Sitosterolemia

Sitosterolemia also known as phytosterolemia, is a rare inherited plant sterol storage disease in which fatty substances (lipids) from vegetable oils, nuts, and other plant-based foods accumulate in the blood and tissues 1. These lipids are called plant sterols or phytosterols. Sitosterol is one of several plant sterols that accumulate in sitosterolemia, with a blood level 30 to 100 times greater than normal. Cholesterol, a similar fatty substance found in animal products, is mildly to moderately elevated in many people with sitosterolemia. Cholesterol levels are particularly high in some affected children. However, some people with sitosterolemia have normal cholesterol levels.

Sitosterolemia is caused by mutations in the ABCG5 or ABCG8 gene. Only 80 to 100 individuals with sitosterolemia have been described in the medical literature 1. A recent report suggests that sitosterolemia has a global prevalence of at least 1 in 2.6 million for an ABCG5 gene mutation and 1 in 360,000 for an ABCG8 gene mutation. The routine clinical test for measuring plasma concentration of cholesterol does not measure plant sterols; therefore sitosterolemia is likely to be underdiagnosed. Studies suggest that the prevalence may be at least 1 in 50,000 people. Men and women are equally likely to have sitosterolemia, and anyone with this condition will have had it from birth, although many are not diagnosed until later.

Researchers identified one individual with sitosterolemia out of 2542 persons in whom plasma concentration of plant sterols was analyzed. These researchers estimated a prevalence of 1/384 to 1/48,076.

Sitosterolemia has been described in various populations, including Hutterite, Amish, Japanese, and Chinese, as well as in other populations. High prevalence has been observed in the following populations:

- The Old Order Amish

- North American Hutterites

- The inhabitants of Kosrae (Micronesia)

Northern European/white individuals more frequently have mutations in the ABCG8 gene. Chinese, Japanese, and Indians tend to have mutations in the ABCG5 gene.

Plant sterols are not produced by the body; they are taken in as components of foods. Signs and symptoms of sitosterolemia may begin to appear early in life after foods containing plant sterols are introduced into the diet, although some affected individuals have no obvious symptoms.

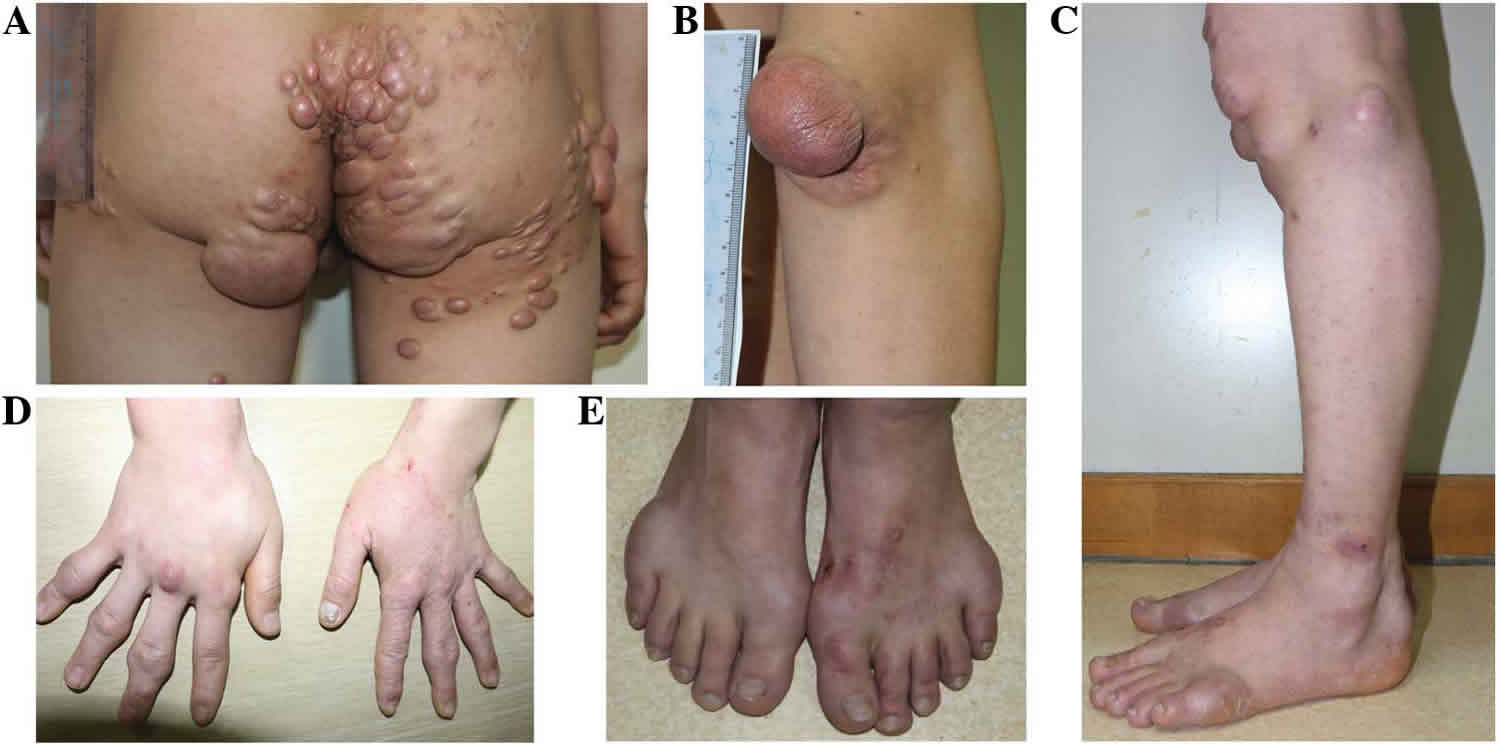

Sitosterolemia is characterized by tendon and tuberous xanthomas and by a strong propensity toward premature coronary atherosclerosis 2. In people with sitosterolemia, accumulation of fatty deposits in arteries (atherosclerosis) can occur as early as childhood. These deposits narrow the arteries and can eventually block blood flow, increasing the chance of a heart attack, stroke, or sudden death.

Some people with sitosterolemia develop small yellowish growths called xanthomas beginning in childhood. Xanthomas consist of accumulated lipids and may be located anywhere on or just under the skin, typically on the heels, knees, elbows, and buttocks. They may also occur in the bands that connect muscles to bones (tendons), including tendons of the hand and the tendon that connects the heel of the foot to the calf muscles (the Achilles tendon). Large xanthomas can cause pain, difficulty with movement, and cosmetic problems.

Joint stiffness and pain resulting from plant sterol deposits may also occur in individuals with sitosterolemia. Less often, affected individuals have blood abnormalities. Occasionally the blood abnormalities are the only signs of the disorder. The red blood cells may be broken down (undergo hemolysis) prematurely, resulting in a shortage of red blood cells (anemia). This type of anemia is called hemolytic anemia. Affected individuals sometimes have abnormally shaped red blood cells called stomatocytes. In addition, the blood cell fragments involved in clotting, called platelets or thrombocytes, may be abnormally large (macrothrombocytopenia).

Sitosterolemia causes

Sitosterolemia is caused by mutations in the ABCG5 or ABCG8 gene. These genes provide instructions for making the two halves of a protein called sterolin. This protein is involved in eliminating plant sterols, which cannot be used by human cells.

Sterolin is a transporter protein, which is a type of protein that moves substances across cell membranes. It is found mostly in cells of the intestines and liver. After plant sterols in food are taken into intestinal cells, the sterolin transporters in these cells pump them back into the intestinal tract, decreasing absorption. Sterolin transporters in liver cells pump the plant sterols into a fluid called bile that is released into the intestine. From the intestine, the plant sterols are eliminated with the feces. This process removes most of the dietary plant sterols, and allows only about 5 percent of these substances to get into the bloodstream. Sterolin also helps regulate cholesterol levels in a similar fashion; normally about 50 percent of cholesterol in the diet is absorbed by the body.

Mutations in the ABCG5 or ABCG8 gene that cause sitosterolemia result in a defective sterolin transporter and impair the elimination of plant sterols and, to a lesser degree, cholesterol from the body. These fatty substances build up in the arteries, skin, and other tissues, resulting in atherosclerosis, xanthomas, and the additional signs and symptoms of sitosterolemia. Excess plant sterols, such as sitosterol, in red blood cells likely make their cell membranes stiff and prone to rupture, leading to hemolytic anemia. Changes in the lipid composition of the membranes of red blood cells and platelets may account for the other blood abnormalities that sometimes occur in sitosterolemia.

Sitosterolemia inheritance pattern

This condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means both copies of the gene in each cell have mutations. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive condition each carry one copy of the mutated gene, but they typically do not show signs and symptoms of the condition.

It is rare to see any history of autosomal recessive conditions within a family because if someone is a carrier for one of these conditions, they would have to have a child with someone who is also a carrier for the same condition. Autosomal recessive conditions are individually pretty rare, so the chance that you and your partner are carriers for the same recessive genetic condition are likely low. Even if both partners are a carrier for the same condition, there is only a 25% chance that they will both pass down the non-working copy of the gene to the baby, thus causing a genetic condition. This chance is the same with each pregnancy, no matter how many children they have with or without the condition.

- If both partners are carriers of the same abnormal gene, they may pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. This occurs randomly.

- Each child of parents who both carry the same abnormal gene therefore has a 25% (1 in 4) chance of inheriting a abnormal gene from both parents and being affected by the condition.

- This also means that there is a 75% ( 3 in 4) chance that a child will not be affected by the condition. This chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys or girls.

- There is also a 50% (2 in 4) chance that the child will inherit just one copy of the abnormal gene from a parent. If this happens, then they will be healthy carriers like their parents.

- Lastly, there is a 25% (1 in 4) chance that the child will inherit both normal copies of the gene. In this case the child will not have the condition, and will not be a carrier.

These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

Figure 1 illustrates autosomal recessive inheritance. The example below shows what happens when both dad and mum is a carrier of the abnormal gene, there is only a 25% chance that they will both pass down the abnormal gene to the baby, thus causing a genetic condition.

Figure 1. Sitosterolemia autosomal recessive inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Sitosterolemia symptoms

Signs and symptoms of sitosterolemia vary from person to person, but any one of these symptoms alone is reason enough to be tested for it. Some patients present with high cholesterol. While most cases of high cholesterol are not caused by sitosterolemia, if a patient’s cholesterol varies greatly with diet, but does not respond well to statins, then it could be a sign of sitosterolemia.

Patients with sitosterolemia may present with xanthomas, which are visible fatty deposits under the skin. They can be located anywhere, but frequently occur around the knees, heels, elbows, buttocks, or around the eyes. However, the absence of xanthomas should never be used to rule out sitosterolemia.

Deposits of plant sterols sometimes cause joint stiffness and pain. Some sitosterolemia patients only present with blood abnormalities such as low platelet count (thrombocytopenia), abnormally large platelets (macrothrombocytopenia) or abnormally shaped red blood cells (stomatocytes).

All sitosterolemia patients will have elevated levels of plant sterols in their blood.

Sitosterolemia diagnosis

The diagnosis of sitosterolemia is established in individuals who have greatly increased plant sterol concentrations (especially sitosterol, campesterol, and stigmasterol) in plasma and tissues. Shellfish sterols can also be elevated. Since standard lipid profiles do not test for the presence of plant sterols, a blood sample will have to be sent to a lab that performs gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). A blood test that reveals frank elevation in phytosterol levels is considered diagnostic for sitosterolemia. Genetic testing for mutations in the ABCG8 and ABCG5 genes is available to confirm the diagnosis.

In untreated individuals with sitosterolemia, the sitosterol concentration can as high as 10 to 65 mg/dL. Plasma concentrations of sitosterol above 1 mg/dL are considered to be diagnostic of sitosterolemia (except in infants, in whom further testing may be necessary.

False positive results have been observed:

- Normal infants ingesting commercial infant formula (which contains plant sterols) may have a transient increase in plasma plant sterols.

- Patients with cholestasis or liver disease who are on parenteral nutrition (which contains plant sterols) may be unable to effectively clear the plant sterols.

- Carriers of only one gene mutation for sitosterolemia may occasionally have mildly elevated concentration of sitosterol (Note, however, that plasma concentrations of sitosterol are usually normal in carriers.).

False negative results can be observed in:

- Individuals using ezetimibe or ezetimibe combinations, or bile acid binding resin;

AND/OR

- Individuals on a diet low in plant-derived foods.

Clinical testing and work up

Plasma concentrations of plant sterols (primarily beta-sitosterol and campesterol) and cholesterol should be monitored, and the size, number, and distribution of xanthomas should be monitored at least every six to 12 months.

Platelet count should be monitored for thrombocytopenia, complete blood count (CBC) for evidence of hemolytic anemia, and liver enzymes for elevation beginning at the time of diagnosis with the frequency determined by the severity of the clinical and biochemical findings.

Surveillance for atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease is suggested, with the level of monitoring determined by the severity of the clinical and biochemical findings.

Sitosterolemia treatment

Treatment aims to reduce plasma concentration of plant sterols to as close as possible to normal concentrations (i.e., <1 mg/dL), to control plasma concentration of cholesterol, and to prevent xanthoma formation and/or reduce the size and number of xanthomas. Current treatment therapies focus on the following:

- A diet low in shellfish sterols and plant sterols (i.e., avoidance of vegetable oils, margarine, nuts, seeds, avocados, chocolate, and shellfish) in conjunction with ezetimibe or other medications

- The sterol absorption inhibitor: ezetimibe (10 mg/d) which alone may be sufficient. Ezetimibe is the current standard of care for patients with sitosterolemia. Although ezetimibe 10 mg daily lowers plant sterol levels in the blood of patients with sitosterolemia, it still remains very elevated; therefore ezetimibe therapy should be combined with other therapies to further reduce plant sterols levels. One study is currently testing the effect of a bile acid sequestrant such as colesevelam in combination with ezetimibe. When tolerated, combined treatments can decrease cholesterol and sitosterol levels by 10-50%. Higher doses of Ezetimibe above 10mg do not appear to further reduce plant sterol levels. Since no studies have been published on the fetal effects of ezetimibe, it should not be used during pregnancy.

- Bile acid sequestrants such as Cholestyramine (8-15 g/day) which may be considered in those with incomplete response to ezetimibe. Bile acid sequestrants work by binding sterols to bile which allows for excretion of the plant sterols.

Treatments should begin at the time of diagnosis. When tolerated, the combined treatments can decrease the plasma concentrations of cholesterol and sitosterol by 10% to 50%. Often existing xanthomas regress.

Arthritis, arthralgias, anemia, thromobocytopenia, and/or splenomegaly require treatment, the first step being management of the sitosterolemia, followed by routine management of the finding (by the appropriate consultants) as needed.

Sitosterolemia does not respond well to standard statin treatment.

Foods with high plant sterol content including shellfish, vegetable oils, margarine, nuts, avocados, and chocolate should be avoided or taken in moderation due to increased intestinal absorption of plant sterols in people with sitosterolemia.

Sitosterolemia diet

With the advent of treatment with ezetimibe, dietary therapy may not be needed 3.

If dietary therapy is indicated, a diet with the lowest possible amounts of plant sterols is advised. Guidelines are as follows:

- Eliminate all sources of vegetable fats.

- Avoid all plant foods high in fat, such as olives and avocados.

- Eliminate vegetable oils, shortening, and margarine.

- Eliminate nuts, seeds, and chocolate.

- Avoid shellfish.

- Cereal products without germ are allowed.

- Food derived from animal sources with cholesterol as the dominant sterol is allowed.

Diet is quite restrictive, but references for acceptable commercial products, possible menus, and recipes are available 4.

Sitosterolemia prognosis

The prognosis for patients with sitosterolemia is not clear, given the extreme rarity of the disease 3. Early diagnosis and treatment correlate with a better outcome. Left untreated, sitosterolemia has significant morbidity and increased risk of early mortality. The availability of ezetimibe may dramatically improve the prognosis.

References- Sitosterolemia https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/sitosterolemia

- Patil S, Kharge J, Bagi V, Ramalingam R. Tendon xanthomas as indicators of atherosclerotic burden on coronary arteries. Indian Heart J. 2013 Jul-Aug. 65(4):491-2.

- Sitosterolemia (Phytosterolemia). https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/948892-overview

- Kuksis I, Myher JJ, Marai L, et al. Fatty acid composition of individual plasma steryl esters in phytosterolemia and xanthomatosis. Lipids. 1986. 21:371-7.