytokine increment” after exposure to food allergens, there is no affirmation of benefit over the customary analytic method 39.

Lactose breath test

Diagnosis of lactose intolerance depends on the peak in breath hydrogen (H2) after lactose intake that is used for the breath-test analysis 39.

Cross-reactivity

Allergic cross-reactivity is the situation in which IgE antibodies initially recognized as the epitopes of one allergic reaction are found to cause comparable problems in a further allergy 39. More than 65% of food allergens consist of just four basic species: (1) the Bet v1 homologs, (2) the profilins, (3) the cereal prolamin superfamily, and (4) the cupins 43. This might indicate broad IgE cross-reactivity, even among allergens that occur in systematically distinct plants. Moreover, IgE binding may happen if up to 35–40% of the amino acid sequence is conserved 39.

Oral allergy syndrome treatment

There is no “cure” for the oral allergy syndrome 11. Food allergy treatment depends on antihistamines, corticosteroids, and epinephrine (intramuscular). No clear evidence exists for using sodium cromoglycate 39. “Specific immune therapy” for food allergy is not feasible. Specific immune therapy that used peanuts was discontinued because of excessively high levels adverse effects 44. Novel encouraging immunologic investigations of mice include the utilization of recombinant allergens and the use of the allergen mixed with heat killed listeria as an adjuvant 45.

Monoclonal humanized antibodies of anti-IgE may be used to counter severe food allergy. IgE receptor antibodies of the mast cells that lack cell degranulation might obstruct the allergic response. Initial studies demonstrate that anti-IgE treatment can, in essence, enlarge the threshold amount of peanut protein necessary to incite allergic symptoms in individuals with peanut allergy 46. The utilization of anti-IgE treatment in combination with specific immune therapy might be a valuable therapy in the future 47.

Although serious responses are rarely encountered, intramuscular use of an epinephrine autoinjector (e.g., EpiPen, Epinephrine Auto-injector) may be advised 11. Food allergy-induced asthma encompassed 9.5% of individuals and asthma that occurred singly was recognized in just 2.8% of patients. Food allergy-induced asthma is potentially life threatening, which leads to prescribing epinephrine autoinjectors and bronchodilators 48.

Oral allergy syndrome diet

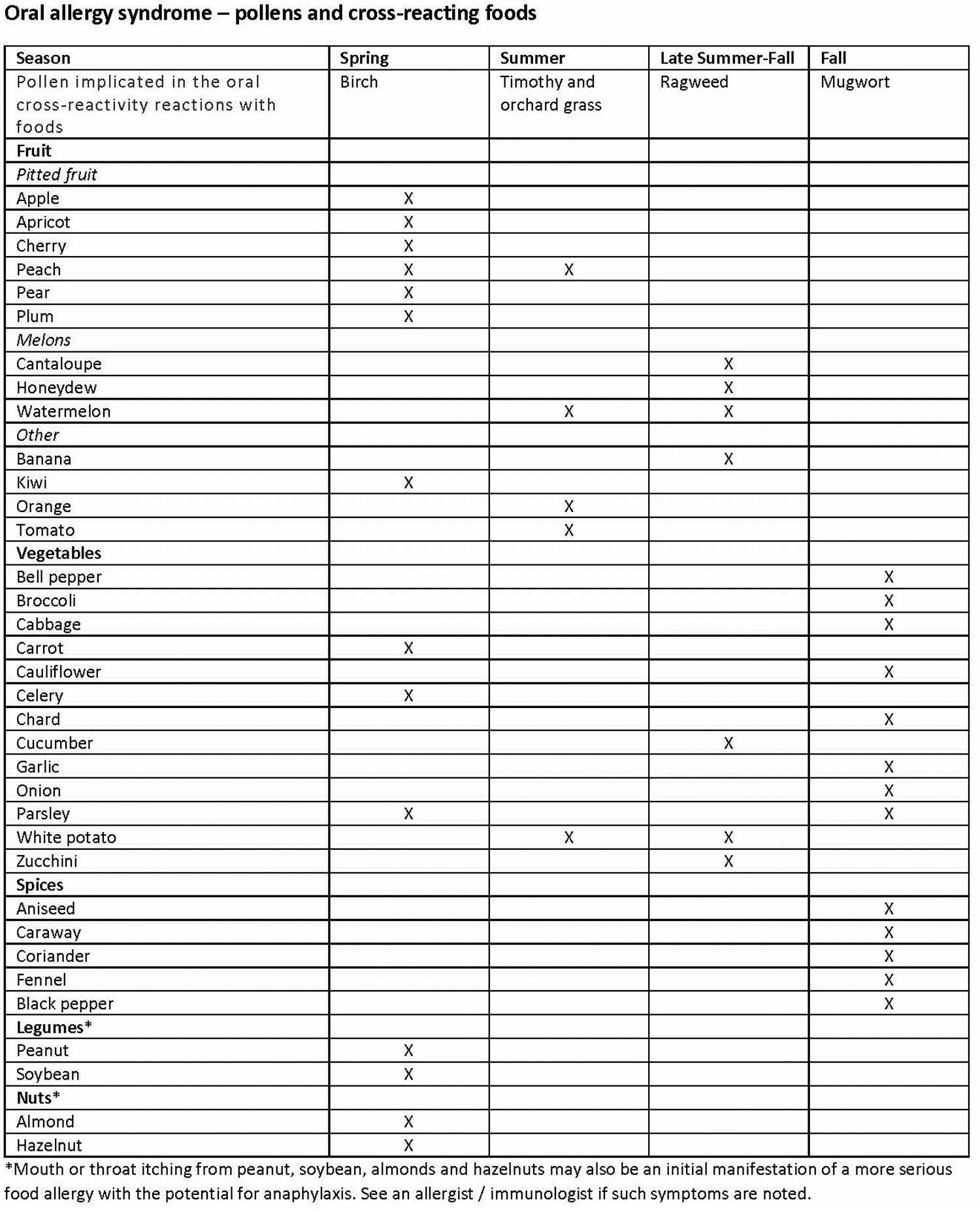

Some people report symptoms with only one food and others with many different fruits and vegetables. Some people report that only certain varieties of the fruit cause symptoms, for example specific apple varieties. In the case of oral allergy syndrome, individuals react to different foods based on what type of seasonal allergies they are affected by. For instance, if you are allergic to birch tree pollen, a primary airborne allergen responsible for symptoms in the springtime, you may have reactions triggered by pitted fruit or carrot. Even peanuts, almond, and hazelnut may cause mouth itching in those with birch pollen allergy. If mouth itching is noted with nuts, you should see an allergist /immunologist because mild mouth symptoms may signal a more serious allergic reaction to nuts. People with allergies to grasses may have a reaction to peaches, celery, tomatoes, melons (cantaloupe, watermelon and honeydew) and oranges. Those with reactions to ragweed might have symptoms when eating foods such as banana, cucumber, melon, and zucchini. This convenient table lists the possible pollen and plant food cross-reactivities.

If you have symptoms of oral allergy syndrome, avoid eating these raw foods, especially during allergy season because in many patients, oral allergy syndrome worsens during the pollen season of the pollen in question. One way to reduce cross-reactions with food is to bake or microwave the food because high temperatures break down the proteins responsible for oral allergy syndrome. Eating canned food may also limit the reaction. And, peeling the food before eating may be helpful, as the offending protein is often concentrated in the skin.

Figure 1. Oral allergy syndrome food list

References- Joneja, J.V. Oral allergy syndrome. in: The Health Professional’s Guide to Food Allergies and Intolerances. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Chicago, IL; 2012: 310–316

- Boyce, J.A., Assa’ad, A., Burks, A.W. et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126: S1–S58

- Geroldinger-Simic, M., Zelniker, T., Aberer, W. et al. Birch pollen-related food allergy: Clinical aspects and the role of allergen-specific IgE and IgG4 antibodies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 127: 616–622

- Muluk, N. B., & Cingi, C. (2018). Oral Allergy Syndrome. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy, 32(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2018.32.4489

- Brown, C.E. and Katelaris, C.H. The prevalence of the oral allergy syndrome and pollen-food syndrome in an atopic paediatric population in south-west Sydney. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014; 50: 795–800

- Kelava, N., Lugović-Mihić, L., Duvancić, T., Romić, R., and Šitum, M. Oral allergy syndrome—The need of a multidisciplinary approach. Acta Clin Croat. 2014; 53: 210–219

- Webber, C.M. and England, R.W. Oral allergy syndrome: A clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic challenge. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010; 104: 101–108

- Pastorello, E.A. , Ortolani, C. Oral allergy syndrome. In: Metcalfe, DD , Sampson, HA , Simon, RA , editors. Food allergy: adverse reactions to foods and food additives. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science. 2003; 169–182.

- Pastorello, E.A. , Farioli, L. , Pravettoni, V. The major allergen of peach (Prunus persica) is a lipid transfer protein. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 103: 520–526.

- Oral Allergy Syndrome (OAS) or Pollen Fruit Syndrome (PFS). https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/library/allergy-library/outdoor-food-allergies-relate

- Oral Allergy Syndrome (Food Pollen Syndrome). http://concordallergyandasthma.com/oral_allergy_syndrome.pdf

- Brown, C.E. , Katelaris, C.H. The prevalence of the oral allergy syndrome and pollen-food syndrome in an atopic paediatric population in south-west Sydney. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014; 50: 795–800.

- Reda, S.M. Gastrointestinal manifestations of food allergy. Pediatr Health. 2009; 3: 217–229.

- Ma, S. , Sicherer, S.H. , Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. A survey on the management of pollen-food allergy syndrome in allergy practices. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 112: 784–788.

- Patient education: Oral allergy syndrome (Beyond the Basics). https://www.uptodate.com/contents/oral-allergy-syndrome-beyond-the-basics

- Amlot, P.L. , Kemeny, D.M. , Zachary, C. , Parkes, P. , Lessof, M.H. Oral allergy syndrome (OAS): symptoms of Ig-E mediated hypersensitivity to food. Clin Allergy. 1987; 17: 33–42.

- Yamamoto, T. , Asakura, K. , Shirasaki, H. , Himi, T. Clustering of food causing oral allergy syndrome in patients with birch pollen allergy. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 2008; 111: 588–593.

- Hoyne, G.F. , Le Roux, I. , Corsin-Jimenez, M. Serratel-induced notch signalling regulates the decision between immunity and tolerance made by peripheral CD4 (+) T cells. Int Immunol. 2000; 12: 177185.

- MacDonald, T.T. , Monteleone, G. IL-12 and Th1 immune responses in human Peyer’s patches. Trends Immunol. 2001; 22: 244–247.

- Holt, P.G. , Sly, P.D. , Bjorksten, B. Atopic versus infectious diseases in childhood: A question of balance? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1997; 8: 53–58.

- Neurath, M.F. , Finotto, S. , Glimcher, L.H. The role of Th1/Th2 polarization in mucosal immunity. Nat Med. 2002; 8: 567–573.

- Strachan, D.P. Hay fever, hygiene and household size. BMJ. 1989; 299: 1259–1260.

- Woo, J.G. , Assa’ad, A. , Heizer, A.B. , Bernstein, J.A. , Hershey, G.K. The -159 C-T polymorphism of CD14 is associated with nonatopic asthma and food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 112: 438–444.

- Umetsu, S.E. , Lee, W.L. , McIntire, J.J. TIM-1 induces T cell activation and inhibits the development of peripheral tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2005; 6: 447–454.

- Kazemi-Shirazi, L. , Pauli, G. , Purohit, A. Quantitative IgE inhibition experiments with purified recombinant allergens indicate pollen-derived allergens as the sensitizing agents responsible for many forms of plant food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000; 105: 116125.

- Eriksson, N.E. , Wihl, J.A. , Arrendal, H. Birch-pollen related food hyper-sensitivity: influence of total and specific IgE levels. A multicenter study. Allergy. 1983; 38: 353–357.

- Ortolani, C. , Ispano, M. , Pastorello, E. , Bigi, A. , Ansaloni, R. The oral allergy syndrome. Ann Allergy. 1988(pt 2); 61: 47–52.

- Ortolani, C. , Pastorello, E.A. , Farioli, L. IgE-mediated allergy from vegetable allergens. Ann Allergy. 1993; 71: 470–476.

- Sicherer, S.H. Food allergy. Lancet. 2002; 360: 701–710.

- Sicherer, S.H. , Sampson, H.A. 9. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117(suppl Mini-Primer): S470–S475.

- Food Allergy: New Insights and Management Strategies. https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/420552

- Silviu-Dan, F. , Melanson, M. Oral allergy syndrome: A warning? Program and abstracts of the 56th annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; March 3–8, 2000; San Diego, Calif. Abstract 566.

- Fernandez-Rivas, M. , van Ree, R. , Cuevas, M. Allergy to Rosaceae fruits without related pollinosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997; 100: 728733.

- Crespo, J.F. , Rodriguez, J. , James, J.M. , Daroca, P. , Reano, M. , Vives, R. Reactivity to potential cross-reactive foods in fruit-allergic patients: implications for prescribing food avoidance. Allergy. 2002; 57: 946–949.

- Sampson, H.A. , Munoz-Furlong, A. , Bock, S.A. Symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 115: 584–591.

- Ortolani, C. , Ispano, M. , Pastorello, E.A. , Ansaloni, R. , Magri, G.C. Comparison of results of skin prick tests (with fresh foods and commercial food extracts) and RAST in 100 patients with oral allergy syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989; 83: 683–690.

- Jones, S.M. , Magnolfi, C.F. , Cooke, S.K. , Sampson, H.A. Immunologic cross-reactivity among cereals grains and grasses in children with food hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995; 96: 341–351.

- Sampson, H.A. Utility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 107: 891896.

- Ortolani, C. , Pastorello, E.A. Food allergies and food intolerances. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006; 20: 467–483.

- Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C. , Ortolani, C. , Aas, K. Adverse reactions to food. European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology Subcommittee. Allergy. 1995; 50: 623–635.

- Bindslev-Jensen, C. , Ballmer-Weber, B.K. , Bengtsson, U. Standardization of food challenges in patients with immediate reactions to foods—position paper from the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2004; 59: 690–697

- Roehr, C.C. , Reibel, S. , Ziegert, M. , Sommerfeld, C. , Wahn, U. , Niggemann, B. Atopy patch test, together with determination of specific IgE levels, reduce the need for oral food challenges in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 107: 548–553.

- Jenkins, J.A. , Griffiths-Jones, S. , Shewry, P.R. , Breiteneder, H. , Mills, E.N. Structural relatedness of plant food allergens with specific reference to cross reactive allergens: An in silico analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 115: 163–170.

- Nelson, H.S. , Lahr, J. , Rule, R. , Bock, A. , Leung, D. Treatment of anaphylactic sensitivity to peanuts by immunotherapy with injections of aqueous peanut extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997; 99: 744–751.

- Sampson, H.A. Immunological approaches to the treatment of food allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2001; 12(suppl 14): 91–96.

- Leung, D.Y. , Shanahan, W.R. , Li, X.M. , Sampson, H.A. New approaches for the treatment of anaphylaxis. Novartis Found Symp. 2004; 257: 248–260; discussion 260–264, 276–285.

- Asero, R. Effects of birch pollen-specific immunotherapy on apple allergy in birch pollen-hypersensitive patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998; 28: 1368–1373.

- Rancé, F. , Dutau, G. Asthma and food allergy: report of 163 pediatric cases. Arch Pediatr. 2002; 9(suppl 3): 402s–407s.