Buried bumper syndrome

Buried bumper syndrome is a rare complication associated with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement, with an approximate incidence of 0.3%-2.4% 1. Buried bumper syndrome refers to the displacement of the internal gastrostomy bumper (the internal fixation device of the cannula) into the PEG stoma tract. The bumper disc can end up anywhere between the stomach mucosa and the surface of the skin. The internal bumper can be found covered by gastric mucosa endoscopically, completely buried in the gastric wall, and in severe cases traversing the stoma tract and found near the skin surface 1. Presentation depends on the time lag between insertion and diagnosis, as well as the technique utilized during placement.

The stoma channel evolves into the abscess cavity with infiltrate around the migrating disc, while it leaves a fistula towards the stomach lumen. This complication is typical for rigid or semi-rigid internal fixation devices, and cases complicating balloon fixation are rare 2. The mildest form of the buried bumper syndrome can be hyperplastic tissue growing over the edge of the disc or an ulcer below the disc. The other extreme is complete spontaneous dislocation of the PEG tube with the disc. Some authors limit the buried bumper syndrome to cases in which the disc is completely covered during endoscopy 3, but less advanced cases are also relevant because they can evolve into full buried bumper syndrome without proper precautions.

Excessive compression of tissue between the external and internal fixation device of the gastrostomy tube is considered the main etiological factor leading to buried bumper syndrome 4; other factors such as weight gain, chronic cough, and improper post-insertion PEG tube care can contribute to the presentation 5. Incidence of buried bumper syndrome is estimated at around 1% (0.3%-2.4%).

Proper positioning of the external bumper at the time of PEG tubes with J-extension (PEG-J) insertion is of the utmost importance in preventing buried bumper syndrome, with emphasis on leaving approximately 1 cm of space between the external bumper and the skin on insertion 6. Some authors believe that there is an underestimation of the true incidence of buried bumper syndrome due to the preserved functionality of the J port even when the internal bumper is completely buried in the gastric wall. Especially that patients using PEG-J for levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel administration only need the J extension and do not typically require the use of the G-tube 1. As such, some authors recommend frequent examination of the PEG tubes with J-extension (PEG-J) system post placement assuring the tube is minimally mobile and not tethered to the underlying deep tissue and they propose the continued use of the G-tube for twice daily water flushes to assure patency of the system and to avoid a late diagnosis of buried bumper syndrome 1.

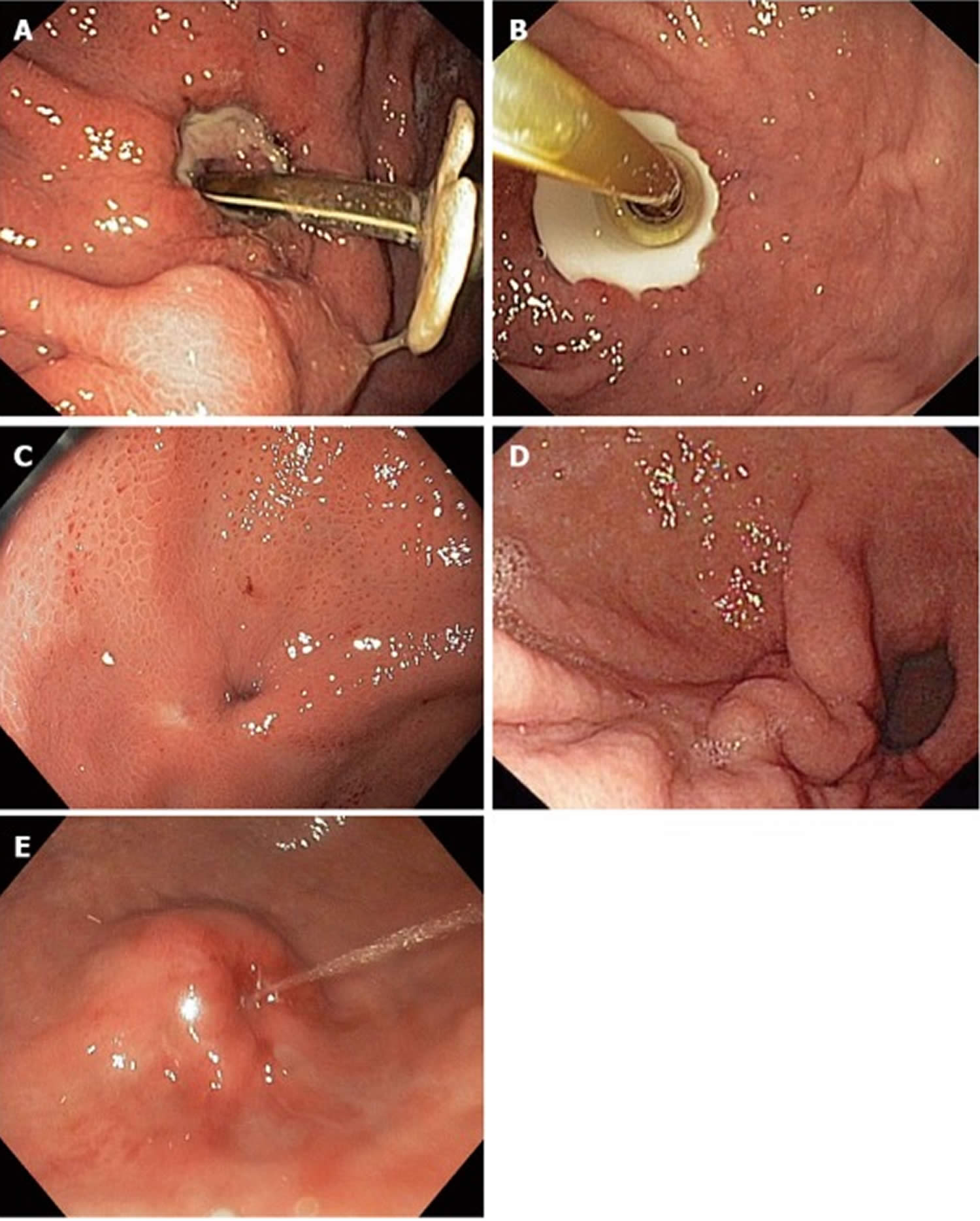

Figure 1. Buried bumper syndrome gastroscopy

Footnote: (A ) Pressure ulcer under the internal bolster repositioned to the gastric lumen; (B) Hyperplastic tissue growing over the edge of the disk; (C) Flat stomach wall with fistula orifice covering totally the internal bolster; (D) Completely buried disc retracting the gastric mucosa; (E) Internal bolster totally embedded in the stomach wall resembling a submucosal tumor. Flushing solution running from the internal orifice of the residual fistula.

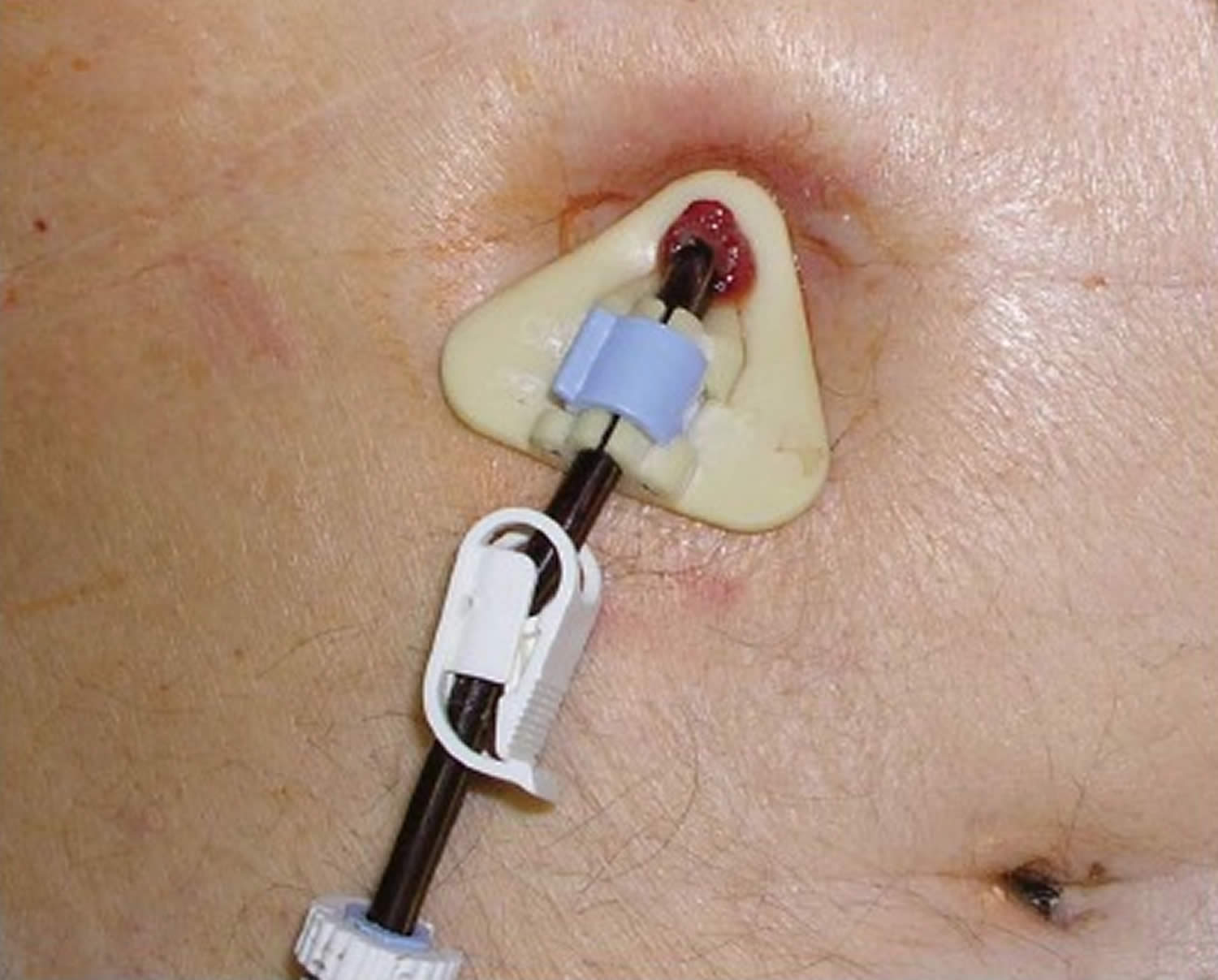

[Source 4 ]Figure 2. Buried bumper syndrome

Footnote: External view demonstrates tight position of the external fixator with peristomal granulations.

[Source 4 ]Buried bumper syndrome causes

Excessive compression of tissue between the external and internal fixation device of the gastrostomy tube is considered the main etiological factor leading to buried bumper syndrome (Figure 2) 7. The optimum position of the external fixator thus plays a key role: excessive pressure can lead to tissue ischemia, necrosis and infection (as the most frequent PEG complication), and subsequent inflammatory and fibrous changes can cause buried bumper syndrome. On the other hand, sufficient interposition of tissue prevents leakage of gastric content into the peritoneal cavity and peritonitis. These two trends are somewhat conflicting: the risk of leakage is considered to be smaller 7 and limited to the first days after PEG introduction, while risk of infection is considerable and risk of buried bumper syndrome is long term. Firm apposition of the external fixator just after introduction with subsequent release within several days seems to be an optimal compromise from this aspect. Chung et al 8 found more complications in a cohort of patients with traction than without. Traction formed a twice as shorter stoma tract and led to complications including fatal fasciitis/myositis, bleeding and buried bumper syndrome, while omitting traction was not complicated by leakage. Stoma tract formation was followed in studies on dogs. Mellinger et al 9 found no complications in a cohort with a loose external fixator. The frequency of infectious complications and buried bumper syndrome correlated with tightness of the external fixator in the study performed by DeLegge et al 10. Swelling of all tissues involved in the stoma tract can further increase the pressure and must be taken into account 11.

Risk factors for buried bumper syndrome

Risk factors for buried bumper syndrome can be classified as follows: (1) cannula (material, shape, and axis deviation); (2) procedure (point of insertion, position of the external fixator, and dressing); (3) long-term care (change of the position of the external fixator, dressing, and preventive maneuvers); and (4) patient (indication, comorbidity, medication, and abnormal manipulation with gastrostomy) 4.

Rigidity and abrasiveness (and change of these properties in an acid gastric environment) can contribute to buried bumper syndrome. Small contact area 7, sharp edges and conical shape pose a risk of buried bumper syndrome. Improper lining, jejunal extension 12 and some types of cannula are prone to deviate the axis from perpendicular to more tangential. The risk of buried bumper syndrome with balloon fixation is smaller but not zero 2. The distance between the external fixator and skin should be 10 mm. Some authors recommend this distance at the time of PEG insertion and without interposed dressing 13, others prefer firmer apposition of the external bolster within the first 4 d to avoid peritoneal leakage 7. Permanent interposition of a dressing or tightening of the external bolster are important risk factors relating to home care 14. There is a higher risk of buried bumper syndrome in patients with malignancy, bad initial nutritional status (body mass index < 20 kg/m²), with significant weight gain 2, in children 7 and uncooperative agitated patients 15. Therapy with systemic corticosteroids or chemo-/radiotherapy can impair tissue healing and forming of the stoma tract.

Although buried bumper syndrome is considered to be a chronic complication[27], migration to skin level was described as early as after 6 days 16 and 9 days 17 from insertion. Acute buried bumper syndrome (within 30 d from insertion) is caused by vigorous traction of the cannula by patients themselves (agitation) 18 or by extreme tightness of the external bolster. These cases are probably not suitable for a conservative and endoscopic approach with respect to the immature stoma tract 19.

Buried bumper syndrome prevention

The most important preventive measure is adequate positioning of the external bolster. The distance between the skin and the external fixator should be 10 mm, although there is no consensus as to whether this distance is safe at the time of insertion (without interposed lining) 20, or whether firmer apposition is needed (for around 4 days) with respect to risk of peritoneal leakage 7. The length of the stoma channel (skin surface level against the scaled cannula) should be measured and recorded at the time of insertion for future reference 7. There is also no consistent opinion about the need for endoscopic control of the internal fixator during the final PEG set assembly 7. There is no doubt as to loose positioning of the external bolster (10 mm) in patients with a mature stoma tract (usually after 2 weeks) 20. The stoma tract lengthens with weight gain and in upright position 7 and the bolster should be properly repositioned.

Movement of the upper limbs in uncooperative patients might be managed using special gloves or using a low-profile device (feeding button) 18. Simple wrapping of the PEG can lead to deviation of the tube axis and can initiate buried bumper syndrome.

“PEG twirl sign” 21 and others. At least basic written information is advisable. Some authors recommend systematic follow-up of all the patients with PEG by a nutritional team 3.

Buried bumper syndrome symptoms

Leakage of gastric content or nutrition from the stoma is an early symptom of buried bumper syndrome. Erythema, purulent secretion and pain are symptoms of local infection. Fixation of the cannula impedes further insertion, while the ability to rotate can be preserved. Blockage of the tube is a late symptom, sometimes initially limited to aspiration (valve type) 22, but preserved patency does not exclude buried bumper syndrome. In rare cases, the internal disc can protrude from the skin or is palpable just below the skin. Inability to insert, loss of patency, and leakage around the PEG tube are considered to be a typical symptomatic triad 23. Buried bumper syndrome can be an incidental finding during gastroscopy for removal or for another indication.

Buried bumper syndrome complications

Buried bumper syndrome can be complicated by gastrointestinal bleeding 24, perforation, peritonitis 25, intra-abdominal 26 and abdominal wall abscesses 27, or phlegmon 28, and these complications can lead to fatal outcomes. Bleeding can be treated endoscopically by epinephrine injection and tamponade with a balloon gastrostomy set 29, but sometimes angiography is needed 24.

Buried bumper syndrome diagnosis

Buried bumper syndrome is diagnosed endoscopically, with raised clinical suspicion in cases of resistance to pushing the tube internally or resistance to rotation of the tube externally 1. Endoscopic examination can initially reveal pressure ulceration beneath the internal bumper, followed by mucosal tissue encroaching and eventually covering the internal bumper. A delay in diagnosis can allow for further outward displacement of the internal bumper, that can be complicated by peritonitis, perforation, and formation of an abscess or a phlegmon 5. Also, the cellulitis some patient developed soon after the initial placement likely contributed to edema and swelling extending beyond the boundaries of the internal bumper to later cover it completely.

A pressure ulcer (Figure 1A) below the disc and tissue growing over the edge of the disc (Figure 1B) are typical early signs. The disc can disappear gradually; the involved area may be flat (Figure 1C), excavated (Figure 1D) or elevated (Figure 1E), resembling a submucosal tumor. The mucosa may be normal or edematous. The orifice of a residual fistula can be identified in the majority of cases; discharge of pus, nutrition, rinsing water (Figure 1E) or methylene blue injected to cannula 30 can reveal it. Localization of the fistula orifice does not always correspond with localization of the buried bumper itself 31, a fluoroscopic “tubogram” can be performed (Figure 3). A guidewire pulled through the PEG and fistula to the stomach lumen can help to guide endoscopic therapy.

The depth of disc migration in relation to the lamina muscularis propria of the stomach is critical for further therapy. The depth of migration can be estimated by endoscopic ultrasound (miniprobe or radial); transabdominal ultrasound was used previously by our group in a small case series 32. Computed tomography (CT) can also help to diagnose buried bumper syndrome 33 and estimate the depth of migration 34, although further methodological data are lacking.

Figure 3. Buried bumper syndrome fluoroscopy (tubogram)

Footnote: Cavity around the buried bolster filled with contrast agent leaking through the fistula (arrow) to the stomach lumen.

[Source 4 ]Buried bumper syndrome treatment

Management of buried bumper syndrome should be individualized, due to lack of consensus on a standardized approach to this rare complication 4. Kejariwal et al. 35 described a “cut and leave it alone” approach in a case series of patients deemed poor surgical candidates, where the PEG-tubes were left in situ and follow-up over 18 months revealed no late complications. A “push and pull inside” approach is described in case series, where the buried bumper is stiffened and pushed inside the stomach after metallic dilators are used to dilate the stoma, followed by endoscopic PEG extraction 4. Müller-Gerbes et al. 36 described removal via the introduction of a papillotome into the stomach through the severed PEG externally, and through dissection of the adjacent fibrous tissue and tract dilatation, the bumper is pushed into the stomach and retrieved endoscopically. In addition, external traction has been reported to be successful in removing the buried internal bumper 37. Nevertheless, surgical removal is occasionally needed after the failure of more conservative modalities 4.

References- Abu-Heija AA, Tama M, Abu-Heija U, Khalid M, Al-Subee O. Delayed Diagnosis of Buried Bumper Syndrome When Only the Jejunostomy Extension is Used in a Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy-jejunostomy Levodopa-carbidopa Intestinal Gel Delivery System. Cureus. 2019;11(4):e4568. Published 2019 Apr 30. doi:10.7759/cureus.4568 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6605971

- Lee TH, Lin JT. Clinical manifestations and management of buried bumper syndrome in patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:580–584.

- El AZ, Arvanitakis M, Ballarin A, Devière J, Le Moine O, Van Gossum A. Buried bumper syndrome: low incidence and safe endoscopic management. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:312–316.

- Cyrany J, Rejchrt S, Kopacova M, Bures J. Buried bumper syndrome: A complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(2):618–627. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.618 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4716063

- Enteral access and associated complications. DeLegge MH. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47:23–37.

- Buried bumper syndrome: a complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Cyrany J, Rejchrt S, Kopacova M, Bures J. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:618–627.

- McClave SA, Jafri NS. Spectrum of morbidity related to bolster placement at time of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: buried bumper syndrome to leakage and peritonitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:731–746.

- Chung RS, Schertzer M. Pathogenesis of complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. A lesson in surgical principles. Am Surg. 1990;56:134–137.

- Mellinger JD, Simon IB, Schlechter B, Lash RH, Ponsky JL. Tract formation following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in an animal model. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:189–191.

- DeLegge M, DeLegge R, Brady C. External bolster placement after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube insertion: is looser better? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30:16–20.

- Dell’Abate P. Buried bumper syndrom: two case reports. Recommendations and management. Personal experience. Acta Endoscopica. 1999;29:513–517.

- Behrle KM, Dekovich AA, Ammon HV. Spontaneous tube extrusion following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:56–58.

- Gastrostomy tubes: Complications and their management. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gastrostomy-tubes-complications-and-their-management

- Gençosmanoğlu R, Koç D, Tözün N. The buried bumper syndrome: migration of internal bumper of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube into the abdominal wall. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1077–1080.

- Kim YS, Oh YL, Shon YW, Yang HD, Lee SI, Cho EY, Choi CS, Seo GS, Choi SC, Na YH. A case of buried bumper syndrome in a patient with a balloon-tipped percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube. Endoscopy. 2006;38 Suppl 2:E41–E42.

- Khalil Q, Kibria R, Akram S. Acute buried bumper syndrome. South Med J. 2010;103:1256–1258.

- E Boldo, G Perez de Lucia, J Aracil, F Martin, D Martinez, J Miralles, A Armelles. Early Buried Bumper Syndrome. The Internet Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006 Volume 5 Number 1. http://ispub.com/IJGE/5/1/7732

- Rino Y, Tokunaga M, Morinaga S, Onodera S, Tomiyama I, Imada T, Takanashi Y. The buried bumper syndrome: an early complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1183–1184.

- Anagnostopoulos GK, Kostopoulos P, Arvanitidis DM. Buried bumper syndrome with a fatal outcome, presenting early as gastrointestinal bleeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:325–327.

- Itkin M, DeLegge MH, Fang JC, McClave SA, Kundu S, d’Othee BJ, Martinez-Salazar GM, Sacks D, Swan TL, Towbin RB, et al. Multidisciplinary practical guidelines for gastrointestinal access for enteral nutrition and decompression from the Society of Interventional Radiology and American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, with endorsement by Canadian Interventional Radiological Association (CIRA) and Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) Gastroenterology. 2011;141:742–765.

- )Boyd JW, DeLegge MH, Shamburek RD, Kirby DF. The buried bumper syndrome: a new technique for safe, endoscopic PEG removal. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:508–511.) is an important preventive measure. Once the stoma channel has matured (usually after 2 weeks), the external bolster should be unfastened once weekly (some authors recommend daily) and a PEG tube inserted several centimeters inside and turned 360° around its long axis. The external fixator should be fastened back to the proper (loose) position. This maneuver is not suitable for balloon catheters and for PEG with jejunal extension.

Communication among all involved subjects is the key issue in PEG care: patients, relatives, nurses, home-care facilities, nursing home staff, the digestive endoscopist, nutritional specialist, biomedical companies ((Sheers R, Chapman S. The buried bumper syndrome: a complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gut. 1998;43:586.

- Köhler H, Lang T, Behrens R. Buried bumper syndrome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children and adolescents. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E85–E86.

- Nelson AM. PEG feeding tube migration and erosion into the abdominal wall. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:133.

- Van Weyenberg SJ, Lely RJ. Arterial hemorrhage due to a buried percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy catheter. Endoscopy. 2013;45 Suppl 2 UCTN:E261–E262.

- Finocchiaro C, Galletti R, Rovera G, Ferrari A, Todros L, Vuolo A, Balzola F. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a long-term follow-up. Nutrition. 1997;13:520–523.

- Walters G, Ramesh P, Memon MI. Buried Bumper Syndrome complicated by intra-abdominal sepsis. Age Ageing. 2005;34:650–651.

- Johnson T, Velez KA, Zhan E. Buried bumper syndrome causing rectus abdominis necrosis in a man with tetraplegia. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:85–86.

- Biswas S, Dontukurthy S, Rosenzweig MG, Kothuru R, Abrol S. Buried bumper syndrome revisited: a rare but potentially fatal complication of PEG tube placement. Case Rep Crit Care. 2014;2014:634953.

- Dormann AJ, Müssig O, Wejda B, Huchzermeyer H. [Successful use of a button system in “buried bumper” syndrome] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2001;126:722–724.

- Oner OZ, Gündüz UR, Koç U, Karakas BR, Harmandar FA, Bülbüller N. Management of a complicated buried bumper syndrome with a technique involving dye test, cannulation, and extraction. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E238–E239.

- Hodges EG, Morano JU, Nowicki MJ. The buried bumper syndrome complicating percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33:326–328.

- Elbaz T, Douda T, Cyrany J, Repak R, Bures J. Buried bumper syndrome: an uncommon complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Report of three cases. Folia Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:61–66.

- Larson DE, Burton DD, Schroeder KW, DiMagno EP. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Indications, success, complications, and mortality in 314 consecutive patients. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:48–52.

- Hwang JH, Kim HW, Kang DH, Choi CW, Park SB, Park TI, Jo WS, Cha DH. A case of endoscopic treatment for gastrocolocutaneous fistula as a complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:95–98.

- Buried bumper syndrome: cut and leave it alone! Kejariwal D, Aravinthan A, Bromley D, Miao Y. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23:322–324.

- Management of the buried bumper syndrome: a new minimally invasive technique – the push method. (Article in German) Müller-Gerbes D, Aymaz S, Dormann A. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:1145–1148.

- Gastroenteric tube feeding: techniques, problems and solutions. Blumenstein I, Shastri YM, Stein J. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8505–8524.