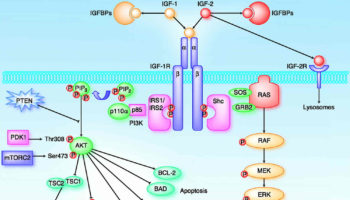

What is IGF IGFs (insulin-like growth factors) were previously known as somatomedins. IGF-2 (insulin-like growth factor-2) is believed to be the major fetal growth factor

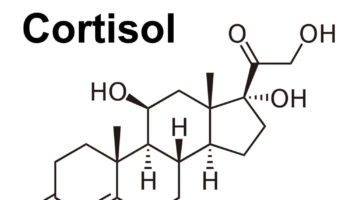

What are glucocorticoids Glucocorticoids are corticosteroid hormones, which are a class of essential steroid hormones, secreted from the adrenal glands, that are essential for life and

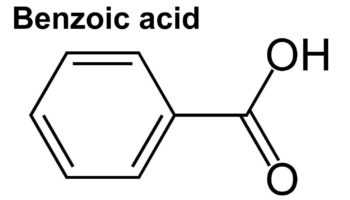

What is benzoic acid Benzoic acid is an aromatic carboxylic acid, a fungistatic compound that is widely used as a food preservative. Benzoic acid and

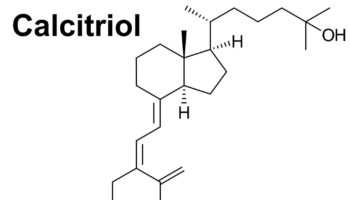

What is calcitriol Calcitriol is vitamin D3 also known as cholecalciferol or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D , a physiologically-active analog of vitamin D. Calcitriol (1,25(OH)2D) is the

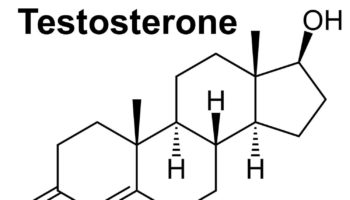

What is androgen Androgens also known as male sex hormones are an important class of C19 steroid hormones that control normal male development and reproductive

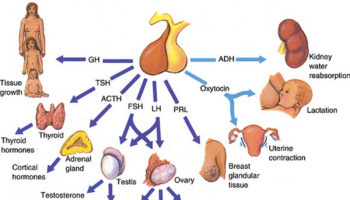

What is FSH FSH is short for follicle-stimulating hormone. FSH is a hormone associated with reproduction and the development of eggs in women and sperm

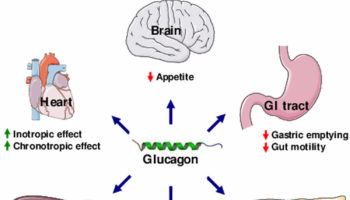

What is glucagon Glucagon is a hormone produced in the pancreas alpha cells in the islets of Langerhans and glucagon is secreted between meals when

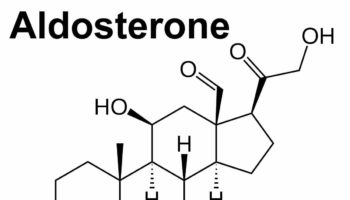

What is aldosterone Aldosterone also called mineralocorticoid, is a hormone that is crucial for sodium conservation in the kidney, salivary glands, sweat glands and colon.

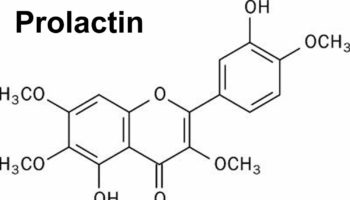

What is prolactin Prolactin is a hormone produced by the anterior pituitary gland, a grape-sized organ found at the base of the brain and controlled

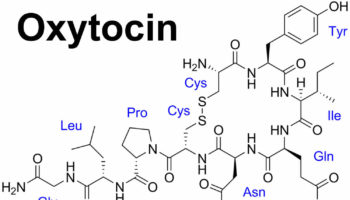

What is oxytocin Oxytocin is a nonapeptide hormone released in high levels during childbirth from the posterior pituitary gland at the base of your brain