What is Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome also called insulin resistance syndrome or “syndrome X”, by definition is not a disease but is a clustering of individual metabolic risk factors and medical conditions linked to overweight and obesity that puts people at risk for developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (coronary artery disease a condition in which a waxy substance called plaque builds up inside the coronary heart arteries), insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and vascular and neurological complications such as a cerebrovascular accident 1. Metabolic disarrangement becomes a metabolic syndrome if the patient has any three of the following 2:

- Waist circumference more than 40 inches in men and 35 inches in women (abdominal obesity). A large waistline, also called abdominal obesity or “having an apple shape.” Too much fat around the stomach is a greater risk factor for heart disease than too much fat in other parts of the body.

- Elevated triglycerides 150 milligrams per deciliter of blood (mg/dL) or greater (hypertriglyceridemia)

- Reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) less than 40 mg/dL in men or less than 50 mg/dL in women

- Elevated fasting glucose of 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or greater (hyperglycemia)

- Blood pressure values of systolic 130 mmHg or higher and/or diastolic 85 mmHg or higher (hypertension)

More recently the International Diabetes Federation, for a person to be defined as having the metabolic syndrome they must have 3:

- Central obesity (defined as waist circumference* with ethnicity specific values)

- * If BMI is >30kg/m², central obesity can be assumed and waist circumference does not need to be measured.

- Country/Ethnic specic values for waist circumference:

- Europids*: In the USA, the ATP III values (102 cm male; 88 cm female) are likely to continue to be used for clinical purposes. In other countries waist circumference for male ≥ 94 cm; female ≥ 80 cm

- South Asians: Based on a Chinese, Malay and Asian-Indian population, waist circumference for male ≥ 90 cm; female ≥ 80 cm

- Chinese: Waist circumference for male ≥ 90 cm; female ≥ 80 cm

- Japanese**: Waist circumference for male ≥ 90 cm; female ≥ 80 cm

- Ethnic South and Central Americans: Use South Asian recommendations until more specific data are available

- Sub-Saharan Africans: Use European data until more specific data are available

- Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East (Arab) populations: Use European data until more specific data are available

- Plus any two of the following four factors:

- Raised triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality

- Reduced HDL cholesterol in males < 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L); in females < 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality

- Raised blood pressure systolic BP ≥ 130 or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mm Hg or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension

- Raised fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes. If above 5.6 mmol/L or 100 mg/dL, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is strongly recommended but is not necessary to define presence of metabolic syndrome.

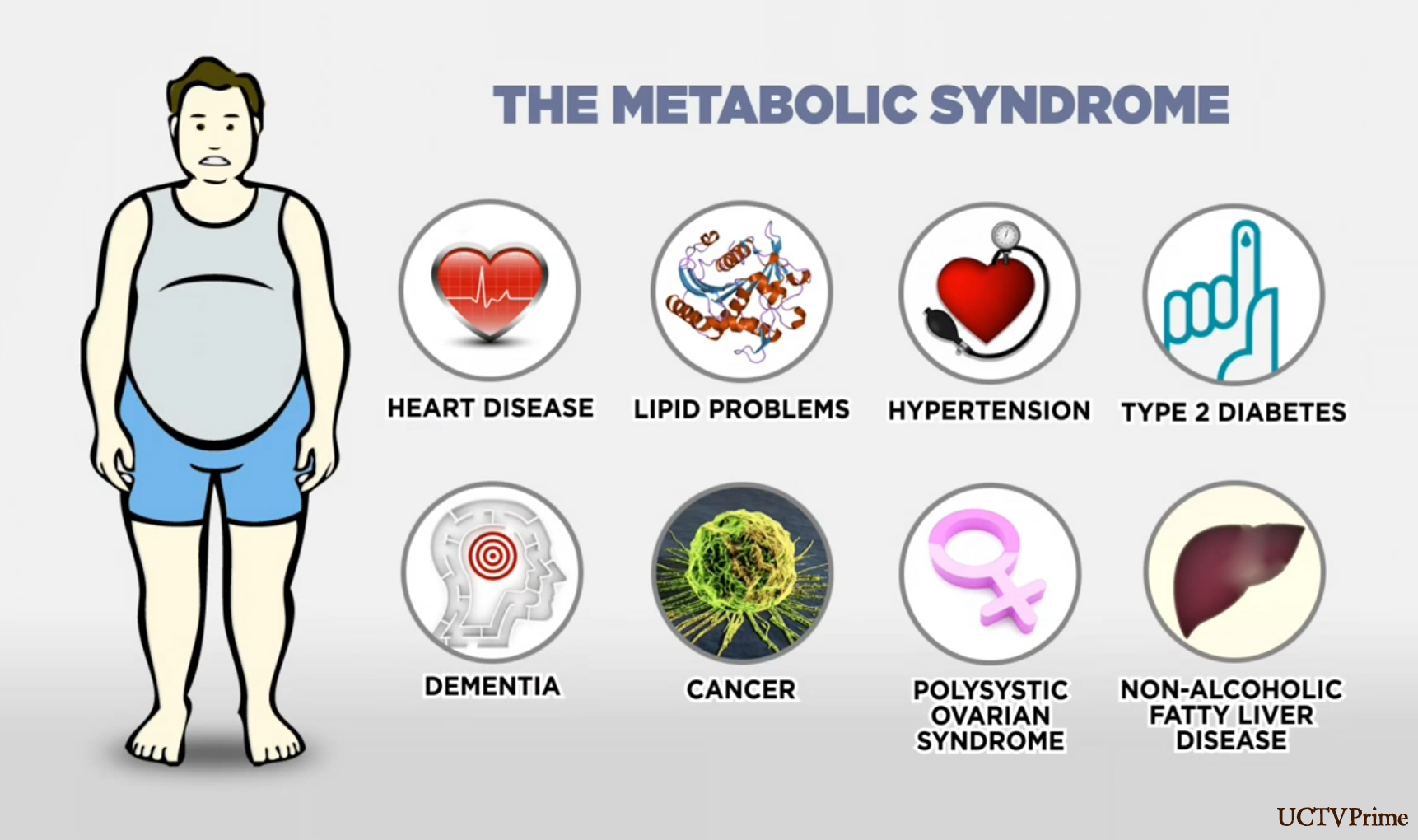

Metabolic syndrome has serious implications on an individual’s health and healthcare costs. The high prevalence of the metabolic syndrome has considerable clinical implications, because the syndrome is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease 4. People who have metabolic syndrome often also have excessive blood clotting and inflammation throughout the body. Metabolic syndrome is also associated with other comorbidities including the proinflammatory state, prothrombotic state, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), cholesterol gallstone disease, and reproductive disorders 1. Researchers don’t know whether these conditions cause metabolic syndrome or worsen it 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

Data from several studies have demonstrated that the metabolic syndrome is associated with a 3 to 4 fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular mortality, and stroke 11, 12. Most studies have found that the metabolic syndrome is associated with an approximate doubling of cardiovascular disease risk and a 5-fold increased risk for type 2 diabetes 1. Metabolic Syndrome involves a cluster of symptoms that, when present together, increase the chances of acquiring a chronic disease, such as diabetes, heart disease and liver disease 13. About 34% of U.S. adults and 20 to 30 percent of the adult population in most countries have metabolic syndrome 14. Although these risks are significant, there is good news. Metabolic syndrome can be treated and you can reduce your risks for cardiovascular events by maintaining a healthy weight, eating a heart-healthy diet, getting adequate physical activity, and following your healthcare providers’ instructions. In people for whom lifestyle change is not enough and who are considered to be at high risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), drug therapy may be required to treat the metabolic syndrome.

Other Names for Metabolic Syndrome

- Syndrome X

- Dysmetabolic syndrome

- Hypertriglyceridemic waist

- Insulin resistance syndrome

- Obesity syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is becoming more common due to a rise in obesity rates among adults. In the future, metabolic syndrome may overtake smoking as the leading risk factor for heart disease.

Metabolic syndrome has become increasingly common in the United States. Several factors increase the likelihood of acquiring metabolic syndrome:

- Obesity/overweight

- Obesity is an important potential cause of metabolic syndrome. Excessive fat in and around the abdomen is most strongly associated with metabolic syndrome. However, the reasons abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome seem to be linked are complex and not fully understood.

- Insulin resistance: Metabolic syndrome is closely associated with a generalized metabolic disorder called insulin resistance, in which the body can’t use insulin efficiently. Some people are genetically predisposed to insulin resistance.

- Race and gender: When people have the same body mass index (BMI), Mexican Americans have the highest rate of metabolic syndrome, followed by Caucasians and African Americans. Men are more likely than women to develop metabolic syndrome.

According to the American Heart Association, 56 million Americans have metabolic syndrome, or roughly one in five people (22.9%) over age 20, placing them at higher risk for chronic disease 15. Metabolic syndrome runs in families and varies across racial-ethnic groups. The most recent data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) shows the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is on a decline with 24% in men 16 and 22% in women 17. It is necessary to recognize the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in America as through intervention the progression of the syndrome can be halted and potentially reversed 18. However, the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome is increasing not only in Europe, but also in Asian countries such as China, India, and South Korea 1.

In addition to type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome has been linked to the following health disorders:

- Obesity

- Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

- Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Chronic kidney disease

However, not everyone with these disorders has insulin resistance and some people may have insulin resistance without getting these disorders.

People who are obese or who have metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes or prediabetes often also have low-level inflammation throughout the body and blood clotting defects that increase the risk of developing blood clots in the arteries. These conditions contribute to increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

Although it is unclear whether there is a unifying pathogenic mechanism that could decipher the pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome, it is highly likely that abdominal obesity and insulin resistance could play a central role in promoting the development of the metabolic syndrome 19. Therefore, lifestyle modification and weight loss should be considered to be the first step for preventing or treating the metabolic syndrome 20. In addition, other cardiac risk factors should be actively managed in individuals with the metabolic syndrome 21.

Metabolic Syndrome Criteria

Metabolic Syndrome is composed of the following Five Symptoms. You must have at least three of the five metabolic risk factors to be diagnosed with metabolic syndrome.

- Large Waist Size: 35 inch (>88 cm) or more for women and 40 inch (>102 cm) for men

- High triglycerides: 150 mg/dL or higher (or use of cholesterol medication)

- High total cholesterol or HDL levels under 50 mg/dL for women, 40 mg for men

- High blood pressure: 135/85 mmHg or higher

- High blood sugar: fasting blood glucose level of 100 mg/dL or above, or taking medication for elevated blood glucose

Criteria for clinical diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome in childhood and adolescence

Obviously, the diagnostic standards for adults cannot be simply used in children and adolescents, particularly in toddlers and even younger children, because of significant changes in body size and continuous growth and development with age 1. Furthermore, puberty has a drastic effect on fat redistribution in the body, leading to an enhanced insulin sensitivity in the liver, adipose tissues, and muscle, as well as an increased insulin secretion by the pancreatic β cells. In other words, compared to that in adults, insulin sensitivity is lower by 25 to 50% during childhood and returns to normal after pubertal development. Growth and developmental changes with age are also associated with physiological adjustments in blood pressure, plasma lipid levels, and energy metabolism, as well as glucose and lipid metabolism in the liver and adipose tissues. All these factors make it difficult to develop a precise definition for the diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome in young people with different ages, different ethnic/racial groups, and genders. In particular, because of the lack of reference values for some of the components of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents, a consensus definition is not proposed easily.

For children and adolescents, the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on the Epidemiology and Prevention of Diabetes set a practical clinical criterion for the diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome in 2007 22. The definition of the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescence is central obesity plus the presence of two or more than two components 22. Based on a modification of previous adult standards, the International Diabetes Federation has promoted a new criterion for the diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome mainly for children and adolescents between the ages of 10 and 16 years, as shown in Table 1 23. The definition of the metabolic syndrome in this age group is central obesity (≥90th percentile) plus the presence of two or more other components, including hypertriglyceridemia (≥1.7 mmoL/L; ≥150 mg/dL), high blood glucose (≥5.6 mmoL/L; ≥100 mg/dL), high blood pressure (≥130 mmHg systolic or ≥85 mmHg diastolic), or low HDL-cholesterol levels (≤1.03 mmoL/L; ≤40 mg/dL). To date, the available data, however, were not sufficient to make a recommendation for children aged <6 years. For children aged between 6 and 10 years, as the metabolic syndrome cannot be diagnosed, they should be strongly recommended weight loss, especially those with abdominal obesity. For adolescents aged 16 years or older, the adult criteria could be used.

In 2014, a new criterion for defining the metabolic syndrome in prepubertal children was proposed by the identification and prevention of dietary- and lifestyle-induced health effects in children and infants (IDEFICS) study 24, which addressed the limitations of previous definitions in children and the need for early diagnosis in young people. Using reference values from the study of 18,745 children in eight European countries, the IDEFICS study set up the age-specific and sex-specific (and height-specific in the case of blood pressure) percentiles to identify cutoffs for the components of the metabolic syndrome in children at the age of 2-11 years 24. However, the proposed cutoffs were based on a statistical definition and these did not allow to quantify the risk of subsequent diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Table 1. The International Diabetes Federation definition of the at-risk group and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents (2007)

| Age group (yr) | Obesity (waist circumference) | Triglycerides | HDL-C | Blood pressure | Plasma glucose |

| 6–<10* | ≥90th percentile | ||||

| 10–<16 | ≥90th percentile or adult cut-off if lower | ≥1.7 mmoL/L (≥150 mg/dL) | <1.03 mmoL/L (<40 mg/dL) | Systolic BP ≥130 or Diastolic BP ≥85 mmHg | fasting plasma glucose ≥5.6 mmoL/L (100 mg/dL)‡ or known type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| 16+ (adult criteria) | waist circumference ≥94 cm for Caucasian males and ≥80 cm for Caucasian females, with ethnic-specific values for other groups†) | ≥1.7 mmoL/L (≥150 mg/dL) or specific treatment for high triglycerides | <1.03 mmoL/L (<40 mg/dL) in males and <1.29 mmoL/L (<50 mg/dL) in females, or specific treatment for low HDL | Systolic BP ≥130 or diastolic BP ≥85 mmHg or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension | fasting plasma glucose ≥5.6 mmoL/L (100 mg/dL)‡ or known type 2 diabetes mellitus |

Footnotes: *The metabolic syndrome cannot be diagnosed, but further measurements should be made if there is a family history of the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and/or obesity.

†For those of South and South-East Asian, Japanese, and ethnic South and Central American origin, the cutoffs should be ≥90 cm for men, and ≥80 cm for women. The IDF Consensus Group recognize that there are ethnic, gender and age differences, but research is still needed on outcomes to establish risk.

‡For clinical purposes, but not for diagnosing the metabolic syndrome, if fasting plasma glucose is 5.6–6.9 mmoL/L (100–125 mg/dL) and it is not known to have diabetes, an oral glucose tolerance test should be performed.

Diagnosing the metabolic syndrome requires the presence of central obesity plus any two of the other four factors.

Abbreviations: BP = blood pressure; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

[Source 22 ]

How Is Metabolic Syndrome Diagnosed?

Because metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions, many of which must be determined with lab work, metabolic syndrome is not one that an individual can assess without the help of a healthcare provider. However, if you have a large waist circumference and have been told by your healthcare provider that you have another condition like elevated triglycerides, high blood sugar or high blood pressure, you will need to discuss your combined risks with your healthcare provider.

Your doctor will diagnose metabolic syndrome based on the results of a physical exam and blood tests. You must have at least three of the five metabolic risk factors to be diagnosed with metabolic syndrome.

The blood work should include hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) to screen for insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus type 2. A lipid panel should also be drawn to assess for abnormally elevated triglyceride level, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level, and elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level. The initial evaluation should also include a basic metabolic panel to evaluate for renal dysfunction and examine glucose level. Further studies such as C-reactive protein (CRP), liver panel, thyroid study, and uric acid can be drawn to investigate the existence of further and support the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome. Imaging studies can be ordered when appropriate. For instance, anyone suspected to have atherosclerotic coronary artery disease should have an electrocardiogram to evaluate for signs of cardiac ischemia, infarct, arrhythmias, as well as evaluate for hypertension with structural heart disease. If warranted, patients should be evaluated further with cardiac stress testing including electrocardiogram stress test, stress echocardiography, stress single-photon emission computed tomography or myocardial perfusion imaging 25.

Metabolic Risk Factors

1) A Large Waistline

Having a large waistline means that you carry excess weight around your waist (abdominal obesity). This is also called having an “apple-shaped” figure. Your doctor will measure your waist to find out whether you have a large waistline.

A waist measurement of 35 inches or more for women (>88 cm) or 40 inches or more for men (>102 cm) is a metabolic risk factor. A large waistline means you’re at increased risk for heart disease and other health problems.

2) A High Triglyceride Level

Triglycerides are a type of fat found in the blood. A triglyceride level of 150 mg/dL or higher (or being on medicine to treat high triglycerides) is a metabolic risk factor. (The mg/dL is milligrams per deciliter—the units used to measure triglycerides, cholesterol, and blood sugar.)

3) A Low HDL Cholesterol Level

HDL cholesterol sometimes is called “good” cholesterol. This is because it helps remove cholesterol from your arteries.

An HDL cholesterol level of less than 50 mg/dL for women and less than 40 mg/dL for men (or being on medicine to treat low HDL cholesterol) is a metabolic risk factor.

4) High Blood Pressure

A blood pressure of 130/85 mmHg or higher (or being on medicine to treat high blood pressure) is a metabolic risk factor. (The mmHg is millimeters of mercury—the units used to measure blood pressure.)

If only one of your two blood pressure numbers is high, you’re still at risk for metabolic syndrome.

5) High Fasting Blood Sugar

A normal fasting blood sugar level is less than 100 mg/dL. A fasting blood sugar level between 100–125 mg/dL is considered prediabetes. A fasting blood sugar level of 126 mg/dL or higher is considered diabetes.

A fasting blood sugar level of 100 mg/dL or higher (or being on medicine to treat high blood sugar) is a metabolic risk factor.

About 85 percent of people who have type 2 diabetes—the most common type of diabetes—also have metabolic syndrome. These people have a much higher risk for heart disease than the 15 percent of people who have type 2 diabetes without metabolic syndrome.

Metabolic Syndrome Causes

Metabolic syndrome has several causes that act together:

- Overweight and obesity

- An inactive lifestyle

- Insulin resistance, a condition in which the body can’t use insulin properly. Insulin is a hormone that helps move blood sugar into your cells to give them energy. Insulin resistance can lead to high blood sugar levels.

- Age – your risk goes up as get older

- Genetics – ethnicity and family history

Some people are genetically prone to develop insulin resistance or metabolic syndrome. Other people develop metabolic syndrome by 26, 27:

- Putting on excess body fat

- Failing to get enough physical activity

The crux of metabolic syndrome is a buildup of fatty tissue and tissue dysfunction that in turn leads to insulin resistance 28. Proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), leptin, adiponectin, plasminogen activator inhibitor, and resistin, are released from the enlarged adipose tissue, which alters and impacts insulin handling adversely 28. Insulin resistance can be acquired or may be due to genetic disposition. Impairment of the signaling pathway, insulin receptor defects, and defective insulin secretion can all contribute towards insulin resistance. Over time, the culmination of this cause development of metabolic syndrome that presents as vascular and autonomic damage 29.

The distribution of body fat is also important and it is known that upper body fat plays a strong role in developing insulin resistance. Fat accumulation can be intraperitoneal (visceral fat) or subcutaneous. Visceral fat may contribute to insulin resistance more strongly than subcutaneous fat. However, both are known to play a role in the development of the metabolic syndrome. In upper body obesity, high levels of nonesterified fatty acids are released from the adipose tissue causing lipid to accumulate in other parts of the body such as liver and muscle, further perpetuating insulin resistance.

You can control some of the causes, such as overweight and obesity, an inactive lifestyle, and insulin resistance.

You can’t control other factors that may play a role in causing metabolic syndrome, such as growing older. Your risk for metabolic syndrome increases with age.

You also can’t control genetics (ethnicity and family history), which may play a role in causing the condition. For example, genetics can increase your risk for insulin resistance, which can lead to metabolic syndrome.

Researchers continue to study conditions that may play a role in metabolic syndrome, such as:

- A fatty liver (excess triglycerides and other fats in the liver)

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome (a tendency to develop cysts on the ovaries)

- Gallstones

- Breathing problems during sleep (such as sleep apnea)

Fortunately, many of the factors that contribute to metabolic syndrome can be addressed through lifestyle changes, such as diet, exercise, and weight loss. By making these changes, you can significantly reduce your risks.

Metabolic Syndrome Risk Factors

The five conditions described below are metabolic risk factors. You can have any one of these risk factors by itself, but they tend to occur together. You must have at least three metabolic risk factors to be diagnosed with metabolic syndrome 30.

- A large waistline. This also is called abdominal obesity or “having an apple shape.” Excess fat in the stomach area is a greater risk factor for heart disease than excess fat in other parts of the body, such as on the hips.

- A high triglyceride level (or you’re on medicine to treat high triglycerides). Triglycerides are a type of fat found in the blood.

- A low HDL cholesterol level (or you’re on medicine to treat low HDL cholesterol). HDL sometimes is called “good” cholesterol. This is because it helps remove cholesterol from your arteries. A low HDL cholesterol level raises your risk for heart disease.

- High blood pressure (or you’re on medicine to treat high blood pressure). Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of your arteries as your heart pumps blood. If this pressure rises and stays high over time, it can damage your heart and lead to plaque buildup.

- High fasting blood sugar (or you’re on medicine to treat high blood sugar). Mildly high blood sugar may be an early sign of diabetes.

People at greatest risk for metabolic syndrome have these underlying causes:

- Abdominal obesity (a large waistline)

- An inactive lifestyle

- Insulin resistance

Some people are at risk for metabolic syndrome because they take medicines that cause weight gain or changes in blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. These medicines most often are used to treat inflammation, allergies, HIV, and depression and other types of mental illness.

Populations Affected

Some racial and ethnic groups in the United States are at higher risk for metabolic syndrome than others. Mexican Americans have the highest rate of metabolic syndrome, followed by whites and blacks.

Other groups at increased risk for metabolic syndrome include:

- People who have a personal history of diabetes

- People who have a sibling or parent who has diabetes

- Women when compared with men

- Women who have a personal history of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which is a tendency to develop cysts on the ovaries.

Heart Disease Risk

Metabolic syndrome increases your risk for coronary heart disease. Other risk factors, besides metabolic syndrome, also increase your risk for heart disease. For example, a high LDL (“bad”) cholesterol level and smoking are major risk factors for heart disease. For details about all of the risk factors for heart disease, go to the Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors Health Topic.

Even if you don’t have metabolic syndrome, you should find out your short-term risk for heart disease. The National Cholesterol Education Program divides short-term heart disease risk into four categories. Your risk category depends on which risk factors you have and how many you have.

Your risk factors are used to calculate your 10-year risk of developing heart disease. The National Cholesterol Education Program has an online calculator 31 that you can use to estimate your 10-year risk of having a heart attack.

- High risk: You’re in this category if you already have heart disease or diabetes, or if your 10-year risk score is more than 20 percent.

- Moderately high risk: You’re in this category if you have two or more risk factors and your 10-year risk score is 10 percent to 20 percent.

- Moderate risk: You’re in this category if you have two or more risk factors and your 10-year risk score is less than 10 percent.

- Lower risk: You’re in this category if you have zero or one risk factor.

Even if your 10-year risk score isn’t high, metabolic syndrome will increase your risk for coronary heart disease over time.

Metabolic Syndrome Overview

Your risk for heart disease, diabetes, and stroke increases with the number of metabolic risk factors you have. The risk of having metabolic syndrome is closely linked to overweight and obesity and a lack of physical activity.

Insulin resistance also may increase your risk for metabolic syndrome. Insulin resistance is a condition in which the body can’t use its insulin properly. Insulin is a hormone that helps move blood sugar into cells where it’s used for energy. Insulin resistance can lead to high blood sugar levels, and it’s closely linked to overweight and obesity. Genetics (ethnicity and family history) and older age are other factors that may play a role in causing metabolic syndrome.

Metabolic Syndrome is linked to heart disease and diabetes

Sixteen million Americans have heart disease, which is the #1 killer in the United States. Growing scientific evidence is helping identify the various ways that sugar is implicated. We know that metabolic syndrome is a strong predictor of heart disease. Consuming too many added sugars also can lead to excess weight gain, which strains the heart.

Diabetes, which affects 25.8 million Americans, is of equal concern to public health. Diabetes can cause kidney failure, lower-limb amputations, and blindness, and doubles the risk of colon and pancreatic cancers. Diabetes is strongly associated with coronary artery disease and Alzheimer’s disease. It’s also a discriminatory disease: compared to white adults, the risk of being diagnosed with diabetes is 18% higher among Asian Americans, 66% higher among Hispanics and 77% higher among African-Americans.

Metabolic syndrome pathophysiology

Although the exact cause of the metabolic syndrome is not fully understood, insulin resistance is considered as a key factor for the development of the metabolic syndrome and is largely involved in the pathogenesis of individual metabolic components of the syndrome 32. As found by the insulin-modified, frequently-sampled intravenous glucose tolerance assay, insulin sensitivity is significantly lower in patients with two or more than two components of the metabolic syndrome compared to those with none of these components 33. It is well known that insulin plays a critical role in the regulation of glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in many organs and tissues such as the liver, adipose tissue, muscle, heart, and gastrointestinal track 34. Metabolic syndrome adversely influences several body systems. Insulin resistance causes microvascular damage, which predisposes a patient to endothelial dysfunction, vascular resistance, hypertension, and vessel wall inflammation. Endothelial damage can impact the homeostasis of the body causing atherosclerotic disease and the development of hypertension. Furthermore, hypertension adversely affects several body functions including increased vascular resistance and stiffness causing peripheral vascular disease, structural heart disease comprising of left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiomyopathy, and leading to renal impairment.

Accumulated effects of endothelial dysfunction and hypertension due to metabolic syndrome can further result in ischemic heart disease. Endothelial dysfunction due to increased levels of plasminogen activator type 1 and adipokine levels can cause thrombogenicity of the blood and hypertension causes vascular resistance through which coronary artery disease can develop. Also, dyslipidemia associated with metabolic syndrome can drive the atherosclerotic process leading to symptomatic ischemic heart disease 35.

Metabolic Syndrome Prevention

Because obesity is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, this may continue into childhood and adolescence until adulthood. Therefore, the best way to prevent metabolic syndrome is to adopt heart-healthy lifestyle changes with a special focus on keeping weight within normal range 36. Lifestyle changes includes eating healthy diet and appropriate amounts of total calories, increasing physical activity, and maintaining the right weight. Make sure to schedule routine doctor visits to keep track of your cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood sugar levels. Speak with your doctor about a blood test called a lipoprotein panel, which shows your levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides.

In general, the therapeutic interventions are divided into (i) lifestyle modification, (ii) pharmaceutical therapy, and (iii) bariatric surgery 37.

Healthy diet

It is well known that Western diet contains high total calories, cholesterol, saturated fatty acids, refined carbohydrates, proteins, and salt, as well as low fibers, and it is highly associated with the metabolic abnormalities 38. Moreover, overconsumption of fast foods in combination with inactive physical activity is strongly associated with the high prevalence of overweight, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents over the past 30 years 39. Clearly, eating healthy diet has a significant impact on all the components of the metabolic syndrome 40. Although each case should be treated individually, it is important to recommend a healthy diet with low total calories, cholesterol, saturated fat, and sodium, as well as high unsaturated fat, complex carbohydrates, and fiber 41. This should be the first step in halting the development of metabolic abnormalities in children and adolescents 42.

It is well established that weight loss has a great benefit for the treatment of all the components of the metabolic syndrome, including excessive adiposity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia 43. The intensive lifestyle intervention with a special focus on a significant decrease in daily caloric intake could lead to weight loss 44. It is worthwhile noting that even if the magnitude of weight loss is not drastic, some metabolic abnormalities could be improved. As shown by the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study 45, lifestyle intervention with modest weight loss could significantly reduce the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome compared with the control group. A modest weight loss often improves blood pressure regulation and decreases the risk of developing hypertension 46. In addition, weight loss may increase plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations, as well as reduce plasma triglyceride and fasting blood glucose levels, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values 47. A 7-day negative energy balance without measurable weight loss has found that reducing daily caloric intake may improve insulin sensitivity 48.

Low sodium intake has a good benefit for blood pressure regulation because clinical and epidemiological studies have revealed a clear positive relationship between sodium intake and blood pressure 49. It is well known that excessive sodium intake can cause hypertension not only in adults, but also in children and adolescents 40. As shown by the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Study 50, lower sodium intake reduces blood pressure in people with mild or moderate hypertension, as well as sodium restriction may be associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular disease and congestive heart failure. Therefore, it is strongly recommended that sodium restriction or low sodium diet should be given to children and adolescents, especially to obese young people. This is a key step for the prevention and the treatment of hypertension, a major component of the metabolic syndrome 51.

Here are the approximate amounts of sodium in a given amount of salt:

- 1/4 teaspoon salt = 575 mg sodium

- 1/2 teaspoon salt = 1,150 mg sodium

- 3/4 teaspoon salt = 1,725 mg sodium

- 1 teaspoon salt = 2,300 mg sodium

The body needs only a small amount of sodium (less than 500 milligrams per day) to function properly. That’s a mere smidgen — the amount in less than ¼ teaspoon. Very few people come close to eating less than that amount. Plus, healthy kidneys are great at retaining the sodium that your body needs.

It has been recognized that high dietary cholesterol is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and cholesterol gallstone disease, with all of these being the major components of the metabolic syndrome 52. Therefore, it is important to recommend a low cholesterol diet. The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines and the recommendations from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have proposed a lower (<100 mg/dL) target for plasma LDL-cholesterol levels for individuals at high risk for adverse cardiovascular events 53. Therefore, the low cholesterol diet could reduce not only total cholesterol concentrations in the plasma, liver, and bile, but also plasma LDL-cholesterol concentrations 54.

Dietary carbohydrates are often divided into two types: simple and complex carbohydrate. Complex carbohydrates (starches) are made up of sugar molecules that are strung together in long, complex chains. Complex carbohydrates are found in foods such as peas, beans, whole grains, and vegetables. It is recommended that complex carbohydrates should make up most of daily carb intake 55. In contrast, simple carbohydrates, especially refined carbohydrates such as added sugars, should be limited 56. Simple carbohydrates are broken down quickly by the body to be used as energy. Simple carbohydrates are found naturally in foods such as fruits, milk, and milk products. Simple carbohydrates are also found in processed and refined sugars such as candies, table sugar, syrups, soft drinks, fruit drinks, cakes, cookies, dairy desserts and pies 57. Although chemical structures are identical between added sugars and naturally occurring simple sugars, e.g., sugars found in fruit, added sugars contain less or no vitamins and minerals. Thus, large amounts of added sugar intake could lead to a lack of nutrients found in foods. In addition, added sugars quickly raise blood glucose levels and increase the risk of insulin resistance. Based on these observations, a concept was proposed that carbohydrates are classified as “good” or “bad” for disease risk, as indicated by the glycemic index (GI index) 58. For example, low glycemic index foods may improve components, i.e., hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia, of the metabolic syndrome, whereas high glycemic index foods may increase the risk of insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome 58. Moreover, the Nurses’ Health Study showed that a lower glycemic load is associated with a decreased risk of developing cardiovascular disease 59.

For most people, a carbohydrate intake of 45 to 65% of total daily calories is appropriate, as recommended by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). In general, a diet high in complex, unrefined carbohydrates with an emphasis on fiber (25 g per day) and low in added sugars (<25% of caloric intake) is recommended for individuals with or at risk for the metabolic syndrome 60, 61. Clinical studies found that high daily carbohydrate intake is associated with increased plasma total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and triglyceride concentrations, and reduced HDL-cholesterol levels 62. In contrast, low carbohydrate diets may improve glucose metabolism in subjects with insulin resistance and/or type 2 diabetes 63. It is unclear whether low daily carbohydrate intake may influence lipid metabolism and reduce the risk of hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia. Another explanation is that low daily carbohydrate intake may enhance insulin sensitivity, thus improving cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism in the liver and plasma 64, 65. Although lower carbohydrate diets may be helpful in weight loss in the short term, the effects on long-term weight loss have been mixed and further studies are needed.

Most studies suggested that high fat intake, i.e., 20 to 40% of caloric intake, may increase the risk of overweight and obesity, thereby leading to insulin resistance. In addition, high fat intake may increase the prevalence of NAFLD, NASH, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease 66. However, because some conflicting results have been reported, it is unclear whether increased fat intake per se may have an impact on insulin sensitivity or may impair glucose metabolism 67. Although the average fat intake in the USA has been reduced from 36.9 to 32.8% in men and from 36.1 to 32.8% in women over the past 50 years, there has been a marked increase in overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome during the same time period 68. This suggested that it may be the type of fats consumed, rather than the total amount of intake, producing a greater effect on the components of the metabolic syndrome 69.

The fatty acids in fat are often divided into two types: saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, with the latter being subclassified to monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids 70. In general, saturated, but not unsaturated, fatty acids are associated with impaired glucose tolerance and obesity, as well as increased risk of developing NAFLD, NASH, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease 71. It is highly likely that a diet with high unsaturated fatty acids and low saturated fatty acids may improve insulin sensitivity and plasma lipid and lipoprotein metabolism 72. The Nurses’ Health Study has found that a 5% increase in saturated fat intake is associated with a 17% increment in risk of coronary heart disease 73. In contrast, increased monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat intake may be associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease 74.

Because of a lack of sufficient clinical and epidemiological data, it is unclear whether protein intake has an association with the development of the metabolic syndrome 75. A daily protein intake of 10 to 35% of total calories has been recommended for the general population 76. Nevertheless, appropriate daily protein intake is good for people, regardless of whether they have normal weight or are obese, except for patients with nephropathy 77.

Physical activity

Epidemiological surveys have found that a sedentary lifestyle in combination with unhealthy eating habits likely increases the risk of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) 78. Thus, increasing exercise to reduce and/or maintain weight is another important approach for preventing or treating the metabolic syndrome 79. Many epidemiological reports have shown that low physical activity is associated with increased prevalence of the metabolic syndrome, whereas high physical activity is likely to protect against the development of the metabolic syndrome 80. Indeed, higher cardiorespiratory fitness and extensive physical activity have been shown to improve glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity and reduce cardiovascular disease mortality, as well as the risk of type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [342,343,344,345]. It is likely that increasing physical activity could reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, and NASH through weight loss 81. Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness and intensive physical activity prevent the development of the metabolic syndrome likely through their effects on each of the individual components 82. Clinical studies have revealed that combining with healthy dietary intake, high-intensity exercise, i.e., aerobic exercise, is very effective at enhancing insulin sensitivity and reducing weight, particularly abdominal adiposity, as well as potentially improving hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia 83.

As shown by a systematic review of the literature, aerobic exercise may reduce visceral adiposity in a dose-dependent manner 84. However, it is unclear whether exercise could reduce visceral adipose tissue in the absence of weight loss 85. To achieve continued benefit of exercise on insulin action, the American Heart Association and the American College of Sports Medicine have recommended exercise at least 30 minutes/day most days of the week 86. Aerobic exercise may produce a persistent effect on glucose tolerance and insulin action beyond the immediate post-exercise effects and possibly through weight loss 87. More importantly, while maintaining weight, regular aerobic exercise is still critical to reducing abdominal fat tissue and preventing weight regain in individuals who have successfully lost weight 88.

Pharmaceutical therapy

The currently available therapeutic strategies focus mainly on treating the individual components of the metabolic syndrome, with the overall goals of reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes or preventing them. Moreover, some therapeutic options may have a marked impact on two or more than two components of the metabolic syndrome 89. Nevertheless, many therapeutic efforts on the treatment of the visceral obesity and insulin resistance associated with the metabolic syndrome may provide the most overall success in achieving these goals 90.

Metabolic Syndrome Symptoms and Signs

Metabolic syndrome is a group of risk factors that raises your risk for heart disease and other health problems, such as diabetes and stroke. These risk factors can increase your risk for health problems even if they’re only moderately raised (borderline-high risk factors).

- Most of the metabolic risk factors have no signs or symptoms, although a large waistline is a visible sign.

- Some people may have symptoms of high blood sugar if diabetes—especially type 2 diabetes—is present.

- Symptoms of high blood sugar often include increased thirst; increased urination, especially at night; fatigue (tiredness); and blurred vision.

- High blood pressure usually has no signs or symptoms. However, some people in the early stages of high blood pressure may have dull headaches, dizzy spells, or more nosebleeds than usual.

Metabolic Syndrome Treatment

It is possible to prevent or delay metabolic syndrome, mainly with lifestyle changes. Treating metabolic syndrome requires addressing several conditions together. A healthy lifestyle is a lifelong commitment. Improving your overall cardiovascular health will greatly improve the individual conditions that make up metabolic syndrome. Successfully controlling metabolic syndrome requires long-term effort and teamwork with your health care providers.

Heart-healthy lifestyle changes are the first line of treatment for metabolic syndrome. If heart-healthy lifestyle changes aren’t enough, your doctor may prescribe medicines. Medicines are used to treat and control risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high triglycerides, low HDL (“good”) cholesterol, and high blood sugar.

Goals of Treatment

- The major goal of treating metabolic syndrome is to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease. Treatment is directed first at lowering LDL cholesterol and high blood pressure and managing diabetes (if these conditions are present).

- The second goal of treatment is to prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes, if it hasn’t already developed. Long-term complications of diabetes often include heart and kidney disease, vision loss, and foot or leg amputation. If diabetes is present, the goal of treatment is to reduce your risk for heart disease by controlling all of your risk factors.

Heart-Healthy Lifestyle Changes

Heart-healthy lifestyle changes include heart-healthy eating, aiming for a healthy weight, managing stress, physical activity, and quitting smoking.

Here’s what you can do starting today 91 :

- Eat better. Heart-healthy eating includes a diet rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, lean meats and fish, and low-fat or fat-free dairy products and avoid processed food, which often contains partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, and is high in salt and added sugar.

- Get active. Incorporate at least 150 minutes of moderately vigorous physical activity into your weekly routine. Walking is the easiest place to start, but you may want to experiment to find something else you like to do that gets your heart rate up. If needed, break your exercise up into several short, 10-minute sessions throughout the day to reach your goal.

- Lose weight. Aiming for a healthy weight. Reduce your risk for heart disease by successfully losing weight and keeping it off. Learn your recommended calorie intake, the amount of food calories you’re consuming, and the energy calories you’re burning off with different levels of physical activity. Balance healthy eating with a healthy level of exercise to reach your goals.

- Managing stress.

- Quitting smoking. The chemicals in tobacco smoke harm your blood cells. They also can damage the function of your heart and the structure and function of your blood vessels. Smoking is a major risk factor for heart disease. When combined with other risk factors—such as unhealthy blood cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, and overweight or obesity—smoking further raises the risk of heart disease.

Lifestyle changes can help you control your risk factors and reduce your risk for coronary heart disease and diabetes.

If you already have heart disease or diabetes, lifestyle changes can help you prevent or delay related problems. Examples of these problems include heart attack, stroke, and diabetes-related complications (for example, damage to your eyes, nerves, kidneys, feet, and legs).

If lifestyle changes aren’t enough, your doctor may recommend medicines. Take all of your medicines as prescribed by your doctor. Make realistic short- and long-term goals for yourself when you begin to make healthy lifestyle changes. Work closely with your doctor, and seek regular medical care.

When changes in lifestyle alone do not control the conditions related to metabolic syndrome, your health practitioner may prescribe medications to control blood pressure, cholesterol, and other symptoms. Carefully following your practitioner’s instructions can help prevent many of the long term effects of metabolic syndrome. Every step counts and your hard work and attention to these areas will make a difference in your health!

Foods that are good for your heart and arteries

A healthy diet can help protect your heart, improve your blood pressure and cholesterol, and reduce your risk of type 2 diabetes. A heart-healthy eating plan includes:

- Vegetables and fruits

- Beans or other legumes

- Lean meats and fish

- Low-fat or fat-free dairy foods

- Whole grains

- Healthy fats, such as olive oil

The following foods are the foundation of a heart-healthy eating plan:

- Vegetables such as leafy greens (spinach, collard greens, kale, cabbage), broccoli, and carrots

- Fruits such as apples, bananas, oranges, pears, grapes, and prunes

- Whole grains such as plain oatmeal, brown rice, and whole-grain bread or tortillas

- Fat-free or low-fat dairy foods such as milk, cheese, or yogurt

- Protein-rich foods:

- Fish high in omega-3 fatty acids (salmon, tuna, and trout)

- Lean meats such as 95% lean ground beef or pork tenderloin or skinless chicken or turkey

- Eggs

- Nuts, seeds, and soy products (tofu)

- Legumes such as kidney beans, lentils, chickpeas, black-eyed peas, and lima beans

- Oils and foods high in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats:

- Canola, corn, olive, safflower, sesame, sunflower, and soybean oils (not coconut or palm oil)

- Nuts such as walnuts, almonds, and pine nuts

- Nut and seed butters

- Salmon and trout

- Seeds (sesame, sunflower, pumpkin, or flax)

- Avocados

- Tofu

Research shows that the best foods that protect your heart and blood vessels, include the following:

- Fruits and Vegetables. Current World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for fruit intake combined with vegetable intake are a minimum 400 g/day 92. A recent meta-analysis indicated that the intake of 800 g/day of fruit was associated with a 27% reductions in relative risk of cardiovascular disease 93.

- Fatty fish (Omega-3 fatty acids). Omega-3 fatty acid is a polyunsaturated fatty acid that must be obtained through dietary intake from fish as well as other types of seafood as it is not produced naturally in the human body 94. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are essential fatty acids present in omega-3 95. Fatty fish such as salmon, sardines and mackerel are abundant sources of omega-3 fatty acids, healthy unsaturated fats that have been linked to lower blood levels of beta-amyloid—the protein that forms damaging clumps in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Omega-3 fatty acids are thought to help keep your blood vessels healthy and to help to reduce blood pressure. Research into this style of eating has shown a reduced risk of developing problems such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and raised cholesterol, which are all risk factors for heart disease 96. The American Heart Association recommends eating 2 servings of fish (particularly fatty fish) per week. A serving is 3.5 ounce cooked, or about ¾ cup of flaked fish. Fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, herring, lake trout, sardines and albacore tuna are high in omega-3 fatty acids 97. Eating oily fish is a nutritious choice which can form part of the Mediterranean diet (more bread, fruit, vegetables, fish and less meat, and replacing butter with unsaturated fat spreads). Researchers have also found that people who closely follow a traditional Mediterranean style diet are more likely to live a longer life and also are less likely to become obese. Try to eat fish at least twice a week, but choose varieties that are low in mercury, such as salmon, cod, canned light tuna, and pollack. If you’re not a fan of fish, ask your doctor about taking an omega-3 supplement, or choose terrestrial omega-3 sources such as flaxseeds, avocados, and walnuts. Plant sources of omega-3 fatty acids include flaxseed, oils (olive, canola, flaxseed, soybean), nuts and other seeds (walnuts, butternut squash and sunflower). Replacements for vegans/vegetarians exist that are not supplements, but the evidence is not as robust for plant sources of omega-3 fatty acids.

- Berries. Researchers credit the high levels of flavonoids in berries with the benefit 98. Flavonoids, the natural plant pigments that give berries their brilliant hues, also help improve memory, research shows. Berries contain a particularly high amount of flavonoids called anthocyanidins that are capable of crossing the blood brain barrier and localizing themselves in the hippocampus, an area of the brain known for memory and learning. Epidemiological evidence has established strong inverse associations between flavonoid-rich fruit (e.g. strawberries, grapefruit) and coronary heart disease mortality in cardiovascular disease-free postmenopausal women after multivariate adjustment 99. In a 20-year study of over 16,000 older adult women (aged ≥70 years), those who ate the most blueberries and strawberries had the slowest rates of cognitive decline by up to two-and-a-half years 98.

- Walnuts. Nuts are excellent sources of protein, fat-soluble vitamin E and healthy fats, and one type of nut in particular might also improve memory. A 2015 study from UCLA linked higher walnut consumption to improved cognitive test scores. Walnuts are high in a type of omega-3 fatty acid called alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). Diets rich in alpha-linolenic acid and other omega-3 fatty acids have been linked to lower blood pressure and cleaner arteries. That’s good for both the heart and brain.

- Meat-free meals. Heart-healthy eating encourages consuming meat sparingly. Beans, lentils and soybeans, which pack protein and fiber, make a worthy substitute. They’ll keep you full and are rich in B vitamins, which are important for brain health. In one study analyzing the diets of older adults, those who had the lowest intakes of legumes had greater cognitive decline than those who ate more.

The American Heart Association suggests these daily amounts:

- Vegetables – canned, dried, fresh and frozen vegetables; 5 servings

- Fruits – canned, dried, fresh and frozen fruits; 4 servings

- Whole grains – barley, brown rice, millet, oatmeal, popcorn and whole wheat bread, crackers and pasta; 3-6 servings

- Dairy – low fat (1%) and fat-free dairy products; 3 servings

- Proteins – eggs, fish, lean meat, legumes, nuts, poultry and seeds; 1-2 servings. Eat a variety of fish at least twice a week, especially fish containing omega-3 fatty acids (for example, salmon, trout and herring).

- Oils – polyunsaturated and monounsaturated canola, olive, peanut, safflower and sesame oil; 3 tablespoons

- Limit – sugary drinks, sweets, fatty meats, and salty or highly processed foods

- Choose foods with less salt (sodium) and prepare foods with little or no salt. To lower blood pressure, aim to eat no more than 2,300 milligrams of sodium per day. Reducing daily intake to 1,500 mg is desirable because it can lower blood pressure even further.

- Limit saturated fat and trans fat and replace them with the better fats, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated. If you need to lower your blood cholesterol, reduce saturated fat to no more than 5 to 6 percent of total calories. For someone eating 2,000 calories a day, that’s about 13 grams of saturated fat.

- Avoid – partially hydrogenated oils, tropical oils, and excessive calories

- Replace – highly processed foods with homemade or less-processed options

- If you drink alcohol, drink in moderation. That means no more than one drink per day if you’re a woman and no more than two drinks per day if you’re a man.

Carbohydrate

Carbohydrate (starch) is the body’s main energy (fuel) source. Starch is broken down to produce glucose which is used by your body for energy.

Starchy foods are an important part of the healthy diet. They should make up about a third of all the food that you eat. You don’t have to avoid or restrict them because they are ‘fattening’. Instead, be aware of the total amount of starch that you eat. Cutting out one food group, such as carbohydrate can cause dietary imbalance. Starchy foods include bread, potatoes, rice and pasta. Wholegrain options are healthier choices.

Fiber rich foods help your gut to function properly and have many other health benefits. Studies have shown that people who are overweight or obese tend to lose weight if they include plenty of high fiber, starchy carbohydrate in their diets.

Sugar

Sugar is a type of carbohydrate. Like starch, it breaks down into glucose, to provide energy for your body. ‘Free’ sugars are often added to foods during manufacture and include refined sugars such as sucrose (table sugar). This kind of sugar is also found naturally, in unsweetened fruit juices, and in syrups and honey.

Excess consumption of free sugars is linked to the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and tooth decay. Many of the free sugars that you consume, are in sugary drinks. A regular can of cola for instance, can contain the equivalent of seven teaspoons of sugar (35g). The guidance about free sugar consumption suggests a daily limit of 30g. This is equivalent to six teaspoons.

The natural sugars found in milk and in whole fruits and vegetables are not free sugars and do not need to be restricted in the same way.

Fruit and vegetables

Fruit and vegetables contain high levels of ‘micronutrients’. These include vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. Micronutrients are essential to the body’s many biochemical processes.

Fruit and vegetables are often high in fiber. They are generally low in calorie and they taste good. The current Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends at least five portions of different fruit and vegetable per day 100. Like carbohydrate, fruit and vegetable should account for about one third of what you eat, per day. Dried, frozen, tinned, as well as fresh, fruit and veg are all included. One portion of pulses (baked beans, lentils, dried peas) can also count towards your five a day.

Dietary fiber

Fiber comes from plant-based foods, including fruits, vegetables and wholegrains. Dietary fiber is the part of plants that you eat but which doesn’t get digested in your small intestine. Instead, it is completely or partially broken down (fermented) by bacteria in your large intestine. Once broken down in your large intestine, it has been suggested that dietary fibers increase the beneficial bacteria in your gut. This improves your immune system. Fibre includes carbohydrates called polysaccharides and resistant oligosaccharides. Recent research suggests that fiber should be categorized by its physical characteristics; how well it dissolves (solubility), how thick it is (viscosity) and how well it breaks down (fermentability). Some commonly known terms are described below:

- Soluble fiber including pectins and beta glucans is found in foods like fruit and oats.

- Insoluble fiber including cellulose is found in wheat bran and nuts.

- Resistant starch is a soluble fiber that is highly fermentable in the gut. It gets broken down by good bacteria to produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Resistant starch is naturally present in some foods such as bananas, potatoes, grains and pulses.

- Prebiotics are types of carbohydrate that only our gut bacteria can feed upon. Some examples are onions, garlic, asparagus and banana

Fibre is essential for your gut to work normally. It increases good bacteria which supports your immunity against inflammatory disorders and allergies. A high fiber diet seems to reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and bowel cancer.

Eating a range of dietary fiber can:

- Improve the diversity of your microbiota

- Improve constipation and lactose intolerance

- Enhance immunity

- Reduce inflammation in your gut

For example, high quality randomized controlled trials have shown that eating oat bran leads to lower blood pressure and lower total cholesterol.

Benefits of a high-fiber diet:

- Normalizes bowel movements. Dietary fiber increases the weight and size of your stool and softens it. A bulky stool is easier to pass, decreasing your chance of constipation. If you have loose, watery stools, fiber may help to solidify the stool because it absorbs water and adds bulk to stool.

- Helps maintain bowel health. A high-fiber diet may lower your risk of developing hemorrhoids and small pouches in your colon (diverticular disease). Studies have also found that a high-fiber diet likely lowers the risk of colorectal cancer. Some fiber is fermented in the colon. Researchers are looking at how this may play a role in preventing diseases of the colon.

- Lowers cholesterol levels. Soluble fiber found in beans, oats, flaxseed and oat bran may help lower total blood cholesterol levels by lowering low-density lipoprotein, or “bad,” cholesterol levels. Studies also have shown that high-fiber foods may have other heart-health benefits, such as reducing blood pressure and inflammation.

- Helps control blood sugar levels. In people with diabetes, fiber — particularly soluble fiber — can slow the absorption of sugar and help improve blood sugar levels. A healthy diet that includes insoluble fiber may also reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

- Aids in achieving healthy weight. High-fiber foods tend to be more filling than low-fiber foods, so you’re likely to eat less and stay satisfied longer. And high-fiber foods tend to take longer to eat and to be less “energy dense,” which means they have fewer calories for the same volume of food.

- Helps you live longer. Studies suggest that increasing your dietary fiber intake — especially cereal fiber — is associated with a reduced risk of dying from cardiovascular disease and all cancers.

Good sources of dietary fiber include:

- Pulses (like lentils and peas) and beans and legumes (think navy beans, small white beans, split peas, chickpeas, lentils, pinto beans)

- Fruits and vegetables, vegetables such as carrots, broccoli, green peas, and collard greens; fruits especially those with edible skin (like pears and apples with the skin on) and those with edible seeds (like berries)

- Nuts—try different kinds (pumpkin seeds, almonds, sunflower seeds, pistachios and peanuts are a good source of fiber and healthy fats, but be mindful of portion sizes, because they also contain a lot of calories in a small amount!)

- Whole grains such as:

- Quinoa, barley, bulgur, oats, brown rice and farro

- Whole wheat pasta

- Whole grain cereals, including those made from whole wheat, wheat bran and oats

Choose fiber rich foods from a variety of sources including wholegrains, fruit and vegetable, nuts and seeds, beans and pulses. When you read food labels check for the grams of fiber per serving or per 100g. Foods that are naturally high in fiber and contain at least 3 grams per 100 gram are often labeled as a “good source,” and foods labeled as “excellent source” contain more than 5 grams of fiber per serving.

Depending on your age and sex, adults should get 25 to 31 grams of fiber a day 101. Older adults sometimes don’t get enough fiber because they may lose interest in food.

- Men over the age of 50 should get at least 38 grams of fiber per day.

- Women over the age of 50 should get 25 grams per day.

- Children ages 1 to 3 should get 19 grams of fiber per day.

- Children between 4 and 8 years old should get 25 grams per day.

- Girls between 9 and 18 should get 26 grams of fiber each day. Boys of the same age range should get between 31 and 38 grams of fiber per day.

You may wish to see a dietitian if you:

- are unsure about how much and/or what types of fiber you currently have in your diet

- suffer with constipation or diarrhea (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome [IBS])

- have a condition which can restrict your fiber intake (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease)

Keep in mind that if you haven’t been eating a lot of foods high in fiber on a daily basis, it’s important to increase your intake slowly to allow your body to adjust. A sudden increase in eating foods high in fiber (especially foods with added fiber or when using supplements) can cause gas, bloating or constipation. Be sure you are drinking enough water too, because fiber needs water to move through your body.

Protein

Protein is vital. It is your body’s main building block. Animal products such as meat, fish, eggs and dairy are good sources of dietary protein. Meat and fish also provide your body with a form of iron (heme), which is easy to absorb. Fish also contains essential fatty acids (e.g, Omega-3).

Protein also comes from foods of plant origin. Pulses, nuts, and seeds are all high in protein. Pulses are a very good meat alternative, whether or not you are vegetarian or vegan.

Cutting back on consumption of red meat (beef, lamb, goat, pork) especially, is better for your health and for the environment: current advice is to have no more than 300g of red meat per week. Try to avoid processed meats such as bacon, salami, hot dogs, ham. Consumption of these cured meat products has been linked to a much higher risk of certain gut cancers.

Dairy

Dairy products and calcium-fortified alternatives are your body’s main source of calcium, which is necessary for the growth, development and maintenance of healthy bones and teeth. Dairy products and alternatives are also a source of protein. Milk, cheese, cream and milk-based sauces and yogurts can have a high saturated fat content. Fat reduced options are recommended, and small quantities.

Fats

Fats also known as lipids, is an essential nutrient (a primary storage form of energy, a kilojoule-dense nutrient) your body need for energy and to help your gut absorb vitamins A, D, E and K from foods. Fat has twice as many calories as proteins or carbohydrates. There are nine calories (37kJ) in every gram of fat, regardless of what type of fat it is. Fats are more energy-dense than carbohydrates and proteins, which provide four calories (17kJ) per gram. Dietary fat also plays a major role in your cholesterol levels. You need some fat in your diet but not too much. There are different types of fats, some are “good” and some are “bad”, however, you should try to avoid “bad” fats. When it comes to dietary fat, what matters most is the type of fat you eat. Contrary to past dietary advice promoting low-fat diets, newer research shows that healthy fats are necessary and beneficial for health.

Healthy fats are unsaturated. They keep cholesterol levels within a healthy range, reduce your risk of heart problems and may be good for the skin, eyes and brain. Unsaturated fats are the best choice for a healthy diet.

Unhealthy fats are saturated and trans fats, which can raise levels of ‘bad’ cholesterol and increase the risk of heart disease. Multiple studies have linked high levels of saturated fat with cognitive decline. A diet that is higher in unsaturated fats and lower in saturated fats is linked to better cognition.

- Saturated fats such as butter, solid shortening, and lard. Eating foods that contain saturated fats raises the level of cholesterol in your blood. High levels of LDL cholesterol (low-density lipoprotein or “bad” cholesterol) in your blood increase your risk of heart disease and stroke. The American Heart Association recommends aiming for a dietary pattern that achieves 5% to 6% of calories from saturated fat. For example, if you need about 2,000 calories a day, no more than 120 of them should come from saturated fat. That’s about 13 grams of saturated fat per day 102.

- Trans fats also known as trans fatty acids or “partially hydrogenated oils”. These are found in vegetable shortenings, some margarines, crackers, cookies, snack foods, and other foods made with or fried in partially hydrogenated oils. By 2018, most U.S. companies will not be allowed to add partially hydrogenated oils to food.

“Bad” fats, such as artificial trans fats and saturated fats, are guilty of the unhealthy things all fats have been blamed for—weight gain, clogged arteries, an increased risk of certain diseases, and so forth. Large studies have found that replacing saturated fats in your diet with unsaturated fats and omega-3 fatty acids can reduce your risk of heart disease by about the same amount as cholesterol-lowering drugs. Since fat is an important part of a healthy diet, rather than adopting a low-fat diet, it’s more important to focus on eating more beneficial “good” fats and limiting harmful “bad” fats. For good health, the majority of the fats that you eat should be monounsaturated or polyunsaturated. Eat foods containing monounsaturated fats and/or polyunsaturated fats such as canola oil, olive oil, safflower oil, sesame oil or sunflower oil instead of foods that contain saturated fats and/or trans fats.

For years you’ve been told that eating fat will add inches to your waistline, raise cholesterol, and cause a myriad of health problems. When food manufacturers reduce fat, they often replace it with carbohydrates from sugar, refined grains, or other starches. Your body digests these refined carbohydrates and starches very quickly, affecting your blood sugar and insulin levels and possibly resulting in weight gain and disease 103. But now scientists know that not all fat is the same. Research has shown that unsaturated fats are good for you. Healthy fats play a huge role in helping you manage your moods, stay on top of your mental game, fight fatigue, and even control your weight. These fats come mostly from plant sources. Cooking oils that are liquid at room temperature, such as canola, peanut, safflower, soybean, and olive oil, contain mostly unsaturated fat. Nuts, seeds, and avocados are also good sources. Fatty fish—such as salmon, sardines, and herring—are rich in unsaturated fats, too. You should actively make unsaturated fats a part of your diet. Of course, eating too much fat will put on the pounds too. Note also that by swapping animal fats for refined carbohydrates—such as replacing your breakfast bacon with a bagel or pastry—won’t have the same benefits. In fact eating refined carbohydrates or sugary foods can have a similar negative effect on your cholesterol levels, your risk for heart disease, and your weight. Limiting your intake of saturated fat can still help improve your health—as long as you take care to replace it with good fat rather than refined carbs. In other words, don’t go no fat, go good fat.

Healthy-eating tips:

- Use olive oil in cooking.

- Replace saturated fats with unsaturated fats; for example, use avocado, tahini, nut or seed butter instead of dairy butter.

- Eat fish, especially oily fish, twice a week.

- Consume legume- or bean-based meals twice a week.

- Snack on nuts or add them to your cooking.

- Throw avocado in salads.

- Choose lean meats and trim any fat you can see (including chicken skin).

- Use table spreads that have less than 0.1g of trans fats per 100g.

Saturated fats

Saturated fats are fat molecules that are “saturated” with hydrogen molecules. Saturated fats are normally solid at room temperature. Saturated fats occur naturally in many foods — primarily meat and dairy foods (butter, cream, full-fat milk and cheese). Beef, lamb, pork on poultry (with the skin on) contain saturated fats, as do butter, cream and cheese made from whole or 2% milk. Plant-based foods that contain saturated fats include coconut, coconut oil, coconut milk and coconut cream, cooking margarine, and cocoa butter, as well as palm oil and palm kernel oil (often called tropical oils). Saturated fats are also found in snacks like chips, cakes, biscuits and pastries, and takeaway foods. Consuming more than the recommended amount of saturated fat is linked to heart disease and high cholesterol.

The American Dietary Guidelines recommend that:

- men should not eat more than 30g of saturated fat a day

- women should not eat more than 20g of saturated fat a day

- children should have less

For people who need to lower their cholesterol, the American Heart Association recommends reducing saturated fat to less than 6% of total daily calories. For someone eating 2,000 calories a day, that’s about 11 to 13 grams of saturated fat 102.

Examples of foods with saturated fat are:

- fatty beef,

- lamb,

- pork,

- poultry with skin,

- beef fat (tallow),

- meat products including sausages and pies,

- lard and cream,

- butter and ghee,

- cheese especially hard cheese like cheddar,

- other dairy products made from whole or reduced-fat (2 percent) milk,

- cream, soured cream and ice cream,

- some savory snacks, like cheese crackers and some popcorns,

- chocolate confectionery,

- biscuits, cakes, and pastries

In addition, many baked goods and fried foods can contain high levels of saturated fats. Some plant-based oils, such as palm oil, palm kernel oil, coconut oil and coconut cream, also contain primarily saturated fats, but do not contain cholesterol.

Unsaturated Fats

If you want to reduce your risk of heart disease, it’s best to reduce your overall fat intake and swap saturated fats for unsaturated fats. Unsaturated fats are in fish, such as salmon, trout and herring, and plant-based foods such as avocados, olives and walnuts. Liquid vegetable oils, such as soybean, corn, safflower, canola, olive and sunflower, also contain unsaturated fats.

There are 2 types of unsaturated fats: monounsaturated and polyunsaturated. Unsaturated fats help reduce your risk of heart disease and lower your cholesterol levels.

- Polyunsaturated fats such as omega-3 and omega-6 fats are found in fish, nuts, and safflower and soybean oil.

- Monounsaturated fats are found in olive and canola oil, avocado, cashews and almonds.

Monounsaturated fats have one (“mono”) unsaturated carbon bond in the molecule. Polyunsaturated fats have more than one (“poly,” for many) unsaturated carbon bonds. Both of these unsaturated fats are typically liquid at room temperature.

Eaten in moderation, both kinds of unsaturated fats may help improve your blood cholesterol when used in place of saturated and trans fats.

Polyunsaturated fats

Polyunsaturated fats are simply fat molecules that have more than one unsaturated carbon bond in the molecule, this is also called a double bond. Oils that contain polyunsaturated fats are typically liquid at room temperature but start to turn solid when chilled. Olive oil is an example of a type of oil that contains polyunsaturated fats.

There are 2 main types of polyunsaturated fats: omega-3 and omega-6. Oils rich in polyunsaturated fats also provide essential fats that your body needs but can’t produce itself – such as omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. You must get essential fats through food. Omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids are important for many functions in the body. A deficiency of essential fatty acids—either omega-3s or omega-6s—can cause rough, scaly skin and dermatitis 104.

Polyunsaturated fats can help reduce bad cholesterol levels in your blood which can lower your risk of heart disease and stroke. Polyunsaturated fats also provide nutrients to help develop and maintain your body’s cells. Oils rich in polyunsaturated fats also contribute vitamin E to the diet, an antioxidant vitamin most Americans need more of.

Foods high in polyunsaturated fat include a number of plant-based oils, including:

- soybean oil

- corn oil

- sunflower oil

Other sources include some nuts and seeds such as walnuts and sunflower seeds, tofu and soybeans.

Omega-6 fats are found in vegetable oils, such as:

- rapeseed

- corn

- sunflower

- some nuts

Omega-3 fats are found in oily fish, such as:

- kippers

- herring

- trout

- sardines

- salmon

- mackerel

The American Heart Association also recommends eating tofu and other forms of soybeans, canola, walnut and flaxseed, and their oils. These foods contain alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), another omega-3 fatty acid.

Polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) are frequently designated by their number of carbon atoms and double bonds. Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), for example, is known as C18:3n-3 because it has 18 carbons and 3 double bonds and is an omega-3 fatty acid. Similarly, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) is known as C20:5n-3 and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) as C22:6n-3. Omega-6 fatty acids (omega-6s) have a carbon–carbon double bond that is six carbons away from the methyl end of the fatty acid chain. Linoleic acid (LA) known as C18:2n-6 and arachidonic acid (AA) known as C20:4n-6 are two of the major omega-6s.

The human body can only form carbon–carbon double bonds after the 9th carbon from the methyl end of a fatty acid 105. Therefore, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) and linoleic acid (LA) are considered essential fatty acids, meaning that they must be obtained from the diet 106. Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) can be converted into eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and then to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), but the conversion (which occurs primarily in the liver) is very limited, with reported rates of less than 15% 107. Therefore, consuming EPA and DHA directly from foods and/or dietary supplements is the only practical way to increase levels of these fatty acids in the body.

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) is present in plant oils, such as flaxseed, soybean, and canola oils 107. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) are present in fish, fish oils, and krill oils, but they are originally synthesized by microalgae, not by the fish. When fish consume phytoplankton that consumed microalgae, they accumulate the omega-3s in their tissues 107.

Some researchers propose that the relative intakes of omega-6s and omega-3s—the omega-6/omega-3 ratio—may have important implications for the pathogenesis of many chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer 108, but the optimal ratio—if any—has not been defined 109. Others have concluded that such ratios are too non-specific and are insensitive to individual fatty acid levels 110. Most agree that raising eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) blood levels is far more important than lowering linoleic acid (LA) or arachidonic acid levels.