Zika fever

Zika fever also called Zika, Zika fever or Zika virus disease, is a viral infection caused by Zika virus that is spread mostly by the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito (Aedes aegypti mosquito and Aedes albopictus mosquito). These are the same mosquitoes that spread dengue and chikungunya viruses. These mosquitoes bite during the day and night. The Zika virus is most often spread to people through Aedes aegypti mosquito bites, primarily in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. Four out of five people who are infected with the Zika virus have no signs and symptoms. Those who do have symptoms usually have mild flu-like illness with mild fever, rash (maculopapulous eruption), conjunctivitis (“pink eye”), joint pain (arthralgia) and/or muscle pain (myalgia) 1. In rare cases, the Zika virus may cause brain or nervous system complications, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, even in people who never show symptoms of infection. Symptoms can begin 3-7 days after being infected and can last for several days to a week. A person with Zika fever can treat the symptoms, but there is no cure or vaccine for Zika virus disease. Even if an infected person treats their symptoms, or even if they do not have symptoms, they can still pass the Zika virus to others through sex or to a developing baby in pregnancy.

Women who are infected with the Zika virus during pregnancy have an increased risk of miscarriage. Zika virus infection during pregnancy also increases the risk of serious birth defects in infants, including a potentially fatal brain condition called microcephaly and other severe fetal brain defects 2.

Zika virus infection diagnosis is established by detection of viral RNA by Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) 1.

Researchers are working on a vaccine for the Zika virus. For now, the best way to prevent infection is to avoid mosquito bites and reduce mosquito habitats.

Zika virus was discovered in Uganda in 1947. It’s a type of virus called a flavivirus. Other flaviviruses include dengue, yellow fever, and West Nile viruses. Like its relatives, Zika virus is mainly transmitted to humans through the bite of infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Most people infected with Zika virus don’t get sick. The 20% or so who do tend to have mild symptoms that subside within a week. Symptoms can include fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (pink eye).

Zika virus circulated relatively unnoticed in areas of Africa and Southeast Asia until 2007, when it caused an outbreak in a new region, Yap Island in Micronesia. In 2013, the virus caused an outbreak in French Polynesia. The first confirmed case of infection in Brazil came in May 2015. Since that time, the virus has spread to other countries and territories in Central and South America as well as the Caribbean, including Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The current outbreak provides mounting evidence that Zika virus can also cause a serious birth defect called microcephaly in babies born to mothers infected with the virus during pregnancy. Microcephaly is a condition marked by an unusually small head, brain damage, and developmental delays.

There is no specific treatment for infection with the Zika virus. To help relieve symptoms, get plenty of rest and drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration. The over-the-counter (OTC) medication acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) may help relieve joint pain and fever.

The symptoms of Zika virus infection are similar to other mosquito-borne illnesses, such as dengue fever. If you’re feeling ill after recent travel to an area where mosquito-borne illness is common, see your doctor. Don’t take ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve) or aspirin until your doctor has ruled out dengue fever. These medications can increase the risk of serious complications from dengue fever.

Zika fever key facts 3:

- There is no current local transmission of Zika virus in the continental United States.

- The last cases of local Zika transmission by mosquitoes in the continental United States were in Florida and Texas in 2016-17.

- Since 2019, there have been no confirmed Zika virus disease cases reported from United States territories.

- No Zika virus transmission by mosquitoes has ever been reported in Alaska and Hawaii.

Figure 1. Aedes aegypti mosquito

Figure 2. Aedes albopictus mosquito also known as the Asian tiger mosquito or Forest day mosquito

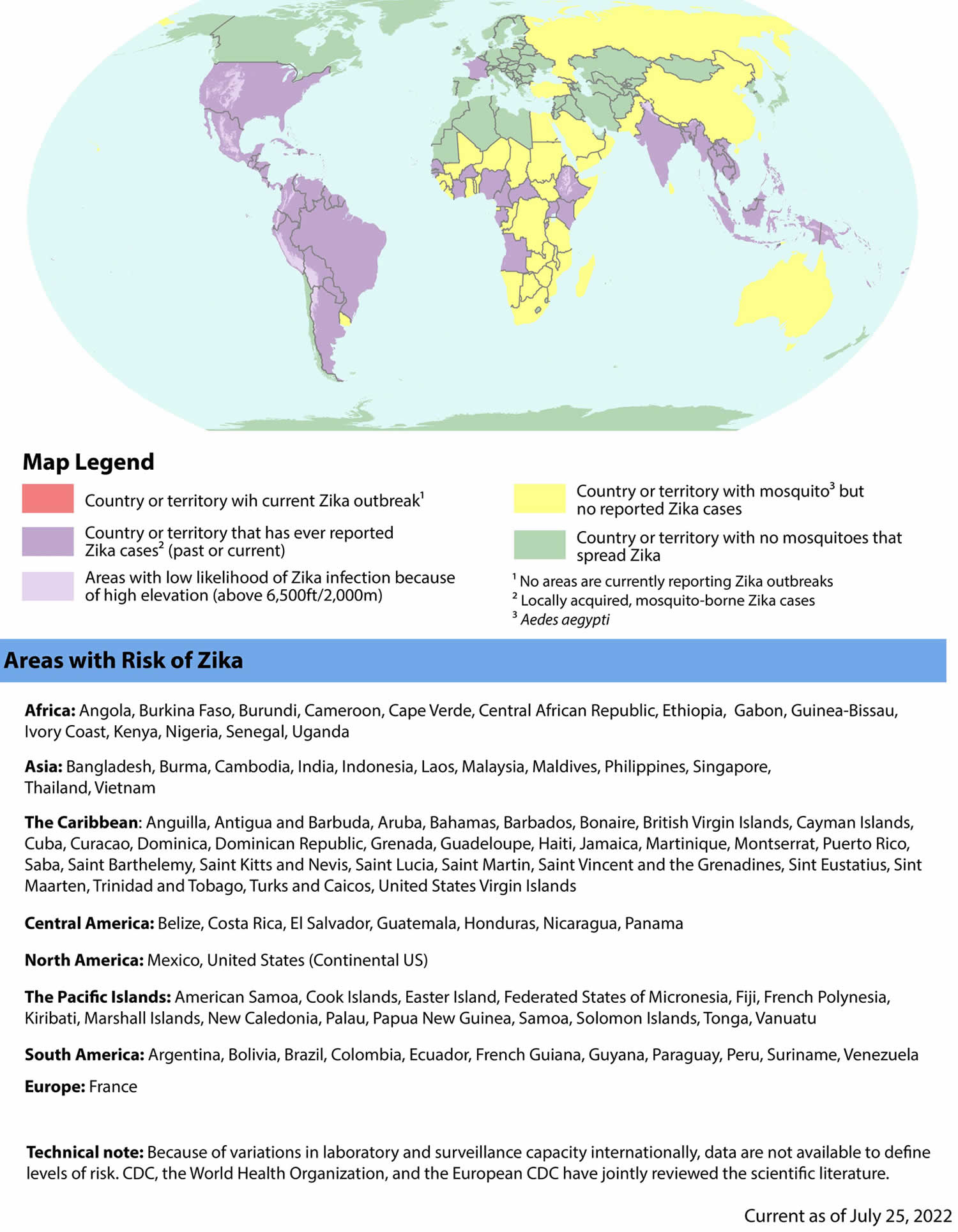

Figure 3. Areas with risk of Zika fever

Footnotes:

Areas with Zika outbreaks (red areas): Areas with current or past transmission but no Zika outbreak (purple areas): American Samoa, Angola, Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Aruba, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Bonaire, Brazil, British Virgin Islands, Burkina Faso, Burma, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Cayman Islands, Central African Republic, Colombia, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Cuba, Curacao, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Easter Island, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, France, French Guiana, French Polynesia, Gabon, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Kenya, Kiribati, Laos, Malaysia, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Martinique, Mexico, Montserrat, New Caledonia, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Palau, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Puerto Rico, Saba, Saint Barthelemy, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Martin, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Senegal, Singapore, Sint Eustatius, Sint Maarten, Solomon Islands, Suriname, Thailand, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos, Uganda, United States (Continental US), United States Virgin Islands, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam

Areas with mosquitoes but no reported Zika cases (yellow areas): Australia, Benin, Bhutan, Botswana, Brunei, Chad, China, Christmas Island, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, East Timor, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Georgia, Ghana, Guam, Guinea, Liberia, Madagascar, Madeira Islands, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Nauru, Nepal, Niger, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Oman, Pakistan, Russia, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Taiwan, Tanzania, The Gambia, Togo, Tokelau, Turkey, Tuvalu, Uruguay, Wallis and Futuna, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe

Areas with no mosquitoes that spread Zika (green areas): Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Azores, Bahrain, Belarus, Belgium, Bermuda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, British Indian Ocean Territory, Bulgaria, Canada, Canary Islands, Chile, Cocos Islands, Comoros, Corsica, Croatia, Crozet Islands, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Eswatini, Falkland Islands, Faroe Islands, Finland, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Greenland, Guernsey, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Isle of Man, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jersey, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kerguelen Islands, Kosovo, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lebanon, Lesotho, Libya, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macau, Malta, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mayotte, Moldova, Monaco, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norfolk Island, North Korea, North Macedonia, Norway, Pitcairn Islands, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Reunion, Romania, Saint Helena, Saint Paul and New Amsterdam Islands, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, San Marino, São Tomé and Principe, Serbia, Seychelles, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Uzbekistan, Vatican City, Wake Island, Western Sahara

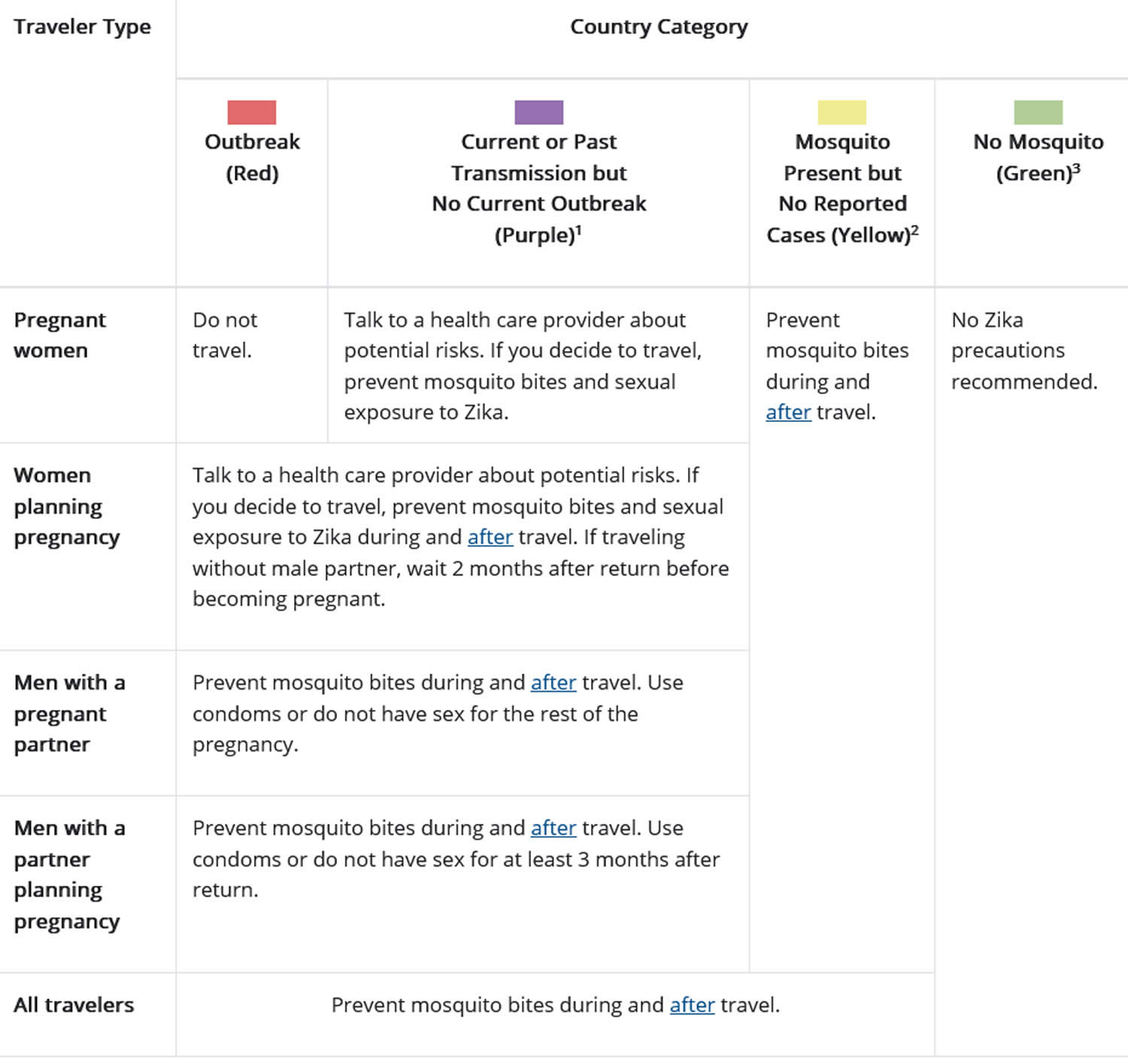

[Source 4 ]Table 1. CDC Zika Recommendations for US Residents Traveling Abroad

Footnotes:

1 These countries have a potential risk of Zika, but we do not have accurate information on the current level of risk. As a result, detection and reporting of new outbreaks may be delayed.

2 Because Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (the mosquitoes that most commonly spreads Zika) are present in these countries, Zika has the potential to be present, along with other mosquito-borne infections. Detection and reporting of cases and outbreaks may be delayed.

3 No Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (the mosquitoes that most commonly spreads Zika) have been reported in these countries. However, other Aedes species mosquitoes have been known to spread Zika, and these may be present.

[Source 4 ]See your doctor if you think you or a family member may have the Zika virus, especially if you have recently traveled to an area where there’s an ongoing outbreak. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has blood tests to look for the Zika virus and other viruses spread by mosquitoes.

If you’re pregnant and have recently traveled to an area where the Zika virus is common, ask your doctor whether you should be tested, even if you don’t have symptoms.

What is Dengue fever?

Dengue fever is mosquito-borne viral illness that occurs in tropical and subtropical areas of the world that spread by the same kinds of mosquitoes that spread Chikungunya virus and Zika virus. Dengue fever is common in warm, wet areas of the world. Outbreaks occur in the rainy season. Dengue is rare in the United States.

Millions of cases of dengue infection occur worldwide each year. Dengue fever is most common in Southeast Asia, the western Pacific islands, Latin America and Africa. But the disease has been spreading to new areas, including local outbreaks in Europe and southern parts of the United States.

Dengue fever symptoms include a high fever, headaches, joint and muscle pain, vomiting, and a rash. In some cases, dengue turns into dengue hemorrhagic fever, which causes bleeding from your nose, gums, or under your skin. It can also become dengue shock syndrome, which causes massive bleeding and a sudden drop in blood pressure (shock) and death. These forms of dengue are life-threatening.

There is no specific treatment for dengue. Most people with dengue recover within 2 weeks. Until then, drinking lots of fluids, resting and taking non-aspirin fever-reducing medicines might help. People with the more severe forms of dengue usually need to go to the hospital and get fluids.

Researchers are working on dengue fever vaccines. For now, in areas where dengue fever is common, the best ways to prevent infection are to avoid being bitten by mosquitoes and to take steps to reduce the mosquito population.

What is Yellow fever?

Yellow fever is a mosquito-borne viral disease that is spread to people primarily through the bite of infected Aedes or Haemagogus species mosquitoes 5. Yellow fever virus is a single-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the genus Flavivirus. It is related to West Nile, St. Louis encephalitis, and Japanese encephalitis viruses. Aedes or Haemagogus species mosquitoes acquire the Yellow fever virus by feeding on infected primates (human or non-human) and then can transmit the virus to other primates (human or non-human). People infected with yellow fever virus are infectious to mosquitoes (referred to as being “viremic”) shortly before the onset of fever and up to 5 days after onset.

Yellow fever virus has three transmission cycles: jungle (sylvatic), intermediate (savannah), and urban.

- The jungle (sylvatic) cycle involves transmission of the virus between non-human primates (e.g., monkeys) and mosquito species found in the forest canopy. The virus is transmitted by mosquitoes from monkeys to humans when humans are visiting or working in the jungle.

- In Africa, an intermediate (savannah) cycle exists that involves transmission of virus from mosquitoes to humans living or working in jungle border areas. In this cycle, the virus can be transmitted from monkey to human or from human to human via mosquitoes.

- The urban cycle involves transmission of the virus between humans and urban mosquitoes, primarily Aedes aegypti. The virus is usually brought to the urban setting by a viremic human who was infected in the jungle or savannah.

Yellow fever infection is most common in areas of Africa and South America, affecting travelers to and residents of those areas.

Yellow fever has 3 stages:

- Stage 1 (infection): Headache, muscle and joint aches, fever, flushing, loss of appetite, vomiting, and jaundice are common. Symptoms often go away briefly after about 3 to 4 days.

- Stage 2 (remission): Fever and other symptoms go away. Most people will recover at this stage, but others may get worse within 24 hours.

- Stage 3 (intoxication): Problems with many organs may occur, including the heart, liver, and kidney. Bleeding disorders, seizures, coma, and delirium may also occur.

Symptoms may include:

- Fever, headache, muscle aches

- Nausea and vomiting, possibly vomiting blood

- Red eyes, face, tongue

- Yellow skin and eyes (jaundice)

- Decreased urination

- Delirium

- Irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias)

- Bleeding (may progress to hemorrhage)

- Seizures

- Coma

In mild cases, yellow fever causes a fever, headache, nausea and vomiting. But yellow fever can become more serious, causing heart, liver and kidney problems along with bleeding. Up to 50% of people with the more-severe form of yellow fever die of the disease.

There’s no specific treatment for yellow fever. But getting a yellow fever vaccine before traveling to an area in which the virus is known to exist can protect you from the disease.

A single dose of the yellow fever vaccine provides protection for at least 10 years. Side effects are usually mild, lasting five to 10 days, and may include headaches, low-grade fevers, muscle pain, fatigue and soreness at the site of injection. More-significant reactions — such as developing a syndrome similar to actual yellow fever, inflammation of the brain or death — can occur, most often in infants and older adults. The vaccine is considered safest for those between the ages of 9 months and 60 years.

Talk to your doctor about whether the yellow fever vaccine is appropriate if your child is younger than 9 months, if you have a weakened immune system, are pregnant or if you’re older than 60 years.

What is Chikungunya fever?

Chikungunya also known as Chikungunya virus infection, is a mosquito-borne viral disease that spread by the same kinds of mosquitoes that spread dengue and Zika virus. Rarely, Chikungunya can spread from mother to newborn around the time of birth. It may also possibly spread through infected blood. Chikungunya was first described during an outbreak in southern Tanzania in 1952 and has now been identified in nearly 40 countries in Asia, Africa, Europe, the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the Caribbean, and Central and South America 6.

Chikungunya is an RNA virus that belongs to the alphavirus genus of the family Togaviridae. The name “chikungunya” derives from a word in the Kimakonde language, meaning “to become contorted”, and describes the stooped appearance of sufferers with joint pain (arthralgia).

Most people who are infected will have symptoms, which can be severe. They usually start 3-7 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito, but can appear anywhere from 2 to 12 days. The most common symptoms are fever and joint pain. Other symptoms may include headache, muscle pain, joint swelling, and rash.

Most people feel better within a week. In some cases, however, the joint pain may last for months. People at risk for more severe disease include newborns, older adults, and people with diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or heart disease.

A blood test can show whether you have chikungunya virus.

There are no vaccines or medicines to treat it. Like the flu virus, it has to run its course. You can take steps to help relieve symptoms:

- Drink plenty of fluids to stay hydrated.

- Get plenty of rest.

- Take ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil), naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn), or acetaminophen (Tylenol) to relieve pain and fever.

What is Ebola?

Ebola virus disease also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is a rare but severe viral illness and often fatal illness in humans, that is caused by infection with Zaire ebolavirus. Ebola hemorrhagic fever can affect humans and other primates. Researchers believe that the virus first spreads from an infected animal to a human. It can then spread from human to human through direct contact with a patient’s blood or secretions.

Ebola is not transmitted through the air. Unlike a cold or the flu, the Ebola virus is not spread by tiny droplets that remain in the air after an infected person coughs or sneezes.

Ebola is spread between humans when an uninfected person has direct contact with body fluids of a person who is sick with the disease or has died 7. People become contagious when they develop symptoms.

Body fluids that can transmit Ebola include:

- Blood

- Feces

- Vomit

- Urine

- Semen

- Saliva

- Breast milk

- Vaginal fluids

- Pregnancy-related fluids

- Tears

- Sweat

Symptoms of Ebola may appear anywhere from 2 to 21 days after exposure to the virus. Symptoms usually include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Joint and muscle aches

- Weakness

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Stomach pain

- Lack of appetite

Other symptoms including rash, red eyes, and internal and external bleeding, may also occur.

The early symptoms of Ebola are similar to other, more common, diseases. This makes it difficult to diagnose Ebola in someone who has been infected for only a few days. However, if a person has the early symptoms of Ebola and there is reason to suspect Ebola, the patient should be isolated. It is also important to notify public health professionals. Lab tests can confirm whether the patient has Ebola.

There is no cure for Ebola. But vaccines to protect against Ebola have been developed and have been used to help control the spread of Ebola outbreaks in Guinea and in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the Ebola vaccine (ERVEBO®), for the prevention of Ebola virus disease. ERVEBO vaccine is given as a single dose vaccine and has been found to be safe and protective against only the Zaire ebolavirus species of ebolavirus, which has caused the largest and most deadly Ebola outbreaks to date.

Ebola virus disease treatment involves supportive care such as fluids, oxygen, and treatment of complications. Some people who get Ebola are able to recover, but many do not.

Two monoclonal antibodies (Inmazeb and Ebanga) were approved for the treatment of Zaire ebolavirus (Ebolavirus) infection in adults and children by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2020 8. Monoclonal antibodies are proteins produced in a lab or other manufacturing facility that act like natural antibodies to stop a germ such as a virus from replicating after it has infected a person. These particular monoclonal antibodies bind to a portion of the Ebola virus’s surface called the glycoprotein, which prevents the virus from entering a person’s cells. Both of these treatments, along with two others, were evaluated in a randomized controlled trial during the 2018-2020 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Overall survival was much higher for patients receiving either of the two treatments that are now approved by the FDA. Neither Inmazeb nor Ebanga have been evaluated for efficacy against species other than Zaire ebolavirus.

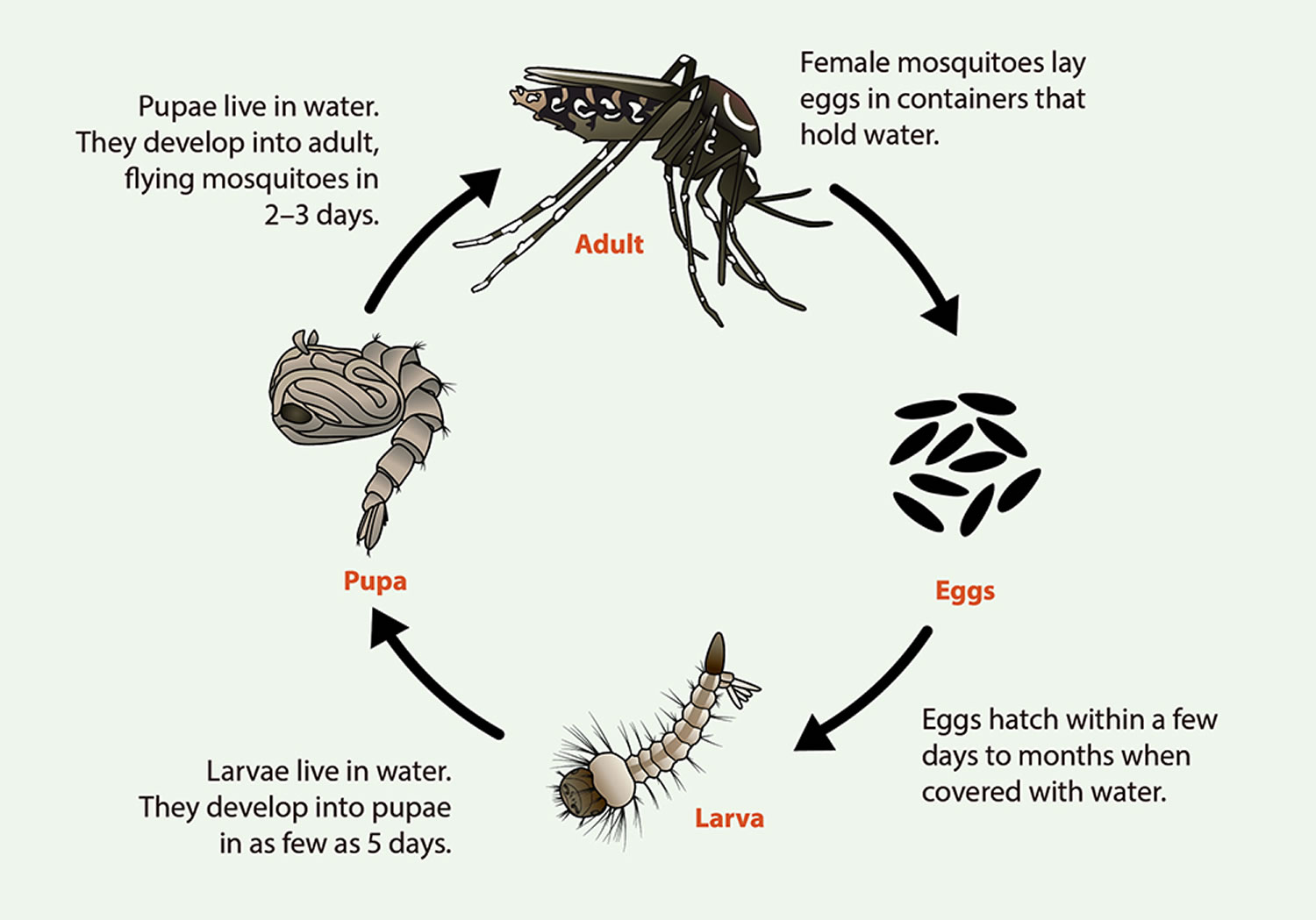

Life cycle of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes

It takes about 7-10 days for an egg to develop into an adult mosquito.

Eggs

- Adult, female mosquitoes lay eggs on the inner walls of containers with water, above the waterline.

- Eggs stick to container walls like glue. They can survive drying out for up to 8 months. Mosquito eggs can even survive a winter in the southern United States.

- Mosquitoes only need a small amount of water to lay eggs. Bowls, cups, fountains, tires, barrels, vases, and any other container storing water make a great “nursery.”

Larvae

- Larvae live in the water. They hatch from mosquito eggs. This happens when water (from rain or a sprinkler) covers the eggs.

- Larvae can be seen in the water. They are very active and are often called “wigglers.”

Pupae

- Pupae live in the water. An adult mosquito emerges from the pupa and flies away.

Adult mosquitoes

- Adult female mosquitoes bite people and animals. Mosquitoes need blood to produce eggs.

- After feeding, female mosquitoes look for water sources to lay eggs.

- Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus don’t fly long distances. In its lifetime, these mosquitoes will only fly within a few blocks.

- Aedes aegypti mosquitoes prefer to live near and bite people.

- Because Aedes albopictus mosquitoes bite people and animals, they can live in or near homes or in neighboring woods.

- Aedes aegypti mosquitoes live indoors and outdoors, while Aedes albopictus live outdoors.

Figure 4. Life cycle of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes

Figure 5. Aedes mosquito eggs (eggs look like black dirt)

Figure 6. Mosquito larvae (mosquito larvae live in water)

Figure 7. Mosquito pupae (Aedes aegypti mosquito pupae in standing water)

Zika fever symptoms

As many as 4 out of 5 people infected with the Zika virus have no signs or symptoms. When symptoms do occur, they usually begin two to 14 days after a person is bitten by an infected mosquito. Symptoms usually last about a week, and most people recover fully.

Signs and symptoms of the Zika virus most commonly include:

- Mild fever

- Rash

- Joint pain, particularly in the hands or feet

- Red eyes (conjunctivitis)

Other signs and symptoms may include:

- Muscle pain

- Headache

- Eye pain

- Fatigue or a general feeling of discomfort

- Abdominal pain

Zika fever complications

Women who are infected with the Zika virus during pregnancy have an increased risk of miscarriage, preterm birth and stillbirth. Zika virus infection during pregnancy also increases the risk of serious birth defects in infants (congenital Zika syndrome), including:

- A much smaller than normal brain and head size (mirocephaly), with a partly collapsed skull

- Brain damage and reduced brain tissue

- Eye damage

- Joint problems, including limited motion

- Reduced body movement due to too much muscle tone after birth

In adults, infection with the Zika virus may cause brain or nervous system complications, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, even in people who never show symptoms of infection.

Zika fever in pregnancy

If a woman gets Zika fever during pregnancy, the virus can pass to the developing baby 9, 10. Four out of 5 people who are infected with Zika do not have any symptoms – but they can still pass the virus to others through sexual contact or to a developing baby in pregnancy.

Zika virus infection during pregnancy presents with similar symptoms as those described for nonpregnant individuals, usually a mild disease 11, 12. The disease is mild and self-limited, usually lasting 4–6 days 13. The most common signs and symptoms include itchy rash, arthralgia, conjunctivitis, and low-grade fever 14. A review of Zika fever in pregnancy by Lin et al 15 summarized the published maternal symptoms in order of frequency as follows: “maculopapular rash (sometimes pruritic) affecting 44%–93% of cases, followed by conjunctivitis (36%–58%), myalgia/arthralgia (39%–64%), headaches (53%–62%) and lymphadenopathy (about 40%)”. Zika infection in pregnancy can also increase the chance of miscarriage or stillbirth.

Babies who are exposed to Zika virus during pregnancy have an increased chance of certain birth defects and developmental problems known as “congenital Zika syndrome” (CZS) 16. A congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) has been characterized with 5 distinctive features that focus on brain development abnormalities (including microcephaly and brain calcifications), retinal manifestations, and defects on extremities including congenital contractures and hypertonia 13.

Babies who have congenital Zika syndrome can have 16:

- A very small head and brain (severe microcephaly in which the skull has partially collapsed),

- Severe brain defects (decreased brain tissue with a specific pattern of brain damage, including subcortical calcifications),

- Eye defects (damage to the back of the eye, including macular scarring and focal retinal pigmentary mottling),

- Hearing loss,

- Seizures, and/or problems with joint and limb movement

- congenital contractures, such as clubfoot or arthrogryposis

- hypertonia restricting body movement soon after birth

Congenital Zika virus infection has also been associated with other abnormalities, including but not limited to brain atrophy and asymmetry, abnormally formed or absent brain structures, hydrocephalus, and neuronal migration disorders 16. Other anomalies include excessive and redundant scalp skin. Reported neurologic findings include hyperreflexia, irritability, tremors, seizures, brainstem dysfunction, and dysphagia. Reported eye abnormalities include, but are not limited to, focal pigmentary mottling and chorioretinal atrophy in the macula, optic nerve hypoplasia or atrophy, other retinal lesions, iris colobomas, congenital glaucoma, microphthalmia, lens subluxation, cataracts, and intraocular calcifications.

Current evidence suggests that Zika infection prior to pregnancy would not pose a risk of birth defects to a future pregnancy. From what scientists know about similar infections, once a person has been infected with Zika virus, they are likely to be protected from a future Zika infection 17. Currently, we do not have a test to tell if someone is protected against Zika virus. If you’re thinking about having a baby in the near future and you or your partner live in or traveled to an area with a Zika outbreak (red areas on the Zika map see Figure 3) or an area with risk of Zika (purple areas on Zika map see Figure 3), talk with your doctor or other healthcare provider.

Zika virus has been found in breast milk, but there are no reports of infants getting Zika through breastfeeding. Based on current information, experts believe that the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh any potential risks of Zika infection through breastfeeding 18. Be sure to talk to your healthcare provider about all your breastfeeding questions.

How can I protect my pregnancy from Zika virus?

If you are not pregnant yet, it is recommended to wait before trying to get pregnant after a known or possible exposure to Zika virus 19. Women should wait at least 2 months and men should wait at least 3 months, even if they do not have symptoms. During these wait times, everyone should use barrier methods (like condoms) and effective birth control to prevent pregnancy and protect their sexual partners from the virus (see Table 2 below).

If you are pregnant, avoid traveling to areas where there are known outbreaks of Zika (red areas on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Zika map see Figure 3), and carefully consider the risks of Zika before traveling to areas where there may be a chance of infection (purple areas on the map). If you travel to an area with a chance of Zika, help prevent mosquito bites by using insect repellent and taking other precautions recommended by the CDC and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents).

If you are pregnant, avoid having sex with a partner who might have the virus, or use a barrier method like a condom every time for vaginal, anal, or oral sex, for the rest of the pregnancy.

Table 2. Considerations for people planning to conceive and planning to travel to an area with a Zika outbreak or other areas with risk of Zika

| Traveling Partner | How Long to Wait |

|---|---|

| If only a male partner travels to an area with a Zika outbreak or other areas with risk of Zika | The couple should use condoms or not have sex for at least 3 months:

|

| If only a female partner travels to an area with a Zika outbreak or other areas with risk of Zika | They should use condoms or not have sex for at least 2 months:

|

| If both partners travel to an area with a Zika outbreak or other areas with risk of Zika | They should use condoms or not have sex for at least 3 months:

|

Footnotes: The timeframes that males and females should consider waiting are different because Zika can be found in semen longer than in other body fluids.

Decisions about pregnancy planning are personal and complex, and circumstances will vary for people trying to conceive. People should discuss pregnancy planning with a trusted doctor or healthcare provider.

Planning considerations include:

- their reproductive life plans, including pregnancy intentions and timing of pregnancy

- their potential exposures to Zika during pregnancy and the health risks and potential consequences of infection

- individual circumstances and level of risk tolerance

Table 3. Zika Testing if you are Pregnant and had Possible Exposure to an Area with a Zika outbreak or an Area with risk of Zika

| If you… | When to be tested |

|---|---|

| Traveled to an area with risk of Zika or had sex with a partner who lived in or traveled to one of these areas | You should be tested if you have symptoms of Zika or if an ultrasound shows that your fetus has abnormalities that might be related to Zika infection. Routine testing is not recommended if you are exposed to these areas and do not have symptoms. However, your doctor may offer testing based on your individual situation. |

| Live in or frequently travel (daily or weekly) to an area with risk of Zika | If you have symptoms of Zika at any time during your pregnancy, you should be tested for Zika. If you do not have symptoms, you should be offered testing at your first prenatal care visit, followed by two additional rounds of testing at regular prenatal care visits during your pregnancy. |

Does having Zika virus increase the chance for miscarriage?

Miscarriage can occur in any pregnancy. Zika infection in pregnancy can increase the chance of miscarriage.

Does having Zika virus in pregnancy increase the chance of birth defects?

Every pregnancy starts out with a 3-5% chance of having a birth defect. This is called the background risk. When a person who is pregnant gets Zika, the virus can pass to the developing baby. If this happens, the baby has an increased chance of certain birth defects and developmental problems known as congenital Zika syndrome (CZS). Congenital Zika syndrome can include microcephaly (very small head and brain), severe brain defects, eye defects, hearing loss, seizures, and/or problems with the development and movement of the joints and limbs.

Studies suggest that about 5-10% of babies born to people with confirmed Zika infection during pregnancy will have birth defects related to the infection. The chance is highest with a Zika infection in the first trimester, but birth defects related to Zika can also happen after infection in the second or third trimester.

In addition to birth defects and other problems related to congenital Zika syndrome (CZS), a Zika infection in pregnancy can increase the chance of stillbirth, preterm delivery (birth before week 37), and effects on the baby’s growth, including being smaller than expected for the timing in pregnancy (small for gestational age) and having low birth weight (weighing less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces [2500 grams] at birth).

Does having Zika virus in pregnancy affect future behavior or learning for the child?

Sometimes a baby can be born with no apparent effects from Zika infection, but can later have slowed head and brain growth (called postnatal microcephaly). Research has also shown that even when a baby does not have noticeable Zika-associated birth defects or postnatal microcephaly, there is still a chance they can later have problems related to brain damage, including delays meeting their developmental milestones. As they grow older, children affected by Zika will need ongoing specialized care from many types of healthcare providers and caregivers.

Can I just be tested for Zika virus instead of waiting to get pregnant or using condoms?

Zika testing is not a good way to know if it is safe to get pregnant or if you could pass the virus to your partner through sex. At this time there is no way to test the semen for Zika virus. People with possible or known exposure to the virus should wait the recommended times before trying to get pregnant (2 months for women and 3 months for men), and men with pregnant sex partners should use condoms for the rest of the pregnancy, even if they receive a negative Zika blood test result.

If a male has Zika virus, could it affect fertility (ability to get partner pregnant) or increase the chance of birth defects?

A study showed that having a Zika infection lowered sperm count (number of sperms produced), but sperm count returned to normal within several months after infection. More research is needed to know about any long-term effects of a Zika infection on a man’s fertility.

If a male has Zika he can pass the virus to his partner through unprotected sex. This can increase the chance of birth defects in his partner’s pregnancy. Males who might have been exposed to Zika virus should use condoms and wait at least 3 months before trying to conceive a pregnancy, even if they do not have symptoms.

Zika fever causes

The Zika virus is most often spread to a person through the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito (Aedes aegypti mosquito and Aedes albopictus mosquito). The two Aedes species mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti mosquito and Aedes albopictus mosquito, that are known to carry the Zika virus can be found throughout the world. These are the same mosquitoes that spread dengue and chikungunya viruses.

How the Zika virus can be transmitted:

- Through Aedes species mosquito (Aedes aegypti mosquito and Aedes albopictus mosquito) bites

- From a pregnant woman to her fetus

- Through sex without a condom with someone infected by Zika, even if that person does not show symptoms of Zika. Other ways people can get Zika include sexual contact with an infected partner (vaginal, anal, or oral sex, or sharing of sex toys)

- Through blood to blood contact with infected blood (from transfusions, needle sticks, or sharing needles with an infected person). Blood donations in the United States are screened for Zika virus. (Zika virus through blood transfusion very likely but not confirmed)

When a mosquito bites a person who is already infected with the Zika virus, the virus infects the mosquito. Then, when the infected mosquito bites another person, the virus enters that person’s bloodstream and causes an infection.

During pregnancy, the Zika virus can also spread from a mother to the fetus.

The virus can also spread from one person to another through sexual contact. In some cases, people contract the virus through blood transfusion or organ donation. However, to date, there have not been any confirmed blood transfusion transmission cases in the United States 20. There have been multiple reports of possible blood transfusion transmission cases in Brazil. During the French Polynesian outbreak, 2.8% of blood donors tested positive for Zika and in previous outbreaks, the virus has been found in blood donors.

There are reports of laboratory acquired Zika virus infections, although the route of transmission was not clearly established in all cases.

Risk factors for getting Zika fever

Factors that put you at greater risk of catching the Zika virus include:

- Living or traveling in countries where there have been outbreaks. Being in tropical and subtropical areas increases your risk of exposure to the Zika virus. Especially high-risk areas include several of the Pacific Islands, a number of countries in Central, South and North America, and islands near West Africa. Because the mosquitoes that carry the Zika virus are found worldwide, it’s likely that outbreaks will continue to spread to new regions. Most cases of Zika virus infection in the U.S. have been reported in travelers returning to the U.S. from other areas. But the mosquitoes that carry the Zika virus do live in some parts of the United States and its territories. Local transmission has been reported in Florida, Texas, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico.

- Having unprotected sex. The Zika virus can spread from one person to another through sex. Having unprotected sex can increase the risk of Zika virus infection for up to three months after travel. For this reason, pregnant women whose sex partners recently lived in or traveled to an area where Zika virus is common should use a condom during sexual activity or abstain from sexual activity until the baby is born. All other couples can also reduce the risk of sexual transmission by using a condom or abstaining from sexual activity for up to three months after travel.

Zika fever prevention

There is no vaccine to protect against the Zika virus. But you can take steps to reduce your risk of exposure to the Zika virus.

During travel or while living in an area with risk of Zika:

- Protective measures:

- Prevent mosquito bites by using Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents) with one of the active ingredients below and wear protective clothing. When you go into mosquito-infested areas, wear a long-sleeved shirt, long pants, socks and shoes. When used as directed, EPA-registered insect repellents are proven safe and effective, even for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

- DEET

- Picaridin (known as KBR 3023 and icaridin outside the US)

- IR3535

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE)

- Para-menthane-diol (PMD)

- 2-undecanone

- Prevent getting Zika infection through sex by using condoms from start to finish every time you have sex (oral, vaginal, or anal) or by not having sex during your pregnancy.

- Prevent mosquito bites by using Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents) with one of the active ingredients below and wear protective clothing. When you go into mosquito-infested areas, wear a long-sleeved shirt, long pants, socks and shoes. When used as directed, EPA-registered insect repellents are proven safe and effective, even for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

- Accommodations: Stay in places with air conditioning, with window and door screens, or sleep under a mosquito bed net.

- Type and length of exposure: For extended stays, there are steps you can take to control mosquitoes inside and outside, like removing standing water. It’s important for all travelers, including those visiting friends and relatives and those with extended stays, to protect themselves against Zika infection and other mosquito-borne illnesses during the entire visit.

After travel

- After any travel outside the United States during pregnancy, it is important to tell your doctor or health care provider about your travel because of the potential risk of various infectious diseases.

- If you or your partner travel to an area with a Zika outbreak or other areas with risk of Zika:

- Be alert for symptoms of Zika, including headache, rash, joint pain, red eyes.

- Take steps to prevent getting Zika through sex by using condoms from start to finish every time you have sex (oral, vaginal, or anal) or by not having sex during your entire pregnancy.

If you or your partner is pregnant or trying to get pregnant, these tips may help lower your risk of Zika virus infection:

- Plan travel carefully. The CDC recommends that all pregnant women avoid traveling to areas where there is an outbreak of the Zika virus. If you’re trying to become pregnant, talk to your doctor about whether you or your partner’s upcoming travel plans increase the risk of Zika virus infection. Your doctor may suggest you and your partner wait to try to conceive for two to three months after travel.

- Practice safe sex. If you have a partner who lives in or has traveled to an area where there is an outbreak of the Zika virus, the CDC recommends abstaining from sex during pregnancy or using a condom during all sexual activity.

Reduce mosquito habitat

The mosquitoes that carry the Zika virus usually live in and around houses and breed in standing water that has collected in containers such as animal dishes, flower pots and used automobile tires. At least once a week, empty any sources of standing water to help lower mosquito populations.

Zika virus and blood donation

In some cases, the Zika virus has spread from one person to another through blood products (blood transfusion). To date, there have been no confirmed transfusion-transmission cases of Zika virus in the United States 21. However, cases of Zika virus transmission through platelet transfusions have been documented in Brazil.

To reduce the risk of spread through blood transfusion, blood donation centers in the United States and its territories are required to screen all blood donations for the Zika virus. If you had Zika or if you live in the U.S. and recently traveled to an area where the Zika virus is widespread, your local blood donation center may recommend that you wait four weeks to donate blood.

Sexual transmission prevention

Infected people can pass Zika through sex even when they don’t have symptoms

- Many people infected with Zika virus won’t have symptoms or will only have mild symptoms, and they may not know they have been infected.

- Zika can also be passed from a person before their symptoms start, while they have symptoms, and after their symptoms end.

Zika can be passed through sex:

- Zika can be passed through sex from a person with Zika to his or her partners.

- Sex includes vaginal, anal, and oral sex and the sharing of sex toys.

- Zika can be passed through sex even in a committed relationship.

- The timeframes that men and women can pass Zika through sex are different because Zika virus can stay in semen longer than in other body fluids.

How to protect yourself during sex

- Condoms can reduce the chance of getting Zika from sex.

- Condoms include male and female condoms.

- To be effective, condoms should be used from start to finish, every time during vaginal, anal, and oral sex and the sharing of sex toys

- Dental dams may also be used for certain types of oral sex (mouth to vagina or mouth to anus).

- Not sharing sex toys can also reduce the risk of spreading Zika to sex partners.

- Not having sex eliminates the risk of getting Zika from sex.

Zika fever diagnosis

To diagnose Zika, your doctor will likely ask about your medical and travel history. Be sure to describe any international trips in detail, including the countries you and your sexual partner have visited, the dates of travel, and whether you may have had contact with mosquitoes.

Remember to ask for your Zika test results even if you are feeling better. Testing is recommended if you have symptoms of Zika and have traveled to a country with a current Zika outbreak (red areas). Note: There are no countries or U.S. territories currently reporting an outbreak of Zika 22.

If your doctor suspects that you may have a Zika virus infection, he or she may recommend a blood or urine test to confirm the diagnosis. The blood or urine samples can also be used to test for other, similar mosquito-borne diseases.

If you are pregnant and don’t have symptoms of Zika virus infection but you or your partner recently traveled to an area with active Zika virus transmission, ask your doctor if you need to be tested.

If you are pregnant and at risk of Zika virus infection, your doctor may also recommend one of the following procedures:

- An ultrasound to look for fetal brain problems. Pregnant women who have a fetus with prenatal ultrasound findings consistent with congenital Zika virus infection who live in or traveled to areas with a risk of Zika during her pregnancy:

- Zika virus nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) and Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody testing should be performed on maternal serum and NAAT on maternal urine.

- Due to the temporal nature of Zika virus RNA in serum and urine, a negative NAAT does not exclude recent Zika infection. For this reason, Zika virus immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibody testing is recommended in certain situations. IgM levels are variable, but generally become positive starting in the first week after onset of symptoms and continuing for up to 12 weeks post symptom onset or exposure, but may persist for months to years. Zika virus antibody testing is also complicated by cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses, which may make conclusive determination of which flavivirus is responsible for the person’s recent infection difficult. With IgM antibody testing, false-positive results are more common than with NAAT and can occur due to non-specific reactivity or cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses.

- If the Zika virus NAATs are negative and the IgM is positive, confirmatory plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNTs) should be performed against Zika and dengue.

- Plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNT) are quantitative assays that measure virus-specific neutralizing antibody titers. Plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNTs) can resolve false-positive IgM antibody results caused by non-specific reactivity and at times help identify the infecting virus. While most state health departments and many commercial laboratories perform dengue and Zika virus NAAT and IgM antibody testing, confirmatory neutralizing antibody testing using PRNT is currently only available through a limited number of state health departments and CDC. If Zika virus IgM antibody testing is positive and definitive diagnosis is needed for clinical or epidemiologic purposes, confirmatory PRNT should be performed against Zika and other flaviviruses endemic to the region where exposure occurred. PRNT might not discriminate between flaviviruses antibodies, especially following secondary flavivirus infections. Consequently, in areas with high prevalence of dengue and Zika virus neutralizing antibodies, PRNT may not confirm a significant proportion of IgM positive results. Therefore, such jurisdictions should make informed decisions about the utility of PRNT confirmation of IgM results depending on the prevalence of dengue and Zika virus neutralizing antibodies and observed performance of PRNT to confirm IgM test results.

- If amniocentesis is being performed as part of clinical care, Zika virus NAAT testing of amniocentesis specimens should also be performed and results interpreted within the context of the limitations of amniotic fluid testing. It is unknown how sensitive or specific RNA NAAT testing of amniotic fluid is for congenital Zika virus infection or what proportion of infants born after infection will have abnormalities.

- Testing of placental and fetal tissues may also be considered.

- Zika virus nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) and Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody testing should be performed on maternal serum and NAAT on maternal urine.

- Amniocentesis, which involves inserting a hollow needle into the uterus to remove a sample of amniotic fluid (amniocentesis) to be tested for the Zika virus

Zika Testing Guidance 2019

- Asymptomatic pregnant women 23:

- For asymptomatic pregnant persons living in or with recent travel to the U.S. and its territories, routine Zika virus testing is NOT currently recommended.

- For asymptomatic pregnant women with recent travel to an area with risk of Zika (purple areas) outside the U.S. and its territories, Zika virus testing is NOT routinely recommended, but nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) testing may still be considered up to 12 weeks after travel.

- Zika virus serologic testing is NOT recommended for asymptomatic pregnant women.

- Zika immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies can persist for months to years following infection. Therefore, detecting Zika IgM antibodies might not indicate a recent infection.

- There is notable cross-reactivity between dengue IgM and Zika IgM antibodies in serologic tests. Antibodies generated by a recent dengue virus infection can cause the Zika IgM to be falsely positive.

- Symptomatic pregnant patients 23:

- For symptomatic pregnant women who had recent travel to areas with active dengue transmission and a risk of Zika, specimens should be collected as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms up to 12 weeks after symptom onset.

- The following diagnostic testing should be performed at the same time:

- Dengue and Zika virus NAAT testing on a serum specimen, and Zika virus NAAT on a urine specimen, and

- IgM testing for dengue only.

- Zika virus IgM testing is NOT recommended for symptomatic pregnant women.

- Zika IgM antibodies can persist for months to years following infection. Therefore, detecting Zika IgM antibodies might not indicate a recent infection.

- There is notable cross-reactivity between dengue IgM and Zika IgM antibodies in serologic tests. Antibodies generated by a recent dengue virus infection can cause the Zika IgM to be falsely positive.

- If the Zika NAAT is positive on a single specimen, the Zika NAAT should be repeated on newly extracted RNA from the same specimen to rule out false-positive NAAT results. If the dengue NAAT is positive, this provides adequate evidence of a dengue infection and no further testing is indicated.

- If the IgM antibody test for dengue is positive, this is adequate evidence of a dengue infection and no further testing is indicated.

- The following diagnostic testing should be performed at the same time:

- For symptomatic pregnant women who have had sex with someone who lives in or recently traveled to areas with a risk of Zika, specimens should be collected as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms up to 12 weeks after symptom onset.

- Only Zika NAAT should be performed.

- If the Zika NAAT is positive on a single specimen, the Zika NAAT should be repeated on newly extracted RNA from the same specimen to rule out false-positive NAAT results.

- For symptomatic pregnant women who had recent travel to areas with active dengue transmission and a risk of Zika, specimens should be collected as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms up to 12 weeks after symptom onset.

Zika fever treatment

There is no specific treatment for infection with the Zika virus 24. To help relieve symptoms, get plenty of rest and drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration. The over-the-counter (OTC) medication acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) may help relieve joint pain and fever.

The symptoms of Zika virus infection are similar to other mosquito-borne illnesses, such as dengue fever. If you’re feeling ill after recent travel to an area where mosquito-borne illness is common, see your doctor. Don’t take ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve) or aspirin until your doctor has ruled out dengue fever. These medications can increase the risk of serious complications from dengue fever.

Individuals with Zika infection should be protected from mosquito exposure to reduce the risk of local transmission 25, 26.

If you are caring for a person with Zika

Take steps to protect yourself from exposure to the person’s blood and body fluids (urine, stool, vomit). If you are pregnant, you can care for someone with Zika if you follow these steps.

- Do not touch blood or body fluids or surfaces with these fluids on them with exposed skin.

- Wash hands with soap and water immediately after providing care.

- Immediately remove and wash clothes if they get blood or body fluids on them. Use laundry detergent and water temperature specified on the garment label. Using bleach is not necessary.

- Clean the sick person’s environment daily using household cleaners according to label instructions.

- Immediately clean surfaces that have blood or other body fluids on them using household cleaners and disinfectants according to label instructions.

If you visit a family member or friend with Zika in a hospital, you should avoid contact with the person’s blood and body fluids and surfaces with these fluids on them. Helping the person sit up or walk should not expose you. Make sure to wash your hands before and after touching the person.

Zika fever prognosis

Most cases of Zika virus infection is generally mild, and severe disease requiring hospitalization and deaths are uncommon 27. Rarely, Zika may cause Guillain-Barré syndrome, an uncommon sickness of the nervous system in which a person’s own immune system damages the nerve cells, causing muscle weakness, and sometimes, paralysis. Very rarely, Zika may cause severe disease affecting the brain, causing swelling of the brain or spinal cord or a blood disorder which can result in bleeding, bruising or slow blood clotting.

Zika infection during pregnancy can cause serious birth defects and developmental problems known as “congenital Zika syndrome” (CZS) 16. A congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) has been characterized with 5 distinctive features that focus on brain development abnormalities (including microcephaly and brain calcifications), retinal manifestations, and defects on extremities including congenital contractures and hypertonia 13.

References- Eftekhari-Hassanlouie S, Le Guern A, Oehler E. La fièvre zika [Zika fever]. Rev Med Interne. 2017 Aug;38(8):526-530. French. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2017.01.003

- Zika virus. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/zika-virus/symptoms-causes/syc-20353639

- Areas at Risk for Zika. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html

- Zika Travel Information. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/zika-information

- Transmission of Yellow Fever Virus. https://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/transmission/index.html

- Chikungunya. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/chikungunya

- Ebola virus disease. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ebola-virus-disease

- Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease) Treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/treatment/index.html

- Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Rice ME, Galang RR, et al. Pregnancy Outcomes After Maternal Zika Virus Infection During Pregnancy — U.S. Territories, January 1, 2016–April 25, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:615-621. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6623e1.htm

- Reynolds MR, Jones AM, Petersen EE, et al. Vital Signs: Update on Zika Virus–Associated Birth Defects and Evaluation of All U.S. Infants with Congenital Zika Virus Exposure — U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:366-373. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6613e1.htm

- Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, Pretrick M, Marfel M, Holzbauer S, Dubray C, Guillaumot L, Griggs A, Bel M, Lambert AJ, Laven J, Kosoy O, Panella A, Biggerstaff BJ, Fischer M, Hayes EB. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 11;360(24):2536-43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715

- Zika virus infection: global update on epidemiology and potentially associated clinical manifestations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2016 Feb 19;91(7):73-81. English, French.

- Zorrilla CD, García García I, García Fragoso L, De La Vega A. Zika Virus Infection in Pregnancy: Maternal, Fetal, and Neonatal Considerations. J Infect Dis. 2017 Dec 16;216(suppl_10):S891-S896. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix448

- Brasil P, Pereira JP Jr, Moreira ME, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, Rabello RS, Valderramos SG, Halai UA, Salles TS, Zin AA, Horovitz D, Daltro P, Boechat M, Raja Gabaglia C, Carvalho de Sequeira P, Pilotto JH, Medialdea-Carrera R, Cotrim da Cunha D, Abreu de Carvalho LM, Pone M, Machado Siqueira A, Calvet GA, Rodrigues Baião AE, Neves ES, Nassar de Carvalho PR, Hasue RH, Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Janzen C, Cherry JD, Bispo de Filippis AM, Nielsen-Saines K. Zika Virus Infection in Pregnant Women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375(24):2321-2334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412

- Lin HZ, Tambyah PA, Yong EL, Biswas A, Chan SY. A review of Zika virus infections in pregnancy and implications for antenatal care in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2017 Apr;58(4):171-178. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2017026

- Congenital Zika Syndrome & Other Birth Defects. https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/zika/testing-follow-up/zika-syndrome-birth-defects.html

- Zika During Pregnancy. https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/zika/protect-yourself.html

- Zika. How Zika Virus Infection Impacts Pregnancy & Breastfeeding. https://mothertobaby.org/pregnancy-breastfeeding-exposures/zika

- People Trying to Conceive. https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/zika/women-and-their-partners.html

- Zika Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/prevention/transmission-methods.html

- Zika and Blood Transfusion. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/transmission/blood-transfusion.html

- Testing for Zika. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/symptoms/diagnosis.html

- NEW Zika and Dengue Testing Guidance (Updated November 2019). https://www.cdc.gov/zika/hc-providers/testing-guidance.html

- Zika Virus Treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/symptoms/treatment.html

- Saiz JC, Oya NJ, Blázquez AB, Escribano-Romero E, Martín-Acebes MA. Host-Directed Antivirals: A Realistic Alternative to Fight Zika Virus. Viruses. 2018 Aug 24;10(9):453. doi: 10.3390/v10090453

- Leeper C, Lutzkanin A 3rd. Infections During Pregnancy. Prim Care. 2018 Sep;45(3):567-586. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.05.013

- Wolford RW, Schaefer TJ. Zika Virus. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430981