What is uterine prolapse

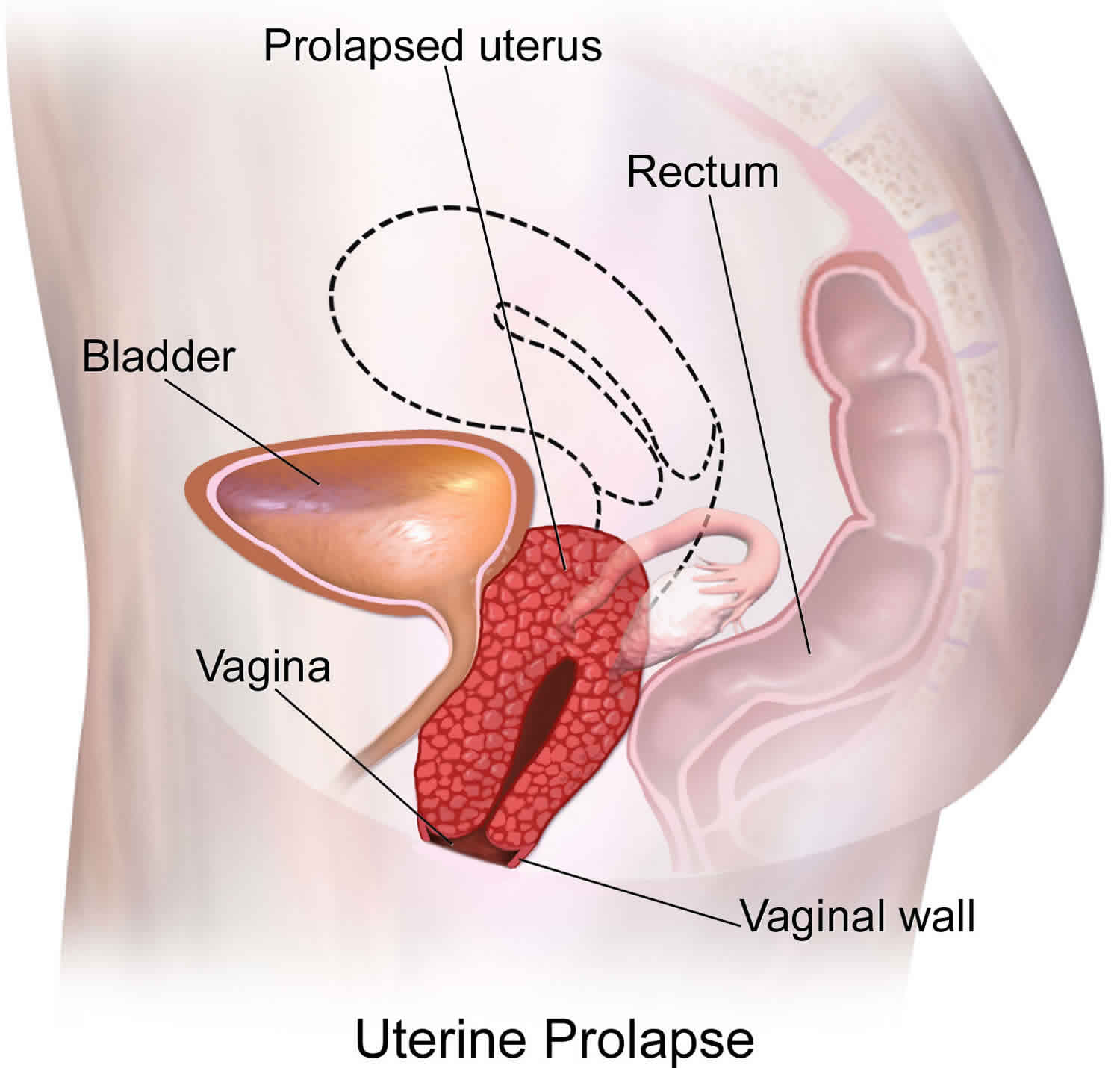

Uterine prolapse occurs when the womb (uterus) drops down and presses into the vaginal area. Uterine prolapse occurs when pelvic floor muscles and ligaments stretch and weaken and no longer provide enough support for the uterus. As a result, the uterus slips down into or protrudes out of the vagina.

Uterine prolapse can occur in women of any age. Prevalence increases with age. The prevalence of uterine prolapse increases with age until a peak of 5% in 60- to 69-year-old women 1. Some degree of prolapse is present in 41% to 50% of women on physical examination 2, but only 3% of patients report symptoms 1. Limited data suggest that prolapse progresses until menopause, with low rates of progression and regression thereafter 1. The number of women who have uterine prolapse is expected to increase by 46%, to 4.9 million, by 2050 3.

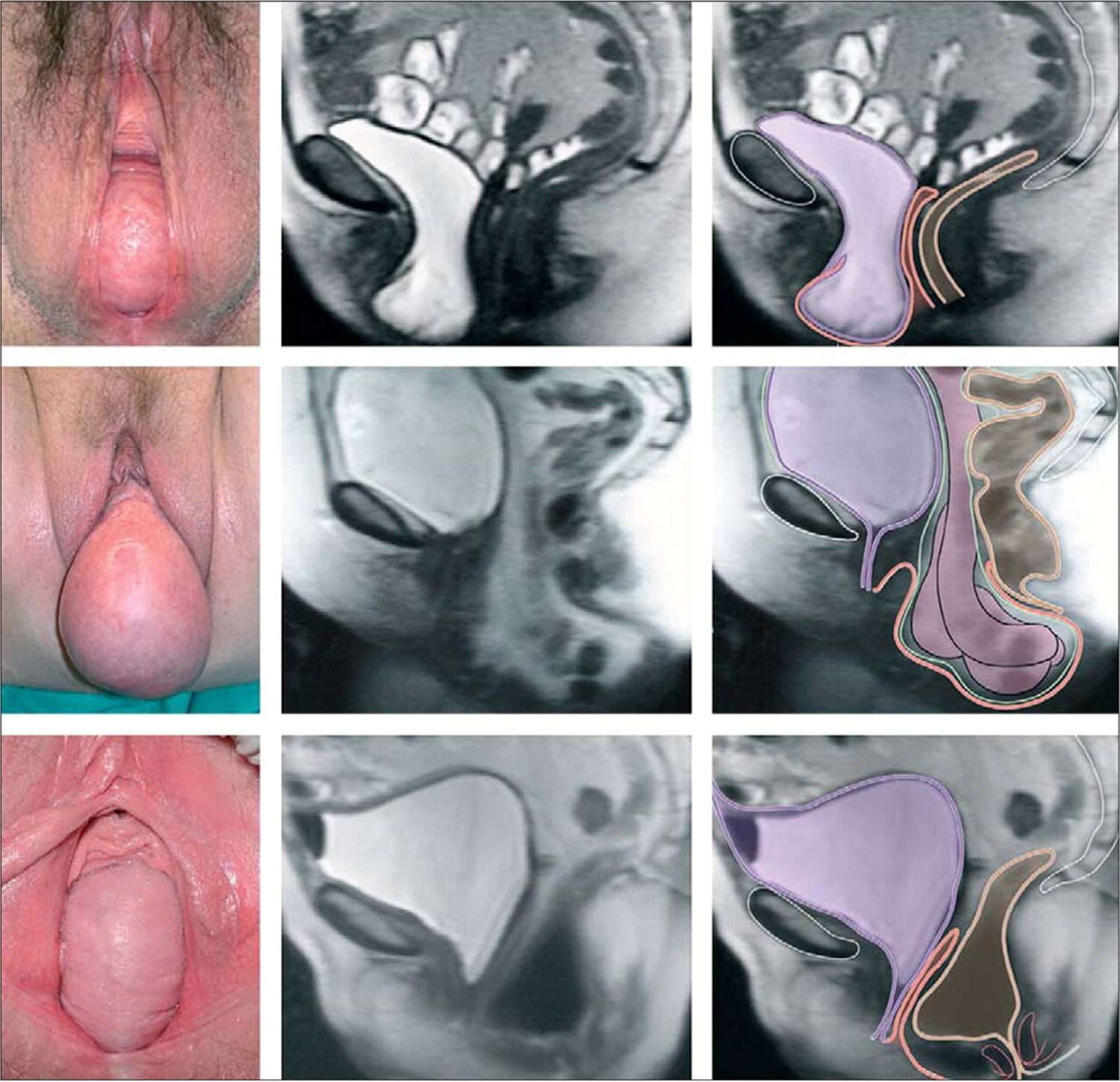

Current recommendations characterize the site of uterine prolapse as the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, and vaginal apex (apical prolapse). Apical prolapse is sometimes referred to as uterine or cervical prolapse when these structures are present; after total hysterectomy, prolapse of the vaginal cuff is referred to as vaginal vault prolapse (Figure 1). Anterior prolapse is two and three times more common than posterior and apical prolapse, respectively.

The cause of uterine prolapse is multifactorial but is primarily affects postmenopausal women who’ve had one or more vaginal deliveries, which lead to direct pelvic floor muscle and connective tissue injury 4. Hysterectomy, pelvic surgery, and conditions associated with sustained episodes of increased intra-abdominal pressure, including obesity, chronic cough, constipation, and repeated heavy lifting, also contribute to uterine prolapse. Most patients with mild uterine prolapse are asymptomatic and usually doesn’t require treatment. But if uterine prolapse makes you uncomfortable or disrupts your normal life, you might benefit from treatment. Symptoms become more bothersome as the bulge protrudes past the vaginal opening. Initial evaluation includes a history and systematic pelvic examination including assessment for urinary incontinence, bladder outlet obstruction, and fecal incontinence. Treatment options include observation, vaginal pessaries, and surgery. Most women can be successfully fit with a vaginal pessary. Available surgical options are reconstructive pelvic surgery with or without mesh augmentation and obliterative surgery.

Figure 1. Uterine prolapse

Footnote: Photographs in lithotomy position and sagittal magnetic resonance imaging showing vaginal-wall prolapse. Prolapse might include (top to bottom): anterior wall, vaginal apex, or posterior wall. Color codes include purple (bladder), orange (vagina), brown (colon and rectum), and green (peritoneum).

[Source 5 ]Uterine prolapse stages

Uterine prolapse can be categorized as incomplete or complete 6:

- Incomplete uterine prolapse: when an incomplete uterine prolapse occurs, the uterus is partially displaced into the vagina but does not protrude

- Complete uterine prolapse: when a complete uterine prolapse occurs, there is a portion of the uterus protruding out of the vaginal opening.

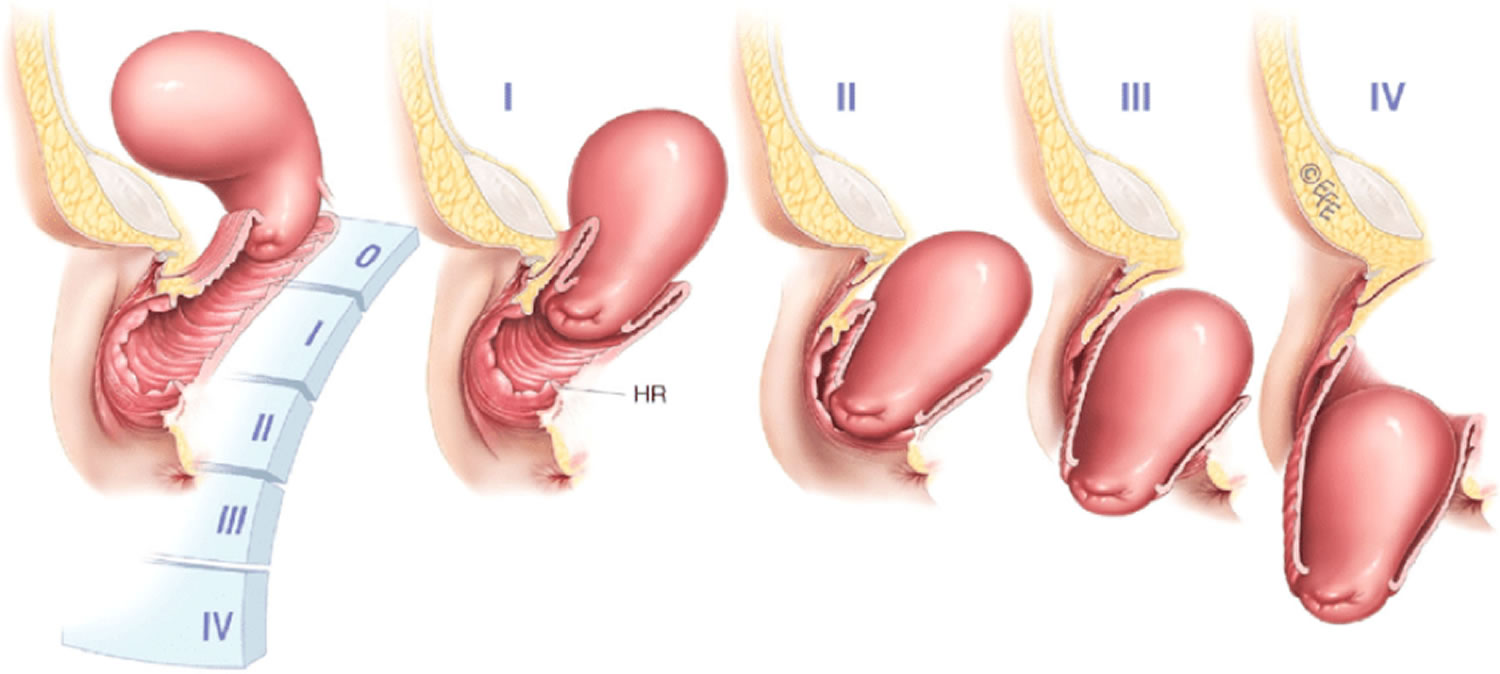

Uterine prolapse is graded by its severity, determined by how far the uterus has descended 7:

- Grade 1: the prolapsed uterus is more than 1 cm above the opening of the vagina.

- Grade 2: the prolapsed uterus is 1 cm or less from the opening of the vagina.

- Grade 3: the prolapsed uterus sticks out of the vagina opening more than 1 cm, but not fully.

- Grade 4: the full length of the prolapsed uterus bulges out of the vagina.

Figure 2. Uterine prolapse grading

Table 1. Uterine prolapse stages and grades

| Baden-Walker system | Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Description | Stage | Description |

| 0 | Normal position for each respective site, no prolapse | 0 | No prolapse |

| 1 | Descent halfway to the hymen | I | Greater than 1 cm above the hymen |

| 2 | Descent to the hymen | II | 1 cm or less proximal or distal to the plane of the hymen |

| 3 | Descent halfway past the hymen | III | Greater than 1 cm below the plane of the hymen, but protruding no farther than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length |

| 4 | Maximal possible descent for each site | IV | Eversion of the lower genital tract is complete |

Footnotes: *The Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system is an adaptation of the Baden–Walker halfway system 8. Since 1996, the POPQ has been internationally recognised as a standard classification system for genital prolapse. The POPQ is more accurate than the Baden–Walker system because it measures, in centimetres, the positions of 9 sites of the vagina and the perineal body in relation to the hymen, to create a tandem vaginal profile before assigning site specific ordinal stages. The main limitation of the POPQ system is that it is more complex to learn and communicate verbally than the original Baden–Walker system. †Both systems measure the position of the most distal portion of the prolapse site during the Valsalva maneuver.

[Source 9 ]Uterine prolapse causes

The cause of uterine prolapse is multifactorial, but pregnancy is the most commonly associated risk factor. Uterine prolapse results from the weakening of pelvic muscles and supportive tissues. Causes of weakened pelvic muscles and tissues include:

- Pregnancy

- Difficult labor and delivery or trauma during childbirth

- Delivery of a large baby

- Being overweight or obese

- Lower estrogen level after menopause

- Chronic constipation or straining with bowel movements

- Chronic cough or bronchitis

- Repeated heavy lifting

Normal pelvic support is primarily provided by the levator ani muscles and the connective tissue attachments of the vagina to the sidewalls and pelvis. With normal pelvic support, the vagina lies horizontally atop the levator ani muscles. When damaged, the levator ani muscles become more vertical in orientation and the vaginal opening widens, shifting support to the connective tissue attachments. Biomechanical modeling has demonstrated that during the second stage of labor, levator ani muscles are stretched more than 200% beyond the threshold for stretch injuries 10.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of parous women revealed that those with prolapse within 1 cm of the hymen are 7.3 times more likely to have levator ani injuries than women without prolapse 11. Prospective ultrasound studies of initially nulliparous women revealed that the prevalence of levator ani injuries is 21% to 36% after vaginal delivery 12 and that these injuries correlate with prolapse symptoms 12. Of note, 17% of nulliparous women with prolapse have levator ani injuries visible on magnetic resonance imaging 13.

Risk factors for uterine prolapse

Factors that can increase your risk of uterine prolapse include:

- One or more pregnancies and vaginal births

- Giving birth to a large baby

- Increasing age 14

- Obesity

- Prior pelvic surgery

- Chronic constipation or frequent straining during bowel movements

- Family history of weakness in connective tissue 14

- Being Hispanic or white 15

- Connective tissue disorders (e.g., Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) 14

- Chronic cough

- Constipation,

- Repeated heavy lifting 14

- Hysterectomy/previous prolapse surgery 14

Elevated body mass index (BMI) is a risk factor for uterine prolapse. In one study, women who were obese were more likely to have progression of prolapse by 1 cm or more in one year 16. Weight loss does not reverse herniation 17.

Uterine prolapse prevention

To reduce your risk of uterine prolapse, try to:

- Perform Kegel exercises regularly. These exercises can strengthen your pelvic floor muscles — especially important after you have a baby.

- Treat and prevent constipation. Drink plenty of fluids and eat high-fiber foods, such as fruits, vegetables, beans and whole-grain cereals.

- Avoid heavy lifting and lift correctly. When lifting, use your legs instead of your waist or back.

- Control coughing. Get treatment for a chronic cough or bronchitis, and don’t smoke.

- Avoid weight gain. Talk with your doctor to determine your ideal weight and get advice on weight-loss strategies, if you need them.

Uterine prolapse signs and symptoms

Mild uterine prolapse generally doesn’t cause signs or symptoms.

Signs and symptoms of moderate to severe uterine prolapse include:

- Sensation of heaviness, pressure or pulling in your pelvis or vagina

- Tissue protruding from your vagina

- Urinary problems, such as urine leakage (incontinence) or urine retention

- Trouble having a bowel movement

- Feeling as if you’re sitting on a small ball or as if something is falling out of your vagina

- Problems with sexual intercourse, such as a sensation of looseness in the tone of your vaginal tissue

- Low backache

- Uterus and cervix that bulge into the vaginal opening

- Repeated bladder infections

- Vaginal bleeding

- Increased vaginal discharge

Often, symptoms are less bothersome in the morning and worsen as the day goes on.

Seeing or feeling a bulge that protrudes to or past the vaginal opening is the most specific symptom 18. During a well-woman visit, questions such as “Do you see or feel a bulge in your vagina?” can provide screening for uterine prolapse 2.

Uterine prolapse often coexists with other pelvic floor disorders. Of those with prolapse, 40% have stress urinary incontinence, 37% have overactive bladder, and 50% have fecal incontinence. Patients who report experiencing any of these disorders should be evaluated for the others as well 19.

Bladder outlet obstruction may occur because of urethral kinking or pressure on the urethra. Uterine prolapse symptoms may not correlate with the location or severity of the prolapsed compartment 20. Patients with posterior vaginal prolapse sometimes use manual pressure on the perineum or posterior vagina (called splinting) to help complete evacuation of stool. Uterine prolapse may negatively affect sexual activity, body image, and quality of life 21. Physicians must ask specific questions about pelvic floor disorders because patients often do not volunteer this information out of feelings of embarrassment and shame 22.

See your doctor to discuss your options if signs and symptoms of uterine prolapse become bothersome and disrupt your normal activities.

Uterine prolapse complications

Severe uterine prolapse can displace part of the vaginal lining, causing it to protrude outside the body. Vaginal tissue that rubs against clothing can lead to vaginal sores (ulcers.) Rarely, the sores can become infected.

Uterine prolapse is often associated with prolapse of other pelvic organs. You might experience:

- Anterior prolapse (cystocele). Weakness of connective tissue separating the bladder and vagina may cause the bladder to bulge into the vagina. Anterior prolapse is also called prolapsed bladder.

- Posterior vaginal prolapse (rectocele). Weakness of connective tissue separating the rectum and vagina may cause the rectum to bulge into the vagina. You might have difficulty having bowel movements.

- Constipation and hemorrhoids may occur because of a rectocele.

Severe uterine prolapse can displace part of the vaginal lining, causing it to protrude outside the body. Vaginal tissue that rubs against clothing can lead to vaginal sores (ulcers.) Rarely, the sores can become infected.

Uterine prolapse diagnosis

A diagnosis of uterine prolapse generally occurs during a pelvic exam. Uterine prolapse is dynamic, and symptoms and examination findings may vary day to day, or within a day depending on the level of activity and the fullness of the bladder and rectum. Standing, lifting, coughing, and physical exertion, although not causal factors, may increase bulging and discomfort. Patients with complete uterine prolapse (i.e., procidentia) may have vaginal discharge related to chafing or epithelial erosion.

During the pelvic exam your doctor is likely to ask you:

- To bear down as if having a bowel movement. Bearing down can help your doctor assess how far the uterus has slipped into the vagina.

- To tighten your pelvic muscles as if you’re stopping a stream of urine. This test checks the strength of your pelvic muscles.

When uterine prolapse is suspected, a pelvic examination is required to fully characterize the location and extent of uterine prolapse. First, the vaginal opening and perineal body are observed while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. A speculum is then inserted to visualize the vaginal apex (cervix or vaginal cuff), and vaginal length noted. The Valsalva maneuver is again performed and the speculum is slowly removed to observe apical descent. Next, the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are examined while the opposite wall is retracted using a one-blade speculum (e.g., Sims speculum). Measurements may be taken, and, using the pelvic organ prolapse quantification staging system or the Baden-Walker grading system, the extent of the prolapse classified. Finally, assessment for infection, hematuria, and incomplete bladder emptying is necessary. A urine dipstick analysis and postvoid residual volume test, using either a voided specimen with bladder scanner or in-and-out catheter insertion, are appropriate for this purpose.

A rectal examination should be performed to assess sphincter tone. If no bulge is noted, or if the observed bulge does not correlate with the patient’s symptoms, the patient should also be examined in the standing, straining position.

You might fill out a questionnaire that helps your doctor assess how uterine prolapse affects your quality of life. This information helps guide treatment decisions.

If you have severe incontinence, your doctor might recommend tests to measure how well your bladder functions (urodynamic testing).

Further Evaluation

The need for additional evaluation depends on patient symptoms, stage of uterine prolapse, and the proposed treatment plan. Up to one-half of women who undergo prolapse surgery may experience de novo stress urinary incontinence caused by urethral unkinking 23. Complex urodynamic testing performed while reducing the prolapse with swabs or a speculum may help predict which women will benefit from a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure 24. In cases of recurrent or unusual prolapse (e.g., large perineal bulge), defecation proctography or dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging may be useful.

Uterine prolapse treatment

Treatment depends on the severity of uterine prolapse. The primary goal of any treatment is to improve symptoms and, for conservative management, to minimize prolapse progression. The choice of treatment is driven by patient preferences; however, patients with symptomatic prolapse should be made aware that pessary use is a viable nonsurgical option 25. Your doctor might recommend:

- Self-care measures. If your uterine prolapse causes few or no symptoms, simple self-care measures may provide relief or help prevent worsening prolapse. Self-care measures include performing Kegel exercises to strengthen your pelvic muscles, losing weight and treating constipation.

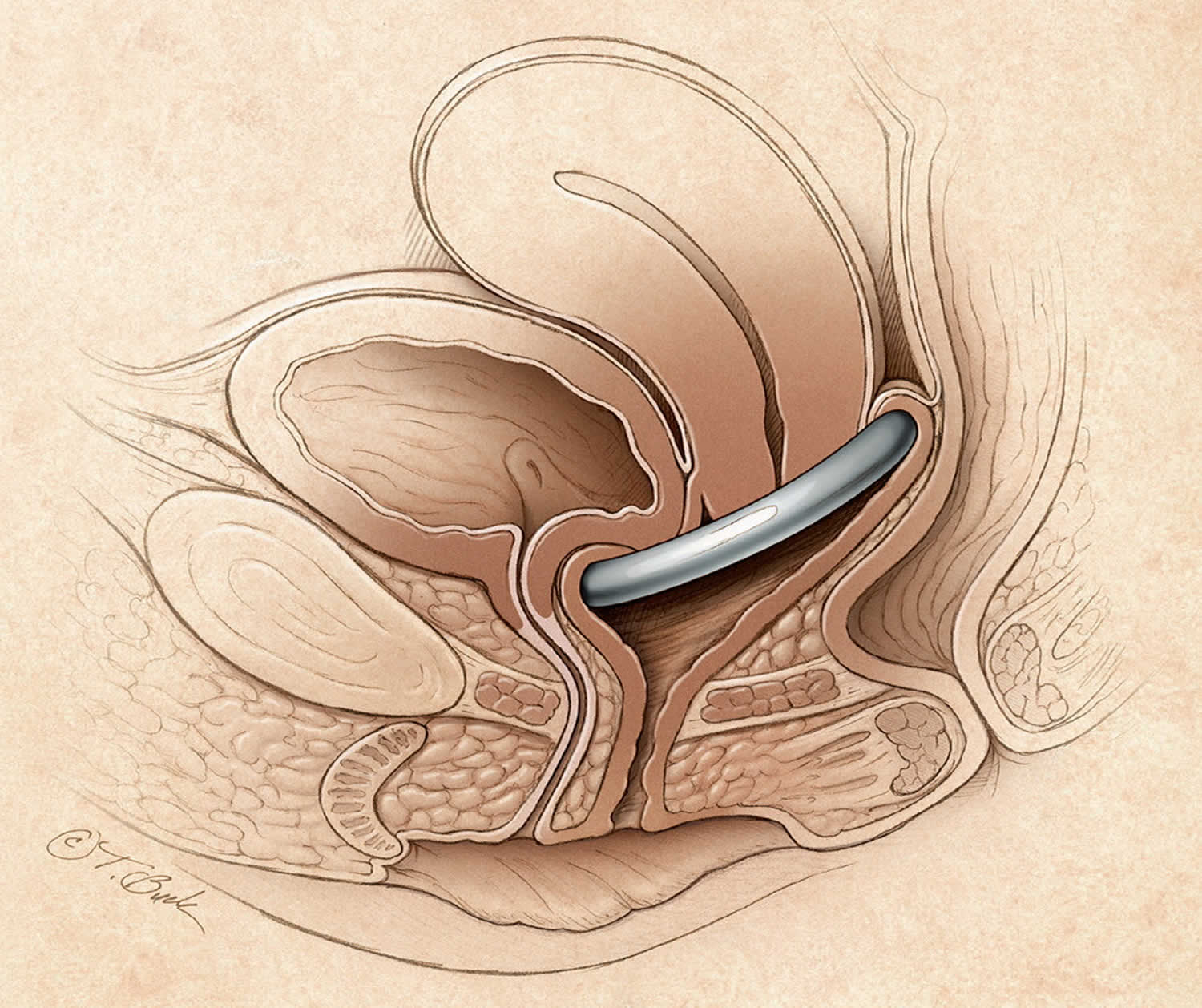

- Pessary. A vaginal pessary is a plastic or rubber ring inserted into your vagina to support the bulging tissues. A pessary must be removed regularly for cleaning.

Most cases of uterine prolapse do not require treatment; however, women with prolapse beyond the vaginal opening typically desire some intervention. Contraindications to expectant management are: (1) hydroureteronephrosis resulting from ureteral kinking with descent of the bladder, (2) recurrent urinary tract infections or ureteral reflux due to bladder outlet obstruction, and (3) severe vaginal or cervical erosions and infections. Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation and avoidance of heavy lifting and constipation may reduce symptoms.

Hormone (estrogen) treatment

If you have a mild uterine prolapse and have been through the menopause, your doctor may recommend treatment with the hormone oestrogen to ease some of your symptoms, such as vaginal dryness or discomfort during sex.

Estrogen is available as:

- a cream you apply to your vagina

- a tablet you insert into your vagina

Vaginal pessary

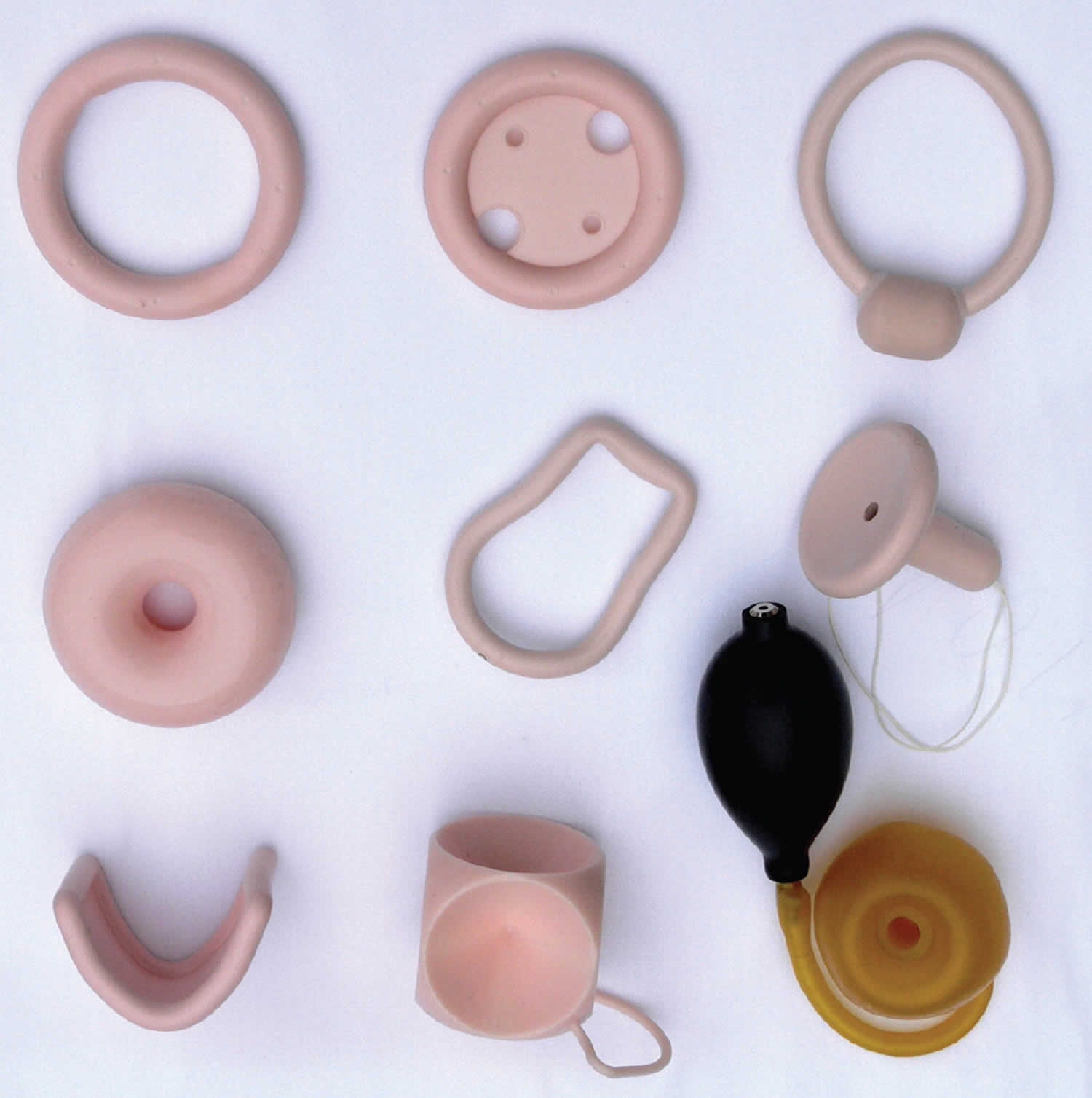

Pessaries are devices that are placed in the vagina to restore normal pelvic anatomy and decrease prolapse symptoms (Figure 2). They are primarily made from medical-grade silicone. Two-thirds of patients with pelvic organ prolapse initially choose management with a pessary 26 and up to 77% will continue pessary use after one year 27. Pessaries are an option for all stages of prolapse, and they may prevent progression of prolapse and avert or delay the need for surgery 28. Additionally, continence pessaries have a knob to coapt the urethra for treatment of stress incontinence.

Use of a vaginal pessary may be limited in patients with dementia or pelvic pain. Women with decreased dexterity may require office management of pessaries. These devices should not be placed in patients who are unlikely to adhere to instructions for care or follow-up because serious complications such as erosion into the bladder or rectum can result from pessary neglect.

Pessary Selection. Pessaries may be supportive or space occupying. The ring pessary, a supportive device, is the most commonly used pessary in the United States, followed by the space-occupying Gellhorn and donut pessaries (Figure 3) 29. More advanced prolapse often requires space-occupying devices 30. However, the PESSRI trial, the only randomized controlled trial comparing pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse, reported no difference in patient symptoms between the ring and Gellhorn pessaries 31. Support pessaries can be inserted and removed by the patient, may allow for sexual intercourse, and are associated with less vaginal discharge and irritation compared with space-occupying pessaries 32.

Table 2. A simplified approach to Pessary Selection

| Trial | Pessary type |

|---|---|

| 1 | Ring with support |

| Ring with support and knob, if urinary incontinence is present | |

| 2 | Gellhorn |

| 3 | Donut |

| 4 | Combination of pessaries: ring plus Gellhorn, ring plus donut, or two donuts; use ring with support and knob, if urinary incontinence is present |

| 5 | Cube or Inflatoball |

Footnote: Fitting is successful if the pessary is not expelled with cough or Valsalva maneuver and if the patient is not aware of having the pessary in place during ambulation, voiding, sitting, and defecation.

[Source 33 ]Figure 3. Vaginal pessary

Figure 4. Vaginal pessary types

Footnote: Some common pessaries. First row (left to right): ring, ring with support, and incontinence ring; second row: donut, Smith-Hodge, and Gellhorn; third row: Gehrung, cube, and Inflatoball.

[Source 34 ]Pessary Fitting

More than 85% of patients who choose treatment with a pessary are successfully fit with one 35. Short vaginal length, wide vaginal opening (greater than four fingerbreadths), and history of hysterectomy are risk factors for fitting failure 30. Fitting is performed through trial and error. Most physicians initially try a ring pessary. A ring pessary is folded in half for insertion and should fit between the pubic symphysis and posterior vaginal fornix. The pessary should remain more than one fingerbreadth above the introitus when the patient bears down. The patient should walk, sit, and void with the pessary in place to assess comfort and retention. Once the appropriate fit is obtained, instructions on insertion and nightly removal and cleaning should be provided to the patient. Less frequent removal at weekly, biweekly, or monthly intervals is also acceptable.

Follow-up

Patients should return one to two weeks after their pessary fitting to assess satisfaction with the device and symptom improvement. Thereafter, women who perform self-care may return annually for examination. Other women should generally return every three months for pessary removal, cleaning, and examination.

Side effects of vaginal pessaries

Vaginal pessaries can occasionally cause:

- unpleasant smelling vaginal discharge, which could be a sign of an imbalance of the usual bacteria found in your vagina (bacterial vaginosis)

- some irritation and sores inside your vagina, and possibly bleeding

- stress incontinence, where you pass a small amount of urine when you cough, sneeze or exercise

- a urinary tract infection

- interference with sex – but most women can have sex without any problems

These side effects can usually be treated.

The most common complications of pessary use are vaginal discharge, irritation, ulceration, bleeding, pain, and odor. Bacterial vaginosis occurs in up to 30% of patients who have a pessary and is more common with less frequent pessary removal 36. Vaginal ulceration and bleeding occur more commonly in postmenopausal women and with less frequent pessary removal; vaginal estrogen therapy is commonly prescribed for treatment and prevention of vaginal ulceration and irritation. A recent randomized controlled trial of hydroxyquinoline-based gel (Trimosan gel) for prevention of bacterial vaginosis found that a higher proportion of women using hormone therapy had vaginal sores 36. Additionally, a retrospective cohort study found that vaginal estrogen therapy was not protective against vaginal ulcerations or bleeding 37. Women with vaginal bleeding and an intact uterus and no obvious ulceration require further evaluation for endometrial pathology.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Depending on the severity of your uterine prolapse, self-care measures may provide relief. Try to:

- Perform Kegel exercises to strengthen pelvic muscles and support the weakened fascia

- Avoid constipation by eating high-fiber foods and drinking plenty of fluids

- Avoid bearing down to move your bowels

- Avoid heavy lifting

- Control coughing

- Lose weight if you’re overweight or obese

Kegel exercises

Kegel exercises strengthen your pelvic floor muscles. A strong pelvic floor provides better support for your pelvic organs, prevents prolapse from worsening and relieves symptoms associated with uterine prolapse.

To perform Kegel exercises:

- Begin by emptying your bladder.

- Tighten (contract) your pelvic floor muscles as though you were trying to prevent passing gas.

- Hold the contraction for five seconds, and then relax for five seconds. If this is too difficult, start by holding for two seconds and relaxing for three seconds.

- Work up to holding the contractions for 10 seconds at a time.

- Aim for at least three sets of 10 repetitions each day (morning, afternoon, and night).

Because these muscles control the bladder, rectum, and vagina, the following tips may help:

- Insert a finger into your vagina. Tighten the muscles as if you are holding in your urine, then let go. You should feel the muscles tighten and move up and down.

It is very important that you keep the following muscles relaxed while doing pelvic floor muscle training exercises:

- Abdominal

- Buttocks (the deeper, anal sphincter muscle should contract)

- Thigh

Kegel exercises may be most successful when they’re taught by a physical therapist and reinforced with biofeedback. Biofeedback involves using monitoring devices that help ensure you’re tightening the muscles properly for the best length of time.

A pelvic floor muscle training exercise is like pretending that you have to urinate, and then holding it. You relax and tighten the muscles that control urine flow. It is important to find the right muscles to tighten.

The next time you have to urinate, start to go and then stop. Feel the muscles in your vagina, bladder, or anus get tight and move up. These are the pelvic floor muscles. If you feel them tighten, you have done the exercise right.

You can do these exercises at any time and place. Most people prefer to do the exercises while lying down or sitting in a chair. After 4 to 6 weeks, most people notice some improvement. It may take as long as 3 months to see a major change.

After a couple of weeks, you can also try doing a single pelvic floor contraction at times when you are likely to leak (for example, while getting out of a chair).

A word of caution: Some people feel that they can speed up the progress by increasing the number of repetitions and the frequency of exercises. However, over-exercising can instead cause muscle fatigue and increase urine leakage.

If you feel any discomfort in your abdomen or back while doing these exercises, you are probably doing them wrong. Breathe deeply and relax your body when you do these exercises. Make sure you are not tightening your stomach, thigh, buttock, or chest muscles.

When done the right way, pelvic floor muscle exercises have been shown to be very effective at improving urinary continence.

If you are still not sure whether you are tightening the right muscles, keep in mind that all of the muscles of the pelvic floor relax and contract at the same time.

A woman can also strengthen these muscles by using a vaginal cone, which is a weighted device that is inserted into the vagina. Then you try to tighten the pelvic floor muscles to hold the device in place.

Kegel exercises may be most successful when they’re taught by a physical therapist and reinforced with biofeedback. If you are unsure whether you are doing the pelvic floor muscle training correctly, you can use biofeedback and electrical stimulation to help find the correct muscle group to work.

- Biofeedback is a method of positive reinforcement. Electrodes are placed on the abdomen and along the anal area. Some therapists place a sensor in the vagina in women or anus in men to monitor the contraction of pelvic floor muscles.

- A monitor will display a graph showing which muscles are contracting and which are at rest. The therapist can help find the right muscles for performing pelvic floor muscle training exercises.

There are physical therapists specially trained in pelvic floor muscle training. Many people benefit from formal physical therapy.

Uterine prolapse surgery

Your doctor might recommend surgery to repair uterine prolapse. Minimally invasive (laparoscopic) or vaginal surgery might be an option. Obliterative and reconstructive surgeries for uterine prolapse are available and may include hysterectomy or uterine conservation (hysteropexy). The decision for surgery must include a discussion of a patient’s goals and expectations based on cultural views such as body image and desire for future sexual function, including vaginal intercourse 38.

Surgery can involve:

- Repair of weakened pelvic floor tissues. This surgery is generally approached through the vagina but sometimes through the abdomen. The surgeon might graft your own tissue, donor tissue or a synthetic material onto weakened pelvic floor structures to support your pelvic organs.

- Removal of your uterus (hysterectomy). Hysterectomy might be recommended for uterine prolapse in certain instances. A hysterectomy is generally very safe, but with any surgery comes the risk of complications.

- Closing the vagina (colpocleisis). Occasionally, an operation that closes part or all the vagina (colpocleisis) may be an option. This treatment is only offered to women who have advanced prolapse, when other treatments haven’t worked and they are sure they don’t plan on having sexual intercourse again in the future. This operation can be a good option for frail women who wouldn’t be able to have more complex surgery.

Vaginal obliteration (colpocleisis) has the highest cure rate and lowest morbidity of any surgical intervention and is an excellent option for women who do not desire any future vaginal intercourse. For women who prefer to maintain coital function, reconstructive surgery should be performed and the vaginal apex can be suspended using the woman’s own tissues and sutures (native tissue repair), or mesh can be placed abdominally, to suspend the top of the vagina to the sacrum (sacrocolpopexy), or transvaginally (transvaginal mesh).

Use of vaginal mesh

Surgical repair for pelvic organ prolapse may not always be successful, and the prolapse can return.

For this reason, synthetic (non-absorbable) and biological (absorbable) meshes were introduced to support the vaginal wall and/or internal organs.

Most women treated with mesh respond well to this treatment. But the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have received reports of complications associated with meshes. These include:

- long-lasting pain

- incontinence

- constipation

- sexual problems

- mesh exposure through vaginal tissues and occasionally injury to nearby organs, such as the bladder or bowel

Transvaginal mesh prolapse repairs have been intensely scrutinized. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an advisory recommending that physicians discuss potential complications of vaginal mesh for prolapse with patients 39. It is important to note that synthetic mesh for suburethral slings and sacrocolpopexy is not included in the advisory. The American Urogynecologic Society and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a joint statement in 2011 40 in which they agreed that use of transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse should be reserved for complex patients, such as those with advanced or recurrent prolapse or medical conditions that make more invasive and lengthier open or endoscopic procedures too risky. The Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry (https://www.augs.org/clinical-practice/pfd-research-registry/), created by the American Urogynecologic Society for the purpose of surveillance of transvaginal mesh implants, also collects validated objective outcome measures and electronic patient-reported outcomes.

Talk with your doctor about all your treatment options to be sure you understand the risks and benefits of each so that you can choose what’s best for you.

Since July 11 2018, this type of operation has been paused in the UK while extra safety measures are put in place.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that mesh should only be used for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse under research circumstances. If you join a research study, NICE recommends that you’re regularly monitored for any complications.

If you’re thinking about having vaginal mesh inserted, you may want to ask your surgeon some of these questions before you proceed:

- what are the alternatives?

- what are the chances of success with the use of mesh versus use of other procedures?

- what are the pros and cons of using mesh, and what are the pros and cons of alternative procedures?

- what experience have you had with implanting mesh?

- how successful has it been for the people you have treated?

- what has been your experience in dealing with any complications?

- what if the mesh doesn’t correct my problems?

- if I have a complication related to the mesh, can it be removed and what are the consequences associated with this?

- what happens to the mesh over time?

Side effects of surgery

Your surgeon will explain the risks of your surgery in more detail, but possible side effects could include:

- risks associated with anaesthesia

- bleeding, which may require a blood transfusion

- damage to the surrounding organs, such as your bladder or bowel

- an infection – you may be given antibiotics to take during and after surgery to reduce the risk

- changes to your sex life, such as discomfort during intercourse – but this should improve over time

- vaginal discharge and bleeding

- experiencing more prolapse symptoms, which may require further surgery

- a blood clot forming in one of your veins, such as in your leg – you may be given medication to help reduce this risk after surgery (see deep vein thrombosis or DVT for more information)

If you experience any of the following symptoms after your surgery, let your surgeon or doctor know as soon as possible:

- a high temperature (fever) of 100.4 °F (38 °C) or more

- severe pain low in your tummy

- heavy vaginal bleeding

- a stinging or burning sensation when you pass urine

- abnormal vaginal discharge – this may be an infection

Recovering from surgery

You will probably need to stay in hospital overnight or for a few days following surgery.

You may have a drip in your arm to provide fluids, and a thin plastic tube (catheter) to drain urine from your bladder. Some gauze may be placed inside your vagina to act as a bandage for the first 24 hours, which may be slightly uncomfortable.

For the first few days or weeks after your operation, you may have some vaginal bleeding similar to a period, as well as some vaginal discharge. This may last 3 or 4 weeks. During this time, you should use sanitary towels rather than tampons.

Your stitches will usually dissolve on their own after a few weeks.

You should try to move around as soon as possible but with good rests every few hours.

You should be able to have a shower and bathe as normal once you’ve left hospital, but you may need to avoid swimming for a few weeks.

It’s best to avoid having sex for around 4 to 6 weeks, until you’ve healed completely.

Your care team will advise about when you can return to work.

References- Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, et al. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):141–148.

- Barber MD, Maher C. Epidemiology and outcome assessment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(11):1783–1790.

- Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1027–1038.

- Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Aug 1;96(3):179-185. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0801/p179.html

- Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet . 2007;369(9566):1028.

- The Causes, Symptoms and Treatment of Uterine Prolapse. FLEUR Womens Health. http://www.fleurhealth.com/blog/the-causes-symptoms-and-treatment-of-uterine-prolapse/

- Pelvic Organ Prolapse. http://www.gynaecologyspecialistlondon.co.uk/conditions-treatments/pelvic-organ-prolapse/

- Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, Shull BL, Smith AR. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Jul;175(1):10-7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0

- Onwude JL. Genital prolapse in women. BMJ Clin Evid. 2012 Mar 14;2012:0817. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3635656

- Lien KC, Mooney B, DeLancey JO, Ashton-Miller JA. Levator ani muscle stretch induced by simulated vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):31–40.

- DeLancey JO, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, et al. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 pt 1):295–302.

- van Delft K, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Schwertner-Tiepelmann N, Kluivers K. The relationship between postpartum levator ani muscle avulsion and signs and symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction. BJOG. 2014;121(9):1164–1171.

- DeLancey JO, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, et al. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 pt 1):295–302

- Vergeldt TF, Weemhoff M, IntHout J, Kluivers KB. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and its recurrence: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2105;26(11):1559–1573.

- Whitcomb EL, Rortveit G, Brown JS, et al. Racial differences in pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1271–1277.

- Bradley CS, Zimmerman MB, Qi Y, Nygaard IE. Natural history of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):848–854.

- Kudish BI, Iglesia CB, Sokol RJ, et al. Effect of weight change on natural history of pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):81–88.

- Barber MD, Neubauer NL, Klein-Olarte V. Can we screen for pelvic organ prolapse without a physical examination in epidemiologic studies? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(4):942–948.

- Lawrence JM, Lukacz ES, Nager CW, Hsu JW, Luber KM. Prevalence and co-occurrence of pelvic floor disorders in community-dwelling women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):678–685.

- Miedel A, Tegerstedt G, Maehle-Schmidt M, Nyrén O, Hammarström M. Symptoms and pelvic support defects in specific compartments. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):851–858.

- Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1455–1461.

- Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al.; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311–1316.

- Wei JT, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al.; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. A midurethral sling to reduce incontinence after vaginal prolapse repair. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2358–2367.

- Visco AG, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al.; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. The role of preoperative urodynamic testing in stress-continent women undergoing sacrocolpopexy: the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) randomized surgical trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):607–614.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology and the American Urogynecoligc Society. Practice bulletin no. 176: pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(4):e56–e72.

- Kapoor DS, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Oliver R. Conservative versus surgical management of prolapse: what dictates patient choice? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(10):1157–1161.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Sokol ER, Jackson ND, Myers DL. Patient characteristics that are associated with continued pessary use versus surgery after 1 year. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):159–164.

- Handa VL, Jones M. Do pessaries prevent the progression of pelvic organ prolapse? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002;13(6):349–351.

- Kuncharapu I, Majeroni BA, Johnson DW. Pelvic organ prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(9):1111–1117.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, Jackson ND, Myers DL. Risk factors associated with an unsuccessful pessary fitting trial in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):345–350.

- Cundiff GW, Amundsen CL, Bent AE, et al. The PESSRI study: symptom relief outcomes of a randomized crossover trial of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):405.e1–405.e8.

- Rogers RG. Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery: Clinical Practice and Surgical Atlas. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill Education/Medical; 2013.

- Kuncharapu I, Majeroni BA, Johnson DW. Pelvic organ prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(9):1116.

- Kuncharapu I, Majeroni BA, Johnson DW. Pelvic organ prolapse. Am Fam Physician . 2010;81(9):1114.

- Lamers BH, Broekman BM, Milani AL. Pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse and health-related quality of life: a review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(6):637–644.

- Meriwether KV, Rogers RG, Craig E, Peterson SD, Gutman RE, Iglesia CB. The effect of hydroxyquinoline-based gel on pessary-associated bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(5):729.e1–729.e9.

- Dessie SG, Armstrong K, Modest AM, Hacker MR, Hota LS. Effect of vaginal estrogen on pessary use [published correction appears in Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(9):1431]. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(9):1423–1429.

- Handa VL, Cundiff G, Chang HH, Helzlsouer KJ. Female sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(5):1045–1052.

- Urogynecologic Surgical Mesh Implants. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/implants-and-prosthetics/urogynecologic-surgical-mesh-implants

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion no. 513: vaginal placement of synthetic mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(6):1459–1464.