Sotos syndrome

Sotos syndrome also called Sotos sequence or cerebral gigantism, is a disorder characterized by a distinctive facial features, overgrowth in childhood, and learning disabilities or delayed development of mental and movement abilities 1. Characteristic facial features include a long, narrow face; a high forehead; flushed (reddened) cheeks; and a small, pointed chin. In addition, the outside corners of the eyes may point downward (down-slanting palpebral fissures). This facial appearance is most notable in early childhood. Affected infants and children tend to grow quickly; they are significantly taller than their siblings and peers and have an unusually large head. However, adult height is usually in the normal range.

People with Sotos syndrome often have intellectual disability, and most also have behavioral problems. Frequent behavioral issues include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), phobias, obsessions and compulsions, tantrums, and impulsive behaviors. Problems with speech and language are also common. Affected individuals often have a stutter, a monotone voice, and problems with sound production. Additionally, weak muscle tone (hypotonia) may delay other aspects of early development, particularly motor skills such as sitting and crawling.

Other signs and symptoms of Sotos syndrome can include an abnormal side-to-side curvature of the spine (scoliosis), seizures, heart or kidney defects, hearing loss, and problems with vision. Some infants with this disorder experience yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice) and poor feeding.

A small percentage of people with Sotos syndrome have developed cancer, most often in childhood, but no single form of cancer occurs most frequently with this condition. It remains uncertain whether Sotos syndrome increases the risk of specific types of cancer. If people with this disorder have an increased cancer risk, it is only slightly greater than that of the general population.

Sotos syndrome is usually caused by a mutation in the NSD1 (nuclear receptor-binding SET domain protein 1) gene and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. About 95% of cases are due to a new mutation in the affected person and occur sporadically (are not inherited) 1

Sotos syndrome is reported to occur in 1 in 10,000 to 14,000 newborns 1. Because many of the features of Sotos syndrome can be attributed to other conditions, many cases of Sotos syndrome are likely not properly diagnosed, so the true incidence may be closer to 1 in 5,000.

Sotos syndrome treatment: When clinical problems (e.g., cardiac anomalies, renal anomalies, scoliosis, or seizures) are identified, referral to the appropriate specialist is recommended. Referral to appropriate specialists for management of learning disability / speech delays and behavior problems; intervention is not recommended if the brain MRI shows ventricular dilatation without raised intracranial pressure.

Surveillance: Regular review by a general pediatrician for younger children, individuals with many medical complications, and families requiring more support than average; less frequent review of older children / teenagers and those individuals without many medical complications.

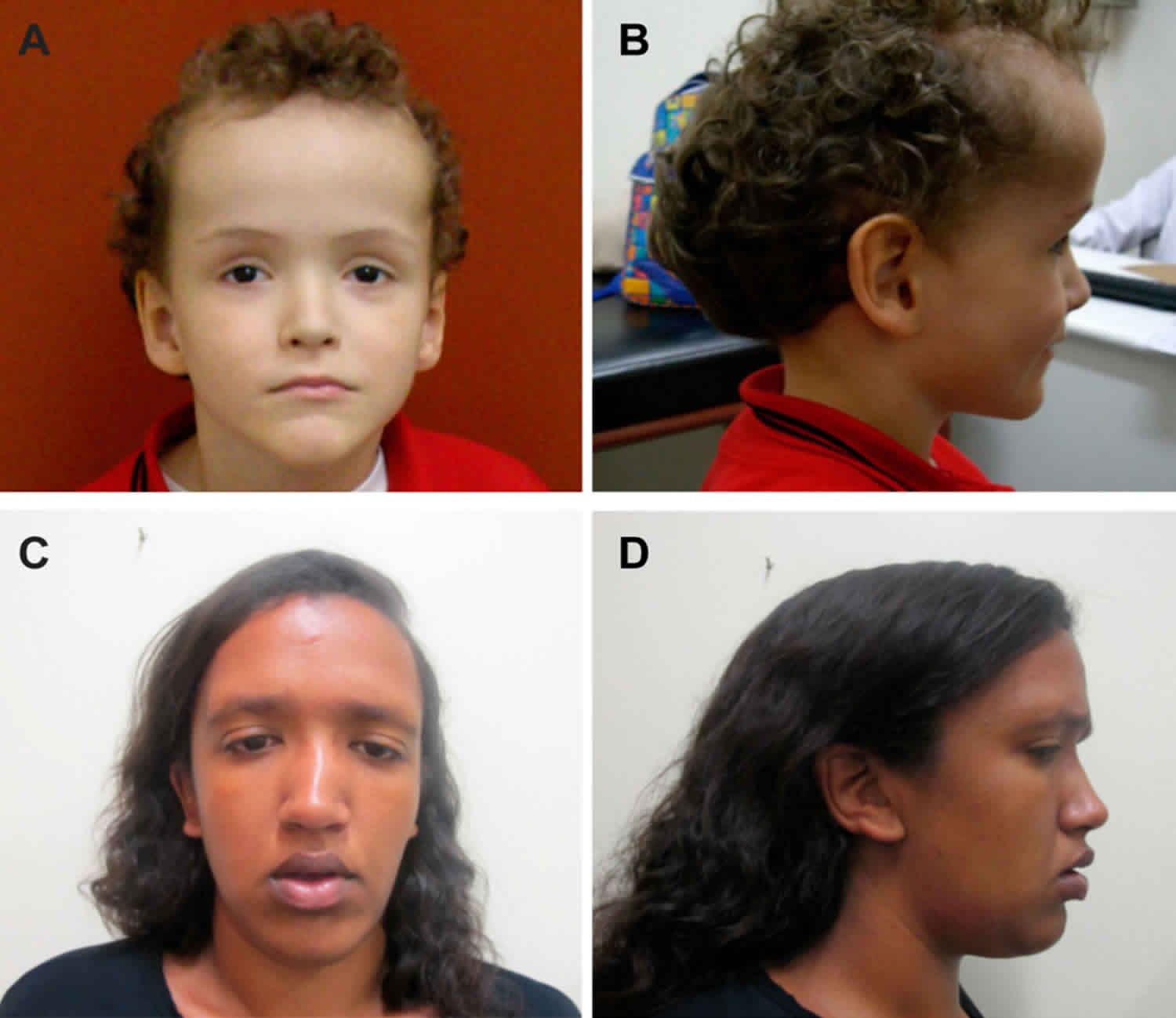

Figure 1. Sotos syndrome

Footnote: Facial features in Sotos syndrome patients with NSD1 deletion (top) or mutation (bottom). Note the prominent forehead, downward slanting palpebral fissures, long face, and pointed chin.

[Source 2 ]Figure 2. Sotos syndrome

Footnote: General features in Brazilian Sotos syndrome patients with NSD1 mutations. (A,B) Facial features at age eight years with macrocephaly, prominent forehead, ocular hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures and pointed chin; and (C,D) facial features at age 21 years with macrocephaly, prominent forehead, ocular hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures and pointed chin.

[Source 3 ]Sotos syndrome causes

Mutations in the NSD1 (nuclear receptor-binding SET domain protein 1) gene are the primary cause of Sotos syndrome, accounting for up to 90 percent of cases. Other genetic causes of this condition have not been identified.

The NSD1 gene provides instructions for making a protein that functions as a histone methyltransferase. Histone methyltransferases are enzymes that modify structural proteins called histones, which attach (bind) to DNA and give chromosomes their shape. By adding a molecule called a methyl group to histones (a process called methylation), histone methyltransferases regulate the activity of certain genes and can turn them on and off as needed. The NSD1 protein controls the activity of genes involved in normal growth and development, although most of these genes have not been identified.

Genetic changes involving the NSD1 gene prevent one copy of the gene from producing any functional protein. Research suggests that a reduced amount of NSD1 protein disrupts the normal activity of genes involved in growth and development. However, it remains unclear exactly how a shortage of this protein during development leads to overgrowth, learning disabilities, and the other features of Sotos syndrome.

A few years ago, mutations in the NFIX gene (nuclear factor I, X type) were identified in 5 patients with Sotos syndrome (Sotos syndrome 2) 4. In 2015, a loss-of-function mutation in the APC2 (adenomatous polyposis coli 2) gene was reported in 2 siblings with some neural features of Sotos syndrome including intellectual disability, abnormal brain structure, and typical facial features, but no other features such as bone or heart abnormalities (Sotos syndrome 3). The parents were blood relatives (consanguineous). The APC2 gene is specifically expressed in the nervous system, and is a crucial downstream gene of NSD1. In other words, mutations in the NSD1 gene affects the APC2 gene and results in the neural abnormalities.

Sotos syndrome inheritance pattern

About 95 percent of Sotos syndrome cases occur in people with no history of the disorder in their family. Most of these cases result from new (de novo) mutations involving the NSD1 gene.

About 5% of families have been described with more than one affected family member. These cases helped researchers determine that Sotos syndrome has an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. Autosomal dominant inheritance means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause Sotos syndrome.

If a parent of an affected person with an identified NSD1 mutation does not have any features of Sotos syndrome, that parent is very unlikely to have a mutation in the gene. This can be confirmed with genetic testing if the mutation has been identified in the child.

If a person with Sotos syndrome has children, each child has a 50% (1 in 2) chance to inherit the mutation. However, the specific features and severity can vary from one generation to the next, so it is not possible to predict how a child will be affected 5.

Sotos syndrome 3 is an autosomal recessive condition. Recessive genetic disorders occur when an individual inherits an abnormal variant of a gene from each parent. If an individual receives one normal gene and one abnormal variant gene for the disease, the person will be a carrier for the disease, but usually will not show symptoms. The risk for two carrier parents to both pass the abnormal variant gene and, therefore, have an affected child is 25% with each pregnancy. The risk to have a child who is a carrier, like the parents, is 50% with each pregnancy. The chance for a child to receive normal genes from both parents is 25%. The risk is the same for males and females.

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Is there a reason for an unaffected sibling of a person with Sotos syndrome to be tested?

To date, no NSD1 mutations have been identified in an unaffected parent or unaffected sibling of a person with Sotos syndrome caused by a mutation in the NSD1 gene. This means that Sotos syndrome appears to have full penetrance. It is assumed that every person with a mutation in the responsible gene will have features of the condition 5. Due to the fact that only 5% of affected people inherit Sotos syndrome from a parent and the condition is apparently fully penetrant, siblings confirmed to be unaffected may not need to be tested for the condition. However, the features and severity of Sotos syndrome can be variable. Therefore, people with questions about the underlying cause of Sotos syndrome in their family and genetic risks to themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional about genetic testing.

How can a condition be autosomal dominant if it is not inherited and not passed on to children?

The term ‘autosomal dominant’ means that having a disease-causing mutation in only one of the two copies of the responsible gene is sufficient to cause the condition. The term does not necessarily imply that the mutated gene must be inherited from an affected parent.

In many people with an autosomal dominant condition, the disease-causing mutation occurs sporadically for the first time in the affected person. This is called a de novo mutation. However, once a person has a mutation, they then have a 50% chance to pass it on to each of their children. For some conditions (such as Sotos syndrome), only a very small proportion of people inherit the condition from a parent; most cases result from new mutations in the gene in people with no family history of the condition. If the child of a person with an autosomal dominant condition does not inherit the mutated gene, they cannot pass the mutated gene to their offspring.

Some conditions greatly impair physical and/or intellectual abilities; others may shorten the lifespan so that affected people do not reach reproductive age. In these cases, it may be unlikely that an affected person would pass the mutated gene on to offspring. However, the condition is still considered autosomal dominant because having a mutation in only one copy of the responsible gene is sufficient to cause the condition.

Sotos syndrome symptoms

Sotos syndrome main clinical finding is prenatal and postnatal overgrowth. The growth velocity is particularly excessive in the first 3 to 4 years of life and subsequently proceeds at the normal rate, but in the high percentiles. The mean height is usually 2 to 3 years ahead of peers during childhood. The weight is usually appropriate for the height and the bone age is advanced mean by 2 to 4 years over chronological age, during childhood. Adult height usually exceeds the average of normal men or women. Some individuals may reach excessive adult heights; males of 193 cm to 203 cm (6 ft. 4 in. to 6 ft. 8 in.) and females up to 188 cm (6 ft. 2 in.) are known.

Cardinal features (present in ≥90% of persons with Sotos syndrome)

- Characteristic facial appearance

- Learning disability

- Overgrowth (height and/or head circumference ≥2 SD above mean)

Major features (present in 15%-89% of persons with Sotos syndrome)

- Behavioral problems – most notably autistic spectrum disorder

- Advanced bone age

- Cardiac anomalies

- Cranial MRI/CT abnormalities

- Joint hyperlaxity with or without pes planus

- Maternal preeclampsia

- Neonatal complications

- Renal anomalies

- Scoliosis

- Seizures

The craniofacial configuration is most characteristic, with a prominent forehead and receding forehead hairline in 96% of patients, dolichocephalic head, widely spaced eyes (hypertelorism), down slanting of the eye lids and folds (palpebral features), high narrow palate, pointed chin, a long narrow face and a head shape that is similar to an inverted pear. The typical facial features are most apparent in childhood. As the child matures, the chin becomes more prominent and square in shape. In adults, the craniofacial characteristics are less distinctive but the chin is prominent and the dolichocephalic and receding hairline (frontal bossing) remain.

Central nervous system manifestations are frequent. Delay in the attainment of milestones of development, walking and talking and in particular speech, is almost always present and clumsiness is frequent (60 to 80%), as is low muscle tone (hypotonia) and lax joints. Intellectual disability is present in 80 to 85% of the patients, with an average IQ of 72 and a range from 40 to borderline mild intellectual disability. Fifteen to 20% may have normal intelligence. Seizures may occur in 30% of those affected. Some brain abnormalities (enlarged ventricles) may occur.

Individuals with Sotos syndrome can also experience behavioral problems at all ages that can make it difficult for them to develop relationships with others.

Newborns often have jaundice, difficulty feeding and low muscle tone (hypotonia). Heart defects are present in about 8 to 35% of children with Sotos syndrome but are usually not severe. Abnormalities in the genital and/or urinary systems occur in about 20% of affected individuals. Other findings associated with Sotos syndrome include conductive hearing loss that may be associated with an increased frequency of upper respiratory infections, eye abnormalities such as crossed eyes (strabismus), and skeletal problems. A curved spine (scoliosis) is present in about 40% of those affected but is usually not severe enough to require bracing or surgery. Premature eruption of teeth occurs in 60 to 80%. Approximately 2.2 to 3.9% of patients develop tumors including sacrococcygeal teratoma, neuroblastoma, presacral ganglioma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Affected infants and children usually experience a delay in achieving certain developmental milestones (e.g., sitting, crawling, walking, etc.). They may not begin to walk until approximately 15 to 17 months of age. Affected children may also experience difficulty performing certain tasks requiring coordination (such as riding a bicycle or playing sports), fine motor skills (e.g., the ability to grasp small objects), and may demonstrate unusual clumsiness. Children with this disorder typically experience delays in attaining language skills. In many cases, affected children may not begin to speak until approximately two to three years of age.

Behavioral problems

A wide range of behavioral problems are common at all ages: autistic spectrum disorder, phobias, and aggression have been described 6. Often difficulty with peer group relationships is precipitated by large size, naiveté, and lack of awareness of social cues 7. These observations were confirmed in a study of individuals with a clinical diagnosis of Sotos syndrome (some with and some without an NSD1 pathogenic variant); it was additionally noted that attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is not common among individuals with Sotos syndrome 8

Advanced bone age

Bone age often reflects the accelerated growth velocity and is advanced in 75%-80% of prepubertal children. However, bone age interpretation is influenced by the “threshold” taken as significant, the method of assessment, subjective interpretative error, and the age at which the assessment is made.

Cardiac anomalies

About 20% of individuals have cardiac anomalies that range in severity from single, often self-limiting anomalies (including patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, and ventricular septal defect) to more severe, complex cardiac abnormalities. Two unrelated individuals with Sotos syndrome have been shown to have left ventricular non-compaction 9. Three adult patients with Sotos syndrome and aortic dilatation have been reported 10.

Cranial MRI/CT abnormalities are identified in the majority of individuals with Sotos syndrome and an NSD1 pathogenic variant.

Ventricular dilatation (particularly in the trigone region) is most frequently identified; other abnormalities include midline changes (hypoplasia or agenesis of the corpus callosum, mega cisterna magna, cavum septum pellucidum), cerebral atrophy, and small cerebellar vermis 11.

Joint hyperlaxity / pes planus

Joint laxity is reported in at least 20% of individuals with Sotos syndrome.

Maternal preeclampsia occurs in about 15% of pregnancies of children with Sotos syndrome.

Neonatal complications. Neonates may have jaundice (~65%), hypotonia (~75%), and poor feeding (~70%). These complications tend to resolve spontaneously, but in a small minority intervention is required.

Renal anomalies. About 15% of individuals with an NSD1 pathogenic variant have a renal anomaly; vesicoureteral reflux is the most common. Some individuals may have quiescent vesicoureteral reflux and may present in adulthood with renal impairment.

Scoliosis. Present in about 30% of affected individuals, scoliosis is rarely severe enough to require bracing or surgery.

Seizures. Approximately 25% of individuals with Sotos syndrome develop non-febrile seizures at some point in their lives and some require ongoing therapy. Absence, tonic-clonic, myoclonic, and partial complex seizures have all been reported.

Associated features

Tumors occur in approximately 3% of persons with Sotos syndrome. The broad range includes sacrococcygeal teratoma, neuroblastoma, presacral ganglioma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, small-cell lung cancer, and astrocytoma 12. De Boer and colleagues have characterized and reviewed these problems and compared persons with Sotos syndrome who have NSD1 pathogenic variants to those who do not 8..

Various other clinical features have been associated with Sotos syndrome. Some associated features, such as constipation and hearing problems caused by chronic otitis media, are common. The following features are seen in ≥2% and <15% of individuals with Sotos syndrome 13.:

- Astigmatism

- Cataract

- Cholesteatoma

- Conductive hearing loss

- Constipation

- Contractures

- Craniosynostosis

- Cryptorchidism

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Hemangioma

- Hemihypertrophy

- Hirschsprung’s disease

- Hydrocele

- Hypercalcemia

- Hypermetropia

- Hypodontia

- Hypoplastic nails

- Hypospadias

- Hypothyroidism

- Inguinal hernia

- Myopi

- Neonatal hypoglycemia

- Nystagmus

- Pectus excavatu

- Phimosis

- Skin hyperpigmentation

- Skin hypopigmentation

- Strabismus

- Subpleural blebs

- Talipes equinovarus

- Umbilical hernia

- Vertebral anomalies

- 2/3 toe syndactyly

Can the features of Sotos syndrome vary among affected people?

Yes. The features of Sotos syndrome can vary among affected people. At least 90% of affected people have the ‘cardinal’ features of the condition, which include a characteristic facial appearance, learning disability, and overgrowth. While the majority have some degree of intellectual impairment, this may range from having a mild learning disability (ultimately living independently and having a family) to a severe learning disability (being unable to live independently as an adult). Many other features may also occur in a smaller proportion of people and may also range in severity 5.

Sotos syndrome diagnosis

There is no biochemical marker for Sotos syndrome. The diagnosis is based on clinical grounds. The most characteristic manifestations are the craniofacial configuration, excessive growth, and developmental delay. The diagnosis of a patient with the typical craniofacial configuration and excessive growth can be made at the first site. The craniofacial configuration is the most distinctive, and only rarely (~ 1%), is not present. Ten percent of the children and adolescents may be below +2 SD in height and 10 or 15% of the patients may not have developmental delay. Advanced bone age may be present in 76 to 86% of the patients and is helpful but not specific. Brain abnormalities are present in 60 to 80% of patients, such as communicating hydrocephalous, and others, but are not diagnostic and are non-specific.

Based on the analysis of more than 266 individuals with an NSD1 pathogenic variant, the three cardinal features (facial appearance, learning disability, and overgrowth) were shown to occur in at least 90% of affected individuals 13.

Characteristic facial appearance (most easily recognizable between ages 1 and 6 years):

- Broad, prominent forehead with a dolichocephalic head shape

- Sparse frontotemporal hair

- Downslanting palpebral fissures

- Malar flushing

- Long narrow face (particularly bitemporal narrowing)

- Long chin

- Note: Facial shape is retained into adulthood; with time the chin becomes broader (squarer in shape).

Characteristic facial appearance. The facial gestalt is the most specific diagnostic criterion for Sotos syndrome, and also the one most open to observer error due to inexperience. The facial gestalt of Sotos syndrome is evident at birth, but becomes most recognizable between ages one and six years. The head is dolichocephalic and the forehead broad and prominent. Often the hair in the frontotemporal region is sparse. The palpebral fissures are usually downslanting. Malar flushing may be present. In childhood the jaw is narrow with a long chin; in adulthood the chin broadens 14. In older children and adults, the facial features, although still typical, can be more subtle 13.

Learning disability

- Early developmental delay

- Mild-to-severe intellectual impairment

Delay of early developmental milestones is very common and motor skills may appear particularly delayed because of a child’s large size, hypotonia, and poor coordination. The majority of individuals with Sotos syndrome have some degree of intellectual impairment. The spectrum is broad and ranges from a mild learning disability (affected individuals would be expected to live independently and have their own families) to a severe learning disability (affected individuals would be unlikely to live independently as adults). The level of intellectual impairment generally remains stable throughout life 6. The learning disability in children with Sotos syndrome is characterized by relative strength in verbal ability and visuospatial memory but relative weakness in nonverbal reasoning ability and quantitative reasoning 15.

Overgrowth

- Height and/or head circumference ≥2 SD above the mean (i.e., ~98th centile)

- Note: Height may normalize in adulthood.

- Macrocephaly usually present at all ages

Sotos syndrome is associated with overgrowth of prenatal onset. Delivery is typically at term. The average birth length approximates to the 98th centile and the average birth head circumference is between the 91st and 98th centiles. Average birth weight is within the normal range (50th-91st centile).

Before age ten years, affected children often demonstrate rapid linear growth. They are often described as being considerably taller than their peers. Approximately 90% of children have a height and/or head circumference at least 2 SD above the mean 13. However, growth is also influenced by parental heights and some individuals do not have growth parameters above the 98th centile 13.

Height may normalize in adulthood, but macrocephaly is usually present at all ages 6. Data on final adult height are scarce; however, in both men and women, the range of final adult height is broad 6.

The de Boer et al 16 study of auxologic data supports that of Agwu et al 17 and shows that individuals with an NSD1 pathogenic variant have an increased arm span / height ratio, decreased sitting/standing height ratio, and increased hand length. These data suggest that the increased height in Sotos syndrome is predominantly the result of an increase in limb length 16.

Establishing the diagnosis

The diagnosis can be confirmed by DNA studies by FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) analysis to detect microdeletions or MLPA (multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification), a simple and reliable method to detect chromosome 5q35 microdeletions and partial NSD1 gene deletions, which account for approximately 10-15% of the cases in western populations. DNA analysis by genome sequencing can determine the specific NSD1 gene mutations.

In patients without NSD1 gene mutations, genetic testing for mutations in NFIX and APC2 genes should be obtained.

Sotos syndrome treatment

The treatment of Sotos syndrome is directed toward the specific symptoms that are apparent in each individual. Treatment may require the coordinated efforts of a team of specialists. Pediatricians, pediatric endocrinologists, geneticists, neurologists, surgeons, speech pathologists, specialists who diagnose and treat skeletal disorders (orthopedists), physicians who diagnose and treat eye disorders (ophthalmologists), physical therapists, and/or other health care professionals may need to systematically and comprehensively plan an affected child’s treatment.

When a child is diagnosed with Sotos syndrome, a heart examination and kidney ultrasound should be performed and if abnormalities are identified, an appropriate specialist should be consulted. Children with Sotos syndrome should have a thorough examination every one to two years that includes a back exam for scoliosis, eye exam, blood pressure measurement, and a speech and language evaluation. Appropriate specialists should be consulted as needed.

Clinical evaluation should be conducted early in development and on a continuing basis to help confirm the presence and extent of developmental delay, psychomotor delay, and/or intellectual disability. Such evaluation and early intervention may help ensure that appropriate steps are taken to help affected individuals reach their highest potential. Special services that may be beneficial to affected children may include infant stimulation, special education, special social support, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and adaptive physical education.

A small percentage (2.2 to 3.9%) of individuals with Sotos syndrome may be more prone to developing certain benign tumors and malignancies than the general population. Owing to the low risk for these problems, that the age of onset or detection is from infancy to adulthood and the location variable (~1/3 intra-abdominal, 2/3 extra-abdominal), there is no recommended routine screening.

If brain MRI has been performed and ventricular dilatation demonstrated, shunting should not usually be necessary as the “arrested hydrocephalus” associated with Sotos syndrome is typically not obstructive and not associated with raised intracranial pressure. If raised intracranial pressure is suspected, investigation and management in consultation with neurologists and neurosurgeons would be appropriate.

To establish the extent of disease and needs in an individual diagnosed with Sotos syndrome, the following evaluations (if not performed as part of the evaluation that led to the diagnosis) are recommended 18:

- A thorough history to identify known features of Sotos syndrome: learning difficulties, cardiac and renal anomalies, seizures, and scoliosis

- Physical examination including cardiac auscultation, blood pressure measurement, and back examination for scoliosis

- Investigations to detect abnormalities before they result in significant morbidity or mortality:

- In children in whom the diagnosis has just been established, echocardiogram and renal ultrasound examination

- In adults in whom the diagnosis has just been established, renal ultrasound examination to evaluate for renal damage from quiescent chronic vesicoureteral reflux

- Referral for audiologic assessment. Conductive hearing loss may occur at an increased frequency in Sotos syndrome; thus, the threshold for referral should be low.

- Genetic counseling is recommended for affected individuals and their families.

Surveillance

Regular evaluation by a general pediatrician is recommended for younger children, individuals with many medical complications needing coordination of medical specialists, and families requiring more support than average 18.

The clinician may wish to evaluate older children, teenagers, and those individuals without many medical complications less frequently.

Table 1. Recommended surveillance for individuals with Sotos syndrome

| System/Concern | Evaluation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Evaluation by cardiologist | At clinical review |

| Echocardiogram |

| |

| Blood pressure check | At clinical review | |

| Skeletal | Examine spine for curvature. | At clinical review |

| Urinary tract | Urinalysis, urine culture for quiescent urine infection | At clinical review |

| Eyes | Ophthalmologic exam | Where there are concerns |

| Ears | Hearing test | Where there are concerns |

Footnote: Cancer screening is not recommended 19:

- The absolute risk of sacrococcygeal teratoma and neuroblastoma is low (~1%) 6. This level of risk does not warrant routine screening, particularly as screening for neuroblastoma has not been shown to decrease mortality and can lead to false positive results 20.

- Wilms tumor risk is not significantly increased and routine renal ultrasound examination is not indicated 21.

Developmental Delay / Intellectual Disability Management Issues

For difficulties with learning/behavior/speech that can be found in individuals with Sotos syndrome, the following information represents typical management recommendations for individuals with developmental delay / intellectual disability in the United States; standard recommendations may vary from country to country.

Ages 0-3 years

- Referral to an early intervention program is recommended for access to occupational, physical, speech, and feeding therapy. In the US, early intervention is a federally funded program available in all states.

Ages 3-5 years

- In the US, developmental preschool through the local public school district is recommended. Before placement, an evaluation is made to determine needed services and therapies and an individualized education plan (IEP) is developed.

Ages 5-21 years

- In the US, an individualized education plan (IEP) based on the individual’s level of function should be developed by the local public school district. Affected children are permitted to remain in the public school district until age 21.

- Discussion about transition plans including financial, vocation/employment, and medical arrangements should begin at age 12 years. Developmental pediatricians can provide assistance with transition to adulthood.

All ages

Consultation with a developmental pediatrician is recommended to ensure the involvement of appropriate community, state, and educational agencies and to support parents in maximizing quality of life.

Consideration of private supportive therapies based on the affected individual’s needs is recommended. Specific recommendations regarding type of therapy can be made by a developmental pediatrician.

In the US:

- Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA) enrollment is recommended. DDA is a public agency that provides services and support to qualified individuals. Eligibility differs by state but is typically determined by diagnosis and/or associated cognitive/adaptive disabilities.

- Families with limited income and resources may also qualify for supplemental security income (SSI) for their child with a disability.

Motor dysfunction

Gross motor dysfunction

- Physical therapy is recommended to maximize mobility and to reduce the risk for later-onset orthopedic complications (e.g., contractures, scoliosis, hip dislocation).

- Consider use of durable medical equipment as needed (e.g., wheelchairs, walkers, bath chairs, orthotics, adaptive strollers).

- For muscle tone abnormalities including hypertonia or dystonia, consider involving appropriate specialists to aid in management of baclofen, Botox®, anti-parkinsonian medications, or orthopedic procedures.

Fine motor dysfunction

Occupational therapy is recommended for difficulty with fine motor skills that affect adaptive function such as feeding, grooming, dressing, and writing.

Oral motor dysfunction. Assuming that the individual is safe to eat by mouth, feeding therapy – typically from an occupational or speech therapist – is recommended for affected individuals who have difficulty feeding due to poor oral motor control.

Communication issues. Consider evaluation for alternative means of communication (e.g., Augmentative and Alternative Communication [AAC]) for individuals who have expressive language difficulties.

Social/Behavioral Concerns

Children may qualify for and benefit from interventions used in treatment of autism spectrum disorder, including applied behavior analysis (ABA). Applied behavior analysis therapy is targeted to the individual child’s behavioral, social, and adaptive strengths and weaknesses and is typically performed one on one with a board-certified behavior analyst.

Consultation with a developmental pediatrician may be helpful in guiding parents through appropriate behavioral management strategies or providing prescription medications when necessary.

Concerns about serious aggressive or destructive behavior can be addressed by a pediatric psychiatrist.

Sotos syndrome prognosis

Sotos syndrome is not a life-threatening disorder and patients may have a normal life expectancy. The initial abnormalities of Sotos syndrome usually resolve as the growth rate becomes normal after the first few years of life. Developmental delays may improve in the school-age years, and adults with Sotos syndrome are likely to be within the normal range for intellect and height. However, coordination problems may persist into adulthood.

References- Sotos syndrome. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/sotos-syndrome

- Rio M, Clech L, Amiel J, et al. Spectrum of NSD1 mutations in Sotos and Weaver syndromes. J Med Genet. 2003;40(6):436–440. doi:10.1136/jmg.40.6.436 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1735492/pdf/v040p00436.pdf

- Steric Clash in the SET Domain of Histone Methyltransferase NSD1 as a Cause of Sotos Syndrome and Its Genetic Heterogeneity in a Brazilian Cohort Genes 2016, 7(11), 96; https://doi.org/10.3390/genes7110096

- Sotos syndrome. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/sotos-syndrome/

- Tatton-Brown K, Cole TRP, Rahman N. Sotos Syndrome. 2004 Dec 17 [Updated 2019 Aug 1]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1479

- Foster A, Zachariou A, Loveday C, Ashraf T, Blair E, Clayton-Smith J, Dorkins H, Fryer A, Gener B, Goudie D, Henderson A, Irving M, Joss S, Keeley V, Lahiri N, Lynch SA, Mansour S, McCann E, Morton J, Motton N, Murray A, Riches K, Shears D, Stark Z, Thompson E, Vogt J, Wright M, Cole T, Tatton-Brown K. The phenotype of Sotos syndrome in adulthood: a review of 44 individuals. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2019. Epub ahead of print.

- Finegan JK, Cole TR, Kingwell E, Smith ML, Smith M, Sitarenios G. Language and behavior in children with Sotos syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:1307–15.

- de Boer L, Roder I, Wit JM. Psychosocial, cognitive, and motor functioning in patients with suspected Sotos syndrome: a comparison between patients with and without NSD1 gene alterations. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48:582–8.

- Martinez HR, Belmont JW, Craigen WJ, Taylor MD, Jefferies JL. Left ventricular noncompaction in Sotos syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1115–8.

- Hood RL, McGillivray G, Hunter MF, Roberston SP, Bulman DE, Boycott KM, Stark Z, et al. Severe connective tissue laxity including aortic dilatation in Sotos syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A:531–5.

- Waggoner DJ, Raca G, Welch K, Dempsey M, Anderes E, Ostrovnaya I, Alkhateeb A, Kamimura J, Matsumoto N, Schaeffer GB, Martin CL, Das S. NSD1 analysis for Sotos syndrome: insights and perspectives from the clinical laboratory. Genet Med. 2005;7:524–33.

- Theodoulou E, Baborie A, Jenkinson MD. Low grade glioma in an adult patient with Sotos syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:413–5.

- Tatton-Brown K, Douglas J, Coleman K, Baujat G, Cole TR, Das S, Horn D, Hughes HE, Temple IK, Faravelli F, Waggoner D, Turkmen S, Cormier-Daire V, Irrthum A, Rahman N. Genotype-phenotype associations in Sotos syndrome: an analysis of 266 individuals with NSD1 aberrations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005b;77:193–204.

- Tatton-Brown K, Rahman N. Clinical features of NSD1-positive Sotos syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol. 2004;13:199–204.

- Lane C, Milne E, Freeth M. The cognitive profile of Sotos syndrome. J Neuropsychol. 2019;13:240–52.

- de Boer L, le Cessie S, Wit JM. Auxological data in patients clinically suspected of Sotos syndrome with NSD1 gene alterations. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:1142–4.

- Agwu JC, Shaw NJ, Kirk J, Chapman S, Ravine D, Cole TR. Growth in Sotos syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:339–42.

- Tatton-Brown K, Rahman N. Sotos syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:264–71.

- Villani A, Greer MC, Kalish JM, Nakagawara A, Nathanson KL, Pajtler KW, Pfister SM, Walsh MF, Wasserman JD, Zelley K, Kratz CP. Recommendations for cancer surveillance in individuals with RASopathies and other rare genetic conditions with increased cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:e83–e90.

- Schilling FH, Spix C, Berthold F, Erttmann R, Fehse N, Hero B, Klein G, Sander J, Schwarz K, Treuner J, Zorn U, Michaelis J. Neuroblastoma screening at one year of age. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1047–53.

- Scott RH, Walker L, Olsen ØE, Levitt G, Kenney I, Maher E, Owens CM, Pritchard-Jones K, Craft A, Rahman N. Surveillance for Wilms tumour in at-risk children: pragmatic recommendations for best practice. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:995–9.