Bifascicular block

Bifascicular block is a conduction delay or “block” below the atrioventricular (AV) node in two of the three fascicles (the right bundle branch and left anterior and left posterior fascicles of the left bundle branch). Right bundle branch block (RBBB) is typically combined with either left anterior fascicular block (LAFB) or left posterior fascicular block (LPFB) 1. Bifascicular block occurs in 1% to 2% of the adult population.

Ventricular depolarizaiton is facilitated by the heart’s electrical conduction system, sometimes referred to as the His/Purkinje system, which by convention is said to have three main fascicles or branches. There is a single fascicle in the right ventricle referred to as the right bundle branch. There are two fascicles in the left ventricle: the left anterior fascicle and the left posterior fascicle of the left bundle branch.

Bifascicular block refers to a combination of right bundle branch block (RBBB) with either either left anterior fascicular block (LAFB) or left posterior fascicular block (LPFB), with the former being more common.

Left bundle branch block (LBBB) alone is not considered bifascicular block [left anterior fascicular block (LAFB) plus left posterior fascicular block (LPFB)], although anatomically this may be the case. However, some authors consider left bundle branch block (LBBB) to be a technical bifascicular block, since the block occurs above the bifurcation of the left anterior and left posterior fascicles of the left bundle branch.

The problem with bifascicular block is that the heart’s electrical conduction system is down to one fascicle. As such, the patient may be at risk for complete heart block or third-degree heart block (which is what would happen if all three fascicles were blocked).

Although many patients have chronic bifascicular block for years and do not develop concerning symptoms, being mindful of the fact that patients with syncope and bifascicular block may be experiencing transient episodes of third degree AV block or even asystole (third degree AV block with no escape rhythm).

Bifascicular block is often associated with structural heart disease and may be associated with progression to high-grade block or complete heart block (third-degree heart block). The rate of progression to atrioventricular (AV) block is 1% to 4% per year and up to 17% per year for individuals with syncope. Bifascicular block in syncope patients is also associated with (but not causally related to) the presence of malignant ventricular arrhythmias. When first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block is associated with bifascicular block, there is the possibility (20% to 40% of cases in symptomatic patients) that there is trifascicular disease (i.e., the remaining fascicle is also involved), although in most cases the prolonged PR interval is due to block in the AV node (and not the remaining fascicle). Bifascicular block involving the right bundle branch and left anterior fascicle is more common than right bundle branch block (RBBB) and left posterior fascicular block (LPFB). This is due to a single coronary artery blood supply (left anterior descending) to the anterior fascicle, as well as its relationship to the left ventricular outflow tract, resulting in mechanotrauma to the fascicle. Bifascicular block involving the left posterior fascicle and the right bundle branch is less common due to a dual blood supply (right and left circumflex coronary arteries), and this combination may be associated with more extensive underlying cardiac pathology. The risk for progression to complete heart block may be greater. The mortality may be as high as 15% in 2 years, with a 9% risk of sudden death.

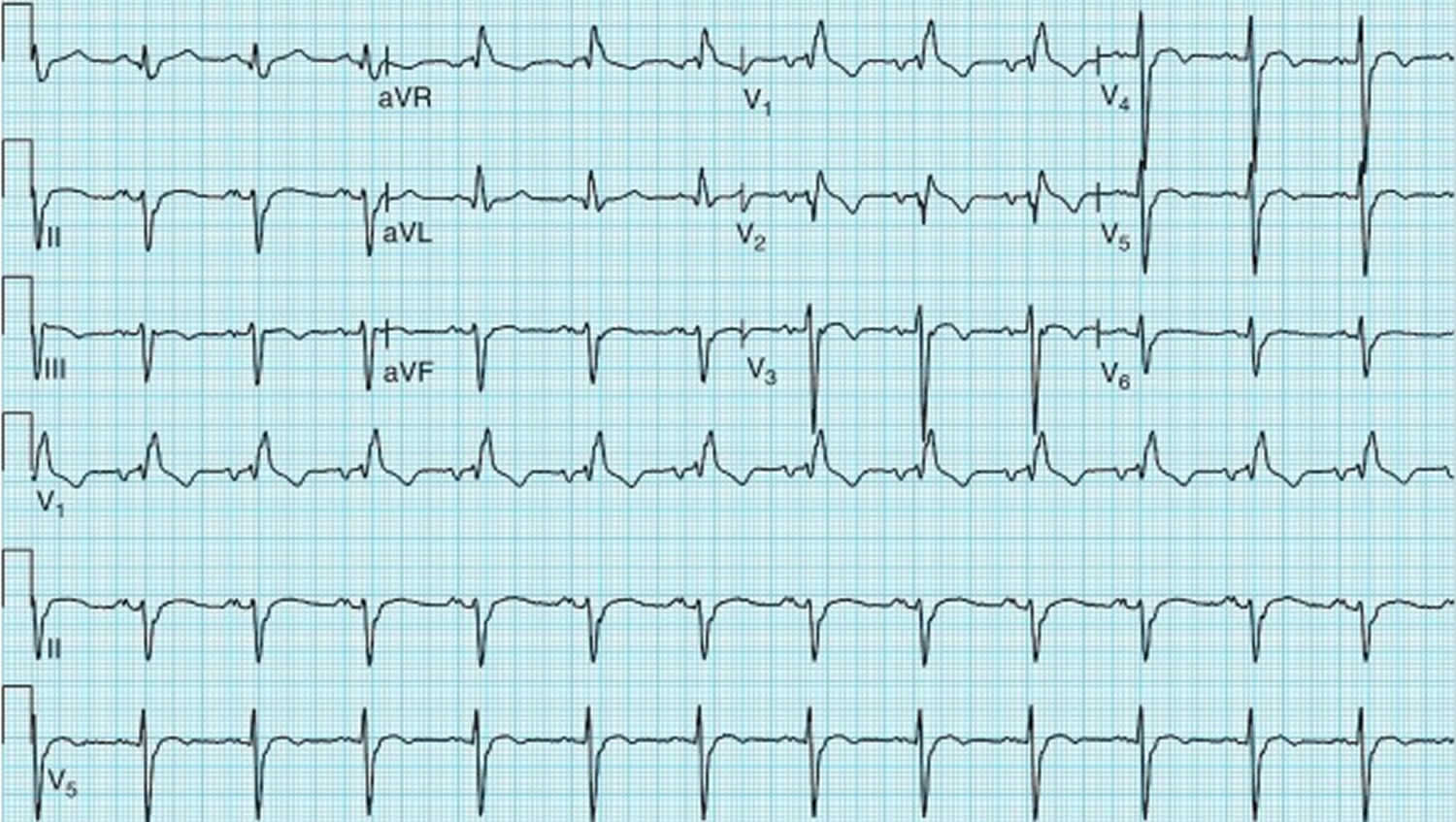

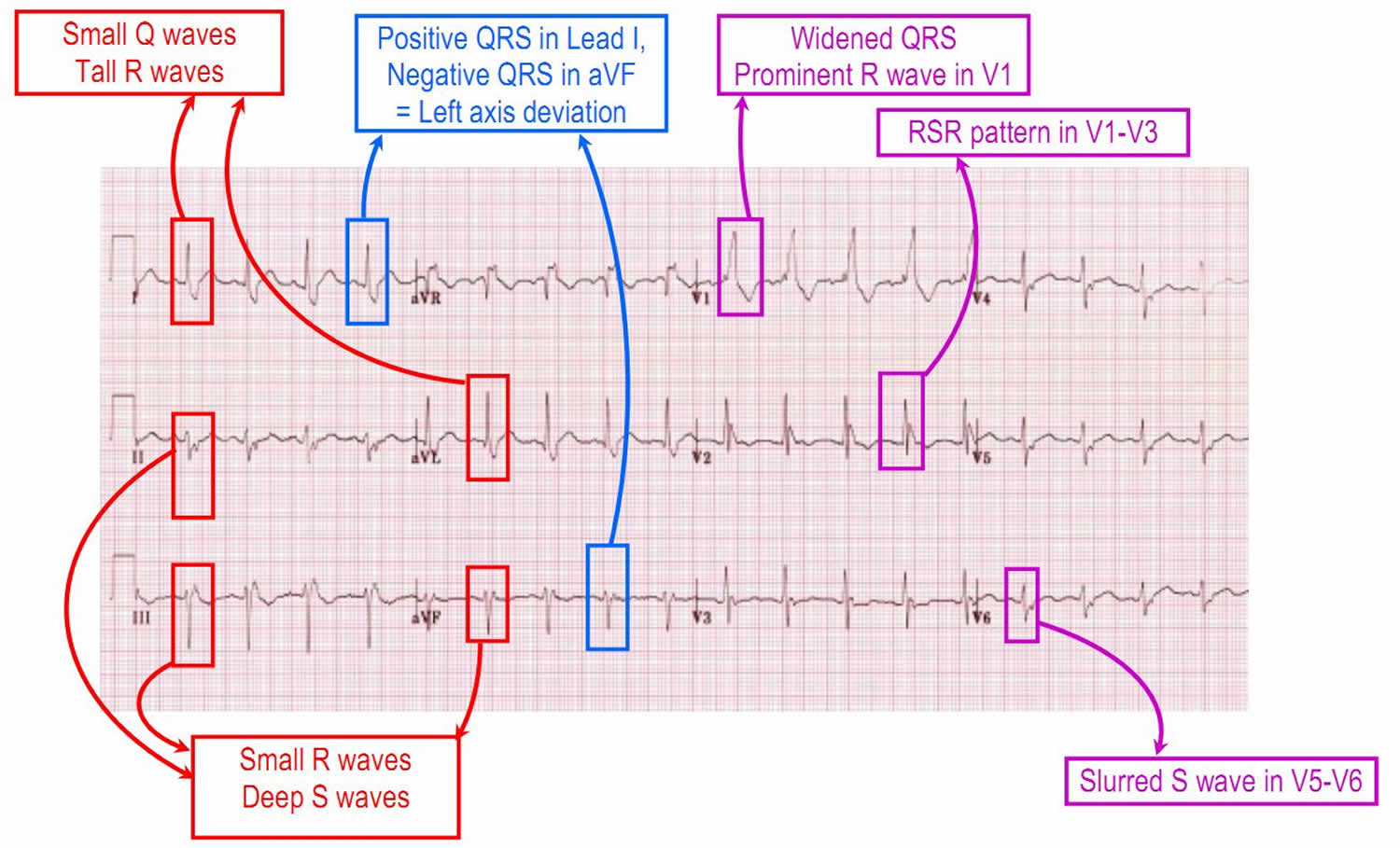

Figure 1. Bifascicular block showing right bundle branch block (RBBB) plus left anterior fascicular block (LAFB)

Footnote: 12-lead ECG shows a sinus rhythm with right bundle branch block (RBBB) and left anterior fascicular block (LAFB)

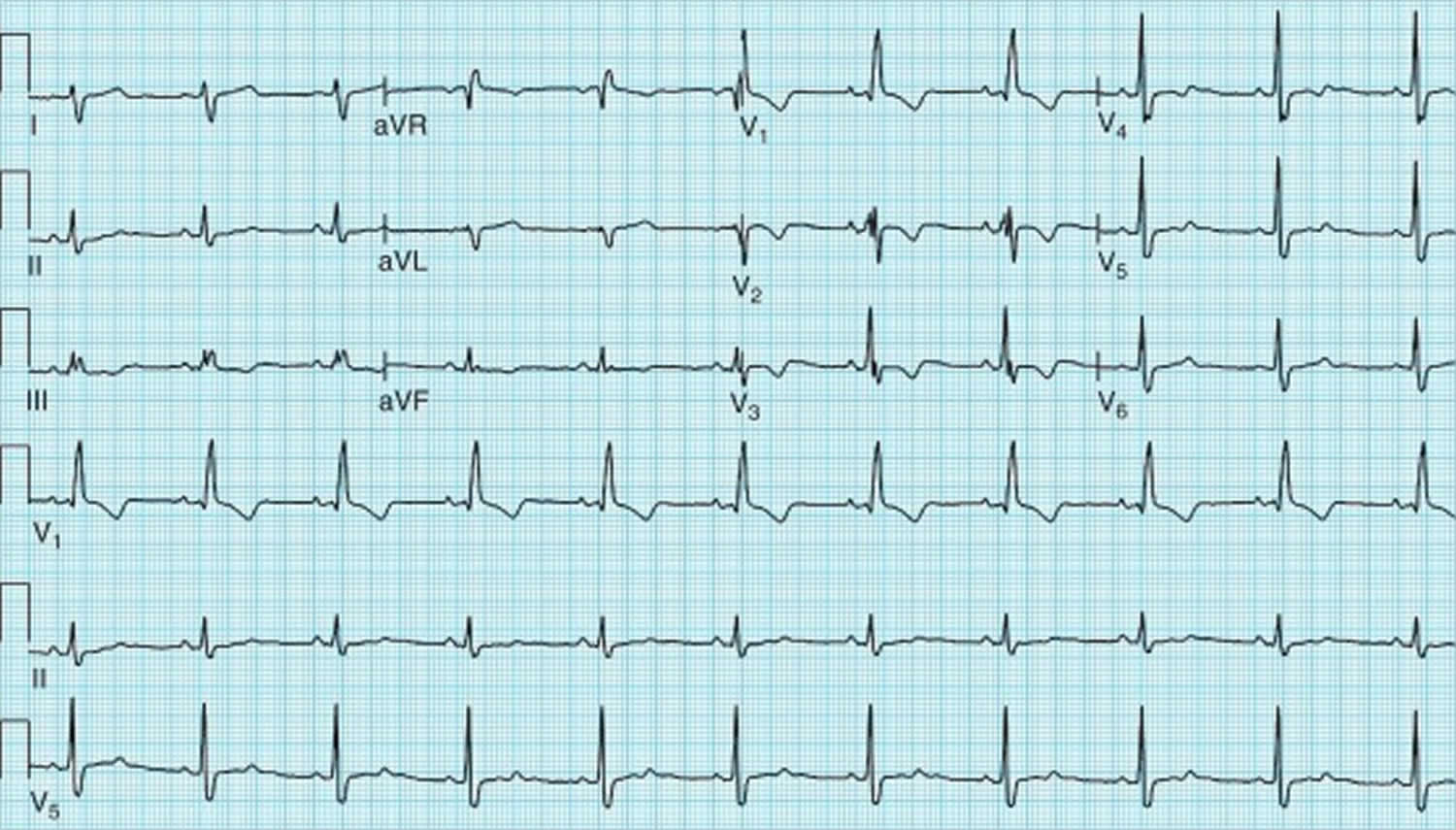

Figure 2. Bifascicular block showing right bundle branch block (RBBB) plus left posterior fascicular block (LPFB)

Footnote: 12-lead ECG shows sinus rhythm with right bundle branch block (RBBB) (wide rsR′ complex in lead V1 with a deep and wide S wave in lead V5 and V6) and left posterior fascicular block (LPFB) (with axis > + 100 degrees and no Q waves in I or aVL to suggest a lateral myocardial infarction).

If you’ve fainted, see your doctor to rule out serious causes.

If you have heart disease, or if your doctor has already diagnosed you as having bundle branch block, ask your doctor how often you should have follow-up visits. You might want to carry a medical alert card that identifies you as having bundle branch block in case a doctor who isn’t familiar with your medical history sees you in an emergency.

Is bifascicular block dangerous?

The main complication of bundle branch block, right or left, is to progress to a complete block of the electric conduction from the upper chambers of the heart to the lower, also called complete heart block or third-degree heart block. This can slow your heart rate, which can cause fainting and lead to serious complications and abnormal heart rhythms.

The heart’s electrical system

To understand the causes of heart block, it helps to understand how your heart’s internal electrical system works.

Your heart is made up of four chambers — two upper chambers (atria) and two lower chambers (ventricles).

Your heart’s electrical system is made up of three main parts:

- The sinoatrial (SA) node, located in the right atrium of your heart

- The atrioventricular (AV) node, located on the interatrial septum close to the tricuspid valve

- The His-Purkinje system, located along the walls of your heart’s ventricles

Each beat of your heart is set in motion by an electrical signal from within your heart muscle. The signal is generated as the vena cavae fill your heart’s right atrium with blood from other parts of your body. The signal spreads across the cells of your heart’s right and left atria. In a normal, healthy heart, each beat begins with a signal from the natural pacemaker called the sinoatrial (SA) node — or sinus node — an area of specialized cells in the right atrium. This is why the sinoatrial (SA) node sometimes is called your heart’s natural pacemaker. Your pulse, or heart rate, is the number of signals the SA node produces per minute.

The sinoatrial (SA) node produces electrical impulses that normally start each heartbeat. This natural pacemaker produces the electrical impulses that trigger the normal heartbeat. From the sinus node, electrical impulses travel across the atria to the ventricles, causing them to contract and pump blood to your lungs and body.

From the sinoatrial (SA) node, electrical impulses travel across the atria, causing the atrial muscles to contract and pump blood into the ventricles.

The electrical impulses then arrive at a cluster of cells called the atrioventricular (AV) node — usually the only pathway for signals to travel from the atria to the ventricles.

The atrioventricular (AV) node slows down the electrical signal before sending it to the ventricles. This slight delay allows the ventricles to fill with blood.

The signal is released and moves along a pathway called the bundle of His, which is located in the walls of your heart’s ventricles. From the bundle of His, the signal fibers divide into left and right bundle branches through the Purkinje fibers. These fibers connect directly to the cells in the walls of your heart’s left and right ventricles.

The signal spreads across the cells of your ventricle walls, and both ventricles contract. However, this doesn’t happen at exactly the same moment.

The left ventricle contracts an instant before the right ventricle. This pushes blood through the pulmonary valve (for the right ventricle) to your lungs, and through the aortic valve (for the left ventricle) to the rest of your body.

As the signal passes, the walls of the ventricles relax and await the next signal.

This process continues over and over as the atria refill with blood and more electrical signals come from the SA node.

When electrical impulses reach the muscles of the ventricles, they contract, causing them to pump blood either to the lungs or to the rest of your body.

When anything disrupts this complex system, it can cause the heart to beat too fast (tachycardia), too slow (bradycardia) or with an irregular rhythm.

Your heart’s electrical system controls all the events that occur when your heart pumps blood. The electrical system also is called the cardiac conduction system. If you’ve ever seen the heart test called an EKG (electrocardiogram), you’ve seen a graphical picture of the heart’s electrical activity.

Figure 3. The heart’s electrical system

Bifascicular block causes

Normally, electrical impulses within your heart’s muscle signal it to beat (contract). These impulses travel along a pathway, including the right and the left bundles. If one or both of these branch bundles become damaged — due to a heart attack, for example — this can block the electrical impulses and cause your heart to beat abnormally.

The cause for bundle branch blocks can differ depending on whether the left or right bundle branch is affected. It’s also possible that this condition can occur without a known cause.

Some people are born with heart block – known as congenital heart block.

But more commonly, heart block develops later in life. This is known as acquired heart block and can be caused by:

- other heart conditions, such as a heart attack

- taking certain medicines

- other diseases, such as Lyme disease

- having heart surgery

Left bundle branch block (LBBB)

- Heart attacks (myocardial infarction)

- Thickened, stiffened or weakened heart muscle (cardiomyopathy)

- A viral or bacterial infection of the heart muscle (myocarditis)

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

Right bundle branch block (RBBB)

- A heart abnormality that’s present at birth (congenital) — such as atrial septal defect, a hole in the wall separating the upper chambers of the heart

- A heart attack (myocardial infarction)

- A viral or bacterial infection of the heart muscle (myocarditis)

- High blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries (pulmonary hypertension)

- A blood clot in the lungs (pulmonary embolism)

Acquired heart block

Acquired heart block can affect people of any ages, but older people are more at risk.

There are several causes of acquired heart block, including:

- heart surgery – thought to be one of the most common causes of complete heart block

- being an athlete – some athletes get first-degree heart block because their hearts are often bigger than normal, which can slightly disrupt their heart’s electrical signals

- a history of coronary heart disease, heart attack or heart failure – this can leave the heart tissues damaged

- some diseases – such as myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, Lev’s disease, diphtheria or rheumatic fever

- exposure to some toxic substances

- low levels of potassium (hypokalaemia) or low magnesium (hypomagnesemia) in the blood

- high blood pressure (hypertension) that isn’t well controlled

- cancer that’s spread from another part of the body to the heart

- a penetrating trauma to the chest – such as a stab wound or gunshot wound

Certain medications can also cause first-degree heart block, including:

- medication for abnormal heart rhythms – such as disopyramide

- medications for high blood pressure – such as beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, or clonidine

- digoxin – a medication used to treat heart failure

- fingolimod – used for treating certain types of multiple sclerosis

- pentamidine – used to treat some types of pneumonia

- tricyclic antidepressants – such as amitriptyline

Risk factors for bifascicular block

Risk factors for bundle branch block include:

- Increasing age. Bundle branch block is more common in older adults than in younger people.

- Underlying health problems. Having high blood pressure or heart disease increases your risk of having bundle branch block.

Bifascicular block symptoms

In most people, bifascicular block doesn’t cause symptoms. Some people with bifascicular block don’t know they have a bundle branch block.

Signs and symptoms in people who have them might include:

- Fainting (syncope)

- Feeling as if you’re going to faint (presyncope).

Bifascicular block complications

The main complication of bundle branch block, right or left, is to progress to a complete block of the electric conduction from the upper chambers of the heart to the lower. This can slow your heart rate, which can cause fainting and lead to serious complications and abnormal heart rhythms.

People who have a heart attack and develop a left bundle branch block have a higher chance of complications, including sudden cardiac death, than do people who don’t develop the condition after a heart attack.

Because bundle branch block affects the electrical activity of your heart, it can sometimes complicate the accurate diagnosis of other heart conditions, especially heart attacks, and lead to delays in proper management of those problems.

Bifascicular block diagnosis

If you have a right bundle branch block (RBBB) and you’re otherwise healthy, you might not need a full evaluation. If you have a left bundle branch block (LBBB), you will need a full evaluation.

Tests that can be used to diagnose a bundle branch block or its causes include:

- Electrocardiogram. This records the electrical impulses in your heart through wires attached to the skin on your chest and other places on your body. Abnormalities might indicate a bundle branch block, as well as which side is being affected.

- Echocardiogram. This test uses sound waves to provide detailed images of the heart’s structure and shows the thickness of your heart muscle and whether your heart valves are moving normally. It can pinpoint a condition that caused the bundle branch block.

Bifascicular block treatment

Bifascicular block might not need treatment. Most people with bundle branch block are symptom-free and don’t need treatment. When it does, treatment involves managing the health condition, such as heart disease, that caused bundle branch block.

If you have a heart condition causing bundle branch block, treatment might involve medications to reduce high blood pressure or lessen the effects of heart failure.

Additionally, depending on your symptoms and whether you have other heart problems, your doctor might recommend:

- A pacemaker. If you have bundle branch block and a history of fainting, your doctor might recommend a pacemaker. This compact device is implanted under the skin of your upper chest (internal pacemaker) with two wires that connect to the right side of your heart. The pacemaker provides electrical impulses when needed to keep your heart beating regularly. In patients with syncope and bifascicular block without structural heart disease, treatment with empirical pacemaker, instead of a diagnosis strategy based on electrophysiology studies, result in a significant reduction of event during long term follow-up 2. 86% of patients in the electrophysiology studies group eventually required pacemakers 2.

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy. Also known as biventricular pacing, this procedure is similar to having a pacemaker implanted. However, with this procedure, there’s a third wire that’s connected to the left side of the heart so the device can keep both sides in proper rhythm. This therapy, which is meant to improve the coordination of both lower chambers of the heart so that they contract at the same time, is used in people with low pumping function and a bundle branch block.