Extrapyramidal symptoms

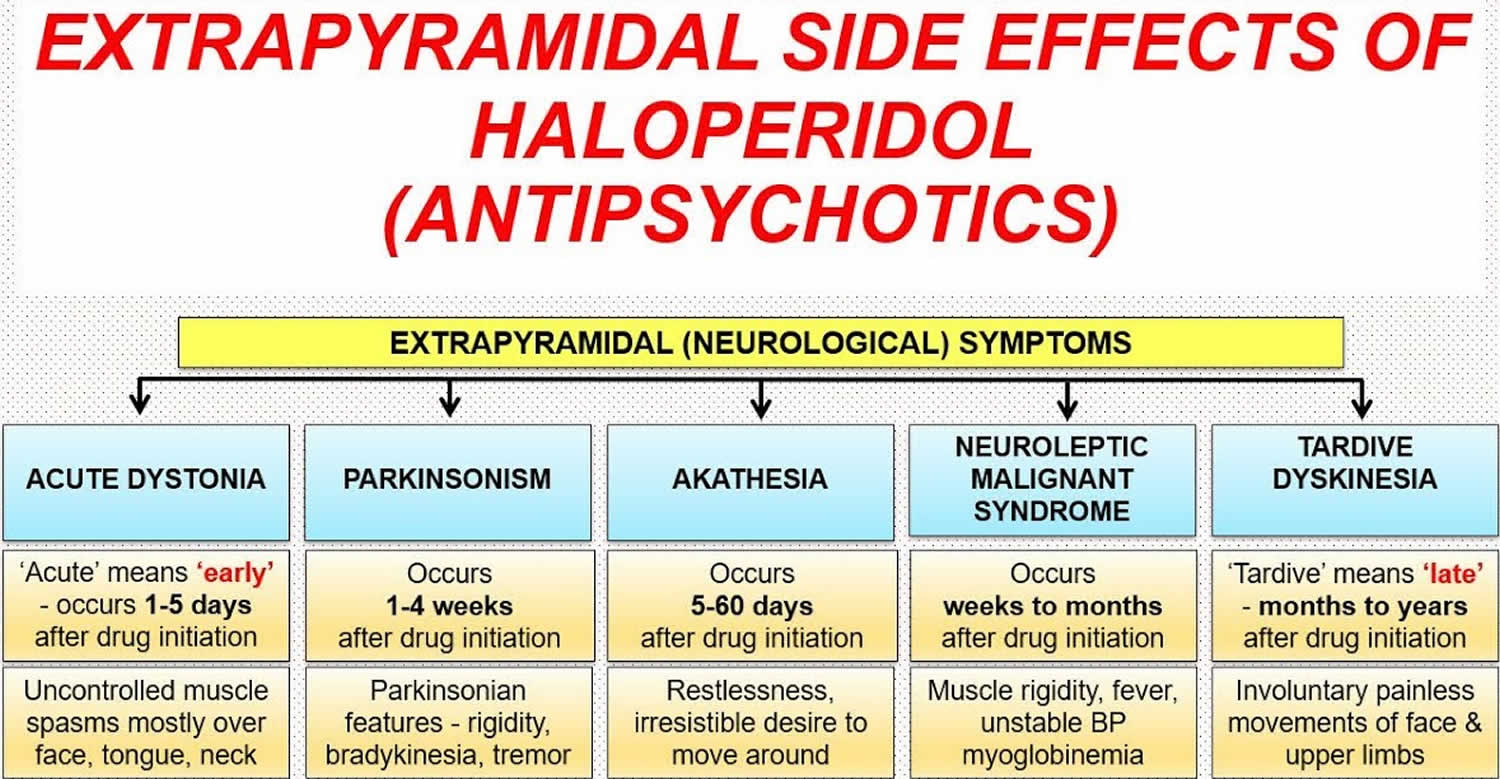

Extrapyramidal symptoms also known as extrapyramidal side effects, include acute dyskinesias, dystonia, tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonism, akinesia, akathisia, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome 1. Extrapyramidal symptoms are commonly referred to as drug-induced movement disorders are among the most common drug side effects from dopamine-receptor blocking agents 2. Less recognized is that extrapyramidal symptoms are also associated with certain non-antipsychotic agents, including some antidepressants, lithium, various anticonvulsants, antiemetics and rarely, oral-contraceptive agents 1. Extrapyramidal symptoms caused by these agents are indistinguishable from neuroleptic-induced extrapyramidal symptoms. Clinicians must be able to recognize these side effects and be able to determine the antipsychotic-induced and non-antipsychotic causes of extrapyramidal symptoms.

Extrapyramidal symptoms was first described in 1952 after chlorpromazine-induced symptoms resembling Parkinson disease 3. A variety of movement phenotypes has since been described along the extrapyramidal side effects spectrum, including dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism, which occur more acutely, as well as more chronic manifestations of tardive akathisia and tardive dyskinesia. The symptoms of extrapyramidal side effects are debilitating, interfering with social functioning and communication, motor tasks, and activities of daily living. This is often associated with poor quality of life and abandonment of therapy, which may result in disease relapse and re-hospitalization, particularly in schizophrenic patients stopping pharmacologic therapy 4.

Rates of extrapyramidal side effects are dependent on the class of medication administered. First-generation neuroleptics were associated with extrapyramidal side effects in 61.6% of patients in a study of institutionalized patients with schizophrenia 5. Rates of extrapyramidal side effects have declined with atypical antipsychotics with clozapine having the lowest risk and risperidone the highest 6. In terms of antiemetics with a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist effect, extrapyramidal side effects incidence is cited to be between 4% to 25% with metoclopramide 7 and between 25% to 67% with prochlorperazine 8.

Extrapyramidal symptoms causes

Centrally-acting, dopamine-receptor blocking agents, namely the first-generation antipsychotics haloperidol and phenothiazine neuroleptics, are the most common medications associated with extrapyramidal side effects 2. While extrapyramidal side effects occurs less frequently with atypical antipsychotics, the risk of extrapyramidal side effects increases with dose escalation 9. Other agents that block central dopaminergic receptors have also been identified as causative of extrapyramidal side effects, including antiemetics (metoclopramide, droperidol, and prochlorperazine) 10, lithium 11, serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) 12, stimulants 13 and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) 12. In rare situations, antivirals, antiarrhythmics, and valproic acid have also been implicated 14.

Risks factors include a history of prior extrapyramidal side effects and high medication dose 15. Elderly females are more susceptible to drug-induced parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia 16, while young males manifest with more dystonic reactions 17.

The mechanism of extrapyramidal side effects is thought to be due to the antagonistic binding of dopaminergic D2 receptors within the mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways of the brain. However, the antidopaminergic action in the caudate nucleus and other basal ganglia may also contribute significantly to the occurrence of extrapyramidal side effects 18.

Researchers previously hypothesized that the faster dissociation of atypical antipsychotics from the dopamine receptor, compared to typical antipsychotics, explained the reduced incidence of extrapyramidal side effects. However, a recent study by Sykes utilized a novel time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer assay to demonstrate that binding kinetics and association rates, not dissociation, correlate more with extrapyramidal side effects 19.

Extrapyramidal side effects prevention

Studies investigating the administration of prophylactic anticholinergic medications to prevent or reduce extrapyramidal side effects have been performed. Authors 20 have cautioned that prophylactic anticholinergic medications have distressing peripheral side-effects, including dry mouth, urinary disturbances, and constipation, as well as undesirable central effects comprising cognitive dysfunction and delirium. This long-term prophylactic administration of anticholinergic medications in schizophrenia patients taking antipsychotics may worsen underlying cognitive impairment and subsequently worsen the quality of life 20. Thus, while current guidelines generally do not recommend the prophylactic or long-term use of anticholinergics in schizophrenic patients taking antipsychotics, this decision should be made on a case-by-case basis with meticulous risk-benefit analysis. In the emergency medicine realm, a meta-analysis demonstrated that prophylactic diphenhydramine reduces extrapyramidal side effects in patients receiving bolus administration of antiemetic (with a dopamine D2 antagonist effect), but not when the antiemetic was given as an infusion; thus, this meta-analysis concluded that the most effective strategy would be to administer the antiemetic as an infusion without anticholinergic prophylaxis.

Extrapyramidal side effects symptoms

There is a wide spectrum of extrapyramidal side effects presentations, some extrapyramidal side effects is distressing, especially with painful torticollis, oculogyric crisis, and bulbar type of speech. If left untreated, it may cause dehydration, infection, pulmonary embolism, rhabdomyolysis, respiratory stridor, and obstruction 10.

Dystonia most often occurs within 48 hours of drug exposure in 50% of cases, and within five days in 90% of cases 21. On physical exam, dystonia manifests with involuntary muscle contractions resulting in abnormal posturing or repetitive movements. It may affect muscles in different body parts, including the back and extremities (opisthotonus), neck (torticollis), jaw (trismus), eyes (oculogyric crisis), abdominal wall, and pelvic muscles (tortipelvic crisis), and facial and tongue muscles (buccolingual crisis) 22. The provider must evaluate these patients for pain and particularly difficulty in breathing, swallowing, and speech.

Akathisia is characterized by a subjective feeling of internal restlessness and a compelling urge to move, leading to the objective observation of repetitive movements comprising leg crossing, swinging, or shifting from one foot to another 16. The onset is usually within four weeks of starting or increasing the dosage of the offending medication. Due to its often vague and non-specific presentation of nervousness and discomfort, akathisia is often misdiagnosed as anxiety, restless leg syndrome, or agitation. In an attempt to treat these incorrect diagnoses, the provider may subsequently increase anti-psychotic or SSRI medications, further exacerbating akathisia 16. This failure to correctly diagnose can be detrimental as the severity of akathisia is linked to suicidal ideation, aggression, and violence 23. Healthcare provider must also note that withdrawal akathisia may occur with discontinuation or dose reduction of antipsychotic medication, and is typically self-limited lasting within six weeks 16.

Drug-induced parkinsonism presents as tremor, rigidity, and slowing of motor function in the truncal region and extremities. The classic appearance is an individual with masked facies, stooped posture, and a slow shuffling gait. Gait imbalance and difficulty rising from a seated position are often noted 14.

Finally, tardive dyskinesia manifests as involuntary choreoathetoid movements affecting orofacial and tongue muscles, and less commonly the truncal region and extremities. While symptoms are typically not painful, they may impede social interaction and cause difficulty in chewing, swallowing, and talking 24.

Extrapyramidal side effects complications

Antipsychotic-induced and metoclopramide-induced laryngeal dystonia has been reported predominantly in young males 25. Rhabdomyolysis is a rare complication of drug-induced dystonia, especially if prolonged dystonia is present 26. While dystonic storm typically occurs in patients with primary known dystonia (e.g., Wilson disease, DYT1 dystonia), triggers typically include infection and medication adjustment in a significant number of cases 27. A dystonic storm is a life-threatening situation that manifests with fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypertensive crisis, diaphoresis, dysphagia, and respiratory failure 27. The manifestation of extrapyramidal side effects in schizophrenic patients is associated with poor compliance with other atypical antipsychotic medications, which may subsequently lead to a relapse of schizophrenia and hospitalization 4. Failure to correctly diagnose and treat extrapyramidal side effects is linked to suicidal ideation, aggression, and violence 23.

Extrapyramidal symptoms diagnosis

In most cases, laboratory and imaging tests are not required. The diagnosis is apparent from an accurate history and physical exam, especially noting a history of medication exposure.

Extrapyramidal symptoms differential diagnosis

Extrapyramidal side effects may be challenging to distinguish from other idiopathic movement disorders. Muscle rigidity and tension are nonspecific symptoms that may be observed in neuroleptic malignant syndrome, serotonin syndrome, and other movement disorders. Chorea and athetosis are also present in Huntington disease (distinguished based on family history and genetic testing), Sydenham chorea (identified with a history of streptococcal infection), Wilson disease (adolescent-onset with a defect in copper metabolism), and cerebrovascular lesions 28. The flat facial expression, psychomotor slowing, and low energy level in akathisia may mimic the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. In addition, restlessness in akathisia may also appear similar to anxiety and psychotic agitation 29. If dementia accompanies parkinsonian signs and other motor abnormalities, the provider should evaluate the patient for Parkinson disease, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia 28. Interestingly, up to a third of new-onset schizophrenic patients who have never been medicated may present with parkinsonian signs 30.

Extrapyramidal symptoms treatment

If a patient is experiencing acute onset of extrapyramidal side effects, particularly dystonia, healthcare provider must assess if an emergency airway intervention is necessary as laryngeal and pharyngeal dystonic reactions may increase the risk of imminent respiratory arrest 2. Dystonic reactions are rarely life-threatening, and healthcare provider should discontinue the offending agent and manage pain if present. If the causative medication is a typical first-generation antipsychotic, switching to an atypical antipsychotic may be trialed. Administration of an antimuscarinic agent (benztropine, trihexyphenidyl) or diphenhydramine may relieve dystonia within minutes 18. In cases of tardive dystonia, additional therapeutic strategies include administration of benzodiazepine 18, injection of botulinum toxin for facial dystonia 31, trial of muscle relaxant (e.g., baclofen) 31, trial of dopamine-depleting agents (e.g. tetrabenazine),[30] and consideration of deep-brain stimulation or pallidotomy for refractory cases 31.

For the treatment of akathisia, strategies similar to managing dystonia are employed, including stopping or reducing the dosage of the offending medication, switching to an atypical antipsychotic if a typical first-generation antipsychotic was the offending drug, and administering anti-muscarinic agents. Additional therapeutic strategies more specific to akathisia include administration of a beta-blocker (most commonly propranolol), amantadine, clonidine, benzodiazepines, mirtazapine, mianserin (tetracyclic antidepressant), cyproheptadine, and propoxyphene 32.

Tardive dyskinesia is treated by withdrawal or dose reduction of the causative medication, switching to an atypical antipsychotic, withdrawal of concurrent antimuscarinic medications (although trihexyphenidyl has been reported to be therapeutic) 33, injection of botulinum toxin for facial dyskinesia 34, benzodiazepines 35, amantadine 35, and trial of dopamine-depleting medications (e.g. tetrabenazine) 36. Interestingly, the trial of levetiracetam, zonisamide, pregabalin, vitamin B6, and vitamin E have also been reported as therapeutic 24.

Drug-induced parkinsonism is treated with discontinuation or dose reduction of the causative medication, switching to an atypical antipsychotic, and administration of medications used for Parkinson disease, including amantadine, antimuscarinic agents, dopamine agonists, and levodopa 37.

Extrapyramidal symptoms prognosis

Extrapyramidal side effects typically resolve spontaneously or improve with pharmacologic interventions. Acute dystonic reactions are often transient, but late-onset and persistent tardive dystonia have been described in the literature where symptoms persisted for years 38. A study of 107 cases of tardive dystonia reported that only 14% of patients achieved remission over a mean follow-up period of 8.5 years 39. Similarly, while acute akathisia may spontaneously resolve or improve with appropriate medication, studies have reported cases of tardive akathisia persisting over many years 40. Tardive dyskinesia also persists chronically with a cumulative persistence rate as high as 82% in a study of patients with schizophrenia 41.

While some drug-induced movement disorders may last a few minutes, others may last long-term for weeks to years, and may potentially lead to contractures, bony deformities, or significant motor impairment. Physical medicine and rehabilitation consultation may provide useful treatment modalities that have shown efficacy in alleviating dystonia, including relaxation training, biofeedback, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and percutaneous dorsal column stimulation 42. Physical and occupational therapy is paramount, leading to improvement in gait and mobility. In patients with oromandibular or laryngeal involvement, speech therapy may assist with dysphagia and communication barriers. In presentations of extrapyramidal side effects refractory to pharmacologic management, neurosurgical consultation may be beneficial to explore deep brain stimulation, thalamotomy, and pallidotomy.

References- Extrapyramidal symptoms are serious side-effects of antipsychotic and other drugs. Nurse Pract. 1992 Nov;17(11):56, 62-4, 67. DOI:10.1097/00006205-199211000-00018

- D’Souza RS, Hooten WM. Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS) [Updated 2019 Nov 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534115

- Rifkin A. Extrapyramidal side effects: a historical perspective. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987 Sep;48 Suppl:3-6.

- Frances A, Weiden P. Promoting compliance with outpatient drug treatment. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1987 Nov;38(11):1158-60.

- Janno S, Holi M, Tuisku K, Wahlbeck K. Prevalence of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders in chronic schizophrenia inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Jan;161(1):160-3.

- Divac N, Prostran M, Jakovcevski I, Cerovac N. Second-generation antipsychotics and extrapyramidal adverse effects. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:656370.

- Parlak I, Erdur B, Parlak M, Ergin A, Turkcuer I, Tomruk O, Ayrik C, Ergin N. Intravenous administration of metoclopramide by 2 min bolus vs 15 min infusion: does it affect the improvement of headache while reducing the side effects? Postgrad Med J. 2007 Oct;83(984):664-8.

- Saadah HA. Abortive headache therapy in the office with intravenous dihydroergotamine plus prochlorperazine. Headache. 1992 Mar;32(3):143-6.

- Farah A. Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(6):268-74.

- D’Souza RS, Mercogliano C, Ojukwu E, D’Souza S, Singles A, Modi J, Short A, Donato A. Effects of prophylactic anticholinergic medications to decrease extrapyramidal side effects in patients taking acute antiemetic drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2018 May;35(5):325-331.

- Kane J, Rifkin A, Quitkin F, Klein DF. Extrapyramidal side effects with lithium treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1978 Jul;135(7):851-3.

- Madhusoodanan S, Alexeenko L, Sanders R, Brenner R. Extrapyramidal symptoms associated with antidepressants–a review of the literature and an analysis of spontaneous reports. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010 Aug;22(3):148-56.

- Asser A, Taba P. Psychostimulants and movement disorders. Front Neurol. 2015;6:75.

- Bohlega SA, Al-Foghom NB. Drug-induced Parkinson`s disease. A clinical review. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2013 Jul;18(3):215-21.

- Hedenmalm K, Güzey C, Dahl ML, Yue QY, Spigset O. Risk factors for extrapyramidal symptoms during treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, including cytochrome P-450 enzyme, and serotonin and dopamine transporter and receptor polymorphisms. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006 Apr;26(2):192-7.

- Salem H, Nagpal C, Pigott T, Teixeira AL. Revisiting Antipsychotic-induced Akathisia: Current Issues and Prospective Challenges. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):789-798.

- Kondo T, Otani K, Tokinaga N, Ishida M, Yasui N, Kaneko S. Characteristics and risk factors of acute dystonia in schizophrenic patients treated with nemonapride, a selective dopamine antagonist. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999 Feb;19(1):45-50.

- Kamin J, Manwani S, Hughes D. Emergency psychiatry: extrapyramidal side effects in the psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv. 2000 Mar;51(3):287-9.

- Sykes DA, Moore H, Stott L, Holliday N, Javitch JA, Lane JR, Charlton SJ. Extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotics are linked to their association kinetics at dopamine D2 receptors. Nat Commun. 2017 Oct 02;8(1):763.

- Ogino S, Miyamoto S, Miyake N, Yamaguchi N. Benefits and limits of anticholinergic use in schizophrenia: focusing on its effect on cognitive function. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014 Jan;68(1):37-49.

- Pasricha PJ, Pehlivanov N, Sugumar A, Jankovic J. Drug Insight: from disturbed motility to disordered movement–a review of the clinical benefits and medicolegal risks of metoclopramide. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Mar;3(3):138-48.

- Low LC, Goel KM. Metoclopramide poisoning in children. Arch. Dis. Child. 1980 Apr;55(4):310-2.

- Lipinski JF, Mallya G, Zimmerman P, Pope HG. Fluoxetine-induced akathisia: clinical and theoretical implications. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989 Sep;50(9):339-42.

- Cornett EM, Novitch M, Kaye AD, Kata V, Kaye AM. Medication-Induced Tardive Dyskinesia: A Review and Update. Ochsner J. 2017 Summer;17(2):162-174.

- Christodoulou C, Kalaitzi C. Antipsychotic drug-induced acute laryngeal dystonia: two case reports and a mini review. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 2005 May;19(3):307-11.

- Cavanaugh JJ, Finlayson RE. Rhabdomyolysis due to acute dystonic reaction to antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984 Aug;45(8):356-7.

- Termsarasab P, Frucht SJ. Dystonic storm: a practical clinical and video review. J Clin Mov Disord. 2017;4:10.

- Sanders RD, Gillig PM. Extrapyramidal examinations in psychiatry. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012 Jul;9(7-8):10-6.

- Kane JM. Extrapyramidal side effects are unacceptable. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001 Oct;11 Suppl 4:S397-403.

- Peralta V, Basterra V, Campos MS, de Jalón EG, Moreno-Izco L, Cuesta MJ. Characterization of spontaneous Parkinsonism in drug-naive patients with nonaffective psychotic disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012 Mar;262(2):131-8.

- Cloud LJ, Jinnah HA. Treatment strategies for dystonia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010 Jan;11(1):5-15.

- Inada T. [Drug-Induced Akathisia]. Brain Nerve. 2017 Dec;69(12):1417-1424.

- Kang UJ, Burke RE, Fahn S. Natural history and treatment of tardive dystonia. Mov. Disord. 1986;1(3):193-208.

- Alabed S, Latifeh Y, Mohammad HA, Rifai A. Gamma-aminobutyric acid agonists for neuroleptic-induced tardive dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Apr 13;(4):CD000203

- Waln O, Jankovic J. An update on tardive dyskinesia: from phenomenology to treatment. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2013;3

- Kenney C, Jankovic J. Tetrabenazine in the treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006 Jan;6(1):7-17.

- Shin HW, Chung SJ. Drug-induced parkinsonism. J Clin Neurol. 2012 Mar;8(1):15-21.

- Burke RE, Fahn S, Jankovic J, Marsden CD, Lang AE, Gollomp S, Ilson J. Tardive dystonia: late-onset and persistent dystonia caused by antipsychotic drugs. Neurology. 1982 Dec;32(12):1335-46.

- Kiriakakis V, Bhatia KP, Quinn NP, Marsden CD. The natural history of tardive dystonia. A long-term follow-up study of 107 cases. Brain. 1998 Nov;121 ( Pt 11):2053-66.

- Burke RE, Kang UJ, Jankovic J, Miller LG, Fahn S. Tardive akathisia: an analysis of clinical features and response to open therapeutic trials. Mov. Disord. 1989;4(2):157-75.

- Tenback DE, van Harten PN, Slooff CJ, van Os J. Incidence and persistence of tardive dyskinesia and extrapyramidal symptoms in schizophrenia. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 2010 Jul;24(7):1031-5.

- Cho HJ, Hallett M. Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation for Treatment of Focal Hand Dystonia: Update and Future Direction. J Mov Disord. 2016 May;9(2):55-62.