Shoulder impingement

Shoulder impingement also called rotator cuff tendinitis, shoulder impingement syndrome, shoulder bursitis or subacromial bursitis, is one of the most common physical complaints is shoulder pain. Shoulder impingement occurs when there is inflammation of the rotator cuff tendons and the bursa around them. Shoulder impingement syndrome is usually a combination of the tendons becoming inflammed (tendonitis) and the bursa becoming inflammed (bursitis).

Shoulder impingement syndrome can occur secondary to direct blows to the shoulder, poor throwing mechanics in overhead sports, or from falls on an outstretched arm 1.

Your shoulder is made up of several joints combined with tendons and muscles that allow a great range of motion in your arm. Because so many different structures make up the shoulder, it is vulnerable to many different problems. The rotator cuff is a common source of pain in the shoulder.

Your rotator cuff is a group of muscles around your shoulder joint. They are very important as these muscles play an essential role in moving your shoulder in all directions, especially when lifting your hand above your head and rotating your shoulder.

They also have the important function of keeping your shoulder joint in place. Without them, the ball of your shoulder joint, would not sit or function properly in the socket of your shoulder joint.

A bursa is a fluid-filled c that acts as a cushion between tendons, bones, and skin. There are numerous bursae around the shoulder, but the most important one is called the ‘subacromial bursae’. It’s located above your shoulder joint and rotator cuff muscles, and protects them from rubbing on the bone above called the ‘acromion’.

Shoulder pain can be the result of:

- Tendinitis. The rotator cuff tendons can be irritated or damaged.

- Bursitis. The bursa can become inflamed and swell with more fluid causing pain.

- Impingement. When you raise your arm to shoulder height, the space between the acromion and rotator cuff narrows. The acromion can rub against (or “impinge” on) the tendon and the bursa, causing irritation and pain.

Shoulder anatomy

Your shoulder is a complex joint that is capable of more motion than any other joint in your body. It is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

Your arm is kept in your shoulder socket by your rotator cuff. These muscles and tendons form a covering around the head of your upper arm bone and attach it to your shoulder blade.

There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa allows the rotator cuff tendons to glide freely when you move your arm.

The shoulder region includes the glenohumeral joint, the acromioclavicular joint, the sternoclavicular joint and the scapulothoracic articulation (Figure 1). The glenohumeral joint capsule consists of a fibrous capsule, ligaments and the glenoid labrum. Because of its lack of bony stability, the glenohumeral joint is the most commonly dislocated major joint in the body. Glenohumeral stability is due to a combination of ligamentous and capsular constraints, surrounding musculature and the glenoid labrum. Static joint stability is provided by the joint surfaces and the capsulolabral complex, and dynamic stability by the rotator cuff muscles and the scapular rotators (trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids and levator scapulae).

Scapular stability collectively involves the trapezius, serratus anterior and rhomboid muscles. The levator scapular and upper trapezius muscles support posture; the trapezius and the serratus anterior muscles help rotate the scapula upward, and the trapezius and the rhomboids aid scapular retraction.

Ball and socket. The head of your upper arm bone fits into a rounded socket in your shoulder blade. This socket is called the glenoid. A slippery tissue called articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and the socket. It creates a smooth, frictionless surface that helps the bones glide easily across each other.

The glenoid is ringed by strong fibrous cartilage called the labrum. The labrum forms a gasket around the socket, adds stability, and cushions the joint.

Shoulder capsule. The joint is surrounded by bands of tissue called ligaments. They form a capsule that holds the joint together. The undersurface of the capsule is lined by a thin membrane called the synovium. It produces synovial fluid that lubricates the shoulder joint.

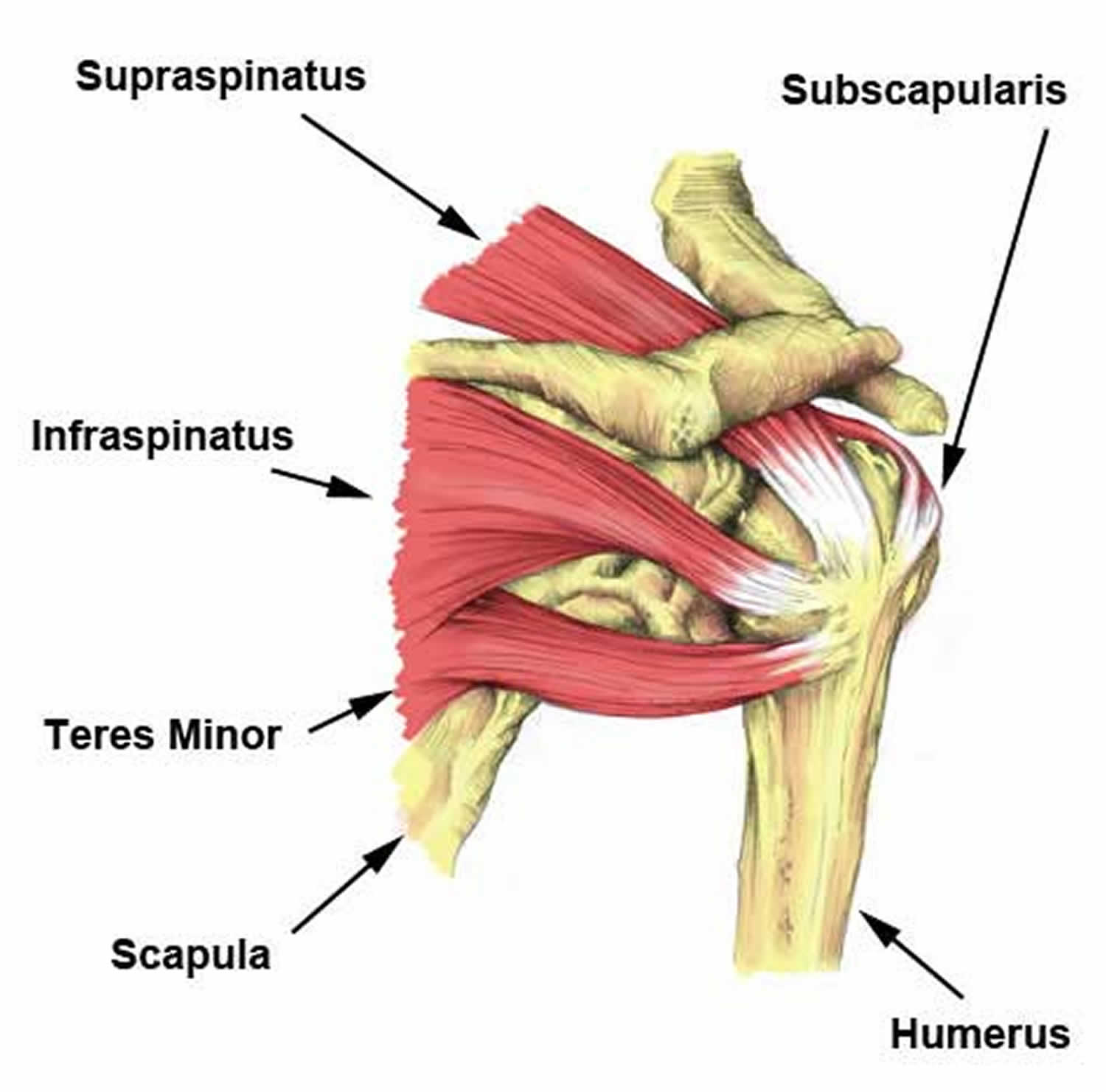

Rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is composed of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis (Figure 2). Four tendons surround the shoulder capsule and help keep your arm bone centered in your shoulder socket. This thick tendon material is called the rotator cuff. The cuff covers the head of the humerus and attaches it to your shoulder blade. The subscapularis facilitates internal rotation, and the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles assist in external rotation. The rotator cuff muscles depress the humeral head against the glenoid. With a poorly functioning (torn) rotator cuff, the humeral head can migrate upward within the joint because of an opposed action of the deltoid muscle.

Bursa. There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa helps the rotator cuff tendons glide smoothly when you move your arm.

Figure 1. Shoulder anatomy

Figure 2. Rotator cuff muscles and tendons

Shoulder impingement causes

Common causes of shoulder impingement include:

- Normal wear and tear with age.

- Repetitive stress. Repetitive overhead movement of your arms can stress your rotator cuff muscles and tendons, causing inflammation and eventually tearing. This occurs often in athletes and people in the building trades, such as painters and carpenters.

- Falls. Using your arm to break a fall or falling on your arm can bruise or tear a rotator cuff tendon or muscle.

Shoulder impingement pain is common in both young athletes and middle-aged people. Young athletes who use their arms overhead for swimming, baseball, and tennis are particularly vulnerable. Those who do repetitive lifting or overhead activities using the arm, such as paper hanging, construction, or painting are also susceptible.

Pain may also develop as the result of a minor injury. Sometimes, it occurs with no apparent cause.

Shoulder impingement pathophysiology

Overuse or repetitive microtrauma sustained in the overhead position may contribute to impingement and rotator cuff pathology. Shoulder pain and rotator cuff disease are common in athletes involved in sports requiring repetitive overhead arm motion (eg, swimming, baseball, volleyball, tennis).

Secondary impingement often is attributed to impingement, which seldom is mechanical in nature in young athletes. Rotator cuff disease in this population may be related to subtle instability, and, therefore, may be secondary to such factors as eccentric overload, muscle imbalance, glenohumeral instability, or labral lesions. This has led to the concept of secondary impingement, which is defined as rotator cuff impingement that occurs secondary to a functional decrease in the supraspinatus outlet space due to underlying instability of the glenohumeral joint.

Secondary impingement may be the most common cause in young athletes who frequently place large, repetitive overhead stresses on the static and dynamic glenohumeral stabilizers, resulting in microtrauma and attenuation of the glenohumeral ligamentous structures, which leads to subclinical glenohumeral instability. Such instability places increased stress on the dynamic stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint, including the rotator cuff tendons.

These increased demands may lead to rotator cuff pathology (eg, partial tearing, tendonitis). Furthermore, as the rotator cuff muscles fatigue, the humeral head translates anteriorly and superiorly, impinging upon the coracoacromial arch. This leads to rotator cuff inflammation. In these patients, treatment should address underlying instability.

The concept of glenoid impingement has been advanced as an explanation for partial-thickness tears in throwing athletes, particularly those involving the articular surface of the rotator cuff tendon. Such tears may occur in the presence of instability due to increased tensile stresses on the rotator cuff tendon from abnormal motion of the glenohumeral joint or increased forces on the rotator cuff necessary to stabilize the shoulder.

Arthroscopic studies of these patients note impingement between the posterior superior edge of the glenoid and the insertion of the rotator cuff tendon with the arm placed in the throwing position (abducted and externally rotated). Lesions were noted along the area of impingement at the posterior aspect of the glenoid labrum and articular surface of the rotator cuff. This concept is believed to occur most commonly in throwing athletes and must be considered when assessing for impingement.

Acute rotator cuff tendonitis

Acutely, rotator cuff tendonitis afflicts athletes at all levels of competition. Acute injuries often occur secondary to direct trauma to the shoulder in contact sports, poor throwing mechanics in overhead sports (i.e., baseball, javelin throwers), or from falls on an outstretched arm 1.

Chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy

Chronically, rotator cuff tendinopathy can occur secondary to a variety of proposed mechanisms:

Extrinsic compression

The extrinsic theory of mechanical impingement and pathologic contact between the undersurface of the acromion and the rotator cuff results in repetitive injury to the cuff. rotator cuff tendinopathy results in weakened areas of the cuff, eventually resulting in partial rotator cuff tears and/or full-thickness rotator cuff tears. The mechanical compression can occur secondary to a degenerative bursa, acromial spurring, and predisposing acromial morphologies (i.e., the hooked-type acromion). Theories were popularized and modified by Watson-Jones, Neer, and Bigliani 2.

Intrinsic mechanisms

Several theories exist to support intrinsic degeneration of the cuff as the primary source of shoulder impingement. In general, the intrinsic degenerative theories cite that cuff degeneration eventually compromises the overall stability of the glenohumeral joint. Once compromised, the humeral head migrates superiorly, and the subacromial space decreases in size. Thus, the cuff becomes susceptible to secondary extrinsic compressive forces, ultimately leading to cuff degeneration, tendinopathy, and tearing 3.

- Vascular changes – Advocates for intrinsic degenerative theories cite focal vascular adaptations that occur secondary to age-related changes and intrinsic cuff failure from repetitive eccentric forces directly experienced by the cuff itself. Lohr et al. initially demonstrated a distal area of the SS tendon on the articular side that lacks blood vessel supply 1 cm proximal to its insertional footprint 4. Rudzki et al. 5 demonstrated an age-dependent manner of increasing hypovascular regions in these distal cuff regions as well. Controversy proposed by other studies, however, supports that the attritional areas develop secondary to the preceding impingement mechanisms. Subsequently, external impingement leads to blood vessel damage, ensuing ischemia, tenocyte apoptosis, gross tendinopathy, and attritional cuff damage 2. Furthermore, many studies cite increased vascularity in focal areas of the cuff, and the hypervascularity has been associated with age-related changes, tendinopathy, and partial rotator cuff tears and/or full-thickness rotator cuff tears 6.

- Age, sex, and genetics – Histologically, age-related rotator cuff changes include collagen fiber disorientation and myxoid degeneration 7. The literature favors increasing frequencies of rotator cuff abnormalities with increasing age. The frequency increases from 5% to 10% in patients younger than 20 years of age, to 30% to 35% in those in their sixth and seventh decades of life, topping out at 60% to 65% in patients over 80 years of age 8.

- Tensile forces – A study by Budoff et al. 9 proposed that the primary mode of failure of the cuff occurs intrinsically within the cuff itself as it repeatedly withstands significant eccentric tensile forces during physical activity.

Risk factors for shoulder impingement syndrome

- Age

- Repetitive Overhead Activities

- Shape of a shoulder bone called the ‘acromion’

Shoulder impingement syndrome prevention

Primary prevention should be considered an integral part in the treatment of impingement syndrome. Education of patients at risk can do much to circumvent the development of impingement syndrome. Athletes, particularly those involved in throwing and overhead sports, and laborers with repetitive shoulder stress should be instructed in proper warm-up techniques, specific strengthening techniques, and have a good understanding of the warning signs of early impingement.

Shoulder impingement stages

In 1972, Neer 10 first introduced the concept of rotator cuff impingement to the literature, stating that it results from mechanical impingement of the rotator cuff tendon beneath the anteroinferior portion of the acromion, especially when the shoulder is placed in the forward-flexed and internally rotated position.

Neer describes the following 3 stages in the spectrum of rotator cuff impingement:

- Stage 1, commonly affecting patients younger than 25 years, is depicted by acute inflammation, edema, and hemorrhage in the rotator cuff. This stage usually is reversible with nonoperative treatment.

- Stage 2 usually affects patients aged 25-40 years, resulting as a continuum of stage 1. The rotator cuff tendon progresses to fibrosis and tendonitis, which commonly does not respond to conservative treatment and requires operative intervention.

- Stage 3 commonly affects patients older than 40 years. As this condition progresses, it may lead to mechanical disruption of the rotator cuff tendon and to changes in the coracoacromial arch with osteophytosis along the anterior acromion. Surgical l anterior acromioplasty and rotator cuff repair is commonly required.

In all Neer stages, the cause is impingement of the rotator cuff tendons under the acromion and a rigid coracoacromial arch, eventually leading to degeneration and tearing of the rotator cuff tendon.

Although rotator cuff tears are more common in the older population, impingement and rotator cuff disease are frequently seen in the repetitive overhead athlete. The increased forces and repetitive overhead motions can cause attritional changes in the distal part of the rotator cuff tendon, which is at risk due to poor blood supply. Impingement syndrome and rotator cuff disease affect athletes at a younger age compared with the general population.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the imaging study of choice for evaluation of shoulder pathology. In general, conservative measures for shoulder impingement syndrome are applied for at least 3-6 months or longer if the individual is improving, which is usually the case in 60-90% of patients. If the patient remains significantly disabled and has no improvement after 3 months of conservative treatment, the clinician must seek further diagnostic work-up, as well as reconsider other etiologies or refer the person for surgical evaluation.

Shoulder impingement signs and symptoms

Shoulder impingement pain commonly causes local swelling and tenderness in the front of the shoulder. You may have pain and stiffness when you lift your arm. There may also be pain when the arm is lowered from an elevated position.

Beginning symptoms may be mild. Patients frequently do not seek treatment at an early stage. These symptoms may include:

- Minor pain that is present both with activity and at rest

- Pain radiating from the front of the shoulder to the side of the arm

- Sudden pain with lifting and reaching movements

- Athletes in overhead sports may have pain when throwing or serving a tennis ball

As the problem progresses, the symptoms increase:

- Pain while sleeping at night

- Loss of strength and motion

- Difficulty doing activities that place the arm behind the back, such as buttoning or zippering

If the pain comes on suddenly, the shoulder may be severely tender. All movement may be limited and painful.

Shoulder impingement complications

Shoulder impingement pain can take a long time to get better. It can also progress to tears of your rotator cuff tendons, perhaps leading to long term permanent weakness. Other complications may include progression to adhesive capsulitis, cuff tear arthropathy, and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Complications also may result from surgery, injection, physical therapy, or medication.

Shoulder impingement diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of shoulder impingement syndrome can usually be accomplished with a thorough physical exam by your doctor.

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your shoulder. He or she will check to see whether it is tender in any area or whether there is a deformity. To measure the range of motion of your shoulder, your doctor will have you move your arm in several different directions. He or she will also test your arm strength.

Your doctor will check for other problems with your shoulder joint. He or she may also examine your neck to make sure that the pain is not coming from a “pinched nerve,” and to rule out other conditions, such as arthritis.

Shoulder exam

Specifically, rotator cuff strength and/or pathology can be assessed via the following examinations:

1. Supraspinatus

- Jobe’s test: a positive test is pain/weakness with resisted downward pressure while the patient’s shoulder is at 90 degrees of forward flexion and abduction in the scapular plane with the thumb pointing toward the floor.

- Drop arm test: the patient’s shoulder is brought into a position of 90 degrees of shoulder abduction in the scapular plane. The examiner initially supports the limb and then instructs the patient to slowly adduct the arm to the side of the body. A positive test includes the patient’s inability to maintain the abducted position of the shoulder and/or an inability to adduct the arm to the side of the trunk in a controlled manner.

2. Infraspinatus

- Strength testing is performed while the shoulder is positioned against the side of the trunk, the elbow is flexed to 90 degrees, and the patient is asked to externally rotate (external rotation) the arm while the examiner resists this movement.

- External rotation lag sign: the examiner positions the patient’s shoulder in the same position, and while holding the wrist, the arm is brought into maximum external rotation. The test is positive if the patient’s shoulder drifts into internal rotation once the examiner removes the supportive external rotation force at the wrist.

3. Teres Minor

- Strength testing is performed while the shoulder positioned at 90 degrees of abduction and the elbow is also flexed to 90 degrees. Teres minor is best isolated for strength testing in this position while external rotation is resisted by the examiner.

- Hornblower’s sign: the examiner positions the shoulder in the same position and maximally external rotations the shoulder under support. A positive test occurs when the patient is unable to hold this position, and the arm drifts into internal rotation once the examiner removes the supportive external rotation force.

4. Subscapularis

- Internal rotation lag sign: the examiner passively brings the patient’s shoulder behind the trunk (about 20 degrees of extension) with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. The examiner passively internal rotations the shoulder by lifting the dorsum of the handoff of the patient’s back while supporting the elbow and wrist. A positive test occurs when the patient is unable to maintain this position once the examiner releases support at the wrist (i.e., the arm is not maintained in internal rotation, and the dorsum of the hand drifts toward the back).

- Passive external rotation range of motion (ROM): a partial or complete tear of the subscapularis (SubSc) can manifest as an increase in passive external rotation compared to the contralateral shoulder.

- Lift-off test: more sensitive/specific for lower subscapularis pathology. In the same position as the internal rotation lag sign position, the examiner places the patient’s dorsum of the hand against the lower back and then resists the patient’s ability to lift the dorsum of the hand away from the lower back.

- Belly press: more sensitive/specific for upper subscapularis pathology. The examiner has the patient’s arm at 90 degrees of elbow flexion, and internal rotation testing is performed by the patient pressing the palm of his/her hand against the belly, bringing the elbow in front of the plane of the trunk. The elbow is initially supported by the examiner, and a positive test occurs if the elbow is not maintained in this position upon the examiner removing the supportive force.

5. External impingement

- Neer impingement sign: positive if the patient reports pain with passive shoulder forward flexion beyond 90 degrees.

- Neer impingement test: positive test occurs after a subacromial injection is given by the examiner and the patient reports improved symptoms upon repeating the forced passive forward flexion beyond 90 degrees.

- Hawkins test: positive test occurs with the examiner passively positioning the shoulder and elbow at 90 degrees of flexion in front of the body; the patient will report pain when the examiner passively internal rotation’s the shoulder.

6. Internal impingement

Internal impingement test: the patient is placed in a supine position and the shoulder is brought into terminal abduction and external rotation; a positive test consists of the reproduction of the patient’s pain.

Imaging tests

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

- X-rays. Because x-rays do not show the soft tissues of your shoulder like the rotator cuff, plain x-rays of a shoulder with rotator cuff pain are usually normal or may show a small bone spur. A special x-ray view, called an “outlet view,” sometimes will show a small bone spur on the front edge of the acromion.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is the best but expensive test for rotator cuff tears and shoulder impingement. It is over 95% accurate. MRI studies can create better images of soft tissues like the rotator cuff tendons. They can show fluid or inflammation in the bursa and rotator cuff. In some cases, partial tearing of the rotator cuff will be seen.

- Ultrasound. Ultrasound is a good test to look for shoulder bursitis and rotator cuff tears. However, it is not perfect, with studies showing the accuracy can range from 60- 90%

Shoulder impingement treatment

The goal of shoulder impingement syndrome treatment is to reduce pain and restore function. In planning your treatment, your doctor will consider your age, activity level, and general health.

Nonsurgical treatment

In most cases, initial treatment is nonsurgical. Although nonsurgical treatment may take several weeks to months, many patients experience a gradual improvement and return to function.

- Rest. Your doctor may suggest rest and activity modification, such as avoiding overhead activities.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIDs). Drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen reduce pain and swelling.

- Physical therapy. A physical therapist will initially focus on restoring normal motion to your shoulder. Stretching exercises to improve range of motion are very helpful. If you have difficulty reaching behind your back, you may have developed tightness of the posterior capsule of the shoulder (capsule refers to the inner lining of the shoulder and posterior refers to the back of the shoulder). Specific stretching of the posterior capsule can be very effective in relieving pain in the shoulder.

Once your pain is improving, your therapist can start you on a strengthening program for the rotator cuff muscles.

- Steroid injection. If rest, medications, and physical therapy do not relieve your pain, an injection of a local anesthetic and a cortisone preparation may be helpful. Cortisone is a very effective anti-inflammatory medicine. Injecting it into the bursa beneath the acromion can relieve pain.

Shoulder impingement physical therapy

Physical therapy or physiotherapy is an essential part of the treatment of shoulder impingement. Your physiotherapist will help you strengthen the muscles of the rotator cuff, advise you movements to avoid and help you regain your flexibility.

If the pain persists or if movement is not possible because of severe pain, a steroid injection may reduce pain and inflammation enough to allow effective physiotherapy.

A physical therapist can teach you range-of-motion exercises to help recover as much mobility in your shoulder as possible. Your commitment to doing these exercises is important to optimize recovery of your mobility.

Specific exercises will help restore motion. These may be under the supervision of a physical therapist or via a home program. Therapy includes stretching or range of motion exercises for the shoulder. Sometimes heat is used to help loosen the shoulder up before the stretching exercises.. Below are examples of some of the exercises that might be recommended.

External rotation — passive stretch

Stand in a doorway and bend your affected arm 90 degrees to reach the doorjamb. Keep your hand in place and rotate your body as shown in the illustration (Figure 2). Hold for 30 seconds. Relax and repeat.

Figure 2. Frozen shoulder exercise – external rotation passive stretch

Forward flexion — supine position

Lie on your back with your legs straight. Use your unaffected arm to lift your affected arm overhead until you feel a gentle stretch. Hold for 15 seconds and slowly lower to start position. Relax and repeat.

Figure 3. Frozen shoulder exercise – forward flexion in supine position

Crossover arm stretch

Gently pull one arm across your chest just below your chin as far as possible without causing pain. Hold for 30 seconds. Relax and repeat.

Figure 4. Frozen shoulder exercise – crossover arm stretch

Surgical treatment

When nonsurgical treatment does not relieve pain, your doctor may recommend surgery.

The goal of surgery is to create more space for the rotator cuff. To do this, your doctor will remove the inflamed portion of the bursa. He or she may also perform an anterior acromioplasty, in which part of the acromion is removed. This is also known as a subacromial decompression. These procedures can be performed using either an arthroscopic or open technique.

Arthroscopic technique

In arthroscopy, thin surgical instruments are inserted into two or three small puncture wounds around your shoulder. Your doctor examines your shoulder through a fiberoptic scope connected to a television camera. He or she guides the small instruments using a video monitor, and removes bone and soft tissue. In most cases, the front edge of the acromion is removed along with some of the bursal tissue.

Your surgeon may also treat other conditions present in the shoulder at the time of surgery. These can include arthritis between the clavicle (collarbone) and the acromion (acromioclavicular arthritis), inflammation of the biceps tendon (biceps tendonitis), or a partial rotator cuff tear.

Open surgical technique

In open surgery, your doctor will make a small incision in the front of your shoulder. This allows your doctor to see the acromion and rotator cuff directly.

Rehabilitation

After surgery, your arm may be placed in a sling for a short period of time. This allows for early healing. As soon as your comfort allows, your doctor will remove the sling to begin exercise and use of the arm.

Your doctor will provide a rehabilitation program based on your needs and the findings at surgery. This will include exercises to regain range of motion of the shoulder and strength of the arm. It typically takes 2 to 4 months to achieve complete relief of pain, but it may take up to a year.

Return to play

Return to play is restricted until full pain-free range of motion (ROM) is restored, both rest and activity-related pain are eliminated, and provocative impingement signs are negative. Isokinetic strength testing must be 90% compared to the contralateral side. When the patient is symptom-free, resuming activities is gradual, first during practice to build up endurance while working on modified techniques/mechanics, and then in simulated game situations. The athlete should continue flexibility and strengthening exercises after returning to his/her sport to prevent recurrence.

Shoulder impingement prognosis

In general, prognosis for prompt and correct diagnosis and treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome is good and 60-90% of patients improve and are symptom-free with conservative treatment. Surgical outcomes are promising in patients who fail conservative therapy.

References- Weiss LJ, Wang D, Hendel M, Buzzerio P, Rodeo SA. Management of Rotator Cuff Injuries in the Elite Athlete. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018 Mar;11(1):102-112.

- Harrison AK, Flatow EL. Subacromial impingement syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011 Nov;19(11):701-8.

- Sambandam SN, Khanna V, Gul A, Mounasamy V. Rotator cuff tears: An evidence based approach. World J Orthop. 2015 Dec 18;6(11):902-18.

- Lohr JF, Uhthoff HK. The microvascular pattern of the supraspinatus tendon. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1990 May;(254):35-8.

- Rudzki JR, Adler RS, Warren RF, Kadrmas WR, Verma N, Pearle AD, Lyman S, Fealy S. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound characterization of the vascularity of the rotator cuff tendon: age- and activity-related changes in the intact asymptomatic rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008 Jan-Feb;17(1 Suppl):96S-100S.

- Buck FM, Grehn H, Hilbe M, Pfirrmann CW, Manzanell S, Hodler J. Magnetic resonance histologic correlation in rotator cuff tendons. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010 Jul;32(1):165-72.

- Longo UG, Franceschi F, Ruzzini L, Rabitti C, Morini S, Maffulli N, Forriol F, Denaro V. Light microscopic histology of supraspinatus tendon ruptures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007 Nov;15(11):1390-4.

- Gumina S, Candela V, Passaretti D, Latino G, Venditto T, Mariani L, Santilli V. The association between body fat and rotator cuff tear: the influence on rotator cuff tear sizes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014 Nov;23(11):1669-74.

- Budoff JE, Nirschl RP, Guidi EJ. Débridement of partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff without acromioplasty. Long-term follow-up and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998 May;80(5):733-48.

- Neer CS 2nd. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972 Jan. 54(1):41-50.