Dementia

Dementia is not a disease, but a collection of symptoms that result from damage to the brain or disorders affecting the brain 1. Dementia is not a specific disease 2. Dementia affects thinking, behavior, remembering, reasoning and behavioral abilities to such an extent that it interferes with a person’s daily life and activities 3. In dementia, the brain function is affected enough to interfere with the person’s normal social or working life. People with dementia may not be able to think well enough to do normal activities, such as getting dressed or eating. They may lose their ability to solve problems or control their emotions 2. Their personalities may change 2. They may become agitated or see things (hallucinate) that are not there 2.

Memory loss is a common symptom of dementia 2. However, memory loss by itself does not mean you have dementia 2. People with dementia have serious problems with two or more brain functions, such as memory and language 2. People with advanced dementia may not recognise close family and friends, they may not remember where they live or know where they are. They may find it impossible to understand simple pieces of information, carry out basic tasks or follow instructions.

Although dementia is common in very elderly people, up to half of all people age 85 or older may have some form of dementia. Dementia is not a normal part of aging 2, 3. Many people live into their 90s and beyond without any signs of dementia. One type of dementia, fronto-temporal disorders, is more common in middle-aged than older adults.

Dementia ranges in severity from the mildest stage, when it is just beginning to affect a person’s functioning, to the most severe stage, when the person must depend completely on others for basic activities of living 4. As dementia progresses, memory loss and difficulties with communication often become very severe. It’s common for people with dementia to have increasing difficulty speaking and they may eventually lose the ability to speak altogether. It’s important to keep trying to communicate with them and to recognise and use other, non-verbal means of communication, such as expression, touch and gestures. In the later stages, the person is likely to neglect their own health and require constant care and attention.

Many people with dementia gradually become less able to move about unaided and may appear increasingly clumsy when carrying out everyday tasks. Some people may eventually be unable to walk and may become bedbound. Bladder incontinence is common in the later stages of dementia and some people will also experience bowel incontinence.

Loss of appetite and weight loss are common in the later stages of dementia. It’s important that people with dementia get help at mealtimes to ensure they eat enough.

Many people have trouble eating or swallowing and this can lead to choking, chest infections and other problems.

Signs and symptoms of dementia result when once-healthy neurons (nerve cells) in the brain stop working, lose connections with other brain cells, and die. While everyone loses some neurons as they age, people with dementia experience far greater loss 4.

Memory loss, though common, is not the only sign of dementia. For a person to have dementia, he or she must have 4:

- Two or more core mental functions that are impaired. These functions include memory, language skills, visual perception, and the ability to focus and pay attention. These also include cognitive skills such as the ability to reason and solve problems.

- A loss of brain function severe enough that a person cannot do normal, everyday tasks.

In addition, some people with dementia cannot control their emotions. Their personalities may change. They can have delusions, which are strong beliefs without proof, such as the idea that someone is stealing from them. They also may hallucinate, seeing or otherwise experiencing things that are not real.

The causes of dementia can vary, depending on the types of brain changes that may be taking place. Many different diseases can cause dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease and stroke 2. Other dementias include Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal disorders, and vascular dementia 4. It is common for people to have mixed dementia—a combination of two or more disorders, at least one of which is dementia 4. For example, some people have both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Drugs are available to treat some of these diseases. While these drugs cannot cure dementia or repair brain damage, they may improve symptoms or slow down the disease 2.

Who gets dementia?

Most people with dementia are older, but it is important to remember that not all older people get dementia. Dementia is NOT a normal part of ageing.

Dementia can happen to anybody, but it is more common after the age of 65 years. People in their 40s and 50s can also have dementia.

Do memory problems always mean Alzheimer’s disease?

Many people worry about becoming forgetful. They think forgetfulness is the first sign of Alzheimer’s disease. But not all people with memory problems have Alzheimer’s disease 5. Other causes for memory problems can include aging, medical conditions, emotional problems, mild cognitive impairment, or another type of dementia.

Early signs of dementia

There are some common early symptoms that may appear some time before a diagnosis of dementia. These include:

- memory loss

- difficulty concentrating

- finding it hard to carry out familiar daily tasks, such as getting confused over the correct change when shopping

- struggling to follow a conversation or find the right word

- being confused about time and place

- mood changes

These symptoms are often mild and may get worse only very gradually. It’s often termed “mild cognitive impairment” (MCI) as the symptoms are not severe enough to be diagnosed as dementia.

You might not notice these symptoms if you have them, and family and friends may not notice or take them seriously for some time. In some people, these symptoms will remain the same and not worsen. But some people with MCI (mild cognitive impairment) will go on to develop dementia.

Dementia is not a natural part of ageing. This is why it’s important to talk to a doctor sooner rather than later if you’re worried about memory problems or other symptoms.

What is Mild Cognitive Impairment?

Some forgetfulness can be a normal part of aging. However, some people have more memory problems than other people their age. This condition is called mild cognitive impairment (MCI) 6. Mild cognitive impairment is a clinical syndrome in which an individual experiences a mild but noticeable and measurable decline in cognitive abilities, including memory, judgment, language and thinking skills that are greater than normal age-related changes, but the loss doesn’t significantly interfere with your ability to handle everyday activities 7. Mild cognitive impairment is an intermediate stage between normal cognitive changes that may occur with age and more serious symptoms that indicate dementia 8. If you have mild cognitive impairment, you may be aware that your memory or mental function has “slipped.” Your family and close friends also may notice a change. People with mild cognitive impairment can take care of themselves and do their normal activities 9. Mild cognitive impairment is characterized by problems with memory, language, thinking or judgment.

People with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) have a significantly increased risk, but not a certainty, of developing dementia. Overall, about 1% to 3% of older adults develop dementia every year. Numerous international population-based studies have been conducted to document the frequency of mild cognitive impairment, estimating its prevalence to be between 15% and 20% in persons 60 years and older, making it a common condition encountered by clinicians 8. Studies suggest that around 8% to 15% of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) go on to develop dementia each year 8.

Mild cognitive impairment memory problems may include:

- Losing things often

- Forgetting to go to events and appointments

- Having more trouble coming up with words than other people of the same age

If you have mild cognitive impairment (MCI), you may also experience:

- Depression

- Irritability and aggression

- Anxiety

- Apathy

If you have mild cognitive impairment (MCI), you may be aware that your memory or mental function has “slipped.” Your family and close friends also may notice a change. But these changes aren’t severe enough to significantly interfere with your daily life and usual activities.

Mild cognitive impairment may increase your risk of later developing dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease or other neurological conditions. But some people with mild cognitive impairment never get worse, and a few eventually get better.

Experts classify mild cognitive impairment based on the thinking skills affected:

- Amnestic mild cognitive impairment: mild cognitive impairment that primarily affects memory. A person may start to forget important information that he or she would previously have recalled easily, such as appointments, conversations or recent events.

- Nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment: mild cognitive impairment that affects thinking skills other than memory, including the ability to make sound decisions, judge the time or sequence of steps needed to complete a complex task, or visual perception.

Researchers have found that more people with mild cognitive impairment than those without it go on to develop Alzheimer’s disease. However, not everyone who has mild cognitive impairment develops Alzheimer’s disease. About 8 of every 10 people who fit the definition of amnestic mild cognitive impairment go on to develop Alzheimer’s disease within 7 years 9. In contrast, 1 to 3 percent of people older than 65 who have normal cognition will develop Alzheimer’s disease in any one year 9.

Research suggests genetic factors may play a role in who will develop mild cognitive impairment, as they do in Alzheimer’s disease 9. Studies are underway to learn why some people with mild cognitive impairment progress to Alzheimer’s disease and others do not.

Symptoms of Mild Cognitive Impairment

Your brain, like the rest of your body, changes as you grow older. Many people notice gradually increasing forgetfulness as they age. It may take longer to think of a word or to recall a person’s name. But consistent or increasing concern about your mental performance may suggest mild cognitive impairment (MCI). People with amnestic mild cognitive impairment have more memory problems than normal for people their age, but their symptoms are not as severe as those of people with Alzheimer’s disease 9. For example, they do not experience the personality changes or other problems that are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease 9. People with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) are still able to carry out their normal daily activities 9.

Cognitive issues that may indicate possible mild cognitive impairment (MCI) if you experience any or all of the following:

- You forget things more often.

- You forget important events such as appointments or social engagements.

- You lose your train of thought or the thread of conversations, books or movies.

- You feel increasingly overwhelmed by making decisions, planning steps to accomplish a task or understanding instructions.

- You start to have trouble finding your way around familiar environments.

- You become more impulsive or show increasingly poor judgment.

- Your family and friends notice any of these changes.

Signs of Mild Cognitive Impairment

Signs of Mild Cognitive Impairment include 9:

- Losing things often.

- Forgetting to go to events or appointments.

- Having more trouble coming up with words than other people of the same age.

Movement difficulties and problems with the sense of smell have also been linked to mild cognitive impairment.

Mild cognitive impairment causes

There’s no single cause of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), just as there’s no single outcome for the disorder. Symptoms of MCI may remain stable for years, progress to Alzheimer’s disease or another type of dementia, or improve over time.

Current evidence indicates that mild cognitive impairment (MCI) often, but not always, develops from a lesser degree of the same types of brain changes seen in Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia. Some of these changes have been identified in autopsy studies of people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). These changes include:

- Abnormal clumps of beta-amyloid protein (plaques) and microscopic protein clumps of tau characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease (tangles)

- Lewy bodies, which are microscopic clumps of another protein associated with Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and some cases of Alzheimer’s disease

- Small strokes or reduced blood flow through brain blood vessels

Brain-imaging studies show that the following changes may be associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI):

- Shrinkage of the hippocampus, a brain region important for memory

- Enlargement of the brain’s fluid-filled spaces (ventricles)

- Reduced use of glucose, the sugar that’s the primary source of energy for cells, in key brain regions

Risk factors for developing mild cognitive impairment

The strongest risk factors for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) are:

- Increasing age

- Having a specific form of a gene known as APOE e4, also linked to Alzheimer’s disease — though having the gene doesn’t guarantee that you’ll experience cognitive decline

Other medical conditions and lifestyle factors have been linked to an increased risk of cognitive change, including:

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- High blood pressure

- Elevated cholesterol

- Obesity

- Depression

- Lack of physical exercise

- Low education level

- Infrequent participation in mentally or socially stimulating activities

Mild cognitive impairment prevention

Mild cognitive impairment can’t always be prevented. But research has found some environmental factors that may affect the risk of developing the condition. Studies show that these steps may help prevent cognitive impairment:

- Avoid excessive alcohol use.

- Limit exposure to air pollution.

- Reduce your risk of head injury.

- Don’t smoke.

- Manage health conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity and depression.

- Practice good sleep hygiene and manage sleep disturbances.

- Eat a nutrient-rich diet that has plenty of fruits and vegetables and is low in saturated fats.

- Engage socially with others.

- Exercise regularly at a moderate to vigorous intensity.

- Wear a hearing aid if you have hearing loss.

- Stimulate your mind with puzzles, games and memory training.

Mild Cognitive Impairment diagnosis

There is no specific test to confirm a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Your doctor will decide whether mild cognitive impairment is the most likely cause of your symptoms based on the information you provide and results of various tests that can help clarify the diagnosis.

Many doctors diagnose mild cognitive impairment based on the following criteria developed by a panel of international experts:

- You have problems with memory or another mental function. You may have problems with your memory, planning, following instructions or making decisions. Your own impressions should be confirmed by someone close to you.

- You’ve declined over time. A careful medical history reveals that your mental function has declined from a higher level. This change ideally is confirmed by a family member or a close friend.

- Your overall mental function and daily activities aren’t affected. Your medical history shows that overall your daily activities generally aren’t impaired, although specific symptoms may cause worry and inconvenience.

- Mental status testing shows a mild level of impairment for your age and education level. Doctors often assess mental performance with a brief test such as the Short Test of Mental Status, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). More-detailed neuropsychological testing may help determine the degree of memory impairment, which types of memory are most affected and whether other mental skills also are impaired.

- Your diagnosis isn’t dementia. The problems that you describe and that your doctor documents through corroborating reports, your medical history, and mental status testing aren’t severe enough to be diagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease or another type of dementia.

Neurological exam

As part of your physical exam, your doctor may perform some basic tests that indicate how well your brain and nervous system are working. These tests can help detect neurological signs of Parkinson’s disease, strokes, tumors or other medical conditions that can impair your memory as well as your physical function. The neurological exam may test:

- Reflexes

- Eye movements

- Walking and balance

Lab tests

Blood tests can help rule out physical problems that can affect memory, such as a vitamin B-12 deficiency or an underactive thyroid gland.

Brain imaging

Your doctor may order an MRI or CT scan to check for evidence of a brain tumor, stroke or bleeding.

Mental status testing

Short forms of mental status testing can be done in about 10 minutes. During testing, doctors ask people to conduct several specific tasks and answer several questions, such as naming today’s date or following a written instruction.

Longer forms of neuropsychological testing can provide additional details about your mental function compared with the function of others of a similar age and education level. These tests may also help identify patterns of change that offer clues about the underlying cause of your symptoms.

Mild cognitive impairment treatment

Currently, no mild cognitive impairment (MCI) drugs or other treatments are specifically approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, mild cognitive impairment is an active area of research. Clinical studies are underway to shed more light on the disorder and find treatments that may improve symptoms or prevent or delay progression to dementia.

Experts recommend that a person diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment be re-evaluated every six months to determine if symptoms are staying the same, improving or growing worse.

Mild cognitive impairment increases the risk of later developing dementia, but some people with mild cognitive impairment never get worse. Others with mild cognitive impairment later have test results that return to normal for their age and education.

Alzheimer’s drugs

Doctors sometimes prescribe cholinesterase inhibitors – donepezil (Aricept), a type of drug approved for Alzheimer’s disease, for people with mild cognitive impairment whose main symptom is memory loss. However, cholinesterase inhibitors aren’t recommended for routine treatment of mild cognitive impairment. Results of a large, federally funded trial showed that 10 milligrams of donepezil (Aricept) daily reduced the risk of progressing from amnestic mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease for about a year, but the benefit disappeared within three years. The study’s principal investigators said the results were not strong enough to clearly recommend donepezil as a treatment for mild cognitive impairment. However, it might be reasonable for patients and their physicians to talk about the possible benefits and risks of such treatment on an individual basis.

Treating other conditions that can affect mental function

Other common conditions besides mild cognitive impairment can make you feel forgetful or less mentally sharp than usual. Treating these conditions can help improve your memory and overall mental function. Conditions that can affect memory include:

- High blood pressure. People with mild cognitive impairment tend to be more likely to have problems with the blood vessels inside their brains. High blood pressure can worsen these problems and cause memory difficulties. Your doctor will monitor your blood pressure and recommend steps to lower it if it’s too high.

- Depression. When you’re depressed, you often feel forgetful and mentally “foggy.” Depression is common in people with mild cognitive impairment. Treating depression may help improve memory, while making it easier to cope with the changes in your life.

- Sleep apnea. In this condition, your breathing repeatedly stops and starts while you’re asleep, making it difficult to get a good night’s rest. Sleep apnea can make you feel excessively tired during the day, forgetful and unable to concentrate. Treatment can improve these symptoms and restore alertness.

Home remedies

Study results have been mixed about whether diet, exercise or other healthy lifestyle choices can prevent or reverse cognitive decline. Regardless, these healthy choices promote good overall health and may play a role in good cognitive health.

- Regular physical exercise has known benefits for heart health and may also help prevent or slow cognitive decline.

- A diet low in fat and rich in fruits and vegetables is another heart-healthy choice that also may help protect cognitive health.

- Omega-3 fatty acids also are good for the heart. Most research showing a possible benefit for cognitive health uses fish consumption as a yardstick for the amount of omega-3 fatty acids eaten.

- Intellectual stimulation may prevent cognitive decline. Studies have shown computer use, playing games, reading books and other intellectual activities may help preserve function and prevent cognitive decline.

- Social engagement may make life more satisfying, and help preserve mental function and slow mental decline.

- Memory training and other thinking (cognitive) training may help improve your function.

There is some evidence of a possible benefit on mild cognitive impairment from non-pharmacological interventions, such as cognitive training and physical exercise, activities that may be neuroprotective or compensatory. A recent review showed how several studies demonstrated the efficacy of cognitive training in mild cognitive impairment measured as improved performances in tests of global cognitive functioning, memory and meta-memory 10. A limitation of these findings is the small sample sizes of the individual studies. Only seven randomized control trials were identified by a systematic review 11, with a total of 296 mild cognitive impairment subjects who were cognitively treated. Most of these studies in fact included samples of fewer than 50 individuals; therefore, replication of the findings in larger randomized control trials is warranted.

A rapidly growing body of evidence suggests that exercise, specifically aerobic exercise, may attenuate cognitive impairment 12. A systematic review of the effect of aerobic exercise on cognitive performance in individuals with neurological disorders found modest improvements in attention and processing speed, executive function and memory 13. Therefore, as for the case of cognitive training, larger randomized control trials specifically in subjects with mild cognitive impairment, are warranted to confirm or refute these preliminary results. In particular, there is a strong need for evidence regarding the combined effect of multiple non-pharmacological interventions on mild cognitive impairment evolution and ongoing multidomain randomized control trials of mild cognitive impairment are particularly relevant 14. A further possibility is to combine pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions and evaluate whether their joint effect has more therapeutic value than the individual treatments alone. Such studies could also be combined with therapeutic trials.

Alternative medicine

Some supplements — including vitamin E, ginkgo and others — have been purported to help prevent or delay the progression of mild cognitive impairment. However, no supplement has shown any benefit in a clinical trial.

Dementia causes

Dementia symptoms can be caused by a number of conditions and each has its own causes.

The most common types of dementia symptoms are caused by 15 :

- Alzheimer’s disease,

- Vascular dementia and vascular cognitive impairment (to learn more about Vascular Dementia),

- Parkinson’s disease (to learn more about Parkinson’s Disease Dementia),

- Dementia with Lewy bodies (to learn more about Lewy Body Dementia),

- Fronto Temporal Lobar Degeneration (to learn more about Frontotemporal dementia),

- Huntington’s disease,

- Alcohol related dementia (Korsakoff’s syndrome),

- HIV Associated Dementia (AIDS Dementia Complex),

- Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease and

- Mixed dementia, a combination of two or more disorders, at least one of which is dementia 16.

Dementia risk factors

Many factors can eventually contribute to dementia. Some factors, such as age, can’t be changed. Others can be addressed to reduce your risk.

Risk factors that can’t be changed

- Age. The risk rises as you age, especially after age 65. However, dementia isn’t a normal part of aging, and dementia can occur in younger people.

- Family history. Having a family history of dementia puts you at greater risk of developing the condition. However, many people with a family history never develop symptoms, and many people without a family history do. There are tests to determine whether you have certain genetic mutations.

- Down syndrome. By middle age, many people with Down syndrome develop early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Risk factors you can change

You might be able to control the following risk factors for dementia.

- Diet and exercise. Research shows that lack of exercise increases the risk of dementia. And while no specific diet is known to reduce dementia risk, research indicates a greater incidence of dementia in people who eat an unhealthy diet compared with those who follow a Mediterranean-style diet rich in produce, whole grains, nuts and seeds.

- Excessive alcohol use. Drinking large amounts of alcohol has long been known to cause brain changes. Several large studies and reviews found that alcohol use disorders were linked to an increased risk of dementia, particularly early-onset dementia.

- Cardiovascular risk factors. These include high blood pressure (hypertension), high cholesterol, buildup of fats in your artery walls (atherosclerosis) and obesity.

- Depression. Although not yet well-understood, late-life depression might indicate the development of dementia.

- Diabetes. Having diabetes may increase your risk of dementia, especially if it’s poorly controlled.

- Smoking. Smoking might increase your risk of developing dementia and blood vessel diseases.

- Air pollution. Studies in animals have indicated that air pollution particulates can speed degeneration of the nervous system. And human studies have found that air pollution exposure — particularly from traffic exhaust and burning wood — is associated with greater dementia risk.

- Head trauma. People who’ve had a severe head trauma have a greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Several large studies found that in people age 50 years or older who had a traumatic brain injury (TBI), the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease increased. The risk increases in people with more-severe and multiple TBIs. Some studies indicate that the risk may be greatest within the first six months to two years after the TBI.

- Sleep disturbances. People who have sleep apnea and other sleep disturbances might be at higher risk of developing dementia.

- Vitamin and nutritional deficiencies. Low levels of vitamin D, vitamin B-6, vitamin B-12 and folate can increase your risk of dementia.

- Medications that can worsen memory. Try to avoid over-the-counter sleep aids that contain diphenhydramine (Advil PM, Aleve PM) and medications used to treat urinary urgency such as oxybutynin (Ditropan XL). Also limit sedatives and sleeping tablets and talk to your doctor about whether any of the drugs you take might make your memory worse.

Dementia prevention

There is no certain way to prevent all types of dementia. However, a healthy lifestyle can help lower your risk of developing dementia when you are older. It can also prevent cardiovascular diseases, such as strokes and heart attacks.

To reduce your risk of developing dementia and other serious health conditions, it’s recommended that you:

- Eat a healthy diet. A diet such as the Mediterranean diet — rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and omega-3 fatty acids, which are commonly found in certain fish and nuts — might promote health and lower your risk of developing dementia. This type of diet also improves cardiovascular health, which may help lower dementia risk.

- Get enough vitamins. Some research suggests that people with low levels of vitamin D in their blood are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. You can get vitamin D through certain foods, supplements and sun exposure. More study is needed before an increase in vitamin D intake is recommended for preventing dementia, but it’s a good idea to make sure you get adequate vitamin D. Taking a daily B-complex vitamin and vitamin C also might help.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Lose weight if you’re overweight.

- Exercise regularly. Physical activity and social interaction might delay the onset of dementia and reduce its symptoms. Aim for 150 minutes of exercise a week.

- Keep your mind active. Mentally stimulating activities, such as reading, solving puzzles and playing word games, and memory training might delay the onset of dementia and decrease its effects.

- Don’t drink too much alcohol

- Stop smoking (if you smoke). Some studies have shown that smoking in middle age and beyond might increase your risk of dementia and blood vessel conditions. Quitting smoking might reduce your risk and will improve your health.

- Make sure to keep your blood pressure at a healthy level. High blood pressure might lead to a higher risk of some types of dementia. More research is needed to determine whether treating high blood pressure may reduce the risk of dementia.

- Treat health conditions. See your doctor for treatment for depression or anxiety. Treat high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes.

- Treat hearing problems. People with hearing loss have a greater chance of developing cognitive decline. Early treatment of hearing loss, such as use of hearing aids, might help decrease the risk.

- Get good-quality sleep. Practice good sleep hygiene, and talk to your doctor if you snore loudly or have periods where you stop breathing or gasp during sleep.

Diet and dementia

A low-fat, high-fiber diet including plenty of fresh fruit and vegetables and wholegrains can help reduce your risk of some kinds of dementia.

Limiting the amount of salt in your diet to no more than 1.5 grams a day can also help. Too much salt will increase your blood pressure, which puts you at risk of developing some types of dementia.

High cholesterol levels may also put you at risk of developing some kinds of dementia, so try to limit the amount of food you eat that is high in saturated fat.

How weight affects dementia risk

Being overweight can increase your blood pressure, which increases your risk of getting some kinds of dementia. The risk is higher if you are obese. The most scientific way to measure your weight is to calculate your body mass index (BMI).

You can calculate your BMI using the BMI healthy weight calculator. People with a BMI of 25-30 are overweight, and those with a BMI above 30 are obese. People with a BMI of 40 or more are morbidly obese.

Exercise to reduce dementia risk

Exercising regularly will make your heart and blood circulatory system more efficient. It will also help to lower your cholesterol and keep your blood pressure at a healthy level, decreasing your risk of developing some kinds of dementia.

For most people, a minimum of 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, such as cycling or fast walking, is recommended.

Alcohol and dementia

Drinking excessive amounts of alcohol will cause your blood pressure to rise, as well as raising the level of cholesterol in your blood.

Stick to the recommended limits for alcohol consumption to reduce your risk of high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease and dementia.

The recommended daily limit for alcohol consumption is three to four units of alcohol a day for men, and two to three units a day for women. A unit of alcohol is equal to about half a pint of normal-strength lager, a small glass of wine or a pub measure (25ml) of spirits.

Stopping smoking could reduce dementia risk

Smoking can cause your arteries to narrow, which can lead to a rise in your blood pressure. It also increases your risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, cancer and dementia.

Dementia signs and symptoms

Dementia is not a disease itself but it’s a term used to describe a group of symptoms affecting memory, thinking and social abilities severely enough to interfere with your daily life. Dementia is a collection of symptoms that result from damage to the brain caused by different diseases. Although dementia generally involves memory loss, memory loss has different causes. Having memory loss alone doesn’t mean you have dementia, although it’s often one of the early signs of the condition.

Dementia symptoms vary depending on the cause, but common signs and symptoms include:

Cognitive changes

- Memory loss, which is usually noticed by someone else

- Difficulty communicating or finding words

- Difficulty with visual and spatial abilities, such as getting lost while driving

- Difficulty reasoning or problem-solving

- Difficulty handling complex tasks

- Difficulty with planning and organizing

- Difficulty with coordination and motor functions

- Confusion and disorientation

Psychological changes

- Personality changes

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Inappropriate behavior

- Paranoia

- Agitation

- Hallucinations

Dementia can lead to

- Poor nutrition. Many people with dementia eventually reduce or stop eating, affecting their nutrient intake. Ultimately, they may be unable to chew and swallow.

- Pneumonia. Difficulty swallowing increases the risk of choking or aspirating food into the lungs, which can block breathing and cause pneumonia.

Inability to perform self-care tasks. As dementia progresses, it can interfere with bathing, dressing, brushing hair or teeth, using the toilet independently, and taking medications as directed. - Personal safety challenges. Some day-to-day situations can present safety issues for people with dementia, including driving, cooking, and walking and living alone.

- Death. Late-stage dementia results in coma and death, often from infection.

What is the first step to diagnose dementia?

Visiting a family doctor is often the first step for people who are experiencing changes in thinking, movement, or behavior 17. However, neurologists—doctors who specialize in disorders of the brain and nervous system—generally have the expertise needed to diagnose dementia 17. Geriatric psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, and geriatricians may also be skilled in diagnosing the condition 17.

If a specialist cannot be found in your community, ask the neurology department of the nearest medical school for a referral. A hospital affiliated with a medical school may also have a dementia or movement disorders clinic that provides expert evaluation.

Dementia diagnosis

No single test can diagnose dementia, so doctors are likely to run a number of tests that can help pinpoint the problem. To diagnose dementia, doctors first assess whether a person has an underlying treatable condition such as depression, abnormal thyroid function, normal pressure hydrocephalus, or vitamin B12 deficiency 17. Early diagnosis is important, as some causes for symptoms can be treated. In many cases, the specific type of dementia a person has may not be confirmed until after the person has died and the brain is examined.

A medical assessment for dementia generally includes:

- Patient history. Typical questions about a person’s medical and family history might include asking about whether dementia runs in the family, how and when symptoms began, changes in behavior and personality, and if the person is taking certain medications that might cause or worsen symptoms.

- Physical exam. Measuring blood pressure and other vital signs may help physicians detect conditions that might cause or occur with dementia. Such conditions may be treatable.

- Neurological tests. Assessing balance, sensory function, reflexes, vision, eye movements, and other functions helps identify conditions that may affect the diagnosis or are treatable with drugs.

Tests Used to Diagnose Dementia

These tests for dementia are mainly tests of mental abilities, blood tests and brain scans. The following procedures also may be used to diagnose dementia:

Cognitive and neuropsychological tests

These tests measure memory, problem solving, attention, counting, language skills, and other abilities related to mental functioning.

People with symptoms of dementia are often given questionnaires to help test their mental abilities, to see how severe any memory problems may be. One widely used test is called the mini mental state examination (MMSE) 18.

The mini mental state examination (MMSE) assesses a number of different mental abilities, including:

- short- and long-term memory

- attention span

- concentration

- language and communication skills

- ability to plan

- ability to understand instructions

The mini mental state examination (MMSE) is a series of exercises, each carrying a score with a maximum of 30 points. These exercises include:

- memorising a short list of objects and then repeating the list

- writing a short sentence that is grammatically correct, such as “the dog sat on the floor”

- correctly answering time-orientation questions, such as identifying the day of the week, the date or the year

The mini mental state examination (MMSE) is a 30-point test

Advantages

- Relatively quick and easy to perform

- Requires no additional equipment

- Can provide a method of monitoring deterioration over time

Disadvantages

- Biased against people with poor education due to elements of language and mathematical testing

- Bias against visually impaired

- Limited examination of visuospatial cognitive ability

- Poor sensitivity at detected mild/early dementia

The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)

Footnote: The mini mental state examination (MMSE) is not a test to diagnose dementia. However, it is useful for assessing the level of mental impairment that a person with dementia may have. Test scores may be influenced by a person’s level of education. For example, someone who cannot read or write very well may have a lower score, but they may not have dementia. Similarly, someone with a higher level of education may achieve a higher score, but still have dementia.

[Source 19 ]Laboratory tests

Blood and urine tests can help rule out possible causes of symptoms.

Blood tests (in roughly descending order of importance)

- Thyroid function tests: Rule out hypothyroidism as a cause of a dementia-like presentation

- Vitamin B12: Low levels can cause memory impairment and mood changes

- Blood glucose: Independent risk factor for dementia. Unclear if high blood sugars are direct cause. Iatrogenic hypoglycaemic episodes can also cause worsening dementia. Indeed, tightly controlled blood sugars in the elderly has a negative impact on mortality.

- Urea and electrolytes: Severe disturbances can cause cognitive impairment (e.g. renal failure and hyperuraemia). Sodium and calcium are particularly important.

- Liver function tests: Metabolic causes in liver dysfunction (e.g. hyperammonaemia in cirrhosis). Rarer causes (e.g. Wilson’s disease).

- Infective screen: FBC, ESR, CRP to look for superimposed infection as cause of confusion. HIV-associated or neurosyphilis dementia.

- Autoimmune screen: Should be considered in rapidly progressive dementia.

- Further tests: More specific tests are rarely needed. However, if there is diagnostic uncertainly they may include: serum and urinary copper and caeruloplasmin (Wilsons disease); ammonia (liver disease and inherited metabolic abnormalities); HIV; syphilis serology.

Brain scans

Brain scans are often used for diagnosing dementia once other simpler tests have ruled out other problems. They are needed to check for evidence of other possible problems that could explain a person’s symptoms, such as a major stroke or a brain tumor and other problems that can cause dementia. Scans also identify changes in the brain’s structure and function. The most common scans are:

- Computed tomography (CT) scan, which uses X-rays to produce images of the brain and other organs. A computerised tomography (CT) scan can be used to check for signs of stroke or a brain tumor. However, unlike an MRI scan, a CT scan cannot provide detailed information about the structure of the brain. The National Institute for Health recommends using a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to help confirm a diagnosis of dementia 18.CT scans are quick, painless and generally safe. However, there’s a small risk you could have an allergic reaction to the contrast dye used and you will be exposed to X-ray radiation. The amount of radiation you’re exposed to during a CT scan varies, depending on how much of your body is scanned. CT scanners are designed to make sure you’re not exposed to unnecessarily high levels. Generally, the amount of radiation you’re exposed to during each scan is the equivalent to between a few months and a few years of exposure to natural radiation from the environment.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of body structures, including tissues, organs, bones, and nerves. An MRI scan can provide detailed information about the blood vessel damage that occurs in vascular dementia, plus any shrinking of the brain. In frontotemporal dementia, the frontal and temporal lobes are mainly affected by shrinking 18. MRI scans don’t involve exposing the body to X-ray radiation. This means people who may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of radiation, such as pregnant women and babies, can use them if necessary. An MRI scan is a painless and safe procedure. You may find it uncomfortable if you have claustrophobia, but most people find this manageable with support from the radiographer. Extensive research has been carried out into whether the magnetic fields and radio waves used during MRI scans could pose a risk to the human body. No evidence has been found to suggest there’s a risk, which means MRI scans are one of the safest medical procedures currently available. However, not everyone can have an MRI scan. For example, they’re not always possible for people who have certain types of implants fitted, such as a pacemaker (a battery-operated device that helps to control an irregular heartbeat).

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan or a single photon-emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan, which uses radiation to provide pictures of brain activity may be recommended if the result of your CT or MRI scan is uncertain. These scans look at how the brain functions and can pick up abnormalities with the blood flow in the brain. They’re particularly helpful for investigating confirmed cases of cancer, to determine how far the cancer has spread and how well it’s responding to treatment. They can also help diagnose some conditions that affect the normal workings of the brain, such as dementia. PET scanners work by detecting the radiation given off by a substance called a radiotracer as it collects in different parts of your body.In most PET scans a radiotracer called fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is used, which is similar to naturally occurring glucose (a type of sugar) so your body treats it in a similar way. Before the scan, the radiotracer is injected into a vein in your arm or hand. You will need to wait quietly for about an hour, to give it time to be absorbed by the cells in your body. By analysing the areas where the radiotracer does and doesn’t build up, it’s possible to work out how well certain body functions are working and identify any abnormalities. For example, a concentration of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in the body’s tissues can help identify cancerous cells because cancer cells use glucose at a much faster rate than normal cells.In a standard PET scan the amount of radiation you’re exposed to is small – about the same as the amount you get from natural sources, such as the sun, over three years.The radiotracer becomes quickly less radioactive over time and will usually be passed out of your body naturally within a few hours. Drinking plenty of fluid after the scan can help flush it from your body.As a precaution, you may be advised to avoid prolonged close contact with pregnant women, babies or young children for a few hours after a PET scan, as you will be slightly radioactive during this time.

- In some cases, an electroencephalogram (EEG) may be taken to record the brain’s electrical signals (brain activity).

- Psychiatric evaluation. This evaluation will help determine if depression or another mental health condition is causing or contributing to a person’s symptoms.

- Genetic tests. Some dementias are caused by a known gene defect. In these cases, a genetic test can help people know if they are at risk for dementia. People should talk with family members, a primary care doctor, and a genetic counselor before getting tested.

Dementia treatment

Most types of dementia can’t be cured, but there are ways to manage your symptoms.

Dementia medications

The following are used to temporarily improve dementia symptoms:

- Cholinesterase inhibitors. These medications — including donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon) and galantamine (Razadyne) — work by boosting levels of a chemical messenger involved in memory and judgment. Although primarily used to treat Alzheimer’s disease, these medications might also be prescribed for other dementias, including vascular dementia, Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia. Side effects can include nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Other possible side effects include slowed heart rate, fainting and sleep disturbances.

- Memantine. Memantine (Namenda) works by regulating the activity of glutamate, another chemical messenger involved in brain functions, such as learning and memory. In some cases, memantine is prescribed with a cholinesterase inhibitor. A common side effect of memantine is dizziness.

- Other medications. Your doctor might prescribe medications to treat other symptoms or conditions, such as depression, sleep disturbances, hallucinations, parkinsonism or agitation.

Dementia therapies

Several dementia symptoms and behavior problems might be treated initially using nondrug approaches, such as:

- Occupational therapy. An occupational therapist can show you how to make your home safer and teach coping behaviors. The purpose is to prevent accidents, such as falls; manage behavior and prepare you for the dementia progression.

- Modifying the environment. Reducing clutter and noise can make it easier for someone with dementia to focus and function. You might need to hide objects that can threaten safety, such as knives and car keys. Monitoring systems can alert you if the person with dementia wanders.

- Simplifying tasks. Break tasks into easier steps and focus on success, not failure. Structure and routine also help reduce confusion in people with dementia.

The following techniques may help reduce agitation and promote relaxation in people with dementia.

- Music therapy, which involves listening to soothing music

- Light exercise

- Watching videos of family members

- Pet therapy, which involves use of animals, such as visits from dogs, to promote improved moods and behaviors in people with dementia

- Aromatherapy, which uses fragrant plant oils

- Massage therapy

- Art therapy, which involves creating art, focusing on the process rather than the outcome

Alternative medicine

Several dietary supplements, herbal remedies and therapies have been studied for people with dementia. But there’s no convincing evidence for any of these. Use caution when considering taking dietary supplements, vitamins or herbal remedies, especially if you’re taking other medications. These remedies aren’t regulated, and claims about their benefits aren’t always based on scientific research.

While some studies suggest that vitamin E supplements may be helpful for Alzheimer’s disease, the results have been mixed. Also, high doses of vitamin E can pose risks. Taking vitamin E supplements is generally not recommended, but including foods high in vitamin E, such as nuts, in your diet, is.

Dementia home remedies

Dementia symptoms and behavior problems will progress over time. Caregivers and care partners might try the following suggestions:

- Enhance communication. When talking with your loved one, maintain eye contact. Speak slowly in simple sentences, and don’t rush the response. Present one idea or instruction at a time. Use gestures and cues, such as pointing to objects.

- Encourage exercise. The main benefits of exercise in people with dementia include improved strength, balance and cardiovascular health. Exercise might also help with symptoms such as restlessness. There is growing evidence that exercise also protects the brain from dementia, especially when combined with a healthy diet and treatment for risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Some research also shows that physical activity might slow the progression of impaired thinking in people with Alzheimer’s disease, and it can lessen symptoms of depression.

- Engage in activity. Plan activities the person with dementia enjoys and can do. Dancing, painting, gardening, cooking, singing and other activities can be fun, can help you connect with your loved one, and can help your loved one focus on what he or she can still do.

- Establish a nighttime ritual. Behavior is often worse at night. Try to establish going-to-bed rituals that are calming and away from the noise of television, meal cleanup and active family members. Leave night lights on in the bedroom, hall and bathroom to prevent disorientation. Limiting caffeine, discouraging napping and offering opportunities for exercise during the day might ease nighttime restlessness.

- Keep a calendar. A calendar might help your loved one remember upcoming events, daily activities and medication schedules. Consider sharing a calendar with your loved one.

- Plan for the future. Develop a plan with your loved one while he or she is able to participate that identifies goals for future care. Support groups, legal advisers, family members and others might be able to help. You’ll need to consider financial and legal issues, safety and daily living concerns, and long-term care options. See Dementia Care Plans below.

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills and eventually, the ability to carry out the simplest tasks 20. In most people with the disease—those with the late-onset type—symptoms first appear in their mid-60s. Early-onset Alzheimer’s occurs between a person’s 30s and mid-60s and is very rare. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia among older adults 21.

Alzheimer’s disease begins slowly and it usually begins after age 60 21. The risk goes up as you get older. Your risk is also higher if a family member has had the disease 21. It first involves the parts of the brain that control thought, memory and language. People with Alzheimer’s disease may have trouble remembering things that happened recently or names of people they know. A related problem, mild cognitive impairment, causes more memory problems than normal for people of the same age. Many, but not all, people with mild cognitive impairment will develop Alzheimer’s Disease 21.

In Alzheimer’s disease, over time, symptoms get worse. People may not recognize family members. They may have trouble speaking, reading or writing. They may forget how to brush their teeth or comb their hair. Later on, they may become anxious or aggressive, or wander away from home. Eventually, they need total care. This can cause great stress for family members who must care for them.

No treatment can stop the disease. However, some drugs may help keep symptoms from getting worse for a limited time.

Alzheimer’s disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer. In 1906, Dr. Alzheimer noticed changes in the brain tissue of a woman who had died of an unusual mental illness 20. Her symptoms included memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behavior. After she died, he examined her brain and found many abnormal clumps (now called amyloid plaques) and tangled bundles of fibers (now called neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles).

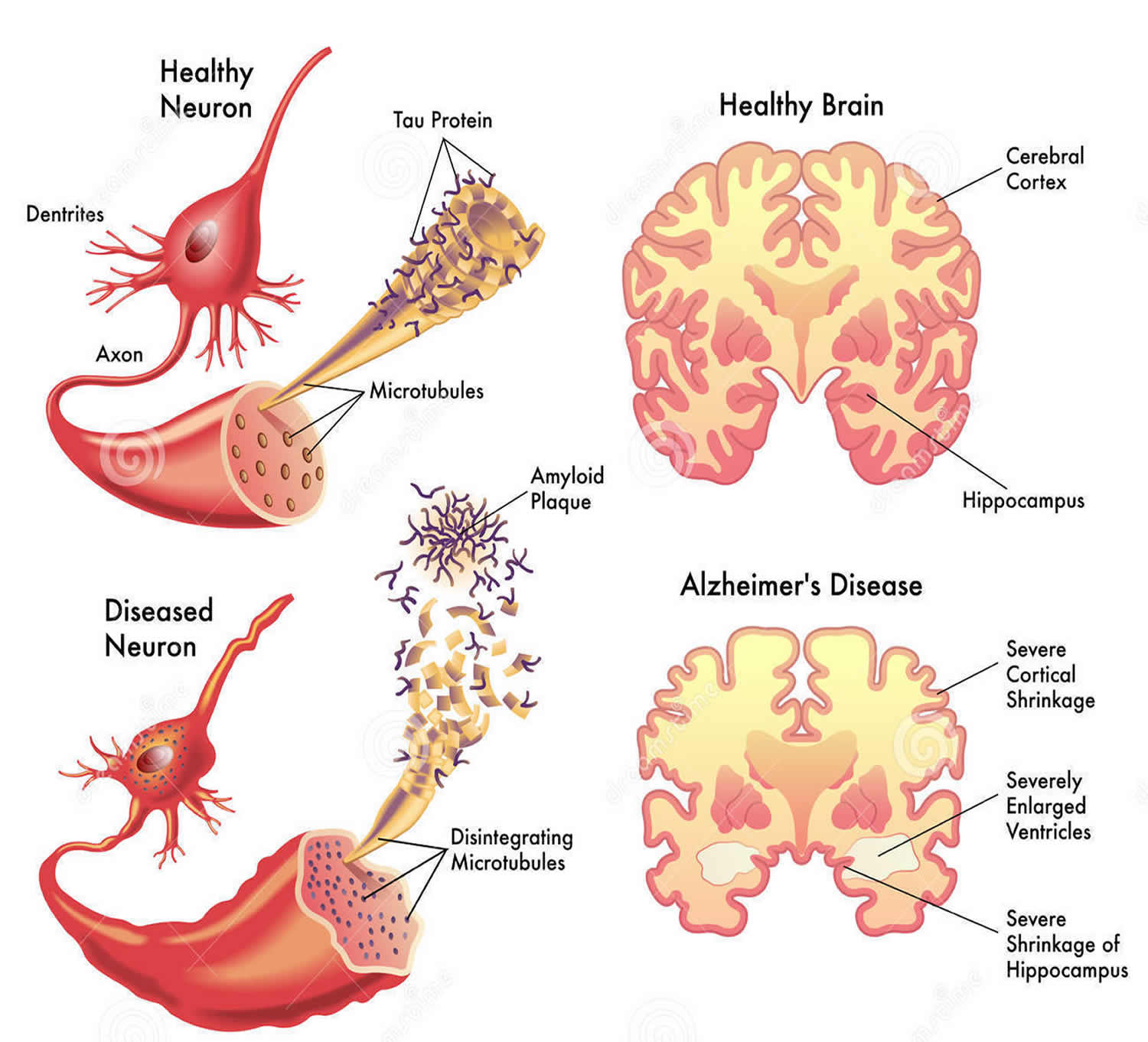

These plaques and tangles in the brain are still considered some of the main features of Alzheimer’s disease 20. Another feature is the loss of connections between nerve cells (neurons) in the brain. Neurons transmit messages between different parts of the brain and from the brain to muscles and organs in the body. Many other complex brain changes are thought to play a role in Alzheimer’s disease, too.

This damage initially appears to take place in the hippocampus, the part of the brain essential in forming memories. As neurons die, additional parts of the brain are affected. By the final stage of Alzheimer’s disease, damage is widespread, and brain tissue has shrunk significantly.

What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease?

The healthy human brain contains tens of billions of neurons—specialized cells that process and transmit information via electrical and chemical signals. They send messages between different parts of the brain, and from the brain to the muscles and organs of the body. Alzheimer’s disease disrupts this communication among neurons, resulting in loss of function and cell death.

Key Biological Processes in the Brain

Most neurons have three basic parts: a cell body, multiple dendrites, and an axon (see Figure 2).

- The cell body contains the nucleus, which houses the genetic blueprint that directs and regulates the cell’s activities.

- Dendrites are branch-like structures that extend from the cell body and collect information from other neurons.

- The axon is a cable-like structure at the end of the cell body opposite the dendrites and transmits messages to other neurons.

The function and survival of neurons depend on several key biological processes:

- Communication. Neurons are constantly in touch with neighboring brain cells. When a neuron receives signals from other neurons, it generates an electrical charge that travels down the length of its axon and releases neurotransmitter chemicals across a tiny gap, called a synapse. Like a key fitting into a lock, each neurotransmitter molecule then binds to specific receptor sites on a dendrite of a nearby neuron. This process triggers chemical or electrical signals that either stimulate or inhibit activity in the neuron receiving the signal. Communication often occurs across networks of brain cells. In fact, scientists estimate that in the brain’s communications network, one neuron may have as many as 7,000 synaptic connections with other neurons.

- Metabolism. Metabolism—the breaking down of chemicals and nutrients within a cell—is critical to healthy cell function and survival. To perform this function, cells require energy in the form of oxygen and glucose, which are supplied by blood circulating through the brain. The brain has one of the richest blood supplies of any organ and consumes up to 20 percent of the energy used by the human body—more than any other organ.

- Repair, remodeling, and regeneration. Unlike many cells in the body, which are relatively short-lived, neurons have evolved to live a long time—more than 100 years in humans. As a result, neurons must constantly maintain and repair themselves. Neurons also continuously adjust, or “remodel,” their synaptic connections depending on how much stimulation they receive from other neurons. For example, they may strengthen or weaken synaptic connections, or even break down connections with one group of neurons and build new connections with a different group. Adult brains may even generate new neurons—a process called neurogenesis. Remodeling of synaptic connections and neurogenesis are important for learning, memory, and possibly brain repair.

Neurons are a major player in the central nervous system, but other cell types are also key to healthy brain function. In fact, glial cells are by far the most numerous cells in the brain, outnumbering neurons by about 10 to 1 (see Figure 3). These cells, which come in various forms—such as microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes—surround and support the function and healthy of neurons. For example, microglia protect neurons from physical and chemical damage and are responsible for clearing foreign substances and cellular debris from the brain. To carry out these functions, glial cells often collaborate with blood vessels in the brain. Together, glial and blood vessel cells regulate the delicate balance within the brain to ensure that it functions at its best.

Figure 1. Alzheimer’s disease brain

Figure 2. Alzheimer’s disease brain with amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary or tau, tangles

Figure 3. Glial (neuroglial) cells in the brain (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglial cells)

Footnote: Glial (Neuroglial) cells do not conduct nerve impulses, but, instead, support, nourish, and protect the neurons. Glial cells (glia) are far more numerous than neurons and, unlike neurons, are capable of mitosis. Glial roles that are well-established include maintaining the ionic milieu of nerve cells, modulating the rate of nerve signal propagation, modulating synaptic action by controlling the uptake of neurotransmitters, providing a scaffold for some aspects of neural development, and aiding in (or preventing, in some instances) recovery from neural injury.

[Source 22 ]How Does Alzheimer’s Disease Affect the Brain?

The brain typically shrinks to some degree in healthy aging but, surprisingly, does not lose neurons in large numbers. In Alzheimer’s disease, however, damage is widespread, as many neurons stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and die. Alzheimer’s disrupts processes vital to neurons and their networks, including communication, metabolism, and repair 23.

At first, Alzheimer’s disease typically destroys neurons and their connections in parts of the brain involved in memory, including the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. It later affects areas in the cerebral cortex responsible for language, reasoning, and social behavior. Eventually, many other areas of the brain are damaged. Over time, a person with Alzheimer’s gradually loses his or her ability to live and function independently. Ultimately, the disease is fatal 23.

Figure 4. Brain showing Entorhinal cortex (parahippocampal gyrus) and Hippocampus

What are the main characteristics of the brain with Alzheimer’s disease?

Many molecular and cellular changes take place in the brain of a person with Alzheimer’s disease. These changes can be observed in brain tissue under the microscope after death. Investigations are underway to determine which changes may cause Alzheimer’s and which may be a result of the disease.

Amyloid Plaques

The beta-amyloid protein involved in Alzheimer’s comes in several different molecular forms that collect between neurons. It is formed from the breakdown of a larger protein, called amyloid precursor protein. One form, beta-amyloid 42, is thought to be especially toxic. In the Alzheimer’s brain, abnormal levels of this naturally occurring protein clump together to form plaques that collect between neurons and disrupt cell function. Research is ongoing to better understand how, and at what stage of the disease, the various forms of beta-amyloid influence Alzheimer’s.

Neurofibrillary Tangles

Neurofibrillary tangles are abnormal accumulations of a protein called tau that collect inside neurons. Healthy neurons, in part, are supported internally by structures called microtubules, which help guide nutrients and molecules from the cell body to the axon and dendrites. In healthy neurons, tau normally binds to and stabilizes microtubules. In Alzheimer’s disease, however, abnormal chemical changes cause tau to detach from microtubules and stick to other tau molecules, forming threads that eventually join to form tangles inside neurons. These tangles block the neuron’s transport system, which harms the synaptic communication between neurons.

Emerging evidence suggests that Alzheimer’s-related brain changes may result from a complex interplay among abnormal tau and beta-amyloid proteins and several other factors. It appears that abnormal tau accumulates in specific brain regions involved in memory. Beta-amyloid clumps into plaques between neurons. As the level of beta-amyloid reaches a tipping point, there is a rapid spread of tau throughout the brain.

Chronic Inflammation

Research suggests that chronic inflammation may be caused by the buildup of glial cells normally meant to help keep the brain free of debris. One type of glial cell, microglia, engulfs and destroys waste and toxins in a healthy brain. In Alzheimer’s, microglia fail to clear away waste, debris, and protein collections, including beta-amyloid plaques. Researchers are trying to find out why microglia fail to perform this vital function in Alzheimer’s.

One focus of study is a gene called TREM2. Normally, TREM2 tells the microglia cells to clear beta-amyloid plaques from the brain and helps fight inflammation in the brain. In the brains of people where this gene does not function normally, plaques build up between neurons. Astrocytes—another type of glial cell—are signaled to help clear the buildup of plaques and other cellular debris left behind. These microglia and astrocytes collect around the neurons but fail to perform their debris-clearing function. In addition, they release chemicals that cause chronic inflammation and further damage the neurons they are meant to protect.

Vascular Contributions to Alzheimer’s Disease

People with dementia seldom have only Alzheimer’s-related changes in their brains. Any number of vascular issues—problems that affect blood vessels, such as beta-amyloid deposits in brain arteries, atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), and mini-strokes—may also be at play.

Vascular problems may lead to reduced blood flow and oxygen to the brain, as well as a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, which usually protects the brain from harmful agents while allowing in glucose and other necessary factors. In a person with Alzheimer’s, a faulty blood-brain barrier prevents glucose from reaching the brain and prevents the clearing away of toxic beta-amyloid and tau proteins. This results in inflammation, which adds to vascular problems in the brain. Because it appears that Alzheimer’s is both a cause and consequence of vascular problems in the brain, researchers are seeking interventions to disrupt this complicated and destructive cycle.

Loss of Neuronal Connections and Cell Death

In Alzheimer’s disease, as neurons are injured and die throughout the brain, connections between networks of neurons may break down, and many brain regions begin to shrink. By the final stages of Alzheimer’s, this process—called brain atrophy—is widespread, causing significant loss of brain volume.

How many Americans have Alzheimer’s disease?

Estimates vary, but experts suggest that more than 5 million Americans may have Alzheimer’s 20. Unless the disease can be effectively treated or prevented, the number of people with it will increase significantly if current population trends continue. This is because increasing age is the most important known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease 20.

What does Alzheimer’s disease look like?

Memory problems are typically one of the first signs of Alzheimer’s, though initial symptoms may vary from person to person. A decline in other aspects of thinking, such as finding the right words, vision/spatial issues, and impaired reasoning or judgment, may also signal the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Mild cognitive impairment is a condition that can be an early sign of Alzheimer’s, but not everyone with mild cognitive impairment will develop the disease.

People with Alzheimer’s have trouble doing everyday things like driving a car, cooking a meal, or paying bills. They may ask the same questions over and over, get lost easily, lose things or put them in odd places, and find even simple things confusing. As the disease progresses, some people become worried, angry, or violent. Later on, they may become anxious or aggressive, or wander away from home. Eventually, they need total care. This can cause great stress for family members who must care for them.

No treatment can stop the disease. However, some drugs may help keep symptoms from getting worse for a limited time.

How long can a person live with Alzheimer’s disease?

The time from diagnosis to death varies—as little as 3 or 4 years if the person is older than 80 when diagnosed, to as long as 10 or more years if the person is younger 20.

Alzheimer’s disease is currently ranked as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, but recent estimates indicate that the disorder may rank third, just behind heart disease and cancer, as a cause of death for older people 20.

Although treatment can help manage symptoms in some people, currently there is no cure for this devastating disease 20.

Alzheimer’s disease causes

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks 24.

Scientists believe that many factors influence when Alzheimer’s disease begins and how it progresses.

Increasing age is the most important known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease 24. The number of people with the disease doubles every 5 years beyond age 65. About one-third of all people age 85 and older may have Alzheimer’s disease 24.

The causes of late-onset Alzheimer’s, the most common form of the disease, probably include a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors 24. The importance of any one of these factors in increasing or decreasing the risk of development Alzheimer’s may differ from person to person.

Scientists are learning how age-related changes in the brain may harm nerve cells and contribute to Alzheimer’s damage. These age-related changes include atrophy (shrinking) of certain parts of the brain, inflammation, production of unstable molecules called free radicals, and breakdown of energy production within cells.

As scientists learn more about this devastating disease, they realize that genes also play an important role.

Each human cell contains the instructions a cell needs to do its job. These instructions are made up of DNA, which is packed tightly into structures called chromosomes. Each chromosome has thousands of segments called genes.

Genes are passed down from a person’s birth parents. They carry information that defines traits such as eye color and height. Genes also play a role in keeping the body’s cells healthy. Problems with genes—even small changes to a gene—can cause diseases like Alzheimer’s disease.

Figure 5. Genes

Figure 6. Genes (DNA) come from Chromosomes that reside inside your cells nucleus

Some diseases are caused by a genetic mutation, or permanent change in one or more specific genes. If a person inherits from a parent a genetic mutation that causes a certain disease, then he or she will usually get the disease. Sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, and early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease are examples of inherited genetic disorders.

In other diseases, a genetic variant may occur. A single gene can have many variants. Sometimes, this difference in a gene can cause a disease directly. More often, a variant plays a role in increasing or decreasing a person’s risk of developing a disease or condition. When a genetic variant increases disease risk but does not directly cause a disease, it is called a genetic risk factor.

Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics

There are two types of Alzheimer’s—early-onset and late-onset. Both types have a genetic component.

Table 1. Some differences between Late-Onset and Early-Onset Alzheimer’s disease

| Late-Onset Alzheimer’s | Early-Onset Alzheimer’s |

|---|---|

| Signs first appear in a person’s mid-60s | Signs first appear between a person’s 30s and mid-60s |

| Most common type (over 90% of Alzheimer’s) | Very rare (under 10% of Alzheimer’s) |

| May involve a gene called APOE ɛ4 | Usually caused by gene changes passed down from parent to child |

Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease

Most people with Alzheimer’s disease have the late-onset form of the disease, in which symptoms become apparent in the mid-60s.

Researchers have not found a specific gene that directly causes the late-onset form of the disease 24. However, one genetic risk factor—having one form of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene on chromosome 19—does increase a person’s risk. APOE comes in several different forms, or alleles:

- APOE ɛ2 is relatively rare and may provide some protection against the disease. If Alzheimer’s disease occurs in a person with this allele, it usually develops later in life than it would in someone with the APOE ɛ4 gene.

- APOE ɛ3, the most common allele, is believed to play a neutral role in the disease—neither decreasing nor increasing risk.

- APOE ɛ4 increases risk for Alzheimer’s disease and is also associated with an earlier age of disease onset. A person has zero, one, or two APOE ɛ4 alleles. Having more APOE ɛ4 alleles increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

APOE ɛ4 is called a risk-factor gene because it increases a person’s risk of developing the disease. However, inheriting an APOE ɛ4 allele does not mean that a person will definitely develop Alzheimer’s disease. Some people with an APOE ɛ4 allele never get the disease, and others who develop Alzheimer’s disease do not have any APOE ɛ4 alleles.

Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease

Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease occurs between a person’s 30s to mid-60s and represents less than 10 percent of all people with Alzheimer’s disease 24. Some cases are caused by an inherited change in one of three genes, resulting in a type known as early-onset Familial Alzheimer’s disease. For other cases of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, research suggests there may be a genetic component related to factors other than these three genes.

A child whose biological mother or father carries a genetic mutation for early-onset Familial Alzheimer’s disease has a 50/50 chance of inheriting that mutation. If the mutation is in fact inherited, the child has a very strong probability of developing early-onset Familial Alzheimer’s disease.

Early-onset Familial Alzheimer’s disease is caused by any one of a number of different single gene mutations on chromosomes 21, 14, and 1 24. Each of these mutations causes abnormal proteins to be formed. Mutations on chromosome 21 cause the formation of abnormal amyloid precursor protein (APP) 24. A mutation on chromosome 14 causes abnormal presenilin 1 to be made, and a mutation on chromosome 1 leads to abnormal presenilin 2 24.

Each of these mutations plays a role in the breakdown of APP, a protein whose precise function is not yet fully understood. This breakdown is part of a process that generates harmful forms of amyloid plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

Health, Environmental, and Lifestyle Factors

Research suggests that a host of factors beyond genetics may play a role in the development and course of Alzheimer’s disease. There is a great deal of interest, for example, in the relationship between cognitive decline and vascular conditions such as heart disease, stroke, and high blood pressure, as well as metabolic conditions such as diabetes and obesity. Ongoing research will help us understand whether and how reducing risk factors for these conditions may also reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s.

A nutritious diet, physical activity, social engagement, and mentally stimulating pursuits have all been associated with helping people stay healthy as they age. These factors might also help reduce the risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical trials are testing some of these possibilities.

Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis

Doctors use several methods and tools to help determine whether a person who is having memory problems has “possible Alzheimer’s dementia” (dementia may be due to another cause), “probable Alzheimer’s dementia” (no other cause for dementia can be found), or some other problem 25.

To diagnose Alzheimer’s, doctors may 25:

- Ask the person and a family member or friend questions about overall health, use of prescription and over-the-counter medicines, diet, past medical problems, ability to carry out daily activities, and changes in behavior and personality

- Conduct tests of memory, problem solving, attention, counting, and language

- Carry out standard medical tests, such as blood and urine tests, to identify other possible causes of the problem

- Perform brain scans, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET), to rule out other possible causes for symptoms

These tests may be repeated to give doctors information about how the person’s memory and other cognitive functions are changing over time. They can also help diagnose other causes of memory problems, such as stroke, tumor, Parkinson’s disease, sleep disturbances, side effects of medication, an infection, mild cognitive impairment, or a non-Alzheimer’s dementia, including vascular dementia. Some of these conditions may be treatable and possibly reversible.

People with memory problems should return to the doctor every 6 to 12 months 25.

- It’s important to note that Alzheimer’s disease can be definitively diagnosed only after death, by linking clinical measures with an examination of brain tissue in an autopsy 25.

What Happens Next?

If a primary care doctor suspects mild cognitive impairment or possible Alzheimer’s, he or she may refer the patient to a specialist who can provide a detailed diagnosis or further assessment. Specialists include:

- Geriatricians, who manage health care in older adults and know how the body changes as it ages and whether symptoms indicate a serious problem

- Geriatric psychiatrists, who specialize in the mental and emotional problems of older adults and can assess memory and thinking problems

- Neurologists, who specialize in abnormalities of the brain and central nervous system and can conduct and review brain scans

- Neuropsychologists, who can conduct tests of memory and thinking

Memory clinics and centers, including Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers, offer teams of specialists who work together to diagnose the problem. Tests often are done at the clinic or center, which can speed up diagnosis.

What are the benefits of Early Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis?

Early, accurate diagnosis is beneficial for several reasons. Beginning treatment early in the disease process may help preserve daily functioning for some time, even though the underlying Alzheimer’s process cannot be stopped or reversed.

Having an early diagnosis helps people with Alzheimer’s Disease and their families:

- Plan for the future

- Take care of financial and legal matters

- Address potential safety issues

- Learn about living arrangements

- Develop support networks

In addition, an early diagnosis gives people greater opportunities to participate in clinical trials that are testing possible new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease or in other research studies.

Alzheimer’s disease treatment

Alzheimer’s disease is complex, and it is unlikely that any one drug or other intervention will successfully treat it 26. Current approaches focus on helping people maintain mental function, manage behavioral symptoms, and slow or delay the symptoms of disease.

Several prescription drugs are currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat people who have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Treating the symptoms of Alzheimer’s can provide patients with comfort, dignity, and independence for a longer period of time and can encourage and assist their caregivers as well.

Most medicines work best for people in the early or middle stages of Alzheimer’s. For example, they can keep memory loss from getting worse over time. It is important to understand that none of these medications stops the disease itself.

Treatment for Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s disease

Medications called cholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. These drugs may help delay or prevent symptoms from becoming worse for a limited time and may help control some behavioral symptoms. The medications are Razadyne® (galantamine), Exelon® (rivastigmine), and Aricept® (donepezil) 26.