Presbycusis

Presbycusis is a medical term for age-related hearing loss, specifically a sensorineural hearing loss in elderly individuals, typically begins with the loss of higher frequencies, so that certain speech sounds (such as ‘p’, ‘f’ and ‘t’) end up sounding very similar. Presbycusis or age-related hearing loss is the loss of hearing that gradually occurs in most of people as they grow older. Presbycusis is one of the most common conditions affecting older and elderly adults.

Approximately one in three people in the United States between the ages of 65 and 74 has hearing loss, and nearly half of those older than 75 have difficulty hearing. According to the 2014 National Health Interview Survey, 43.2% of American adults above age 70 years reported having hearing trouble, compared with 5.5% of adults aged 18-39 years and 19.0% of adults aged 40-69 years 1. Having trouble hearing can make it hard to understand and follow a doctor’s advice, respond to warnings, and hear phones, doorbells, and smoke alarms. Hearing loss can also make it hard to enjoy talking with family and friends, leading to feelings of isolation.

Presbycusis (age-related hearing loss) most often occurs in both ears, affecting them equally. Because the loss is gradual, if you have age-related hearing loss you may not realize that you’ve lost some of your ability to hear.

There are many causes of age-related hearing loss. Most commonly, it arises from changes in the inner ear as you age, but it can also result from changes in the middle ear, or from complex changes along the nerve pathways from the ear to the brain. Certain medical conditions and medications may also play a role.

How do you hear?

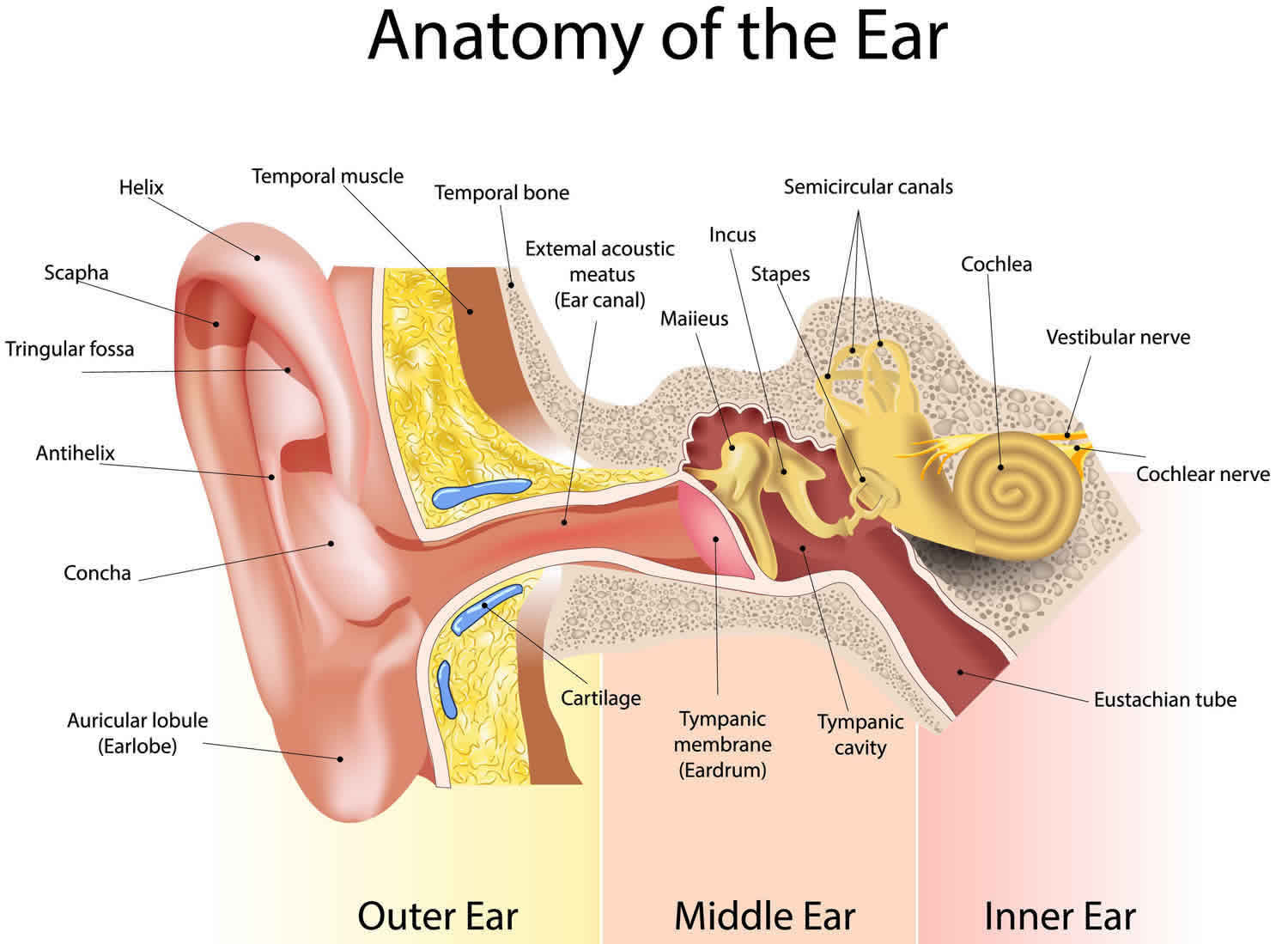

Hearing depends on a series of events that change sound waves in the air into electrical signals. Your auditory nerve then carries these signals to your brain through a complex series of steps.

- Sound waves enter the outer ear and travel through a narrow passageway called the ear canal, which leads to the eardrum (tympanic membrane).

- The eardrum (tympanic membrane) vibrates from the incoming sound waves and sends these vibrations to three tiny bones in the middle ear. These bones are called the malleus, incus, and stapes.

- The bones in the middle ear couple the sound vibrations from the air to fluid vibrations in the cochlea of the inner ear, which is shaped like a snail and filled with fluid. An elastic partition runs from the beginning to the end of the cochlea, splitting it into an upper and lower part. This partition is called the basilar membrane because it serves as the base, or ground floor, on which key hearing structures sit.

- Once the vibrations cause the fluid inside the cochlea to ripple, a traveling wave forms along the basilar membrane. Hair cells-sensory cells sitting on top of the basilar membrane-ride the wave.

- As the hair cells move up and down, microscopic hair-like projections (known as stereocilia) that perch on top of the hair cells bump against an overlying structure and bend. Bending causes pore-like channels, which are at the tips of the stereocilia, to open up. When that happens, chemicals rush into the cells, creating an electrical signal.

- The auditory nerve carries this electrical signal to the brain, which turns it into a sound that we recognize and understand.

Figure 1. Ear anatomy

Figure 2. Middle ear and auditory ossicles

Figure 3. Parts of the inner ear

Can I prevent presbycusis?

At this time, scientists don’t know how to prevent presbycusis (age-related hearing loss). However, you can protect yourself from noise-induced hearing loss by protecting your ears from sounds that are too loud and last too long. It is important to be aware of potential sources of damaging noises, such as loud music, firearms, snowmobiles, lawn mowers, and leaf blowers. Avoiding loud noises, reducing the amount of time you’re exposed to loud noise, and protecting your ears with ear plugs or ear muffs are easy things you can do to protect your hearing and limit the amount of hearing you might lose as you get older.

Presbycusis causes

The precise cause of presbycusis is currently not known, the cause of presbycusis is generally agreed to be multifactorial. Many factors can contribute to hearing loss as you get older. It can be difficult to distinguish presbycusis (age-related hearing loss) from hearing loss that can occur for other reasons, such as long-term exposure to noise.

Proposed causes of presbycusis include the following:

- Arteriosclerosis: Arteriosclerosis may cause diminished perfusion and oxygenation of the cochlea. Hypoperfusion leads to the formation of reactive oxygen metabolites and free radicals, which may damage inner ear structures directly as well as damage mitochondrial DNA of the inner ear. This damage may contribute to the development of presbycusis.

- Diet and metabolism

- Diabetes accelerates the process of atherosclerosis, which may interfere with perfusion and oxygenation of the cochlea.

- Diabetes causes diffuse proliferation and hypertrophy of the vascular intimal endothelium, which may also interfere with perfusion of the cochlea.

- In 2009, Kovacií et al 2 studied auditory brainstem function in elderly diabetic patients with presbycusis. Their data supported a hypothesis that brainstem neuropathy in diabetes mellitus can be assessed with auditory brainstem response, even in elderly patients with sensorineural hearing loss.

- Le and Keithley have demonstrated diets high in antioxidants such as vitamins C and E reduce the progression of presbycusis in a mouse model.

- Accumulated exposure to noise

- Drug and environmental chemical exposure

- Stress

- Genetics

- Genetic programming for early aging of parts of the auditory system may influence the development of presbycusis. Often, concomitant impairment of hearing, balance, sense of smell, taste, and visual acuity is associated with the aging process.

- Likewise, genetically programmed susceptibility to environmental factors (eg, noise, ototoxic drugs and chemicals, stress) may be involved.

Presbycusis is a diagnosis of exclusion that should not be made until all other possible causes of hearing loss in elderly individuals have been evaluated and excluded.

Causes as simple as cerumen impaction (impacted ear wax) and as complex as otosclerosis or cholesteatoma must not be overlooked in the elderly patient with hearing loss because these are amenable to treatment.

Noise-induced hearing loss is caused by long-term exposure to sounds that are either too loud or last too long. This kind of noise exposure can damage the sensory hair cells in your ear that allow you to hear. Once these hair cells are damaged, they do not grow back and your ability to hear is diminished.

Conditions that are more common in older people, such as high blood pressure or diabetes, can contribute to hearing loss. Medications that are toxic to the sensory cells in your ears (for example, some chemotherapy drugs) can also cause hearing loss.

Rarely, age-related hearing loss can be caused by abnormalities of the outer ear or middle ear. Such abnormalities may include reduced function of the tympanic membrane (the eardrum) or reduced function of the three tiny bones in the middle ear that carry sound waves from the tympanic membrane to the inner ear.

Most older people who experience hearing loss have a combination of both age-related hearing loss and noise-induced hearing loss.

Risk factors for presbycusis

The following factors contribute to presbycusis (age-related hearing loss):

- Family history (age-related hearing loss tends to run in families)

- Repeated exposure to loud noises

- Smoking (smokers are more likely to have such hearing loss than nonsmokers)

- Certain medical conditions, such as diabetes

- Certain medicines, such as chemotherapy drugs for cancer

Presbycusis symptoms

Presbycusis or age-related sensorineural hearing loss in elderly individuals, typically begins with the loss of higher frequencies, so that certain speech sounds (such as ‘p’, ‘f’ and ‘t’) end up sounding very similar. Presbycusis or age-related hearing loss is the loss of hearing that gradually occurs in most of people as they grow older. Presbycusis is one of the most common conditions affecting older and elderly adults.

The clinical presentation of presbycusis varies from patient to patient and is a result of the various combinations of cochlear and neural changes that have occurred. Patients typically may have more difficulty understanding rapidly spoken language, vocabulary that is less familiar or more complex, and speech within a noisy, distracting environment. In addition, localizing sound is increasingly difficult as the disease progresses.

For example, an elderly patient may be healthy and mentally alert. The patient’s only report may be a gradually progressive hearing loss with particular difficulty understanding words and conversation when a high level of ambient background noise is present. This may interfere with his effectiveness at meetings. He may have a history of noise exposure (eg, armed services, hunting, use of power tools, industrial occupation). A high-frequency sloping sensorineural hearing loss may be found. His speech discrimination score may be normal unless tested in the presence of background noise. Hearing aids with more gain in the higher frequencies to match his hearing loss may provide substantial benefit, depending on his needs and motivation. He may also be counseled to avoid excessive noise exposure.

Presbycusis (age-related hearing loss) symptoms may include:

- Difficulty hearing people around you

- Frequently asking people to repeat themselves

- Frustration at not being able to hear

- Certain sounds seeming overly loud

- Problems hearing in noisy areas

- Problems telling apart certain sounds, such as “s” or “th”

- More difficulty understanding people with higher-pitched voices

- Ringing in the ears

Talk to your health care provider if you have any of these symptoms. Symptoms of presbycusis may be like symptoms of other medical problems.

How can you tell if you have a hearing problem?

You can do a simple online hearing test on the Action on Hearing Loss website here (https://www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/hearing-health/check-your-hearing/).

This can tell you if you need to have a face-to-face hearing test.

Ask yourself the following questions. If you answer “yes” to three or more of these questions, you could have a hearing problem and may need to have your hearing checked 3:

- Do you sometimes feel embarrassed when you meet new people because you struggle to hear? YES / NO

- Do you feel frustrated when talking to members of your family because you have difficulty hearing them? YES / NO

- Do you have difficulty hearing or understanding co-workers, clients, or customers? YES / NO

- Do you feel restricted or limited by a hearing problem? YES / NO

- Do you have difficulty hearing when visiting friends, relatives, or neighbors? YES / NO

- Do you have trouble hearing in the movies or in the theater? YES / NO

- Does a hearing problem cause you to argue with family members? YES / NO

- Do you have trouble hearing the TV or radio at levels that are loud enough for others? YES / NO

- Do you feel that any difficulty with your hearing limits your personal or social life? YES / NO

- Do you have trouble hearing family or friends when you are together in a restaurant? YES / NO

Presbycusis diagnosis

Hearing problems can be serious. The most important thing you can do if you think you have a hearing problem is to seek advice from a health care provider. There are several types of professionals who can help you. You might want to start with your primary care physician, an otolaryngologist (ENT specialist), an audiologist, or a hearing aid specialist. Each has a different type of training and expertise. Each can be an important part of your hearing health care.

- An otolaryngologist is a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating diseases of the ear, nose, throat, and neck. An otolaryngologist, sometimes called an ENT, will try to find out why you’re having trouble hearing and offer treatment options. He or she may also refer you to another hearing professional, an audiologist.

- An audiologist has specialized training in identifying and measuring the type and degree of hearing loss. Some audiologists may be licensed to fit hearing aids.

- A hearing aid specialist is someone who is licensed by your state to conduct and evaluate basic hearing tests, offer counseling, and fit and test hearing aids.

A hearing test is also called audiometry, is a test to measure your ability to hear sounds. Sounds vary, based on their loudness (intensity or decibels [dB]) and the speed of sound wave vibrations (tone or frequency measured in cycles per second [Hertz]). Hearing occurs when sound waves stimulate the nerves of the inner ear. The sound then travels along nerve pathways to the brain. Sound waves can travel to the inner ear through the ear canal, eardrum, and bones of the middle ear (air conduction). They can also pass through the bones around and behind the ear (bone conduction).

There are several methods that can be used to test hearing, depending on your age, development, and health status.

Common adult hearing tests include:

| Test | What happens |

|---|---|

| Pure tone audiometry | you listen to different sounds through headphones and press a button or raise your hand each time you hear something |

| Speech perception test | similar to a pure tone audiometry test but you listen to speech rather than sounds |

| Tympanometry | a small device is placed in your ear to check for fluid behind your eardrum |

In adults and older children, several hearing tests may be done:

- Pure tone testing (audiogram) — For this test, you wear earphones attached to the audiometer. Pure tones are delivered to one ear at a time. You are asked to signal when you hear a sound. The minimum volume required to hear each tone is graphed. A device called a bone oscillator is placed against the mastoid bone to test bone conduction.

- Speech audiometry — This tests your ability to detect and repeat spoken words at different volumes heard through a head set.

- Immittance audiometry — This test measures the function of the ear drum and the flow of sound through the middle ear. A probe is inserted into the ear and air is pumped through it to change the pressure within the ear as tones are produced. A microphone monitors how well sound is conducted within the ear under different pressures.

- Tuning fork testing — To determine if there are any conductive or nerve issues, the audiologist uses a tuning fork to make a sound. The tuning fork is placed behind your ear or on your head. As it vibrates, you observe when the sound fades and if the sound is louder on one side or the other.

In a conventional audiometry (pure tone testing), usually you’ll listen through headphones to sounds of different tones and volumes and be asked to press a button or raise your hand each time you hear something. The noises will gradually become quieter to find the softest sounds that you can hear and the results recorded on a chart called on an audiogram.

You may also be given a headband with a vibrating pad. The pad sends sound through the bones in your head directly to the cochlea (hearing organ) in both your ears. Again, you’ll be asked to signal each time you hear a sound. This test checks whether the cochlea and/or the hearing nerve are working or damaged.

At some point, the audiologist may play a rushing noise into one ear to cover up sounds while they test the other ear.

The tests may vary and you may be asked to come back for more tests to find out more about your ears and hearing.

The INTENSITY of sound is measured in decibels (dB):

- A whisper is about 20 dB.

- Loud music (some concerts) is around 80 to 120 dB.

- A jet engine is about 140 to 180 dB.

Sounds greater than 85 dB can cause hearing loss after a few hours. Louder sounds can cause immediate pain, and hearing loss can develop in a very short time.

The TONE of sound is measured in cycles per second or Hertz:

- Low bass tones range around 50 to 60 Hz.

- Shrill, high-pitched tones range around 10,000 Hz or higher.

The normal range of human hearing is about 20 to 20,000 Hz. Human speech is usually 500 to 3,000 Hz.

Your hearing threshold levels (the quietest sounds you can hear) are measured in decibels (dB) at different frequencies from low (500 Hz) to high (8000 Hz).

In detailed audiometry, hearing is normal if you can hear tones from 250 to 8,000 Hz at 25 decibels (dB) or lower.

An audiogram is a chart used to plot out hearing sensitivity and visually display the results of an audiogram hearing test. The quietest sounds a person can hear—thresholds—are measured across a broad range of pitches.

The numbers on the top of the audiogram represent pitch. When reading them from left to right, pitch changes from low to high (bass to treble).

The numbers running down the side of the audiogram represent loudness level. When reading from top to bottom, the loudness changes from soft to loud.

The symbols on an audiogram represent the quietest sounds which a person can detect. Where the symbols fall on the audiogram indicate the degree of hearing loss (how much hearing loss is present in each ear) as well as the type of hearing loss (conductive, sensorineural, or mixed). Once the audiogram is completed, your audiologist will explain to you in depth your hearing sensitivity.

The following is a generic audiogram that displays pitch, loudness level, and the degrees of hearing loss.

Figure 4. Audiogram

Compare your hearing threshold levels to this scale:

Compare your hearing threshold levels to this scale:

- -10 (minus 10) – 25 dB Normal hearing

- 26 – 40 dB Mild hearing loss

- 41 – 55 dB Moderate hearing loss

- 56 – 70 dB Moderate/severe hearing loss

- 71 – 90 dB Severe hearing loss

- 91 – 100 dB Profound hearing loss

Normal Results

Normal results include:

- The ability to hear a whisper, normal speech, and a ticking watch is normal.

- The ability to hear a tuning fork through air and bone is normal.

- In detailed audiometry, hearing is normal if you can hear tones from 250 to 8,000 Hz at 25 dB or lower.

What abnormal results mean

There are many kinds and degrees of hearing loss. In some types, you only lose the ability to hear high or low tones, or you lose only air or bone conduction. The inability to hear pure tones below 25 dB indicates some hearing loss.

The amount and type of hearing loss may give clues to the cause, and chances of recovering your hearing.

The following conditions may affect your hearing test results:

- Acoustic neuroma

- Acoustic trauma from a very loud or intense blast sound

- Presbycusis (age-related hearing loss)

- Alport syndrome

- Chronic ear infections

- Labyrinthitis

- Ménière disease

- Ongoing exposure to loud noise, such as at work or from music

- Abnormal bone growth in the middle ear, called otosclerosis

- Ruptured or perforated eardrum

Other tests may be used to determine how well the inner ear and brain pathways are working. One of these is otoacoustic emission testing (OAE) that detects sounds given off by the inner ear when responding to sound. This test is often done as part of a newborn screening. A head MRI may be done to help diagnose hearing loss due to an acoustic neuroma.

Presbycusis treatment

Your treatment will depend on the severity of your hearing loss, so some treatments will work better for you than others. There are a number of devices and aids that help you hear better when you have hearing loss. Here are the most common ones:

- Hearing aids are electronic instruments you wear in or behind your ear. They make sounds louder. To find the hearing aid that works best for you, you may have to try more than one. Be sure to ask for a trial period with your hearing aid and understand the terms and conditions of the trial period. Work with your hearing aid provider until you are comfortable with putting on and removing the hearing aid, adjusting the volume level, and changing the batteries. Hearing aids are generally not covered by health insurance companies, although some do. Medicare does not cover hearing aids for adults; however, diagnostic evaluations are covered if they are ordered by a physician for the purpose of assisting the physician in developing a treatment plan.

- Behind-the-ear hearing aids consist of a hard plastic case worn behind the ear and connected to a plastic earmold that fits inside the outer ear. The electronic parts are held in the case behind the ear. Sound travels from the hearing aid through the earmold and into the ear. Behind-the-ear aids are used by people of all ages for mild to profound hearing loss.

- A new kind of behind-the-ear aid is an open-fit hearing aid. Small, open-fit aids fit behind the ear completely, with only a narrow tube inserted into the ear canal, enabling the canal to remain open. For this reason, open-fit hearing aids may be a good choice for people who experience a buildup of earwax, since this type of aid is less likely to be damaged by such substances. In addition, some people may prefer the open-fit hearing aid because their perception of their voice does not sound “plugged up.”

- In-the-ear hearing aids fit completely inside the outer ear and are used for mild to severe hearing loss. The case holding the electronic components is made of hard plastic. Some in-the-ear hearing aids may have certain added features installed, such as a telecoil. A telecoil is a small magnetic coil that allows users to receive sound through the circuitry of the hearing aid, rather than through its microphone. This makes it easier to hear conversations over the telephone. A telecoil also helps people hear in public facilities that have installed special sound systems, called induction loop systems. Induction loop systems can be found in many churches, schools, airports, and auditoriums. In-the-ear hearing aids usually are not worn by young children because the casings need to be replaced often as the ear grows.

- Canal hearing aids fit into the ear canal and are available in two styles. The in-the-canal hearing aid is made to fit the size and shape of a person’s ear canal. A completely-in-canal hearing aid is nearly hidden in the ear canal. Both types are used for mild to moderately severe hearing loss. Because they are small, canal hearing aids may be difficult for a person to adjust and remove. In addition, canal aids have less space available for batteries and additional devices, such as a telecoil. They usually are not recommended for young children or for people with severe to profound hearing loss because their reduced size limits their power and volume.

- Cochlear implants. Cochlear implants are small electronic devices surgically implanted in the inner ear that help provide a sense of sound to people who are profoundly deaf or hard-of-hearing. If your hearing loss is severe, your doctor may recommend a cochlear implant in one or both ears.

- Bone anchored hearing systems bypass the ear canal and middle ear, and are designed to use your body’s natural ability to transfer sound through bone conduction. The sound processor picks up sound, converts it into vibrations, and then relays the vibrations through your skull bone to your inner ear.

- Assistive listening devices include telephone and cell phone amplifying devices, smart phone or tablet “apps,” and closed-circuit systems (hearing loop systems) in places of worship, theaters, and auditoriums.

- Lip reading or speech reading is another option that helps people with hearing problems follow conversational speech. People who use this method pay close attention to others when they talk by watching the speaker’s mouth and body movements. Special trainers can help you learn how to lip read or speech read.

- Zelaya CE, Lucas JW, Hoffman HJ. Self-reported Hearing Trouble in Adults Aged 18 and Over: United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief. Sep 2015.

- Kovacii J, Lajtman Z, Ozegovic I, Knezevic P, Caric T, Vlasic A. Investigation of auditory brainstem function in elderly diabetic patients with presbycusis. Int Tinnitus J. 2009. 15(1):79-82.

- Newman, C.W., Weinstein, B.E., Jacobson, G.P., & Hug, G.A. (1990). The Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults [HHIA]: Psychometric adequacy and audiometric correlates. Ear Hear, 11, 430-433.