Urethral injury

Urethral injury is when the urethra is hurt by force. The mechanisms of injury ranges from gunshot wounds to self-inflicted sexual misadventures. Urethral injury can first be classified based on location as either anterior or posterior urethra 1. Posterior urethral injuries are located in the membranous and prostatic urethra. Injuries to the anterior urethra are located distal to the membranous urethra.

Trauma to the anterior urethra is often from “straddle injury” coming down hard on something between your legs, such as a bicycle seat or crossbar, a fence, or playground equipment, with the bulbar urethra the most common location affected resulting in significant contusion to the spongiosus with possible significant hematoma of the perineum 2. This type of trauma can lead to scars in the urethra (“urethral stricture”). These scars can slow or block the flow of urine from the penis.

Trauma to the posterior urethra almost always results from a severe injury such as pelvic fracture and less frequently from iatrogenic trauma during pelvic surgeries. Pelvic-fracture associated urethral injuries are present in 1.5% –10% of injuries resulting in fracture of the pelvis 3. High-speed motor vehicle accidents are the most common mechanism of injury here 4, though fall from height is another common mechanism resulting in pelvic fracture and pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury. In males, posterior urethral trauma may tear the urethra completely away below the prostate. These wounds can form scar tissue that slows or blocks the urine flow. Given the relative complexity of pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury and fact that it’s three times more common in the setting of trauma than anterior urethral injury 5, it is of utmost importance that pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury patients receive adequate followup, as many will develop genitourinary complications as a result of their injury; these complications may include stricture formation, urethrocutaneous fistula, erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, and pain. In their guidelines, the American Urological Association 6 states that patients should be surveyed for at least one year using some combination of uroflowmetry, retrograde urethrogram, and/or cystoscopy. The European Association of Urology guidelines 7 make no specific reference to followup after primary realignment for pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury.

For females, urethral injuries are rare. They’re always linked to pelvic fractures or cuts, tears, or direct trauma to the body near the vagina. Urethral injuries in females can also be caused by sexual assault.

Urethral injury can also result from objects piercing the sex organs or pelvis.

Will urethral injury or the surgery cause problems with sex?

Surgery to fix the urethra rarely causes erectile dysfunction. But severe posterior injuries can also harm the delicate nerves that run beside the urethra deep within the body. These nerves send the signal to the penis to become erect for sex. About 5 out of 10 men who have urethral injuries from pelvic fractures will have some type of erectile dysfunction once they heal. This may range from very mild to full erectile dysfunction. But there are many ways to treat this.

Will urethral injury or the surgery cause me to leak urine?

A small number of patients (2 to 5 out of 100) have problems with incontinence after having posterior urethral trauma fixed. This is thought to be caused by damage to the nerves that control the bladder outlet. This damage is a result of the injury and not from the surgery.

Urethra anatomy

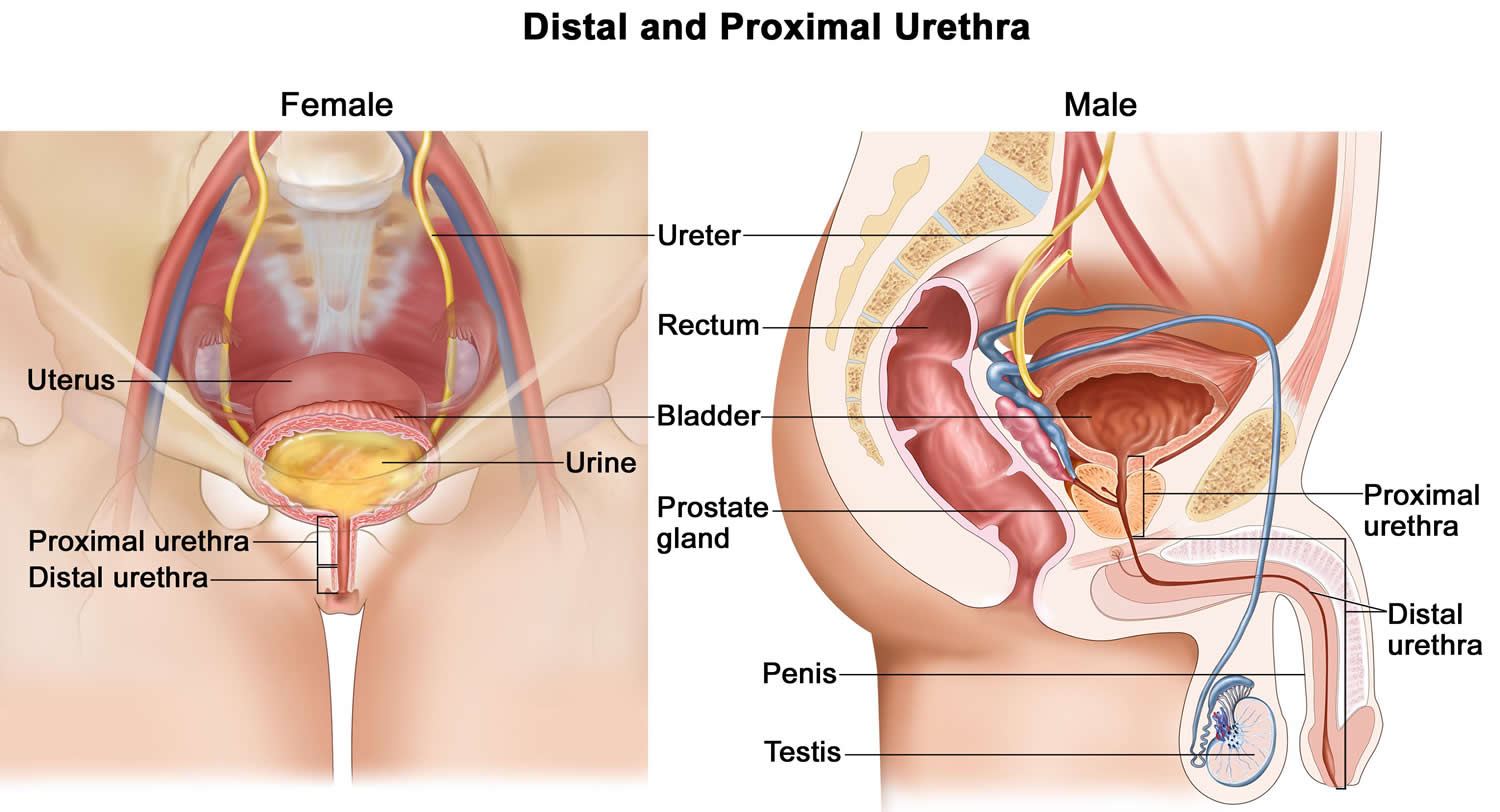

The urethra is a tube-like organ that carries urine from the bladder out of the body. In males, the urethra starts at the bladder and runs through the prostate gland, perineum (the space between the scrotum and the anus), and through the penis. The anterior (“front”) urethra goes from the tip of the penis through the perineum. The posterior (“back”) urethra is the part deep within the body.

In females, the urethra is much shorter, in adults, it is about 4 cm in length: it runs from the bladder to just in front of the vagina within the anterior vaginal wall. It opens outside the body. Normal urine flow is painless and can be controlled. The stream is strong and the urine is clear with no visible blood.

The male urethra, which averages about 20 cm in length, is divided into distal and proximal portions. The distal urethra, which extends distally to proximally from the tip of the penis to just before the prostate, includes the meatus, the fossa navicularis, the penile or pendulous urethra, and the bulbar urethra. The proximal urethra, which extends from the bulbar urethra to the bladder neck, includes distally to proximally the membranous urethra and the prostatic urethra.

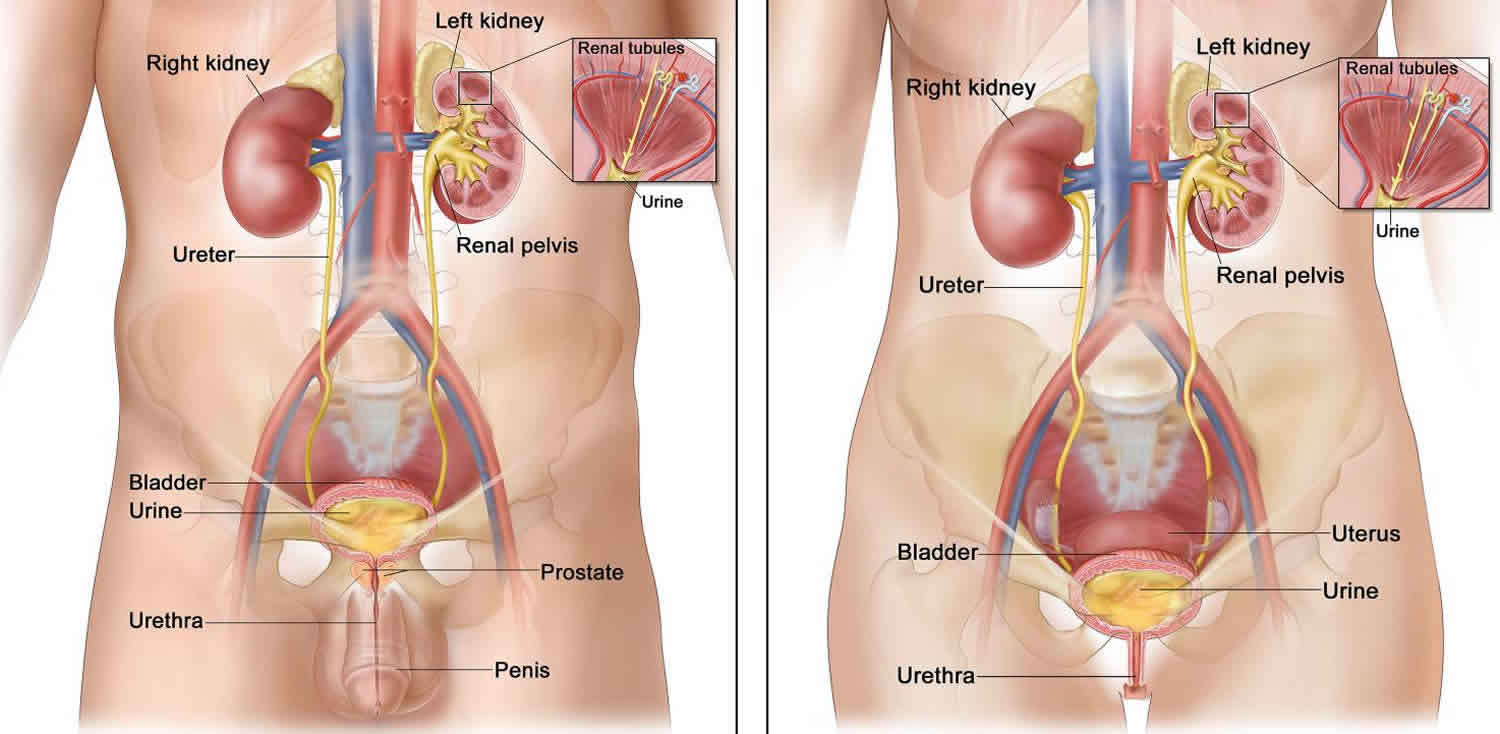

Figure 1. Urethra anatomy

Footnote: Anatomy of the male urinary system (left panel) and female urinary system (right panel) showing the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. Urine is made in the renal tubules and collects in the renal pelvis of each kidney. The urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the bladder. The urine is stored in the bladder until it leaves the body through the urethra.

Urethral trauma causes

The cause of a urethral injury can be classified as blunt or penetrating. In the posterior urethra, blunt injuries are almost always related to massive deceleration events such as falls from some distance or vehicular collisions. These patients most often have a pelvic fracture involving the anterior pelvis 8.

Blunt injury to the anterior urethra most often results from a blow to the bulbar segment such as occurs when straddling an object or from direct strikes or kicks to the perineum 9. Blunt anterior urethral trauma is sometimes observed in the penile urethra in the setting of penile fracture.

Penetrating trauma most often occurs to the penile urethra. Causes include animal bites 10, gunshot and stab wounds. Insertion of foreign bodies is another rare cause of anterior injury. It is usually a result of autoerotic stimulation or may be associated with psychiatric disorders 7.

Iatrogenic injuries to the urethra occur when difficult urethral catheterization leads to mucosal injury with subsequent scarring and stricture formation. Catheter placement is the most common cause of iatrogenic urethral trauma. Iatrogenic urethral injuries also occur after radical prostatectomy, pelvic radiotherapy, and other abdominopelvic surgery 11.

Anterior urethral injury

Trauma to the anterior urethra can be caused by straddle injuries—coming down hard on something between your legs, such as a bicycle seat or crossbar, a fence, or playground equipment.

Posterior urethral injury

Trauma to the posterior urethra can be caused by pelvic fractures from:

- Car crashes

- Crush injuries

- Falls from very high heights

- Bullets or knives

For females, urethral injuries can also be caused by sexual assault.

Urethral trauma symptoms

Trauma to the urethra can allow urine to leak into the tissues around it. This can cause:

- Swelling

- Inflammation

- Infection

- Pain in the belly

Other signs of urethral trauma are:

- Not being able to pass urine

- Urine building up in the bladder

- Blood in the urine (“hematuria”)

For males, the most common sign of a problem is blood – even a drop – at the tip of the penis. Swelling and bruising of the penis, scrotum, and perineum may also occur, along with pain in that area.

Urethral trauma diagnosis

If you have blood at the end of the penis or in the urine or can’t pass urine after an injury to the urethral area, you should see a health care provider right away. Blood at the urethral meatus is a common finding in the presence of a urethral injury and pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury, although its absence does not rule one out 12.

Other findings on inspection may include ecchymosis (bruising) of the scrotum and/or perineum, while in women, urethral injury should be suspected in the presence of labial edema or blood at the introitus. Given that urinary retention is another common presenting symptom of pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury, the bladder may be distended and palpable on abdominal exam. Digital rectal exam findings in the setting of urethral trauma may vary from impalpable, particularly in the acute phase of pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury 12 secondary to presence of a pelvic hematoma obscuring the prostate to palpation 13 or “high-riding” in the case of a partial or complete posterior urethral disruption. Furthermore, digital rectal exam should be performed to rule out a rectal injury 14.

Your health care provider may try to pass a tube (“catheter”) through your urethra. Not being able to pass a tube into the urethra is the first sign of urethral injury. An x-ray is done after squirting a special dye into the urethra. The dye is used to be seen on an x-ray. X-rays are taken to see if any of the dye leaks out of the urethra inside your body. This would mean there’s an injury. An x-ray of the urethra is often done after a pelvic fracture, because urethral injury is common in these cases (about 1 in 10 cases).

Imaging and flexible cystoscopy

Plain-film or scout fluoroscopy imaging of the pelvis can identify pelvic fracture or presence of foreign bodies in the genitourinary tract 15 but has no role in diagnosing urethral injury directly. Furthermore, although potentially useful in the acute trauma setting for ruling out concomitant injuries or in the scenario where a suprapubic catheter is to be placed, there is no role for use of ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the diagnosis of pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury in the acute setting.

Retrograde urethrogram is the diagnostic imaging study of choice in the setting of suspected urethral injury. Partial disruption of the urethra is suggested with active extravasation of contrast with simultaneous bladder filling, while a complete disruption is suggested in the setting of contrast extravasation without visualization of contrast in the bladder 12. While the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma staging of urethral injury remains the gold standard staging system 16, Chapple et al 5 suggested a simpler, practical classification system based on retrograde urethrogram findings in their 2004 consensus statement on urethral injury. A retrograde urethrogram will help identify the location and extent of urethral injury and can be helpful in guiding subsequent management decisions.

Bedside flexible cystoscopy may be performed in the acute setting of suspected urethral injury as a diagnostic adjunct with potential for intervention; it can help identify a partial vs. complete urethral injury while primary realignment with a urethral catheter may be performed with placement of a wire across the injured area 17. Bladder drainage is paramount in the acute management of pelvic-fracture associated urethral injury and primary realignment has been associated with improved outcomes compared with suprapubic catheter drainage only in terms of eventual stricture severity 18. Thus, an attempt at primary realignment via bedside flexible cystoscopy is a reasonable and commonly used manoeuvre, recognizing that in the setting of an unstable patient, bladder drainage with suprapubic catheter placement may be more appropriate.

Urethral injury treatment

The treatment for urethral trauma depends on where and how bad the injury is. Many cases of anterior urethral injury need to be fixed right away with surgery.

Minor anterior urethral injury can be treated with a catheter through the urethra into the bladder 19. This keeps urine from touching the urethra so it can mend. The catheter is often left in place for 14 to 21 days. After that time, an x-ray is taken to see if the injury has healed. If it has healed, the catheter can be taken out in the doctor’s office. If the x-ray still shows leaks, the catheter is left in longer.

If serious urethral trauma is seen on the x-ray, a tube is used to carry urine away from the injured area to keep it from leaking. Urine leaking inside the body can cause:

- Swelling

- Inflammation

- Infection

- Scarring

The treatment of a posterior urethral injury is very complicated. This is because it’s almost always seen with other severe injuries. Unfortunately, it means that this problem can’t be fixed right away. Most urologists first place a catheter in the bladder at the time of injury and wait for 3 to 6 months. This gives the body time to reabsorb the bleeding from the pelvic fracture. It’s also easier to fix the urethra after swelling in the tissues from a pelvic injury has gone down. Most posterior urethral injuries need an operation to connect the 2 torn edges of the urethra. This is most often done through a cut in the perineum.

If the urethra has completely torn away, urine must be drained. This is done with a tube stuck into the bladder through the skin (“suprapubic catheter drainage”). This Foley catheter goes through the skin just above the pubic bone in the lower belly into the bladder. This is most common after severe injuries. The tube can be put in at the time of abdominal surgery for other repairs. Or it can be done through a small puncture. An x-ray can be used to see that the catheter is in the bladder. Your doctor may suggest a procedure to rejoin the torn urethra over a catheter, which may help it heal.

After treatment

If surgery was done, the catheter left in the bladder can be uncomfortable. Also, the catheter can bother the bladder and cause it to contract on its own, which can hurt. This can also cause some blood to be seen in the urine. These symptoms often clear up after the catheter is taken out.

The most common problem after urethral repair is scarring in the urethra. The scars can partly block the urine flow, causing the stream to be weak. You may also have to strain to urinate. Your urologist can often fix this by widening the scarred section. This is done with instruments placed through the urethra. Sometimes the surgery needs to be done again to keep the urethra open.

If you had a pelvic fracture urethral injury, your urologist will arrange follow-up visits. These are to make sure you don’t develop erectile dysfunction, or urine control problems.

Will I need further surgery after my operation for a posterior urethral injury?

Most patients don’t need further surgery or expansion of urethral scarring after repair.

Urethral trauma prognosis

Men with urethral injuries have an excellent prognosis when managed correctly. Problems arise if a urethral injury is unrecognized and the urethra is further damaged by attempts at blind catheterization. In those instances, future reconstruction may be compromised and recurrent stricture rates rise. When managed well, these men have an excellent chance of becoming totally rehabilitated from a urinary standpoint.

Continence rates approach 100% in all series, particularly if the bladder neck is not involved. Potency status is probably related to the extent of the injury itself rather than the management of the problem. Several series have demonstrated only a small group of men losing erectile capabilities following the urethroplasty when they are potent following the actual injury 20.

The main complication following reconstruction of posterior injuries is recurrent stricture. When managed with standard urethroplasty techniques, recurrent stricture requiring major repeat operation should be observed in only 1%-2% of patients, although 10%-15% may require either dilation or incision of a short recurrence 21.

Endoscopic realignment by experienced physicians appears to produce similar results. When performed at 5-7 days postinjury, rare infectious complications occur despite the presence of the organized pelvic hematoma.

Complications of reconstruction of anterior urethral injuries are similar to those observed in posterior urethral repairs.

References- Doiron RC, Rourke KF. An overview of urethral injury. Can Urol Assoc J. 2019;13(6 Suppl4):S61–S66. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5931 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6565404

- Park S, McAninch JW. Straddle injuries to the bulbar urethra: Management and outcomes in 78 patients. J Urol. 2004;171:722–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000108894.09050.c0

- Bjurlin MA, Fantus RJ, Mellett MM, et al. Genitourinary injuries in pelvic fracture morbidity and mortality using the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma. 2009;67:1033–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bb8d6c

- Palminteri E, Berdondini E, Verze P, et al. Contemporary urethral stricture characteristics in the developed world. Urology. 2013;81:191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.08.062

- Chapple C, Barbagli G, Jordan G, et al. Consensus statement on urethral trauma. BJU Int. 2004;93:1195–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04805.x

- Morey AF, Brandes S, Dugi DD, 3rd, et al. Urotrauma: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2014;192:327–35. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.004

- Summerton DJ, Djakovic N, Kitrey ND, et al. Guidelines on urological trauma. https://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-trauma

- Andrich DE, Day AC, Mundy AR. Proposed mechanisms of lower urinary tract injury in fractures of the pelvic ring. BJU Int. Sept. 2007. 100:567-73.

- Siegel JA, Panda A, Tausch TJ, Meissner M, Klein A, Morey AF. Repeat Excision and Primary Anastomotic Urethroplasty for Salvage of Recurrent Bulbar Urethral Stricture. J Urol. 2015 Nov. 194 (5):1316-22.

- Reed A, Evans GH, Evans J, Kelley J, Ong D. Endoscopic Management of Penetrating Urethral Injury After an Animal Attack. J Endourol Case Rep. 2017. 3 (1):111-113.

- Bryk DJ, Zhao LC. Guideline of guidelines: a review of urological trauma guidelines. BJU Int. 2016 Feb. 117 (2):226-34.

- Mundy A, Andrich D. Urethral trauma. Part I: Introduction, history, anatomy, pathology, assessment, and emergency management. BJU Int. 2011;108:310–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10339.x

- Brandes S. Initial management of anterior and posterior urethral injuries. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.10.001

- Figler B, Hoffler CE, Reisman W, et al. Multidisciplinary update on pelvic fracture associated bladder and urethral injuries. Injury. 2012;43:1242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.03.031

- Kommu SS, Illahi I, Mumtaz F. Patterns of urethral injury and immediate management. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:383–9. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3282f0d5fd

- Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malagoni MA, et al. Organ injury scaling. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:293–303. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(16)46589-8

- Kielb SJ, Voeltz ZL, Wolf JS. Evaluation and management of traumatic posterior urethral disruption with flexible cystourethroscopy. J Trauma. 2001;50:36–40. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00006

- Koraitim MM. Effect of early realignment on length and delayed repair of post-pelvic fracture urethral injury. Urology. 2012;79:912–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.054

- Koraitim MM. Pelvic fracture urethral injuries: The unresolved controversy. J Urol. 1999;161:1433–41. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68918-5

- Tang CY, Fu Q, Cui RJ, Sun XJ. Erectile dysfunction in patients with traumatic urethral strictures treated with anastomotic urethroplasty: a single-factor analysis. Can J Urol. 2012 Dec. 19(6):6548-53.

- Odoemene CA, Okere P. One-stage Anastomotic Urethroplasty for Traumatic Urethral Strictures. January 2004-January 2013. Niger J Surg. 2015 Jul-Dec. 21 (2):124-9.