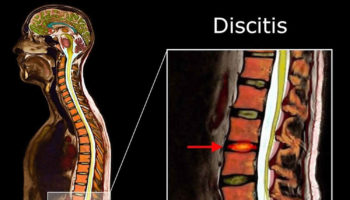

What is discitis Discitis is an inflammation or infection of the intervertebral disc or intervertebral disc space. Discitis can be caused by bacteria, virus, or fungus. Discitis

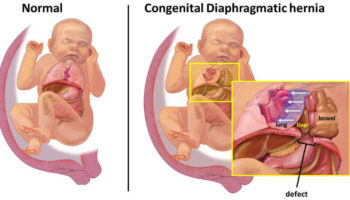

What is a diaphragmatic hernia A diaphragmatic hernia is also called congenital diaphragmatic hernia, is a birth defect in which there is an abnormal opening

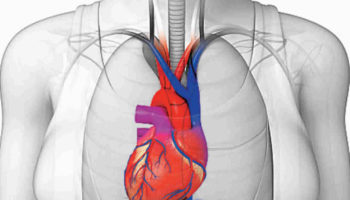

What is dextrocardia Dextrocardia is a rare condition in which the heart is located in the right side of the chest instead of the left.

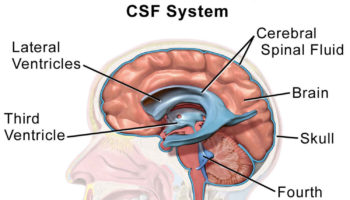

What is a CSF leak A CSF leak is an escape of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that surrounds your brain and spinal cord. CSF leaks have

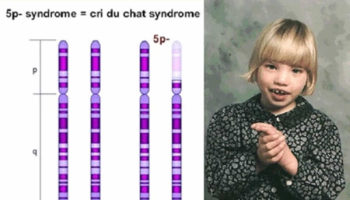

What is Cri du chat syndrome Cri du chat syndrome is a genetic disorder that result from missing a piece of chromosome number 5, also

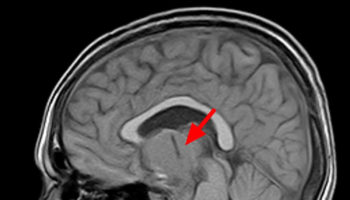

What is craniopharyngioma Craniopharyngiomas are rare benign (noncancerous) tumors that are typically found near the pituitary gland and hypothalamus, which are positioned beneath the center

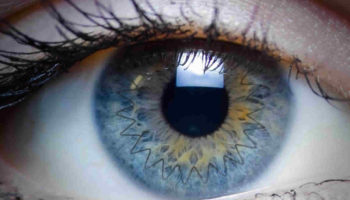

Corneal transplant surgery A corneal transplant also known as keratoplasty, is a surgical procedure that replaces a disc-shaped segment of an unhealthy cornea with a similarly

What is cryosurgery Cryosurgery is also called cryotherapy, is a medical procedure that uses intense cold produced by liquid nitrogen (or argon gas) to destroy

What is cerebral hypoxia Cerebral hypoxia or brain hypoxia refers to a condition in which there is a decrease of oxygen supply to the brain even

What is calcification Calcification is a process in which calcium builds up in body tissue, causing the tissue to harden. Calcification can be a normal