What is thyroid cartilage

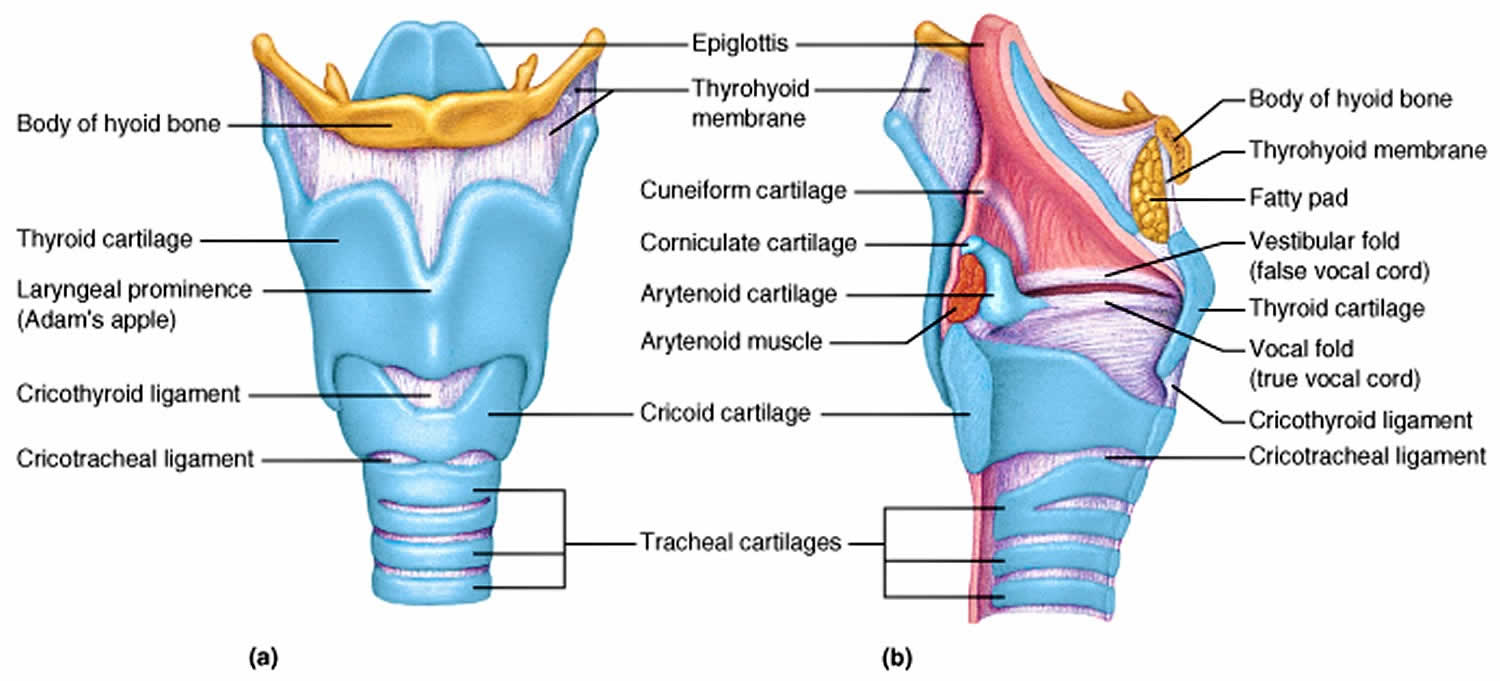

Thyroid cartilage is the largest of nine cartilages in the of the human larynx. Thyroid cartilage is named for its shield-shaped rather than for its proximity to the thyroid gland and has two lateral laminae which join anteriorly to form the U-shaped cartilaginous protuberance on the front of the neck colloquial term the “Adam’s apple” (which is more prominent in males), what is officially named the laryngeal prominence of the thyroid cartilage and is articulated below to the ring-like cricoid cartilage. In females, the sides join at an angle of approximately 120 degrees. In man the lateral laminae meet anteriorly at a sharp angle (the angle is closer to 90 degrees), forming Adam’s apple. This smaller thyroid angle explains the greater laryngeal prominence (“Adam’s apple”), longer vocal cords, and lower-pitched voice in males. The dorsal edges of the laminae lie well apart, and are extended anteriorly and posteriorly by the greater and lesser horns of the cartilage. The posterior horn articulates with the upper, lateral and surface of the cricoid cartilage via a synovial joint. The long anterior horns pass medial to, and are attached to, the posterior horns (usually called cornua; cornu=horn) of the hyoid bone. In man the greater horns of the thyroid cartilage are attached to the tips of the equivalent greater cornua of the hyoid by the thyrohyoid ligaments, which form the posterior edges of the large thyrohyoid membrane.

Thyroid cartilage is one of the most significant external landmarks in the neck and is very useful for anatomical orientation in procedures such as cricothyroidotomies. Thyroid cartilage is notably more prominent in men than women and primarily acts to protect the vocal cords posteriorly. The classic measurement of the interlaminar angle at the level of the vocal processes is 90 degrees in the male population, and 120 in females. The broader angle in women causes it to protrudes less, not push up against the skin of the neck, and ultimately be less visible.

Thyroid cartilage function

The thyroid cartilage forms the bulk of the front wall of the larynx and primarily acts to protect the vocal cords immediately behind it. The thyroid cartilage also serves as an attachment for several muscles. Thyroid cartilage is a secondary sexual characteristic: meaning it appears around the time of puberty and helps distinguish between the sexes, as it is more prominent in men than it is in women. The swelling of the laryngeal prominence takes place during puberty and is logically thought to play a role in the voice mutation that also occurs in this period. However, no work has yet been done to prove this relationship decisively, only small reports of cadaver studies 1. When the angle of the thyroid cartilage changes relative to the cricoid cartilage, this changes the pitch of voice.

Thyroid cartilage fracture

Acute laryngeal trauma is estimated to occur in approximately one patient per 14,500 to 42,500 emergency room admissions 2. If the larynx is injured, its vital functions are affected and can be threatened in case of severe injury. When laryngeal fractures occur, stenosis and deformity may occur in the airway and vocal tract unless proper repair is undertaken. The importance of restoring this normal laryngeal framework configuration has been demonstrated in earlier studies 3.

The most effective approach in repairing laryngeal fracture remains controversial, and little research has addressed the subject directly 2.

Traditionally, laryngeal fractures have been repaired with stainless steel wire or sutures 4. Woo 4 reported on his success using miniplates for laryngeal reconstruction. His stated advantage of miniplates fixation was the immediate and sustained rigid stability of the framework with restoration of the laryngeal airway.

Hirano et al 5 have recommended the use of vocal function tests preoperatively and postoperatively in assessing the impact of the laryngeal trauma on the voice function.

In the past, different methods of repair have been described such as the use of non-restorable sutures, stainless steel wires and endolaryngeal stents. The main disadvantage of these traditional techniques is that they fail to achieve accurate three-dimensional reduction and stable fixation of the fractured cartilage 6. Schaefer and Close recommended open repair for all displaced fractures 7.

Studies from the 1990s, reflecting techniques preceding miniplates, report that a good laryngeal airway was achieved in over 90% but a good voice in only 70%, as discussed by Jewett et al 8.

An interesting rabbit study by Dray et al 9 found cartilaginous healing of fractures fixed with plates, but fibrous healing in those fixed with wire. de Mello-Filho and Carrau 10 reviewed 20 patients who have had repairs of laryngeal fractures with miniplates. They reported that 19 of the 20 patients had a good airway, recovered their voice and were able to swallow without aspiration.

Reconstruction screws can be used in thyroid cartilage, and its fixation strength is maximized by larger screw/screw hole ratios than in bone 11. Maximum strength is achieved using a 1.5 mm titanium adaption screw in a 0.76 mm drill hole.

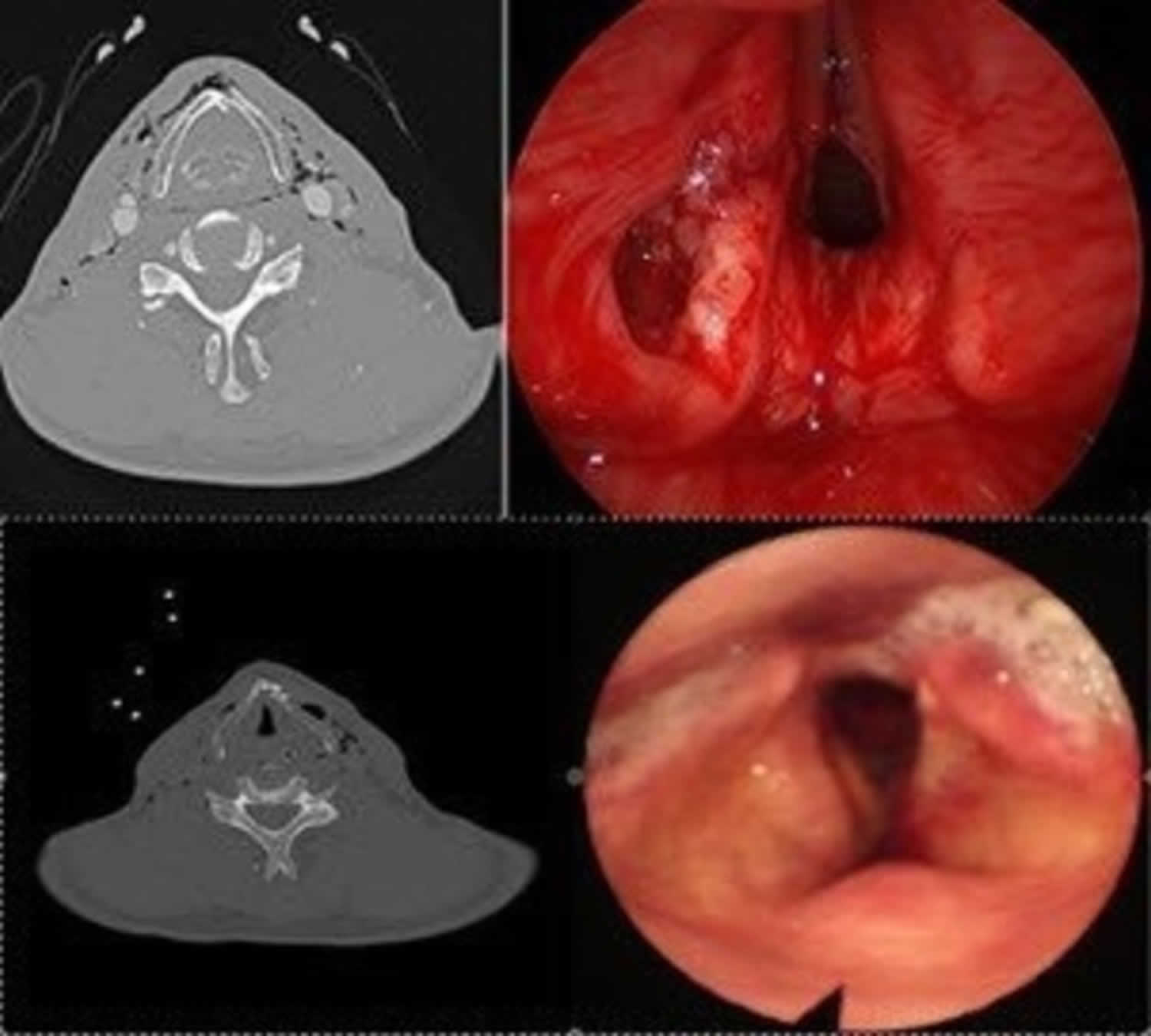

Figure 1. Thyroid cartilage fracture

Footnote: (Top) Preoperative CT scan and fiber endoscopic examination show a displaced fracture of the thyroid cartilage on the left side with extensive emphysema and a laceration of the mucosa. (Bottom) Postoperative CT scan and 1-month postoperative fiber endoscopic examination show symmetric alignment of the thyroid cartilage with regression of the emphysema and good healing of the laryngeal mucosa with normal vocal fold mobility and no endo-laryngeal exposure of the miniplates or screws.

[Source 2 ] References- Glikson E, Sagiv D, Eyal A, Wolf M, Primov-Fever A. The anatomical evolution of the thyroid cartilage from childhood to adulthood: A computed tomography evaluation. Laryngoscope. 2017 Oct;127(10):E354-E358

- Hallak B, Von Wihl S, Boselie F, Bouayed S. Repair of displaced thyroid cartilage fracture using miniplate osteosynthesis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11(1):e226677. Published 2018 Dec 7. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-226677 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6301512

- Stanley RB, Cooper DS, Florman SH. Phonatory effects of thyroid cartilage fractures. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1987;96:493–6. 10.1177/000348948709600503

- Woo P. Laryngeal framework reconstruction with miniplates. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1990;99:772–7. 10.1177/000348949009901003

- Hirano M, Kurita S, Terasawa R. Difficulty in high-pitched phonation by laryngeal trauma. Arch Otolaryngol 1985;111:59–61. 10.1001/archotol.1985.00800030093015

- Islam S, Shorafa M, Hoffman GR, et al. Internal fixation of comminuted cartilaginous fracture of the larynx with mini-plates. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;45:321–2. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.11.015

- Schaefer SD, Close LG. Acute management of laryngeal trauma. Update. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1989;98:98–104. 10.1177/000348948909800203

- Jewett BS, Shockley WW, Rutledge R. External laryngeal trauma analysis of 392 patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125:877–80. 10.1001/archotol.125.8.877

- Dray TG, Coltrera MD, Pinczower EF. Thyroid cartilage fracture repair in rabbits: comparing healing with wire and miniplate fixation. Laryngoscope 1999;109:118–22. 10.1097/00005537-199901000-00023

- de Mello-Filho FV, Carrau RL. The management of laryngeal fractures using internal fixation. Laryngoscope 2000;110:2143–6. 10.1097/00005537-200012000-00032

- Plant RL, Pinczower EF. Pullout strength of adaption screws in thyroid cartilage. Am J Otolaryngol 1998;19:154–7. 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90080-1