Pharyngitis

Pharyngitis means sore throat, which is the inflammation of the mucous membranes of the oropharynx (the back of the throat) 1. A pharyngitis (sore throat) in most cases can be caused by a virus or a bacterial infection. Other less common causes of pharyngitis include allergies, trauma, cancer, acid reflux (laryngopharyngeal reflux) and certain toxins 2. Your throat is a tube that carries food to your esophagus and air to your windpipe and larynx (also called the voice box). The technical name for the throat is pharynx.

You can have a pharyngitis (sore throat) for many reasons. Often, colds and flu cause sore throats. Other causes can include:

- Allergies —You may also be allergic to pollens, molds, animal dander, and/or house dust, for examples, which can lead to a sore throat.

- Mononucleosis — Mononucleosis has the longest duration of symptoms, such as sore throat and extreme fatigue, and can last several weeks. Other symptoms include swollen glands in the neck, armpits, and groin; fever, chills, headache, or sometimes, serious breathing difficulties.

- Irritation—Dry heat, dehydration, chronic stuffy nose, pollutants, car exhaust, chemical exposure, or straining your voice are examples of irritations that can lead to a sore throat.

- Smoking

- Strep throat — Strep throat is an infection caused by Streptococcus pyogenes also known as Group A Streptococcus bacteria. This infection can also cause scarlet fever, tonsillitis, pneumonia, sinusitis, and ear infections. Symptoms of strep throat often include fever (greater than 101°F or 38.3 °C), white draining patches on the throat, and swollen or tender lymph glands in the neck. Children may have a headache and stomach pain.

- Tonsillitis — Tonsillitis refers to inflammation of the pharyngeal tonsils, which are lymph glands located in the back of the throat that are visible through the mouth. Typically, tonsillitis happens suddenly (acute). Some patients experience recurrent acute episodes of tonsillitis, while others develop persistent (chronic) tonsillitis.

- Reflux—Reflux occurs when you regurgitate stomach contents up into the throat. You may notice this often in the morning when you first wake up.

- Tumors—Tumors of the throat, tongue, and larynx (voice box) can cause a sore throat with pain going up to the ear. Other important symptoms can include hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, noisy breathing, a lump in the neck, unexplained weight loss, and/or spitting up blood in the saliva or phlegm.

- Epiglottitis—Epiglottitis is the most dangerous throat infection, because it causes swelling that closes the airway and requires prompt emergency medical attention. Suspect it when swallowing is extremely painful (causing drooling), when speech is muffled, and when breathing becomes difficult. Epiglottitis is often not seen just by looking in your mouth.

Treatment depends on the cause. Antibiotics cannot be used to treat a virus. Sucking on lozenges, drinking lots of liquids, and gargling may ease the pain. Over-the-counter pain relievers can also help, but children should not take aspirin.

A mild sore throat associated with cold or flu symptoms can be made more comfortable with the following remedies:

- Increase your liquid intake.

- Drink warm tea with lemon and honey (a favorite home remedy).

- Use a personal steamer or place a humidifier in your bedroom.

- Gargle with warm salt water several times daily: ¼ tsp salt to ½ cup water.

- Take over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol Sore Throat®, Tempra®) or ibuprofen (Motrin IB®, Advil®).

For a more severe sore throat, your doctor may want to do a throat culture—swabbing the inside of your throat to see if there is a bacterial infection. If it is negative, your physician will base their treatment recommendation on the severity of your symptoms and the appearance of your throat on examination.

If you have a bacterial infection your doctor will likely recommend an antibiotic (such as penicillin or erythromycin) that kills or impairs bacteria. Antibiotics do not cure viral infections, but viruses do lower the patient’s resistance to bacterial infections. When a combined infection like this happens, antibiotics may be recommended.

It is important to take an antibiotic as your physician directs and to finish all doses, even if your symptoms improve, otherwise the infection may not be gone and could return. Some patients will experience returning infections despite antibiotic treatment. If you experience this, it is important to discuss this situation with your physician.

Acute pharyngitis

Acute pharyngitis is defined as an infection of the pharynx and/or tonsils 3. Acute pharyngitis is a very common pathology among children and adolescents. Although viruses cause most acute pharyngitis episodes, group A Streptococcus (group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus) also known as Streptococcus pyogenes causes 37% of cases of acute pharyngitis in children older than 5 years 4 and accounts for 5% to 15% of all adult cases of acute pharyngitis 5. Other bacterial causes of pharyngitis are Group C Streptococcus (5% of total cases), Chlamydia pneumoniae (1%), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (1%) and anaerobic species (1%) 3. Between viruses Rhinovirus, Coronavirus and Adenovirus account for the 30% of the total cases, Epstein Barr virus for 1%, Influenza and Parainfluenza virus for about 4% 6.

Streptococcal pharyngitis has a peak incidence in the early school years and it is uncommon before 3 years of age. Illness occurs most often in winter and spring 7. The infection is transmitted via respiratory secretions and the incubation period is 2-5 days. Communicability of the infection (contagiousness) is highest during acute phase and in untreated people gradually diminishes over a period of weeks; it ceases after 24 hours of antibiotic therapy 8.

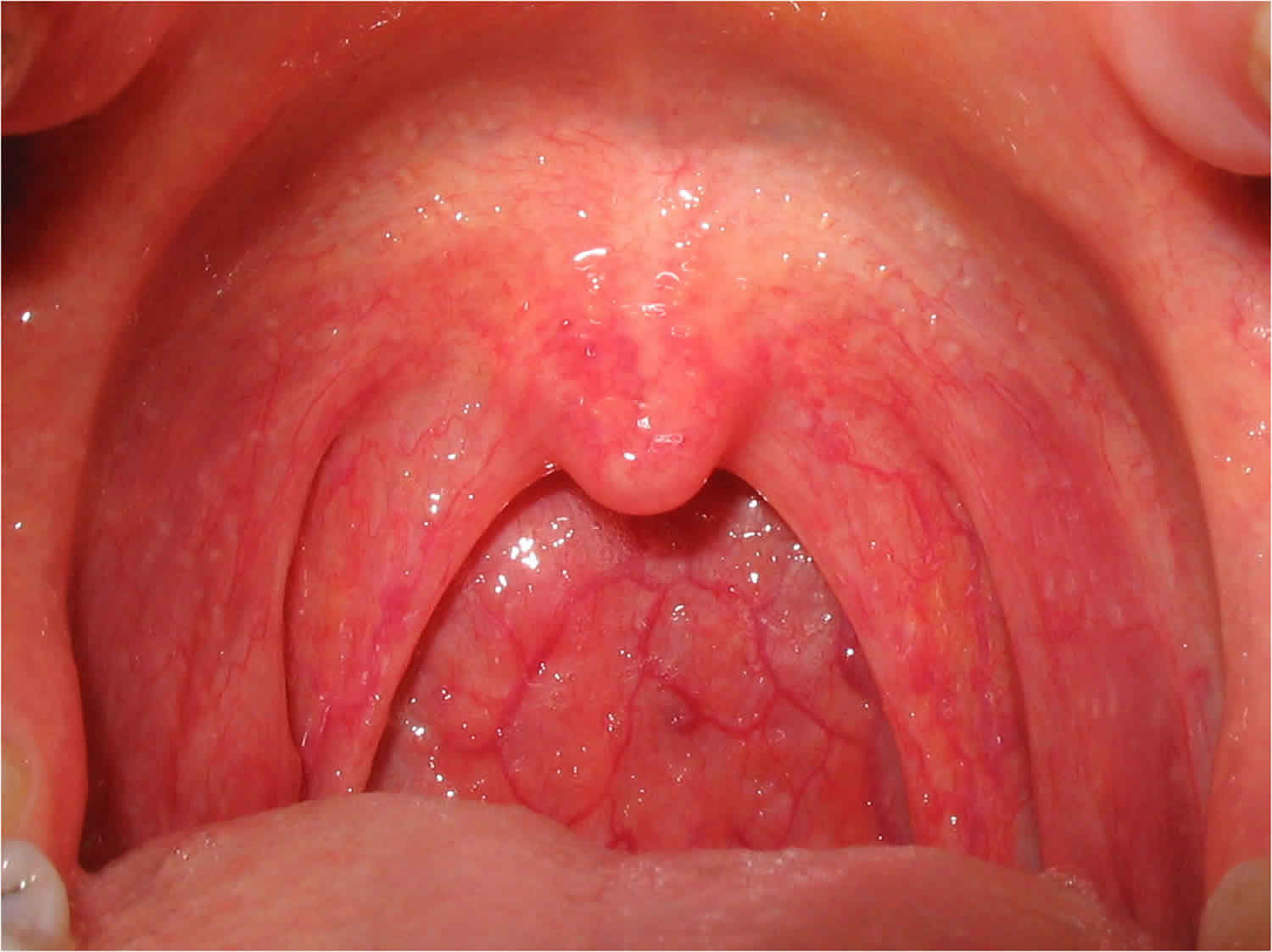

Clinical manifestations include sore throat and fever with sudden onset, red pharynx, enlarged tonsils covered with a yellow, blood-tinged exudate. There may be petechiae on the soft palate and posterior pharynx. The anterior cervical nodes are enlarged and swollen. Headache and gastrointestinal symptoms (vomiting and abdominal pain) are frequent. Table 1 below shows signs and symptoms of strep pharyngitis (group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus) and their sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis 9.

Chronic pharyngitis

Chronic pharyngitis is a chronic inflammation of the pharyngeal mucosa, submucosa, and lymphoid tissues 10. According to pathology, chronic pharyngitis is divided into simple catarrhal pharyngitis and hypertrophic pharyngitis 11. Chronic pharyngitis is an inflammation of the upper respiratory tract, which is stubborn and difficult to cure. Symptoms of chronic pharyngitis vary from person to person. Usually, the pharynx has various discomforts, such as foreign body sensation, burning sensation, and language disorder 12. The cause of chronic pharyngitis is complex. Bacterial infection is the most important cause, followed by non-infectious factors, such as obstructive sleep apnea and hypopnea syndrome, and occupational exposure. The pathogenesis of chronic pharyngitis mainly includes neurophysiological mechanisms and the L-form mechanism 13.

Diseases similar to chronic pharyngitis are difficult to diagnose at present. They are easy to be misdiagnosed with some diseases such as chronic tonsillitis, chronic laryngitis, pharyngeal and laryngeal tumors, and cervical spondylosis 14. The current early diagnosis of chronic pharyngitis mainly relies on the doctor’s clinical experience to ask the patient’s medical history to reach a conclusion, and the positive predictive value based on the doctor’s clinical experience diagnosis is only 75% 15. Computed tomography (CT scan) can improve the accuracy rate of early diagnosis of most diseases, but due to the high cost of computed tomography, it is impractical for the diagnosis of chronic pharyngitis. In order to reduce costs and avoid misdiagnosis, the search for an affordable and rapid diagnostic method is becoming more and more important for chronic pharyngitis research.

Speech disorder and audio frequency reduction are typical symptoms of chronic pharyngitis. Most patients with chronic pharyngitis have symptoms of speech disorder and audio reduction 16. For chronic pharyngitis, it is easy to miss the best treatment time because there are no biological indicators for diagnosis in the early stage, the diagnosis cost is high, and there are limitations in the operation, so the probability of misdiagnosis is greatly increased, leading to the gradual increase of potential patients with chronic pharyngitis 17. In recent years, the diagnosis of chronic pharyngitis based on speech disorder has gradually become a hot spot of extensive research 18. Research shows that with the continuous progress of machine learning technology, it is feasible to diagnose chronic pharyngitis by using machine learning through speech disorder. The diagnosis based on speech disorder can transmit vocalization through a microphone and analyze the voice signal, so as to get a preliminary diagnosis for patients. Compared to other methods, this diagnostic method is simple and inexpensive.

Streptococcal pharyngitis

Streptococcus pyogenes also known as Group A Streptococcus (a facultative Gram-positive coccus that grows in chains), is the most common bacterial cause for acute pharyngitis and accounts for 5% to 15% of all adult cases and 20% to 30% of all pediatric cases 19. Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus) is the most common bacterial cause of pharyngitis in children and adolescents with a peak incidence in winter and early spring 20. Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus) pharyngitis is also more common in school-aged children or in those with a direct relation to school-aged children. A recent meta-analysis showed that the prevalence Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus) pharyngitis in those less than 18 years old who present to an outpatient center for treatment for a sore throat was 37%, and for children younger than 5, it was 24% 21. In adults, however, Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus) pharyngitis will typically occur before the age of 40 and decline steadily after that 22.

The modified Centor criteria (see below under streptococcal pharyngitis diagnosis) is a clinical aid for physicians to determine who to test and treat when Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis is suspected. However, the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) currently notes that the signs and symptoms of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis overlap too broadly with other infectious and non-infectious causes to allow for a precise diagnosis to be made based upon history and physical alone.

The broad overlap of signs and symptoms seen in bacterial and viral pharyngitis coupled with the inaccuracy of medical providers when distinguishing Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis from other causes, the Infectious Disease Society of America recommends confirmatory bacterial testing in all cases except when a clear viral etiology is expected. Diagnostic testing in children younger than 3 is not recommended because both Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis and acute rheumatic fever is rare in this age group. However, children under 3 years of age with risk factors, including but not limited to siblings with Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis, may be considered for testing 19.

For those who undergo testing, the Infectious Disease Society of America recommends that a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) be employed as the first-line measure to aid the physician in the diagnosis of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis. Positive tests do not need to be backed up by a throat culture in all age groups due to the highly specific nature of the rapid antigen detection test. In children, a negative rapid antigen detection test (RADT) should be followed by a throat culture, but this is not needed in adults due to both the low incidence of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis and acute rheumatic fever seen in this population. Anti-streptococcal antibody titers are not recommended to aid the physician in the acute diagnosis of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis because the test reflects previous infections. Following treatment, a test of cure is not needed but may be considered in special circumstances 19.

Figure 1. Streptococcal pharyngitis

Streptococcal pharyngitis symptoms

Multiple studies have shown that history and physical examination alone fail to aid the physician in accurately diagnosing Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus) pharyngitis in patients 23. However, a history that consists of a sore throat, abrupt onset of fever, the absence of a cough, and exposure to someone with Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis within the previous 2 weeks may be suggestive of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis 24. Physical exam findings including cervical lymphadenopathy, pharyngeal inflammation, and tonsillar exudate. Palatine petechiae and uvular edema are also suggestive 25.

Table 1. Clinical signs and symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis, their sensitivity and specificity

| Symptoms and Clinical Findings | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Absence of cough | 51-79 | 36-68 |

| Anterior cervical nodes swollen or enlarged | 55-82 | 34-73 |

| Headache | 48 | 50-80 |

| Myalgia | 49 | 60 |

| Palatine petechiae | 7 | 95 |

| Pharyngeal exudates | 26 | 88 |

| Fever >38°C | 22-58 | 52-92 |

| Tonsillar exudate | 36 | 85 |

Streptococcal pharyngitis complications

Complications of the streptococcal pharyngitis infection can be distinguished in suppurative and nonsuppurative.

- Suppurative complications seen with Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis is due to the spread of Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus) to adjacent tissues, include cervical lymphadenitis, peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess, otitis media, mastoiditis, necrotizing fasciitis, bacteremia, meningitis, brain abscess, and jugular vein septic thrombophlebitis and sinusitis. The use of antibiotics have reduced the incidence of this group of complications, that remain a reality when primary illness has gone unnoticed or untreated 7.

- Non suppurative complications of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis, immune-mediated complications are acute rheumatic fever, acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, scarlet fever, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, Sydenham chorea, post-streptococcal reactive arthritis and Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcus pyogenes (PANDAS).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), at least 15.6 million people have rheumatic heart disease, and 233,000 deaths annually are directly attributable to acute rheumatic fever. Due to the limitations of reports related to limited resources in developing countries, it is likely that the prevalence and incidence of acute rheumatic fever are largely underestimated 26.

The prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in children aged 5-14 years is higher in sub-Saharan Africa (5.7 per 1000), in Indigenous populations of Australia and New Zealand (3.5 per 1000), and southcentral Asia (2.2 per 1000), and lower in developed countries (usually 0.5 per 1000) 27.

A systematic review of 10 population-based studies from 10 countries on all continents, except Africa, published from 1967 to 1996, describes the worldwide incidence of acute rheumatic fever. The overall mean incidence rate of first attack of acute rheumatic fever was 5-51/100,000 population (mean 19/100,000). A low incidence rate of ≤10/100,000 per year was found in America and Western Europe, while a higher incidence (> 10/100,000) was documented in Eastern Europe, Middle East (highest), Asia and Australasia. Studies with longitudinal data displayed a falling incidence rate over time 28.

In the United States, the number of acute rheumatic fever cases has fallen dramatically over the last half century. A national study conducted in 2000 detailing the characteristics of American pediatric patients hospitalized with acute rheumatic fever found that the incidence was 14.8 cases per 100,000 hospitalized children (though the true national incidence of acute rheumatic fever cases is 1 case per 100,000 population) 29.

Streptococcal pharyngitis diagnosis

A variety of clinical decision rules have been developed to improve the diagnosis of Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis and to guide testing and treatment. The Centor Score is one of the most commonly used, particularly for adult patients 30.

Centor Criteria (1 point for each) for Group A Beta-hemolytic Streptococci 31:

- Tonsillar exudate or swelling

- Swollen and tender anterior cervical nodes

- History of fever (temperature > 101 °F or 38°C)

- Absence of a cough

- Age 3 to 14 years

More likely in 5 to 15 years of age and not valid under 3 years old.

Point Totals and Recommended Actions:

- 0-1: No testing or antibiotics.

- 2-3: Rapid antigen test.

- 4: No testing, empiric antibiotics.

White blood cell counts have minimal value in the differentiation of viral versus bacterial etiologies of pharyngitis. A lymphocytosis (greater than 50%) or increased atypical lymphocytes (greater than 10%) may suggest infectious mononucleosis.

Rapid antigen detection tests (RADT) are very specific for Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, but their sensitivity varies widely, from about 70% to 90%. If the test is positive, treatment should be initiated. If it is negative, particularly in children, a throat culture should be obtained and should guide treatment.

Throat cultures have been the ideal standard for diagnosis, but their sensitivity is variable and is influenced by many factors. These factors include the bacterial burden, site of collection (the tonsillar surface is best), culture medium, and culture atmosphere.

A heterophile antibody, or Monospot, test is 70% to 92% sensitive and 96% to 100% specific. This test for infectious mononucleosis is commonly available, but the ideal standard is to use Epstein-Barr virus serology. The test’s sensitivity is lessened by testing early in the course of the illness (1 to 2 weeks) and by the age of the patient (less than 12 years).

For gonococcal origin, use a culture. Thayer-Martin agar is most commonly used. For Candida, test with a potassium hydroxide preparation or Sabouraud agar.

A chest X-ray is not needed for routine cases. If airway compromise is suspected, a lateral neck X-ray should be obtained.

A CT scan may help identify a peritonsillar abscess.

Streptococcal pharyngitis treatment

The main goals of treatment for Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis include reducing a patient’s duration and severity of symptoms, preventing acute and delayed complications, and the preventing the spread of infection to others.

Those with Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis should be treated with either penicillin or amoxicillin given their relatively low cost and low adverse effect profile. Penicillin can be prescribed as either 250 mg twice or three times daily for children and 250 mg 4 times daily for adults. If either the clinician or patient prefers an intramuscular approach for penicillin treatment, then benzathine penicillin G, can be given as a one-time dose of 600,000 units if the patient is less than 27 kg and 1.2 million U if the patient is greater than or equal to 27 kg. If amoxicillin is chosen by the prescriber, then the medication can be given 50 mg/kg, once daily with a maximum of 1000 mg per dose or 25 mg/kg twice a day with a maximum of 500 mg per dose. With either the penicillin or oral amoxicillin route, a total of 10 days of treatment should be completed 19.

For those with an allergy to penicillin, clindamycin (7 mg/kg/dose, 3 times daily; max = 300 mg/dose; 10 day duration), clarithromycin (7.5 mg/kg/dose. twice daily; max = 250mg/dose; 10 day duration) or azithromycin (12 mg/kg, once daily; max = 500mg/dose; 5 day duration) can be prescribed. A first-generation cephalosporin (cephalexin 20 mg/kg/dose, twice daily, max = 500mg/dose; duration 10 days) can also be used for those patients without an anaphylactoid reaction to penicillin 19.

As adjunctive therapy for the patient with Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis, the Infectious Disease Society of America recommends acetaminophen or an NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) to control pain associated with the disease or any fever that should develop. Currently, the Infectious Disease Society of America does not recommend routine adjunctive therapy with corticosteroids for those with Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis 19.

Following antibiotic treatment, patients may see the resolution of symptoms within one to 3 days and may return to work or school after 24 hours of treatment. A test of cure is not recommended after a course of treatment unless a patient has a history of acute rheumatic fever or another Streptococcus pyogenes complication. Likewise, post-exposure prophylaxis is not recommended unless a patient has a history of acute rheumatic fever, during outbreaks of non-supportive complications, or when Streptococcus pyogenes infections are seen recurrently in households or close contacts. Prevention of the disease is through proper hand hygiene, and it also is key to halting disease progression within close quarters 19.

Pharyngitis causes

About 50% to 80% of pharyngitis or sore throat symptoms, are viral in origin and include a variety of viral pathogens. These pathogens are predominantly rhinovirus, influenza, adenovirus, coronavirus, and parainfluenza. Less common viral pathogens include herpes, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and coxsackievirus. More severe cases tend to be bacterial and may develop after an initial viral infection.

Less than 1 in 3 sore throats is caused by a bacterial infection. The most common bacterial infection is Strepococcus pyogenes which is a group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, sometimes called a ‘strep’ throat.

Some sore throats are caused by the bacteria Strepococcus pyogenes. This is . If bacteria are the cause, you tend to become very unwell and your infection seems to get much worse. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci cause 5% to 36% of cases of acute pharyngitis. Other bacterial causes include Group B and C streptococci, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Candida, Neisseria meningitidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, Fusobacterium necrophorum, and Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Environmental allergies and chemical exposures may also cause acute pharyngitis. If the sore throat is caused by bacteria, you may benefit from antibiotics.

Pharyngitis symptoms may also be part of the symptom complexes of other serious illnesses, including peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, and Kawasaki disease 32.

Pharyngitis prevention

Here are some tips on how you can to avoid developing a sore throat:

- Avoid smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke. Tobacco smoke, whether primary or secondary, contains hundreds of toxic chemicals that can irritate the throat lining.

- If you have seasonal allergies or ongoing allergic reactions to dust, molds, or pet dander, you’re more likely to develop a sore throat than people who don’t have allergies. Treatment of seasonal or environmental allergies can decrease this risk.

- Avoid exposure to chemical irritants. Particles in the air from the burning of fossil fuels, as well as common household chemicals, can cause throat irritation. Wearing a mask may be helpful to decrease exposure, in certain situations.

- If you experience frequent sinus infections or have chronic post nasal drip, drainage from your nose or sinuses can cause throat irritation as well. Rinsing the nose with salt water may help decrease this drainage.

- If you live or work in close quarters such as a child care center, classroom, office, dormitory, prison, or military installation, you may be at greater risk of sore throat because viral and bacterial infections spread easily in environments where people are in close proximity. Minimizing contact with persons who are, or may be, sick and washing your hands frequently can help prevent the spread of infection.

- Maintain good hygiene. Do not share napkins, towels, and utensils with an infected person. Wash your hands regularly with soap or a sanitizing gel for at least 10 – 15 seconds.

- If you have reduced immunity (from HIV or diabetes, steroid treatment or chemotherapy, a poor diet, or extreme fatigue, for examples), you may be more susceptible to infections in general.

Pharyngitis symptoms

If your pharyngitis (sore throat) is caused by a cold (viral pharyngitis), you may also have a runny nose (rhinorrhea), cough, possibly fever, diarrhea, hoarseness and feel very tired.

If it’s a strep pharyngitis (bacterial pharyngitis), other symptoms may include:

- swollen glands in the neck

- swollen red tonsils

- rash

- fever

- tummy pain

- vomiting

Anyway the clinical presentations of streptococcal pharyngitis and viral pharyngitis show considerable overlap and no single element of the patient’s history or physical examination reliably confirms or excludes streptococcal pharyngitis 9.

If you or child has a sore throat and you are worried about the symptoms, see your doctor. Seek medical attention if you have:

- Trouble breathing or swallowing

- A stiff or swollen neck

- A high fever (over 101°F or 38.3 °C)

- Severe and prolonged sore throat

- Difficulty opening the mouth

- Swelling of the face or neck

- Joint pain

- Earache

- Rash

- Blood in saliva or phlegm

- Frequently recurring sore throat

- Lump in neck

- Hoarseness lasting over two weeks

Epiglottitis is the most dangerous throat infection, because it causes swelling that closes the airway and requires prompt emergency medical attention. Suspect it when swallowing is extremely painful (causing drooling), when speech is muffled, and when breathing becomes difficult. Epiglottitis is often not seen just by looking in your mouth.

Pharyngitis diagnosis

Your or your child’s health care provider will start with a physical exam that will include:

- Using a lighted instrument to look at the throat, and likely the ears and nasal passages

- Gently feeling (palpating) the neck to check for swollen glands (lymph nodes)

- Listening to your or your child’s breathing with a stethoscope

- Your or your child’s health care provider may take a swab from the throat to see if you have a bacterial infection.

Throat swab

In many cases, doctors use a simple test to detect streptococcal bacteria, the cause of strep throat. The doctor rubs a sterile swab over the back of the throat to get a sample of secretions and sends the sample to a lab for testing. Many clinics are equipped with a lab that can get a test result for a rapid antigen test within a few minutes. However, a second, often more reliable test, called a throat culture, is sometimes sent to a lab that returns results within 24 to 48 hours.

Rapid antigen detection tests (RADT) aren’t as sensitive, although they can detect Strep bacteria quickly. Because of this, the doctor may send a throat culture to a lab to test for strep throat if the antigen test comes back negative.

In some cases, doctors may use a molecular test to detect streptococcal bacteria. In this test, a doctor swipes a sterile swab over the back of the throat to get a sample of secretions. The sample is tested in a lab. Your or your child’s doctor may have accurate results within a few minutes.

Pharyngitis treatment

There is no way to cure a sore throat that is caused by a virus. A pharyngitis caused by a viral infection usually lasts five to seven days and doesn’t require medical treatment. You can just treat the symptoms with pain relief, many people turn to acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) or other mild pain relievers. Consider giving your child over-the-counter pain medications designed for infants or children, such as acetaminophen (Children’s Tylenol, FeverAll, others) or ibuprofen (Children’s Advil, Children’s Motrin, others), to ease symptoms. The sore throat should clear up in 5 to 7 days.

Never give aspirin to children or teenagers because it has been linked to Reye’s syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that causes swelling in the liver and brain.

If the pharyngitis (sore throat) is caused by bacteria, you may benefit from antibiotics.

If a sore throat is a symptom of a condition other than a viral or bacterial infection, other treatments will likely be considered depending on the diagnosis.

Treating bacterial pharyngitis

If your or your child’s sore throat is caused by a bacterial infection, your doctor or pediatrician will prescribe antibiotics.

You or your child must take the full course of antibiotics as prescribed even if the symptoms are gone. Failure to take all of the medication as directed can result in the infection worsening or spreading to other parts of the body.

Not completing the full course of antibiotics to treat strep throat can increase a child’s risk of rheumatic fever or serious kidney inflammation.

Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about what to do if you forget a dose.

Pharyngitis home remedy

Regardless of the cause of your sore throat, these at-home care strategies can help you ease your or your child’s symptoms. Along with being sore, your throat may also be scratchy and you may have difficulty swallowing. To help with the symptoms, try gargling with warm, salty water or drinking hot water with honey and lemon. Warm or iced drinks and ice blocks may be soothing.

- Gargle with saltwater. A saltwater gargle of 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon (1.25 to 2.50 milliliters) of table salt to 4 to 8 ounces (120 to 240 milliliters) of warm water can help soothe a sore throat. Children older than 6 and adults can gargle the solution and then spit it out.

Avoid foods that cause pain when you swallow. Try eating soft foods such as yogurt, soup or ice cream.

It is important to stay well hydrated so drink plenty of water. If you have an existing medical condition, check with your doctor about how much water is right for you. Avoid caffeine and alcohol, which can dehydrate you.

Keep the room at a comfortable temperature and rest and avoid heavy activity until symptoms go away.

- Humidify the air. Use a cool-air humidifier to eliminate dry air that may further irritate a sore throat, being sure to clean the humidifier regularly so it doesn’t grow mold or bacteria. Or sit for several minutes in a steamy bathroom.

Smoking or breathing in other people’s smoke can make symptoms worse. Try to avoid being around people who are smoking. If you are a smoker, try to cut down or quit. For advice on quitting smoking, visit the Quit Now website.

See your doctor if:

- your sore throat becomes worse

- your sore throat does not improve after 5 days

- you are concerned

- Wolford RW, Schaefer TJ. Pharyngitis. [Updated 2019 Feb 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519550

- Frost HM, McLean HQ, Chow BDW. Variability in Antibiotic Prescribing for Upper Respiratory Illnesses by Provider Specialty. J. Pediatr. 2018 Dec;203:76-85.e8.

- Regoli M, Chiappini E, Bonsignori F, Galli L, de Martino M. Update on the management of acute pharyngitis in children. Ital J Pediatr. 2011;37:10. Published 2011 Jan 31. doi:10.1186/1824-7288-37-10 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3042010

- Shaikh N, Leonard E, Martin JM. Prevalence of Streptococcal Pharyngitis and Streptococcal Carriage in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e557–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2648. Epub 2010.

- Ashurst JV, Edgerley-Gibb L. Streptococcal Pharyngitis. [Updated 2019 Mar 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525997

- Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:205–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440308

- Gerber MA. Nelson, Textbook of pediatrics, International editions. 18. Vol. 182. 2007. Group A Streptococcus; pp. 1135–39.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27. Elk. Grove Village; 2006.

- Choby BA. Diagnosis and treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:383–90.

- Li Z, Huang J, Hu Z. Screening and Diagnosis of Chronic Pharyngitis Based on Deep Learning. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1688. Published 2019 May 14. doi:10.3390/ijerph16101688 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6572379

- Kumari J.O., Rajendran R. Effect of topical nasal steroid spray in the treatment of non-specific recurrent/chronic pharyngitis—A trial study. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008;60:199–201. doi: 10.1007/s12070-008-0076-z

- Murray R.C., Chennupati S.K. Chronic streptococcal and non-streptococcal pharyngitis. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets (Former. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord.) 2012;12:281–285. doi: 10.2174/187152612801319311

- Badran H., Salah M., Fawzy M., Sayed A., Ghaith D. Detection of bacterial biofilms in chronic pharyngitis resistant to medical treatment. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2015;124:567–571. doi: 10.1177/0003489415570934

- Zhang Z. Epidemiological investigation methods and problems of neurological diseases. Chin. J. Neurol. 2005;38:65–66.

- Schrag A., Horsfall L., Walters K., Noyce A., Petersen I. Prediagnostic presentations of Parkinson’s disease in primary care: A case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:57–64. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70287-X

- Tsanas A., Little M.A., McSharry P.E., Spielman J., Ramig L.O. Novel speech signal processing algorithms for high-accuracy classification of Parkinson’s disease. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2012;59:1264–1271. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2183367

- Little M.A., McSharry P.E., Roberts S.J., Costello D.A., Moroz I.M. Exploiting nonlinear recurrence and fractal scaling properties for voice disorder detection. Biomed. Eng. Online. 2007;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-6-23

- Tsanas A., Little M.A., Fox C., Ramig L.O. Objective automatic assessment of rehabilitative speech treatment in Parkinson’s disease. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2014;22:181–190. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2013.2293575

- Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, Martin JM, Van Beneden C. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):1279-82.

- Danchin MH, Rogers S, Kelpie L, Selvaraj G, Curtis N, Carlin JB, Nolan TM, Carapetis JR. Burden of acute sore throat and group A streptococcal pharyngitis in school-aged children and their families in Australia. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):950-7.

- Shaikh N, Leonard E, Martin JM. Prevalence of streptococcal pharyngitis and streptococcal carriage in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2010 Sep;126(3):e557-64.

- André M, Odenholt I, Schwan A, Axelsson I, Eriksson M, Hoffman M, Mölstad S, Runehagen A, Lundborg CS, Wahlström R., Swedish Study Group on Antibiotic Use. Upper respiratory tract infections in general practice: diagnosis, antibiotic prescribing, duration of symptoms and use of diagnostic tests. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;34(12):880-6.

- Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, Martin JM, Van Beneden C., Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):e86-102.

- Choby BA. Diagnosis and treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Mar 01;79(5):383-90.

- Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, Ives K, Carey M. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA. 2000 Dec 13;284(22):2912-8.

- Carapetis JR. WHO/FCH/CAH/05·07. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. The current evidence for the burden of group A streptococcal diseases; pp. 1–57. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69063/WHO_FCH_CAH_05.07.pdf

- Carapetis JR, McDonald M, Wilson NJ. Acute rheumatic fever. Lancet. 2005;366:155–68. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66874-2.

- Tibazarwa KB, Volmink JA, Mayosi BM. Incidence of acute rheumatic fever in the world: a systematic review of population-based studies. Heart. 2008;94:1534–40. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.141309.

- Miyake CY, Gauvreau K, Tani LY, Sundel RP, Newburger JW. Characteristics of children discharged from hospitals in the United States in 2000 with the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever. Pediatrics. 2007;120:503–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3606.

- Akhtar M, Van Heukelom PG, Ahmed A, Tranter RD, White E, Shekem N, Walz D, Fairfield C, Vakkalanka JP, Mohr NM. Telemedicine Physical Examination Utilizing a Consumer Device Demonstrates Poor Concordance with In-Person Physical Examination in Emergency Department Patients with Sore Throat: A Prospective Blinded Study. Telemed J E Health. 2018 Oct;24(10):790-796.

- McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, Low DE. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with sore throat. CMAJ. 1998;158(1):75–83.

- Gottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical Mimics: An Emergency Medicine-Focused Review of Streptococcal Pharyngitis Mimics. J Emerg Med. 2018 May;54(5):619-629.