What is salpingitis

Salpingitis is an acute inflammation of the fallopian tubes, the tubes which connect a woman’s ovaries to her uterus (womb). Salpingitis is usually caused by an infection in the vagina or uterus. Salpingitis is most commonly caused by sexually transmitted micro-organisms in adolescent and adult women 1. Salpingitis is very uncommon in premenarchal or sexually inactive girls 2. Salpingitis is a type of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which is a clinical syndrome comprising a spectrum of infectious and inflammatory diseases of the upper female genital tract 3. The diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) can include any combination of endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, or pelvic peritonitis 4. Each of these disease processes is characterized by ascending spread of organisms from the vagina or cervix to the structures of the upper female genital tract. Although pelvic inflammatory disease is most notable for the associated risk of severe, long-term sequelae, the infections may be asymptomatic (“silent”) or overt with mild to severe symptoms. The clinical syndrome of acute (and subacute) pelvic inflammatory disease—usually defined as symptoms for fewer than 30 days—can be due to a variety of pathogens, often including, but not limited to, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis 5. In contrast, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (symptoms for greater than 30 days) is a separate disorder usually related to infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Actinomyces species (Table 1) 5.

There is no single diagnostic test for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and in the United States pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is not a nationally notifiable disease; thus, it can be difficult to accurately estimate the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease 6. Review of a national admission database in 2001 estimated more than 750,000 cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) occurred in the United States 7. More recent data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013–2014 estimated a prevalence of self-reported lifetime pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) of 4.4% among sexually experienced women 18-44 years of age, which corresponds with an estimate of 2.5 million women aged 18-44 years ever having pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in their lifetime 8. Available data point to an overall trend of decline in the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in the United States. A review of national insurance claims found a 25.5% decline in cases from 2001 to 2005 (317.0 to 236.0 per 100,000 enrollees) 9. The number of initial visits to office-based physicians for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) declined by 71% between 2005 and 2014—from 176,000 visits in 2005 to 51,000 visits in 2014 10. Data from 1995 through 2013 likewise show a consistent decrease in the lifetime prevalence of treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and these decreases occurred across multiple racial/ethnic groups 11.

The trend of decreasing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is primarily attributed to an increase in effective screening and treatment of chlamydial and gonococcal infections in adolescents and young women 12. Although total rates of infection with C. trachomatis have increased in some populations, the rates of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) have consistently fallen. This highlights the effectiveness of treating lower tract chlamydial infections for prevention of progression to upper tract disease. Of note, several studies suggest a decrease in the proportion of cases attributable to chlamydial infection. As pathogens other than C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae are becoming more prominent as a cause of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), the importance of addressing risk behaviors and monitoring for infections caused by these other organisms may become more important 13.

Table 1. Clinical Classification of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Likely Microbial Causes

| Clinical Syndrome | Causes |

|---|---|

| Acute pelvic inflammatory disease (≤30 days’ duration) | Cervical pathogens (Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Mycoplasma genitalium) Bacterial vaginosis pathogens (Peptostreptococcus species, Bacteroides species, Atopobium species, Leptotrichia species, M. hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Clostridia species) Respiratory pathogens (Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, group A streptococci, and Staphylococcus aureus) Enteric pathogens (Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, group B streptococci, and Campylobacter species) |

| Subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease | Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

| Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (>30 days’ duration) | Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Actinomyces species |

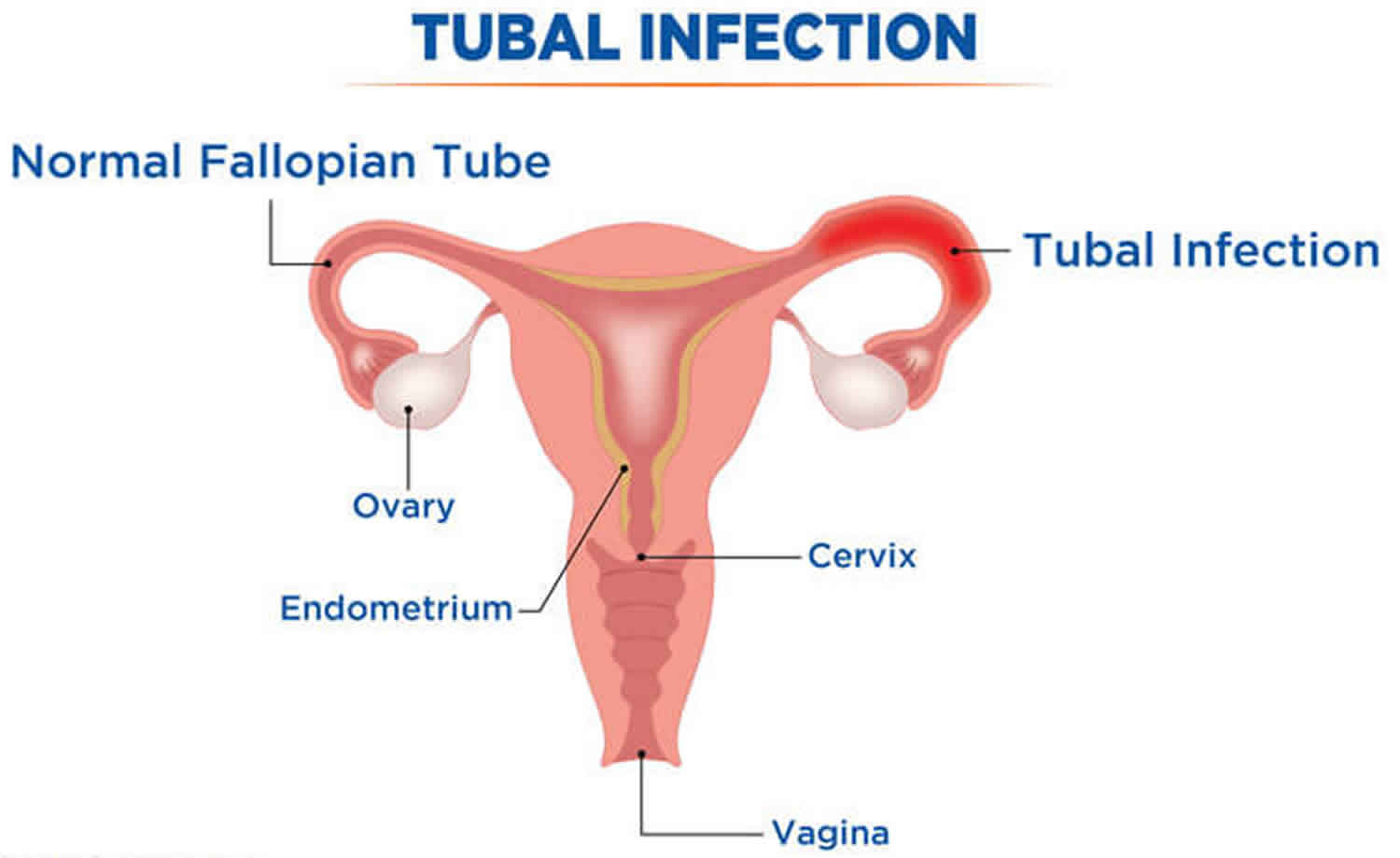

Figure 1. Fallopian tube (Uterine tube)

Figure 2. Fallopian tube location

Salpingitis isthmica nodosa

Salpingitis isthmica nodosa is a condition of nodular thickening of the proximal fallopian tube enclosing cystically dilated glands trapped in muscular layer 14. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa commonly occurs in the age group of 25 -60 years women with average age at diagnosis being 30 years 15. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa is usually bilateral and the patients presents with recurrent ectopic pregnancies and primary infertility 15. Hysterosalpingography is diagnostic for salpingitis isthmica nodosa, shows 2-mm accumulations of contrast medium observed within the diverticula with associated irregularities in the tubal lumen 15.

Incidence of salpingitis isthmica nodosa in healthy, fertile women ranges from 0.6% to 11%, but it is significantly more common in the setting of ectopic pregnancy and infertility 14.

The cause of salpingitis isthmica nodosa is unknown. Salpingitis Isthmica Nodosa was pathologically first described by Chiari 16 and attributed to be an inflammatory aetiology or adenomyosis-like process 17. Others proposed congenital Wolffian or mesonephric rests 18, neoplasia 19 or a late result of chronic tubal spasm similar to colonic diverticulosis 20.

The incidence of salpingitis isthmica nodosa in the normal population is reported as between 0.6% and 11% 21, with the higher incidence in a Jamaican population. It has been associated with ectopic tubal pregnancies with a wide range of incidence (2.8%–57%) 22 and in 46% if the isthmic site-specific ectopic pregnancy is considered separately 23. The association of salpingitis isthmica nodosa and isthmic ectopic pregnancy was determined by review of resected tubal segments. Salpingitis Isthmica Nodosa was noted in 17 of 37 cases (45.9%) of isthmic ectopic pregnancy. Salpingitis Isthmica Nodosa places the patient at risk for recurrent ectopic pregnancy or infertility 24.

Microscopic examination of the tube shows dispersed glands of tubal epithelium surrounded by bands of muscle fibers 23. On hysterosalpingography, diagnosis of Salpingitis Isthmica Nodosa may be confused with tubal endometriosis. However, presence of tubal epithelium lining glands on histopathological examination rules out endometriosis 25.

Salpingitis isthmica nodosa is significantly associated with the recurrent ectopic pregnancies and infertility; hence, it is important to rule out salpingitis isthmica nodosa in such cases 26.

Salpingitis causes

Salpingitis is an infection caused by bacteria. When bacteria from the vagina or cervix travel to your womb, fallopian tubes, or ovaries, they can cause an infection.

Most of the time, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is caused by bacteria from chlamydia and gonorrhea. These are sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Having unprotected sex with someone who has an STI can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

Bacteria normally found in the cervix can also travel into the uterus and fallopian tubes during a medical procedure such as:

- Childbirth

- Endometrial biopsy (removing a small piece of your womb lining to test for cancer)

- Getting an intrauterine device (IUD)

- Miscarriage

- Abortion

In the United States, nearly 1 million women have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) each year. About 1 in 8 sexually active girls will have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) before age 20.

You are more likely to get pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) if:

- You have a sex partner with gonorrhea or chlamydia.

- You have sex with many different people.

- You have had an STI in the past.

- You have recently had pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

- You have contracted gonorrhea or chlamydia and have an IUD.

- You have had sex before age 20.

Risk factors for salpingitis

Epidemiologic studies have revealed numerous risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease and many of these risk factors overlap with those known to be associated with acquisition of infections that cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Multiple partners, age younger than 20 years, and current or prior infection with gonorrhea or chlamydia have consistently been demonstrated as significant risk factors 27. Other possible risk factors include history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), male partners with gonorrhea or chlamydia, current douching, insertion of intrauterine device (IUD), bacterial vaginosis, and oral contraceptive use 11. The following provides more detail on the major risk factors:

- Age and Age of Sexual Debut: Several studies have identified age less than 20 years as a major risk factor for the development of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) 27. The increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in younger women correlates with the high rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea infection in female adolescents and young adult women. In addition, cervical ectopy—the composition of the cervical epithelium that is often present in adolescents—allows for more efficient access of infectious pathogens to the vulnerable target cells. Younger sexual debut is also a risk factor for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). In the NHANES 2013-2014, the lifetime pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) prevalence in sexually experienced women aged 18-44 years was higher than in those with a younger sexual debut 8.

- Number of Sexual Partners: Several studies have shown a correlation with greater number of sexual partners and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Most recently, in NHANES 2013-2014, the lifetime pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) prevalence was approximately three times greater in women with 10 or more lifetime vaginal sex partners than in women with one partner 8.

- History of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): A prior history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) increases the risk for developing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) 28. The damage that occurs to the fallopian tube mucosa during an episode of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) makes women more susceptible to recurrent infection. Having a history of a gonorrheal or chlamydial infection increases the likelihood of recurrent disease, which, in turn, increases the risk for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). A woman’s risk also increases if her male partner has gonorrhea or chlamydia.

- Vaginal Douching: Douching is thought to increase the risk for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) because it contributes to vaginal flora changes, epithelial damage, and disruption of the cervical mucous barrier, all of which can increase the likelihood of developing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) 11. The relationship between douching has been called into question in more recent studies and the recommendation for or against vaginal douching is currently subject to debate 29. The relationship of bacterial vaginosis (BV) to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is similarly unclear. Although the anaerobic bacteria associated with BV have been detected in the upper genital tract in association with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), epidemiologic analyses have not consistently shown a clear association between bacterial vaginosis and development of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) 29.

- Intrauterine Device (IUD): The insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD) has been shown to increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) approximately six-fold within the first 21 days of placement, but after 21 days, the risk returns to baseline 30. In addition, the CDC describes mucopurulent cervicitis or current N. gonorrhoeae and/or C. trachomatis infection as “unacceptable health risk” and thus a contraindication to IUD insertion 31. Notably, recent studies have revealed that the rates of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) among new IUD users were 1% or below for both those who tested positive for N. gonorrhoeae and/or C. trachomatis and those who tested negative 32. The authors of these recent studies suggest that women without clinical evidence of active infection can have intrauterine system placement and sexually transmitted infection screening, if indicated, on the same day. This remains an active area of investigation.

- Oral Contraceptive Use: Oral contraceptive (OC) use may increase the risk of cervical chlamydial infection due to cervical ectopy associated with oral contraceptive use. Oral contraceptive use also causes thickening of the cervical mucous, which may be protective against lower genital tract organisms ascending into the upper genital tract. Overall, many providers conclude that since the absolute risk of pelvic infection is small (1.6 cases per 1,000 woman-years in a meta-analysis) the benefits of these birth-control measures likely outweigh the risks 30.

Salpingitis prevention

Get prompt treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

You can help prevent pelvic inflammatory disease by practicing safer sex:

- The only absolute way to prevent an sexually transmitted infection (STI) is to not have sex (abstinence).

- You can reduce your risk by having a sexual relationship with only one person. This is called being monogamous.

- Your risk will also be reduced if you and your sexual partners get tested for STIs before starting a sexual relationship.

- Using a condom every time you have sex also reduces your risk.

Here is how you can reduce your risk of pelvic inflammatory disease:

- Get regular sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening tests.

- If you are a new couple, get tested before starting to have sex. Testing can detect infections that are not causing symptoms.

- If you are a sexually active woman age 24 or younger, get screened each year for chlamydia and gonorrhea.

- All women with new sexual partners or multiple partners should also be screened.

Salpingitis symptoms

Common symptoms of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) include:

- Fever

- Pain or tenderness in the pelvis, lower belly, or lower back

- Fluid from your vagina that has an unusual color, texture, or smell

Other symptoms that may occur with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID):

- Bleeding after intercourse

- Chills

- Being very tired

- Pain when you urinate

- Having to urinate often

- Period cramps that hurt more than usual or last longer than usual

- Unusual bleeding or spotting during your period

- Not feeling hungry

- Nausea and vomiting

- Skipping your period

- Pain when you have intercourse

Women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) present with a wide array of clinical manifestations that range from virtually asymptomatic to severe and debilitating symptoms. You can have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and not have any severe symptoms. For example, chlamydia can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) with no symptoms. Women who have an ectopic pregnancy or who are infertile often have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) caused by chlamydia. An ectopic pregnancy is when an egg grows outside of the uterus. It puts the mother’s life in danger.

Other women with acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) may experience subtle, nonspecific symptoms such as dyspareunia, dysuria, or gastrointestinal symptoms, which they may not attribute to pelvic infection 33. This leads to a failure to seek care for many patients. When mild to moderate symptoms of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) do occur, women may describe lower abdominal or pelvic pain, cramping, or painful urination (dysuria). They may also exhibit signs such as intermittent or post-coital vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, or fever. Systemic signs, such as fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting are often absent in mild to moderate cases. On physical examination, there may be no external evidence of infection, but uterine tenderness, cervical motion pain, or adnexal tenderness is most often present. In severe pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), women appear very ill with fever, chills, purulent vaginal discharge, nausea, vomiting, and elevated white blood cell count (WBC). Other laboratory indicators, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), may also be elevated. As seen with mild and moderate disease, uterine tenderness, cervical motion pain, with or without adnexal tenderness are expected. Available data suggest that some women develop subclinical upper genital tract infection that can nevertheless result in long-term sequelae, including infertility 34; the development of “silent pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)” poses a major diagnostic and treatment challenge 35.

Salpingitis complications

Pelvic inflammatory disease infections can cause scarring of the pelvic organs. This can lead to:

- Long-term (chronic) pelvic pain

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Infertility

- Tubo-ovarian abscess

If you have a serious infection that does not improve with antibiotics, you may need surgery.

Acute complications

Women with acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) can develop a range of inflammatory complications, including local tissue damage, fallopian tube swelling, tubal occlusion, and development of adhesions 36. Although uncommon, the adhesion formation can involve the liver capsule and cause a perihepatitis referred to as the Fitz-Hugh Curtis Syndrome 37. The development of a tubo-ovarian abscess can occur as a subacute complication of acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and some women will have a tubo-ovarian abscess at the time they present with acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) 38.

Chronic complications

The consequences of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), including ectopic pregnancy, infertility, or chronic pelvic pain may occur after a single episode of symptomatic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). One recent retrospective cohort study 39 of women admitted with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or tubo-ovarian abscess found that, in follow-up, 25.5% of women met the criteria of infertility, 16.0% had recurrent pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and 13.8% reported chronic pelvic pain. Several studies have demonstrated that multiple episodes or more severe cases dramatically increase women’s risk for infertility as well as for ectopic pregnancy 40. Appropriate therapy has been shown to significantly decrease the rate of long-term sequelae 41. The risk of ectopic pregnancy is increased 6- to 10-fold after pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Tubal infertility occurs in 8% of women after one episode of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), in 20% of women after two episodes, and in 50% of women after three episodes. If a tubo-ovarian abscess is present, the outcome is largely dependent upon whether there is intra-abdominal rupture and what degree of surgical intervention was required. If intra-abdominal rupture is suspected, and patients are treated with fertility-preserving, conservative surgery, the reported subsequent pregnancy rate is 25%. For women without rupture who are treated with medical management alone, reported pregnancy rates vary between 4% and 15% 36.

Salpingitis diagnosis

Your health care provider may do a pelvic exam to look for:

- Bleeding from your cervix. The cervix is the opening to your uterus.

- Fluid coming out of your cervix.

- Pain when your cervix is touched.

- Tenderness in your uterus, tubes, or ovaries.

You may have lab tests to check for signs of body-wide infection:

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- White blood cell (WBC) count

Other tests include:

- A swab taken of your vagina or cervix. This sample will be checked for gonorrhea, chlamydia, or other causes of PID.

- Pelvic ultrasound or CT scan to see what else may be causing your symptoms. Appendicitis or pockets of infection around your tubes and ovaries, called tubo-ovarian abscess, may cause similar symptoms.

- Pregnancy test.

Acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is difficult to diagnose because of the wide variation in symptoms and signs associated with this condition 35. Many women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) have subtle or nonspecific symptoms or are asymptomatic. Delay in diagnosis and treatment probably contributes to inflammatory sequelae in the upper reproductive tract. Laparoscopy can be used to obtain a more accurate diagnosis of salpingitis and a more complete bacteriologic diagnosis. However, this diagnostic tool frequently is not readily available, and its use is not easily justifiable when symptoms are mild or vague. Moreover, laparoscopy will not detect endometritis and might not detect subtle inflammation of the fallopian tubes. Consequently, a diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) usually is based on imprecise clinical findings 42.

Data indicate that a clinical diagnosis of symptomatic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) has a positive predictive value for salpingitis of 65%–90% compared with laparoscopy 43. The positive predictive value of a clinical diagnosis of acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) depends on the epidemiologic characteristics of the population, with higher positive predictive values among sexually active young women (particularly adolescents), women attending STD clinics, and those who live in communities with high rates of gonorrhea or chlamydia. Regardless of positive predictive value, no single historical, physical, or laboratory finding is both sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Combinations of diagnostic findings that improve either sensitivity (i.e., detect more women who have pelvic inflammatory disease) or specificity (i.e., exclude more women who do not have pelvic inflammatory disease) do so only at the expense of the other. For example, requiring two or more findings excludes more women who do not have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and reduces the number of women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) who are identified.

Many episodes of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) go unrecognized. Although some cases are asymptomatic, others are not diagnosed because the patient or the health-care provider fails to recognize the implications of mild or nonspecific symptoms or signs (e.g., abnormal bleeding, dyspareunia, and vaginal discharge). Even women with mild or asymptomatic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) might be at risk for infertility 44. Because of the difficulty of diagnosis and the potential for damage to the reproductive health of women, health-care providers should maintain a low threshold for the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) 45. The following recommendations for diagnosing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) are intended to help health-care providers recognize when pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) should be suspected and when additional information should be obtained to increase diagnostic certainty. Diagnosis and management of other common causes of lower abdominal pain (e.g., ectopic pregnancy, acute appendicitis, ovarian cyst, and functional pain) are unlikely to be impaired by initiating antimicrobial therapy for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

Presumptive treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) should be initiated in sexually active young women and other women at risk for STDs if they are experiencing pelvic or lower abdominal pain, if no cause for the illness other than pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) can be identified, and if one or more of the following minimum clinical criteria are present on pelvic examination:

- cervical motion tenderness

or - uterine tenderness

or - adnexal tenderness.

The requirement that all three minimum criteria be present before the initiation of empiric treatment could result in insufficient sensitivity for the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). After deciding whether to initiate empiric treatment, clinicians should also consider the risk profile for STDs.

More elaborate diagnostic evaluation frequently is needed because incorrect diagnosis and management of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) might cause unnecessary morbidity. For example, the presence of signs of lower-genital–tract inflammation (predominance of leukocytes in vaginal secretions, cervical exudates, or cervical friability), in addition to one of the three minimum criteria, increases the specificity of the diagnosis. One or more of the following additional criteria can be used to enhance the specificity of the minimum clinical criteria and support a diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID):

- oral temperature >101°F (>38.3°C);

- abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability;

- presence of abundant numbers of WBC on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid;

- elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate;

- elevated C-reactive protein; and

- laboratory documentation of cervical infection with N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis.

Most women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) have either mucopurulent cervical discharge or evidence of white blood cells on a microscopic evaluation of a saline preparation of vaginal fluid (i.e., wet prep). If the cervical discharge appears normal and no white blood cells are observed on the wet prep of vaginal fluid, the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is unlikely, and alternative causes of pain should be considered. A wet prep of vaginal fluid also can detect the presence of concomitant infections (e.g., bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis).

The most specific criteria for diagnosing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) include:

- endometrial biopsy with histopathologic evidence of endometritis;

- transvaginal sonography or magnetic resonance imaging techniques showing thickened, fluid-filled tubes with or without free pelvic fluid or tubo-ovarian complex, or Doppler studies suggesting pelvic infection (e.g., tubal hyperemia); or

- laparoscopic findings consistent with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

A diagnostic evaluation that includes some of these more extensive procedures might be warranted in some cases. Endometrial biopsy is warranted in women undergoing laparoscopy who do not have visual evidence of salpingitis, because endometritis is the only sign of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) for some women.

Salpingitis treatment

Your doctor will often have you start taking antibiotics while waiting for your test results.

If you have mild pelvic inflammatory disease:

- Your doctor will give you a shot containing an antibiotic.

- You will be sent home with antibiotic pills to take for up to 2 weeks.

- You will need to follow-up closely with your provider.

If you have more severe pelvic inflammatory disease:

- You may need to stay in the hospital.

- You may be given antibiotics through a vein (IV).

- Later, you may be given antibiotic pills to take by mouth.

There are many different antibiotics that can treat pelvic inflammatory disease. Some are safe for pregnant women. Which type you take depends on the cause of the infection. You may receive a different treatment if you have gonorrhea or chlamydia.

If your pelvic inflammatory disease is caused by an sexually transmitted infection (STI) like gonorrhea or chlamydia, your sexual partner must be treated as well.

- If you have more than one sexual partner, they must all be treated.

- If your partner is not treated, he or she can infect you again, or can infect other people in the future.

- Both you and your partner must finish taking all of the prescribed antibiotics.

- Use condoms until you both have finished taking antibiotics.

Hospital admission criteria with acute pelvic inflammatory disease

The decision of whether to admit for inpatient monitoring can be challenging. The CDC 35 recommends this decision be made based on provider judgment with certain criteria strongly indicating a need for inpatient monitoring and care. The STD guidelines list the following suggested criteria for hospitalization of women with pelvic inflammatory disease.

- Inability to exclude surgical emergencies (e.g. appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy)

- Tubo-ovarian abscess

- Pregnancy

- Severe illness, nausea and vomiting, or high fever

- Nonresponse to oral therapy—defined as failure to respond clinically to outpatient antimicrobial therapy within 48 to 72 hours, or the inability to tolerate an outpatient oral regimen

- Current immunodeficiency (HIV infection with low CD4 cell count, immunosuppressive therapy)

There is no evidence to suggest that adolescents have improved outcomes from hospitalization for treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease, and clinical response rates to outpatient care are similar between younger and older women; the decision to hospitalize adolescents should thus be based on the same criteria used for older women 35. However, determination of whether adolescents can comply with outpatient management should depend on developmental stage and availability of support systems (such as parent/guardian involvement), and those youth receiving outpatient treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease warrant close monitoring to ensure medication adherence.

Parenteral Treatment

There are several randomized trials demonstrating the efficacy of parenteral regimens for treatment of acute pelvic inflammatory disease 35. Three regimens are recommended as initial parenteral therapy for pelvic inflammatory disease, with subsequent transition to oral therapy based on clinical improvement (usually around 24 to 48 hours of parenteral therapy) 3. Doxycycline may be given via oral route due to pain with IV infusion. For initial parenteral therapy, third-generation cephalosporins (e.g. ceftizoxime, cefotaxime, and ceftriaxone) are less active than cefotetan or cefoxitin against anaerobic bacteria and thus are less preferable. Ampicillin-sulbactam plus doxycycline is considered an alternative initial parenteral regimen; this combination is effective against C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and anaerobes. Short-term studies with ampicillin-sulbactam plus doxycycline have shown similar clinical cure rates as seen with recommended regimens.[60] Limited data support the use of other parenteral regimens.

Recommended Parenteral Regimens 3:

- Cefotetan 2 g IV every 12 hours PLUS Doxycycline 100 mg orally or IV every 12 hours

OR - Cefoxitin 2 g IV every 6 hours PLUS Doxycycline 100 mg orally or IV every 12 hours

OR - Clindamycin 900 mg IV every 8 hours PLUS Gentamicin loading dose IV or IM (2 mg/kg), followed by a maintenance dose (1.5 mg/kg) every 8 hours. Single daily dosing (3–5 mg/kg) can be substituted.

Intramuscular/Oral Treatment

Intramuscular/oral therapy can be considered for women with mild-to-moderately severe acute pelvic inflammatory disease, because the clinical outcomes among women treated with these regimens are similar to those treated with intravenous therapy 46. All of the oral regimen components should be continued for a total of 14 days. Patients on oral therapy should be followed up within 72 hours, at which time they should show substantial clinical improvement. If no improvement occurs by 72 hours, the patient should be re-evaluated to confirm the diagnosis and should be switched to parenteral therapy, either in an outpatient or inpatient setting 3. The addition of metronidazole should be considered, as anaerobic organisms are suspected in many cases. Metronidazole will also treat bacterial vaginosis, which frequently is associated with pelvic inflammatory disease.

Recommended Intramuscular/Oral Regimens 3

- Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM in a single dose PLUS Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days WITH* or WITHOUT Metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 14 days

OR - Cefoxitin 2 g IM in a single dose and Probenecid, 1 g orally administered concurrently in a single dose PLUS Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days WITH or WITHOUT Metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 14 days

OR - Other parenteral third-generation cephalosporin (e.g., ceftizoxime or cefotaxime) PLUS Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days WITH* or WITHOUT Metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 14 days

*The recommended third-generation cephalsporins are limited in the coverage of anaerobes. Therefore, until it is known that extended anaerobic coverage is not important for treatment of acute pelvic inflammatory disease, the addition of metronidazole to treatment regimens with third-generation cephalosporins should be considered 47.

These regimens provide coverage against frequent etiologic agents of pelvic inflammatory disease, but the optimal choice of a cephalosporin is unclear. Cefoxitin, a second-generation cephalosporin, has better anaerobic coverage than ceftriaxone, and in combination with probenecid and doxycycline has been effective in short-term clinical response in women with pelvic inflammatory disease. Ceftriaxone has better coverage against N. gonorrhoeae. The addition of metronidazole will also effectively treat BV, which is frequently associated with pelvic inflammatory disease.

Alternative Intramuscular/Oral Regimens

Azithromycin has shown short-term clinical effectiveness when used as monotherapy (500 mg IV daily for 1 to 2 doses, followed by 250 mg orally daily for 12-14 days) or in combination with metronidazole 48. Similar efficacy has been reported with ceftriaxone (250 mg IM as a single dose) given with either azithromycin 1 g weekly for 2 weeks or doxycycline twice daily for 14 days 49. Due to increasing rates of resistance in N. gonorrhoeae, the CDC no longer recommends regimens including a quinolone for routine treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. In cases of documented cephalosporin allergy, use of levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily, ofloxacin 400 mg twice daily, or moxifloxacin 400 mg orally once daily with metronidazole for 14 days (500 mg orally twice daily) can be considered 50. If a fluoroquinolone-containing regimen is used, diagnostic tests for gonorrhea must be obtained before instituting therapy. If the culture for gonorrhea is positive, treatment should be based on results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing. If the isolate is determined to be quinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae or if antimicrobial susceptibility cannot be assessed (e.g. if only nucleic acid amplification [NAAT] testing is available), consultation with an infectious diseases specialist is recommended.

Management of pelvic inflammatory disease in women with HIV Infection

The general antimicrobial therapy management of pelvic inflammatory disease in women with HIV infection is the same as in women who are not infected with HIV. Some women with HIV infection and pelvic inflammatory disease have an altered immune response to an upper genital tract infection, which may contribute to a reduced response to antimicrobial therapy, longer hospital courses, and a higher rate of required surgical intervention 51.

Management of Suspected Tubo-Ovarian Abscess

Patients suspected of having a tubo-ovarian abscess should be admitted to the hospital for more intensive management. Patients should promptly receive intravenous antimicrobials to cover gram-negative and gram-positive organisms with consideration of additional coverage for anaerobic organisms. Imaging is helpful to confirm the presence of abscess and to allow tracking for improvement on therapy. The CDC does not recommend a specific regimen for treatment of tubo-ovarian abscess. Combinations of ampicillin, clindamycin, and gentamicin have been used with success in the past 52. The CDC recommends a minimum of 24 hours of inpatient observation for women with suspected tubo-ovarian abscess. Those that fail to defervesce or improve symptomatically, or have persistent abscess on interval imaging should be evaluated for possible surgical intervention. Notably, 85% of abscesses with a diameter of 4 to 6 cm resolve with antibiotic therapy alone, whereas only 40% of those 10 cm or larger respond 53.

Follow-Up

Patients should be reexamined within 72 hours after initiation of therapy and should demonstrate substantial clinical improvement, typically manifested as resolution of fever, reduction in rebound or direct abdominal tenderness, and diminution in uterine, adnexal, and cervical motion tenderness. Patients who do not improve usually require hospitalization, additional diagnostic tests, and possible surgical intervention. Women diagnosed with chlamydial or gonococcal infections have a high rate of reinfection within 6 months of treatment. Retesting of all women who have been diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea is recommended 3-6 months after treatment, regardless of whether their sex partners were treated. All women diagnosed with acute pelvic inflammatory disease should be offered HIV testing. There are no specific recommendations for follow-up regarding possible long-term sequelae after treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease or tubo-ovarian abscess. It is thus imperative that patients receive adequate counseling and education at the time of initial diagnosis and treatment.

Partner Management

All male sex partners who have had contact with a woman with pelvic inflammatory disease during the 60 days preceding onset of the pelvic inflammatory disease symptoms should be examined, tested, and presumptively treated for gonorrhea and chlamydia. If a patient’s last sexual intercourse was more than 60 days before onset of symptoms or diagnosis, the patient’s most recent sex partner should be treated. Expedited partner therapy may be utilized as detailed in the chlamydia module. Such evaluation and treatment are imperative because of the risk for reinfection and the strong likelihood of gonococcal or chlamydial infection in the sex partner. Patients (and ideally partners) should be counseled that:

- Male partners of women who have pelvic inflammatory disease caused by C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae are often asymptomatic.

- Sex partners of women with pelvic inflammatory disease should be treated empirically with regimens effective against both C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae, regardless of the apparent etiology of pelvic inflammatory disease or pathogens isolated from the infected woman.

- Group A streptococcal salpingitis in a prepubertal girl. Brown-Harrison MC, Christenson JC, Harrison AM, Matlak ME. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1995 Oct; 34(10):556-8.

- Tubo-ovarian abscess in a sexually inactive adolescent patient. Arda IS, Ergeneli M, Coskun M, Hicsonmez A. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Feb; 14(1):70-2.

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID). 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pid.htm

- Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, et al. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:400–5.

- Brunham RC, Gottlieb SL, Paavonen J. Pelvic inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2039-48.

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. https://www.std.uw.edu/go/syndrome-based/pelvic-inflammatory-disease/core-concept/all

- Sutton MY, Sternberg M, Zaidi A, St Louis ME, Markowitz LE. Trends in pelvic inflammatory disease hospital discharges and ambulatory visits, United States, 1985-2001. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:778-84.

- Kreisel K, Torrone E, Bernstein K, Hong J, Gorwitz R. Prevalence of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Sexually Experienced Women of Reproductive Age – United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:80-3.

- Bohm MK, Newman L, Satterwhite CL, Tao G, Weinstock HS. Pelvic inflammatory disease among privately insured women, United States, 2001-2005. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:131-6.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2015. STDs in women and infants. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016.

- Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Aral SO. Correlates of self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease treatment in sexually experienced reproductive-aged women in the United States, 1995 and 2006-2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:413-8.

- Ross JD, Hughes G. Why is the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease falling? BMJ. 2014;348:g1538.

- Scholes D, Satterwhite CL, Yu O, Fine D, Weinstock H, Berman S. Long-term trends in Chlamydia trachomatis infections and related outcomes in a U.S. managed care population. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:81-8.

- Jenkins CS, Williams SR, Schmidt GE. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa: A review of literature, discussion of clinical significance and consideration of patient management. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:599–607.

- Chawla N, Kudesia S, Azad S, Singhal M. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa. Ind J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:434–35.

- Chiari H. Zur Pathologischen anatomie des Eileit. Z Heilkd. 1887;8:457–64.

- Green LK, Kott ML. Histopathologic findings in ectopic tubal pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1989;8:255–62.

- Creasy JL, Clark RL, Cuttino JT, Groff TR. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa: Radiologic and clinical corelates. Radiology. 1985;154:597–600.

- Bundey JG, Williams JD. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa with tumor formation resembling torsion of an ovarian cyst. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1963;70:519–22.

- Honore LH. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa in female infertility and ectopic tubal pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1978;29:164–68.

- Persaud Y. Etiology of tubal ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1970;36:257–63.

- Majumdar B, Henderson PH, Semple E. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa: A high risk for tubal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1983;62:73–78.

- Wheeler JE. In: Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 1982. Pathology of the fallopian tube; pp. 403–04.

- Homm RJ, Holtz G, Garvin AJ. Isthamic ectopic pregnancy and salpingitis isthmica nodosa. Fertile Steril. 1987;48:756–60.

- Karasick S, Karasick D, Schilling J. Salpingitis isthmicanodosa in female infertility. J Can Assoc Radiol. 1985;36:118–21

- Yaranal PJ, Hegde V. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(11):2581-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3879862/

- Hay PE, Kerry SR, Normansell R, et al. Which sexually active young female students are most at risk of pelvic inflammatory disease? A prospective study. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92:63-6.

- Washington AE, Aral SO, Wølner-Hanssen P, Grimes DA, Holmes KK. Assessing risk for pelvic inflammatory disease and its sequelae. JAMA. 1991;266:2581-6.

- Ness RB, Kip KE, Hillier SL, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:585-90.

- Carr S, Espey E. Intrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:S22-8.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Madden T, Peipert JF. Positive Testing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis and the Risk of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in IUD Users. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:354-9.

- Eschenbach DA, Wölner-Hanssen P, Hawes SE, Pavletic A, Paavonen J, Holmes KK. Acute pelvic inflammatory disease: associations of clinical and laboratory findings with laparoscopic findings. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:184-92.

- Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Meyn LA, Amortegui AJ, Sweet RL. Subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:37-43.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(No. RR-3):1-137.

- Rosen M, Breitkopf D, Waud K. Tubo-ovarian abscess management options for women who desire fertility. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64:681-9.

- Peter NG, Clark LR, Jaeger JR. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome: a diagnosis to consider in women with right upper quadrant pain. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71:233-9.

- Chappell CA, Wiesenfeld HC. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of severe pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:893-903.

- Chayachinda C, Rekhawasin T. Reproductive outcomes of patients being hospitalised with pelvic inflammatory disease. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;:1-5.

- Weström L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, Hagdu A, Thompson SE. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility. A cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:185-92.

- Heinonen PK, Leinonen M. Fecundity and morbidity following acute pelvic inflammatory disease treated with doxycycline and metronidazole. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:284-8.

- Gaitan H, Angel E, Diaz R, et al. Accuracy of five different diagnostic techniques in mild-to-moderate pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2002;10:171–80.

- Bevan CD, Johal BJ, Mumtaz G, et al. Clinical, laparoscopic and microbiological findings in acute salpingitis: report on a United Kingdom cohort. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102:407–14.

- Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Meyn LA, et al. Subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:37–43.

- Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: results from the Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:929–37.

- Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: results from the Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Randomized Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:929-37.

- Walker CK, Wiesenfeld HC. Antibiotic therapy for acute pelvic inflammatory disease: the 2006 CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2007;28[Supp 1]:S29–36

- Bevan CD, Ridgway GL, Rothermel CD. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin as monotherapy or combined with metronidazole compared with two standard multidrug regimens for the treatment of acute pelvic inflammatory disease. J Int Med Res. 2003;31:45-54.

- Savaris RF, Teixeira LM, Torres TG, Edelweiss MI, Moncada J, Schachter J. Comparing ceftriaxone plus azithromycin or doxycycline for pelvic inflammatory disease: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:53-60.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. Pelvic inflammatory disease (pelvic inflammatory disease). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(No. RR-3):1-137.

- Mugo NR, Kiehlbauch JA, Nguti R, et al. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection on treatment outcome of acute salpingitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:807-12.

- McNeeley SG, Hendrix SL, Mazzoni MM, Kmak DC, Ransom SB. Medically sound, cost-effective treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1272-8.

- Reed SD, Landers DV, Sweet RL. Antibiotic treatment of tuboovarian abscess: comparison of broad-spectrum beta-lactam agents versus clindamycin-containing regimens. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1556-61.