What is typhlitis

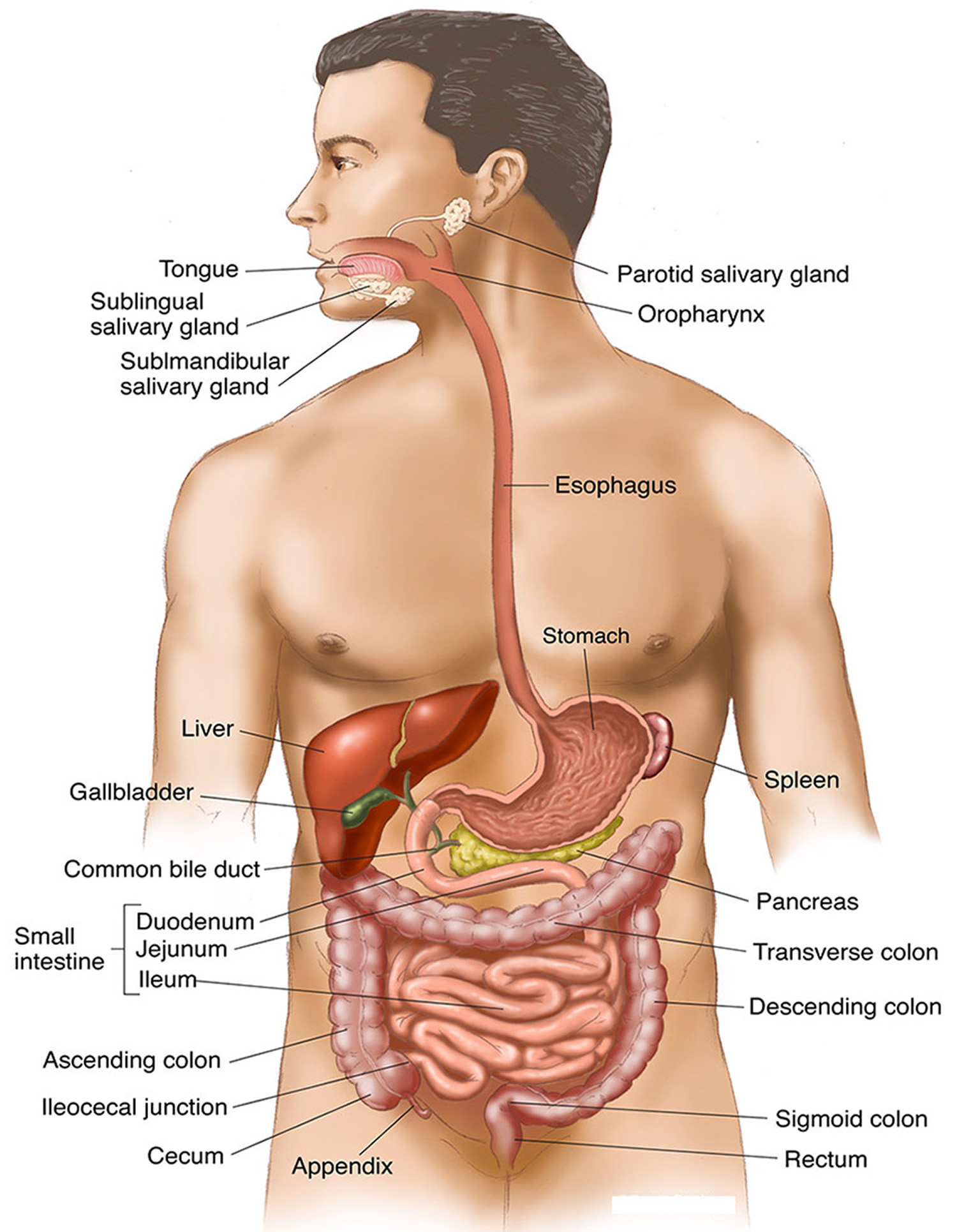

Typhlitis is also referred to as neutropenic colitis 1, necrotizing colitis 2, ileocecal syndrome, or cecitis 3, is a necrotizing inflammatory condition which typically involves the cecum and sometimes, can extend into the ascending colon or terminal ileum. Typhlitis commonly occurs in neutropenic patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment for a hematologic malignancy, most frequently patients with acute myelogenous leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia 4. However, typhlitis has also been reported in patients with aplastic anemia, lymphoma, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and after kidney transplantation 5.

Typhlitis appears to be more common among children than among adults 6. Typhlitis may also complicate the treatment of patients with solid tumors 7 and granulocytopenia from other causes 8. Although the cecum is most commonly affected, other potential areas of involvement include the ileum and ascending colon 6. According to some experts, patients with typhlitis have been granulocytopenic for 1 or more weeks before the onset of symptoms. Typhlitis is a consequence of overgrowth of clostridia, particularly Clostridium septicum, in granulocytopenic patients 9. The process appears to begin with mucosal disruption, leading to secondary intramural infection and subsequent edema, induration, and wall thickening 10. Chemotherapeutic agents may themselves alter mucosal integrity 11. To date, a predictor of typhlitis has not been identified, in that chemotherapy, neutropenia, fever, and antibiotic use are found with equal frequency in patients with and without typhlitis 12.

Typhlitis refers to a clinical syndrome of fever, watery or bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain, which may be localized to the right lower quadrant tenderness in a neutropenic patient after cytotoxic chemotherapy 12. Typhlitis is characterized by edema and inflammation of the cecum, the ascending colon, and sometimes the terminal ileum. The inflammation can be so severe that transmural necrosis, perforation, and death can result 13. The mechanism of neutropenic typhlitis is not known, but it is probably due to a combination of ischemia, infection (especially with cytomegalovirus), mucosal hemorrhage, and perhaps neoplastic infiltration 5. Treatment consists of bowel rest, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), antibiotics, and aggressive fluid and electrolyte replacement. Resolution usually corresponds with adequate return of functioning neutrophils. Surgery is indicated in patients with uncontrollable gastrointestinal bleeding, obstruction, abscess, transmural necrosis, free intramural perforation, or uncontrolled sepsis. At surgery, all necrotic bowel tissue must be resected 14.

Typhlitis causes

The exact cause of typhlitis is unknown but is believed due to a combination of ischemia, infection (especially with cytomegalovirus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa), mucosal hemorrhage, and perhaps neoplastic infiltration 15.

Typhlitis is characterized by intramural bacterial invasion without an inflammatory reaction. This then leads to edematous thickening and induration of the cecal wall or other mural segments of the colon and distal small bowel.

Typhlitis was first described in children with leukemia and severe neutropenia (seen with an absolute neutrophil count < 1000 per microliter). Typhlitis most commonly occurs in immunocompromised patients, chemotherapy and steroid therapy patients including:

- leukemia (most common)

- lymphoma

- aplastic anemia

- AIDS

- solid organ transplant

Although cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents account for most cases of neutropenic enterocolitis, other conditions may also predispose some patients to develop this condition.

The cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents include cytosine arabinoside, vinca alkaloids, and doxorubicin. Other drugs that have been implicated anecdotally include paclitaxel, docetaxel, procainamide, sulfasalazine, 5-fluorouracil, vinorelbine, carboplatin, cisplatin, gemcitabine, leucovorin, and pemetrexed 16.

There have been described cases of neutropenic enterocolitis associated with the monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab 17, as well as with pegylated interferon (PEG-INF) in combination with ribavirin 18.

Other predisposing conditions for neutropenic enterocolitis include the following:

- Myelodysplastic syndromes, multiple myeloma, and aplastic anemia

- Solid organ and bone marrow transplantation

- Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

- Cyclic neutropenia

- Solid malignant tumors

- Lymphomas

Typhlitis symptoms

Most patients who are affected with neutropenic typhlitis are receiving antineoplastic drugs and are profoundly neutropenic (ie, < 1000 cells/μL). The time course and severity of the clinical presentation of neutropenic typhlitis is variable. Symptoms usually occur within 10-14 days after the initiation of cytotoxic chemotherapy. The typical presentation mimics that of acute appendicitis. Clinically, patients with typhlitis present with a mixture of localized and systemic symptoms including a fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, tenderness and a distended abdomen. Peritoneal irritation and occult bloody stools may be present. Pain in the right lower quadrant may mimic appendicitis.

Typhlitis symptoms include the following:

- Right-lower-quadrant abdominal pain, which may be cramping and intermittent or a continuous dull ache

- Fever

- Watery or bloody diarrhea, which occurs in about 25-45% of patients 19

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal distention

Oral and pharyngeal mucositis may manifest before the onset of colonic symptoms.

Typhlitis complications

Complications of neutropenic enterocolitis include the following:

- Bowel perforation and peritonitis

- Gastrointestinal bleeding 20

- Gastrointestinal obstruction

- Intra-abdominal abscess

- Sepsis

- Death

Typhlitis diagnosis

Typhlitis should be suspected when a neutropenic patient presents with fever and abdominal pain, particularly in the right lower quadrant, with or without rebound tenderness. Associated diarrhea, often bloody, is common. Abdominal distention and nausea and vomiting are also common symptoms 21. Given that the clinical presentation can be subtle and there are no pathognomonic clinical findings, one must consider other entities in the differential diagnosis, such as pseudomembranous colitis, colonic pseudoobstruction, acute appendicitis, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and infectious colitis. Imaging studies can be useful in supporting a diagnosis of typhlitis. Computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography can demonstrate bowel wall thickening and exclude other intraabdominal processes. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are more sensitive for diagnosis than are other imaging modalities, and they are noninvasive 22. Plain radiography is nonspecific, but may show any of these features: a relative paucity of bowel gas in the right lower quadrant, with a slight distention of surrounding small bowel; a soft-tissue density secondary to an atonic, fluid-filled right colon that may be dilated and may exhibit thumbprinting of the mucosa; or small bowel obstruction 23. Findings at colonoscopy include mucosal erythema, edema, friability, and ulcerations. In some cases, a nodular tumorlike mass is seen 24. Colonoscopy should be done cautiously to minimize the risk of perforation. Alternatively, flexible sigmoidoscopy can be performed to exclude pseudomembranous colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and infectious colitis. Barium enema, if it is to be performed, should also be done with caution, and findings include cecal distortion with edema and effacement of the mucosa, rigidity, loss of haustral markings, and thumbprinting 3. On pathologic examination, the bowel is dilated and edematous, and the mucosa is frequently hemorrhagic and may contain multiple ulcerations 25. Transmural involvement may be present, and there is usually a sparse inflammatory infiltrate, edema (so-called phlegmonous colitis), intramural hemorrhage, necrosis, and evidence of either bacterial or fungal infection. Leukemic infiltration is not routinely found 26.

Physical Examination

Physical findings in patients with neutropenic enterocolitis vary according to the severity of the disease and the presence or absence of complications. The following may be noted:

- Abdominal distention, hypoactive bowel sounds, and a tympanitic abdomen may suggest ileus

- The abdomen may be markedly tender, especially in the right lower quadrant

- The cecum may be palpated as a boggy mass

- Rebound tenderness and rigidity may suggest colonic perforation

- Shock may be present as a consequence of sepsis

Laboratory Studies

A complete blood cell (CBC) count is used to confirm neutropenia. A serum bicarbonate level and pH value should be obtained to rule out acidosis.

Obtain stool studies for the following:

- Clostridium difficile toxin to rule out pseudomembranous colitis

- Culture for enteric pathogens to rule out infectious causes of enterocolitis

Obtain blood cultures for aerobic/anaerobic bacteria and fungus to rule out bacterial and fungal sepsis.

Typhlitis radiology

Plain abdominal radiographs rarely help in the diagnosis of neutropenic enterocolitis. Radiographic findings usually are nonspecific and may even be normal. Nonspecific findings may include the following:

- Right-side colonic and small-bowel dilatation

- Thumbprinting (see the image below) of the right colon

- Paucity of air in the right colon because of a fluid-filled colon

- Intramural air or pneumatosis

- Soft-tissue mass displacing the small bowel

Barium enema is usually contraindicated, especially if a potential for perforation exists. Water-soluble contrast may demonstrate rigidity and thickening of the cecum.

Abdominal ultrasonography

Abdominal ultrasonography is one of the most important diagnostic studies for neutropenic enterocolitis, and it is preferable to contrast enemas. Ultrasonography may be also useful as a follow-up tool to assess the gradual decrease in bowel-wall thickening.

Findings include thickening of the bowel wall that produces a target or halo sign. However, this is a nonspecific finding and may be observed in other conditions listed under the differential diagnosis.

Bowel-wall thickness has also been suggested as a significant prognostic factor regarding patient outcome in individuals with neutropenic enterocolitis 27. A retrospective study using ultrasonography showed that mortality was higher in patients with a bowel-wall thickness greater than 5 mm (29%) than in those without bowel-wall thickening (0%) 28. If the bowel-wall thickness cutoff was set at greater than 10 mm, the mortality was 60%, as compared with 4.2% in those without bowel-wall thickening.

Bowel-wall thickening has also been associated with the duration of illness and neutropenia in neutropenic enterocolitis 29.

Ultrasonography also allows follow-up imaging without repeated exposure to ionizing radiation, an especially important consideration in children and younger adults 30.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning

CT scanning of the abdomen (see the images below) is the diagnostic procedure of choice in neutropenic enterocolitis 30, because it has a lower false-negative rate (15%) than ultrasonography (23%) or plain abdominal radiography (48%). CT scanning is also the test of choice for diagnosing alternative causes of abdominal pain, such as megacolon, appendicitis, and small-bowel obstruction 31.

CT scan findings include the following:

- Symmetrical thickening of the cecum

- Fluid-filled cecum

- Pericecal inflammation

- Free air if an underlying perforation exists

- Portal venous gas

Endoscopic procedures that may be considered in the setting of neutropenic enterocolitis include colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy. However, these procedures are relatively contraindicated in patients with neutropenic enterocolitis because of an increased risk of complications (eg, perforation) 30, especially in the context of underlying neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. They are usually unnecessary, except in rare circumstances in which a gentle sigmoidoscopy may aid in the diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis.

Typhlitis treatment

Patients with typhlitis are often very ill and have an increased mortality rate 32. The treatment is conservative medical management while awaiting recovery of granulocytes. Patients with neutropenic typhlitis must be monitored in an intensive care unit (ICU) with serial abdominal examinations. Management of these patients often is not straightforward. A wide range of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches have been proposed for neutropenic typhlitis. At diagnosis, patients should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics with anaerobic coverage 33. In some cases, patients were found to have positive blood cultures for aerobic gram-negative bacilli. Marrow-stimulating growth factors may be considered. Use of recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) may be considered in individual patients, depending on the clinical progression 34. Controlled trials using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) in this specific entity are lacking, although several case reports of a successful outcome have been reported in the literature. Moreover, a better understanding and definition of specific subsets of patients that may benefit from treatment or prevention of neutropenic enterocolitis is needed.

There are anecdotal reports of successful treatment with oral vancomycin; antiperistaltic agents should be avoided 35. Recurrence is rare, and most patients recover uneventfully. Surgical therapy has been successful in rare patients who fail medical treatment 36. Proposed criteria for surgical intervention include (1) persistent gastrointestinal bleeding after resolution of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia and correction of clotting abnormalities; (2) evidence of free intraperitoneal perforation; (3) clinical deterioration requiring support with vasopressors or large volumes of fluid, suggesting uncontrolled sepsis; and (4) development of symptoms of an intraabdominal process, which, in the absence of neutropenia, would normally require surgery 37. A review of the published literature suggests that surgical versus medical management is associated with better outcomes. However, these results must be cautiously interpreted, as the two patient groups are not comparable 12. It is likely that medically untreated patients had greater severity of illness and may have been unfit for surgery 37.

Typhlitis prognosis

The prognosis of neutropenic typhlitis is generally poor and is highly dependent on the rapidity of restoration of the white blood cell count. The potential for recovery from neutropenic typhlitis may be improved by early, accurate diagnosis along with aggressive and meticulous medical and supportive therapy 38.

Mortality figures in the range of 5-100% have been reported with conservative management of neutropenic typhlitis; average mortality is about 40-50% 39.

In a collective review of 178 published cases, mortality for neutropenic enterocolitis was reported as 48% with conservative management and 21% with surgical management 40; however, these numbers cannot be compared with each other because of selection bias. No known prospective randomized trials comparing surgery with medical management have been performed.

References- Fekety R , Silva J , Kauffman C . et al. Treatment of antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile colitis with oral vancomycin: comparison of two dosage regimens. Am J Med. 1989;86:15–9

- Alt B , Glass NR , Sollinger H . Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults. Review of the literature and assessment of surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 1985;149:405–8

- Williams N , Scott AD . Neutropenic colitis: a continuing surgical challenge. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1200–5

- Dosik GM , Luna M , Valdivieso M . et al. Necrotizing colitis in patients with cancer. Am J Med. 1979;67:646–56.

- Wall SD, Jones B. Gastrointestinal tract in the immunocompromised host: opportunistic infections and other complications. Radiology 1992; 185:327–335.

- Williams N , Scott AD . Neutropenic colitis: a continuing surgical challenge. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1200–5.

- Shamberger RC , Weinstein HJ , Delorey MJ , Levey RH . The medical and surgical management of typhlitis in children with acute nonlymphocytic (myelogenous) leukemia. Cancer. 1986;57:603–9.

- Keidan RD , Fanning J , Gatenby RA , Weese JL . Recurrent typhlitis. A disease resulting from aggressive chemotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:206–9

- Ryan ME , Morrissey JF . Typhlitis complicating methimazole-induced agranulocytosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:299–302

- Katz JA , Wagner ML , Gresik MV . et al. Typhlitis. An 18-year experience and postmortem review. Cancer. 1990;65:1041–7.

- King A , Rampling A , Wight DG , Warren RE . Neutropenic enterocolitis due to Clostridium septicum infection. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:335–43.

- Sinicrope FA. Typhlitis. In: Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, et al., editors. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th edition. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker; 2003. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK12821

- CT Evaluation of the Colon: Inflammatory Disease. Karen M. Horton, Frank M. Corl, and Elliot K. Fishman. RadioGraphics 2000 20:2, 399-418 https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/pdf/10.1148/radiographics.20.2.g00mc15399

- Moir CR, Scudamore CH, Benny WB. Typhlitis: selective surgical management. Am J Surg 1986; 151:563–566.

- CT evaluation of the colon: inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2000 Mar-Apr;20(2):399-418. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.20.2.g00mc15399

- Tiseo M, Gelsomino F, Bartolotti M, Barili MP, Ardizzoni A. Typhlitis during second-line chemotherapy with pemetrexed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A case report. Lung Cancer. 2009 Aug. 65 (2):251-3

- Marie I, Robaday S, Kerleau JM, Jardin F, Levesque H. Typhlitis as a complication of alemtuzumab therapy. Haematologica. 2007 May. 92 (5):e62-3.

- Kim JH, Jang JW, You CR, You SY, Jung MK, Jung JH. Fatal neutropenic enterocolitis during pegylated interferon and ribavirin combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gut Liver. 2009 Sep. 3 (3):218-21.

- Aksoy DY, Tanriover MD, Uzun O, et al. Diarrhea in neutropenic patients: a prospective cohort study with emphasis on neutropenic enterocolitis. Ann Oncol. 2007 Jan. 18 (1):183-9.

- Park YB, Lee JW, Cho BS, et al. Incidence and etiology of overt gastrointestinal bleeding in adult patients with aplastic anemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Jan. 55 (1):73-81.

- McNamara MJ , Chalmers AG , Morgan M , Smith SE . Typhlitis in acute childhood leukaemia: radiological features. Clin Radiol. 1986;37:83–6.

- Katz JA , Wagner ML , Gresik MV . et al. Typhlitis. An 18-year experience and postmortem review. Cancer. 1990;65:1041–7

- Meyerovitz MF , Fellows KE . Typhlitis: a cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:833–5.

- Gootenberg JE , Abbondanzo SL . Rapid diagnosis of neutropenic enterocolitis (typhlitis) by ultrasonography. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1987;9:222–7

- Matolo NM , Garfinkle SE , Wolfman EF Jr. Intestinal necrosis and perforation in patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs. Am J Surg. 1976;132:753–4

- Frick MP , Maile CW , Crass JR . et al. Computed tomography of neutropenic colitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:763–5

- Rizzatti M, Brandalise SR, de Azevedo AC, Pinheiro VR, Aguiar Sdos S. Neutropenic enterocolitis in children and young adults with cancer: prognostic value of clinical and image findings. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010 Sep. 27 (6):462-70.

- Cartoni C, Dragoni F, Micozzi A, et al. Neutropenic enterocolitis in patients with acute leukemia: prognostic significance of bowel wall thickening detected by ultrasonography. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Feb 1. 19 (3):756-61

- McCarville MB, Adelman CS, Li C, et al. Typhlitis in childhood cancer. Cancer. 2005 Jul 15. 104 (2):380-7.

- [Guideline] Schnell D, Azoulay E, Benoit D, et al. Management of neutropenic patients in the intensive care unit (NEWBORNS EXCLUDED) recommendations from an expert panel from the French Intensive Care Society (SRLF) with the French Group for Pediatric Intensive Care Emergencies (GFRUP), the French Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care (SFAR), the French Society of Hematology (SFH), the French Society for Hospital Hygiene (SF2H), and the French Infectious Diseases Society (SPILF). Ann Intensive Care. 2016 Dec. 6 (1):90.

- Spencer SP, Power N, Reznek RH. Multidetector computed tomography of the acute abdomen in the immunocompromised host: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2009 Jul-Aug. 38 (4):145-55

- McNamara MJ , Chalmers AG , Morgan M , Smith SE . Typhlitis in acute childhood leukaemia: radiological features. Clin Radiol. 1986;37:83–6

- Shamberger RC , Weinstein HJ , Delorey MJ , Levey RH . The medical and surgical management of typhlitis in children with acute nonlymphocytic (myelogenous) leukemia. Cancer. 1986;57:603–9

- Portugal R, Nucci M. Typhlitis (neutropenic enterocolitis) in patients with acute leukemia: a review. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017 Feb. 10 (2):169-74

- Frick MP , Maile CW , Crass JR . et al. Computed tomography of neutropenic colitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:763–5.

- Bradley SJ , Weaver DW , Maxwell NP , Bouwman DL . Surgical management of pseudomembranous colitis. Am Surg. 1988;54:329–32

- Bradley SJ , Weaver DW , Maxwell NP , Bouwman DL . Surgical management of pseudomembranous colitis. Am Surg. 1988;54:329–32.

- Mullassery D, Bader A, Battersby AJ, et al. Diagnosis, incidence, and outcomes of suspected typhlitis in oncology patients–experience in a tertiary pediatric surgical center in the United Kingdom. J Pediatr Surg. 2009 Feb. 44 (2):381-5.

- Neutropenic Enterocolitis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/183791-overview

- Ettinghausen SE. Collagenous colitis, eosinophilic colitis, and neutropenic colitis. Surg Clin North Am. 1993 Oct. 73 (5):993-1016.