Urethral hypermobility

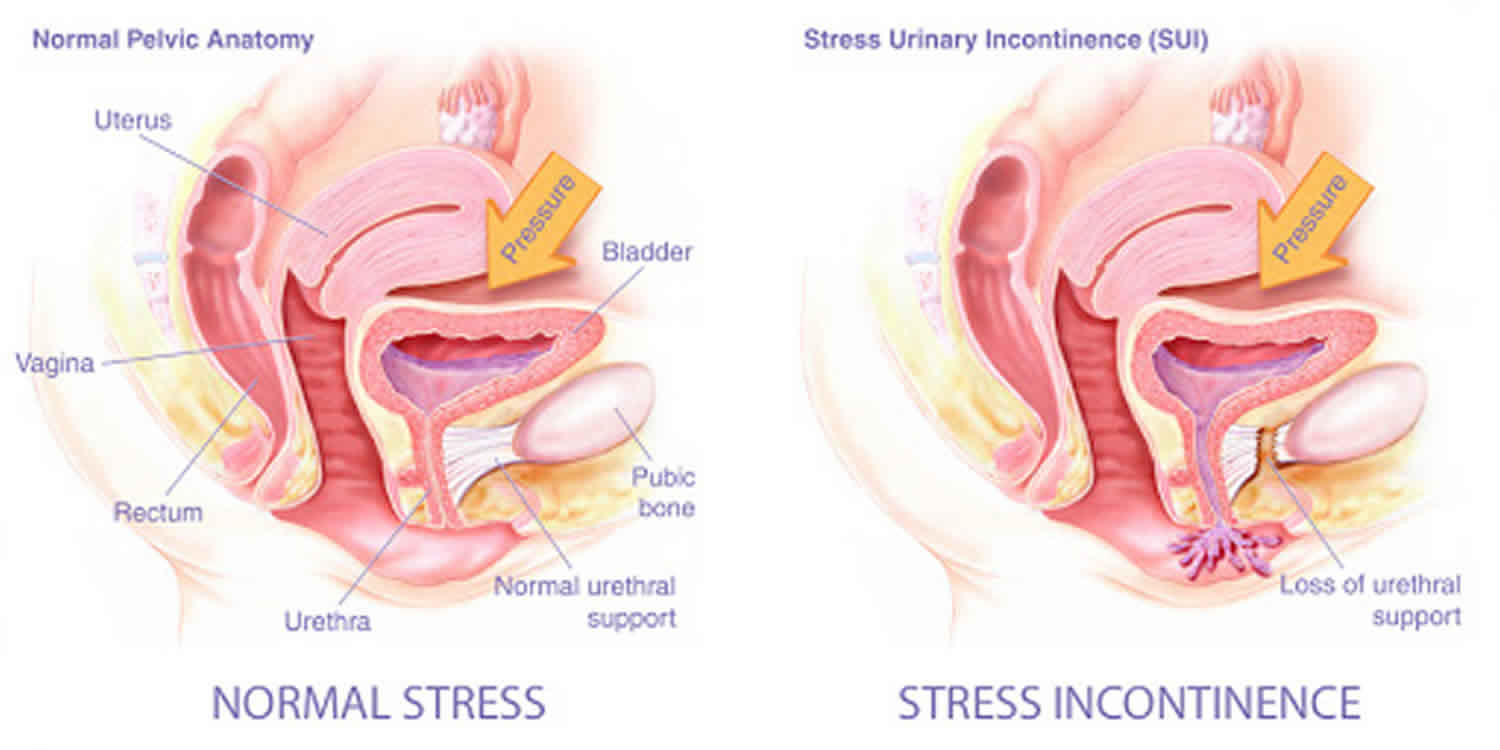

Urethral hypermobility is defined as incompetence of the urethral sphincter mechanisms usually associated with stress incontinence symptoms, due to failure of urethral support. Stress incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine with increased intraabdominal pressure or physical exertion (coughing, sneezing, jumping, lifting, exercise). Urethral hypermobility is related to impaired neuromuscular functioning of the pelvic floor coupled with injury, both remote and ongoing, to the connective tissue supports of the urethra and bladder neck. When this occurs, the proximal urethra and the bladder neck descend to rotate away and out of the pelvis at times of increased intra-abdominal pressure. Because the bladder neck and proximal urethra move out of the pelvis, more pressure is transmitted to the bladder. During this process, the posterior wall of the urethra shears off the anterior urethral wall to open the bladder neck when intrinsic sphincter deficiency is present. Rotation of the urethra during strain over 30° from its resting axis defines urethral hypermobility 1. It often accompanies moderate to severe bladder descent. Urethral hypermobility results from laxity of the suburethral supporting structures, the posterior pubourethral ligament, leading to urethral axis rotation from vertical to horizontal, so-called rotational descent 2.

A related way of describing the mechanism of urethral hypermobility-related stress incontinence is the hammock theory posited by DeLancey 3. Normally, an acute increase in intra-abdominal pressure applies a downward force to the urethra. The urethra is then compressed shut against the firm support provided by the anterior vaginal wall and associated endopelvic connective tissue sheath. If the endopelvic connective tissue is detached from its normal lateral fixation points at the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, optimal urethral compression does not take place. A simple analogy is that of a garden hose (urethra) running over a pavement surface (anterior endopelvic connective tissue). A force is applied in a downward direction using the foot (increased intra-abdominal pressure). This force compresses the hose shut, occluding flow. If the same hose is run through a soft area of mud (damaged connective tissue), then the downward force does not occlude the hose but, rather, pushes the hose deeper into the mud.

An alternative theory of the mechanism of stress incontinence stems from research involving ultrasound visualization of the bladder neck and proximal urethra during stress maneuvers. This research found that 93% of patients with stress incontinence displayed funneling of the proximal urethra with straining, and half of those individuals also showed funneling at rest 4. In addition, during stress maneuvers, the urethra did not rotate and descend as a single unit; rather, the posterior urethral wall moved farther than the anterior wall.

Although mobile, the anterior urethral wall has been observed to stop moving, as if tethered, while the posterior wall continued to rotate and descend. Possibly, the pubourethral ligaments arrest rotational movement of the anterior wall but not the posterior wall. The resulting separation of the anterior and posterior urethral walls might open the proximal urethral lumen, thus allowing or contributing to stress incontinence.

Stress urinary incontinence affects 15.7% of adult women; 77.5% of women report the symptoms to be bothersome and 28.8% report the symptoms to be moderate to severe 5. Prevalence of stress urinary incontinence will increase with age particularly with menopause. One study found that 41% of women older than 40 years old will have urinary incontinence 6. Up to 77% of elderly females in nursing homes will have urinary incontinence 7. In one study, only 60% of women with incontinence sought treatment 6.

One of the most common procedures for urethral hypermobility is a urethroplasty, which is a type of surgery that reconstructs all or some of a damaged urethra. There are different kinds of urethroplasty procedures that can be performed depending on the location, cause, and length of a patient’s urethral stricture. For example, a surgeon may perform a primary anastomotic repair for patients that require the excision of a stricture to widen the urethra’s pathway. In other instances, a substitution repair, which requires buccal mucosa grafts or genital skin flaps, may be necessary to improve or build upon a specific urethral stricture. Women suffering from stress incontinence may benefit from a completely different type of urethral procedure that requires a urethral sling. Ultimately, surgery for a urethral disorder depends on the condition itself.

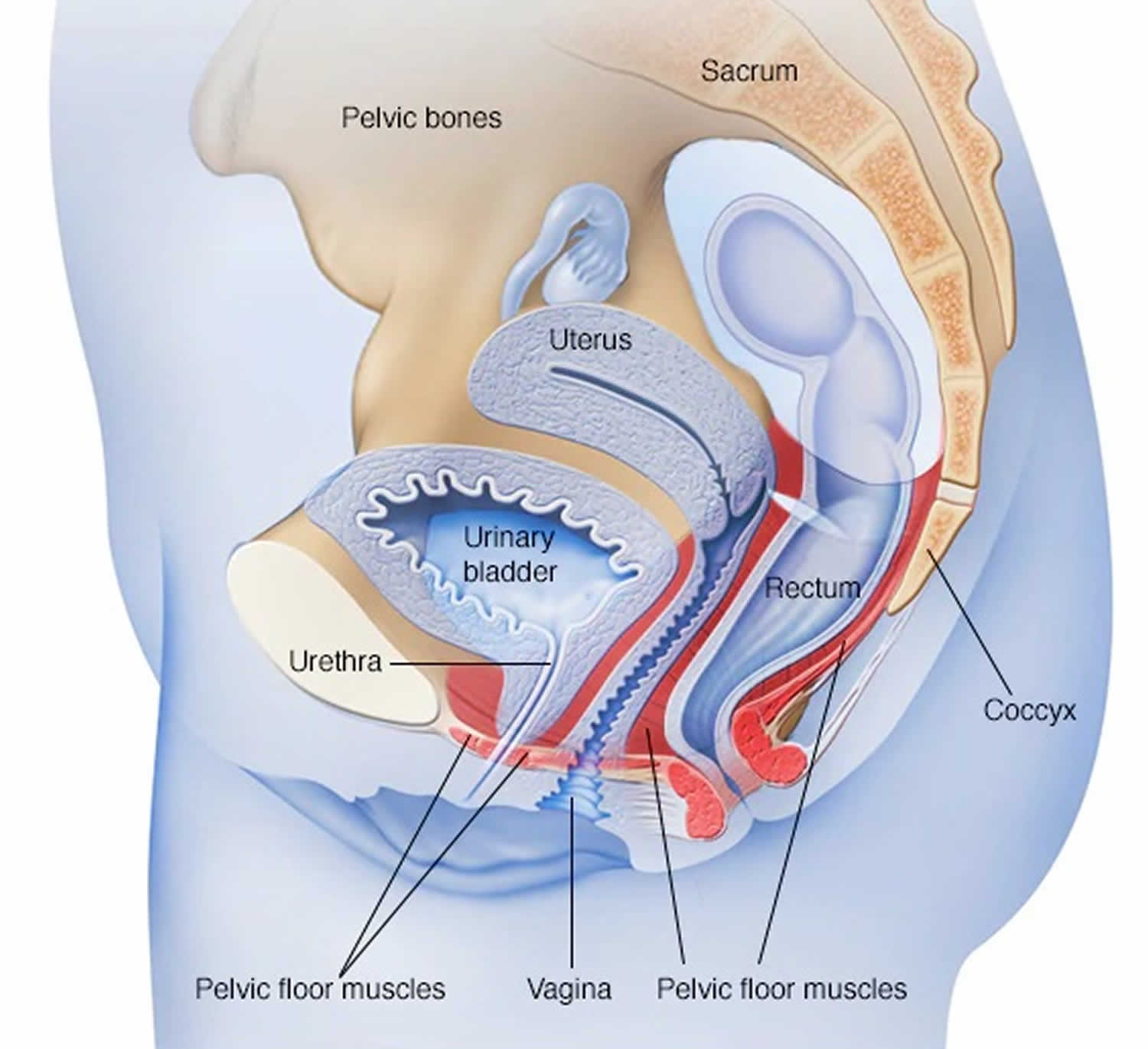

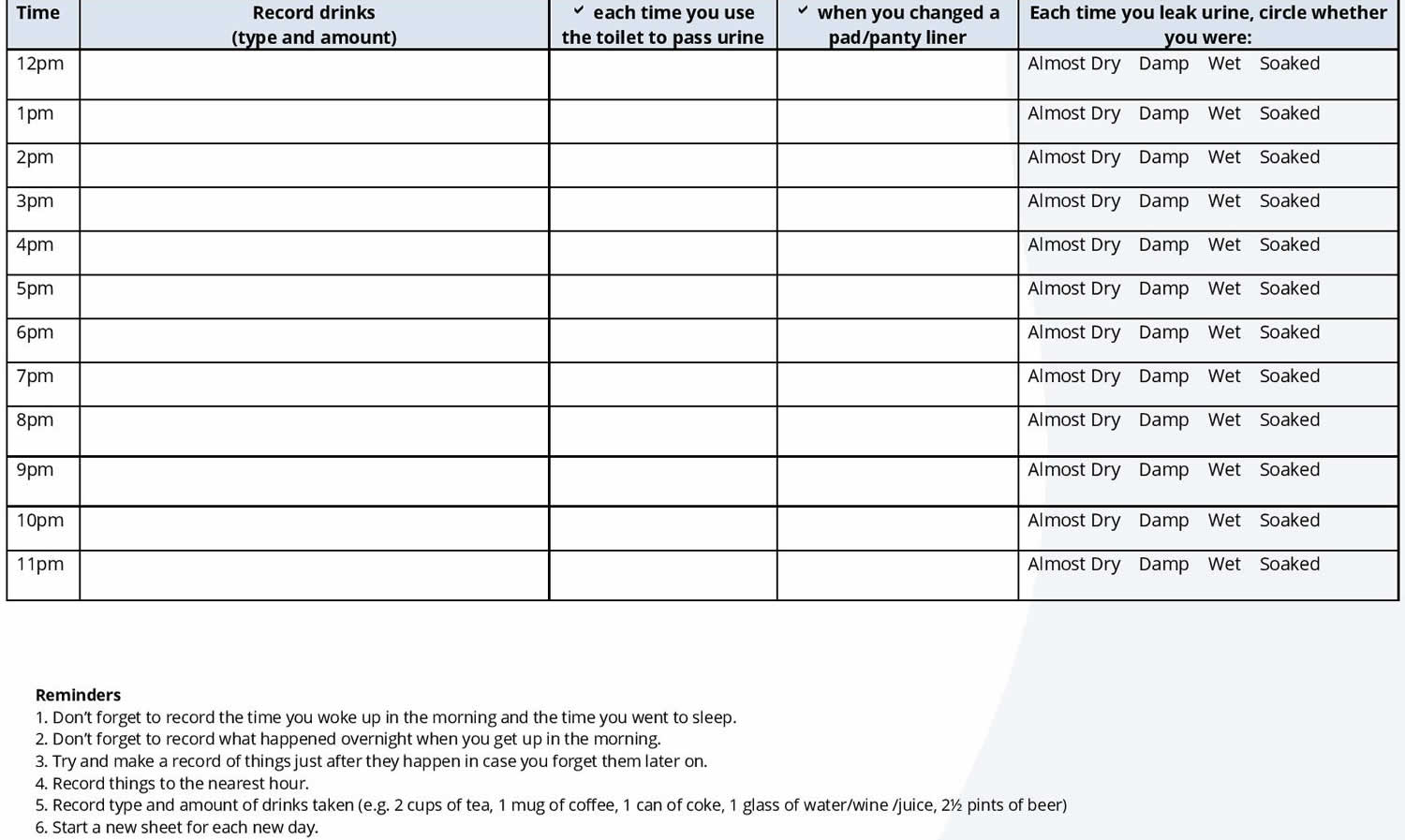

Female pelvic floor anatomy

The bladder has two functions:

- To store urine produced by the kidneys

- To contract and push the urine through the urethra.

The bladder expands as it fills with urine. Controlling the flow of urine out of the bladder is the sphincter muscle. Normally, valve-like muscles in the urethra — the short tube that carries urine out of your body — stay closed as the bladder expands, preventing urine leakage until you reach a bathroom. The nervous system detects when the bladder is ready to be emptied and tells the sphincter to relax, allowing you to urinate. With stress urinary incontinence, physical stresses like exercise, coughing and sneezing put pressure on the top of the bladder. When there is any sort of abdominal stress on the pelvic organs—the bladder, vagina, uterus and rectum—stress urinary incontinence can occur. The urethra is unable to stay closed and urine leaks out.

Your pelvic floor muscles and urinary sphincter may lose strength because of:

- Childbirth. In women, tissue or nerve damage during delivery of a child can weaken the pelvic floor muscles or the sphincter. Stress incontinence from this damage may begin soon after delivery or occur years later.

- Other factors that may worsen stress incontinence include:

- Illnesses that cause chronic coughing

- Obesity

- Smoking, which can cause frequent coughing

- High-impact activities, such as running and jumping, over many years

Figure 1. Female reproductive system

Figure 2. Female pelvic floor muscles (when these muscles weaken, anything that exerts force on the abdominal and pelvic muscles — sneezing, bending over, lifting or laughing hard, for instance — can put pressure on your bladder and cause urine leakage)

Figure 3. Female urinary bladder anatomy

Urethral hypermobility causes

Urethral hypermobility pathophysiology is a lack of support to the upper urethra and bladder outlet due to pelvic floor weakness/prolapse and/or loss of the normal urethra vesical angle.

Stress urinary incontinence occurs when the muscles and other tissues that support the urethra (pelvic floor muscles) and the muscles that control the release of urine (urinary sphincter) weaken.

Causes of stress urinary incontinence are multifactorial and include 8:

- Loss of support from pelvic floor musculature and connective tissue – loss of support can originate from connective tissue disorders, chronic cough, obesity, pelvic floor trauma after vagina delivery, pregnancy, menopause, constipation, heavy lifting, and smoking

- Neuromuscular damage from previous pelvic surgeries

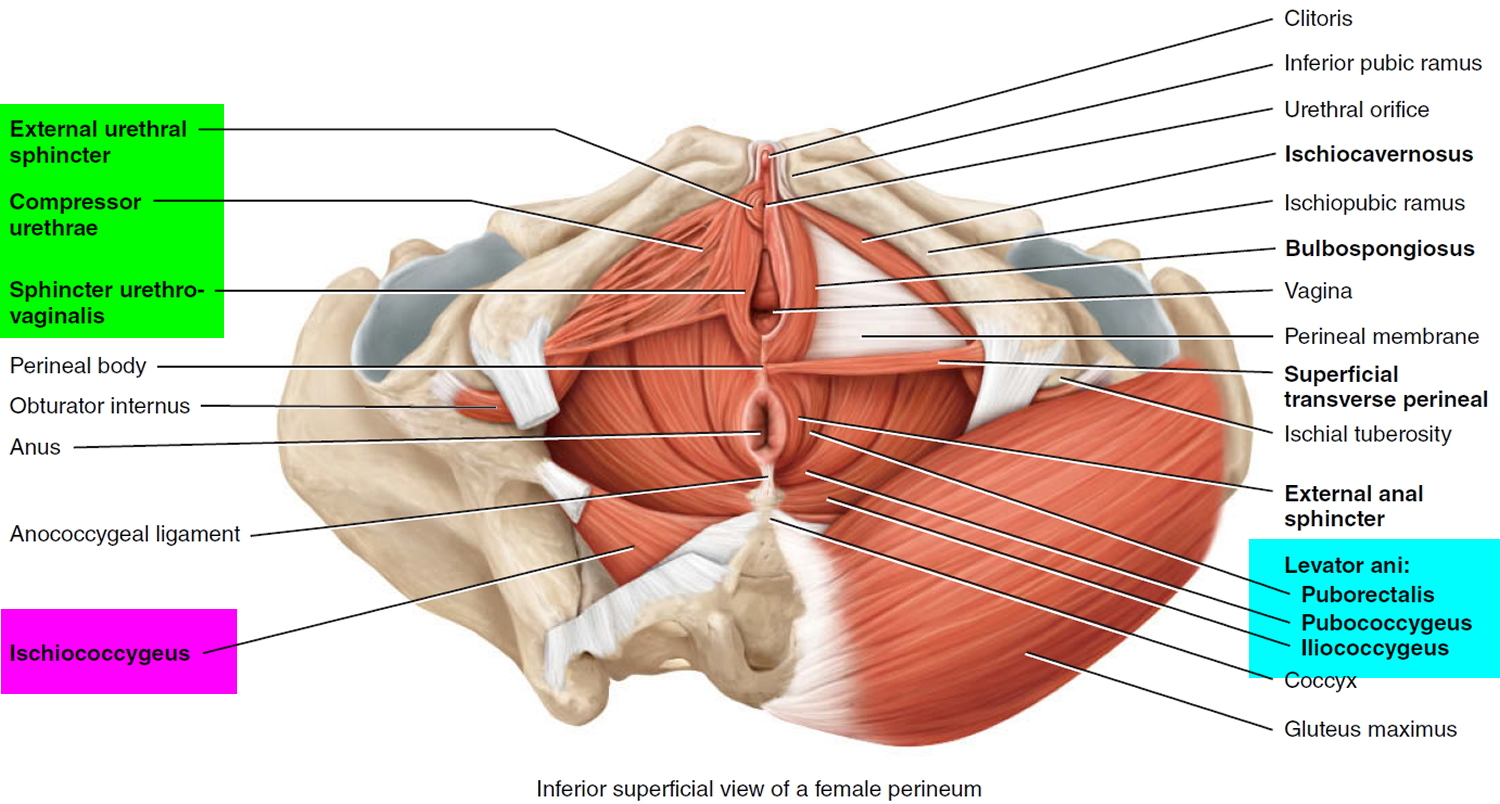

In women without urethral hypermobility, the urethra is stabilized during stress by three interrelated mechanisms. One mechanism is reflex, or voluntary, closure of the pelvic floor. Contraction of the levator ani complex elevates the proximal urethra and bladder neck, tightens intact connective tissue supports, and elevates the perineal body, which may serve as a urethral backstop.

The second mechanism involves intact connective tissue support to the bladder neck and urethra. The pubocervicovesical or anterior endopelvic connective tissue in the area of the bladder neck is attached to the back of the pubic bone, the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, and the perineal membrane. The pubourethral ligaments also suspend the middle portion of the urethra to the back of the pubic bone.

These connective-tissue components form the passive supports to the urethra and bladder neck. During times of increased intra-abdominal pressure, if these supports are intact, they augment the supportive effect of muscular closure of the pelvic floor.

The third mechanism involves 2 bundles of striated muscle, the urethrovaginal sphincter and the compressor urethrae, found at the distal aspect of the striated urethral sphincter. These muscles may aid in compressing the urethra shut during stress maneuvers. These muscles do not surround the urethra, as the striated sphincter does, but lie along the lateral and ventral aspects.

The exact function and importance of these muscles are controversial. Some authors suggest that the urethrovaginal sphincter and the compressor urethrae may provide compression and increased pressure in the distal urethra during times of stress.

Damage to the nerves, muscle, and connective tissue of the pelvic floor is important in the genesis of stress incontinence. Injury during childbirth probably is the most important mechanism. Aging, hypoestrogenism, chronic connective tissue strain due to primary loss of muscular support, activities or medical conditions resulting in long-term repetitive increases in intra-abdominal pressure, and other factors can contribute.

During childbirth, 3 types of lesions can occur: levator ani muscle tears, connective tissue breaks, and pudendal/pelvic nerve denervation. Any of these injuries can occur in isolation but 2 or more in combination are more likely to occur. The long-term result may be the loss of active and passive urethral support and loss of intrinsic urethral tone.

The loss of urethral and bladder neck support may impair urethral closure mechanisms during times of increased intra-abdominal pressure. This phenomenon can be viewed in several ways.

Some hypothesize that under normal circumstances, any increase in intra-abdominal pressure is transmitted equally to the bladder and proximal urethra. This is likely due to the retropubic location of the proximal and mid urethra within the sphere of intra-abdominal pressure. At rest, the urethra has a higher intrinsic pressure than the bladder. This pressure gradient relationship is preserved if acute increases in intra-abdominal pressure are transmitted equally to both organs.

When the urethra is hypermobile, pressure transmission to the walls of the urethra may be diminished as it descends and rotates under the pubic bone. Intraurethral pressure falls below bladder pressure, resulting in urine loss.

Risk factors for stress urinary incontinence

Factors that increase the risk of developing stress incontinence include:

- Age. Physical changes that occur as you age, such as the weakening of muscles, may make you more likely to develop stress incontinence. However, occasional stress incontinence can occur at any age.

- Type of childbirth delivery. Women who’ve had a vaginal delivery are more likely to develop urinary incontinence than women who’ve delivered via a cesarean section. Women who’ve had a forceps delivery to more rapidly deliver a healthy baby may also have a greater risk of stress incontinence. Women who’ve had a vacuum-assisted delivery don’t appear to have a higher risk for stress incontinence.

- Race. Traditionally Caucasian women are thought to be at greater risk than Asian or Negro women. This area remains unclear.

- Body weight. People who are overweight or obese have a higher risk of stress incontinence. Excess weight increases pressure on the abdominal and pelvic organs.

- Previous pelvic surgery. Hysterectomy in women and surgery for prostate cancer in men can weaken the muscles that support the bladder and urethra, increasing the risk of stress incontinence.

- Smoking. Women who smoked are 2-3 times more likely to develop stress incontinence than nonsmokers.

- Connective tissue. Women with stress incontinence have increased number of enzymes that break down the connective tissue. The common enzymes that are increased include collagenases and elastases. They may be related to increased incidence of “stretch marks”, hernias and increased joint flexibility seen in women with pelvic floor dysfunction.

Urethral hypermobility symptoms

Urethral hypermobility is defined as incompetence of the urethral sphincter mechanisms usually associated with stress incontinence symptoms, due to failure of urethral support.

Women with stress urinary incontinence feel a sudden and intense need to urinate, often triggered by activities that place added pressure or stress on their bladder and pelvic floor muscles. Some of the more common activities that can lead to leakage include:

- Coughing

- Sneezing

- Laughing

- Exercising or working out

- Having sex

- Lifting something heavy

- Standing up

- Getting in or out of a car

Leakage may include just a small drop or two of urine or even a whole stream. Any amount is unwanted, so don’t dismiss your concerns simply because your leakage doesn’t seem as bad as it might otherwise be.

Urethral hypermobility complications

Complications of stress incontinence may include:

- Emotional distress. If you experience stress incontinence with your daily activities, you may feel embarrassed and distressed by the condition. It can disrupt your work, social activities, relationships and even your sex life. Some people are embarrassed that they need pads or incontinence garments.

- Mixed urinary incontinence. Mixed incontinence is common and means that you have both stress incontinence and urgency incontinence — the unintentional loss of urine resulting from bladder muscle contractions (overactive bladder) that cause an urgent need to urinate.

- Skin rash or irritation. Skin that is constantly in contact with urine may get irritated or sore and can break down. This happens with severe incontinence if you don’t take precautions, such as using moisture barriers or incontinence pads.

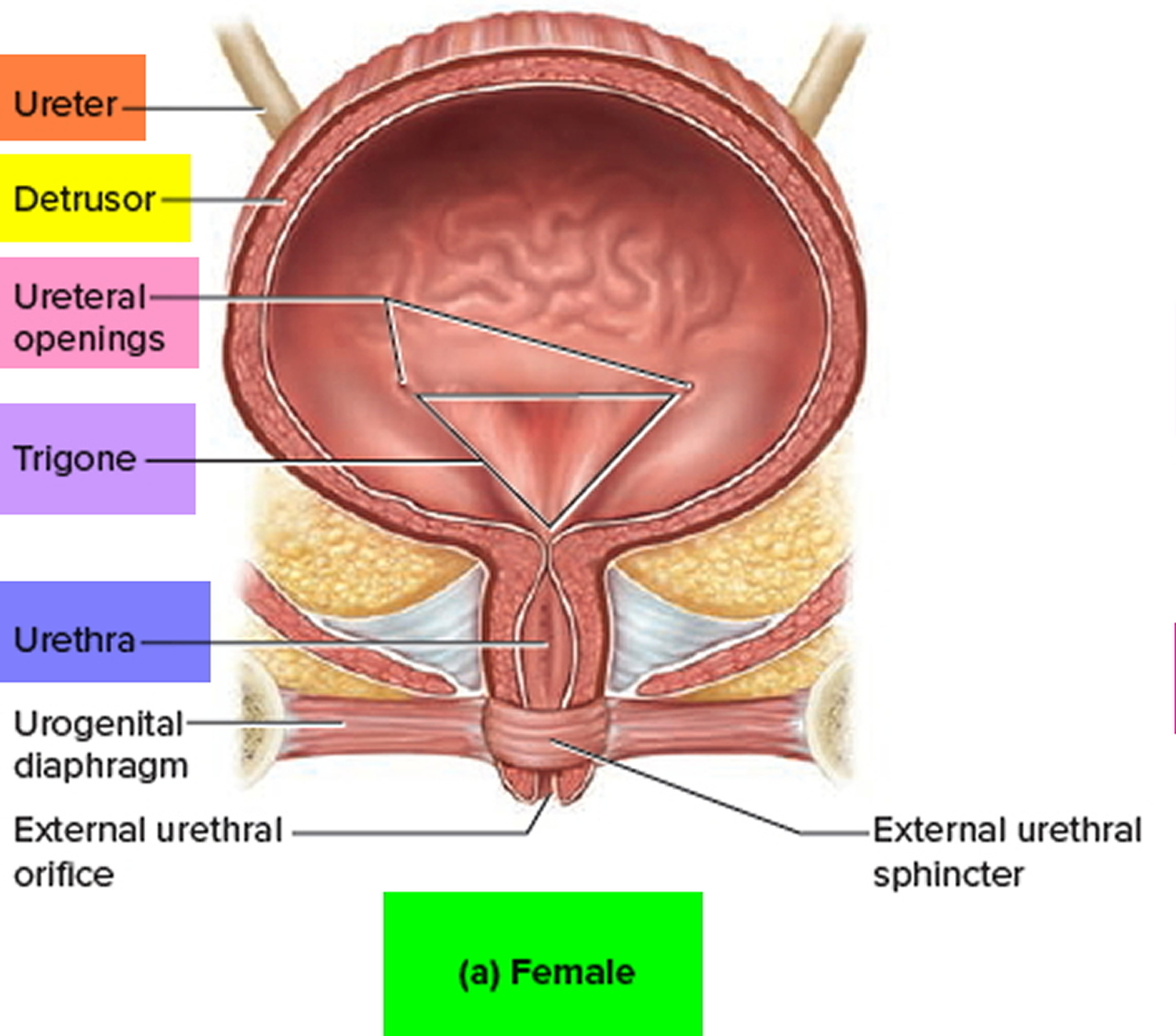

Urethral hypermobility diagnosis

Initial evaluation of any form of incontinence should include 9:

- Detailed history, particularly the genitourinary review of systems

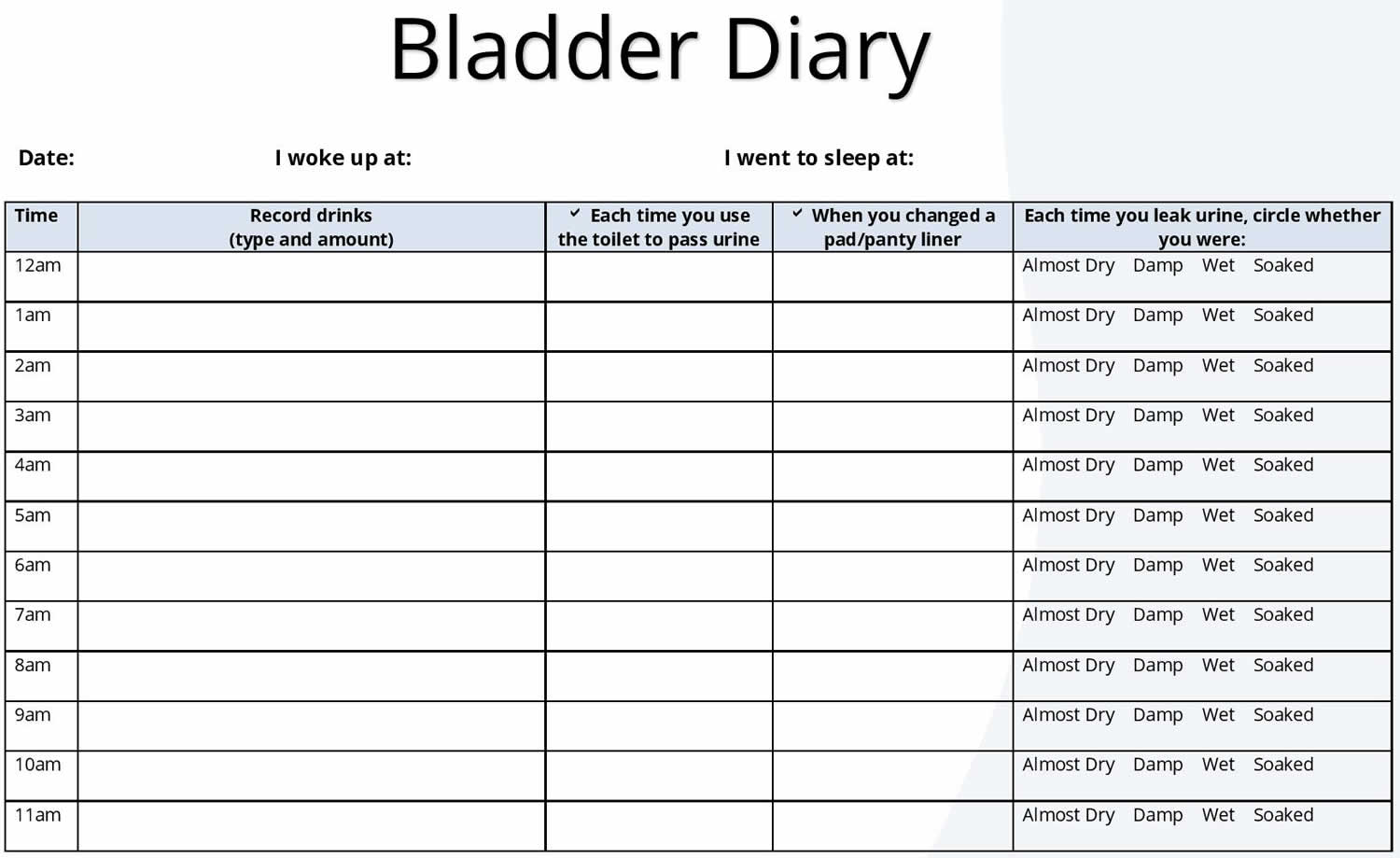

- Voiding diary

- Physical examination with the demonstration of stress incontinence and assessment of urethral hypermobility

- Urinalysis with or without a urine culture

- Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume

- Urodynamic testing is not initially indicated in uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence

A thorough history includes questions about precipitating events, fluid intake pattern, nocturia, type of protective devices used (tampons/pads/diapers), past medical/surgical history, and transient causes (UTIs, hypoestrogenism, cholinergic medications, diabetes, diuretics, psychological stress). A diary of voiding should document at least two days and include the number of accidents with the time of day, amount of fluid intake, amount voided versus leakage, and association of activity 9.

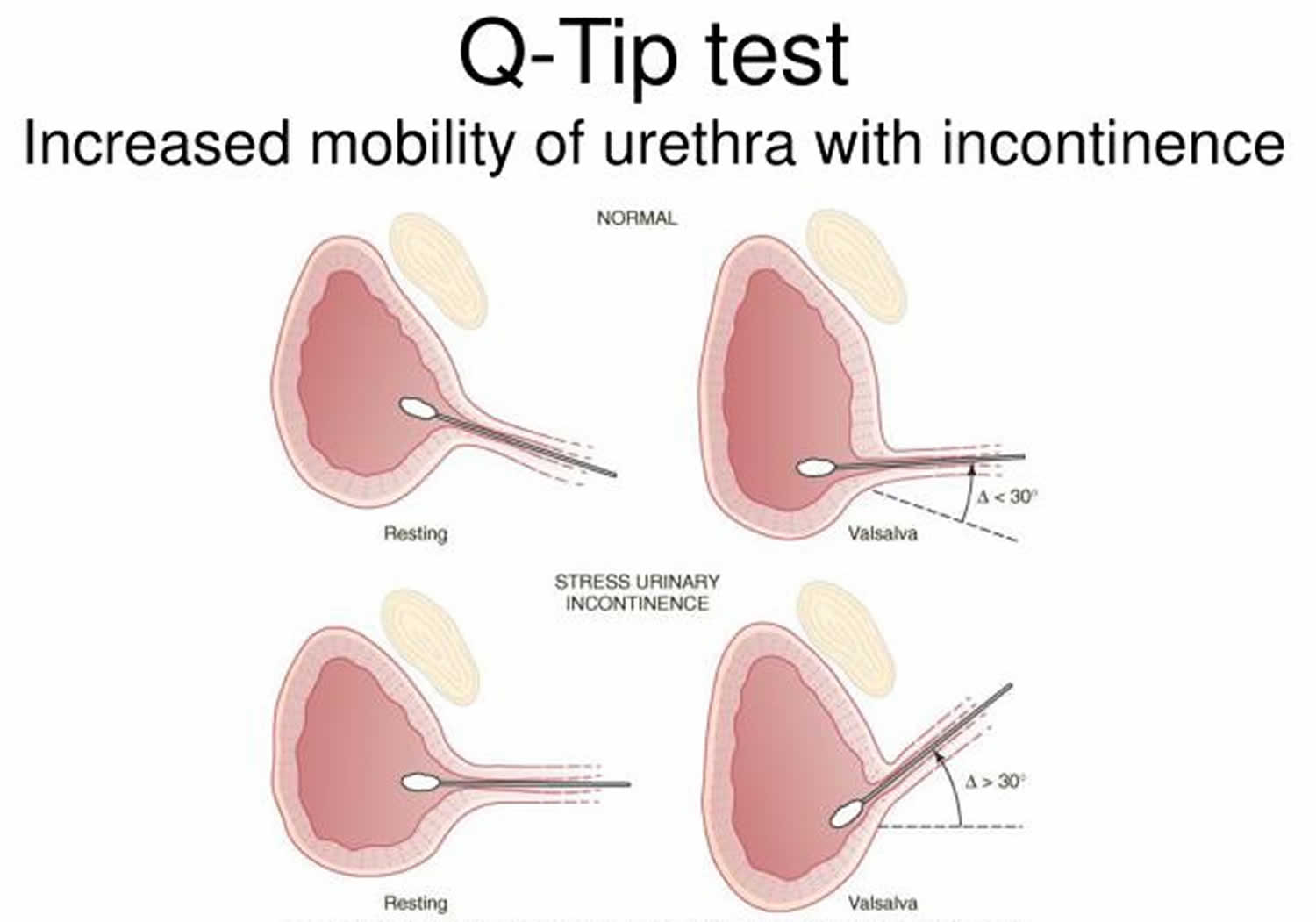

During the general physical examination, the examiner should note if the patient has a large panniculus, prior surgical incisions, or adequate suprapubic muscle tone. The pelvic examination should take place with a full and empty bladder, both standing and supine. The degree of uterine and bladder prolapse should be assessed with a pelvic organ prolapse (POP)-Quantification system 9. The presence of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) beyond the hymen (fourth degree) is consistent with complicated stress urinary incontinence and can either mask or reduce the severity of stress urinary incontinence 10. A positive cough stress test can be used to demonstrate stress urinary incontinence subjectively. The Q-tip test is performed to assess urethral hypermobility which is defined as a 30 degree or more displacement from the horizontal position in the supine position while bearing down 9. A Q-tip test is performed with a cotton-tipped swab to check for urethral hypermobility. A displacement of the urethral angle of at least 30 degrees with Valsalva is suggestive of urethral hypermobility.

Bladder function tests

Indications for urodynamic testing include:

- Complicated stress urinary incontinence

- Failed surgical treatment

- Patients over 60 years old

- Continuous/unpredictable leakage

- History of radical pelvic surgery or pelvic irradiation

Evidence indicates that urodynamic testing is not necessarily needed before surgical management because it may not affect treatment outcomes 9.

Bladder function tests may include:

- Measurements of post-void residual urine. Your doctor may recommend this test if there’s concern about your ability to empty your bladder completely, particularly if you are older, have had prior bladder surgery or have diabetes. This test can tell how well your bladder is functioning. A specialist uses an ultrasound scan, which translates sound waves into an image, to view how much urine is left in your bladder after you urinate. In some cases, a thin tube (catheter) is passed through the urethra and into your bladder. The catheter drains the remaining urine, which can then be measured.

- Measuring bladder pressures. Cystometry is a test that measures pressure in your bladder and in the surrounding region as your bladder fills. Your doctor may recommend this test to check for stress incontinence if you have had a neurologic disease of the spinal cord. A catheter is used to fill your bladder slowly with warm fluid. As your bladder fills, you may be asked to cough or bear down to test for leaks. This procedure may be combined with a pressure-flow study, which tells how much pressure your bladder has to exert in order to empty completely.

- Creating images of the bladder as it functions. Video urodynamics is a test that uses imaging to create pictures of your bladder as it’s filling and emptying. Warm fluid mixed with a dye that shows up on X-rays is gradually instilled in your bladder by a catheter while the images are recorded. When your bladder is full, the imaging continues as you urinate to empty your bladder.

- Cystoscopy. This test uses a scope that is inserted into the bladder to look for blockages or any abnormalities in the bladder and urethra. This procedure is usually completed in the office.

You and your doctor should discuss the results of any tests and decide how they impact your treatment strategy.

Urethral hypermobility test

Simple office incontinence testing should be utilized to help differentiate the 3 types of urinary incontinence. A positive cough stress test in both the sitting and supine positions is highly diagnostic for stress incontinence. Vaginal prolapse may mask or decrease incontinence symptoms; therefore, it is important to elevate the areas of prolapse surrounding the urethra and check for incontinence with stress (Marshall Test). A Q-tip test is performed with a cotton-tipped swab to check for urethral hypermobility. A displacement of the urethral angle of at least 30 degrees with Valsalva is suggestive of urethral hypermobility. A urinalysis and culture should be sent for any infectious process such as cystitis. A post-void residual urine volume is measured to check for overflow incontinence. Indications for multi-channel urodynamics include:

- Abnormal office cystometry tests

- Continuous, unpredictable leakage

- Pelvic radiation

- History of radical pelvic surgery

- Previous incontinence surgery 11

Figure 4. Q-tip test urethral hypermobility

Urethral hypermobility treatment

Treatment of stress urinary incontinence subdivides into behavioral, pharmacological, and surgical management. Regardless of whether the patient desires any of the three options, all patients should receive counseling on lifestyle modifications. Bladder irritants to avoid include caffeinated beverages (coffee, tea, sodas) alcohol, citrus fruits, chocolate, tomato, spicy foods, and tobacco.

Behavioral modifications and noninvasive options include:

- Pelvic muscle exercises such as Kegel exercises – three sets of ten pelvic musculature contractions held for ten seconds three times a day

- Bladder retraining (timed voiding) – regularly scheduling urination leading to an empty bladder for longer periods throughout the day (see Figure 4). Bladder retraining can lessen the amount of fluid you have in your bladder and also help condition your bladder to hold urine for longer periods of time.

- Biofeedback – visual or audio signals can provide feedback to properly contract pelvic floor muscles. Biofeedback is often done in conjunction with kegels. A physical therapist may use a biofeedback instrument to measure you pelvic floor strength, and monitor your improvement.

- Electrostimulation – via acupuncture needles for 30 minutes weekly for 12 weeks followed by monthly maintenance sessions. This therapy delivers a small amount of electrical stimulation to the nerves and muscles of the pelvic floor and bladder to help them tighten or contract, thereby strengthening them.

- Injection therapy. This technique uses a bulking agent that’s injected into the tissues around the urethra to help close the sphincter without interfering with urination, helping to reduce leaks.

- Urethral inserts. This small tampon-like disposable device inserted into the urethra acts as a barrier to prevent leakage. It’s usually used to prevent incontinence during a specific activity, but it may be worn throughout the day. Urethral inserts can be worn for up to eight hours a day. Urethral inserts are generally used only for heavy activity, such as repeated lifting, running or playing tennis.

- Vaginal pessaries – the most common pessaries used for stress urinary incontinence are the ring and Gellhorn pessary

- Pessaries aid in elongating and elevating the urethrovesical angle

- Proper fitting is necessary

- If the pessary is too tight, it may cause urinary obstruction with subsequent urinary retention, and if the pessary is too small, it usually will fall out soon after placement

- Lose excess weight. Obesity is a risk factor in developing stress urinary incontinence due to the extra pressure placed on the pelvic floor and the bladder. Following a healthy diet and losing weight can help ease symptoms.

- Quit Smoking. You already know that smoking can cause or contribute to more diseases than we could ever list here, but you might not realize that it’s also a real factor in the development of stress urinary incontinence. All that coughing can put stress on your pelvic floor, and that can lead to muscle weakness and leakage. Smoking is also a factor in many cases of bladder cancer. Just one more reason why quitting today can make a meaningful difference in your life.

- Add fiber to your diet. If chronic constipation contributes to your urinary incontinence, keeping bowel movements soft and regular reduces the strain placed on your pelvic floor muscles. Try eating high-fiber foods — whole grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables — to relieve and prevent constipation.

- Avoid foods and beverages that can irritate your bladder. If eating chocolate or drinking coffee, tea (regular or decaf) or carbonated beverages seems to make you urinate and leak more frequently, try eliminating that drink, especially on days you really don’t want to be bothered by leakage.

Pharmacological options include:

- Oxybutynin – anti-cholinergic that blocks the muscarinic receptor in the smooth muscle of the bladder inhibiting detrusor contractions

- Tricyclic anti-depressants – have alpha-adrenergic effects that aid in urethral contraction and closure

- Estrogen – applied topically to increase urethral blood flow and sensitivity of alpha-adrenergic receptors.

Figure 5. Bladder diary

Sexuality and incontinence

Leaking urine during sexual intercourse can be upsetting, but it doesn’t necessarily have to get in the way of intimacy and enjoyment:

- Talk with your partner. As difficult as this may be initially, be upfront with your partner about your symptoms. A partner’s understanding and willingness to accommodate your needs can make your symptoms much easier to handle.

- Empty your bladder beforehand. To reduce your chances of leakage, avoid drinking fluids for an hour or so before sex and empty your bladder before intimacy starts.

- Try a different position. Altering positions may make leakage less likely for you. For women, being on top generally gives better control of the pelvic muscles.

- Do your Kegel exercises. These exercises strengthen your pelvic floor muscles and reduce urine leakage.

- Be prepared. Having towels handy or using disposable pads on your bed may ease your worry and contain any leakage.

Urethral hypermobility incontinence surgery

There is no single surgical procedure for the treatment of all patients with stress urinary incontinence. The surgery must be tailored for the patient, not the reverse. Prophylactic incontinence procedure should be considered for patients with prolapse without stress urinary incontinence since post-operative voiding dysfunction may occur with an anterior colporrhaphy.

The goals of surgery for stress incontinence include reinforcing the pubourethral ligaments and the paraurethral connective tissue at the mid-urethra. Surgical treatment generally divides into abdominal procedures (open or laparoscopic), vaginal procedures, and urethral bulking agents. The most successful revolve around a “sling” that offers support and stability.

- Sling procedure: This is the most common procedure performed in women with stress urinary incontinence. In this procedure, the surgeon uses the person’s own tissue, synthetic material (mesh), or animal or donor tissue to create a sling or hammock that supports the urethra.

- Injectable bulking agents. Synthetic polysaccharides or gels may be injected into tissues around the upper portion of the urethra. These materials bulk up the area around the urethra, improving the closing ability of the sphincter.

- Retropubic colposuspension. This surgical procedure uses sutures attached to ligaments along the pubic bone to lift and support tissues near the bladder neck and upper portion of the urethra. This surgery can be done laparoscopically or by an incision in the abdomen.

- Inflatable artificial sphincter. This surgically implanted device is used to treat men. A cuff, which fits around the upper portion of the urethra, replaces the function of the sphincter. Tubes connect the cuff to a pressure-regulating balloon in the pelvic region and a manually operated pump in the scrotum.

Abdominal procedures include 12:

- Marshall Marchetti Krantz (MMK) – retropubic approach elevating and fixating the anterolateral part of the urethra to the posterior pubic symphysis and adjacent periosteum of the pubic bone

- Burch colposuspension – the bladder neck is supported with a few stitches placed on either side of the urethra and the iliopectineal (Cooper’s) ligament

- Pubovaginal sling – a strip of rectus fascia or fascia lata is placed directly under the bladder neck via the retropubic space and secured at the level of the rectus abdominis fascia

An abdominal approach is indicated if there is a large uterus compressing the bladder necessitating concomitant hysterectomy, no vaginal prolapse, adnexal pathology, or failed vaginal incontinence surgery. Vaginal surgery should be considered when vaginal prolapse is present, a history of failed abdominal surgery, or the patient is high risk for abdominal surgery (multiple abdominal incisions, morbid obesity).

Vaginal procedures include 13:

- Modified Pereyra Procedure (MPP)- elevation of paraurethral tissue to the abdominal wall creating a significant elevation of the urethrovesical angle

- Mid-urethral sling procedures – polypropylene mesh is placed under the mid-urethra, the more critical continence zone – the open-weave mesh stabilizes and promotes ingrowth of the collagen over time

- Trans-vaginal tape (TVT)- retropubic – the mesh insertion is through the retropubic space and exits out the abdominal wall suprapubically

- Transvaginal Tension Free Vaginal Tape-Obturator (TVT-O) – “inside-out” placement of the mesh from the vagina through the obturator foramen out through the skin of the groin

Modified Pereyra Procedure and Marshall Marchetti Krantz can be considered as primary or secondary treatment and may be an adjunct with vaginal vault repair for prolapse. Urethral slings have become the most common type of surgery to correct stress urinary incontinence. Advantages of the TVT sling include procedure completion in as little as 30 minutes with same day discharge, no post-operative urinary catheterization, short recovery time, and minimal pain. A benefit of the TVT-retropubic compared to TVT-O is avoidance of bleeding from the medial branches of obturator vessels while TVT-O decreases the risk of bladder injury.

If significant uterine procidentia exists, a vaginal hysterectomy should be performed followed by retropubic suspension. If pelvic pressure symptoms exist with stress urinary incontinence, check and correct for cystocele, enterocele or rectocele with an anterior repair, enterocele repair or posterior colpoperineoplasty, respectively.

Urethral bulking is the injection of synthetic materials (i.e., collagen) into the urethral mucosal layer to provide support and tighten the bladder neck’s opening. This procedure is done in an office setting with local anesthesia. Two to three injections may be required to improve symptoms 14.

Postoperative and rehabilitation care

Postoperative patients may require prolonged catheterization either with an urethral or suprapubic catheter. Postvoid residual urine should be at most be less than 100 mL. Any voiding dysfunction after catheter removal usually resolves spontaneously within a few days or weeks. Coital activity should be avoided at least 6 weeks postop to avoid disruption of the surgical site till healing is complete. The patient should be told no heavy lifting greater than 25 lbs to avoid increasing intraabdominal pressure that may give rise to recurrent prolapse and incontinence.

Complications

The risk of surgical treatment for stress urinary incontinence include:

- Infection

- Bleeding with transfusion

- Injury to the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract

- Postop dyspareunia 15

- Persistent or recurrent urinary incontinence or prolapse

Urethral hypermobility prognosis

The prognosis of a patient with incontinence is excellent with current health care. With improvement in information technology, well-trained medical staff, and advances in modern medical knowledge, patients with incontinence should not experience the morbidity and mortality of the past. Although the ultimate well-being of a patient with urinary incontinence depends on the precipitating condition, urinary incontinence itself is easily treated and prevented by properly trained health care personnel.

Stress urinary incontinence can exert a significant impact on a patient’s life. Treatment aims at improving the quality of life. Complete resolution of stress urinary incontinence may not be feasible, and a combination of behavioral, pharmacological, and surgical treatment may be necessary. In stress urinary incontinence, the improvement rate with alpha-agonists is 19-74%; improvement rates with muscle exercise and surgery, improvement rates are 87% and 88%, respectively 16.

Some patients may be satisfied with improved stress urinary incontinence without complete resolution especially if it avoids surgery. Cure rates with pelvic floor muscle exercises have been reported to be 58.8% at 12 months 17. Pessaries may improve symptoms in 33% of patients 18. There is no evidence that estrogen is efficacious in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence but may help increase blood flow to paraurethral receptors and thicken an atrophic vagina if planning vaginal surgery 19. Symptom control with anticholinergics has been reported to be 49% 17. Overall, surgical treatment has a cure rate of 84% (source: urinary incontinence). One randomized trial found no difference in success rates between the Burch colposuspension and the retro public mid-urethral sling at 6 months and 5 years 20. Five-year follow-up studies of the TVT have found cure rates of 57.4-83%, improvement rates of 7.6% to 17%, and failure rates of 9.1 to 25.6% 21. One study found results between the Modified Pereyra Procedure (MPP) and Marshall Marchetti Krantz (MMK) comparable with 84% of Modified Pereyra Procedure (MPP) patients cured compared to 86.6% of MMK patients 15. In that same study, 9.8% of MPP patients improved compared to 6.6% of Marshall Marchetti Krantz (MMK), and 6.2% of Modified Pereyra Procedure (MPP) patients failed compared to 6.8% of Marshall Marchetti Krantz (MMK) patients 15. Urethral bulking injections have reported cure rates between 24.8% to 36.9% at 12-month follow-up 17.

Without effective treatment, urinary incontinence can have an unfavorable outcome. Prolonged contact of urine with the unprotected skin causes contact dermatitis and skin breakdown. If left untreated, these skin disorders may lead to pressure sores and ulcers, possibly resulting in secondary infections.

The medical morbidity includes includes the following:

- Perineal candidal infections

- Cellulitis

- Pressure sores

- Constant skin irritation and moisture

- Falls and subsequent fractures from slipping on urine

- Sleep deprivation from nocturia

Psychological morbidity includes the following:

- Poor self-esteem

- Social withdrawal

- Depression

- Sexual dysfunction from embarrassment

- Curtailed social and recreational activities

For individuals with a decompensated bladder that does not empty well, the postvoid residual urine can lead to overgrowth of bacteria and subsequent urinary tract infection (UTI). Untreated UTIs may lead to urosepsis and death.

Patients whose urinary incontinence is treated with catheterization also face risks. Both indwelling catheters and intermittent catheterization have a range of potential complications.

Urinary incontinence is a leading cause of admission to a nursing home when families find it too difficult to care for a relative with incontinence.

A study by Foley et al 22 looked at the connection between urinary symptoms, poor quality of life, and physical limitations and falls among elderly individuals. These authors found that urinary incontinence and falling had an impact on quality of life and were, in fact, associated with physical limitations.

References- BergmanA, McCarthy TA, Ballard CA, Yanai J. Role of the Q-tip test in evaluating stress urinary incontinence. J Reprod Med1987;32:273–275.

- MR Imaging of the Female Urethra and Supporting Ligaments in Assessment of Urinary Incontinence: Spectrum of Abnormalities. Katarzyna J. Macura, Rene R. Genadry, and David A. Bluemke. RadioGraphics 2006 26:4, 1135-1149 https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/full/10.1148/rg.264055133

- Delancey JO, Ashton-Miller JA. Pathophysiology of adult urinary incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004 Jan. 126(1 Suppl 1):S23-32.

- Dietz HP, Wilson PD. Anatomical assessment of the bladder outlet and proximal urethra using ultrasound and videocystourethrography. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1998. 9(6):365-9.

- Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ., Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311-6.

- Minassian VA, Yan X, Lichtenfeld MJ, Sun H, Stewart WF. The iceberg of health care utilization in women with urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Aug;23(8):1087-93.

- Offermans MP, Du Moulin MF, Hamers JP, Dassen T, Halfens RJ. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated risk factors in nursing home residents: a systematic review. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2009;28(4):288-94.

- Shamliyan T, Wyman J, Bliss DZ, Kane RL, Wilt TJ. Prevention of urinary and fecal incontinence in adults. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007 Dec;(161):1-379.

- Committee Opinion No. 603: Evaluation of uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence in women before surgical treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;123(6):1403-7.

- Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, Shull BL, Smith AR. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996 Jul;175(1):10-7.

- Rosier PF, Gajewski JB, Sand PK, Szabó L, Capewell A, Hosker GL., International Consultation on Incontinence 2008 Committee on Dynamic Testing. Executive summary: The International Consultation on Incontinence 2008–Committee on: “Dynamic Testing”; for urinary incontinence and for fecal incontinence. Part 1: Innovations in urodynamic techniques and urodynamic testing for signs and symptoms of urinary incontinence in female patients. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2010;29(1):140-5.

- Lapitan MC, Cody JD, Grant A. Open retropubic colposuspension for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Oct 07;(4):CD002912

- Ford AA, Rogerson L, Cody JD, Aluko P, Ogah JA. Mid-urethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul 31;7:CD006375

- McGuire EJ. Urethral bulking agents. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2006 May;3(5):234-5.

- Riggs JA. Retropubic cystourethropexy: a review of two operative procedures with long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 1986 Jul;68(1):98-105.

- Castillo PA, Espaillat-Rijo LM, Davila GW. Outcome measures and definition of cure in female stress urinary incontinence surgery: a survey of recent publications. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2010 Mar. 21(3):343-8.

- Riemsma R, Hagen S, Kirschner-Hermanns R, Norton C, Wijk H, Andersson KE, Chapple C, Spinks J, Wagg A, Hutt E, Misso K, Deshpande S, Kleijnen J, Milsom I. Can incontinence be cured? A systematic review of cure rates. BMC Med. 2017 Mar 24;15(1):63.

- Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, Nygaard IE, Ye W, Weidner A, Bradley CS, Handa VL, Borello-France D, Goode PS, Zyczynski H, Lukacz ES, Schaffer J, Barber M, Meikle S, Spino C., Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Mar;115(3):609-17.

- Cody JD, Jacobs ML, Richardson K, Moehrer B, Hextall A. Oestrogen therapy for urinary incontinence in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;10:CD001405

- Ward KL, Hilton P., UK and Ireland TVT Trial Group. Tension-free vaginal tape versus colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence: 5-year follow up. BJOG. 2008 Jan;115(2):226-33.

- Liapis A, Bakas P, Creatsas G. Long-term efficacy of tension-free vaginal tape in the management of stress urinary incontinence in women: efficacy at 5- and 7-year follow-up. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008 Nov;19(11):1509-12.

- Foley AL, Loharuka S, Barrett JA, et al. Association between the Geriatric Giants of urinary incontinence and falls in older people using data from the Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study. Age Ageing. 2012 Jan. 41(1):35-40.