What is tricuspid regurgitation

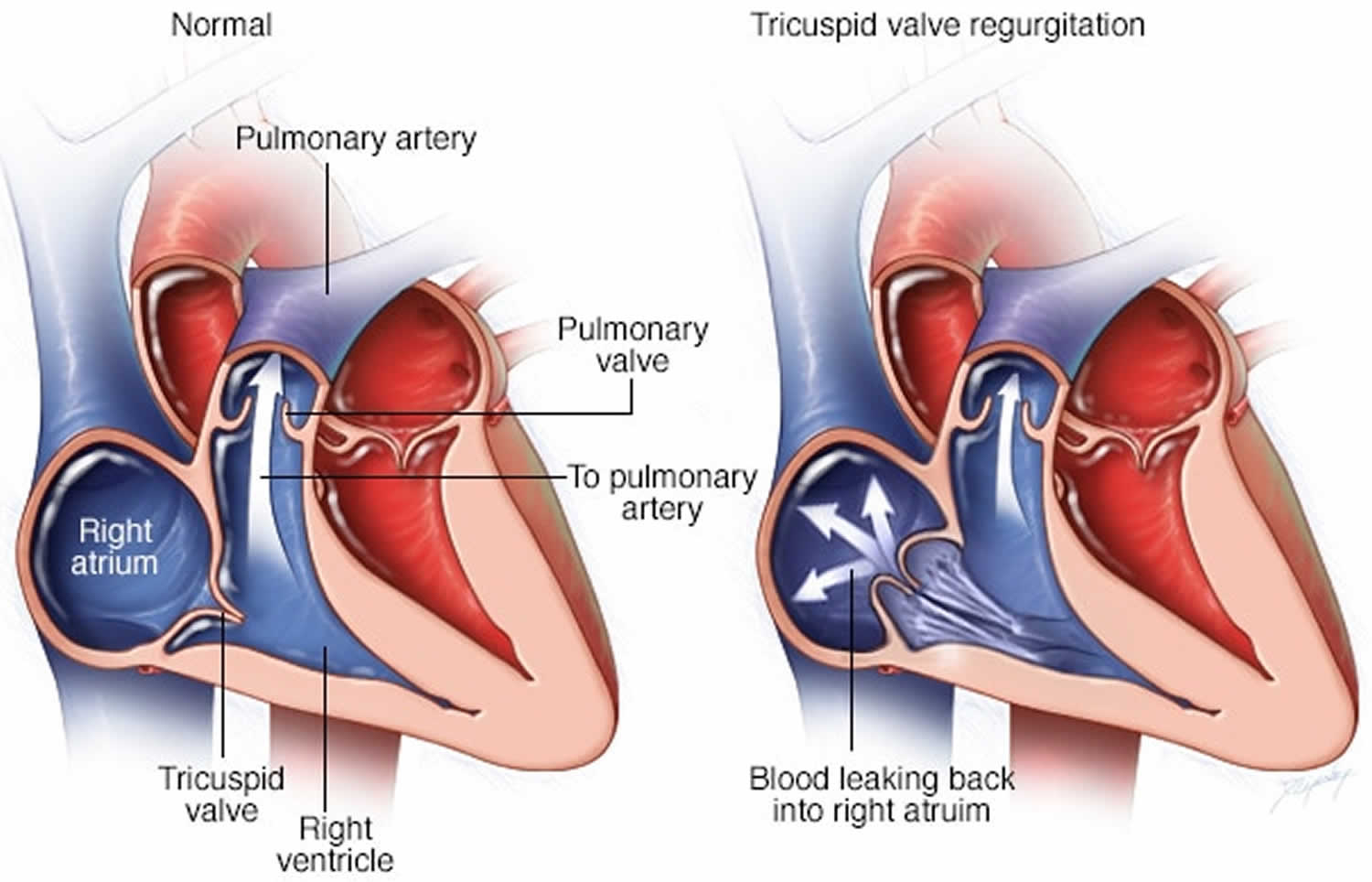

Tricuspid valve regurgitation is also known as tricuspid valve insufficiency or tricuspid valve incompetence, is leakage of blood backwards through the tricuspid valve each time the right ventricle contracts. Tricuspid regurgitation is a disorder in which the tricuspid valve does not close tight enough. The tricuspid valve separates the right lower heart chamber (the right ventricle) from the right upper heart chamber (right atrium). As the right ventricle contracts to pump blood forward to the lungs, some blood leaks backward into the right atrium, increasing the volume of blood in the atrium. As a result, the right atrium can enlarge, which can change the pressure in the nearby chambers and blood vessels.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation can be the result of a condition you’re born with (congenital heart disease) or it can occur due damage to the tricuspid heart valve or enlargement of the right ventricle. However, the most common cause of tricuspid regurgitation is not damage to the valve itself but enlargement of the right ventricle, which may be a complication of any disorder that causes right ventricular failure.

Treatment may not be needed if your condition is mild or you have no symptoms. Your doctor may just monitor your condition.

However, if you have severe tricuspid valve regurgitation and you’re experiencing signs and symptoms, treatment may be necessary. You may need to go to the hospital to diagnose and treat severe symptoms.

Surgical valve repair or replacement most often provides a cure in people who need an intervention.

The outlook is poor for people who have symptomatic, severe tricuspid regurgitation that cannot be corrected.

How common is mild tricuspid regurgitation?

The incidence of tricuspid regurgitation in the United States is found to be 0.9% 1. No gender or racial differences in the incidences are noted.

Tricuspid regurgitation presents at different age groups depending on its etiology. Ebstein anomaly may be diagnosed at birth and during early childhood. Rheumatic valvular disease is the most common form of tricuspid regurgitation in patients older than 15 years.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation and exercise

It’s a good idea to stay physically active. Your doctor may give you recommendations about how much and what type of exercise is appropriate for you.

How the heart works

Your heart, the center of your circulatory system, is made up of four chambers. The two upper chambers (atria) receive blood. The two lower chambers (ventricles) pump blood.

Four heart valves open and close to let blood flow in one direction through your heart. The tricuspid valve — which lies between the two chambers on the right side of your heart — consists of three flaps of tissue called leaflets.

The tricuspid valve opens when blood flows from the right atrium to the right ventricle. Then the flaps close to prevent the blood that has just passed into the right ventricle from flowing backward.

In tricuspid valve regurgitation, the tricuspid valve doesn’t close tightly. This causes the blood to flow back into the right atrium during each heartbeat.

Figure 1. Heart valves anatomy

Figure 3. Tricuspid valve regurgitation

Tricuspid regurgitation severity

The echocardiographic detection of tricuspid regurgitation is common, and present in approximately 70% of people. For pathological tricuspid regurgitation, various parameters are used in order to determine severity, such as 2:

Mild tricuspid regurgitation

- tricuspid valve normal

- right ventricular or right atrial or inferior vena caval size normal

- central jet <5 cm²

- regurgitant volume not defined

- vena contracta not defined

- proximal isovelocity surface area radius ≤0.5 cm

- jet density and contour is soft and parabolic

- hepatic vein flow has systolic dominance

Moderate tricuspid regurgitation

- tricuspid valve may be normal or abnormal

- right ventricular or right atrial or inferior vena caval size may be normal or abnormal

- central jet 5-10 cm²

- regurgitant volume not defined

- vena contracta not defined but <0.7 cm

- proximal isovelocity surface area radius 0.6-0.9 cm

- jet density and contour is dense with a variable contour

- hepatic vein flow has systolic blunting

- a pattern consisting of a pulsatile waveform with prominent V waves, decreased S wave amplitude, and reversal of the S/D ratio is specific for tricuspid regurgitation

Severe tricuspid regurgitation

- tricuspid valve is abnormal with a flail leaflet

- right ventricular or right atrial or inferior vena caval size usually dilated

- central jet >10 cm²

- regurgitant volume ≥45 mL

- vena contracta >0.7 cm

- proximal isovelocity surface area radius >0.9 cm

- jet density and contour is dense and triangular with early peaking

- E-wave velocity > 1 m/s

- hepatic vein flow has systolic reversal

- characteristic inversion of the S wave and fusion with the a and v waves will form a characteristic a-S-v complex 3

Additionally, the shape of the tricuspid annulus can alter with regurgitation 4. A normal annulus has a bimodal shape with distinct high points located anteroposteriorly and low points located mediolaterally 8. With functional tricuspid regurgitation, the annulus can become larger, more planar, and circular 5.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation causes

In a majority of patients (70-85%), the tricuspid regurgitation is considered ‘functional’ (or ‘secondary’), where it is caused by dilatation of the annulus as a result of increased pulmonary and right ventricular pressures 6. In the remaining 15–30% of patients, it may be organic (or ‘primary’) and related to direct involvement of the tricuspid valve 6. Furthermore, tricuspid regurgitation in isolation is very rare; it is more often found in association other valvular disease, especially mitral valve disease 7.

An increase in size of the right ventricle is the most common cause of tricuspid valve regurgitation. The right ventricle pumps blood to the lungs where it picks up oxygen. Any condition that puts extra strain on the right ventricle can cause it to enlarge. Several conditions that affect the right ventricle, such as heart failure; conditions that cause high blood pressure in the arteries in your lungs (pulmonary hypertension); or an abnormal heart muscle condition (cardiomyopathy) also may cause the tricuspid valve to stop working properly. Examples include:

- Abnormally high blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs which can come from a lung problem (such as COPD, or a clot that has traveled to the lungs)

- Other heart problem such as poor squeezing of the left side of the heart

- Problem with the opening or closing of another one of the heart valves

Tricuspid valve regurgitation can also occur with heart conditions that affect the left side of the heart, such as left-sided heart failure that leads to right-sided heart failure.

Causes of organic (primary) tricuspid regurgitation include 8:

- Congenital abnormalities (e.g. Ebstein anomaly). Ebstein’s anomaly. In this rare condition, the malformed tricuspid valve sits lower than normal in the right ventricle, and the tricuspid valve’s leaflets are abnormally formed. The posterior and the septal leaflets of the tricuspid valve are displaced apically in the right ventricle resulting in its atrialization. This can lead to blood leaking backward (regurgitating) into the right atrium. Tricuspid valve regurgitation in children is usually caused by heart disease present at birth (congenital heart disease). Ebstein’s anomaly is the most common congenital heart disease that causes the condition. Tricuspid valve regurgitation in children may often be overlooked and not diagnosed until adulthood.

- Direct factors affecting the tricuspid valve

- Myxomatous degeneration associated with tricuspid valve prolapse, which occurs in as many as 40% of patients with prolapse of the mitral valve

- Infective endocarditis. The tricuspid valve may be damaged by an infection of the lining of the heart (infective endocarditis) that can involve heart valves. Intravenous drug use, neoplasms, alcoholism, extensive burns, infected indwelling catheters, and immune deficiency causes infection of the valve. An annular abscess is common.

- Rheumatic heart disease (Rheumatic fever). Rheumatic fever is a complication of untreated strep throat that can damage heart valves, including the tricuspid valve, leading to tricuspid valve regurgitation later in life. The valves undergo fibrous thickening without commissural fusion, fused chordae, or calcific deposits.

- Valve dysfunction due to myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Chest wall or deceleration injury trauma.

- Valve disruption from trauma. Implantable device wires (leads). Pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator wires can sometimes cause injury to the tricuspid valve during placement or removal of the implantable device.

- Endomyocardial biopsy. In an endomyocardial biopsy, a small amount of heart muscle tissue is removed and tested for signs of inflammation or infection. Valve damage can sometimes occur during this procedure.

- Blunt chest trauma. Experiencing trauma to your chest, such as in a car accident, can lead to tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Carcinoid tumors (carcinoid syndrome), which release a hormone that damages the valve. In this rare condition, tumors that develop in your digestive system and spread to your liver or lymph nodes produce a hormone like substance that can damage heart valves, most commonly the tricuspid valve and pulmonary valves. The valve leaflets adhere to the right ventricular wall owing to the fibrous plaques on the valve leaflets and the endocardium. Thus, the tricuspid cusps do not coapt appropriately during systole causing tricuspid regurgitation.[10]

- Connective tissue disorders (e.g. Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis). Marfan syndrome, a genetic disorder of connective tissue present at birth, is occasionally associated with tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Radiation therapy. Chest radiation may damage the tricuspid valve and cause tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Past use of a diet pill called “Fen-Phen” (phentermine and fenfluramine) or dexfenfluramine. The drug was removed from the market in 1997.

- The dopamine agonist pergolide may induce tricuspid regurgitation 9.

Disorders leading to functional (secondary) tricuspid regurgitation include 6:

- Causes of left-sided heart failure (especially from mitral stenosis or mitral regurgitation)

- pulmonary hypertension

- right ventricular myocardial infarction

- left-to-right shunts

- Eisenmenger syndrome

- pulmonary stenosis

- pulmonary regurgitation

- hyperthyroidism

Risk factors for developing tricuspid valve regurgitation

Several factors can increase your risk of tricuspid valve regurgitation, including:

- Infections such as infective endocarditis or rheumatic fever. These infections can cause damage to the tricuspid valve.

- A heart attack. A heart attack can damage your heart and affect the right ventricle and function of the tricuspid valve.

- Heart failure. Heart failure can increase your risk of developing tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Pulmonary hypertension. High blood pressure in the arteries in your lungs (pulmonary hypertension) can increase your risk of tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Heart disease. Several forms of heart disease and heart valve disease may increase your risk of developing tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Congenital heart disease. You may be born with a condition or heart defect that affects your tricuspid valve, such as Ebstein’s anomaly.

- Use of certain medications. If you’ve used stimulant medications such as fenfluramine (no longer sold on the market) or some medications for Parkinson’s disease, such as pergolide (no longer sold in the United States) or cabergoline, or certain migraine medications (ergot alkaloids), you may have an increased risk of tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Radiation. Chest radiation may damage the tricuspid valve and cause tricuspid valve regurgitation.

Tricuspid regurgitation prevention

People with abnormal or damaged heart valves are at risk for an infection called endocarditis. Anything that causes bacteria to get into your bloodstream may lead to this infection. Steps to avoid this problem include:

- Avoid unclean injections.

- Treat strep infections promptly to prevent rheumatic fever.

- Always tell your health care provider and dentist if you have a history of heart valve disease or congenital heart disease before treatment. Some people may need to take antibiotics before having a procedure.

Prompt treatment of disorders that can cause valve or other heart diseases reduces your risk of tricuspid regurgitation.

Tricuspid regurgitation symptoms

Mild tricuspid regurgitation may not cause any symptoms. Tricuspid valve regurgitation often doesn’t cause signs or symptoms until the condition is severe. You may be diagnosed with this condition when having tests for other conditions.

Symptoms of heart failure may occur, and can include:

- Active pulsing in the neck veins

- Decreased urine output

- Fatigue, tiredness

- General swelling

- Enlarged liver

- Swelling of the abdomen

- Swelling of the feet and ankles

- Weakness

- Declining exercise capacity

- Abnormal heart rhythms

- Shortness of breath with activity

You may also notice signs or symptoms of the underlying condition that’s causing tricuspid valve regurgitation, such as pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary hypertension symptoms may include fatigue, weakness, difficulty exercising and shortness of breath.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation complications

If tricuspid valve regurgitation lasts, it can lead to:

- Heart failure. In severe tricuspid valve regurgitation, pressure can rise in your right ventricle due to blood flowing backward into the right atrium and less blood flowing forward through the right ventricle and into the lungs. Your right ventricle can expand and weaken over time, leading to heart failure.

- Atrial fibrillation. Some people with severe tricuspid valve regurgitation also may have a common heart rhythm disorder called atrial fibrillation.

Tricuspid regurgitation diagnosis

Your health care provider may find abnormalities when gently pressing with the hand (palpating) on your chest. Your doctor may also feel a pulse over your liver. The physical exam may show liver and spleen swelling.

Listening to the heart with a stethoscope may reveal a murmur or other abnormal sounds. There may be signs of fluid buildup in the abdomen.

An ECG or echocardiogram may show enlargement of the right side of the heart. Doppler echocardiography or right-sided cardiac catheterization may be used to measure blood pressure inside the heart and lungs.

Other tests, such as CT scan or MRI of the chest (heart), may reveal enlargement of the right side of the heart and other changes.

Echocardiogram

This is the main test used to diagnose tricuspid valve regurgitation. In this test, sound waves produce detailed images of your heart. This test assesses the structure of your heart, the tricuspid valve and the blood flow through your heart. Your doctor also may order a 3-D echocardiogram.

Your doctor may also order a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). In this test, a doctor inserts a tube with a tiny sound device (transducer) into the part of your digestive tract that runs from your throat to your stomach (esophagus). Because the esophagus lies close to your heart, the transducer provides a detailed image of your heart.

Cardiac MRI

A cardiac MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of your heart. This test may be used to determine the severity of your condition and assess the size and function of your lower right heart chamber (right ventricle).

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

In this test, sensor patches with wires attached (electrodes) measure the electrical impulses given off by your heart. An ECG can detect enlarged chambers of your heart, heart disease and abnormal heart rhythms.

Chest X-ray

In a chest X-ray, your doctor studies the size and shape of your heart and evaluates your lungs.

Exercise tests or stress tests

Different exercise tests help measure your activity tolerance and monitor your heart’s response to physical exertion. If you are unable to exercise, medications to mimic the effect of exercise on your heart may be used.

Cardiac catheterization

Doctors rarely use this test to diagnose tricuspid valve regurgitation. However, in some cases doctors may order it to determine certain causes of tricuspid valve regurgitation and to help decide on treatment.

In this procedure, doctors insert a long, thin tube (catheter) into a blood vessel in your groin, arm or neck and guide it to your heart using X-ray imaging. A special dye injected through the catheter helps your doctor see the blood flow through your heart, blood vessels and valves, and allows your doctor to check for abnormalities inside the heart and lungs. The pressure in the heart chambers and blood vessels can also be checked during this procedure.

Tricuspid regurgitation treatment

Treatment may not be needed if there are few or no symptoms. You may need to go to the hospital to diagnose and treat severe symptoms.

Swelling and other symptoms of heart failure may be managed with medicines that help remove fluids from the body (diuretics).

Some people may be able to have surgery to repair or replace the tricuspid valve. Surgery is most often done as part of another procedure.

Treatment of certain conditions may correct this disorder. These include:

- High blood pressure in the lungs (pulmonary hypertension)

- Swelling of the right lower heart chamber

Regular monitoring

If you have mild tricuspid valve regurgitation, you may only need to have regular follow-up appointments with your doctor to monitor your condition.

Medications

In patients with tricuspid regurgitation secondary to left-sided heart failure, adequate control of fluid overload is indicated. Diuretics are suggested in these cases. Loop diuretics are commonly used. Restricted intake of salt is indicated. The head of the bed should be elevated as it may improve dyspnea. Digitalis, potassium-sparing diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and anticoagulants are indicated in these patients. Atrial fibrillation, if present, can be controlled by starting the patients on antiarrhythmics.

The following medications are used:

- Diuretics: Furosemide

- Antiarrhythmics

- Digoxin

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- Anticoagulants

Surgery

Your doctor may recommend surgery to repair or replace the tricuspid valve if you have severe tricuspid valve regurgitation and you’re experiencing signs or symptoms, or if your heart begins to enlarge and heart function begins to decrease. In some cases, your doctor may recommend surgery for severe tricuspid valve regurgitation even if you don’t have symptoms but your heart is enlarging. Your doctor will evaluate you and determine if you’re a candidate for heart valve repair or replacement.

If you have tricuspid valve regurgitation and you’re having heart surgery to treat other heart conditions, such as mitral valve surgery, your doctor may recommend that you have tricuspid valve surgery at the same time.

Tricuspid Valve Surgery

Indications for tricuspid valve surgery depend upon whether surgery for left-sided (aortic or mitral) valve disease is indicated

For patients undergoing left-sided valve surgery:

- Tricuspid valve surgery is recommended in these patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation, as observed in the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology and the 2012 European Society of Cardiology valvular disease guidelines 10, 11, 12

- Patients undergoing left-sided valve surgery and who have mild, moderate or severe tricuspid regurgitation, concomitant tricuspid valve repair is recommended in the following cases:

- Dilation of the tricuspid annulus (transthoracic echocardiogram indicating a diameter of greater than 40 mm or 21 mm/m2 indexed for body surface area or intraoperative diameter greater than 70 mm)

- Previous history of right heart failure. This is a recommendation in the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology valve guidelines 13 and similar recommendations are indicated in the 2012 European Society of Cardiology guidelines 14

Isolated Tricuspid Surgery

The appropriate timing of isolated tricuspid valve surgery is not well established.

In patients who are refractory to medical treatment but have severe tricuspid regurgitation, tricuspid valve surgery is suggested (weak recommendation). It is preferred to perform it before the onset of significant right ventricular dysfunction to control or prevent symptoms, as recommended in the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology valvular guidelines 13.

In symptomatic and severe isolated tricuspid regurgitation without right ventricular dysfunction, tricuspid valve surgery is strongly recommended as per the 2012 European Society of Cardiology valvular guidelines 14.

In asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation, the role of tricuspid valve surgery is ambiguous. The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology valvular guidelines note this uncertainty and include a very weak recommendation that tricuspid valve surgery may be considered for asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with severe primary tricuspid regurgitation and progressive moderate or greater RV dilation and/or systolic dysfunction 13. The European Society of Cardiology guidelines view surgery in this setting slightly more favorably and indicate that surgery should be considered in patients with severe isolated tricuspid regurgitation with mild or no symptoms and progressive right ventricular dilation or deterioration of right ventricular function 14.

Treatment Based on the causes

In tricuspid valve endocarditis, it is recommended to excise the tricuspid valve without immediate replacement. The excision of the diseased valve wipes out the endocarditis while the antibiotic treatment is continued. An artificial valve can be inserted if the right heart failure symptoms are refractory to medical management and the infection is well controlled.

In Ebstein anomaly, no surgery is needed in asymptomatic tricuspid regurgitation. However, symptomatic patients may need to be treated with the tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

Surgical options

Heart valve repair

Surgeons try to repair the heart valve instead of replacing it whenever possible. Your surgeon may perform valve repair by separating tethered valve leaflets, closing holes in leaflets, or reshaping the valve leaflets so that they can make contact with each other and prevent backward flow. Surgeons may often tighten or reinforce the ring around a valve (annulus) by implanting an artificial ring.

Some surgeons perform cone repair, a newer form of tricuspid valve repair, to repair tricuspid valves in people with Ebstein’s anomaly. In the cone reconstruction, surgeons separate the leaflets of the tricuspid valve from the underlying heart muscle. The leaflets are then rotated and reattached, creating a “leaflet cone.”

The cone procedure

In the cone procedure for tricuspid valve repair, the surgeon isolates the deformed leaflets of the tricuspid valve and reshapes them so that they function properly.

Repair leaves you with your own functioning tissue, which is resistant to infection and doesn’t require blood-thinning medication, and optimizes function of the right ventricle.

Heart valve replacement

If your tricuspid valve can’t be repaired, your surgeon may perform tricuspid valve replacement. In tricuspid valve replacement, your surgeon removes the damaged valve and replaces it with a mechanical valve or a valve made from cow, pig or human heart tissue (biological tissue valve).

Biological tissue valves degenerate over time, and often eventually need to be replaced.

Mechanical valves are used less often to replace tricuspid valves than to replace mitral or aortic valves. If you have a mechanical valve, you’ll need to take blood-thinning medications for life to prevent blood clots. Your doctor can discuss the risks and benefits of each type of heart valve with you and discuss which valve may be appropriate for you.

Catheter procedure

In some cases, if your biological tissue valve replacement is no longer working, doctors may conduct a catheter procedure to replace the valve. In this procedure, doctors insert a catheter with a balloon at the end into a blood vessel in your neck or leg and thread it to the heart using imaging. A replacement valve is inserted through the catheter and guided to the heart.

Doctors then inflate the balloon in the biological tissue valve in the heart, and place the replacement valve inside the valve that is no longer working properly. The new valve is then expanded.

Maze procedure

If you have fast heart rhythms, your surgeon may perform the maze procedure during valve repair or replacement to correct the fast heart rhythms. In this procedure, a surgeon makes small incisions in the upper chambers of your heart to create a pattern or maze of scar tissue.

Because scar tissue doesn’t conduct electricity, it interferes with stray electrical impulses that cause some types of fast heart rhythms. Extreme cold (cryotherapy) or radiofrequency energy also may be used to create the scars.

Catheter ablation

If you have fast or abnormal heart rhythms, your doctor may perform catheter ablation. In this procedure, your doctor threads one or more catheters through your blood vessels to your heart. Electrodes at the catheter tips can use heat, extreme cold or radiofrequency energy to damage (ablate) a small spot of heart tissue and create an electrical block along the pathway that’s causing your arrhythmia.

Surgery complications

Complications of operative interventions include:

- Heart block

- Thrombosis of the prosthetic valve

- Infection

- Arrhythmias

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Further inpatient care of a patient with tricuspid regurgitation involves:

- Anticoagulation may be needed in cases of atrial fibrillation or if the patient has sustained a valve replacement.

- Management of arrhythmias, if present

- Treatment of any infections

- Heart failure

In patients whose valve has been removed, repeat echocardiography is indicated at 6-month intervals. In patients whose valve has been replaced, annual echocardiography is recommended.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Your doctor may recommend that you make some lifestyle changes to improve your heart health and to live with tricuspid valve regurgitation, including:

- Eat a heart-healthy diet. Eat a variety of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins. Avoid saturated fats and trans fats, sugar, salt, and refined grains.

- Exercise. Exercise can help improve your heart health. However, check with your doctor before you begin an exercise plan, especially if you’re interested in participating in competitive sports. The amount and type of exercise your doctor recommends for you may depend on your condition, if you have other heart valve conditions and if your condition is caused by other conditions.

- Prevent infective endocarditis. If you have had a heart valve replaced, your doctor may recommend you take antibiotics before dental procedures to prevent an infection called infective endocarditis. Check with your doctor to find out if he or she recommends that you take antibiotics before dental procedures.

- Prepare for pregnancy. If you have tricuspid valve regurgitation and you’re thinking about becoming pregnant, talk with your doctor first. If you have severe tricuspid valve regurgitation, you’ll need to be monitored by a cardiologist and medical team experienced in treating women with heart valve conditions during pregnancy. If your condition is due to a congenital heart condition, such as Ebstein’s anomaly, you may need to be evaluated by a doctor trained in congenital heart disease. Discuss the risks with your doctor.

- See your doctor regularly. Establish a regular evaluation schedule with your cardiologist or primary care provider. Let your doctor know if you have any changes in your signs or symptoms.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation prognosis

Prognosis of tricuspid regurgitation is generally good 1. The outlook is poor for people who have symptomatic, severe tricuspid regurgitation that cannot be corrected.

References- Mulla S, Siddiqui WJ. Tricuspid Regurgitation (Tricuspid Insufficiency) [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526121

- Badano LP, Muraru D, Enriquez-Sarano M. Assessment of functional tricuspid regurgitation. (2013) European Heart Journal. 34 (25): 1875. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs474

- McNaughton DA, Abu-Yousef MM. Doppler US of the liver made simple. (2011) Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 31 (1): 161-88. doi:10.1148/rg.311105093

- Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 16 (7): 777-802. doi:10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00335-3

- Ton-Nu TT, Levine RA, Handschumacher MD, Dorer DJ, Yosefy C, Fan D, Hua L, Jiang L, Hung J. Geometric determinants of functional tricuspid regurgitation: insights from 3-dimensional echocardiography. (2006) Circulation. 114 (2): 143-9. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.611889

- Rogers JH, Bolling SF. The Tricuspid Valve. (2009) Circulation. 119 (20): 2718. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842773

- Fauci AS. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division; 2008.

- Surapaneni P, Vinales KL, Najib MQ et-al. Valvular heart disease with the use of fenfluramine-phentermine. Tex Heart Inst J. 2012;38 (5): 581-3.

- Baseman DG, O’Suilleabhain PE, Reimold SC, Laskar SR, Baseman JG, Dewey RB. Pergolide use in Parkinson disease is associated with cardiac valve regurgitation. Neurology. 2004 Jul 27;63(2):301-4.

- Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Lansac E, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Rosenhek R, Sjögren J, Tornos Mas P, Vahanian A, Walther T, Wendler O, Windecker S, Zamorano JL., ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2017 Sep 21;38(36):2739-2791.

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Fleisher LA, Jneid H, Mack MJ, McLeod CJ, O’Gara PT, Rigolin VH, Sundt TM, Thompson A. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017 Jun 20;135(25):e1159-e1195.

- Antunes MJ, Rodríguez-Palomares J, Prendergast B, De Bonis M, Rosenhek R, Al-Attar N, Barili F, Casselman F, Folliguet T, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Muneretto C, Obadia JF, Pierard L, Suwalski P, Zamorano P., ESC Working Groups of Cardiovascular Surgery and Valvular Heart Disease. Management of tricuspid valve regurgitation: Position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Groups of Cardiovascular Surgery and Valvular Heart Disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017 Dec 01;52(6):1022-1030.

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Guyton RA, O’Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM, Thomas JD., American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 Jun 10;63(22):e57-185.

- Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, Antunes MJ, Barón-Esquivias G, Baumgartner H, Borger MA, Carrel TP, De Bonis M, Evangelista A, Falk V, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Pierard L, Price S, Schäfers HJ, Schuler G, Stepinska J, Swedberg K, Takkenberg J, Von Oppell UO, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Zembala M. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur. Heart J. 2012 Oct;33(19):2451-96.