Adrenal cortical carcinoma

Adrenocortical carcinoma also called cancer of the adrenal cortex or adrenal cortical carcinoma, is a very rare cancer in which cancer cells form in the outer layer of your adrenal gland 1, 2. The outer layer of your adrenal gland is called the adrenal cortex (Figures 1 and 2). Cancer that forms in the adrenal medulla is called pheochromocytoma and is not discussed here in this article. You have 2 adrenal glands and one adrenal gland is located on top of each kidney. Your adrenal glands are responsible for releasing different classes of hormones. The adrenal cortex makes important hormones that:

- Balance the water and salt in your body.

- Help keep your blood pressure normal.

- Help control your body’s use of protein, fat, and carbohydrates.

- Cause your body to have masculine or feminine characteristics.

Adrenal cortical carcinoma is most common in children younger than 5 years old (median age 3–4 years) and adults in their 40s and 50s 3, 4, 5. Childhood adrenal cortical carcinoma typically present during the first 5 years of life (median age 3–4 years), although there is a second, smaller peak during adolescence 6, 7, 8. Both men and women can also develop adrenocortical carcinoma. Female sex is consistently predominant in most studies, with a female to male ratio of 1.6:1.0 5, 7, 8.

Adrenal cortical carcinomas are rare tumors with an annual incidence of 0.7–2.0 cases per million 9, 10. In children, 25 new adrenal cortical carcinoma cases are expected to occur annually in the United States 11. In southern Brazil, adrenal cortical carcinoma is approximately 10 to 15 times higher than that observed in the United States 12, 13, 14, 15.

Adrenocortical carcinoma may develop by chance alone (sporadic), but at least 50% of adrenal cortical carcinoma are thought to be linked to a cancer syndrome that is passed down through families (inherited) 16. The most common syndromes that are associated with adrenocortical carcinoma are Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53 gene germline and somatic mutation), Lynch syndrome (MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM genes), multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1 gene), Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (11p151 gene, IGF-2 overexpression), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP gene, β catenin somatic mutations), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1 gene), Gardner’s syndrome and Carney complex (protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1A [PRKARIA] gene) 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25. Although extremely rare, adrenocortical carcinomas have also been reported in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and myelolipoma 26, 27, 28. It is likely these are collision tumors rather than having been etiologically related 29.

There are a number of genes that have mutations that can cause sporadic adrenocortical carcinoma, including tumor protein 53 (TP53, p53), insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) and β-catenin (CTNNB1 or ZNRF3) 30, 31, 32. Tumor protein 53 (TP53, p53) is a protein product of tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 17 (17p13.1) 33. According to genomic analyses, germline mutations in TP53 were observed in 50–80% of children with sporadic adrenocortical carcinoma, while somatic TP53 mutation was observed in 20% to 30% of sporadic adrenocortical carcinoma patients where it correlates with poor outcome 34. In immunohistochemical studies diffuse TP53 staining correlates positively with increased Ki-67 expression 35.

There have been reports of both autosomal dominant inheritance and autosomal recessive inheritance.

Symptoms of adrenocortical carcinoma may include pain in your abdomen or back, a lump in your abdomen or a feeling of fullness in your abdomen.

Adrenocortical carcinoma can be classified into functioning and nonfunctioning tumors by clinical and biochemical assessment. Approximately 60% of adrenocortical carcinomas produce hormones 36. Nonfunctional adrenocortical carcinomas are rare (<10%) and tend to occur in older children 5.

Adrenocortical carcinomas in children are almost universally functional, they cause endocrine disturbances, and a diagnosis is usually made 5 to 8 months after the first signs and symptoms emerge 5, 6. Nonfunctional adrenocortical carcinomas are rare (<10%) and tend to occur in older children 5.

A functioning adrenal cortical carcinoma makes too much of one of the following hormones, as well as other hormones 37:

- Cortisol. Too much cortisol may cause problem known as Cushing syndrome:

- Weight gain in the face, neck, and trunk of the body and thin arms and legs.

- Growth of fine hair on the face, upper back, or arms.

- A round, red, full face (moon face).

- Fat deposits behind the neck and shoulders (fatty hump or buffalo hump)

- A deepening of the voice and swelling of the sex organs or breasts in both males and females.

- Purple stretch marks on your abdomen

- Muscle weakness and loss of muscle mass in your legs.

- Weakened bones (osteoporosis), which can lead to fractures

- High blood sugar levels, often leading to diabetes

- High blood pressure

- Easy bruising

- Depression and/or moodiness

- Menstrual irregularities in women.

- Aldosterone. Too much aldosterone may cause:

- High blood pressure.

- Low blood potassium levels

- Muscle weakness or cramps.

- Frequent urination.

- Feeling thirsty.

- Testosterone. Men who make too much testosterone do not usually have signs or symptoms. However, too much testosterone in women may cause:

- Growth of fine hair on the face, upper back, or arms.

- Acne.

- Balding.

- A deepening of the voice.

- No menstrual periods.

- Estrogen (female-type hormone).

- Too much estrogen in women may cause:

- Irregular menstrual periods in women who have not gone through menopause.

- Vaginal bleeding in women who have gone through menopause.

- Weight gain.

- Too much estrogen in men may cause:

- Growth of breast tissue.

- Lower sex drive.

- Impotence.

- Too much estrogen in women may cause:

These signs and symptoms may be caused by adrenocortical carcinoma or by other conditions. Check with your doctor if you have any of these problems.

Doctors diagnose adrenocortical carcinoma using imaging studies and tests that examine your blood and urine. An adrenocortical carcinoma is usually diagnosed based on urine tests for abnormal levels of cortisol, the hormone released by the adrenal glands. Blood tests can also be conducted to measure levels of potassium and sodium in your blood. A CT scan or MRI may be used to search for a visible tumor in the adrenal cortex.

Adrenal cortical carcinoma can spread to your liver, bone, lung, or other areas. Adrenocortical carcinoma can recur (come back) after it has been treated. The cancer may come back in the adrenal cortex or in other parts of the body.

The main treatment for adrenal cortical carcinoma is surgery to remove the tumor. You may get medicines (i.e., ketoconazole and metyrapone) to reduce production of cortisol, which causes many of your symptoms.

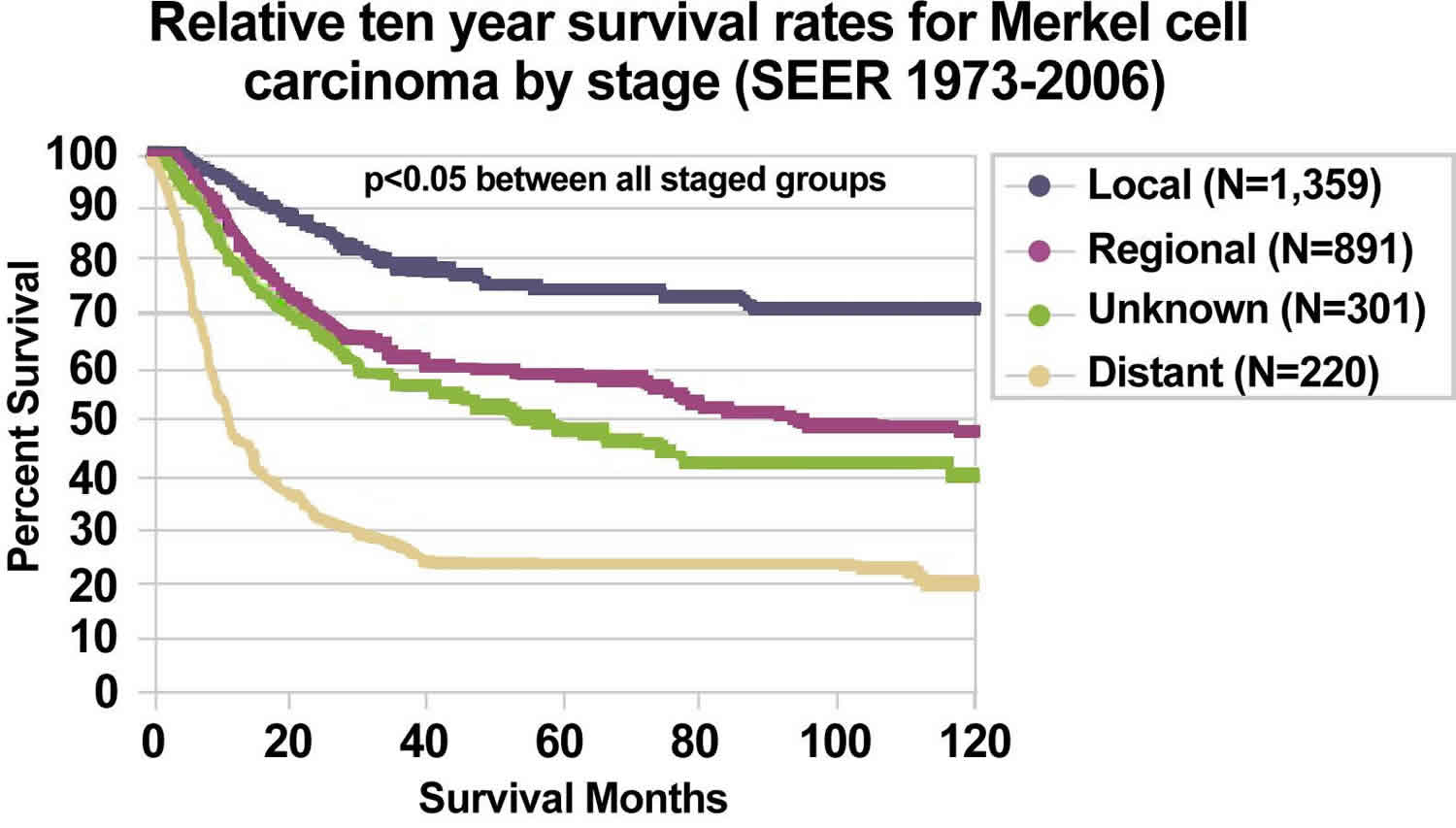

The prognosis (outlook) of adrenal cortical carcinomas varies: resectable tumors have a good prognosis, while metastatic and unresectable tumors have a poor prognosis 38. Overall the prognosis of adrenal cortical carcinoma is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 40% 10, 39. Up to 70% of patients with the localized adrenal cortical carcinoma based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor, Node, and Metastases (TNM) staging system experienced recurrence within 3 years after surgery 39, while the survival duration of patients with metastatic adrenal cortical carcinomas or adrenal cortical carcinoma that has spread ranges from several months to 10 years or more 40, 41, 42.

Can adrenal cortical carcinoma be found early?

It is hard to find adrenal cancers early, and they are often quite large by the time they are diagnosed.

Adrenal cancers are often found earlier in children than in adults because cancers in children are more likely to secrete hormones that lead to signs and symptoms. For example, children may develop signs of puberty at an early age due to sex hormones made by adrenal cancer cells.

Adrenocortical carcinoma are sometimes found early by accident in adults, such as when a CT (computed tomography) scan of the abdomen is done for some other health concern.

Adrenal glands

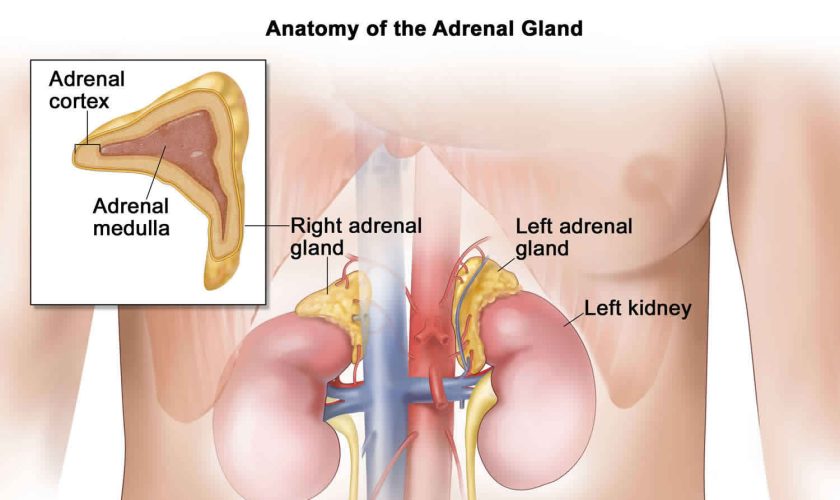

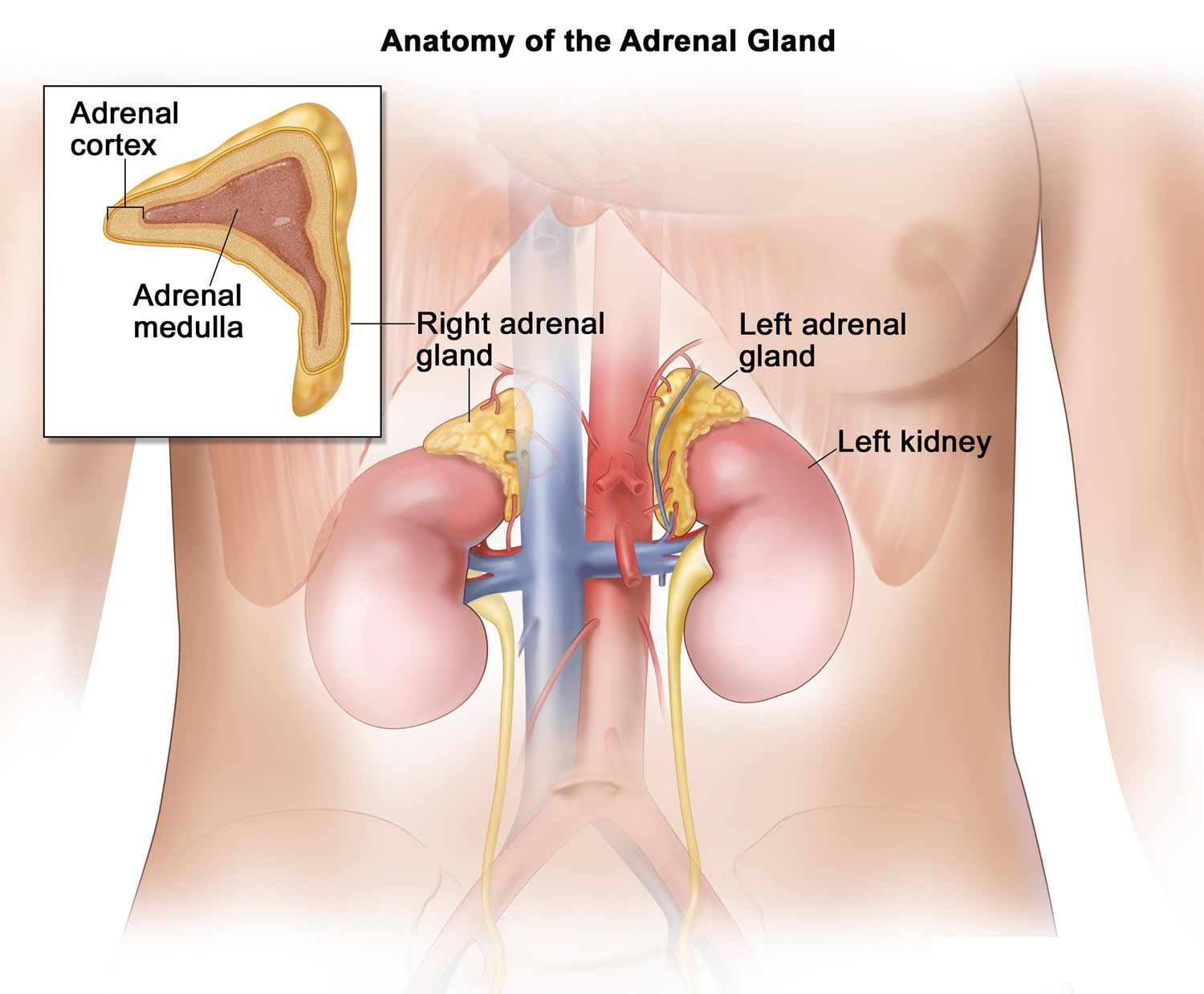

The adrenal glands are two two triangle-shaped glands that measure about 1.5 inches in height and 3 inches in length. They are located on top of each kidney like a cap and is embedded in the mass of fatty tissue that encloses the kidney (Figure 1 and 2). Their name directly relates to their location (ad—near or at; renes—kidneys) 43.

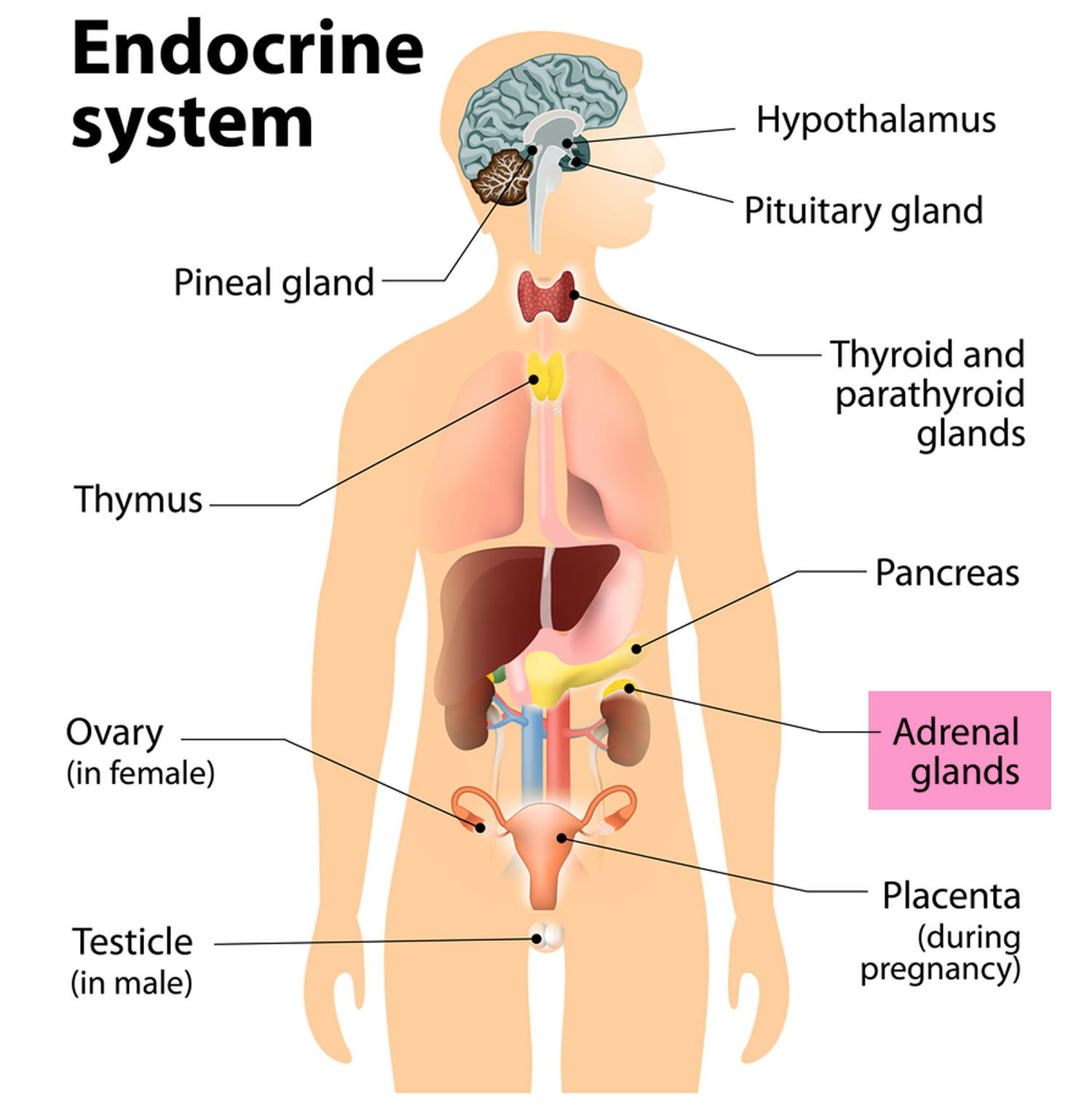

The adrenal glands, located on the top of each kidney, are responsible for releasing different classes of hormones.

The outer part of the adrenal gland, called the adrenal cortex, produces the hormones cortisol, aldosterone, and hormones that can be changed into testosterone 43. The inner part of the gland, called the adrenal medulla, produces the hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline. These hormones are also called epinephrine and norepinephrine 43.

These hormones—cortisol, aldosterone, adrenaline, and noradrenaline—control many important functions in the body, including:

- Maintaining metabolic processes, such as managing blood sugar levels and regulating inflammation.

- Regulating the balance of salt and water.

- Controlling the “fight or flight” response to stress.

- Maintaining pregnancy.

- Initiating and controlling sexual maturation during childhood and puberty.

The adrenal glands are also an important source of sex steroids, such as estrogen and testosterone.

When the adrenal glands produce more or less hormones than normal, you can become sick. This might happen at birth or later in life 44.

The adrenal glands can be affected by many diseases, such as autoimmune disorders, infections, tumors, and bleeding 44.

Conditions related to adrenal gland problems include:

- Addison disease (also called adrenal insufficiency)

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Cushing syndrome

- Diabetes – caused by another medical problem

- Glucocorticoid medicines

- Excessive or unwanted hair in women (hirsutism)

- Hump behind shoulders (dorsocervical fat pad)

- Hypoglycemia

- Primary aldosteronism (Conn syndrome)

- Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome

Location of adrenal glands

Figure 1. Location of the adrenal glands on top of each kidneys

Structure of the adrenal glands

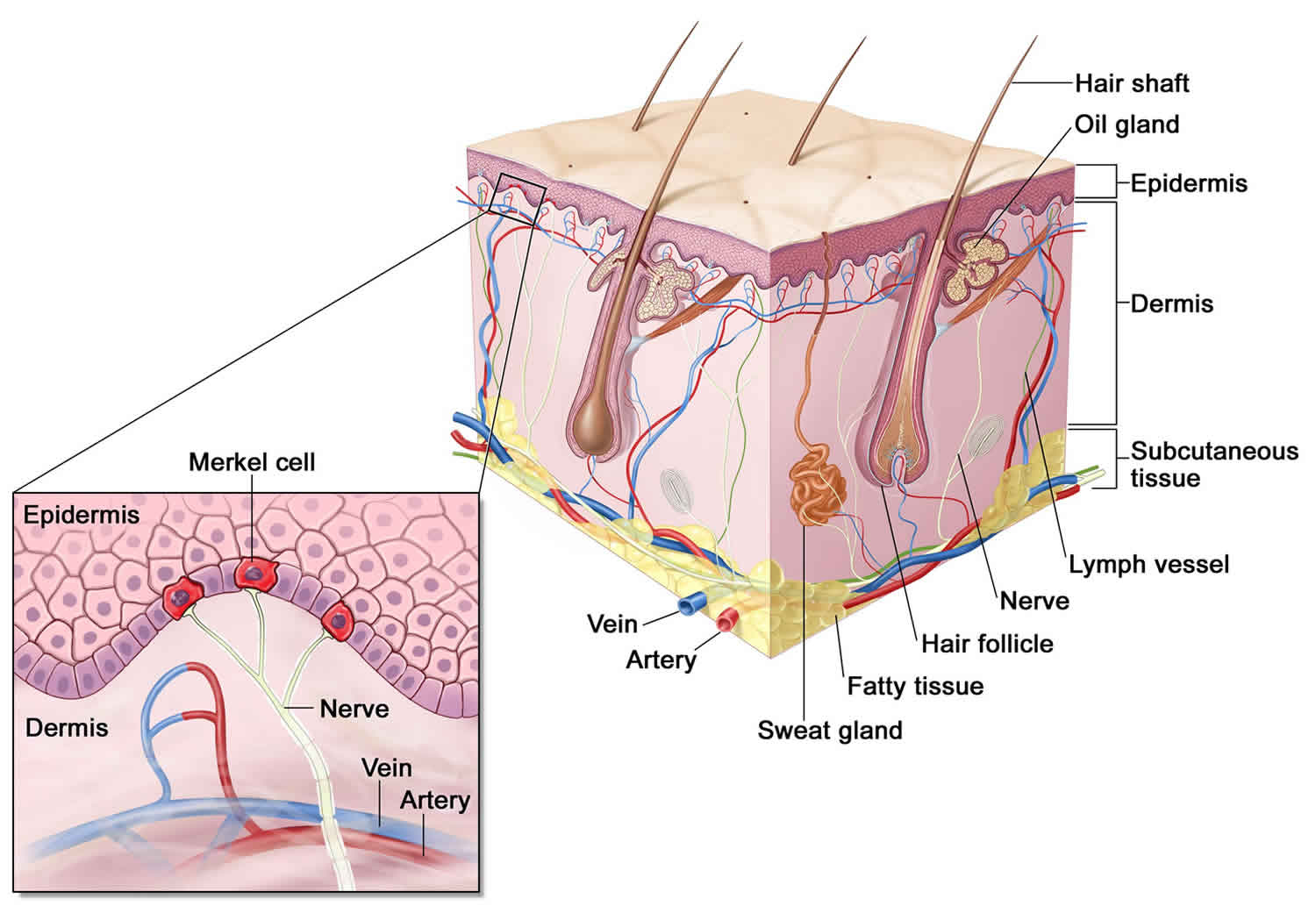

Each adrenal gland is about the size of the top part of the thumb. Each adrenal gland is very vascular and consists of two parts:

- The outer part is the adrenal cortex.

- The central portion is the adrenal medulla.

These regions are not sharply divided, but they are functionally distinct structures that secrete different hormones.

The adrenal cortex and the adrenal medulla have very different functions. One of the main distinctions between them is that the hormones released by the adrenal cortex are necessary for life; those secreted by the adrenal medulla are not.

The adrenal medulla consists of irregularly shaped cells organized in groups around blood vessels. These cells are intimately connected with the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. Adrenal medullary cells are actually modified postganglionic neurons. Preganglionic autonomic nerve fibers control their secretions. The adrenal medulla produces epinephrine and norepinephrine. These hormones are also called adrenaline and noradrenaline.

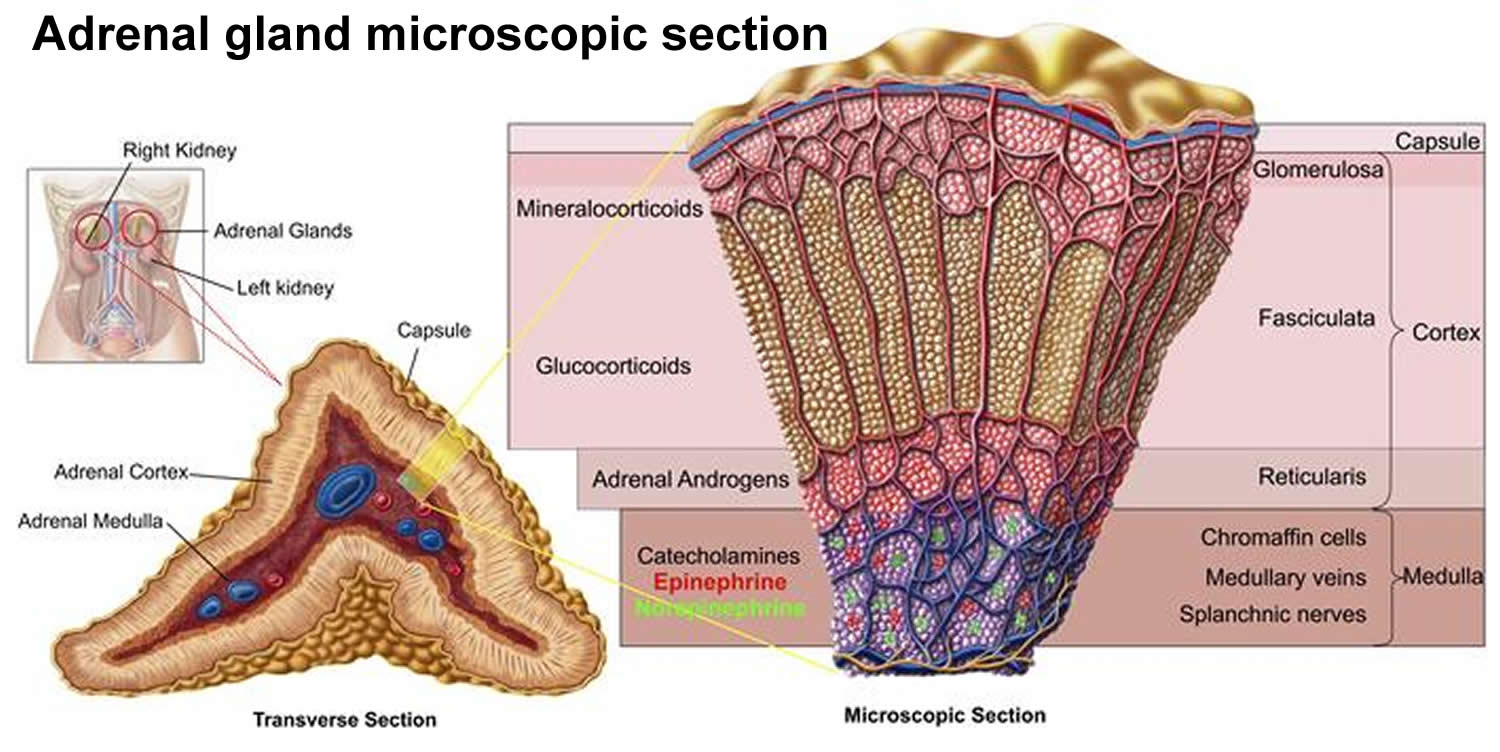

The adrenal cortex, which makes up the bulk of the adrenal gland, is composed of closely packed masses of epithelial cells, organized in layers. These layers form the outer (glomerulosa), middle (fasciculata), and inner (reticularis) zones of the cortex (Figure 3). As in the adrenal medulla, the cells of the adrenal cortex are well supplied with blood vessels. The adrenal cortex produces steroid hormones such as cortisol, aldosterone, and hormones that can be changed into testosterone.

Figure 2. Adrenal gland microscopic section

Adrenal Cortex Hormones

The adrenal cortex produces two main groups of corticosteroid hormones—glucocorticoids and mineralcorticoids. The release of glucocorticoids is triggered by the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Mineralcorticoids are mediated by signals triggered by the kidney.

The principle mineralcorticoid is aldosterone, which maintains the right balance of salt and water while helping control blood pressure. Aldosterone is a hormone produced by the adrenal glands and helps to control the amount of fluid in the body by affecting how much salt and water the kidney retains or excretes. The adrenal glands produce aldosterone in response to another hormone called renin. Renin is produced by specialised cells in the kidney that detect when the body lacks salt; renin released by the kidney signals the adrenal glands to release aldosterone. The kidney detects an increase in aldosterone in the bloodstream and responds by retaining extra salt rather than excreting it in the urine. As the body regains the salt it needs, the level of renin in the bloodstream drops and therefore the amount of aldosterone in the blood also falls, meaning more water is excreted in the urine. This is an example of a feedback system.

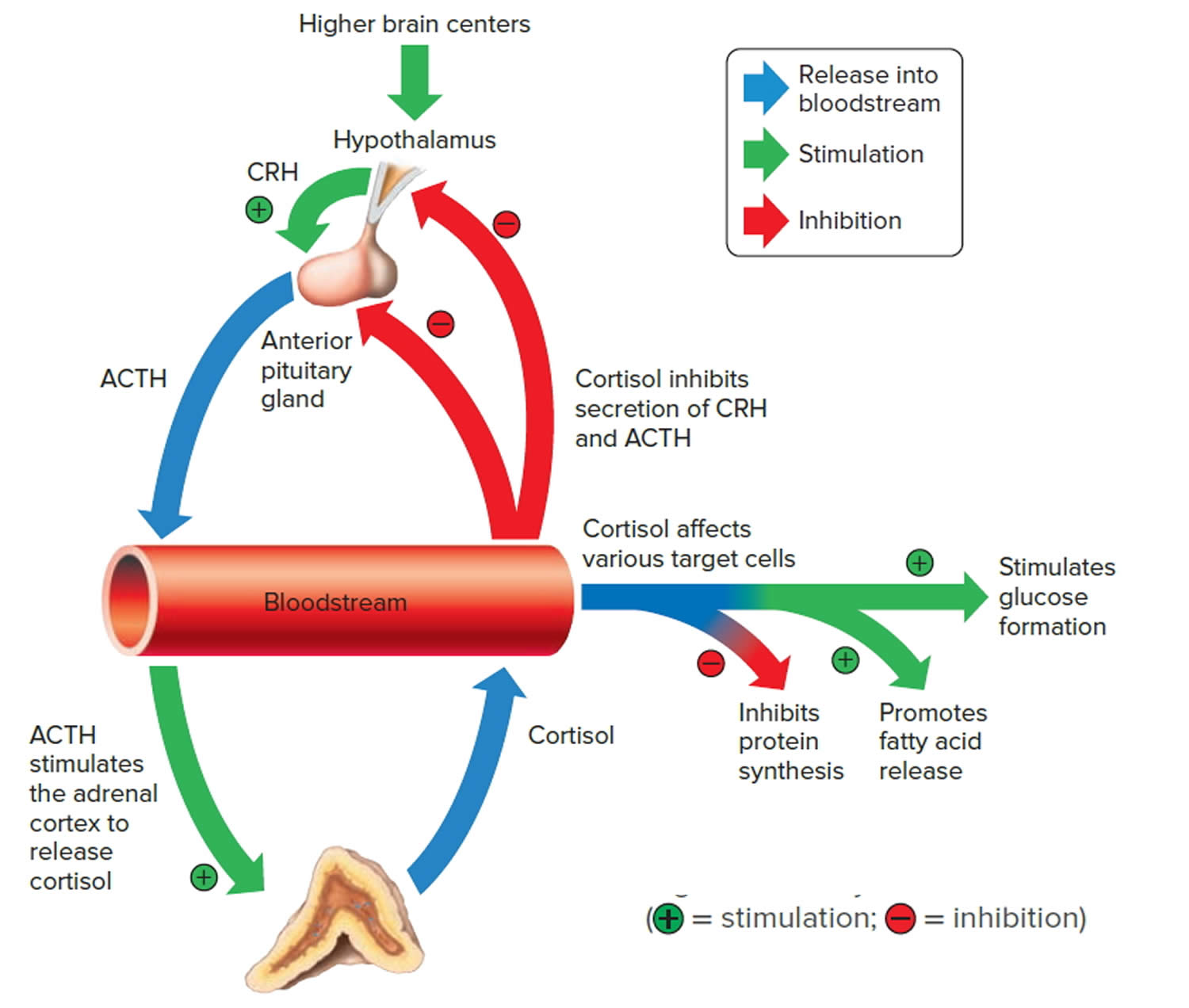

When the hypothalamus produces corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH), it stimulates the pituitary gland to release adrenal corticotrophic hormone (ACTH). These hormones, in turn, alert the adrenal glands to produce corticosteroid hormones.

Glucocorticoids released by the adrenal cortex include:

- 1) Cortisol: Also known as hydrocortisone, it regulates how the body converts fats, proteins, and carbohydrates to energy. It also helps regulate blood pressure and cardiovascular function.

- 2) Corticosterone: This hormone works with hydrocortisone to regulate immune response and suppress inflammatory reactions.

There is a third class of hormone released by the adrenal cortex, known as sex steroids or adrenal sex hormones. The adrenal cortex releases small amounts of male and female sex hormones. These hormones are male types (adrenal androgens), but some are converted to female hormones (estrogens) in the skin, liver, and adipose tissue. The amounts of adrenal sex hormones are very small compared to the supply of sex hormones from the gonads, but they may contribute to

early development of reproductive organs. However, their impact is usually overshadowed by the greater amounts of hormones (such as estrogen and testosterone) released by the ovaries or testes. Cells in the inner zone of the adrenal cortex produce sex hormones.

The more important actions of cortisol include:

- Inhibition of protein synthesis in tissues, increasing the blood concentration of amino acids.

- Promotion of fatty acid release from adipose tissue, increasing the utilization of fatty acids and decreasing the use of glucose as energy sources.

- Stimulation of liver cells to synthesize glucose from noncarbohydrates, such as circulating amino acids and glycerol, increasing the blood glucose concentration.

These actions of cortisol help keep blood glucose concentration within the normal range between meals. This control is important, because a few hours without food can exhaust the supply of liver glycogen, a major source of glucose.

Negative feedback controls cortisol release (see Figure 4). This is much like control of thyroid hormones, involving the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary gland, and adrenal cortex. The hypothalamus secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) into the pituitary gland portal veins, which carry CRH to the anterior pituitary, stimulating it to secrete adrenal corticotrophic hormone (ACTH). In turn, ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex to release cortisol. Cortisol inhibits the release of CRH and ACTH, and as concentrations of these fall, cortisol production drops.

The set point of the feedback mechanism controlling cortisol secretion may change to meet the demands of changing conditions. For example, under stress—as from injury, disease, or emotional upset—information concerning the stressful condition reaches the brain. In response, brain centers signal the hypothalamus to release more corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), elevating the blood cortisol concentration until the stress subsides.

Figure 3. Negative feedback regulates cortisol secretion

Adrenal Medulla Hormones

Unlike the adrenal cortex, the adrenal medulla does not perform any vital functions. That is, you don’t need it to live 45. But that hardly means the adrenal medulla is useless. The hormones of the adrenal medulla are released after the sympathetic nervous system is stimulated, which occurs when you’re stressed. As such, the adrenal medulla helps you deal with physical and emotional stress.

You may be familiar with the fight-or-flight response—a process initiated by the sympathetic nervous system when your body encounters a threatening (stressful) situation. The hormones of the adrenal medulla contribute to this response.

Hormones secreted by the adrenal medulla are:

- Epinephrine: Most people know epinephrine by its other name—adrenaline. This hormone rapidly responds to stress by increasing your heart rate and rushing blood to the muscles and brain. It also spikes your blood sugar level by helping convert glycogen to glucose in the liver. (Glycogen is the liver’s storage form of glucose.)

- Norepinephrine: Also known as noradrenaline, this hormone works with epinephrine in responding to stress. However, it can cause vasoconstriction (the narrowing of blood vessels). This results in high blood pressure.

These adrenal medullary hormones have similar molecular structures and physiological functions. In fact, adrenaline (epinephrine), which makes up 80 percent

of the adrenal medullary secretion, is synthesized from noradrenaline (norepinephrine).

The effects of the adrenal medullary hormones resemble those of sympathetic neurons stimulating their effectors. The hormonal effects, however, last up to ten times longer than nervous stimulation because hormones are broken down more slowly than are neurotransmitters. Adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) increase heart rate, the force of cardiac muscle contraction, and blood glucose level. They also dilate airways, which makes breathing easier, elevate blood pressure, and decrease digestive activity.

Impulses arriving on sympathetic preganglionic nerve fibers stimulate the adrenal medulla to release its hormones at the same time that sympathetic impulses are stimulating other effectors. These sympathetic impulses originate in the hypothalamus in response to stress. In this way, adrenal medullary secretions function with the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system in preparing the body for energy-expending action, also called “fight-or-flight responses.”

Adrenal cortical carcinoma causes

The cause of most adrenal cortical carcinomas is currently unknown. However, scientists have found few risk factors that make a person more likely to develop adrenal cancer. Even if a patient does have one or more risk factors for adrenal cancer, it is impossible to know for sure how much that risk factor contributed to causing the cancer. But having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that you will get the disease. Many people with risk factors never develop adrenal cancer, while others with this disease may have few or no known risk factors. Risk factors such as being overweight, smoking, living a sedentary lifestyle, and being exposed to cancer-causing substances in the environment can affect a person’s risk of many types of cancer. Although none of these factors has been found to definitely influence a person’s risk of developing adrenal cancer, smoking has been suggested as a risk factor by some researchers.

The majority of adrenal cortex cancers are not inherited (sporadic), but some (up to 15%) are caused by a genetic defect. This is more common in adrenal cancers in children 46.

Li-Fraumeni syndrome

Li-Fraumeni syndrome is a rare condition that is most often caused by a defect in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene. People with Li-Fraumeni syndrome have a high risk of several types of cancer, including include breast cancer, bone cancer, brain cancer, and adrenal cortex cancer. Li-Fraumeni syndrome causes a small portion of adrenal cancer in adults (about 1 of every 20), but it’s often the cause of adrenal cancer in children. In fact, about 8 of every 10 cases of adrenal cancer in children are caused by Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Many other adrenal cancers have also been found to have TP53 gene changes that were acquired after birth (not inherited).

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

People with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome have large tongues, are large themselves, and have an increased risk for developing cancers of the kidney, liver and adrenal cortex.

Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN1)

People with MEN1 have a very high risk of developing tumors of 3 glands: the pituitary, parathyroid, and pancreas. About one-third to one-half of people with this condition also develop adrenal adenomas (benign tumors) or enlarged adrenal glands. These usually do not cause any symptoms. This syndrome is caused by defects in a gene called MEN1. People who have a family history of MEN1 or pituitary, parathyroid, pancreas, or adrenal cancers should ask their doctor if they might benefit from genetic counseling.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

People with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) develop hundreds of polyps in the large intestine. These polyps will lead to colon cancer if the colon is not removed. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) also increases the risk of other cancers, and may increase the risk for adrenal cancer. Still, most adrenal tumors in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis are benign adenomas. This syndrome is caused by defects in a gene called APC.

Lynch syndrome or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)

Lynch syndrome also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is an inherited genetic disorder that increases the risk of colorectal cancer, stomach cancer, and some other cancers, including adrenal cortex cancer. In most cases, this disorder is caused by a defect in either the MLH1 or MSH2 gene, but other genes can cause Lynch syndrome, including MLH3, MSH6, TGFBR2, PMS1, and PMS2.

Adrenal cortical carcinoma prevention

Since there are no known preventable risk factors for this cancer, it is not possible to prevent adrenal cortical carcinoma at this time. Tobacco use has been suggested as a risk factor for adrenal cancer by some researchers, so not smoking might help reduce your risk.

Adrenal cortical carcinoma symptoms

In about half of people with adrenal cancer, symptoms are caused by the hormones made by the tumor. In the other half, symptoms occur because the tumor has grown so large that it presses on nearby organs.

As an adrenal cancer grows, it presses on nearby organs and tissues. This may cause pain near the tumor, a feeling of fullness in the abdomen, pain in your abdomen or back, or trouble eating because of a feeling of filling up easily.

Adrenocortical carcinoma symptoms may also include high blood pressure (hypertension), weight gain, frequent urination and possibly deepening of your voice. These symptoms are due to adrenocortical carcinoma causing excess secretion of hormones from the adrenal glands.

Symptoms of increased cortisol or other adrenal gland hormones may include:

- Fatty, rounded hump high on the back just below the neck (buffalo hump)

- Flushed, rounded face with pudgy cheeks (moon face)

- Obesity

- Stunted growth (short stature)

- Virilization — the appearance of male characteristics, including increased body hair (especially on the face), pubic hair, acne, deepening of the voice, and enlarged clitoris (females). Virilization is caused by an excess of androgen (male-type hormone) secretion is seen, alone or in combination with hypercortisolism, in more than 80% of patients 12, 47.

Symptoms of increased aldosterone are the same as symptoms of low potassium, and include:

- Muscle cramps

- Weakness

- Pain in your abdomen

A functioning adrenal cortical carcinoma makes too much of one of the following hormones, as well as other hormones 37:

- Cortisol. Too much cortisol may cause problem known as Cushing syndrome:

- Weight gain in the face, neck, and trunk of the body and thin arms and legs.

- Growth of fine hair on the face, upper back, or arms.

- A round, red, full face (moon face).

- Fat deposits behind the neck and shoulders (fatty hump or buffalo hump)

- A deepening of the voice and swelling of the sex organs or breasts in both males and females.

- Purple stretch marks on your abdomen

- Muscle weakness and loss of muscle mass in your legs.

- Weakened bones (osteoporosis), which can lead to fractures

- High blood sugar levels, often leading to diabetes

- High blood pressure

- Easy bruising

- Depression and/or moodiness

- Menstrual irregularities in women.

- Aldosterone. Too much aldosterone may cause:

- High blood pressure.

- Low blood potassium levels

- Muscle weakness or cramps.

- Frequent urination.

- Feeling thirsty.

- Testosterone. Men who make too much testosterone do not usually have signs or symptoms. However, too much testosterone in women may cause:

- Growth of fine hair on the face, upper back, or arms.

- Acne.

- Balding.

- A deepening of the voice.

- No menstrual periods.

- Estrogen (female-type hormone).

- Too much estrogen in women may cause:

- Irregular menstrual periods in women who have not gone through menopause.

- Vaginal bleeding in women who have gone through menopause.

- Weight gain.

- Too much estrogen in men may cause:

- Growth of breast tissue.

- Lower sex drive.

- Impotence.

- Too much estrogen in women may cause:

Adrenocortical carcinoma can be classified into functioning and nonfunctioning tumors by clinical and biochemical assessment. Approximately 60% of adrenocortical carcinomas produce hormones 36. Nonfunctional adrenocortical carcinomas are rare (<10%) and tend to occur in older children 5.

These signs and symptoms may be caused by adrenocortical carcinoma or by other conditions. Check with your doctor if you have any of these problems.

Adrenal cortical carcinoma diagnosis

To diagnose adrenal cortical carcinoma your doctor will take your medical history, perform a physical exam and ask about your symptoms.

Medical history

- Your doctor will want to know if anyone in your family has had adrenal cancer or any other type of cancer.

- Your doctor might also ask about your menstrual or sexual function and about any other symptoms you may be having.

Physical examination

A physical exam will give other information about possible signs of adrenal cancer or other health problems.

- Your doctor will thoroughly examine your abdomen for evidence of a tumor (or mass).

- Your blood and urine will likely be tested to look for high levels of the hormones made by some adrenal tumors.

- If an adrenal tumor is suspected, imaging tests will be done to look for it. These tests can also help see if it has spread.

If a mass is seen on an imaging test and it is likely to be an adrenal cancer, doctors will recommend surgery to remove the cancer. Generally, doctors do not recommend a biopsy (removing a sample of the tumor to look at under the microscope to see if it is cancer) before surgery to remove the tumor. This is because doing a biopsy can increase the risk that an adrenal cancer will spread outside of the adrenal gland.

Blood and urine tests

Blood and urine tests to measure levels of adrenal hormones are important in deciding whether a patient with signs and symptoms of adrenal cancer has the disease. For urine tests, you may be asked to collect all of your urine for 24 hours. Blood and urine tests are as important as imaging tests in diagnosing adrenal cancer. Doctors might choose which tests to do based on the patient’s symptoms. But often doctors will check hormone levels even when symptoms of high hormone levels are not present. This is because symptoms of abnormal hormone levels can be very subtle, and blood tests might be able to detect changes in hormone levels even before symptoms occur.

Blood and urine tests will be done to check hormone levels:

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) level will be low.

- Aldosterone level will be high. The level of aldosterone will be measured and will be high if the tumor is making aldosterone. High aldosterone can also lead to low blood levels of potassium and renin (a hormone made by the kidneys) .

- Cortisol level will be high. The levels of cortisol are measured in the blood and in the urine. If an adrenal tumor is making cortisol, these levels will be abnormally high. These tests may be done after giving the patient a dose of dexamethasone. Dexamethasone is a drug that acts like cortisol. If given to someone who does not have an adrenal tumor, it will lower levels of cortisol and similar hormones. In someone with an adrenal cortex tumor, these hormone levels will remain high after they receive dexamethasone. Blood levels of another hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) will also be measured to help distinguish adrenal tumors from other diseases that can cause high cortisol levels.

- Blood chemistry study. A procedure in which a blood sample is checked to measure the amounts of certain substances, such as potassium or sodium, released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body.

- Potassium level will be low.

- Male or female hormones may be abnormally high. Patients with androgen-producing tumors will have high levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) or testosterone. Patients with estrogen-producing tumors will have high levels of estrogen in their blood.

- Twenty-four-hour urine test. A test in which urine is collected for 24 hours to measure the amounts of cortisol or 17-ketosteroids. A higher than normal amount of these in the urine may be a sign of disease in the adrenal cortex.

- Low-dose dexamethasone suppression test. A test in which one or more small doses of dexamethasone are given. The level of cortisol is checked from a sample of blood or from urine that is collected for three days. This test is done to check if the adrenal gland is making too much cortisol.

- High-dose dexamethasone suppression test. A test in which one or more high doses of dexamethasone are given. The level of cortisol is checked from a sample of blood or from urine that is collected for three days. This test is done to check if the adrenal gland is making too much cortisol or if the pituitary gland is telling the adrenal glands to make too much cortisol.

Imaging studies

Imaging tests may include:

- Chest x-ray. A chest x-ray can show if the cancer has spread to the lungs. It may also be useful to determine if there are any serious lung or heart diseases.

- Ultrasound. Ultrasound tests use sound waves to make pictures of parts of the body. A device called a transducer makes the sound waves, which are reflected off of tissues and organs in your body. The pattern of sound wave echoes is detected by the transducer and analyzed by a computer to create an image of these tissues and organs. This test can show if there is a tumor in the adrenal gland. It can also show tumors in the liver if the cancer has spread there. In general, ultrasound is not used to look for adrenal tumors unless a CT scan can’t be done for some reason.

- CT scan (CAT scan). A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside your body, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into your vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography. CT scans show the adrenal glands fairly clearly and often can confirm the location of the cancer. CT scans can also show lymph nodes and distant organs where metastatic cancer might be present. The CT scan can help determine if surgery is a good treatment option.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI). An MRI of the abdomen is done to diagnose adrenocortical carcinoma. MRI may sometimes provide more information than CT scans because it can better distinguish adrenal cancers from benign tumors. MRI scans are particularly helpful in examining the brain and spinal cord. In people with suspected adrenal tumors, an MRI of the brain may be done to examine the pituitary gland. Tumors of the pituitary gland, which lies underneath the front of the brain, can cause symptoms and signs similar to adrenal tumor.

- PET scan (positron emission tomography scan). A procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into your vein. The PET scanner rotates around your body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in your body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do. PET scans can be helpful in deciding if an adrenal tumor is likely to be benign or malignant (cancer), and if it may have spread. Some machines do both a PET and CT scan at the same time (PET/CT scan). This lets the doctor see areas that “light up” on the PET scan in more detail.

- Adrenal angiography. A procedure to look at the arteries and the flow of blood near the adrenal glands. A contrast dye is injected into the adrenal arteries. As the dye moves through the arteries, a series of x-rays are taken to see if any arteries are blocked.

- Adrenal venography. A procedure to look at the adrenal veins and the flow of blood near the adrenal glands. A contrast dye is injected into an adrenal vein. As the contrast dye moves through the veins, a series of x-rays are taken to see if any veins are blocked. A catheter (very thin tube) may be inserted into the vein to take a blood sample, which is checked for abnormal hormone levels.

- MIBG scan. A very small amount of radioactive material called MIBG is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. Adrenal gland cells take up the radioactive material and are detected by a device that measures radiation. This scan is done to tell the difference between adrenocortical carcinoma and pheochromocytoma.

Laparoscopy

A laparoscope, a thin, flexible tube with a tiny video camera on the end, is inserted through a small surgical opening in the patient’s side to allow the surgeon to see where the cancer is growing. A laparoscope can be used to help spot distant spread as well as enlarged lymph nodes (which might contain cancer). Sometimes it is combined with ultrasound to give a better picture of the cancer. Laparoscopy may be done to help predict whether it will be possible to completely remove the cancer by surgery. In addition to viewing adrenal tumors through the laparoscope, surgeons can sometimes remove small benign adrenal tumors through this instrument.

Biopsy

The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer. The sample may be taken using a thin needle, called a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy or a wider needle, called a core biopsy.

Since adrenal adenomas (benign tumors) and cancers can look alike under the microscope, a biopsy may not be able to tell whether or not an adrenal tumor is cancerous 48. A needle biopsy of an adrenal cancer also can actually spread tumor cells. For these reasons, a biopsy is generally not done before surgery if an adrenal tumor’s size and certain features seen on imaging tests suggest it is most likely cancer 48. Blood tests of hormone levels and imaging tests are more useful than biopsies in diagnosing adrenal cancer 48.

If the cancer appears to have metastasized (spread) to another part of the body such as the liver, then a needle biopsy of the metastasis may be done. If a patient is known to have an adrenal tumor and a liver biopsy shows adrenal cells are present in the liver, then the tumor is cancer.

In general, a biopsy is only done in a patient with adrenal cancer when there are tumors outside the adrenals and the doctor needs to know if these tumors are from the adrenal cancer or are caused by some other cancer or disease. Tumors in the adrenal glands are sometimes biopsied when the patient is known to have a different type of cancer (like lung cancer), and knowing if it has spread to the adrenal glands would alter treatment.

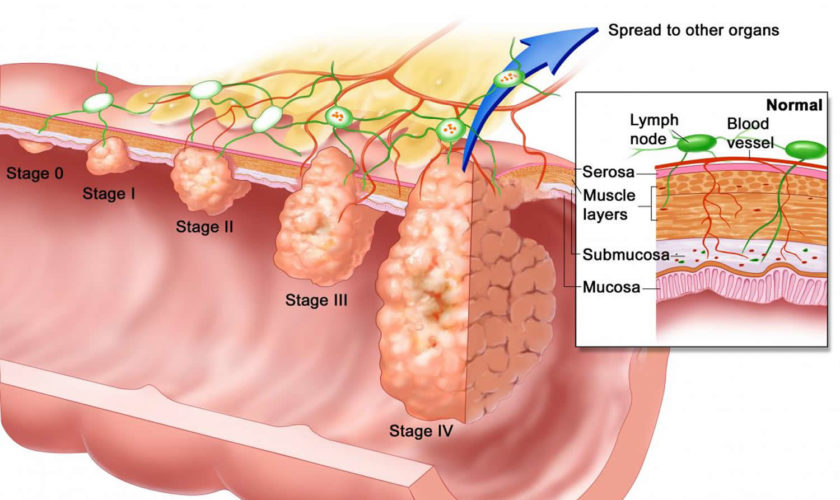

Adrenal cortical carcinoma staging

After your adrenocortical carcinoma has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the adrenal gland or to other parts of your body. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

In adults with adrenal cortical carcinoma, both the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor, Node, and Metastases (TNM) staging system and the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENSAT) staging system is used 49.

Both the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENSAT) are based on the same TNM categories, which are based on 3 key pieces of information for adults with adrenal cortical carcinoma:

- The extent (size) of the tumor (T): T describes the size of the main (primary) tumor and whether it has grown into nearby areas. How large is the cancer? Has it grown into nearby areas?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes? If so, how many? Lymph nodes are small bean-sized collections of immune system cells, to which cancers often spread first.

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant organs such as your liver, bone, lung, or other areas?

The adrenal cancer stages range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a general rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage 4( IV), means a more advanced cancer.

The following American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENSAT) Tumor, Node, and Metastases (TNM) stages are used for adrenocortical carcinoma in adults:

- Stage 1. In stage 1, the tumor is 5 centimeters or smaller and is found in the adrenal gland only.

- Stage 2. In stage 2, the tumor is larger than 5 centimeters and is found in the adrenal gland only.

- Stage 3. In stage 3, the tumor is any size and has spread:

- to nearby lymph nodes; or

- to nearby tissues or organs (kidney, diaphragm, pancreas, spleen, or liver) or to large blood vessels (renal vein or vena cava) and may have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- Stage 4. In stage 4, the tumor is any size, may have spread to nearby lymph nodes, and has spread to other parts of the body, such as the lung, bone, or peritoneum.

Table 1. the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENSAT) TNM staging system for adrenal cancer in adults

| ENSAT stage | AJCC Stage | Stage grouping | Stage description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | T1 N0 M0 | The tumor is 5 cm (about 2 inches) or less in size and it has not grown into tissues outside the adrenal gland (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). |

| 2 | 2 | T2 N0 M0 | The tumor is greater than 5 cm (2 inches) in size and it has not grown into tissues outside the adrenal gland (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). |

| 3 | 3 | T1 N1 M0 | The tumor is 5 cm (about 2 inches) or less in size and it has not grown into tissues outside the adrenal gland (T1). The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1) but not to distant sites (M0). |

| OR | |||

| T2 N1 M0 | The tumor is greater than 5 cm (2 inches) in size and it has not grown into tissues outside the adrenal gland (T2). The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1) but not to distant sites (M0). | ||

| OR | |||

| T3 Any N M0 | The tumor is growing in the fat that surrounds the adrenal gland. The tumor can be any size (T3). It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N0). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). | ||

| OR | |||

| T4 Any N M0 | The tumor is growing into nearby organs, such as the kidney, pancreas, spleen, and liver or large blood vessels (renal vein or vena cava). The tumor can be any size (T4). It may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has not spread to distant organs (M0). | ||

| 4 | 4 | Any T Any N M1 | The cancer has spread to distant sites like the liver or lungs (M1). It can be any size (Any T) and may or may not have spread to nearby tissues (Any T) or lymph nodes (Any N). |

Footnotes: The following additional categories are not listed on the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information

In children with adrenal cortical carcinoma the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) based on clinical data from the International Pediatric Adrenocortical Tumor Registry is used for staging purposes 51. The Children’s Oncology Group for adrenal cortical carcinoma staging are divided into four groups 52:

- Stage 1. Completely resected tumors <100 g and 200 cm³ with normal postoperative hormone levels. Stage 1 disease appears to be associated with a better prognosis 53

- Stage 2. Completely resected tumors ≥100 g or ≥200 cm³ with normal postoperative hormone levels,

- Stage 3. Residual disease or inoperable tumors, and

- Stage 4. Distant metastatic disease.

Adrenal cancer staging can be complex. If you have any questions about your stage, please ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Overall, adverse prognostic factors for adrenocortical carcinoma include the following 54:

- Large tumor size. Tumor weight heavier than 200 g and tumor volume greater than 200 mL have been associated with a worse outcome 55, 56. Patients with small tumors have an excellent outcome when treated with surgery alone, regardless of histological features 57, 53, 8

- Metastatic disease 55, 56, 57, 53, 8

- Age. Age older than 4 or 5 years 55, 56, 53, 8, 5

- Microscopic tumor necrosis 53

- Para-aortic lymph node involvement 53

- Incomplete resection or spillage during surgery 55, 56, 8

- Low HLA class 2 antigen expression. A low expression of the HLA class 2 antigens HLA-DRA, HLA-DPA1, and HLA-DPB1 has been associated with older age, larger tumor size, presence of metastatic disease, and worse outcome 58. In children, increased expression of MHC class 2 genes, especially HLA-DPA1, is associated with a better prognosis 59.

- Higher Ki-67 labeling index. A retrospective analysis of patients with adrenocortical carcinoma reported that higher Ki-67 labeling index correlated with worse overall survival and disease-free survival 60

Adrenal cortical carcinoma treatment

The main treatment for adrenal cortical carcinoma is surgery to remove the tumor. For advanced adrenal cortical carcinoma may also be treated with chemotherapy mitotane and cisplatin-based regimens, usually incorporating doxorubicin and etoposide 12, 61, 7, 15, 62. You may also get medicines (i.e., ketoconazole and metyrapone) to reduce production of cortisol, which causes many of your symptoms.

The use of radiation therapy in pediatric patients with adrenocortical carcinomas has not been consistently investigated. Adrenocortical carcinomas are generally considered to be radioresistant. Furthermore, because many children with adrenocortical carcinomas carry germline TP53 mutations that predispose them to cancer, radiation may increase the incidence of secondary tumors. One study reported that three of five long-term survivors of pediatric adrenocortical carcinomas died of secondary sarcomas that arose within the radiation field 12, 63.

Treatment options for childhood adrenocortical carcinomas include the following 54:

- Surgery. An aggressive surgical approach toward the primary tumor and all metastatic sites is recommended when feasible 64, 65. Because of tumor friability, rupture of the capsule with resultant tumor spillage is frequent (approximately 20% of initial resections and 43% of resections after recurrence) 5. When the diagnosis of adrenocortical carcinoma is suspected, laparotomy and a curative procedure are recommended rather than fine-needle aspiration to avoid the risk of tumor rupture 65, 66.. Laparoscopic resection is associated with a high risk of rupture and peritoneal carcinomatosis; thus, open adrenalectomy remains the standard of care 67.

- Mitotane and cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens. In adults, mitotane is commonly used as a single agent in the adjuvant setting after complete resection 61. Little information is available about the use of mitotane in children, although response rates appear to be similar to those seen in adults 61, 68.

- A retrospective analysis in Italy and Germany identified 177 adult patients with completely resected adrenocortical carcinoma. Recurrence-free survival was significantly prolonged by the use of adjuvant mitotane. Benefit was present with 1 to 3 g per day of mitotane and was associated with fewer toxic side effects than doses of 3 to 5 g per day 69

- In a review of 11 children with advanced adrenocortical tumors treated with mitotane and a cisplatin-based chemotherapeutic regimen, measurable responses were seen in seven patients. The mitotane daily dose required for therapeutic levels was approximately 4 g/m2, and therapeutic levels were achieved after 4 to 6 months of therapy 61

- In the GPOH-MET 97 trial, mitotane levels greater than 14 mg/L correlated with better survival 12, 7

- The Children’s Oncology Group conducted a prospective, single-arm, risk-stratified, interventional study between 2006 and 2013 70. Stage 1 patients had small tumors limited to the adrenal gland and were treated with adrenalectomy alone. Stage 2 patients had tumors larger than 200 mL or heavier than 100 g and were treated with adrenalectomy and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (retroperitoneal lymph node dissection). Stage 3 patients had incompletely resected primary tumors. Stage 4 patients had distant metastatic disease. Patients with stage 3 and stage 4 disease were treated with surgery of the primary tumor, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, cisplatin, etoposide, doxorubicin, and mitotane.

- The 5-year event-free survival rate estimates were 86.2% for stage 1 (24 patients), 53.3% for stage 2 (15 patients), 81% for stage 3 (24 patients), and 7.1% for stage 4 (14 patients).

- On multivariable analysis, only stage and age were significantly associated with outcome.

- The authors reported that the combination of mitotane and chemotherapy resulted in significant toxicity. One-third of patients with advanced disease could not complete the scheduled treatment.

- The stated goal of the study was to determine if retroperitoneal lymph node dissection would improve outcome for stage 2 patients 71. The operative notes to assess the adequacy of the retroperitoneal lymph node dissection were available for 11 of 15 patients. The median number of lymph nodes resected was 4 (range, 1–30). In a multivariable analysis performed in a cohort of 283 adult patients with adrenocortical carcinoma, patients who underwent retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (defined as >5 nodes resected) had a significantly reduced recurrence risk and disease-related death rate than patients who did not undergo nodal dissection 71. The authors speculate that the retroperitoneal lymph node dissections performed in this study may not have been as thorough as the procedures carried out in the adult series, which could confound conclusions about the potential value of retroperitoneal lymph node dissection.

- Treatment options for relapsed childhood adrenocortical tumors include the checkpoint inhibitors. In a phase 1/2 trial of pediatric patients with advanced or relapsed solid tumors who were treated with pembrolizumab, two of four patients with adrenocortical carcinoma achieved partial responses 72.

Surgery

The main treatment for adrenal cancer is removal of the adrenal gland, an operation called an adrenalectomy. The surgeon will try to remove as much of the cancer as possible, including any areas of cancer spread. If nearby lymph nodes are enlarged, they also will need to be removed and checked for cancer spread.

One way to remove the adrenal gland is through an incision in the back, just below the ribs. This works well for small tumors, but it can be hard to see larger tumors well.

More often, the surgeon makes the incision through the front of the abdomen. This lets the surgeon see the tumor more clearly and makes it easier to see if it has spread. It also gives the surgeon room to remove a large cancer that has grown into tissues and organs near the adrenal gland. For example, if the cancer has grown into the kidney, all or part of the kidney must also be removed. If it has grown into the muscle and fat around the adrenal gland, these tissues will need to be removed as well.

Sometimes, the cancer can grow into the inferior vena cava, the large vein that carries blood from the lower body to the heart. If this is the case, it requires a very extensive operation to remove the tumor completely and preserve the vein. To remove the tumor from the vein, the surgeon may need to bypass the body’s circulation by putting the patient on a heart-lung bypass pump like that used in heart surgery. If the cancer has grown into the liver, the part of the liver containing the cancer might need to be removed, too.

It is also possible to remove some small adrenal tumors through a thin hollow, lighted tube (with a tiny video camera on the end) called a laparoscope. Instead of a large incision in the skin to remove the tumor, several small ones are made. The surgeon inserts the laparoscope through one of them to look inside the belly. Then, other instruments inserted through this tube or through other small incisions are used to remove the adrenal gland. The main advantage of this method is that because the incisions are smaller, patients recover from surgery more quickly.

Although laparoscopic surgery is used to treat adrenal adenomas (benign tumors), it often is not an option for treating larger adrenal cancers. This is because it’s important to remove the tumor in one piece whenever possible. To remove a large tumor with a laparoscope, the surgeon might have to break it up into small pieces first. Doing that raises the risk of the cancer spreading. Adrenal cancers that have grown into nearby tissues or lymph nodes can also be hard to remove completely using laparoscopy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (chemo) is the use of certain types of drugs to treat cancer. Typically, the drugs are given into a vein or by mouth (in pill form). These drugs enter the bloodstream and reach throughout the body, making this treatment useful for cancer that has spread (metastasized) to organs beyond the adrenal gland. Chemo does not work very well for adrenal cancer, so it is most often used for adrenal cancer that has become too widespread to be removed with surgery (although it is very unlikely to cure the cancer).

Mitotane

Mitotane is the drug most often used for people with adrenal cancer. It blocks hormone production by the adrenal gland and also destroys both adrenal cancer cells and healthy adrenal tissue. This drug can also suppress the usual adrenal steroid hormone production from your other, normal adrenal gland. This can lead to low levels of cortisol and other hormones, which can make you feel weak and sick. If this occurs, you’ll need to take steroid hormone pills to bring your hormone levels up to normal. Mitotane can also alter levels of other hormones, such as thyroid hormone or testosterone. If that occurs, you’d need drugs to replace these hormones as well.

Sometimes mitotane is given for a period of time after surgery has removed all the (visible) cancer. This is called adjuvant therapy and is meant to kill any cells that were left behind but were too small to see. Giving the drug this way may prevent or delay the cancer’s return. .

If the cancer has not been completely removed by surgery or has come back, mitotane will shrink the cancer in some patients. On average, the response lasts about a year, but it can be longer for some patients.

Mitotane is particularly helpful for people with adrenal cancers who have problems caused by excessive hormone production. Even when it doesn’t shrink the tumor, mitotane can reduce abnormal hormone production and relieve symptoms. Most patients with excess hormone production are helped by mitotane.

This drug can cause major side effects. The most common are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rashes, confusion, and sleepiness. Sometimes lower doses of the drug can still be effective and cause fewer side effects.

This drug is taken as a pill 3 to 4 times a day. Like other types of chemo, treatment with mitotane needs to be supervised closely by a doctor.

Other chemo drugs used for adrenal cancer

Drugs are sometimes combined with mitotane to treat advanced adrenal cancer. The drugs used most often are:

- The combination of cisplatin, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and etoposide (VP-16) plus mitotane

- Streptozocin plus mitotane

Chemo drugs used less often, include:

- Paclitaxel (Taxol)

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)

- Vincristine (Oncovin)

These drugs may be given in different combinations and are often given with mitotane.

Chemo drug side effects

Chemotherapy drugs kill cancer cells but also damage some normal cells, which can cause some side effects. Side effects from chemo depend on the type of drugs, their doses, and how long treatment lasts. Common side effects of chemo include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Loss of hair

- Hand and foot rashes

- Mouth sores

- Diarrhea

- Increased risk of infection (due to a shortage of white blood cells)

- Problems with bleeding or bruising after minor cuts or injuries (due to a shortage of blood platelets)

- Anemia, fatigue, or shortness or breath (due to low red blood cell counts)

Along with the risks above, some chemo drugs can cause other side effects.

Ask your doctor what side effects you can expect based on the specific drugs you will get. Be sure to tell your doctor or nurse if you do have side effects, as there are often ways to help with them. For example, drugs can be given to help prevent or reduce nausea and vomiting.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is not used often as the main initial treatment for adrenal cancer because the cancer cells are not easy to kill with x-rays. Radiation may be used after surgery to help keep the tumor from coming back. This is called adjuvant therapy. Radiation can also be used to treat areas of cancer spread, such as in the bones or brain.

Common side effects of radiation therapy include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea (if an area of the abdomen is treated)

- Skin changes in the area being treated, which can range from redness to blistering and peeling

- Hair loss in the area being treated

- Fatigue

- Low blood counts.

Drugs to block hormones made by adrenal cortical carcinoma

Drugs other than mitotane may be used to block hormones made by adrenal carcinoma or to lower the effects of the hormones. Treatment with some of these drugs may need to be supervised by an endocrinologist (hormone doctor) because they affect several hormone systems and might make it necessary to replace other hormones.

Ketoconazole and metyrapone can reduce adrenal steroid hormone production. This can help relieve symptoms caused by these hormones, but it doesn’t shrink the cancer.

Some drugs block the effects of the hormones made by the tumor. These include:

- Spironolactone (Aldactone), which decreases effects of aldosterone

- Mifepristone (Korlym), which decreases cortisol effects

- Tamoxifen, toremifene (Fareston), and fulvestrant (Faslodex), can block the effects of estrogen. These drugs are more often used to treat breast cancer, but can be useful in some patients (often men) who have adrenal tumors that make estrogen.

Stage 1 adrenocortical carcinoma treatment

Treatment of stage 1 adrenocortical carcinoma may include the following:

- Surgery (adrenalectomy). The entire adrenal gland will be removed. Nearby lymph nodes may also be removed if they are larger than normal.

- A clinical trial of a new treatment.

Since a person has 2 adrenal glands, removal of the diseased one does not generally cause problems for the patient. If nearby lymph nodes are enlarged, they will be removed as well and checked to see if they contain cancer cells. Most surgeons do not remove these lymph nodes if they’re not enlarged.

In many cases, no further treatment is necessary. If the tumor was not removed completely, treatment with radiation and/or mitotane may be given after surgery to help keep the cancer from coming back.

These treatments may also be given if the tumor has a higher chance of coming back later because it was large or appears to be growing quickly (when looked at with a microscope). When treatment is given after surgery has removed all visible cancer, it is called adjuvant therapy. The goal of adjuvant therapy is to kill any cancer cells that may have been left behind but are too small to be seen. Killing these cells lowers the chance of the cancer coming back later.

Stage 2 adrenocortical carcinoma treatment

Treatment of stage 2 adrenocortical carcinoma may include the following:

- Surgery (adrenalectomy). The entire adrenal gland will be removed. Nearby lymph nodes may also be removed if they are larger than normal.

- A clinical trial of a new treatment.

Since a person has 2 adrenal glands, removal of the diseased one does not generally cause problems for the patient. If nearby lymph nodes are enlarged, they will be removed as well and checked to see if they contain cancer cells. Most surgeons do not remove these lymph nodes if they’re not enlarged.

In many cases, no further treatment is necessary. If the tumor was not removed completely, treatment with radiation and/or mitotane may be given after surgery to help keep the cancer from coming back.

These treatments may also be given if the tumor has a higher chance of coming back later because it was large or appears to be growing quickly (when looked at with a microscope). When treatment is given after surgery has removed all visible cancer, it is called adjuvant therapy. The goal of adjuvant therapy is to kill any cancer cells that may have been left behind but are too small to be seen. Killing these cells lowers the chance of the cancer coming back later.

Stage 3 adrenocortical carcinoma treatment

Treatment of stage 3 adrenocortical carcinoma may include the following:

- Surgery (adrenalectomy). The entire adrenal gland will be removed. Nearby lymph nodes may also be removed if they are larger than normal.

- A clinical trial of radiation therapy.

- A clinical trial of a new treatment.

Surgery is the main treatment for stage 3 adrenal cancer. The goal of surgery is to remove all of the cancer. The adrenal gland with the tumor is always removed, and the surgeon might also need to remove some tissue around the adrenal gland, including part (or all) of the nearby kidney and part of the liver. The lymph nodes near the adrenal gland will also be removed. After surgery, adjuvant treatment with radiation and/or mitotane may be given to help keep the cancer from coming back.

Stage 4 adrenocortical carcinoma treatment

Treatment of stage 4 adrenocortical carcinoma may include the following as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life:

- Chemotherapy or combination chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy to bones or other sites where cancer has spread.

- Surgery to remove cancer that has spread to tissues near the adrenal cortex.

- A clinical trial of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy.

If it is possible to remove all of the cancer, then surgery may be done. When the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, it usually cannot be cured with surgery. Some doctors may still recommend surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible. This type of surgery is called debulking. Removing most of the cancer may help reduce symptoms by lowering the production of hormones. Radiation therapy may also be used to treat any areas of cancer that are causing symptoms. For example, radiation can help when cancer that has spread to the bones is causing pain. Mitotane therapy is also an option. Treatment may begin right away, or it may be postponed until the cancer is causing symptoms. Other chemotherapy (chemo) drugs may also be used.

Recurrent adrenocortical carcinoma treatment

Cancer is called recurrent when it comes back after treatment. Recurrence can be local (in or near the same place it started) or distant (in other organs such as the lungs or bones). Local recurrence may be treated with surgery to remove the cancer. This is more likely to be done if all of the cancer can be removed. Distant recurrence is treated like stage IV disease. Debulking (removing as much of the cancer as possible) surgery may be done to relieve symptoms. People with recurrent adrenocortical carcinoma are often treated with mitotane and/or other chemo drugs. They may also receive radiation therapy. If the mitotane doesn’t work or cannot be tolerated, other drugs can be given to lower hormone production.

Treatment of recurrent adrenocortical carcinoma may include the following as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life:

- Surgery.

- Radiation therapy.

- A clinical trial of chemotherapy or immunotherapy.

Most of the time, these treatments provide only temporary help because the tumor will eventually continue to grow. When this happens and these treatments are no longer helping, treatment aimed at providing as good a quality of life as possible may be the best choice. The best medicines to treat pain are morphine and other opioids. Many studies have shown that taking morphine as directed for pain does not mean a person will become addicted.

There are many other ways your doctor can help maintain your quality of life and control your symptoms. This means that you must tell your doctor how you are feeling and what symptoms you are having. Many patients don’t like to disappoint their doctors by telling them they are not feeling well. This does no one any good.

Follow-up care

Follow-up care will be very important after treatment for adrenal cancer. One reason for this is that the cancer can come back (recur), even after treatment for early-stage disease. Your doctor will want to see you frequently in the first months and years after treatment, but this might become less often as time goes on. This is a good time for you to talk to your cancer care team about any changes or problems you notice and any questions or concerns you have.

If you are still taking mitotane, your follow-up appointments may need to be more frequent to see if the mitotane levels in your blood are in a good range and if there are any side effects from this drug. Remember that mitotane will also suppress the usual adrenal steroid hormone production from your other, normal adrenal gland. As a result, you will need to take hormone replacement tablets to protect you against cortisol deficiency.

CT scans may be done periodically to see if the cancer has returned or is continuing to grow. Periodic tests of your blood and urine hormone levels will be done to evaluate the success of drugs in suppressing hormone production by the cancer.

Nutrition

Eating right can be hard for anyone, and may have gotten tougher during cancer treatment. The cancer, varying hormone levels, and your treatment can all affect how you eat and absorb nutrition. Nausea can be a problem during and after some treatments, and you may have lost your appetite and some weight.

If you have lost or are losing weight, or if you are having trouble eating, do the best you can. Eat what appeals to you. Eat what you can, when you can. You might find it helps to eat small portions every 2 to 3 hours until you feel better. Now is not the time to restrict your diet. Try to keep in mind that these problems usually improve over time. Your cancer team may refer you to a dietitian, an expert in nutrition who can give you ideas on how to fight some of the side effects of your treatment.

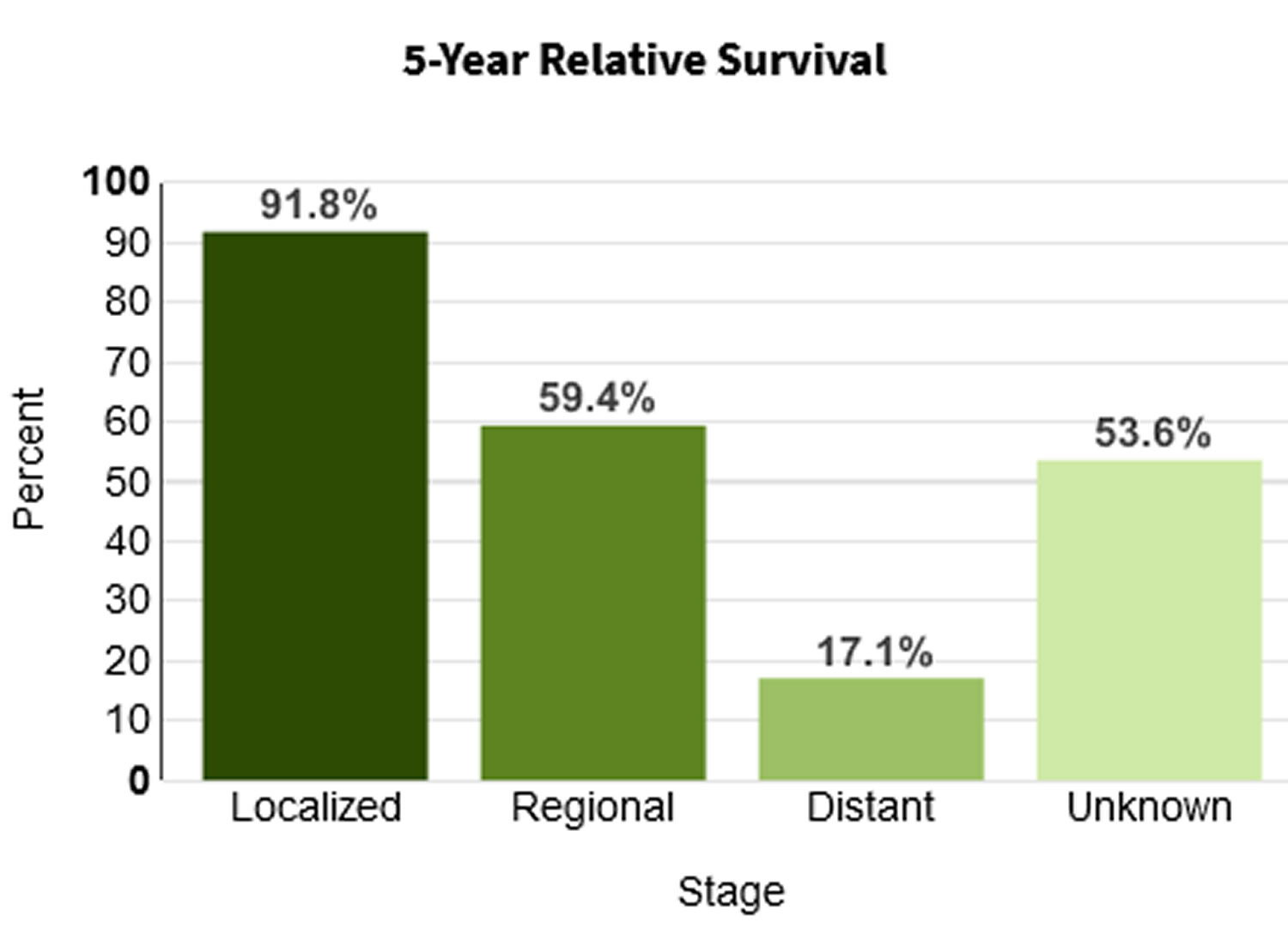

Adrenal cortical carcinoma life expectancy

The overall prognosis (outcome) of adrenal cortical carcinoma depends on how early the diagnosis is made and whether the tumor has spread (metastasized). Overall the prognosis of adrenal cortical carcinoma is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 40% 10, 39. Up to 70% of patients with the localized adrenal cortical carcinoma based on TNM staging experienced recurrence within 3 years after surgery 39, while the survival duration of patients with metastatic adrenal cortical carcinomas or adrenal cortical carcinoma that has spread ranges from several months to 10 years or more 40.

Table 2. 5-year relative survival rates for adrenal cancer

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) stage | 5-year relative survival rate |

|---|---|

| Localized | 73% |

| Regional | 53% |

| Distant | 38% |

| All SEER stages combined | 50% |

Footnotes: Survival rates can give you an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database tracks 5-year relative survival rates for adrenal cancer in the United States, based on how far the cancer has spread. The SEER database, however, does not group cancers by AJCC/ENSAT stages (stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, etc.). Instead, it groups cancers into localized, regional, and distant stages:

- Localized: There is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the adrenal gland.

- Regional: The cancer has spread outside the adrenal gland to nearby structures or lymph nodes.

- Distant: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body, such as the liver or lungs.

A relative survival rate compares people with the same type and stage of cancer to people in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of adrenal cancer is 73%, it means that people who have that cancer are, on average, about 73% as likely as people who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed.

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread. But other factors, such as your age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment, can also affect your outlook.

- People now being diagnosed with adrenal cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

Most recent reviews report 5-year survival for adults with adrenal cortical carcinoma after curative surgery around 20–50% 74, 75, 76. In children, 5-year survival has been reported to range from 30% to 70% with substantial variation based on disease presentation 5, 6, 51. For example, children with completely resected adrenal cortical carcinomas have a 5-year survival around 80–90% while those with metastatic disease have a 5-year survival closer to 0–20% 77, 55, 78, 5, 6, 41.

References- Mete O, Erickson LA, Juhlin CC, de Krijger RR, Sasano H, Volante M, Papotti MG. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Adrenal Cortical Tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2022 Mar;33(1):155-196. doi: 10.1007/s12022-022-09710-8

- Hodgson A, Pakbaz S, Mete O. A Diagnostic Approach to Adrenocortical Tumors. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019 Dec;12(4):967-995. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2019.08.005

- Adrenocortical carcinoma. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001663.htm

- Wooten MD, King DK. Adrenal cortical carcinoma. Epidemiology and treatment with mitotane and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1993 Dec 1;72(11):3145-55. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931201)72:11<3145::aid-cncr2820721105>3.0.co;2-n

- Michalkiewicz E, Sandrini R, Figueiredo B, Miranda EC, Caran E, Oliveira-Filho AG, Marques R, Pianovski MA, Lacerda L, Cristofani LM, Jenkins J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Ribeiro RC. Clinical and outcome characteristics of children with adrenocortical tumors: a report from the International Pediatric Adrenocortical Tumor Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Mar 1;22(5):838-45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.085

- Wieneke JA, Thompson LD, Heffess CS. Adrenal cortical neoplasms in the pediatric population: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 83 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003 Jul;27(7):867-81. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200307000-00001

- Redlich A, Boxberger N, Strugala D, Frühwald MC, Leuschner I, Kropf S, Bucsky P, Vorwerk P. Systemic treatment of adrenocortical carcinoma in children: data from the German GPOH-MET 97 trial. Klin Padiatr. 2012 Oct;224(6):366-71. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327579

- Gulack BC, Rialon KL, Englum BR, Kim J, Talbot LJ, Adibe OO, Rice HE, Tracy ET. Factors associated with survival in pediatric adrenocortical carcinoma: An analysis of the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB). J Pediatr Surg. 2016 Jan;51(1):172-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.10.039

- Kebebew E., Reiff E., Duh Q.Y., Clark O.H., McMillan A. Extent of disease at presentation and outcome for adrenocortical carcinoma: Have we made progress? World J. Surg. 2006;30:872–878. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0329-x

- Kerkhofs T.M., Verhoeven R.H., Van der Zwan J.M., Dieleman J., Kerstens M.N., Links T.P., Van de Poll-Franse L.V., Haak H.R. Adrenocortical carcinoma: A population-based study on incidence and survival in the Netherlands since 1993. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49:2579–2586. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.034

- Berstein L, Gurney JG: Carcinomas and other malignant epithelial neoplasms. In: Ries LA, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al., eds.: Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, 1999. NIH Pub.No. 99-4649, Chapter 11, pp 139-148.

- Rodriguez-Galindo C: Adrenocortical tumors in children. In: Schneider DT, Brecht IB, Olson TA: Rare Tumors in Children and Adolescents. Springer-Verlag, 2012, pp 436-44.

- Figueiredo BC, Sandrini R, Zambetti GP, Pereira RM, Cheng C, Liu W, Lacerda L, Pianovski MA, Michalkiewicz E, Jenkins J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Mastellaro MJ, Vianna S, Watanabe F, Sandrini F, Arram SB, Boffetta P, Ribeiro RC. Penetrance of adrenocortical tumours associated with the germline TP53 R337H mutation. J Med Genet. 2006 Jan;43(1):91-6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030551

- Pianovski, M.A.D., Maluf, E.M.C.P., de Carvalho, D.S., Ribeiro, R.C., Rodriguez-Galindo, C., Boffetta, P., Zancanella, P. and Figueiredo, B.C. (2006), Mortality rate of adrenocortical tumors in children under 15 years of age in Curitiba, Brazil. Pediatr. Blood Cancer, 47: 56-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20624

- Rodriguez-Galindo, C., Figueiredo, B.C., Zambetti, G.P. and Ribeiro, R.C. (2005), Biology, clinical characteristics, and management of adrenocortical tumors in children. Pediatr. Blood Cancer, 45: 265-273. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20318

- Adrenocortical carcinoma. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/558/adrenocortical-carcinoma

- Vaidya A., Nehs M., Kilbridge K. Treatment of Adrenocortical Carcinoma. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2019;12:997–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2019.08.010

- Nakamura Y., Yamazaki Y., Felizola S.J., Ise K., Morimoto R., Satoh F., Arai Y., Sasano H. Adrenocortical carcinoma: Review of the pathologic features, production of adrenal steroids, and molecular pathogenesis. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2015;44:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2015.02.007

- Puglisi S., Perotti P., Pia A., Reimondo G., Terzolo M. Adrenocortical Carcinoma with Hypercortisolism. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2018;47:395–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2018.02.003

- Simonds W.F., Varghese S., Marx S.J., Nieman L.K. Cushing’s syndrome in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Clin. Endocrinol. 2012;76:379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04220.x

- Domènech M., Grau E., Solanes A., Izquierdo A., Del Valle J., Carrato C., Pineda M., Dueñas N., Pujol M., Lázaro C., et al. Characteristics of Adrenocortical Carcinoma Associated With Lynch Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021;106:318–325. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa833

- Ferreira A.M., Brondani V.B., Helena V.P., Charchar H.L.S., Zerbini M.C.N., Leite L.A.S., Hoff A.O., Latronico A.C., Mendonca B.B., Diz M.D.P.E., et al. Clinical spectrum of Li-Fraumeni syndrome/Li-Fraumeni-like syndrome in Brazilian individuals with the TP53 p.R337H mutation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019;190:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.04.011

- Menon R.K., Ferrau F., Kurzawinski T.R., Rumsby G., Freeman A., Amin Z., Korbonits M., Chung T.-T.L.L. Adrenal cancer in neurofibromatosis type 1: Case report and DNA analysis. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2014;2014:140074. doi: 10.1530/EDM-14-0074

- Anselmo J., Medeiros S., Carneiro V., Greene E., Levy I., Nesterova M., Lyssikatos C., Horvath A., Carney J.A., Stratakis C.A. A large family with Carney complex caused by the S147G PRKAR1A mutation shows a unique spectrum of disease including adrenocortical cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:351–359. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2244

- Traill Z., Tuson J., Woodham C. Adrenal carcinoma in a patient with Gardner’s syndrome: Imaging findings. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1995;165:1460–1461. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.6.7484586

- Pakalniskis M.G., Ishigami K., Pakalniskis B.L., Fujita N. Adrenal collision tumour comprised of adrenocortical carcinoma and myelolipoma in a patient with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2020;64:67–68. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12961

- Łebek-Szatańska A., Nowak K.M., Samsel R., Roszkowska-Purska K., Zgliczyński W., Papierska L. Adrenocortical carcinoma associated with giant bilateral myelolipomas in classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2019;129:549–550. doi: 10.20452/pamw.14788

- Varma T., Panchani R., Goyal A., Maskey R. A case of androgen-secreting adrenal carcinoma with non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;17:S243–S245. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.119585

- Lam AK. Adrenocortical Carcinoma: Updates of Clinical and Pathological Features after Renewed World Health Organisation Classification and Pathology Staging. Biomedicines. 2021 Feb 10;9(2):175. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9020175

- Lodish M. Genetics of Adrenocortical Development and Tumors. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2017;46:419–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2017.01.007

- Creemers S.G., van Koetsveld P.M., van Kemenade F.J., Papathomas T.G., Franssen G.J.H., Dogan F., Eekhoff E.M., van der Valk P., de Herder W.W., Janssen J.A., et al. Methylation of IGF2 regulatory regions to diagnose adrenocortical carcinomas. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2016;23:727–737. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0266

- Szyszka P, Grossman AB, Diaz-Cano S, Sworczak K, Dworakowska D. Molecular pathways of human adrenocortical carcinoma – translating cell signalling knowledge into diagnostic and treatment options. Endokrynol Pol. 2016;67(4):427-50. doi: 10.5603/EP.a2016.0054

- Mizdrak M, Tičinović Kurir T, Božić J. The Role of Biomarkers in Adrenocortical Carcinoma: A Review of Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2021 Feb 10;9(2):174. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9020174). TP53 plays a role in regulation of the cell cycle, apoptosis, genomic stability and activation of DNA repair proteins. It is the most frequently altered gene in sporadic cancers ((Mizdrak M, Tičinović Kurir T, Božić J. The Role of Biomarkers in Adrenocortical Carcinoma: A Review of Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2021 Feb 10;9(2):174. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9020174

- Pereira S.S., Monteiro M.P., Bourdeau I., Lacroix A., Pignatelli D. Mechanisms of endocrinology: Cell cycle regulation in adrenocortical carcinoma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2018;179:R95–R110. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-0976

- Wanis K.N., Kanthan R. Diagnostic and prognostic features in adrenocortical carcinoma: A single institution case series and review of the literature. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2015;13:117. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0527-4

- Allolio B, Fassnacht M: Clinical presentation and initial diagnosis. In: Hammer GD, Else T, eds.: Adrenocortical Carcinoma: Basic Science and Clinical Concepts. Springer, 2010, pp 31-47.