Vulvar varicosities during pregnancy

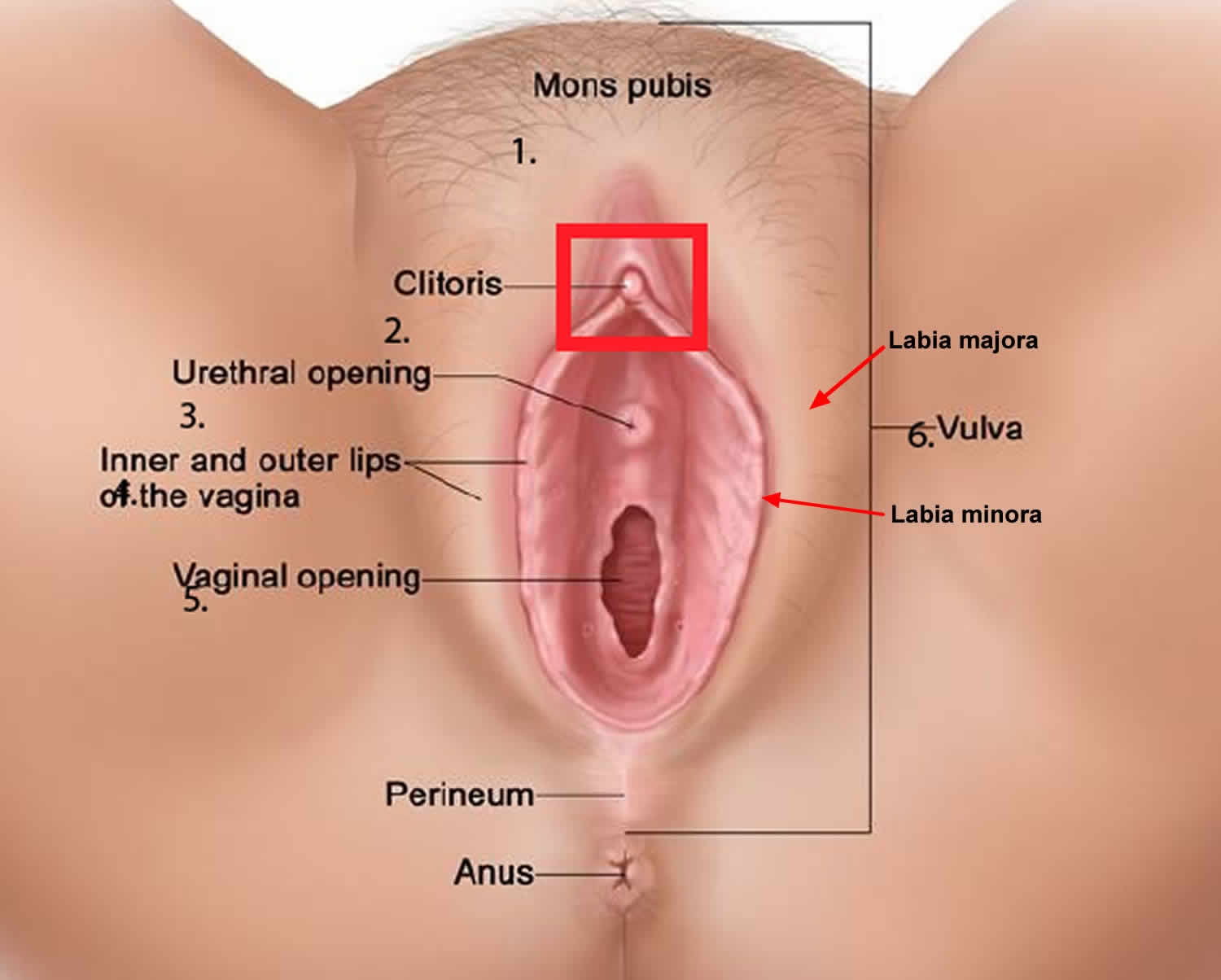

Vulvar varicosities are varicose veins (dilated veins) at the vulva or outer surface of the female genitalia (in the labia majora and labia minora) 1. Vulvar varicosities are seen in 4% of women 2, 3, most of them secondary to pregnancy and the majority of cases disappear spontaneously either immediately after childbirth or during puerperium (a period of about six weeks after childbirth), and only 4–8% persist or worsen with time 4, 5, 6, 7. Vulvar varicosities is due to the increase in blood volume to the pelvic region during pregnancy and the associated decrease in how quickly your blood flows from your lower body to your heart. As a result, blood pools in the veins of your lower extremities as well as your vulvar region, causing vulvar varicosities. Vulvar varicosities can occur alone or along with varicose veins of the legs.

Vulvar varicosities are included in pelvic venous syndromes (PVS). Pelvic venous syndromes are disorders of the pelvic venous circulation and, in 24–34% of the cases, coincide with visible varicosities on the vulva, thigh, or gluteal area 6. These disorders are developed by increased vascular pressure due to obstruction, compression, valvular incompetence, or both 5. Obesity has an effect on pelvic venous syndromes; increasing weight is associated with a higher prevalence of leg varicosities and lower prevalence of proximal vein flow disorders 8, 9, 10.

The anatomical basis for the development of vulvar varicosities relates to the connections between the veins of the pelvis and external genitals 11. Vascular drainage of the vulvar area is achieved through external pudendal veins (superficial and deep), which drain into the long saphenous vein at the saphenous opening. Ιnternal pudendal veins are the second pathway of drainage of the labia and clitoris, venae comitantes of the internal pudendal artery, and tributaries of the internal iliac vein 12. The third drainage pathway is by the vein of the round ligament running through the inguinal canal to drain to the ovarian vein 13.

It is estimated that between 4 percent and 22 percent of women and 22–34 percent of women with varicose veins of the pelvis will develop vulvar varicose veins during pregnancy, although the actual figure is most likely to be much higher with many women not developing any symptoms, or being too embarrassed to discuss the symptoms with their doctor 14. In some patients, vulvar varicosities may be associated with a chronic pelvic pain syndrome called pelvic congestion syndrome 15. Vulvar varicosities are rare during a first pregnancy and generally develop during month 5 of a second pregnancy and occurred most often in women with a history of two or more full-term pregnancies (91%). The risk increases with the number of pregnancies 16.

Vulvar varicosities don’t always cause signs and symptoms. If they occur, they might include a feeling of fullness or pressure in the vulvar area, vulvar swelling and discomfort. In extreme cases, the dilated vessels can bulge. They might look bluish and feel bumpy. Long periods of standing, exercise and sex can aggravate the condition.

During the postpartum period, perineal veins may persist and enlarge with time in 4%–8% of patients 17. Vulvar varicosities are associated with venous thromboembolic events, both during pregnancy and in the nonpregnant state, superficial dyspareunia (painful intercourse), and vulvar pain (vulvodynia) 1. Vulvar varicosities may also cause psychoemotional and family problems. It is difficult to estimate reliably the prevalence of this pathological condition, as vulvar varicosities often remain undiagnosed because of the atypical localization of the varicose veins, women’s reluctance to consult, and in some cases the absence of any discomfort.

In most cases, vulvar varicosities can be diagnosed at clinical examination, and do not require any special investigation methods. Their diagnosis requires an assessment of the state of the intrapelvic veins, and in cases of pregnancy further observation and examination in the postpartum period.

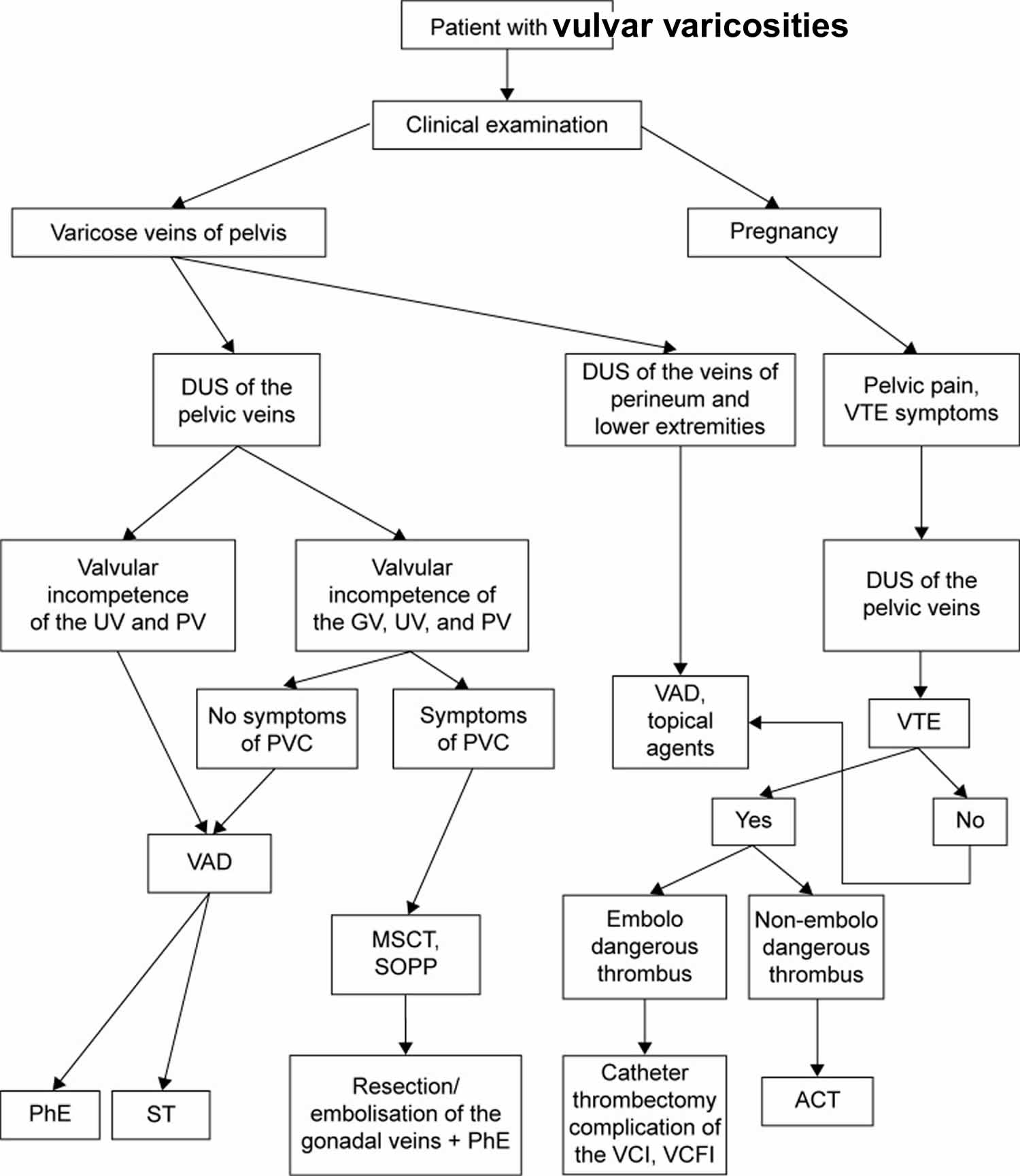

Vulvar varicosities treatment varies from purely conservative measures during pregnancy to various surgical procedures on the ovarian and vulvar veins. A diagnostic and treatment algorithm for vulvar varicosities in various clinical situations is presented in Figure 4. An individualized approach to diagnostic methods and treatment for this disorder can significantly improve the quality of care of patients with chronic venous diseases.

To feel relief:

- Get a support garment. Look for one specifically designed for vulvar varicosities. Some designs also provide support for the lower abdomen and lower back.

- Change position. Avoid standing or sitting for long periods of time.

- Elevate your legs. This can help promote circulation.

- Apply cold compresses to your vulva. This might ease your discomfort.

Vulvar varicosities likely won’t affect your mode of delivery. These veins tend to have a low blood flow. As a result, even if bleeding occurred, it could easily be controlled.

Typically, vulvar varicosities related to pregnancy go away within about six weeks after delivery.

Figure 1. The vulva

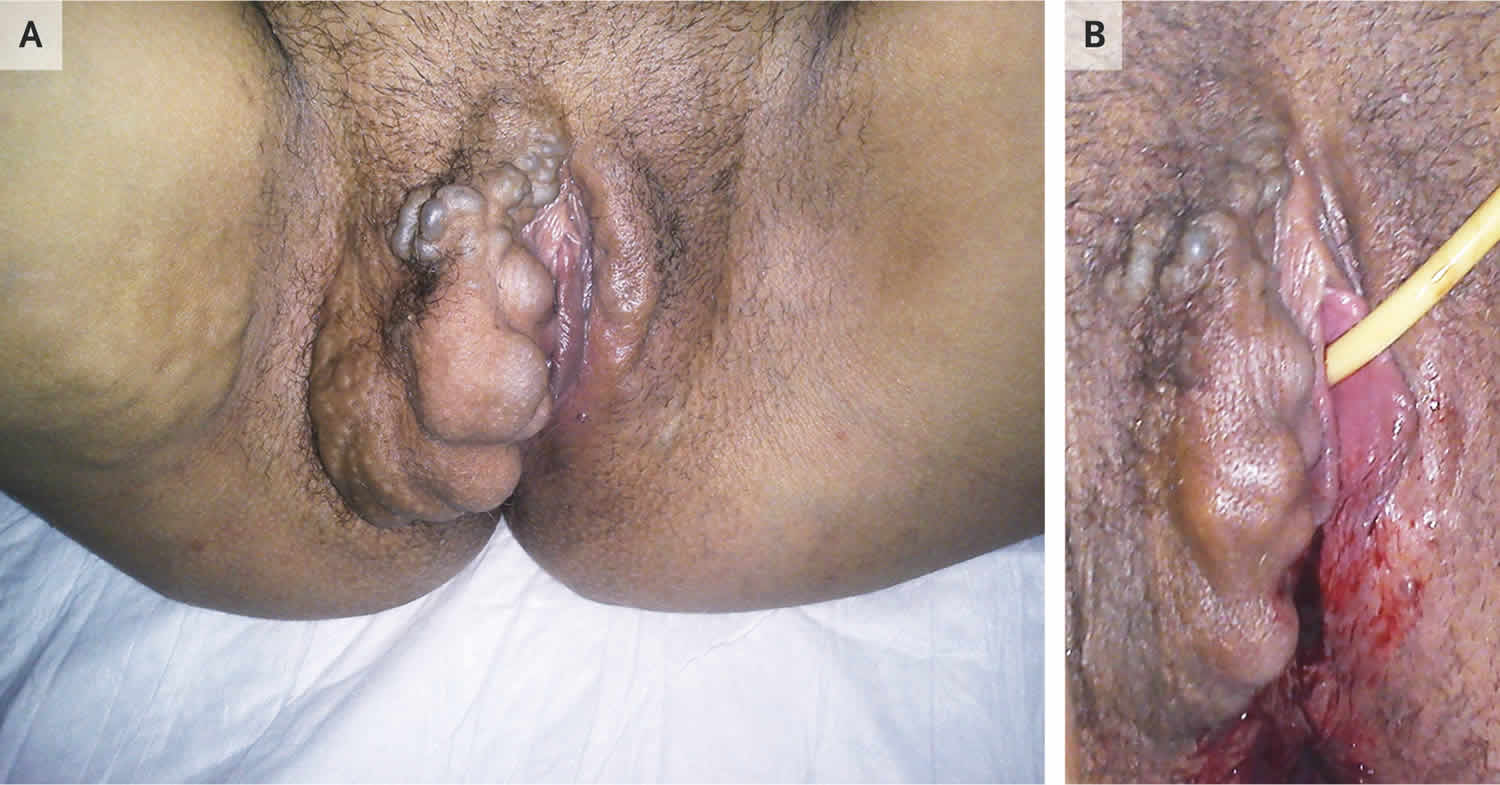

Figure 2. Vulvar varicose veins

Footnotes: A 33-year-old woman was admitted for induction of labor at 41 weeks 3 days of gestation. This was her third full-term pregnancy, and she had received regular antenatal care. Before induction, the physical examination revealed venous varicosities on the right labia majora and minora and the right vaginal wall (Panel A). Varicose veins in both legs were also noted. The patient reported that the varicosities had developed several months earlier and caused increasing discomfort and pruritus, but she had been embarrassed to mention them. She had had smaller varicosities during her previous pregnancies, with normal vaginal delivery. Vulvovaginal varicosities are common in pregnancy and usually appear in the second trimester. Possible mechanisms include compression of the inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus and hormonal changes. The presence of vulvar varicosities is not a contraindication for vaginal delivery, but clinical discretion regarding the route of delivery is required, depending on the size and location of the varicosities. In this instance, the patient underwent caesarean delivery without complications. The vulvar varicosities were substantially smaller after delivery (Panel B).

[Source 18 ]Figure 3. Thrombophlebitis of the vulvar veins. Hyperemia and edema in the area of thrombosed veins (arrow).

Figure 4. Vulvar varicosities diagnostic and treatment algorithm

Abbreviations: DUS = duplex ultrasound; VTE = venous thromboembolic event; UV = uterine vein; PV = parametrial vein; GV = gonadal (ovarian) vein; PVC = pelvic venous congestion; VAD = venoactive drug; MSCT = multislice computed tomography; SOPP = selective ovariography with pelvic phlebography; PhE = phlebectomy; ST = sclerotherapy; VCI = vena cava inferior; VCFI = vena cava-filter implantation; ACT = anticoagulant therapy.

[Source 1 ]Will the vulvar varicose veins rupture during childbirth?

It’s highly unlikely that damaged vein will rupture during childbirth. There have been a few cases of the varicose vein rupturing during pregnancy, however following the above tips, and seeking professional advice, will help prevent this from happening.

The good news is for most women is the varicose veins will resolve on their own after several months post-partum. In some cases, it can take up to a year. For a small percentage of women, however, varicose veins will not shrink or disappear after pregnancy and may require medical treatment.

Varicose veins and swelling in your legs, ankles and feet

If you look down and can’t see your ankles, you’re not alone. Many women have swelling in their legs, ankles and feet during pregnancy. Swelling may be caused by pregnancy hormones, having more fluid in your body during pregnancy, and pressure from your growing baby on the veins that carry blood to your heart.

Pressure on a vein called the inferior vena cava may cause sore, itchy, blue bulges on your legs. These are called varicose veins. They usually don’t cause problems, but they’re not pretty. You’re more likely to have them if it’s your first pregnancy or if other people in your family have them.

Here’s what you can do to help relieve varicose veins and swelling in your legs, ankles and feet:

- Don’t stand for long periods of time.

- When you’re sitting down, put your feet up. Don’t cross your legs when you sit.

- When you’re lying down, put your legs up on a pillow.

- Sleep on your left side. This takes pressure off the vein that returns blood from the lower parts of your body to your heart.

- Wear support hose or compression stockings or leggings. These fit tight all over and can help control swelling. Don’t wear socks or stockings that have a tight band of elastic around the leg.

- Do something active every day. Talk to your provider about activities that are safe during pregnancy.

- Put an ice pack on swollen areas.

If you have extreme or sudden swelling, call your doctor right away. These may be signs of a serious condition called preeclampsia. This condition can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy. It’s when a woman has high blood pressure and signs like a severe headache that mean that some of her organs aren’t working properly.

Vulvar varicosities causes

Varicose veins can develop in your vulva during pregnancy due to normal changes that occur to your body at this time, such as:

- increased blood volume

- hormonal softening of the walls of your veins

- increasing pressure on the large veins in the abdomen and pelvis as your baby grows.

Hodgkinson 19 suggested that there can be up to a 60-fold increase of blood flow in the pelvis during pregnancy, resulting in dilation of the ovarian veins. The hormonal influence of pregnancy also appears to play a major role, since estrogen and progesterone have a lytic action on elastic tissues, and cause further vasodilation. Vulvar varicosities in nulliparous women (women who haven’t given birth to a child) are caused by local venous insufficiency, with genetic predisposition likely playing a role.

Vulvar varicosities pathogenesis is poorly understood, because of the complexity and variation of the pelvic circulation 20. Sometimes the problem is isolated in the vulvar veins, whereas, when it is part of Pelvic Congestion Syndrome, connection between two veins and drainage in both great saphenous and internal iliac impede the discovery of a single affected proximal vessel. Fatty tissue participates in the pathogenesis of pelvic venous syndromes. Varicosities of the legs are more frequent at higher body mass index (overweight and obesity), whereas Pelvic Congestion Syndrome is less frequent 9, 21. A possible explanation is that excess fatty tissue in the abdominal cavity causes increasing reflux on distal tributaries of pelvic veins and long saphenous vein; however, elastic properties of the adipose tissue protect deep pelvic veins from compression 8, 10. Additionally, it is proposed that the fatty tissue actively involves the renin–angiotensin system and, subsequently, controls the vascular tone 22, 8.

Vulvar varicosities symptoms

Not all women with vulvar varicosities will be able to see them and most often they are asymptomatic 20. Some women will have visible veins around the vulva or inner thigh. Yet others will not show any visible signs but they will experience pain.

If you don’t have any physical side-effects, here are a few symptoms you can look out for:

- Pain around the pelvis or lower back, usually described as a dull ache.

- A feeling of heaviness or fullness of the vulva.

- Any pain in the vulva that gets worse after standing, sexual activity, or physical activity.

- Swelling or itchiness around the vulva.

- An increase in urination.

In rare cases, vulvar varicosities cause anxiety, discomfort, pain, and manifest as heaviness or pressure in the vulvar area, discomfort during walking or with prolonged standing or just before the onset of your peiod, painful intercourse (dyspareunia) and pruritus (itch) 23, 24.

Vulvar varicosities complications

Complications such as thrombosis (blood clot inside the vein) or bleeding are rare. A superficial thrombosis presents as a painful, red (inflammatory) swelling, and is firm to the touch. It requires examination to look for an underlying deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Spontaneous bleeding appears to be of academic interest, and in practice is not observed. Bleeding during childbirth is associated with vaginal tears or an episiotomy; internal bleeding results in formation of a hematoma (blood clot in tissue or body space), primarily affecting the labia. Vulvar varices are not an indication for a cesarean section delivery.

Vulvar varicosities diagnosis

Clinical examination of the patient standing and then lying horizontal reveals the following: soft, bluish dilatations, depressible by digital examination, with no painful point (sign of thrombosis). Often, this varicose network extends downwards to the medial aspect of the thigh, towards the long saphenous trunk, and sometimes posteriorly to the anal margin. The perfectly bilateral nature and the fact that they are associated with a varicose network in both lower limbs are reassuring.

The diagnostic test of pregnant women with vulvar varicosities is limited to duplex ultrasound of the veins of the perineum and lower extremities 25. This diagnostic test is required not only to verify the diagnosis but also to exclude latent thrombosis (blood clot inside the vein) in the inferior vena cava in the presence of subjective symptoms. Dilation of the external pudendal vein and associated reflux, which represents an obvious reason for formation of vulvar varicosities, was found in 56% of patients.

According to the American Venous Forum and Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines, patients with symptoms indicative of Pelvic Congestion Syndrome should additionally undergo contrast venography by jugular or femoral vein catheter 26, 27, 28. Varicography, which consists of direct injection of contrast into the visible varicose veins, provides additional help only in the pre-operative planning 29. Computed tomography (CT scan) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can diagnose any associated Pelvic Congestion Syndrome and identify the affected veins, which can be targeted for therapeutic interventions 27.

Vulvar varicosities treatment

Vulvar varicosities treatment is symptomatic during pregnancy and curative afterward if the vulvar varicosities persist. The good news about vulvar varicose veins during pregnancy is that they are likely to disappear spontaneously within a few days of giving birth and rarely persist one month later.

Follow-up of 25 patients who developed vulvar varicosities during pregnancy for at least 1 year after childbirth revealed that dilated vulvar veins persisted in only 20% of patients 1. A reduction in vulvar varicosity was observed from the first days after birth, and most patients reported their complete disappearance within 2–8 months (5.8±1.04 months on average).

An association was found between the end of lactation period or a reduction in breastfeeding and the rate of vulvar varicosity disappearance: the shorter the lactation period, the earlier the varicose veins of the perineum disappeared, and vice versa. This once again indicates that hormonal changes play an important role in the development of varicose veins of the lower extremities, in the perineum, and in the small pelvis during pregnancy.

During pregnancy

Here are few safe ways you can treat the symptoms and prevent further damage to the varicose veins:

- Avoid standing still for any length of time—move, walk, change positions.

- Strictly avoid any squatting (kneel or sit on a stool). This is very important.

- Avoid constipation (this increases the strain pressure on your veins). Make sure your bowel motions are soft and easy to pass and sit in the emptying position using hand support under your perineum. Remember:

- maintain curve in lower back

- lean forward from the hips

- allow abdomen to relax forward

- always keep breathing

- no straining

- a small footstool may enhance position.

- Avoid any other activities that cause straining such as lifting, pushing, pulling, sneezing or coughing. When you cannot avoid any of these activities, use your hands or a rolled towel to help support your perineum.

- Lie down to rest–often. Sitting does not relieve the pressure on this area. Lying on your side is best.

- Ice fingers – cold compresses may give temporary relief. A trick some women use after giving birth is filling a rubber glove with cold water and ice. Using the glove as an ice-pack can help reduce swelling and relieve pain. Please note: ice should not be held on the area for longer than 30 minutes to 1 hour. Ice can reduce the blood flow needed for your body to heal.

- Practise your pelvic floor exercises regularly this will help blood to circulate better in the area and strengthen the supporting tissues around the veins.

- Supportive underwear – using support garments to assist in reducing the symptoms of vulval varicosities. Many women also find that full leg support stockings can some provide relief. You can also try supportive underwear (with a gusset) or bike pants with double sanitary pads inside. You will get the best results if you apply garments and support hosiery before getting out of bed in the morning (i.e. before gravity has taken effect).

- Pruritus (itch) is treated by bathing with a foaming solution without soap, and then a water-based zinc oxide paste. Pain and heaviness are treated with high-dose phlebotonic agents 30.

- Aromatherapy – some aromatherapists suggest using diluted geranium oil in a bath or soaked into a gauze pad as a direct compress to the area.

It should be remembered that pregnancy is a risk factor for venous thrombosis.

- Bleeding requires compression therapy.

- Sclerotherapy is always possible during pregnancy. It does not carry any particular risks either for the woman or the fetus. It is rarely performed because its beneficial results are uncertain in an unfavorable hormonal context.

After pregnancy

A month after delivery, vulvar varices most often have disappeared. Small, asymptomatic residual vulvar varicose veins are seen again after 1 year. Large or symptomatic varices are managed with curative therapy. Sclerotherapy is the preferred method because it is very effective on these thin-walled varices. It is administered most often in a very superficial varicose vein blister under visual control using a very fine gauge needle (30G) and a liquid sclerosing product. Sclerosing foamy products are more thrombogenic and are not indicated here. The dose used is 1 cc of 0.5% or 1% Aetoxisclerol; or 0.33% or 0.5%.Trombovar.

Varices in the groin or the mons veneris can be treated with echosclerosis. Care should be taken to avoid the external pudendal artery for which an accidental injection produces disastrous lesions in the vascular area downstream. Identification with the duplex color technique, by greatly increasing gains in the future area of injection, is essential to keeping in mind that “what is not seen exists” 31.

Phlebectomy remains possible for perineal varices 32, but is little performed because of the good results obtained with sclerotherapy. The same holds true for ligation of the labial or marginal perforating veins with the patient in the lithotomy position after identification by sonography.

References- Gavrilov SG. Vulvar varicosities: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:463‐475. Published 2017 Jun 28. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S126165 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5500487

- Leung S.W., Leung P.L., Yuen P.M., Rogers M.S. Isolated vulval varicosity in the non-pregnant state: A case report with review of the treatment options. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005;45:254–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00400.x

- Naous J., Siqueira L. A vulvovaginal mass in a 16-year-old adolescent: A case report. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016;29:e17–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.09.003

- Theodorou G, Khomsi F, Bouzerda-Brahami K, Bouquet de Jolinière J, Feki A. Surgical management of a large postoperative vulvar haematoma following vulvar phlebectomy and ovarian vein embolization for vulvar varicose veins: A case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2020 May 23;27:e00225. doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2020.e00225

- Hobbs JT. The pelvic congestion syndrome. Br J Hosp Med. 1990 Mar;43(3):200-6.

- Fassiadis N. Treatment for pelvic congestion syndrome causing pelvic and vulvar varices. Int Angiol. 2006 Mar;25(1):1-3.

- Gavrilov SG. Vulvar varicosities: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Jun 28;9:463-475. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S126165

- Nanavati R., Jasinski P., Adrahtas D., Gasparis A., Labropoulos N. Correlation between pelvic congestion syndrome and body mass index. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018;67:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.06.115

- Wrona M., Jöckel K.H., Pannier F., Bock E., Hoffmann B., Rabe E. Association of venous disorders with leg symptoms: Results from the Bonn Vein Study 1. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2015;50:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.05.013

- Handel L.A.N., Shetty R., Sigman M. The relationship between varicoceles and obesity. J. Urol. 2006;176:2138–2140. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.023

- Thomas ML, Fletcher EW, Andress MR, Cockett FB. The venous connections of vulval varices. Clin Radiol. 1967;18:313–317.

- Standring S. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences; New York, UK: 2008.

- Lea Thomas M., Fletcher E.W.L., Andress M.R., Cockett F.B. The venous connections of vulval varices. Clin. Radiol. 1967;18:313–317. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(67)80080-1

- Fassiadis N. Treatment for pelvic congestion syndrome causing pelvic and vulvar varices. Int Angiol. 2006;25:1–3.

- Kim, Anna S. MD; Greyling, Laura A. MD; Davis, Loretta S. MD Vulvar Varicosities, Dermatologic Surgery: March 2017 – Volume 43 – Issue 3 – p 351-356 doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001008

- Van Cleef JF. Traitement des varices vulvaires et pelviennes. Hygie. 2006;29:11.

- Bell D, Kane PB, Liang S, Conway C, Tornos C. Vulvar varices: an uncommon entity in surgical pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2007;26:99–101.

- Severe Vulvovaginal Varicosities in Pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:2123 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm1715053

- Hodgkinson C.P. Physiology of the ovarian veins during pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Jan. 1953;1(1):26–37.

- Giannouli A, Tsinopoulou VR, Tsitsika A, Deligeoroglou E, Bacopoulou F. Vulvar Varicosities in an Adolescent Girl with Morbid Obesity: A Case Report. Children (Basel). 2021 Mar 7;8(3):202. doi: 10.3390/children8030202

- Brand F.N., Dannenberg A.L., Abbott R.D., Kannel W.B. The epidemiology of varicose veins: The Framingham Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1988;4:96–101. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)31203-0

- Goossens G.H., Blaak E.E., Van Baak M.A. Possible involvement of the adipose tissue renin-angiotensin system in the pathophysiology of obesity and obesity-related disorders. Obes. Rev. 2003;4:43–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2003.00091.x

- Rozenblit A.M., Ricci Z.J., Tuvia J., Amis E.S.J. Incompetent and dilated ovarian veins: a common CT finding in asymptomatic parous women. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. Jan. 2001;176(1):119–122. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.1.1760119

- Bell D., Kane P.B., Liang S., Conway C., Tornos C. Vulvar varices: an uncommon entity in surgical pathology. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. Jan. 2007;26(1):99–101. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000215304.62771.19

- Gavrilov S.G. Vulvar varicosities: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Int. J. Women’s Health. 2017;9:463–475. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S126165

- Gloviczki P., Comerota A.J., Dalsing M.C., Eklof B.G., Gillespie D.L., Gloviczki M.L., Lohr J.M., McLafferty R.B., Meissner M.H., Murad M.H., et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;53:2S–48S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.01.079

- Koo S., Fan C.-M. Pelvic congestion syndrome and pelvic varicosities. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2014;17:90–95. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2014.02.005

- Phillips G.W.L., Paige J., Molan M.P. A comparison of colour duplex ultrasound with venography and varicography in the assessment of varicose veins. Clin. Radiol. 1995;50:20–25. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(05)82960-5

- Mathis BV, Miller JS, Lukens ML, Paluzzi MW. Pelvic congestion syndrome: a new approach to an unusual problem. Am Surg. 1995 Nov;61(11):1016-8.

- Simsek M, Burak F, Taskin O. Effects of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (Daflon) on pelvic pain in women with laparoscopically diagnosed pelvic congestion syndrome: a randomised crossover trial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2007;34:96-98.

- Jin KN, Lee W, Jae HJ, Yin YH, Chung JW, Park JH. Venous reflux from the pelvis and vulvoperineal region as a possible cause of lower extremity varicose veins: diagnosis with computed tomographic and ultrasonographic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:763-769.

- Dortu J, Dortu JA. The external pudendal veins. An anatomo-clinical study, their treatment by ambulatory phlebectomy (Muller method). Phlébologie. 1990;43:329-355.