Primary peritoneal cancer

Primary peritoneal cancer is a relatively rare cancer that starts in the thin layer of tissue lining the inside of the abdomen called the peritoneum and develops most commonly in women. Primary peritoneal cancer is very rare in men. Most people are over the age of 60 when they are diagnosed. Primary peritoneal cancer is a close relative of epithelial ovarian cancer, which is the most common type of malignancy that affects the ovaries. Primary peritoneal cancer cells are the same as the most common type of ovarian cancer cells. This is because the lining of the abdomen and the surface of the ovary come from the same tissue when you develop from embryos in the womb. So doctors treat primary peritoneal cancer in the same way as ovarian cancer. The cause of primary peritoneal cancer is unknown, but it is important for women to know that it is possible to have primary peritoneal cancer even if your ovaries have been removed.

American cancer research suggests that around 10 out of 100 (around 10%) of all women with ovarian, fallopian and peritoneal serous cancers have primary peritoneal cancer.

The abdominal cavity and the entire surface of all the organs in the abdomen are covered in a cellophane-like, glistening, moist sheet of tissue called the peritoneum. It not only protects the abdominal organs, it also supports and prevents them from sticking to each other and allows them to move smoothly within the abdomen. The cells of the peritoneal lining develop from the same type of cell that lines the surface of the ovary and fallopian tube for that matter. Certain cells in the peritoneum can undergo transformation into cancerous cells, and when this occurs, the result is primary peritoneal cancer. It can occur anywhere in the abdominal cavity and affect the surface of any organ contained within it. It differs from ovarian cancer because the ovaries in primary peritoneal cancer are usually only minimally affected with cancer.

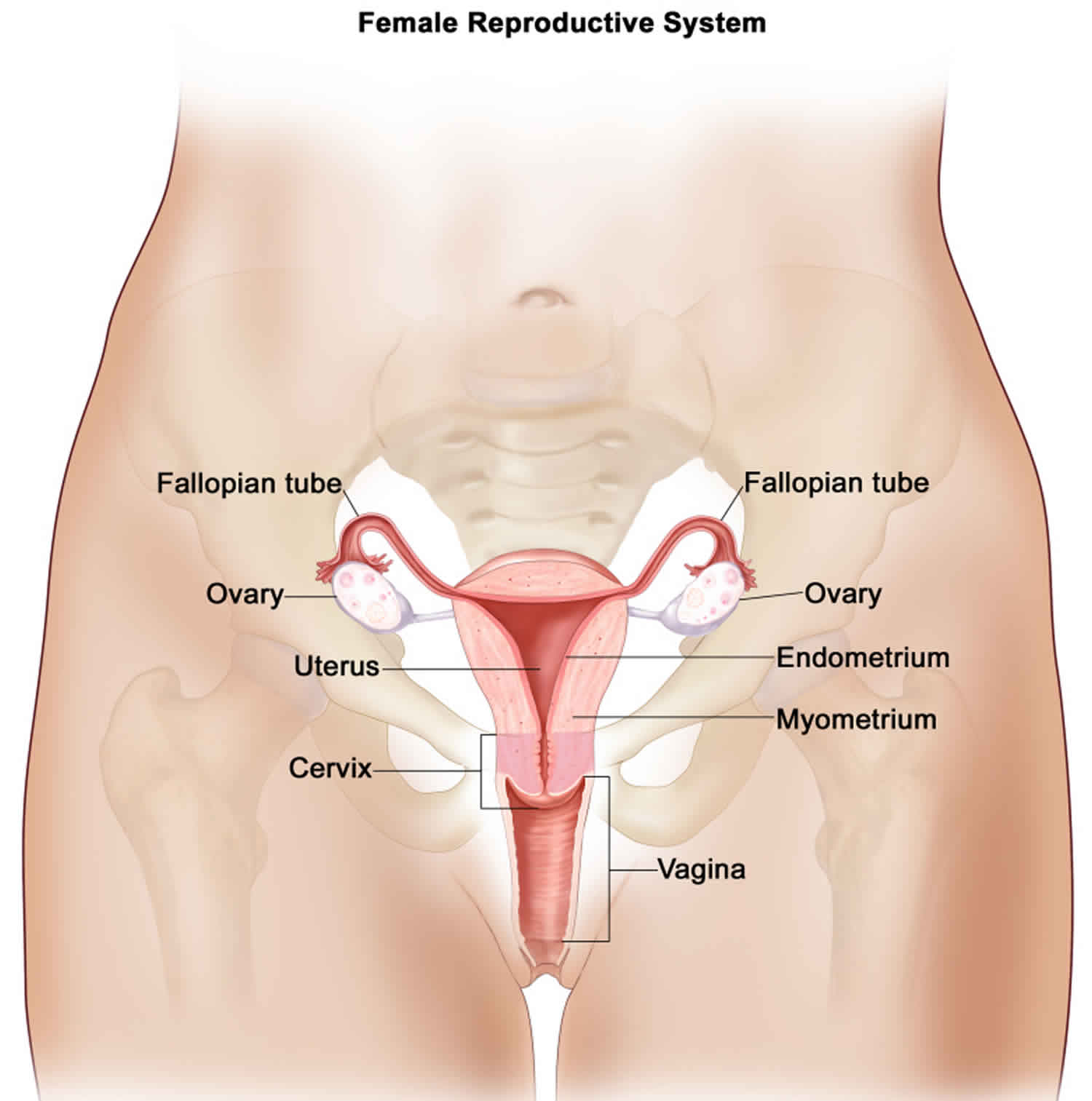

The fallopian tubes are a pair of floppy tube-like structures that originate at the top (fundus) of the uterus where they communicate with the endometrial cavity and course away from the uterus, on either side, towards the ovaries where they “flop” over the ovaries with their finger-like (fimbriated) end. Cancers of the fallopian tube are also relatively rare and very closely related to cancers of the ovary and primary peritoneal cancer. They share many commonalities and emerging data is even suggesting that many of the previously felt to be ovarian cancers may indeed have been fallopian tube cancer.

Although the clinical presentation of fallopian tube cancer is very similar to ovarian cancer and primary peritoneal cancer, there are some differences. Cancers of the fallopian tube arise within the inside (lumen) of the fallopian tube and typically cause it to swell like a sausage. The involvement of the ovary is secondary, but it is usually so extensive that one cannot tell whether it began on the ovary and spread to the fallopian tube, or vice versa. Because of that, many fallopian tube cancers may have been classified as ovarian cancers. As the fallopian tube swells with cancer, it produces fluid, similar to ascites, that can “leak” back into the uterus and lead to a watery vaginal discharge, the classic presentation of fallopian tube cancer when associated with an adnexal mass.

The treatment you have depends on a number of things including:

- the size of your cancer

- where the cancer is in the abdomen, and if it has spread further away

- your general health

The treatment for primary peritoneal cancer is the same as for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer.

The aim of treatment for advanced cancer is usually to shrink the cancer and control it for as long as possible. You might have the following treatments.

Surgery

The aim of surgery is to remove as much of the cancer from the abdomen as possible before chemotherapy. This is called debulking surgery.

Chemotherapy tends to work better when there are only small tumors inside the abdomen. The surgery usually includes removing your womb, ovaries, fallopian tubes and the layer of fatty tissue called the omentum.

The surgeon will also remove any other cancer that they can see at the time of surgery. This could include part of the bowel if the cancer has spread there.

Sometimes primary peritoneal cancer can grow so that it blocks the bowel or the urinary system. You might need surgery to unblock these if this happens.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses anti cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy cancer cells. These drugs work by disrupting the growth of cancer cells. The drugs circulate in the bloodstream around the body.

You may have chemotherapy:

- before surgery to reduce the size of the cancer

- after surgery when you have recovered

- on its own if you are unable to have surgery

The most common chemotherapy drugs used to treat primary peritoneal cancer are a combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel (Taxol).

Radiation therapy

Radiotherapy uses high energy x-rays to kill cancer cells. Radiotherapy isn’t often used for primary peritoneal cancers. But doctors may use it to shrink tumours and reduce symptoms.

Other treatments

You can have treatment to control symptoms, such as pain and fluid in the abdomen (ascites), even if you are unable to have chemotherapy.

Fluid can build up between the two layers of the peritoneum. It can be very uncomfortable and heavy.

Your doctor can drain the fluid off using a procedure called abdominal paracentesis or an ascitic tap. The diagram below shows this.

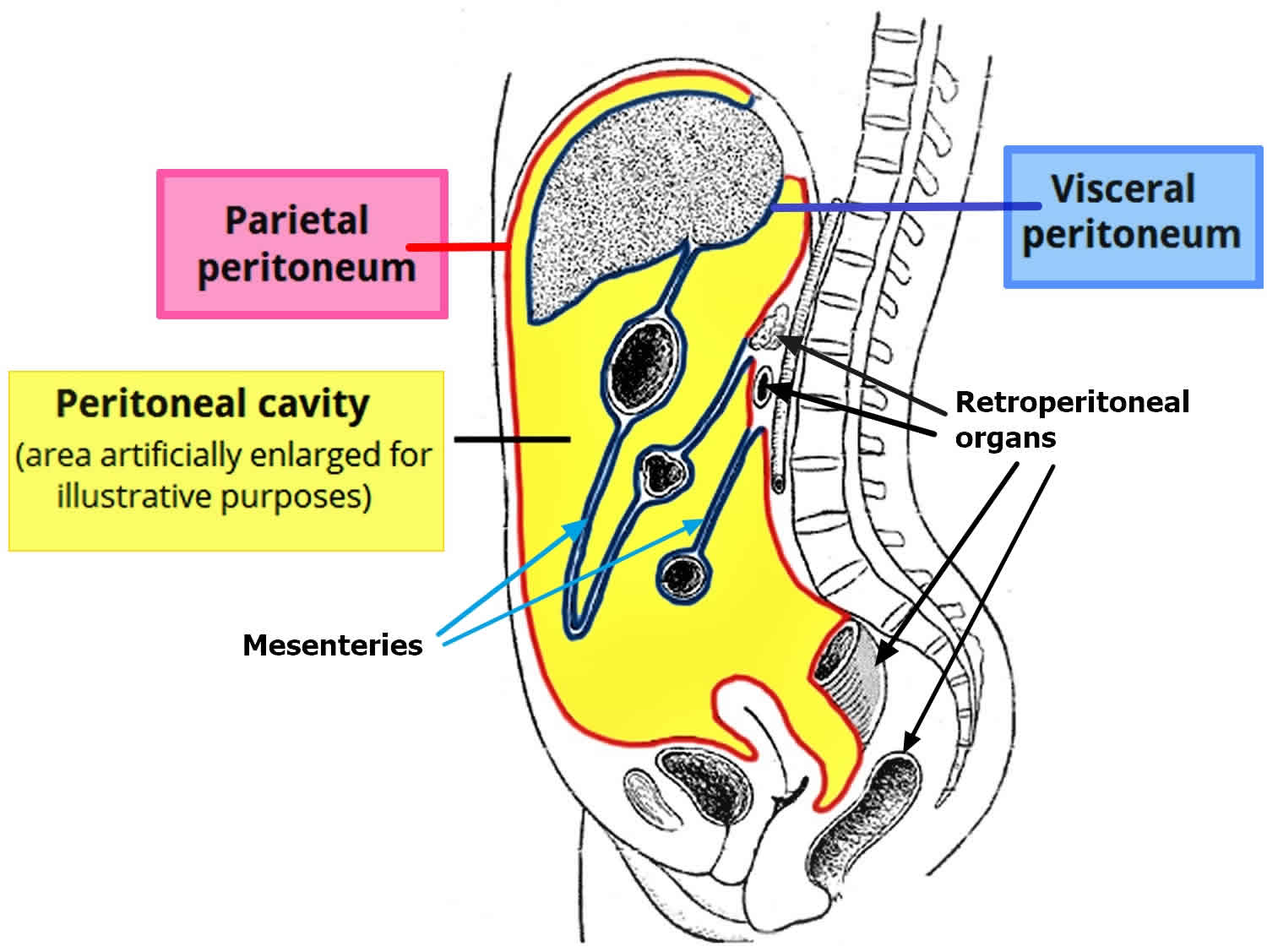

What is the peritoneum?

The peritoneum covers all of the organs within the tummy (abdomen), such as the bowel and the liver. It protects the organs and acts as a barrier to infection. The peritoneum has 2 layers. One layer lines the abdominal wall and is called the parietal layer. The other layer covers the organs and is called the visceral layer.

There is a small amount of fluid between the two layers, which separates them and allows them to slide over each other. This fluid allows us to move around without causing any friction on the layers.

Figure 1. Peritoneal cavity

Peritoneal metastasis

Peritoneal metastasis

Metastatic cancer to the peritoneum also known as peritoneal carcinomatosis, is more common than a primary peritoneal cancer. Peritoneal involvement is most common with cancers of the gastrointestinal (GI), reproductive and genitourinary tracts 1. Ovarian, colon, and gastric cancers are by far the most common conditions presenting in advanced stages with peritoneal metastasis. Cancers involving other organs such as the pancreas, appendix, small intestine, endometrium, and prostate can also cause peritoneal metastasis, but such occur less frequently. While peritoneal carcinomatosis can arise from extra-abdominal primary malignancies, such cases are uncommon; and they account for approximately 10% of diagnosed cases of peritoneal metastasis 2. Examples include breast cancer, lung cancer, and malignant melanoma. Ovarian cancer is the most common neoplastic disease-causing peritoneal metastasis in 46% of cases owing to the anatomic location of the ovaries and their close contact with the peritoneum as well as the embryological developmental continuity of ovarian epithelial cells with peritoneal mesothelial cells 3.

- Colorectal cancer patients also contribute to a higher number of patients with peritoneal involvement due to the high incidence of these cancers overall. About 7% of cases develop synchronous peritoneal metastasis 4.

- Approximately 9% of non-endocrinal pancreatic cancer cases present with peritoneal cancer.

- Gastric carcinoma tends to reach an advanced stage at first presentation, and 14% of such cases can have peritoneal metastasis 5.

- A neuroendocrine tumor arising from the gastrointestinal tract (GI-NET) is a slow-growing neoplasm, and it can metastasize to the peritoneum. peritoneal cancer can occur in about 6% of gastrointestinal-neuroendocrine tumor patients 6. Its frequency increases with age.

- Peritoneal carcinomatosis from extra-abdominal malignancy presents in only 10% of cases, where metastatic breast cancer (41%), lung cancer (21%) and malignant melanoma (9%) account for the majority of the cases 2.

- Lung cancer is the primary cause of newly diagnosed cancers worldwide accounting for over a million new cases per year. However, peritoneal carcinomatosis in lung cancer is rare and occurs in about 2.5 to 16% of autopsy results. Considering the scale of lung cancer rates globally, it could be the reason for a higher number of peritoneal carcinomatosis cases worldwide 7.

- Sometimes it is difficult to find the primary tumor site. In such cases, we have peritoneal carcinomatosis with an unknown primary. About 3 to 5% of cases of peritoneal carcinomatosis are of unknown origin 8.

Historically, the presence of metastatic deposits in the peritoneal cavity implied an incurable, fatal disease where curative surgical therapy was no longer a reasonable option. Newer surgical techniques and innovation in medical management strategies have dramatically changed the course of the disease over the past years. Effective treatment approaches have evolved, allowing for improvements in disease-free and overall survival 9.

Peritoneal metastasis treatment

Recent advancements in surgical techniques and favorable outcomes related to targeted chemotherapy have encouraged the aggressive treatment of peritoneal cancer whenever it is feasible and accessible. Complete cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) and systemic chemotherapy has become the mainstay treatment for peritoneal carcinomatosis (peritoneal cancer) originating from most gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts carcinomas. The efficacy of this treatment was validated in 2003 by a randomized clinical trial that compared complete cytoreductive surgery combined with HIPEC versus systemic chemotherapy alone (median survival: 22.3 vs. 12.6 months) 10. Macroscopically complete complete cytoreductive surgery (CRS-R0) is a major prognostic factor, with 5-year survival rates as high as 45% compared to less than 10% when complete cytoreductive surgery is incomplete 11. Dr. Sugarbaker 12 changed the perception relating to peritoneal carcinomatosis from being terminal cancer to being a loco-regional disease and recommended an aggressive surgical approach with complete cytoreductive surgery, given the positive survival benefits.

The first step in the management centers on appropriate patient selection for surgery.

Patient selection:

- Patient characteristics: age, co-morbidities, general condition, and functional status. The objective is to determine the fitness of the patient for the anticipated trauma of surgery and its perioperative impact.

- Exclude generalized metastatic disease: As pointed in the diagnostic section, CT and/or MRI or sometimes PET/CT can be used to investigate potential distal metastases depending on the type of cancer. Possible sites to look for are thorax, spine bones, brain, etc.

- The extent of the peritoneal disease:

CT/MRI is the primary investigation tool to determine the size, extent, and type of peritoneal lesions. peritoneal cancerI scoring system described in Figure 1 is routinely used to determine the surgical resectability and possibly favorable prognosis. Diagnostic laparoscopy provides very accurate estimates for peritoneal cancerI along with probable completeness of the cytoreduction (CC) index and outcome assessment in terms of disease-free survival, overall survival and quality of life. Involvement of the small bowel impacts the peritoneal cancerI score and can suggest a bad prognosis. The following are the usual surgical sites used for preoperative determination of the extent of the disease for exclusion from complete cytoreductive surgery 13:

- Massive mesenteric root infiltration not amenable to complete cytoreduction

- Significant pancreatic capsule infiltration or pancreatic involvement requiring major resection not feasibly or amenable to complete surgical cytoreduction

- More than one-third small bowel length involvement requiring resection

- Extensive hepatic metastasis

Some surgeons advocate the use of peritoneal surface disease severity score (PSDSS) for the early preoperative assessment of the prognosis based on the symptoms, peritoneal cancerI index, and Primary tumor histology. However, extensive study results are needed to implement it on a regular practice 13.

Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyper Thermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

Upon the determination of patient fitness for surgery with selection driven by feasibility criteria, complete cytoreductive surgery is performed commonly through an open abdominal wall incision approach along with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. This novel treatment option became a reality for surgeons through the extensive work of Dr. Sugarbacker 14 suggested surgical techniques. Cytoreductive surgery includes peritonectomy and individualized manual resection of the tumor lesions from different areas of the abdominal wall and mesentery. Peritonectomy now classifies as a curative treatment method for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, with the latter viewed as the locoregional spread instead of systemic disease. The usual surgical intention for any cancer treatment is the removal of all cancer cells through en-block resections with clear margins. However, for peritoneal carcinomatosis, it is highly difficult to achieve complete removal of malignant cells. The idea behind cytoreduction is to reach complete removal of any macroscopic lesions, and simultaneous use of Hyper Thermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) would potentially remove microscopic cancer lesions 12. This technical approach has shown tremendous survival benefits along with disease-free survival and improved quality of life in patients. Currently, complete cytoreductive surgery combined with Hyper Thermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a first-line treatment for appendiceal and colorectal cancer-related peritoneal carcinomatosis 15. It has also shown a promising role in ovarian, gastric and neuroendocrine tumors 16.

Complication related to complete cytoreductive surgery:

- Postoperative complications such as bleeding, infection, bowel obstruction, hemorrhage or peritonitis.

Complication related to hyper thermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC):

- Oxaliplatin is used with dextrose solutions, so it could potentially contribute to postoperative acidosis and hyperglycemia

- Mitomycin C can cause neutropenia in about one-third of patients

- Other gastrointestinal side effects

Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC)

This newer innovative therapeutic intervention has potential use in patients with extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis who may be deemed unresectable or unfit for surgery. The basis for aerosol chemotherapy is the premise that the intraabdominal application of chemotherapeutic drugs under pressure could potentially enhance tissue penetration and increases distribution 17. It has also been found to have superior benefits of drug delivery to tumor tissue with a significant effect on tumor regression than conventional intraperitoneal chemotherapy or systemic chemotherapy 18. This treatment option is beneficial in patients with extraperitoneal metastases in which this method could work as an effective palliative treatment option. Further ongoing prospective trials will decide on its future role and regular use.

Primary peritoneal cancer causes

The causes of primary peritoneal cancer are unknown. Most cancers are caused by a number of different factors working together. Research suggests that a very small number of primary peritoneal cancers may be linked to the inherited faulty genes BRCA 1 and BRCA 2. These are the same genes that increase the risk of ovarian cancer and breast cancer.

Primary peritoneal cancer symptoms

Symptoms for primary peritoneal cancer can be very unclear and difficult to spot. Many of the symptoms are more likely to be caused by other medical conditions.

Unfortunately, because of the vague nature of the signs, primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer are usually diagnosed in advanced stages of disease, when achieving a cure is difficult.

The typical symptoms of both are more commonly gastrointestinal rather than gynecologic in nature, and include:

- Abdominal bloating

- Changes in bowel habits

- Early feeling of fullness after eating

- Bloating and when severe, nausea and vomiting may result

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Feeling or being sick

- Feeling bloated

- Loss of appetite

Occasionally, patients can present with a blockage of the intestines related to tumor on or next to the bowels. Vaginal bleeding is infrequently seen in patients with primary peritoneal cancer, but may be a little more common in patients with fallopian tube cancer.

Primary peritoneal cancer diagnosis

Both primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer are usually diagnosed when a woman sees her doctor complaining of abdominal swelling and bloating. As described above, the symptoms of either cancer are more commonly gastrointestinal than gynecologic in nature. These symptoms are related to the accumulation of fluid, also known as ascites, that commonly occurs with either cancer. Gastrointestinal symptoms also occur because seedlings of tumor often line the peritoneal surface (the outer lining) of the intestines, a process called carcinomatosis. The omentum, an apron of fatty tissue that hangs down from the colon and stomach, often contains bulky tumor, described as omental caking. Although omental cakes can be detected on a physical exam, they frequently are subtle and difficult to detect. When a woman is found to have fluid in the abdomen (ascites), the usual first step toward a diagnosis is a CT scan. This is a special type of x-ray test that allows doctors to assess the entire abdomen and pelvis. Omental caking and ascites, as well as other tumor growths, are commonly seen, and point toward the diagnosis of primary peritoneal cancer, fallopian tube cancer or ovarian cancer. Other cancers can cause these findings, thus, further tests are needed and are usually focused around ruling out other more common cancers, such as colon and breast cancer.

Frequently, the evaluation of ascites begins with a procedure known as a paracentesis, whereby fluid is removed from the abdomen using a needle. The fluid is examined under the microscope, looking for the presence of cancerous cells. Unfortunately, this procedure is not without risks as the process of performing a paracentesis can actually “seed” the abdominal wall with cancer cells. Therefore, it is important to seek the advice of a gynecologic oncologist when considering this procedure as it may not be necessary given that most patients with these findings will undergo surgery regardless of the results. However, it may be helpful in the patient who is either not a surgical candidate, or in one suspected of having ascites for reasons other than cancer, such as liver or heart disease. Sometimes fluid is even drawn off because of patient discomfort until surgery or chemotherapy can be scheduled.

There are several blood tests that are frequently performed when either primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer is suspected. The most common of which is the CA 125 blood test. CA 125 is a chemical that is made by tumor cells and is usually elevated in patients with primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer. Unfortunately, it can also be elevated in a variety of benign conditions, as well as other cancers, and thus an elevated CA 125 blood test does not mean the patient has a cancer. More recently a newer blood test, HE4, can also be used as it is less likely elevated than CA 125 in benign conditions. You can read more about CA 125 with our brochure, CA 125 Levels: Your Guide.

The actual diagnosis of primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer is often not completely certain until a woman undergoes surgery. This is because the clinical presentation of either disease is so similar to that of epithelial ovarian cancer. primary peritoneal cancer, fallopian tube cancer and ovarian cancer appear identical under the microscope. It is the pattern of tumor distribution and organ involvement in the abdominal cavity that indicates the origin of the primary cancer. Patients with fallopian tube cancer usually have gross involvement of the fallopian tubes with lesser involvement of the ovaries. Patients with primary peritoneal cancer are usually found to have normal ovaries, or only superficial involvement of the ovaries, at the time of pre-surgical imaging tests or at time of surgery. However, the diagnosis can occasionally remain uncertain even following surgery.

Surgical staging

Surgical staging of cancers is performed in order to fully assess the extent of disease. This allows for decisions to be made regarding additional therapy, which is usually in the form of chemotherapy. Surgical staging generally involves removal of all visible disease, as well as removal of the ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus. It can also include removal of the omentum, lymph nodes and other organs depending on the surgical findings.

While there is no formal agreed-upon staging system for primary peritoneal cancer, because it is so similar to ovarian cancer with respect to treatment, tumor state is typically assigned using guidelines established for ovarian cancer.

Stages 1 through 4 describe how far the tumor has spread. Nearly all patients diagnosed will have stage 3 or higher because warning signs are typically few until the cancer is widespread. Patients with primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer may have fluid around the lungs, known as a pleural effusion. If an effusion is present, some fluid may be removed in order to look for tumor cells. If tumor cells are found in this fluid, the patient has stage 4 disease.

Ovarian cancer stages

The 2 systems used for staging ovarian cancer, the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) system and the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) TNM staging system are basically the same.

They both use 3 factors to stage (classify) this cancer :

- The extent (size) of the tumor (T): Has the cancer spread outside the ovary or fallopian tube? Has the cancer reached nearby pelvic organs like the uterus or bladder?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to the lymph nodes in the pelvis or around the aorta (the main artery that runs from the heart down along the back of the abdomen and pelvis)? Also called para-aortic lymph nodes.

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to fluid around the lungs (malignant pleural effusion) or to distant organs such as the liver or bones?

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

The staging system in the table below uses the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage). It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. This is also known as surgical staging. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests done before surgery.

The system described below is the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system effective January 2018. It is the staging system for ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and primary peritoneal cancer.

Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 1. Ovarian cancer stages

| AJCC Stage | Stage grouping | FIGO Stage | Stage description* |

| I | T1 N0 M0 | I | The cancer is only in the ovary (or ovaries) or fallopian tube(s) (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IA | T1a N0 M0 | IA | The cancer is in one ovary, and the tumor is confined to the inside of the ovary; or the cancer is in one fallopian tube, and is only inside the fallopian tube. There is no cancer on the outer surfaces of the ovary or fallopian tube. No cancer cells are found in the fluid (ascites) or washings from the abdomen and pelvis (T1a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IB | T1b N0 M0 | IB | The cancer is in both ovaries or fallopian tubes but not on their outer surfaces. No cancer cells are found in the fluid (ascites) or washings from the abdomen and pelvis (T1b). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IC | T1c N0 M0 | IC | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes and any of the following are present:

It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| II

| T2 N0 M0 | II | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes and has spread to other organs (such as the uterus, bladder, the sigmoid colon, or the rectum) within the pelvis or there is primary peritoneal cancer (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIA | T2a N0 M0 | IIA | The cancer has spread to or has invaded (grown into) the uterus or the fallopian tubes, or the ovaries. (T2a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIB | T2b N0 M0 | IIB | The cancer is on the outer surface of or has grown into other nearby pelvic organs such as the bladder, the sigmoid colon, or the rectum (T2b). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIA1 | T1 or T2 N1 M0 | IIIA1 | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or there is primary peritoneal cancer (T1) and it may have spread or grown into nearby organs in the pelvis (T2). It has spread to the retroperitoneal (pelvic and/or para-aortic) lymph nodes only. It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIA2 | T3a N0 or N1 M0 | IIIA2 | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or there is primary peritoneal cancer and it has spread or grown into organs outside the pelvis. During surgery, no cancer is visible in the abdomen (outside of the pelvis) to the naked eye, but tiny deposits of cancer are found in the lining of the abdomen when it is examined in the lab (T3a). The cancer might or might not have spread to retroperitoneal lymph nodes (N0 or N1), but it has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIB | T3b N0 or N1 M0 | IIIB | There is cancer in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or there is primary peritoneal cancer and it has spread or grown into organs outside the pelvis. The deposits of cancer are large enough for the surgeon to see, but are no bigger than 2 cm (about 3/4 inch) across. (T3b). It may or may not have spread to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (N0 or N1), but it has not spread to the inside of the liver or spleen or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIC | T3c N0 or N1 M0 | IIIC | The cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or there is primary peritoneal cancer and it has spread or grown into organs outside the pelvis. The deposits of cancer are larger than 2 cm (about 3/4 inch) across and may be on the outside (the capsule) of the liver or spleen (T3c). It may or may not have spread to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (N0 or N1), but it has not spread to the inside of the liver or spleen or to distant sites (M0). |

| IVA | Any T Any N M1a | IVA | Cancer cells are found in the fluid around the lungs (called a malignant pleural effusion) with no other areas of cancer spread such as the liver, spleen, intestine, or lymph nodes outside the abdomen (M1a). |

| IVB | Any T Any N M1b | IVB | The cancer has spread to the inside of the spleen or liver, to lymph nodes other than the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and/or to other organs or tissues outside the peritoneal cavity such as the lungs and bones (M1b). |

Footnotes:

* The following additional categories are not described in the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Primary peritoneal cancer treatment

Both primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer are treated in the same way as ovarian cancer is treated. They are most often treated with surgery and chemotherapy—only rarely is radiation therapy used. Your specific treatment plan will depend on several factors, including:

- Stage and grade of the cancer

- Size and location of the cancer

- Your age and general health

All treatments for either cancer have side effects. Most side effects can be managed or avoided. Treatments may affect unexpected parts of your life, including your function at work, home, intimate relationships and deeply personal thoughts and feelings.

Before beginning treatment, it is important to learn about the possible side effects and talk with your treatment team members about your feelings or concerns. They can prepare you for what to expect and tell you which side effects should be reported to them immediately. They can also help you find ways to manage the side effects you experience.

Surgery

Surgery is usually the first step in treating primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer and it should be performed by a gynecologic oncologist. The goal of the surgery is the removal of all visible disease because this approach has been shown to improve survival. This process is known as “debulking” surgery. When all visible disease is removed, or if only small tumor implants (less than 1 cm in diameter) remain, the patient is considered optimally debulked. Occasionally, the location of tumor within the abdomen or the condition of the patient does not allow for optimal debulking surgery to be performed. In this situation, chemotherapy may be given first and the patient might have surgery at a later time. Most surgery is performed using a procedure called a laparotomy during which the surgeon makes a long cut in the wall of the abdomen, although they are also commonly found at laparoscopy. If either primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer is found, the gynecologic oncologist performs the following procedures:

- Salpingo-ooophorectomy: both ovaries and fallopian tubes are removed.

- Hysterectomy: the uterus is removed usually with the attached cervix.

- Omentectomy: the omentum, a fatty pad of tissue that covers the intestines, is removed.

Occasionally, some of the nearby lymph nodes will be removed. Depending on the surgical findings, more extensive surgery, including removal of portions of the small or large intestine and removal of tumor from the liver, diaphragm and pelvis, may be performed. Removal of as much tumor as possible is one of the most important factors affecting cure rates.

Side effects of surgery

Some discomfort is common after surgery. It often can be controlled with medicine. Tell your treatment team if you are experiencing pain. Other possible side effects are:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Infection, fever

- Wound problem

- Fullness due to fluid in the abdomen

- Shortness of breath due to fluid around the lungs

- Anemia

- Swelling caused by lymphedema, usually in the legs or arms

- Blood clots

- Difficulty urinating or constipation

- Talk with your doctor if you are concerned about any of the problems listed.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. It can be given intravenously (injected into a vein) or, more recently, intraperitoneal administration has become popular because it is associated with a longer survival in patients with a very similar cancer, ovarian cancer. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves the administration of medicines directly into the abdomen through a catheter which is placed under the skin at the time of initial surgery, or shortly thereafter. Unfortunately, it has more immediate side effects than intravenous chemotherapy and therefore some patients prefer the more traditional intravenous administration. Intraperitoneal treatment is only given if optimal debulking surgery has been achieved. Either treatment may be administered in the doctor’s office, outpatient treatment areas of the hospital or, occasionally, as an inpatient.

Traditionally, intravenous chemotherapy is given every three weeks as an outpatient. Each treatment of chemotherapy is known as a cycle and initial treatment usually consists of six cycles. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is also given on an every three-week schedule for six cycles. Each cycle is a little more involved as the patient might receive treatments on several days of the 21 day cycle compared to receiving treatments on only day 1 of the cycle if given intravenously.

The most commonly used chemotherapy medicines for primary peritoneal cancer are the same as those used for ovarian cancer. These include one of the platinum-based medicines, Cisplatin or Carboplatin, as well as Taxane (Paclitaxel or Taxotere) in combination.

Side effects of chemotherapy

Each person responds to chemotherapy differently. Some people may have very few side effects while others experience several. Most side effects are temporary. They include:

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Mouth sores

- Increased chance of infection

- Bleeding or bruising easily

- Vomiting

- Hair loss

- Fatigue

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy may be utilized for treatment of isolated small areas of disease that has returned after initial therapy. It is rarely used as a first therapy for either primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer.

Other treatments

You can have treatment to control symptoms, such as pain and fluid in the abdomen (ascites), even if you are unable to have chemotherapy.

Fluid can build up between the two layers of the peritoneum. It can be very uncomfortable and heavy.

Your doctor can drain the fluid off using a procedure called abdominal paracentesis or an ascitic tap. The diagram below shows this.

Follow up after treatment

After initial treatment is completed, patients with either cancer are followed closely with visits every two to four months for the first three years and then every six months for another two years or so and ultimately yearly. At each visit they have a physical exam, including a pelvic exam, CA 125 testing, and, depending on the patient and her situation, imaging tests, such as CT scans, X-rays, MRIs or PET scans, may be performed. Unless patients are diagnosed early these cancers have a tendency to recur with time. Hence, patients often require more than one round of chemotherapy and may also need additional surgical procedures.

Recurrent disease

Recurrences are common in patients with primary peritoneal cancer or fallopian tube cancer because most patients with either cancer are diagnosed when they already have advanced stages of disease. The majority of patients will initially go into remission, but the disease commonly returns months to years later when the CA 125 levels begins to rise, or new masses are found on physical exam or imaging studies. Unfortunately, the prognosis for this cancer is not favorable once it recurs, but a longer remission before recurrence is associated with a better chance for a second, third and even fourth remission.

There are several treatment options for patients who recur, depending on the location of recurrence, time since the initial therapy and the patient’s overall health status. These options include repeat surgery, re-treatment with the same chemotherapy that was given initially or a different type of agent. Radiation therapy can also be considered for selected cases. Each recurrence is different, so their treatment must be individualized based on a variety of factors including those listed above. Unfortunately, once a recurrence is diagnosed, one must re-focus the goals of treatment to help prolong quality of life rather than a cure.

Primary peritoneal cancer survival rate

Survival rates can give you an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful.

Keep in mind that survival rates are estimates and are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had a specific cancer, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. These statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk with your doctor about how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your situation.

A relative survival rate compares people with the same type and stage of cancer to people in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of ovarian cancer is 30%, it means that people who have that cancer are, on average, about 30% as likely as people who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed.

These numbers are based on people diagnosed with cancers of the ovary (or fallopian tube) between 2008 and 2014. These survival rates differ based on the type of ovarian cancer (invasive epithelial, stromal, or germ cell tumor).

Table 2. Invasive epithelial ovarian cancer

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) stage | 5-year relative survival rate |

| Localized | 92% |

| Regional | 75% |

| Distant | 30% |

| All SEER stages combined | 47% |

Footnote:

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread. But other factors, such as your age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment, can also affect your outlook.

- People now being diagnosed with ovarian (or fallopian tube) cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

- Desai JP, Moustarah F. Cancer, Peritoneal Metastasis. [Updated 2019 Jun 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541114

- Flanagan M, Solon J, Chang KH, Deady S, Moran B, Cahill R, Shields C, Mulsow J. Peritoneal metastases from extra-abdominal cancer – A population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018 Nov;44(11):1811-1817.

- Lengyel E. Ovarian cancer development and metastasis. Am. J. Pathol. 2010 Sep;177(3):1053-64.

- Quere P, Facy O, Manfredi S, Jooste V, Faivre J, Lepage C, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology, Management, and Survival of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis from Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2015 Aug;58(8):743-52.

- Gill RS, Al-Adra DP, Nagendran J, Campbell S, Shi X, Haase E, Schiller D. Treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: a systematic review of survival, mortality, and morbidity. J Surg Oncol. 2011 Nov 01;104(6):692-8.

- Madani A, Thomassen I, van Gestel YRBM, van der Bilt JDW, Haak HR, de Hingh IHJT, Lemmens VEPP. Peritoneal Metastases from Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Incidence, Risk Factors and Prognosis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017 Aug;24(8):2199-2205.

- Sereno M, Rodríguez-Esteban I, Gómez-Raposo C, Merino M, López-Gómez M, Zambrana F, Casado E. Lung cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Oncol Lett. 2013 Sep;6(3):705-708.

- Thomassen I, Verhoeven RH, van Gestel YR, van de Wouw AJ, Lemmens VE, de Hingh IH. Population-based incidence, treatment and survival of patients with peritoneal metastases of unknown origin. Eur. J. Cancer. 2014 Jan;50(1):50-6.

- Klos D, Riško J, Stašek M, Loveček M, Hanuliak J, Skalický P, Lemstrová R, Mohelníková BD, Študentová H, Neoral Č, Melichar B. Current status of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the multimodal treatment of peritoneal surface malignancies. Cas. Lek. Cesk. 2018 Dec 17;157(8):419-428.

- Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Sloothen GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, Zoetmulder FA. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003 Oct 15;21(20):3737-43.

- Verwaal VJ, Bruin S, Boot H, van Slooten G, van Tinteren H. 8-year follow-up of randomized trial: cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008 Sep;15(9):2426-32.

- Sugarbaker PH. Evolution of cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis: are there treatment alternatives? Am. J. Surg. 2011 Feb;201(2):157-9.

- Esquivel J, Lowy AM, Markman M, Chua T, Pelz J, Baratti D, Baumgartner JM, Berri R, Bretcha-Boix P, Deraco M, Flores-Ayala G, Glehen O, Gomez-Portilla A, González-Moreno S, Goodman M, Halkia E, Kusamura S, Moller M, Passot G, Pocard M, Salti G, Sardi A, Senthil M, Spilioitis J, Torres-Melero J, Turaga K, Trout R. The American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies (ASPSM) Multiinstitution Evaluation of the Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score (PSDSS) in 1,013 Patients with Colorectal Cancer with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014 Dec;21(13):4195-201.

- Sugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2003 Jul;12(3):703-27, xiii.

- Byrne RM, Gilbert EW, Dewey EN, Herzig DO, Lu KC, Billingsley KG, Deveney KE, Tsikitis VL. Who Undergoes Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Appendiceal Cancer? An Analysis of the National Cancer Database. J. Surg. Res. 2019 Jun;238:198-206.

- Elias D, David A, Sourrouille I, Honoré C, Goéré D, Dumont F, Stoclin A, Baudin E. Neuroendocrine carcinomas: optimal surgery of peritoneal metastases (and associated intra-abdominal metastases). Surgery. 2014 Jan;155(1):5-12.

- Grass F, Vuagniaux A, Teixeira-Farinha H, Lehmann K, Demartines N, Hübner M. Systematic review of pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced peritoneal carcinomatosis. Br J Surg. 2017 May;104(6):669-678.

- Hübner M, Teixeira H, Boussaha T, Cachemaille M, Lehmann K, Demartines N. [PIPAC–Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy. A novel treatment for peritoneal carcinomatosis]. Rev Med Suisse. 2015 Jun 17;11(479):1325-30.