Ventricular fibrillation

Ventricular fibrillation or v-fib, is a life-threatening and a medical emergency heart rhythm disturbance. Ventricular fibrillation occurs if disorganized electrical signals make the ventricles (the heart’s lower chambers) quiver or fibrillate, instead of contracting (or beating) normally. Without the ventricles pumping blood to the body, the person collapse (syncope) within seconds, sudden cardiac arrest and death can occur within a few minutes. Ventricular fibrillation is an emergency that requires immediate medical attention, and is the most frequent cause of sudden cardiac death. Ventricular fibrillation must be treated immediately with defibrillation, which delivers an electrical shock to the heart and restores normal heart rhythm. Emergency treatment includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and shocks to the heart with a device called an automated external defibrillator (AED). The rate of long-term complications and death is directly related to the speed with which you receive defibrillation.

Treatments to prevent sudden cardiac death for those at risk of ventricular fibrillation include medications and implantable devices that can restore a normal heart rhythm.

Your heart pumps blood to the lungs, brain, and other organs. If the heartbeat is interrupted, even for a few seconds, it can lead to fainting (syncope) or cardiac arrest. Sometimes triggered by a heart attack, ventricular fibrillation causes your blood pressure to plummet, cutting off blood supply to your vital organs. Sudden cardiac death results.

What’s a normal heartbeat?

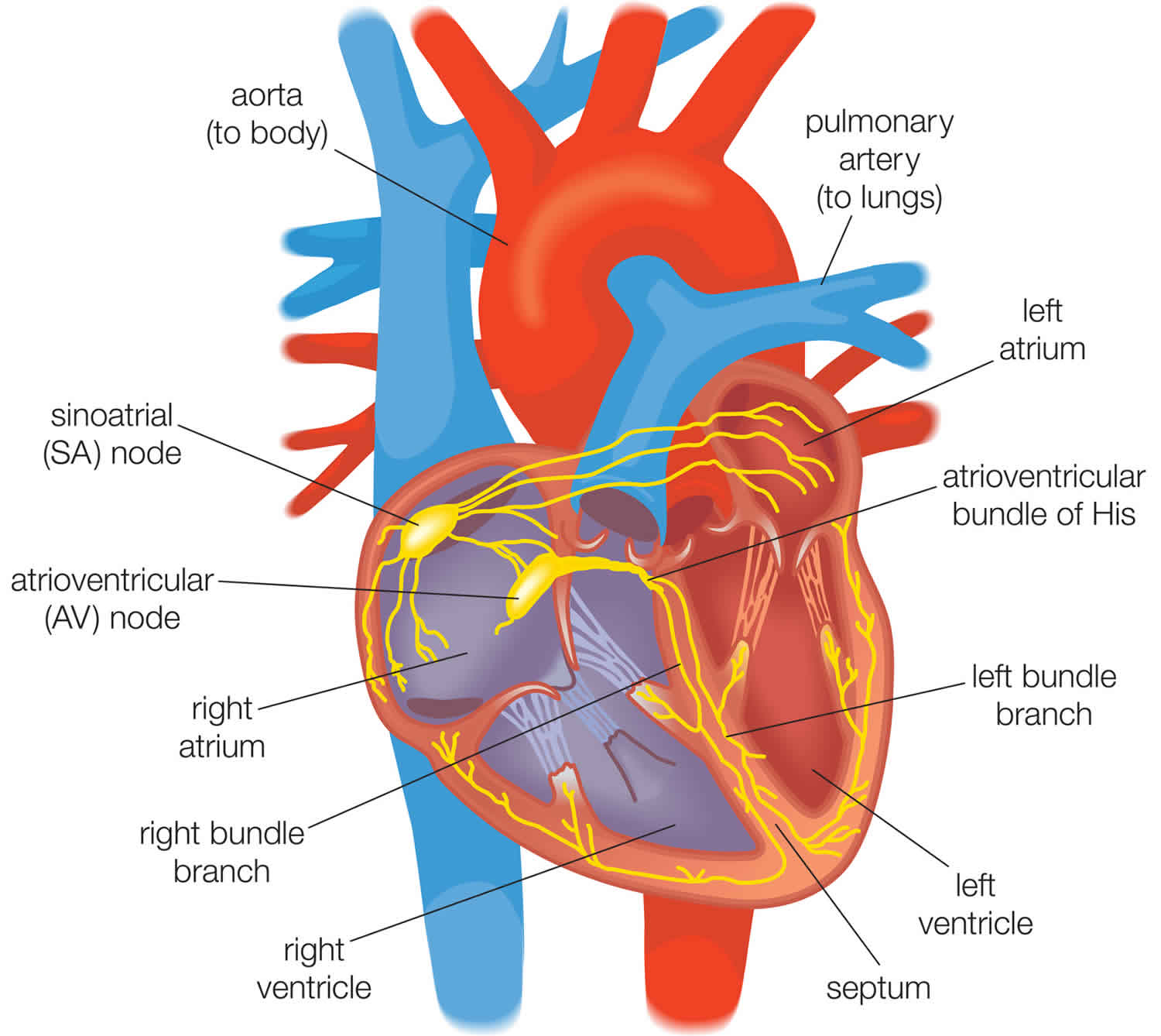

When your heart beats, the electrical impulses that cause it to contract follow a precise pathway through your heart. Interruption in these impulses can cause an irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia).

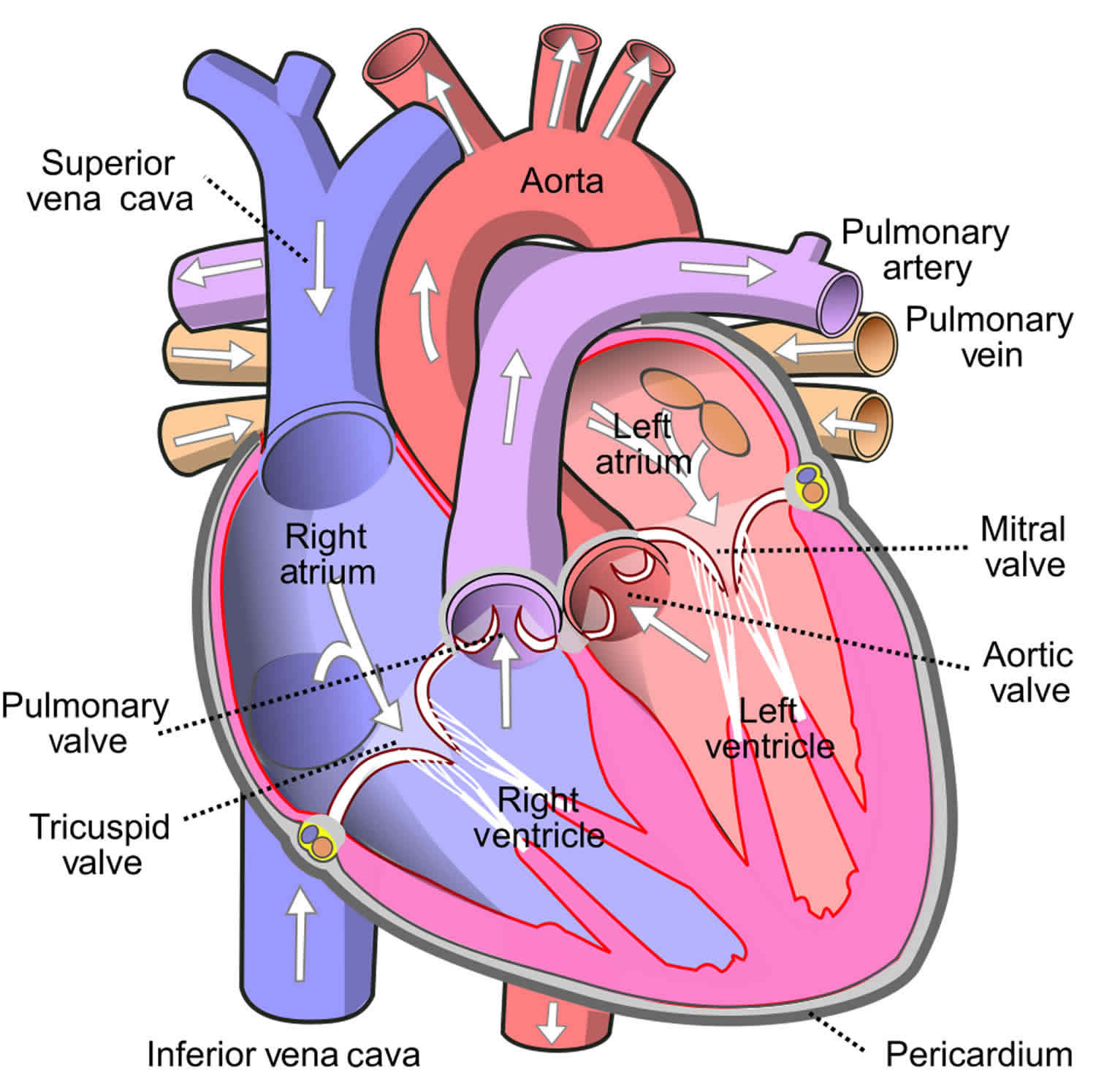

Your heart is divided into four chambers. The chambers on each half of your heart form two adjoining pumps, with an upper chamber (atrium) and a lower chamber (ventricle).

During a heartbeat, the smaller, less muscular atria contract and fill the relaxed ventricles with blood. This contraction starts after the sinus node — a small group of cells in your right atrium — sends an electrical impulse causing your right and left atria to contract.

The impulse then travels to the center of your heart, to the atrioventricular node, which lies on the pathway between your atria and your ventricles. From here, the impulse exits the atrioventricular node and travels through your ventricles, causing them to contract and pump blood throughout your body.

Figure 1. Normal human heart

Figure 2. Human heart electrical conduction system

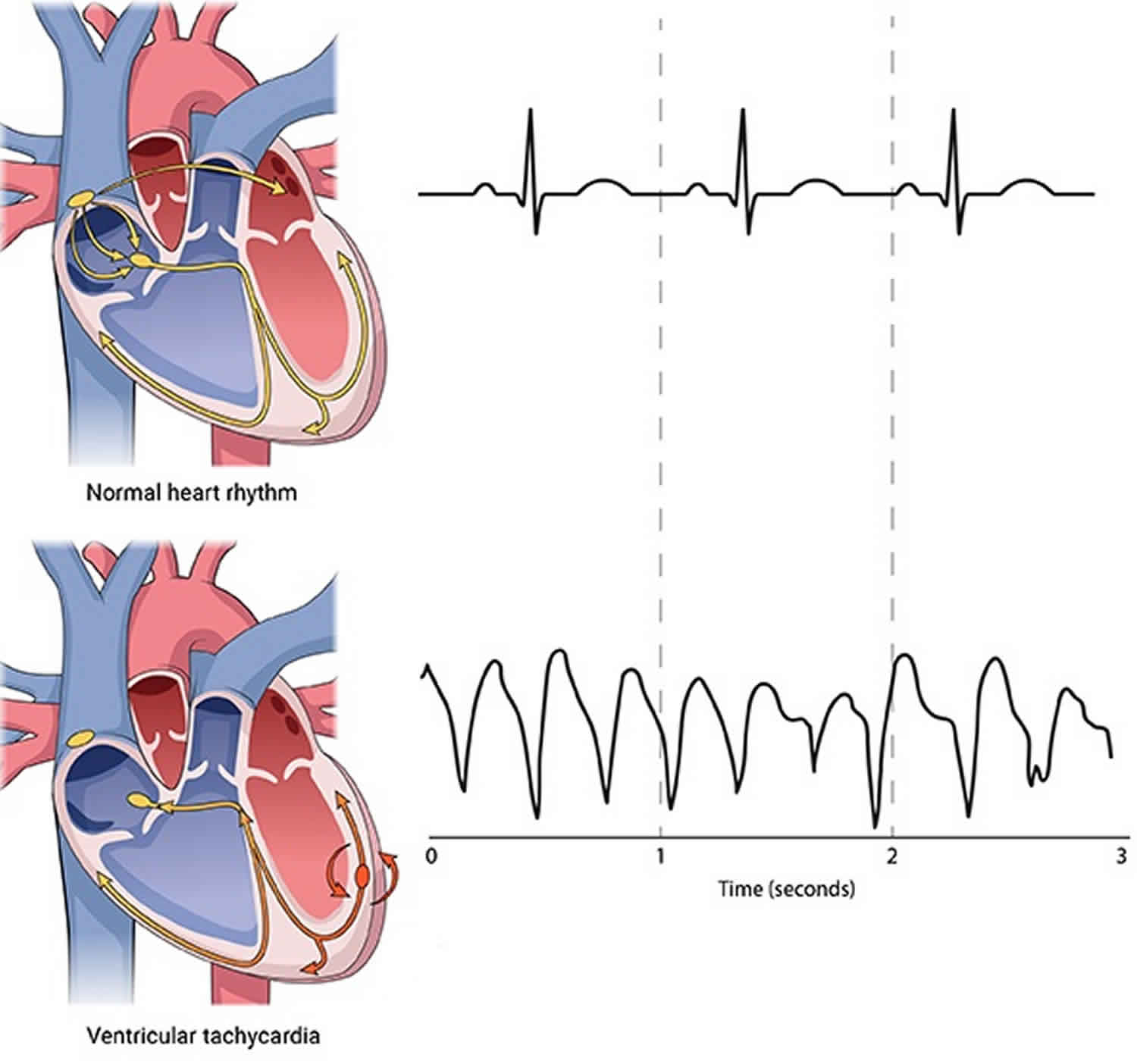

Figure 3. Ventricular fibrillation

If you or someone else is having ventricular fibrillation, seek emergency medical help immediately. Follow these steps:

- Call your local emergency number.

- If the person is unconscious, check for a pulse.

- If no pulse, begin CPR to help maintain blood flow to the organs until an electrical shock (defibrillation) can be given. Push hard and fast on the person’s chest — about 100 compressions a minute. It’s not necessary to check the person’s airway or deliver rescue breaths unless you’ve been trained in CPR.

Portable automated external defibrillators, which can deliver an electrical shock that may restart heartbeats, are available in an increasing number of places, such as in airplanes, police cars and shopping malls. They can even be purchased for your home.

Portable defibrillators come with built-in instructions for their use. They’re programmed to deliver a shock only when it’s needed.

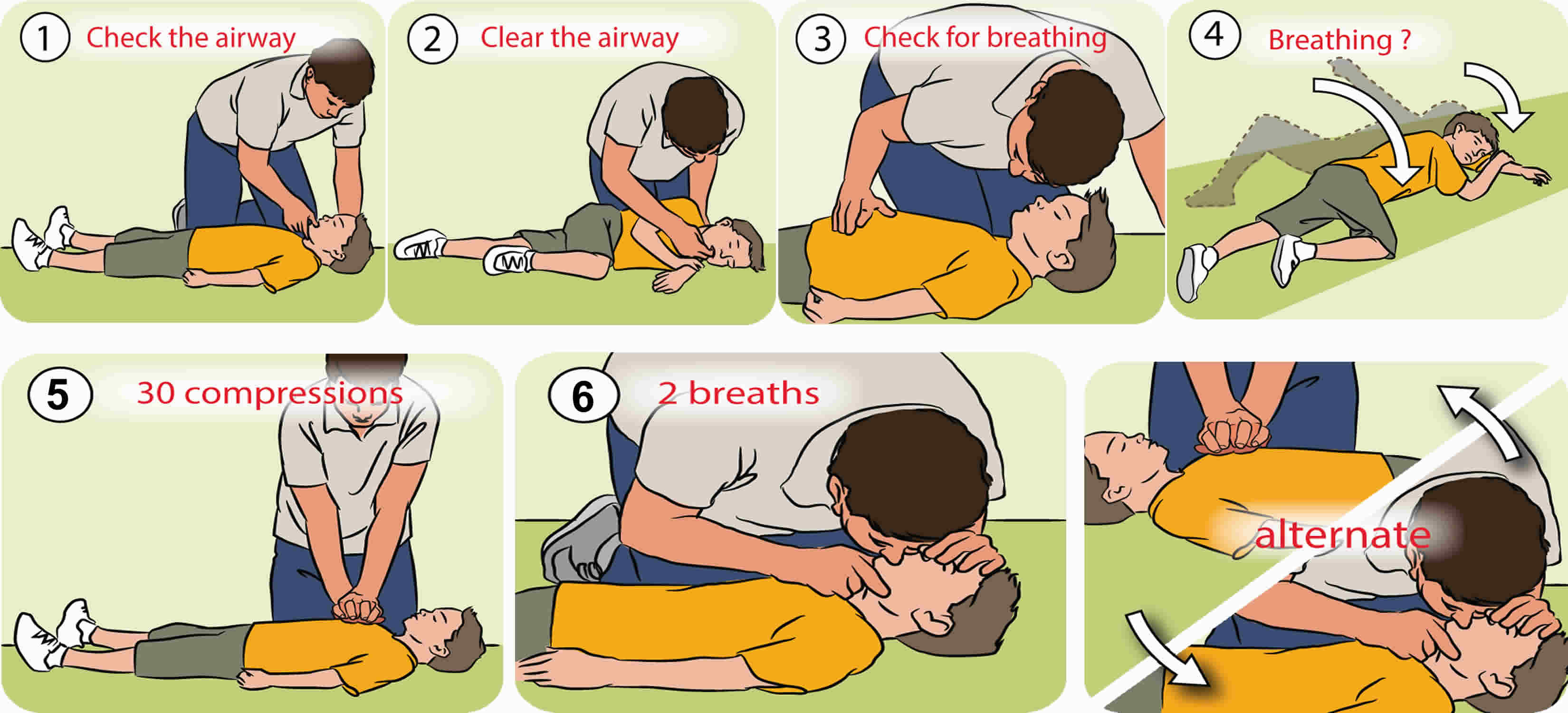

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation steps

Before you starting cardiopulmonary resuscitation, check:

- Is the environment safe for the person?

- Is the person conscious or unconscious?

- If the person appears unconscious, tap or shake his or her shoulder and ask loudly, “Are you OK?”

- If the person doesn’t respond and two people are available, have one person call 911 or the local emergency number and get the automated external defibrillator (AED), if one is available, and have the other person begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

- If you are alone and have immediate access to a telephone, call your local emergency number before beginning cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Get the automated external defibrillator (AED), if one is available.

- As soon as an automated external defibrillator (AED) is available, deliver one shock if instructed by the device, then begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Remember to spell C-A-B (compressions, airway, breathing)

The American Heart Association uses the letters C-A-B (compressions, airway, breathing) — to help people remember the order to perform the steps of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Compressions: Restore blood circulation

- Put the person on his or her back on a firm surface.

- Kneel next to the person’s neck and shoulders.

- Place the heel of one hand over the center of the person’s chest, between the nipples. Place your other hand on top of the first hand. Keep your elbows straight and position your shoulders directly above your hands.

- Use your upper body weight (not just your arms) as you push straight down on (compress) the chest at least 2 inches (approximately 5 centimeters) but not greater than 2.4 inches (approximately 6 centimeters). Push hard at a rate of 100 to 120 compressions a minute.

- If you haven’t been trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, continue chest compressions until there are signs of movement or until emergency medical personnel take over. If you have been trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, go on to opening the airway and rescue breathing.

Airway: Open the airway

- If you’re trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and you’ve performed 30 chest compressions, open the person’s airway using the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver. Put your palm on the person’s forehead and gently tilt the head back. Then with the other hand, gently lift the chin forward to open the airway.

Breathing: Breathe for the person

Rescue breathing can be mouth-to-mouth breathing or mouth-to-nose breathing if the mouth is seriously injured or can’t be opened.

- With the airway open (using the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver), pinch the nostrils shut for mouth-to-mouth breathing and cover the person’s mouth with yours, making a seal.

- Prepare to give two rescue breaths. Give the first rescue breath — lasting one second — and watch to see if the chest rises. If it does rise, give the second breath. If the chest doesn’t rise, repeat the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver and then give the second breath. Thirty chest compressions followed by two rescue breaths is considered one cycle. Be careful not to provide too many breaths or to breathe with too much force.

- Resume chest compressions to restore circulation.

- As soon as an automated external defibrillator (AED) is available, apply it and follow the prompts. Administer one shock, then resume cardiopulmonary resuscitation — starting with chest compressions — for two more minutes before administering a second shock. If you’re not trained to use an AED, an emergency medical operator may be able to guide you in its use. If an AED isn’t available, go to step 5 below.

- Continue cardiopulmonary resuscitation until there are signs of movement or emergency medical personnel take over.

Hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation

To carry out a chest compression:

- Place the heel of your hand on the breastbone at the center of the person’s chest. Place your other hand on top of your first hand and interlock your fingers.

- Position yourself with your shoulders above your hands.

- Using your body weight (not just your arms), press straight down by 5-6cm (2-2.5 inches) on their chest.

- Keeping your hands on their chest, release the compression and allow the chest to return to its original position.

- Repeat these compressions at a rate of 100 to 120 times per minute until an ambulance arrives or you become exhausted.

When you call for an ambulance, telephone systems now exist that can give basic life-saving instructions, including advice about CPR. These are now common and are easily accessible with mobile phones.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation with rescue breaths

If you’ve been trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, including rescue breaths, and feel confident using your skills, you should give chest compressions with rescue breaths. If you’re not completely confident, attempt hands-only CPR instead (see above).

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for adults

- Place the heel of your hand on the center of the person’s chest, then place the other hand on top and press down by 5-6cm (2-2.5 inches) at a steady rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute.

- After every 30 chest compressions, give two rescue breaths.

- Tilt the casualty’s head gently and lift the chin up with two fingers. Pinch the person’s nose. Seal your mouth over their mouth and blow steadily and firmly into their mouth for about one second. Check that their chest rises. Give two rescue breaths.

- Continue with cycles of 30 chest compressions and two rescue breaths until they begin to recover or emergency help arrives.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for children over 1 year

- Step 1: If a child is unconscious, the first step is to check his mouth for anything blocking the airway. This could include his tongue, food, vomit or blood.

- Step 2: If you find a blockage, roll him onto his side, keeping his top leg bent. This is the recovery position. Clear blockages with your fingers, then check for breathing.

- Step 3: If you find no blockages, check for breathing and look for chest movements. Listen for breathing sounds, or feel for breath on your cheek.

- Step 4: If the child is breathing, gently roll him onto his side and into the recovery position. Phone your local emergency services number and check regularly for breathing and response until the ambulance arrives. If the child is not breathing and responding, send for help. Phone local emergency services number and start CPR: 30 chest compressions, 2 breaths (if two people are conducting CPR, give two breaths after every 15 chest compressions).

- Step 5: Put the heels of your hands in the center of the child’s chest. Using the heel of your hand, give 30 compressions (if two people are conducting CPR, give two breaths after every 15 chest compressions). Each compression should depress the chest by about one third (at least 2 inches or approximately 5 centimeters, but not greater than 2.4 inches or approximately 6 centimeters).

- Step 6: After 30 compressions, take a deep breath, seal your mouth over the child’s mouth, pinch his nose and give two steady breaths. Make sure the child’s head is tilted back to open his airway.

- Step 7: Keep giving 30 compressions then 2 breaths until medical help arrives. If the child starts breathing and responding, turn him into the recovery position. Keep watching his breathing and be ready to start CPR again at any time.

Figure 2. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for for children over 1 year

Ventricular fibrillation causes

Ventricular fibrillation is caused by changes to heart tissue. The most common cause of ventricular fibrillation is a problem in the electrical impulses traveling through your heart after a first heart attack due to coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) or problems resulting from a scar in your heart’s muscle tissue from a previous heart attack. In survivors of cardiac arrest, coronary heart disease with over 75% stenosis is observed in 40%-86% of patients, depending on the age and sex of the population studied. In postmortem studies of people who have died from ventricular fibrillation, extensive atherosclerosis is the most common pathologic finding. Ventricular fibrillation can also occur suddenly as a result of exertion or stress, imbalances in the blood, medicines, or problems with electrical signals in the heart. Most cases of ventricular fibrillation are linked to some form of heart disease. Typically, ventricular fibrillation is set off by a trigger, and the irregular heartbeat can continue if there is a problem in the heart. Sometimes the cause of an ventricular fibrillation is unknown.

The most common cause of ventricular fibrillation is a heart attack. However, ventricular fibrillation can occur whenever the heart muscle does not get enough oxygen. Ventricular fibrillation can also occur during any of the following conditions or situations 1:

- Electric shock administered during cardioversion

- Electric shock caused by accidental contact with improperly grounded equipment

- Heart attack or angina

- Heart disease that is present at birth (congenital)

- Heart muscle disease in which the heart muscle becomes weakened and stretched or thickened

- Heart surgery

- Sudden cardiac death (commotio cordis); most often occurs in athletes who have had a sudden blow to the area directly over the heart

- Medicines

- Very high or very low potassium levels in the blood

- Antiarrhythmic drug administration

- Hypoxia

- Ischemia

- Atrial fibrillation with very rapid ventricular rates in the presence of preexcitation

- Competitive ventricular pacing to terminate ventricular tachycardia (VT) (including that delivered by an implantable device)

Most people with ventricular fibrillation have no history of heart disease. However, they often have heart disease risk factors, such as smoking, high blood pressure, and diabetes.

Some cases of ventricular fibrillation begin as a rapid heartbeat called ventricular tachycardia (VT). This rapid but regular beating of the heart is caused by abnormal electrical impulses that start in the ventricles.

Most ventricular tachycardia occurs in people with a heart-related problem, such as scars or damage from a heart attack. Sometimes ventricular tachycardia can last less than 30 seconds (nonsustained) and may not cause symptoms. But ventricular tachycardia may be a sign of more-serious heart problems.

If ventricular tachycardia lasts more than 30 seconds, it will usually lead to palpitations, dizziness or fainting. Untreated ventricular tachycardia will often lead to ventricular fibrillation.

Risk factors for ventricular fibrillation

Factors that may increase your risk of ventricular fibrillation include:

- A previous episode of ventricular fibrillation

- A previous heart attack

- A heart defect you’re born with (congenital heart disease)

- Heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy)

- Injuries that cause damage to the heart muscle, such as electrocution

- Use of illegal drugs, such as cocaine or methamphetamine

- Significant electrolyte abnormalities, such as with potassium or magnesium.

Ventricular fibrillation prevention

If you have one first-degree relative — a parent, sibling or child — with an inherited heart condition (congenital heart disease), talk with your doctor about genetic screening. Identifying an inherited heart problem early can guide preventive care and reduce your risk of complications.

Ventricular fibrillation symptoms

A person who has a ventricular fibrillation episode can suddenly collapse or become unconscious. This happens because the brain and muscles are not receiving blood from the heart.

Early signs and symptoms

A condition in which the lower chambers of your heart beat too rapidly (ventricular tachycardia or VT) can lead to ventricular fibrillation. Signs and symptoms of ventricular tachycardia include:

- Chest pain

- Rapid heartbeat (tachycardia)

- Dizziness

- Nausea

- Shortness of breath

- Loss of consciousness

Ventricular fibrillation complications

Ventricular fibrillation is the most frequent cause of sudden cardiac death. The condition’s rapid, erratic heartbeats cause the heart to abruptly stop pumping blood to the body. The longer the body is deprived of blood, the greater the risk of damage to your brain and other organs. Death can occur within minutes.

Ventricular fibrillation must be treated immediately with defibrillation, which delivers an electrical shock to the heart and restores normal heart rhythm. The rate of long-term complications and death is directly related to the speed with which you receive defibrillation.

Ventricular fibrillation diagnosis

Ventricular fibrillation is always diagnosed in an emergency situation. Your doctors will know if you’re in ventricular fibrillation based on results from:

Heart monitoring. A heart monitor that will read the electrical impulses that make your heart beat will show that your heart is beating erratically or not at all.

Pulse check. In ventricular fibrillation, there will be no pulse.

Tests to diagnose the cause of ventricular fibrillation

To find out what caused your ventricular fibrillation, you’ll have additional tests, which can include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG). This test records the electrical activity of your heart via electrodes attached to your skin. Impulses are recorded as waves displayed on a monitor or printed on paper. Because injured heart muscle doesn’t conduct electrical impulses normally, the ECG may show that a heart attack has occurred or is in progress.

- Blood tests. Emergency room doctors take samples of your blood to test for the presence of certain heart enzymes that leak into your blood if your heart has been damaged by a heart attack.

- Chest X-ray. An X-ray image of your chest allows your doctor to check the size and shape of your heart and its blood vessels.

- Echocardiogram. This test uses sound waves to produce an image of your heart. During an echocardiogram, sound waves are directed at your heart from a transducer, a wandlike device, held on your chest. Processed electronically, the sound waves provide video images of your heart.

- Coronary catheterization (angiogram). To determine if your coronary arteries are narrowed or blocked, a liquid dye is injected through a long, thin tube (catheter) that’s fed through an artery, usually in your leg, to the arteries in your heart. The dye makes your arteries become visible on X-ray, revealing areas of blockage.

- Cardiac computerized tomography (CT). In a cardiac CT scan, you lie on a table inside a doughnut-shaped machine. An X-ray tube inside the machine rotates around your body and collects images of your heart and chest.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). For a cardiac MRI, you lie on a table inside a long tubelike machine that produces a magnetic field that aligns atomic particles in some of your cells. Radio waves aimed at these aligned particles produce signals that create images of your heart.

Ventricular fibrillation treatment

Emergency treatments for ventricular fibrillation focus on restoring blood flow through your body as quickly as possible to prevent damage to your brain and other organs. After blood flow is restored through your heart, if necessary, you’ll have treatment options to help prevent future episodes of ventricular fibrillation.

Emergency treatments

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). This treatment can help maintain blood flow through the body by mimicking the pumping motion your heart makes. CPR can be performed by anyone, including family members. In a medical emergency, first call for emergency medical help, then start CPR by pushing hard and fast on the person’s chest — about 100 to 120 compressions a minute. Allow the chest to rise completely between compressions. Unless you’re trained in CPR, don’t worry about breathing into the person’s mouth. Keep up chest compressions until a portable defibrillator is available or emergency personnel arrive.

- Defibrillation. The delivery of an electrical shock through the chest wall to the heart momentarily stops the heart and the chaotic rhythm. This often allows the normal heart rhythm to resume. If a public-use automated external defibrillator (AED) is available, anyone can administer it. Most public-use automated external defibrillators voice instructions as you use them. Public-use automated external defibrillators are programmed to recognize ventricular fibrillation and send a shock only when needed.

Treatments to prevent future episodes

If your doctor finds that your ventricular fibrillation is caused by a change in the structure of your heart, such as scarred tissue from a heart attack, he or she may recommend that you take medications or have a medical procedure performed to reduce your risk of future ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest. Treatment options can include:

- Medications. Doctors use various anti-arrhythmic drugs for emergency or long-term treatment of ventricular fibrillation. A class of medications called beta blockers is commonly used in people at risk of ventricular fibrillation or sudden cardiac arrest.

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). After your condition stabilizes, your doctor is likely to recommend implantation of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is a battery-powered unit that’s implanted near your left collarbone. One or more flexible, insulated wires (leads) from the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator run through veins to your heart. The implantable cardioverter-defibrillator constantly monitors your heart rhythm. If it detects a rhythm that’s too slow, it sends an electrical signal that paces your heart as a pacemaker would. If it detects ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, it sends out low- or high-energy shocks to reset your heart to a normal rhythm. An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is more effective than drugs for preventing arrhythmia-induced cardiac arrest.

- Coronary angioplasty and stent placement. This procedure is for the treatment of severe coronary artery disease. It opens blocked coronary arteries, letting blood flow more freely to your heart. If your ventricular fibrillation was caused by a heart attack, this procedure may reduce your risk of future episodes of ventricular fibrillation. Doctors insert a long, thin tube (catheter) that’s passed through an artery, either in your leg or arm, to a blocked artery in your heart. This catheter is equipped with a special balloon tip that briefly inflates to open up a blocked coronary artery. At the same time, a metal mesh stent may be inserted into the artery to keep it open long term, restoring blood flow to your heart. Coronary angioplasty may be done at the same time as a coronary catheterization (angiogram), a procedure that doctors do first to locate narrowed arteries to the heart.

- Coronary bypass surgery. Another procedure to improve blood flow is coronary bypass surgery. Bypass surgery involves sewing veins or arteries in place at a site beyond a blocked or narrowed coronary artery (bypassing the narrowed section), restoring blood flow to your heart. This may improve the blood supply to your heart and reduce your risk of ventricular fibrillation.

Lifestyle changes

Lifestyle changes that help keep your heart as healthy as possible include:

- Eat a healthy diet. Heart-healthy foods include fruits, vegetables and whole grains, as well as lean protein sources such as soy, beans, nuts, fish, skinless poultry and low-fat dairy products. Avoid extra salt (sodium), added sugars and solid fats.

- Exercise regularly. Aim for 150 minutes a week of moderate aerobic activity, 75 minutes a week of vigorous aerobic activity, or a combination of moderate and vigorous activity.

- Stop smoking. You’re more likely to quit successfully if you take advantage of strategies proved to help. Talk with your doctor about medications that can reduce your cravings and reduce symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. Your doctor also can recommend telephone counseling and online tools — such as free services offered by the American Cancer Society — that provide critical emotional support. American Cancer Society telephone quitlines: All 50 states and the District of Columbia offer some type of free telephone-based program that links callers with trained counselors. People who use telephone counseling have twice the success rate in quitting smoking as those who don’t get this type of help. Call the American Cancer Society telephone quitline at 1-800-227-2345 to get help finding a phone counseling program in your area.

- Keep your blood pressure and cholesterol levels in a healthy range. Take medications as prescribed to correct high blood pressure (hypertension) or high cholesterol, and maintain a healthy body weight.

- Limit alcohol intake. Too much alcohol can damage your heart. If you choose to drink alcohol, do so in moderation. For healthy adults, that means up to one drink a day for women of all ages and men older than age 65, and up to two drinks a day for men age 65 and younger.

- Maintain follow-up care. Take your medications as prescribed and have regular follow-up appointments with your doctor. Tell your doctor if your symptoms worsen.

Living with ventricular arrhythmia can cause a range of difficult feelings, including fear, anger, guilt and depression. Prioritize your emotional well-being to prevent anger- and stress-related heart rhythm problems.

Some types of complementary and alternative therapies may help reduce stress, such as:

- Yoga

- Meditation

- Relaxation techniques

Getting support from your loved ones also is key to managing stress. Because arrhythmias don’t cause obvious symptoms, your friends and family may overlook your condition at times. Share your emotions and ask for help meeting your treatment goals.

Ventricular fibrillation prognosis

The chances of survival from an index ventricular fibrillation event depend on bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), rapid availability or arrival of personnel and apparatus for defibrillation and advanced life support, and transport to a hospital. Although patients with nontraumatic cardiac arrest are more likely to be successfully resuscitated from ventricular fibrillation than from any other arrhythmia, success is highly time dependent. The probability of success generally declines at a rate of 2%-10% per minute 2.

Early defibrillation often makes the difference between long-term disability and functional recovery. Placement of automated external defibrillators (AEDs) throughout communities and training of the public in their use has the potential to improve outcomes from sudden cardiac death 3.

In patients presenting to an emergency department after a witnessed episode of ventricular fibrillation, the prognosis for morbidity and mortality can be determined by calculating the cardiac arrest score, developed by McCullough and Thompson 4. This score is based on systolic blood pressure, time from loss of consciousness to return of spontaneous circulation, and neurologic responsiveness.

Even under ideal circumstances, however, only an estimated 20% of persons who have out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survive to hospital discharge. In a study of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival in New York City, only 1.4% of patients survived to hospital discharge 5. However, studies in suburban and rural areas have indicated survival rates of up to 35% 6.

Routine coronary angiography, with percutaneous coronary intervention, if indicated, along with mild therapeutic hypothermia (core temperature of 32°-34°C for 24 hours), may favorably alter the prognosis of resuscitated patients with stable hemodynamics after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest 7. In a retrospective study of cardiac arrest survivors, 65.6% of patients who underwent early coronary angiography survived to hospital discharge, compared with 48.6% of those who did not receive coronary angiography 8.

A major adverse outcome from ventricular fibrillation episodes is anoxic encephalopathy, which occurs in 30%-80% of patients. A study conducted in Minnesota on all adult survivors of out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation-related cardiac arrest from 1990-2008 found that long-term survivors had long-term memory deficits 9. A 2017 report that evaluated 2009-2013 data from the Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study registry to determine characteristics and outcomes of 3244 young adults (aged 16-35 years) who suffered out-of-hospital cardiac arrest found that factors associated with favorable neurologic outcomes included first arrest rhythms of ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia/unknown shockable rhythm, cardiac etiology, bystander-witnessed arrest, and bystander CPR 10. However, traumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest had a poor prognosis.

References- Surawicz B. Ventricular fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985 Jun. 5 (6 suppl):43B-54B.

- Ventricular fibrillation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/158712-overview

- Winkle RA. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of public-access defibrillation. Clin Cardiol. 2010 Jul. 33 (7):396-9.

- McCullough PA, Thompson RJ, Tobin KJ, Kahn JK, O’Neill WW. Validation of a decision support tool for the evaluation of cardiac arrest victims. Clin Cardiol. 1998 Mar. 21 (3):195-200.

- Lombardi G, Gallagher J, Gennis P. Outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in New York City. The Pre-Hospital Arrest Survival Evaluation (PHASE) Study. JAMA. 1994 Mar 2. 271 (9):678-83.

- Waalewijn RA, de Vos R, Koster RW. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Amsterdam and its surrounding areas: results from the Amsterdam resuscitation study (ARREST) in ‘Utstein’ style. Resuscitation. 1998 Sep. 38 (3):157-67.

- Cronier P, Vignon P, Bouferrache K, et al. Impact of routine percutaneous coronary intervention after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. Crit Care. 2011. 15 (3):R122.

- Hollenbeck RD, McPherson JA, Mooney MR, et al. Early cardiac catheterization is associated with improved survival in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest without STEMI. Resuscitation. 2014 Jan. 85 (1):88-95.

- Mateen FJ, Josephs KA, Trenerry MR, et al. Long-term cognitive outcomes following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a population-based study. Neurology. 2011 Oct 11. 77 (15):1438-45.

- Chia MY, Lu QS, Rahman NH, et al, for the PAROS Clinical Research Network. Characteristics and outcomes of young adults who suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). Resuscitation. 2017 Feb. 111:34-40.