What is cortisol

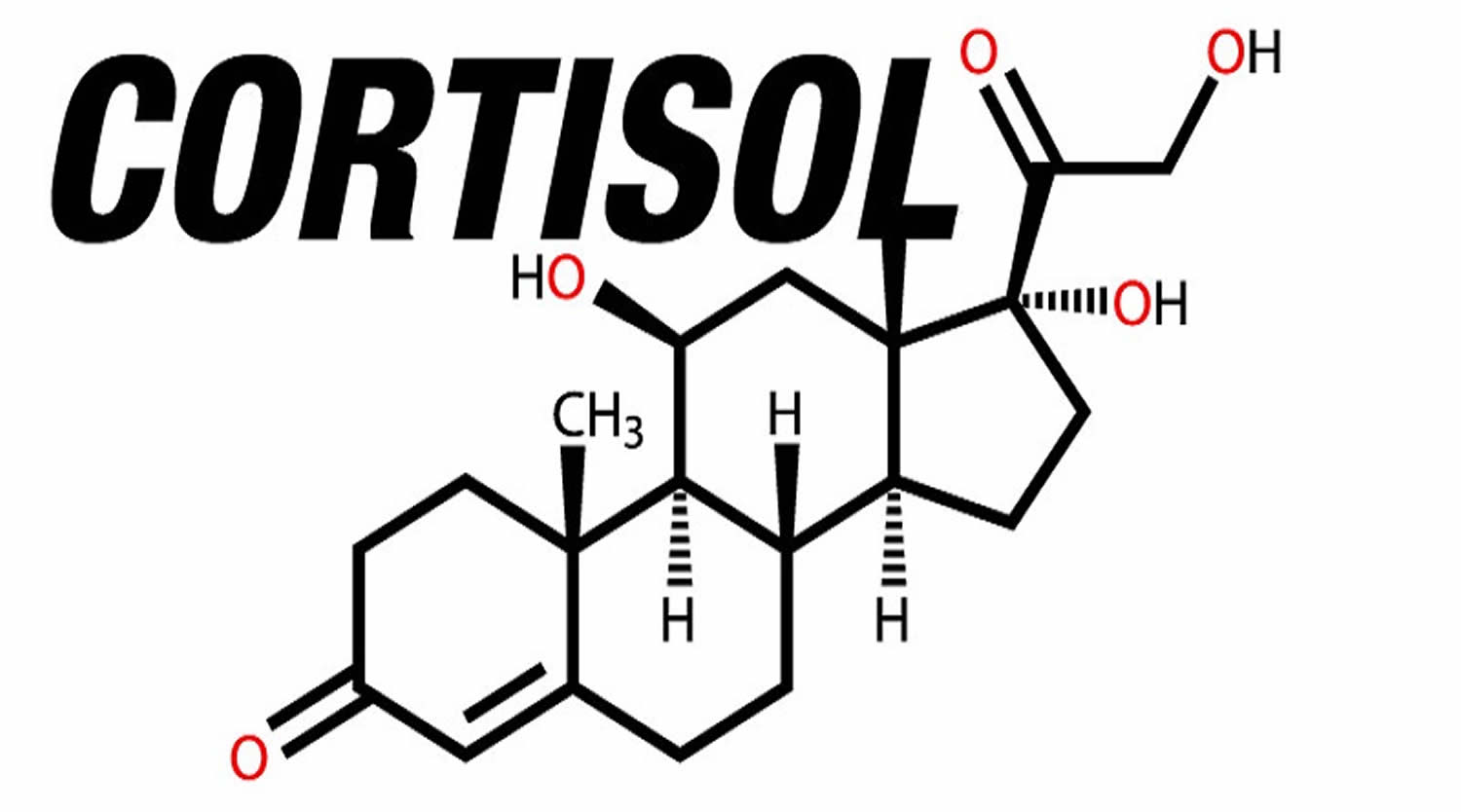

Cortisol is a steroid hormone also known as hydrocortisone that is often called the “stress hormone” because of its connection to the stress response, however, cortisol is much more than just a hormone released during stress. Cortisol is produced by the adrenal glands which sit on top of each kidney (Figures 1 and 2).

Cortisol production by the adrenal glands is regulated by the pituitary gland. The pituitary is a pea-sized gland at the base of the brain that is sometimes referred to as the “master gland” because of its wider effects on the body.

When you wake up, exercise or you’re facing a stressful event, your pituitary gland reacts. It sends a signal to the adrenal glands to produce just the right quantity of cortisol.

When released into the bloodstream, cortisol can act on many different parts of the body and can help:

- Your body respond to stress or danger

- Increase your body’s metabolism of fats, carbohydrates, and protein

- Regulate metabolism, the process of how your body uses food and energy

- Regulate blood sugar

- Control your blood pressure

- Control bone growth

- Regulate immune system function and reduce inflammation and fight infection

- Nervous system function.

Cortisol is a hormone that plays a role in the metabolism of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. Cortisol affects blood glucose levels, helps maintain blood pressure, and helps regulate the immune system.

Cortisol is also needed for the fight or flight response which is a healthy, natural response to perceived threats. The amount of cortisol produced is highly regulated by your body to ensure the balance is correct.

Most cortisol in the blood is bound to a protein; only a small percentage is “free” and biologically active. Free cortisol is secreted into the urine and is present in the saliva. This test measures the amount of cortisol in the blood, urine, or saliva.

Most cells within the body have cortisol receptors. Secretion of the hormone is controlled by the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal gland, a combination glands often referred to as the hypothalamic pituitary axis. When the hypothalamus produces corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH), it stimulates the pituitary gland to release adrenal corticotrophic hormone (ACTH) (see Figure 5). These hormones, in turn, alert the adrenal glands to produce corticosteroid hormones (e.g. cortisol and corticosterone).

Cortisol is produced and secreted by the adrenal glands, two triangular organs that sit on top of the kidneys (Figure 2). Production of the hormone is regulated by the hypothalamus in the brain and by the pituitary gland, a tiny organ located below the brain (Figure 1, 3, 4 and 5). When the blood cortisol level falls, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which directs the pituitary gland to produce ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone). ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to produce and release cortisol. In order for appropriate amounts of cortisol to be made, the hypothalamus, the pituitary, and the adrenal glands must be functioning properly.

What happens when you produce too much or little cortisol?

Your body usually produces the right amount of cortisol. In a condition such as Cushing’s syndrome, it produces too much. In a condition such as Addison’s disease, it produces too little.

Symptoms of too much cortisol include:

- weight gain, particularly around the abdomen and face

- thin and fragile skin that is slow to heal

- acne

- for women, facial hair and irregular menstrual periods.

Symptoms of not enough cortisol include:

- continual tiredness

- nausea and vomiting

- weight loss

- muscle weakness

- pain in the abdomen.

If you experience any of these symptoms, your doctor may suggest you have a blood test to measure your cortisol levels.

If your body does not produce enough cortisol, your doctor may prescribe corticosteroids for you. Corticosteroids are synthetic versions of cortisol that can be used to treat a variety of conditions including:

- inflammatory conditions (such as asthma)

- Addison’s disease

- skin conditions (such as psoriasis).

Some people take anabolic steroids to build muscles, without a doctor’s prescription. This is risky. Anabolic steroids are different to corticosteroids.

Because corticosteroids are powerful medications, side effects are quite common. These may include:

- thinning skin

- osteoporosis

- weight gain, especially around the face, and increased appetite

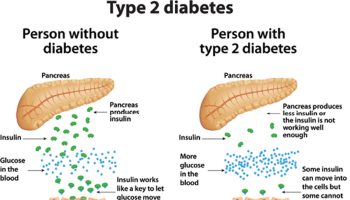

- high blood sugar or diabetes

- rapid mood changes, feeling irritable and anxious

- an increased chance of infections like chickenpox or measles

- Cushing’s syndrome

- eye conditions, such as glaucoma and cataracts

- depression or suicidal thoughts

- high blood pressure.

If you experience these side effects, it is important to talk to your doctor before stopping your medication.

Figure 1. Location of the adrenal glands on top of each kidneys

Figure 3. The pituitary gland location

Figure 4. Pituitary gland

Figure 5. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland (anterior and posterior) endocrine pathways and target organs

Cortisol function

Cortisol is a hormone, which is mainly released at times of stress and has many important functions in your body. Having the right cortisol balance is essential for human health and you can have problems if your adrenal gland releases too much or too little cortisol.

Cortisol regulates how the body converts fats, proteins, and carbohydrates to energy. Cortisol also helps regulate blood pressure and cardiovascular function.

What does cortisol do?

The more important actions of cortisol include:

- Inhibition of protein synthesis in tissues, increasing the blood concentration of amino acids.

- Promotion of fatty acid release from adipose tissue, increasing the utilization of fatty acids and decreasing the use of glucose as energy sources.

- Stimulation of liver cells to synthesize glucose from non-carbohydrates, such as circulating amino acids and glycerol, increasing the blood glucose concentration.

These actions of cortisol help keep blood glucose concentration within the normal range between meals. This control is important, because a few hours without food can exhaust the supply of liver glycogen, a major source of glucose.

Negative feedback controls cortisol release. This is much like control of thyroid hormones, involving the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary gland, and adrenal cortex. The hypothalamus secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) into the pituitary gland portal veins, which carry CRH to the anterior pituitary, stimulating it to secrete adrenal corticotrophic hormone (ACTH). In turn, ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex to release cortisol. Cortisol inhibits the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone), and as concentrations of these fall, cortisol production drops.

The set point of the feedback mechanism controlling cortisol secretion may change to meet the demands of changing conditions. For example, under stress—as from injury, disease, or emotional upset—information concerning the stressful condition reaches the brain. In response, brain centers signal the hypothalamus to release more corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), elevating the blood cortisol concentration until the stress subsides.

Figure 6. Negative feedback regulates cortisol secretion

Cortisol test

A cortisol test is used to help diagnose disorders of the adrenal gland. These include Cushing’s syndrome, a condition that causes your body to make too much cortisol, and Addison disease, a condition in which your body doesn’t make enough cortisol.

A cortisol test may be ordered when a person has symptoms that suggest a high level of cortisol and Cushing syndrome, such as:

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High blood sugar (glucose)

- Obesity, especially in the trunk

- Fragile skin

- Purple streaks on the abdomen

- Muscle wasting and weakness

- Osteoporosis

Testing may be ordered when women have irregular menstrual periods and increased facial hair; children may have delayed development and a short stature.

Cortisol test may be ordered when someone has symptoms suggestive of a low level of cortisol, adrenal insufficiency or Addison disease, such as:

- Weight loss

- Muscle weakness

- Fatigue

- Low blood pressure

- Abdominal pain

- Dark patches of skin (this occurs in Addison disease but not secondary adrenal insufficiency)

You may also need a cortisol test if you have symptoms of an adrenal crisis, a life-threatening condition that can happen when your cortisol levels are extremely low. Symptoms of an adrenal crisis include:

- Very low blood pressure

- Severe vomiting

- Severe diarrhea

- Dehydration

- Sudden and severe pain in the abdomen, lower back, and legs

- Confusion

- Loss of consciousness

Suppression or stimulation testing is ordered when initial findings are abnormal. Cortisol testing may be ordered at intervals after a diagnosis of Cushing syndrome or Addison disease to monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

Cortisol blood test

Typically, blood will be drawn from a vein in your arm, but sometimes urine or saliva may be tested. Cortisol blood tests may be drawn at about 8 am, when cortisol should be at its peak, and again at about 4 pm, when the level should have dropped significantly.

Sometimes a resting sample will be obtained to measure cortisol when it should be at its lowest level (just before sleep); this is often done by measuring cortisol in saliva rather than blood to make it easier to obtain the sample. Saliva for cortisol testing is usually collected by inserting a swab into the mouth and waiting a few minutes while the swab becomes saturated with saliva. Obtaining more than one sample allows the health practitioner to evaluate the daily pattern of cortisol secretion (the diurnal variation).

Sometimes urine is tested for cortisol; this usually requires collecting all of the urine produced during a day and night (a 24-hour urine) but sometimes may be done on a single sample of urine collected in the morning.

Some test preparation may be needed. Follow any instructions that are given as far as timing of sample collection, resting, and/or any other specific pre-test preparation.

A stimulation or suppression test requires that you have a baseline blood sample drawn and then a specified amount of drug is given. Subsequent blood samples are drawn at specified times.

Will I need to do anything to prepare for the test?

Stress can raise your cortisol levels, so you may need to rest before your test. A blood test will require you to schedule two appointments at different times of the day. Twenty-four hour urine and saliva tests are done at home. Be sure to follow all the instructions given by your provider.

What do the results mean?

High levels of cortisol may mean you have Cushing’s syndrome, while low levels may mean you have Addison disease or another type of adrenal disease. If your cortisol results are not normal, it doesn’t necessarily mean you have a medical condition needing treatment. Other factors, including infection, stress, and pregnancy can affect your results. Birth control pills and other medicines can also affect your cortisol levels. To learn what your results mean, talk to your health care provider.

Is there anything else I need to know about a cortisol test?

If your cortisol levels are not normal, your health care provider will likely order more tests before making a diagnosis. These tests may include additional blood and urine tests and imaging tests, such as CT (computerized tomography) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans, which allow your provider to look at your adrenal and pituitary glands.

Cortisol saliva test

A cortisol saliva test is usually done at home, late at night, when cortisol levels are lower. Your health care provider will recommend or provide you with a kit for this test. The kit will likely include a swab to collect your sample and a container to store it. A saliva test requires special care in obtaining the sample. Steps usually include the following:

- Do not eat, drink, or brush your teeth for 15-30 minutes before the test.

- Collect the sample between 11 p.m. and midnight, or as instructed by your provider.

- Put the swab into your mouth.

- Roll the swab in your mouth for about 2 minutes so it can get covered in saliva.

- Don’t touch the tip of the swab with your fingers.

- Put the swab into the container within the kit and return it to your provider as instructed.

Follow any specific instructions that are provided. Salivary cortisol testing is being used more frequently to help diagnose Cushing syndrome and stress-related disorders but still requires specialized expertise to perform.

Cortisol urine test

The cortisol urine test measures the level of cortisol in the urine.

Cortisol can also be measured using a blood or saliva test.

A 24-hour urine sample is needed. You will need to collect your urine over 24 hours in a container provided by the laboratory. Your health care provider will tell you how to do this. Follow instructions exactly.

Because cortisol level rises and falls throughout the day, the test may need to be done three or more separate times to get a more accurate picture of average cortisol production.

How to prepare for the urine test

You may be asked not to do any vigorous exercising the day before the test.

You may also be told to temporarily stop taking medicines that can affect the test, including:

- Anti-seizure drugs

- Estrogen

- Human-made (synthetic) glucocorticoids, such as hydrocortisone, prednisone and prednisolone

- Androgens

Do I need both tests (blood and urine) or is one better than the other?

If your healthcare provider suspects Cushing syndrome, usually both blood and urine are tested as they offer complementary information. Blood cortisol is easier to collect but is affected more by stress than is the 24-hour urine test. Salivary cortisol may sometimes be tested instead of blood cortisol.

Testing for Excess Cortisol Production

If a person has a high blood cortisol level, a health practitioner may perform additional testing to confirm that the high cortisol is truly abnormal (and not simply due to increased stress or the use of cortisol-like medication). This additional testing may include measuring the 24-hour urinary cortisol, doing an overnight dexamethasone suppression test, and/or collecting a salivary sample before retiring in order to measure cortisol at the time that it should be the lowest. Urinary cortisol requires the collection of urine over a timed period, usually 24 hours. Since ACTH is secreted by the pituitary gland in pulses, this test helps determine whether the elevated blood cortisol level represents a real increase.

Dexamethasone suppression: The dexamethasone suppression test involves analyzing a baseline sample for cortisol, then giving the person oral dexamethasone (a synthetic glucocorticoid) and measuring cortisol levels in subsequent timed samples. Dexamethasone suppresses ACTH production and should decrease cortisol production if the source of the excess is stress.

Collecting a salivary sample for cortisol measurement is a convenient way to determine whether the normal rhythm of cortisol production is altered. If one or more of these tests confirms that there is abnormal cortisol production, then additional testing, including measuring ACTH, repeating the dexamethasone suppression test using higher doses, and radiologic imaging may be ordered.

Dexamethasone suppression test (also called ACTH suppression test or Cortisol suppression test) measures whether adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) secretion by the pituitary can be suppressed.

How the dexamethasone test is performed

During this test, you will receive dexamethasone. This is a strong man-made (synthetic) glucocorticoid medicine. Afterward, your blood is drawn so that the cortisol level in your blood can be measured.

There are two different types of dexamethasone suppression tests: low dose and high dose. Each type can either be done in an overnight (common) or standard (3-day) method (rare). There are different processes that may be used for either test. Examples of these are described below.

Common:

- Low-dose overnight — You will get 1 milligram (mg) of dexamethasone at 11 p.m., and a health care provider will draw your blood the next morning at 8 a.m. for a cortisol measurement.

- High-dose overnight — The provider will measure your cortisol on the morning of the test. Then you will receive 8 mg of dexamethasone at 11 p.m. Your blood is drawn the next morning at 8 a.m. for a cortisol measurement.

Rare:

- Standard low-dose — Urine is collected over 3 days (stored in 24-hour collection containers) to measure cortisol. On day 2, you will get a low dose (0.5 mg) of dexamethasone by mouth every 6 hours for 48 hours.

- Standard high-dose — Urine is collected over 3 days (stored in 24-hour collection containers) for measurement of cortisol. On day 2, you will receive a high dose (2 mg) of dexamethasone by mouth every 6 hours for 48 hours.

Read and follow the instructions carefully. The most common cause of an abnormal test result is when instructions are not followed.

How to prepare for the dexamethasone test

The provider may tell you to stop taking certain medicines that can affect the test, including:

- Antibiotics

- Anti-seizure drugs

- Medicines that contain corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone, prednisone

- Estrogen

- Oral birth control (contraceptives)

- Water pills (diuretics)

How the dexamethasone test will feel

When the needle is inserted to draw blood, some people feel moderate pain. Others feel only a prick or stinging. Afterward, there may be some throbbing or slight bruising. This soon goes away.

Why the dexamethasone test is performed

This test is done when the provider suspects that your body is producing too much cortisol. It is done to help diagnose Cushing syndrome and identify the cause.

The low-dose test can help tell whether your body is producing too much ACTH. The high-dose test can help determine whether the problem is in the pituitary gland (Cushing disease).

Dexamethasone is a man-made (synthetic) steroid that is similar to cortisol. It reduces ACTH release in normal people. Therefore, taking dexamethasone should reduce ACTH level and lead to a decreased cortisol level.

If your pituitary gland produces too much ACTH, you will have an abnormal response to the low-dose test. But you can have a normal response to the high-dose test.

Normal Results

Cortisol level should decrease after you receive dexamethasone.

Low dose:

- Overnight — 8 a.m. plasma cortisol lower than 1.8 micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL) or 50 nanomoles per liter (nmol/L)

- Standard — Urinary free cortisol on day 3 lower than 10 micrograms per day (mcg/day) or 280 nmol/L

High dose:

- Overnight — greater than 50% reduction in plasma cortisol

- Standard — greater than 90% reduction in urinary free cortisol

Normal value ranges may vary slightly among different laboratories. Some labs use different measurements or may test different specimens. Talk to your doctor about the meaning of your specific test results.

What Abnormal Results Mean

An abnormal response to the low-dose test may mean that you have abnormal release of cortisol (Cushing syndrome). This could be due to:

- Adrenal tumor that produces cortisol

- Pituitary tumor that produces ACTH

- Tumor in the body that produces ACTH (ectopic Cushing syndrome)

The high-dose test can help tell a pituitary cause (Cushing disease) from other causes. An ACTH blood test may also help identify the cause of high cortisol.

Abnormal results vary based on the condition causing the problem.

Cushing syndrome caused by an adrenal tumor:

- Low-dose test — no decrease in blood cortisol

- ACTH level — low

- In most cases, the high-dose test is not needed

Ectopic Cushing syndrome:

- Low-dose test — no decrease in blood cortisol

- ACTH level — high

- High-dose test — no decrease in blood cortisol

Cushing syndrome caused by a pituitary tumor (Cushing disease)

- Low-dose test — no decrease in blood cortisol

- High-dose test — expected decrease in blood cortisol

False test results can occur due to many reasons, including different medicines, obesity, depression, and stress.

Risks of Dexamethasone suppression test

Veins and arteries vary in size from one patient to another, and from one side of the body to the other. Obtaining a blood sample from some people may be more difficult than from others.

Other risks associated with having blood drawn are slight, but may include:

- Excessive bleeding

- Fainting or feeling lightheaded

- Hematoma (blood accumulating under the skin)

- Infection (a slight risk any time the skin is broken).

Testing for Insufficient Cortisol Production

If a health practitioner suspects that the adrenal glands may not be producing adequate cortisol or if the initial blood tests indicate insufficient cortisol production, the health practitioner may order an ACTH stimulation test.

ACTH stimulation: This test involves measuring the level of cortisol in a person’s blood before and after an injection of synthetic ACTH. If the adrenal glands are functioning normally, then cortisol levels will rise with the ACTH stimulation. If they are damaged or not functioning properly, then the cortisol level will be low. A longer version of this test (1-3 days) may be performed to help distinguish between adrenal and pituitary insufficiency.

Cortisol levels

The level of cortisol in the blood (as well as the urine and saliva) normally rises and falls in a “diurnal variation” pattern. Cortisol peaks early in the morning, then declines throughout the day, reaching its lowest level about midnight. Though this pattern can change when a person works irregular shifts (such as the night shift) and sleeps at different times of the day, and it can become disrupted when a disease or condition either limits or stimulates cortisol production.

An increased or normal cortisol level just after waking along with a level that does not drop by bedtime suggests excess cortisol and Cushing syndrome. If this excess cortisol is not suppressed after an overnight dexamethasone suppression test, or if the 24-hour urine cortisol is elevated, or if the late-night salivary cortisol level is elevated, it suggests that the excess cortisol is due to abnormal increased ACTH production by the pituitary or a tumor outside of the pituitary or abnormal production by the adrenal glands. Additional testing will help to determine the exact cause.

If insufficient cortisol is present and the person tested responds to an ACTH stimulation test, then the problem is likely due to insufficient ACTH production by the pituitary. If the person does not respond to the ACTH stimulation test, then it is more likely that the problem is based in the adrenal glands. If the adrenal glands are underactive, due to pituitary dysfunction and/or insufficient ACTH production, then the person is said to have secondary adrenal insufficiency. If decreased cortisol production is due to adrenal damage, then the person is said to have primary adrenal insufficiency or Addison disease.

Once an abnormality has been identified and associated with the pituitary gland, adrenal glands, or other cause, then the health practitioner may use other testing such as CT (computerized tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans to locate the source of the excess (such as a pituitary, adrenal, or other tumor) and to evaluate the extent of any damage to the glands.

Figure 7. Cortisol levels

Footnotes: Circadian rhythm of cortisol in 33 individuals with 20-minute cortisol profiling. Peak cortisol levels are reached at around 08:30 and nadir cortisol levels at around midnight. The peaks of cortisol at noon and around 18:00 represent meal-induced cortisol stimulation.

[Source 1]Cortisol production rate

A number of cortisol secretory episodes occur during the 24 hour of the day making it possible to describe four different unequal temporal phases. These phases are represented by a period of minimal secretory activity, during which cortisol secretion is negligible, and occurs 4 hours prior to and 2 hours after sleep onset, a preliminary nocturnal secretory episode at the third through fifth hours of sleep, a main secretory phase of a series of three to five episodes occurring during the sixth to eighth hours of sleep and continuing through the first hour of wakefulness and an intermittent waking secretory activity of four to nine secretory episodes found in the 2–12-hour waking period 2. Advances in the measurement of the total amount of cortisol produced in a day shows that this is around 5.7–7.4 mg/m²/day or 9.5–9.9 mg/day 3 which is much less than previous estimates. Cortisol production rates in children and adolescents are very similar. These findings support regimes with lower oral daily hydrocortisone doses of 15–25 mg 4.

The regulation of cortisol release, is critically determined by the activity of the hypothalamic pituitary axis. The hypothalamic pituitary axis receives input from the central pacemaker which controls the circadian release of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) in the paraventricular nucleus, this also stimulated by physical and emotional stressors. CRH in turn stimulates release of adrenocorticotrophic hormones (ACTH) from the corticotroph cells in the anterior pituitary, and thence the glucocorticoid cortisol from the adrenal cortex. In turn, cortisol exerts inhibitory effects at pituitary and hypothalamic levels, in a classical negative feedback loop although there is no feedback on the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nuclei 5.

The adrenal gland contains a circadian clock that sets specific time intervals during which the adrenal most effectively responds to ACTH. This is regulated via the splanchnic nerve 6. Clock genes are expressed rhythmically in the zona glomerulosa and zona fasciculata, and entire pathways characteristic for the adrenal gland, such as steroid metabolism or catecholamine production, are transcriptionally regulated by the circadian clock 7. Expression of clock genes in the adrenal gland shows a 6-hour phase delay relative to the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nuclei which is mainly induced via the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nuclei—sympathetic nervous system without accompanying activation of the hypothalamic pituitary axis axis 8. This gene expression accompanies the rhythmic secretion of plasma and brain cortisol.

Normal cortisol levels

Adults have slightly higher cortisol levels than children do.

Normal blood cortisol levels

Normal values for a blood sample taken at 8 in the morning are 5 to 25 mcg/dL or 140 to 690 nmol/L.

Normal values depend on the time of day and the clinical context. Normal ranges may vary slightly among different laboratories. Some labs use different measurements or may test different specimens. Talk to your doctor about the meaning of your specific test results.

What does abnormal cortisol levels mean?

A higher than normal level may indicate:

- Cushing disease, in which the pituitary gland makes too much ACTH because of excess growth of the pituitary gland or a tumor in the pituitary gland

- Ectopic Cushing syndrome, in which a tumor outside the pituitary or adrenal glands makes too much ACTH

- Tumor of the adrenal gland that is producing too much cortisol

A lower than normal cortisol level may indicate:

- Addison disease, in which the adrenal glands do not produce enough cortisol

- Hypopituitarism, in which the pituitary gland does not signal the adrenal gland to produce enough cortisol

- Suppression of normal pituitary or adrenal function by glucocorticoid medicines including pills, skin creams, eyedrops, inhalers, joint injections, chemotherapy

Normal urine levels

Normal range is 4 to 40 mcg/24 hours or 11 to 110 nmol/day.

Normal value ranges may vary slightly among different laboratories. Some labs use different measurements or may test different specimens. Talk to your provider about the meaning of your specific test results.

What does abnormal cortisol levels mean?

A higher than normal urine cortisol level may indicate:

- Cushing disease, in which the pituitary gland makes too much ACTH because of excess growth of the pituitary gland or a tumor in the pituitary gland

- Ectopic Cushing syndrome, in which a tumor outside the pituitary or adrenal glands makes too much ACTH

- Severe depression

- Tumor of the adrenal gland that is producing too much cortisol

- Severe stress

- Rare genetic disorders

A lower than normal level may indicate:

- Addison disease in which the adrenal glands do not produce enough cortisol

- Hypopituitarism in which the pituitary gland does not signal the adrenal gland to produce enough cortisol

- Suppression of normal pituitary or adrenal function by glucocorticoid medicines including pills, skin creams, eyedrops, inhalers, joint injections, chemotherapy.

High cortisol levels

The group of signs and symptoms that are seen with an abnormally high level of cortisol is called Cushing syndrome. Increased cortisol production may be seen with:

- Administration of large amounts of glucocorticosteroid hormones (such as prednisone, prednisolone, or dexamethasone) to treat a variety of conditions, such as autoimmune disease and some tumors

- ACTH-producing tumors, in the pituitary gland and/or in other parts of the body

- Increased cortisol production by the adrenal glands, due to a tumor or due to excessive growth of adrenal tissues (hyperplasia)

- Rarely, with tumors in various parts of the body that produce corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)

- Heat, cold, infection, trauma, exercise, obesity, and debilitating disease can influence cortisol concentrations. Pregnancy, physical and emotional stress, and illness can increase cortisol levels. Cortisol levels may also increase as a result of hyperthyroidism or obesity. A number of drugs can also increase levels, particularly oral contraceptives (birth control pills), hydrocortisone (the synthetic form of cortisol), and spironolactone.

What is Cushing syndrome

Cushing syndrome (also sometimes called Cushing’s syndrome) is a condition where your body is exposed to too much of the hormone cortisol. This can be because your body is making too much cortisol, or because you have taken a lot of oral corticosteroid medicines. If you have Cushing’s syndrome, it is treatable. However Cushing’s syndrome can be serious if it’s not treated. The condition is named after Harvey Cushing, an eminent American neurosurgeon, who described the first patients with this condition in 1912.

Cortisol hormone has several important functions including:

- Cortisol helps to regulate blood pressure

- Cortisol helps to regulate the immune system

- Cortisol helps to balance the effect of insulin to keep blood sugar normal by converting fat, carbohydrates, and proteins into energy

- Cortisol helps the body to respond to stress

Cortisol is involved in many different parts of your body. It is produced all day, and especially during times of stress.

- Some people with Cushing’s syndrome have a benign tumor in part of the brain. This tumor tells the adrenal glands to release cortisol. This condition is known as Cushing’s disease.

- Other people develop Cushing’s syndrome from taking steroid medication for a long time. If you have Cushing’s syndrome as a result of taking steroid medication, do not stop taking it suddenly, as you could become very unwell. Talk to your doctor.

- Cushing’s syndrome can also be caused by a tumor of the adrenal gland, overgrowth of the adrenal glands, or occasionally a tumor somewhere else in the body.

Cushing’s syndrome is uncommon. It mostly affects people who have been taking steroid medicine, especially steroid tablets, for a long time. Steroids contain a man-made version of cortisol. For example taking a steroid such as prednisolone for asthma, arthritis or colitis.

Very rarely, it can be caused by the body producing too much cortisol. This is usually due to:

- a growth (tumor) in the pituitary gland in the brain

- a tumor in one of the adrenal glands above the kidneys

Strictly speaking, if the source of the problem is the pituitary gland, then the correct name is Cushing’s Disease.

The tumors are usually non-cancerous (benign). Far more women than men suffer from Cushing’s syndrome but it isn’t known why; it is most commonly diagnosed between the ages of 30 to 40. Although it is rare in children, some as young as 6 have been diagnosed. There are no environmental triggers known and it’s not hereditary.

Spontaneous Cushing’s syndrome, originating from within the body is rare, but occurs when the adrenal glands are making too much of a hormone called cortisol (the body’s natural glucocorticoid steroid hormone). The quoted incidence of Cushing’s syndrome is 1 in 200,000 but it is now being found more frequently when it is specifically investigated. The difficulty is that the symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome can be very wide ranging and thus the diagnosis may not necessarily be considered; it can be difficult to establish, at the earlier stages and this can cause a delay in diagnosis.

The commonest cause of spontaneous Cushing’s syndrome (around 70%) is a small benign tumor (growth) of the pituitary gland (a small gland at the base of the brain, behind the bridge of the nose). This produces the hormone called ACTH, (adrenocorticotrophic hormone), that goes through the blood stream to the adrenal glands and causes them to release too much cortisol. In this case there is a good chance that an operation on your pituitary gland will solve the problem. Alternatively, there could be a small growth in another part of your body which is having the same effect (this is called ectopic ACTH). If so, removing this growth will usually solve the problem. Lastly, there may be a small growth in one of the adrenal glands themselves, in which case an operation will be needed to remove that gland. In some circumstances it may be necessary to remove both adrenal glands to solve the problem.

Cushing syndrome causes

There are two types of Cushing syndrome:

- Exogenous (caused by factors outside the body) and

- Endogenous (caused by factors within the body).

The symptoms for both are the same. The only difference is how they are caused.

The most common is exogenous Cushing syndrome and is found in people taking cortisol-like medications such as prednisone. These drugs are used to treat inflammatory disorders such as asthma and rheumatoid arthritis. They also suppress the immune system after an organ transplant. This type of Cushing is temporary and goes away after the patient has finished taking the cortisol-like medications.

Endogenous Cushing syndrome, in which the adrenal glands produce too much cortisol, is uncommon. It usually comes on slowly and can be difficult to diagnose. This type of Cushing syndrome is most often caused by hormone-secreting tumors of the adrenal glands or the pituitary, a gland located at the base of the brain. In the adrenal glands, the tumor (usually non-cancerous) produces too much cortisol. In the pituitary, the tumor produces too much ACTH—the hormone that tells the adrenal glands to make cortisol. When the tumors form in the pituitary, the condition is often called Cushing disease.

Most tumors that produce ACTH originate in the pituitary but sometimes non-pituitary tumors, usually in the lungs, can also produce too much ACTH and cause Cushing syndrome.

Figure 8. Signs and symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome

High cortisol symptoms

Symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome include:

- Obesity, especially in the torso

- High blood pressure

- High blood sugar

- Purple streaks on the stomach

- Skin that bruises easily

- Muscle weakness

- Women may have irregular menstrual periods and excess hair on the face

Symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome can start suddenly or gradually. They tend to get slowly worse if not treated.

One of the main signs is weight gain and more body fat, such as:

- increased fat on your chest, shoulders and neck and tummy, but slim arms and legs

- a build-up of fat on the back of your neck and shoulders – known as a “buffalo hump”

- a red, puffy, rounded face

Other symptoms include:

- skin that bruises easily

- skin problems like slow healing of wounds

- large purple stretch marks on the tummy, hips and thighs

- weakness in your upper arms and thighs due to muscle loss

- a low libido and fertility problems

- irregular periods

- feeling tired or emotional

- depression and mood swings

- brittle bones or thin bones (osteoporosis)

- too much facial hair in women

Cushing’s syndrome can also cause high blood pressure (hypertension) and high blood sugar or diabetes, which can be serious if not treated.

Other symptoms include more hair on the face and body and a change in menstrual periods for women, and lower libido or erectile dysfunction for men.

Women with Cushing syndrome may experience:

- Thicker or more visible body and facial hair (hirsutism)

- Irregular or absent menstrual periods

Men with Cushing syndrome may experience:

- Decreased libido

- Decreased fertility

- Erectile dysfunction

Other signs and symptoms include:

- Severe fatigue

- Depression, anxiety and irritability

- Loss of emotional control

- Cognitive difficulties

- New or worsened high blood pressure

- Headache

- Bone loss, leading to fractures over time

- In children, impaired growth

Cushing syndrome diagnosis

Cushing’s syndrome can be hard to diagnose because it can look like other things. Your doctor may suspect Cushing’s syndrome if you have typical symptoms and are taking steroid medicine.

If you’re not taking steroids, it can be difficult to diagnose because the symptoms can be similar to other conditions.

Your doctor will talk to you, examine you and may arrange a number of tests of your blood, urine and saliva.

If Cushing’s syndrome is suspected, the amount of cortisol in your body can be measured in your:

- 24-hour urine cortisol

- Dexamethasone suppression test (low dose)

- Salivary cortisol levels (early morning and late at night).

Three tests are commonly used to diagnose Cushing syndrome. One of the most sensitive tests measures cortisol levels in the saliva between 11:00 p.m. and midnight. A sample of saliva is collected in a small plastic container and sent to the laboratory for analysis. In healthy people, cortisol levels are very low during this period of time. In contrast, people with Cushing syndrome have high levels.

Cortisol levels can also be measured in urine that has been collected over a 24-hour period.

In another screening test, people with suspected Cushing syndrome have their cortisol levels measured the morning after taking a late-night dose of dexamethasone, a laboratory-made steroid. Normally, dexamethasone causes cortisol to drop to a very low level, but in people with Cushing syndrome, this doesn’t happen.

If these tests show a high level of cortisol, you may be referred to a specialist in hormone conditions (endocrinologist) to confirm or rule out Cushing’s syndrome.

You may also need other tests or scans to find out the cause.

Other tests that may be done include any of the following:

- Fasting blood glucose and A1C to test for diabetes

- Lipid and cholesterol testing

- Bone mineral density scan to check for osteoporosis

- Blood ACTH level

- Brain MRI

- Corticotropin-releasing hormone test, which acts on the pituitary gland to cause the release of ACTH

- Dexamethasone suppression test (high dose)

- Inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) — measures ACTH levels in the veins that drain the pituitary gland compared to the veins in the chest. This test can help determine whether the cause of endogenous Cushing syndrome is rooted in the pituitary or somewhere else. For the test, blood samples are taken from the petrosal sinuses — veins that drain the pituitary glands.A thin tube is inserted into your upper thigh or groin area while you’re sedated, and threaded to the petrosal sinuses. Levels of ACTH are measured from the petrosal sinuses, and from a blood sample taken from the forearm.If ACTH is higher in the sinus sample, the problem stems from the pituitary. If the ACTH levels are similar between the sinus and forearm, the root of the problem lies outside of the pituitary gland.

How to lower cortisol

The treatment depends on the cause. Cushing’s syndrome usually gets better with treatment, although it might take a long time to recover completely. Remember to be patient. You didn’t develop Cushing syndrome overnight, and your symptoms won’t disappear overnight, either. In the meantime, these tips may help you on your journey back to health.

Treatment depends on what’s causing it.

If Cushing syndrome is caused by taking steroids:

- If you are taking steroids, then you and your doctor will need to talk about whether it is possible to reduce the dose or not. Your steroid dose will probably be gradually reduced or stopped

Exogenous Cushing syndrome goes away after a patient stops taking the cortisol-like medications they were using to treat another condition. Your doctor will determine when it is appropriate for you to slowly decrease and eventually stop using the medication.

If Cushing syndrome is caused by a tumor, treatment may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- radiotherapy to destroy the tumor

- medicines to reduce the effect of cortisol on your body

For endogenous Cushing syndrome, the initial approach is almost always surgery to remove the tumor that is causing high cortisol levels. Although surgery is usually successful, some people may also need medications that lower cortisol or radiation therapy to destroy remaining tumor cells. Some people must have both adrenal glands removed to control Cushing syndrome.

If there are other reasons as to why you have Cushing’s syndrome, then you may be advised to have treatment such as surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or other medication to stop your body taking too much cortisol.

Speak to your doctor about the benefits and risks of the different treatment options.

Cushing syndrome diet

Nutritious, wholesome foods provide a good source of fuel for your recovering body and can help you lose the extra pounds that you gained from Cushing syndrome. Make sure you’re getting enough calcium and vitamin D. Taken together, they help your body absorb calcium, which can help strengthen your bones, counteracting the bone density loss that often occurs with Cushing syndrome.

Home remedies

- Increase activities slowly. You may be in such a hurry to get your old self back that you push yourself too hard too fast, but your weakened muscles need a slower approach. Work up to a reasonable level of exercise or activity that feels comfortable without overdoing it. You’ll improve little by little, and your persistence will be rewarded.

- Monitor your mental health. Depression can be a side effect of Cushing syndrome, but it can also persist or develop after treatment begins. Don’t ignore your depression or wait it out. Seek help promptly from your doctor or a therapist if you’re depressed, overwhelmed or having difficulty coping during your recovery.

- Gently soothe aches and pains. Hot baths, massages and low-impact exercises, such as water aerobics and tai chi, can help alleviate some of the muscle and joint pain that accompanies Cushing syndrome recovery.

Coping and support

Support groups can be valuable in dealing with Cushing syndrome and recovery. They bring you together with other people who are coping with the same kinds of challenges, along with their families and friends, and offer a setting in which you can share common problems.

Ask your doctor about support groups in your community. Your local health department, public library and telephone book as well as the Internet also may be good sources to find a support group in your area.

Low cortisol levels

Decreased cortisol production may be seen with:

- An underactive pituitary gland or a pituitary gland tumor that inhibits ACTH production; this is known as secondary adrenal insufficiency.

- Underactive or damaged adrenal glands (adrenal insufficiency) that limit cortisol production; this is referred to as primary adrenal insufficiency and is also known as Addison disease.

- After stopping treatment with glucocorticosteroid hormones, especially if stopped very quickly after a long period of use

- Similar to those with adrenal insufficiency, people with a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) have low cortisol levels and do not respond to ACTH stimulation tests. Cortisol measurement is one of many tests that may be used to help evaluate a person for congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH).

- Hypothyroidism may decrease cortisol levels. Drugs that may decrease levels include some steroid hormones.

What is Addison’s disease

Addison’s disease is a rare endocrine disorder that occurs when the adrenal glands do not produce enough of their hormones – cortisol (a “stress” hormone) and aldosterone and androgens (the other hormones made by the adrenal glands) 9. Addison’s disease can be caused by damage to the adrenal glands, autoimmune conditions, and certain genetic conditions. Some of the symptoms include changes in blood pressure, chronic diarrhea, darkening of the skin, paleness, extreme weakness, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, salt craving, and weight loss. Treatment with replacement corticosteroids usually controls the symptoms.

Addison’s disease, the common term for primary adrenal insufficiency, occurs when the adrenal glands are damaged and cannot produce enough of the adrenal hormone cortisol. The adrenal hormone aldosterone and androgens may also be lacking. Addison’s disease is seen in all age groups and affects male and female equally. Addison’s disease affects 110 to 144 of every 1 million people in developed countries 10.

This disease is named after Thomas Addison, who first described patients affected by this disorder in 1855, in the book titled “On the constitutional and local effects of the disease of supra renal capsule” 11. Addison’s disease can present as a life-threatening crisis, because it is frequently unrecognized in its early stages. The basis of Addison’s disease has dramatically changed from an infectious cause to autoimmune pathology since its initial description. However, tuberculosis is still the predominant cause of Addison’s disease in developing countries 12.

Addison’s disease causes

Addison’s disease results when your adrenal glands are damaged, producing insufficient amounts of the hormone cortisol and often aldosterone as well. These glands are located just above your kidneys.

The failure of your adrenal glands to produce adrenocortical hormones is most commonly the result of the body attacking itself (autoimmune disease). An auto-immune disorder in which the body’s immune system makes antibodies which attack the cells of the adrenal cortex and slowly destroys them. This can take months to years. For unknown reasons, your immune system views the adrenal cortex as foreign, something to attack and destroy.

Other causes of adrenal gland failure may include:

- Tuberculosis. Tuberculosis was the leading cause of Addison disease up until the middle of the 20th century, when antibiotics were introduced that successfully treated tuberculosis.

- Infections (bacterial, fungal, tuberculosis) of the adrenal glands e.g. CMV virus

- Cancer that spreads to the adrenal glands

- Surgical removal of the adrenal glands

- Amyloidosis—protein build up in organs (very rare)

- Bleeding into the adrenal glands, which may present as adrenal crisis without any preceding symptoms.

Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: Addison’s Disease

The outer layer of the adrenal glands is called the adrenal cortex. If the cortex is damaged, it may not be able to produce enough cortisol.

A common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency is an autoimmune disease that causes the immune system to attack healthy tissues. In the case of Addison’s disease, the immune system turns against the adrenal gland(s). There are some very rare syndromes (several diseases that occur together) that can cause autoimmune adrenal insufficiency.

Autoimmune Disorders

Up to 80 percent of Addison’s disease cases are caused by an autoimmune disorder, which is when the body’s immune system attacks the body’s own cells and organs 13. In autoimmune Addison’s, which mainly occurs in middle-aged females, the immune system gradually destroys the adrenal cortex—the outer layer of the adrenal glands 13.

Primary adrenal insufficiency occurs when at least 90 percent of the adrenal cortex has been destroyed 10. As a result, both cortisol and aldosterone are often lacking. Sometimes only the adrenal glands are affected. Sometimes other endocrine glands are affected as well, as in polyendocrine deficiency syndrome.

Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome is a rare cause of Addison’s disease. Sometimes referred to as multiple endocrine deficiency syndrome, polyendocrine deficiency syndrome is classified into type 1 and type 2.

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1

Type 1 is inherited and occurs in children. Symptoms start during childhood. Almost any organ can be affected by autoimmune damage. Fortunately it is extremely rare—only several hundred cases have been reported worldwide. Conditions associated with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 include:

In addition to adrenal insufficiency, these children may have:

- Underactive parathyroid glands, which are four pea-sized glands located on or near the thyroid gland in the neck; they produce a hormone that helps maintain the correct balance of calcium in the body.

- Delayed or slow sexual development.

- Vitamin B12 malabsorption / deficiency (pernicious anemia), a severe type of anemia; anemia is a condition in which red blood cells are fewer than normal, which means less oxygen is carried to the body’s cells. With most types of anemia, red blood cells are smaller than normal; however, in pernicious anemia, the cells are bigger than normal.

- Candidiasis (chronic yeast infection).

- Chronic hepatitis, a liver disease.

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome Type 2

Researchers think type 2, which is sometimes called Schmidt’s syndrome, is also inherited. Type 2 usually affects young adults, symptoms primarily develop in adults aged 18 to 30 and may include:

- Addison’s disease

- Underactive or overactive thyroid function

- Delayed or slow sexual development

- Diabetes, in which a person has high blood glucose, also called high blood sugar or hyperglycemia

- White skin patches, a loss of pigment on areas of the skin (vitiligo)

- Celiac disease.

Secondary adrenal insufficiency

Adrenal insufficiency can also occur if your pituitary gland is diseased. The pituitary gland makes a hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce its hormones. Inadequate production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) can lead to insufficient production of hormones normally produced by your adrenal glands, even though your adrenal glands aren’t damaged. Doctors call this condition secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Another more common cause of secondary adrenal insufficiency occurs when people who take corticosteroids for treatment of chronic conditions, such as asthma or arthritis, abruptly stop taking the corticosteroids.

Stoppage of Corticosteroid Medication

A temporary form of secondary adrenal insufficiency may occur when a person who has been taking a synthetic glucocorticoid hormone, called a corticosteroid, for a long time stops taking the medication. Corticosteroids are often prescribed to treat inflammatory illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and ulcerative colitis. In this case, the prescription doses often cause higher levels than those normally achieved by the glucocorticoid hormones created by the body. When a person takes corticosteroids for prolonged periods, the adrenal glands produce less of their natural hormones. Once the prescription doses of corticosteroid are stopped, the adrenal glands may be slow to restart their production of the body’s glucocorticoids. To give the adrenal glands time to regain function and prevent adrenal insufficiency, prescription corticosteroid doses should be reduced gradually over a period of weeks or even months. Even with gradual reduction, the adrenal glands might not begin to function normally for some time, so a person who has recently stopped taking prescription corticosteroids should be watched carefully for symptoms of secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Surgical Removal of Pituitary Tumors

Another cause of secondary adrenal insufficiency is surgical removal of the usually noncancerous, ACTH-producing tumors of the pituitary gland that cause Cushing’s syndrome. Cushing’s syndrome is a hormonal disorder caused by prolonged exposure of the body’s tissues to high levels of the hormone cortisol. When the tumors are removed, the source of extra ACTH is suddenly gone and a replacement hormone must be taken until the body’s adrenal glands are able to resume their normal production of cortisol. The adrenal glands might not begin to function normally for some time, so a person who has had an ACTH-producing tumor removed and is going off of his or her prescription corticosteroid replacement hormone should be watched carefully for symptoms of adrenal insufficiency.

Changes in the Pituitary Gland

Less commonly, secondary adrenal insufficiency occurs when the pituitary gland either decreases in size or stops producing ACTH. These events can result from

- tumors or an infection in the pituitary

- loss of blood flow to the pituitary

- radiation for the treatment of pituitary or nearby tumors

- surgical removal of parts of the hypothalamus

- surgical removal of the pituitary

Infections

Tuberculosis (TB), an infection that can destroy the adrenal glands, accounts for 10 to 15 percent of Addison’s disease cases in developed countries.1 When primary adrenal insufficiency was first identified by Dr. Thomas Addison in 1849, TB was the most common cause of the disease. As TB treatment improved, the incidence of Addison’s disease due to TB of the adrenal glands greatly decreased. However, recent reports show an increase in Addison’s disease from infections such as TB and cytomegalovirus. Cytomegalovirus is a common virus that does not cause symptoms in healthy people; however, it does affect babies in the womb and people who have a weakened immune system—mostly due to HIV/AIDS. Other bacterial infections, such as Neisseria meningitidis, which is a cause of meningitis, and fungal infections can also lead to Addison’s disease.

Other Causes

Less common causes of Addison’s disease are:

- cancer cells in the adrenal glands

- amyloidosis, a serious, though rare, group of diseases that occurs when abnormal proteins, called amyloids, build up in the blood and are deposited in tissues and organs

- surgical removal of the adrenal glands

- bleeding into the adrenal glands

- genetic defects including abnormal adrenal gland development, an inability of the adrenal glands to respond to ACTH, or a defect in adrenal hormone production

- medication-related causes, such as from anti-fungal medications and the anesthetic etomidate, which may be used when a person undergoes an emergency

- intubation—the placement of a flexible, plastic tube through the mouth and into the trachea, or windpipe, to assist with breathing.

Low cortisol symptoms

Addison’s disease symptoms usually develop slowly, often over several months, and may include:

- Extreme fatigue, chronic, or long lasting, fatigue

- Weight loss

- Loss of appetite or decreased appetite

- Darkening of your skin (hyperpigmentation)

- Low blood pressure that drops further when a person stands up, causing dizziness or fainting

- Salt craving

- Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia)

- Nausea, diarrhea or vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Muscle or joint pains

- Muscle weakness

- Irritability

- Depression

- Body hair loss or sexual dysfunction in women

- Headache

- Sweating

- Irregular or absent menstrual periods

- In women, loss of interest in sex.

Hyperpigmentation, or darkening of the skin, can occur in Addison’s disease. This darkening is most visible on scars; skin folds; pressure points such as the elbows, knees, knuckles, and toes; lips; and mucous membranes such as the lining of the cheek.

The slowly progressing symptoms of adrenal insufficiency are often ignored until a stressful event, such as surgery, a severe injury, an illness, or pregnancy, causes them to worsen.

Figure 9. Hyperpigmentation in the hand

Figure 10. Hyperpigmentation in the mouth

Figure 11. Hyperpigmentation in the mouth

Addison’s disease treatment

All treatment for Addison’s disease involves hormone replacement therapy to correct the levels of steroid hormones your body isn’t producing.

The dose of each medication is adjusted to meet the needs of the patient.

During adrenal crisis, low blood pressure, low blood glucose, low blood sodium, and high blood levels of potassium can be life threatening. Standard therapy involves immediate IV injections of corticosteroids and large volumes of IV saline solution with dextrose, a type of sugar. This treatment usually brings rapid improvement. When the patient can take liquids and medications by mouth, the amount of corticosteroids is decreased until a dose that maintains normal hormone levels is reached. If aldosterone is deficient, the person will need to regularly take oral doses of fludrocortisone acetate.

Researchers have found that using replacement therapy for DHEA in adolescent girls who have secondary adrenal insufficiency and low levels of DHEA can improve pubic hair development and psychological stress. Further studies are needed before routine supplementation recommendations can be made.

Some options for treatment include:

- Oral corticosteroids. Hydrocortisone (Cortef), prednisone or cortisone acetate may be used to replace cortisol. Your doctor may prescribe fludrocortisone to replace aldosterone.

- Corticosteroid injections. If you’re ill with vomiting and can’t retain oral medications, injections may be needed.

Cortisol is replaced with a corticosteroid, such as hydrocortisone, prednisone, or dexamethasone, taken orally one to three times each day, depending on which medication is chosen.

If aldosterone is also deficient, it is replaced with oral doses of a mineralocorticoid hormone, called fludrocortisone acetate (Florinef), taken once or twice daily. People with secondary adrenal insufficiency normally maintain aldosterone production, so they do not require aldosterone replacement therapy.

An ample amount of sodium is recommended, especially during heavy exercise, when the weather is hot or if you have gastrointestinal upsets, such as diarrhea. Your doctor will also suggest a temporary increase in your dosage if you’re facing a stressful situation, such as an operation, an infection or a minor illness.

Addison’s disease diet

Some people with Addison’s disease who are aldosterone deficient can benefit from following a diet rich in sodium. A health care provider or a dietitian can give specific recommendations on appropriate sodium sources and daily sodium guidelines if necessary.

Corticosteroid treatment is linked to an increased risk of osteoporosis—a condition in which the bones become less dense and more likely to fracture. People who take corticosteroids should protect their bone health by consuming enough dietary calcium and vitamin D. A health care provider or a dietitian can give specific recommendations on appropriate daily calcium intake based upon age and suggest the best types of calcium supplements, if necessary.

Coping and support

These steps may help you cope better with a medical emergency if you have Addison’s disease:

- Carry a medical alert card and bracelet at all times. In the event you’re incapacitated, emergency medical personnel know what kind of care you need.

- Keep extra medication handy. Because missing even one day of therapy may be dangerous, it’s a good idea to keep a small supply of medication at work, at a vacation home and in your travel bag, in the event you forget to take your pills. Also, have your doctor prescribe a needle, syringe and injectable form of corticosteroids to have with you in case of an emergency.

- Stay in contact with your doctor. Keep an ongoing relationship with your doctor to make sure that the doses of replacement hormones are adequate, but not excessive. If you’re having persistent problems with your medications, you may need adjustments in the doses or timing of the medications.

Acute adrenal failure (Addisonian crisis)

Sudden, severe worsening of adrenal insufficiency symptoms is called adrenal crisis. If the person has Addison’s disease, this worsening can also be called an Addisonian crisis. In most cases, symptoms of adrenal insufficiency become serious enough that people seek medical treatment before an adrenal crisis occurs. However, sometimes symptoms appear for the first time during an adrenal crisis.

In acute adrenal failure (Addisonian crisis), the signs and symptoms may also include:

- Sudden, severe pain in your lower back, abdomen or legs

- Severe vomiting and diarrhea, leading to dehydration

- Low blood pressure

- Loss of consciousness

- High potassium (hyperkalemia) and low sodium (hyponatremia)

If not treated, an adrenal crisis can cause death.

Get Treatment for Adrenal Crisis Right Away – If not treated, an adrenal crisis can cause death.

Addisonian crisis requires immediate medical care. Treatment typically includes intravenous injections of:

- Hydrocortisone

- Saline solution

- Sugar (dextrose)

How is adrenal crisis treated ?

Adrenal crisis is treated with adrenal hormones. People with adrenal crisis need immediate treatment. Any delay can cause death. When people with adrenal crisis are vomiting or unconscious and cannot take their medication, the hormones can be given as an injection.

A person with adrenal insufficiency should carry a corticosteroid injection at all times and make sure that others know how and when to administer the injection, in case the person becomes unconscious.

The dose of corticosteroid needed may vary with a person’s age or size. For example, a child younger than 2 years of age can receive 25 milligrams (mg), a child between 2 and 8 years of age can receive 50 mg, and a child older than 8 years should receive the adult dose of 100 mg.

How can a person prevent adrenal crisis?

The following steps can help a person prevent adrenal crisis:

- Ask a health care provider about possibly having a shortage of adrenal hormones, if always feeling tired, weak, or losing weight.

- Learn how to increase the dose of corticosteroid for adrenal insufficiency when ill. Ask a health care provider for written instructions for sick days. First discuss the decision to increase the dose with the health care provider when ill.

- When very ill, especially if vomiting and not able to take pills, seek emergency medical care immediately.

How can someone with adrenal insufficiency prepare in case of an emergency?

People with adrenal insufficiency should always carry identification stating their condition, “adrenal insufficiency,” in case of an emergency. A card or medical alert tag should notify emergency health care providers of the need to inject corticosteroids if the person is found severely injured or unable to answer questions.

The card or tag should also include the name and telephone number of the person’s health care provider and the name and telephone number of a friend or family member to be notified. People with adrenal insufficiency should always carry a needle, a syringe, and an injectable form of corticosteroids for emergencies.

References- Modified-release hydrocortisone to provide circadian cortisol profiles. Debono M, Ghobadi C, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Huatan H, Campbell MJ, Newell-Price J, Darzy K, Merke DP, Arlt W, Ross RJ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 May; 94(5):1548-54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2684472/

- Twenty-four hour pattern of the episodic secretion of cortisol in normal subjects. Weitzman ED, Fukushima D, Nogeire C, Roffwarg H, Gallagher TF, Hellman L. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971 Jul; 33(1):14-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4326799/

- Estimation of daily cortisol production and clearance rates in normal pubertal males by deconvolution analysis. Kerrigan JR, Veldhuis JD, Leyo SA, Iranmanesh A, Rogol AD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993 Jun; 76(6):1505-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8501158/

- Glucocorticoid replacement therapy: are patients over treated and does it matter? Peacey SR, Guo CY, Robinson AM, Price A, Giles MA, Eastell R, Weetman AP. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997 Mar; 46(3):255-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9156031/

- The circadian rhythm of glucocorticoids is regulated by a gating mechanism residing in the adrenal cortical clock. Oster H, Damerow S, Kiessling S, Jakubcakova V, Abraham D, Tian J, Hoffmann MW, Eichele G. Cell Metab. 2006 Aug; 4(2):163-73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16890544/

- Splanchnicotomy increases adrenal sensitivity to ACTH in nonstressed rats. Jasper MS, Engeland WC. Am J Physiol. 1997 Aug; 273(2 Pt 1):E363-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9277390/

- Transcriptional profiling in the adrenal gland reveals circadian regulation of hormone biosynthesis genes and nucleosome assembly genes. Oster H, Damerow S, Hut RA, Eichele G. J Biol Rhythms. 2006 Oct; 21(5):350-61.

- Diurnal rhythmicity of the canonical clock genes Per1, Per2 and Bmal1 in the rat adrenal gland is unaltered after hypophysectomy. Fahrenkrug J, Hannibal J, Georg B. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008 Mar; 20(3):323-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18208549/

- Adrenal Insufficiency. https://www.hormone.org/diseases-and-conditions/adrenal/adrenal-insufficiency

- Betterle C, Morlin L. Autoimmune Addison’s disease. In: Ghizzoni L, Cappa M, Chrousos G, Loche S, Maghnie M, eds. Pediatric Adrenal Diseases. Endocrine Development. Vol. 20. Padova, Italy: Karger Publishers; 2011: 161–172.

- The conquest of Addison’s disease. Hiatt JR, Hiatt N. Am J Surg. 1997 Sep; 174(3):280-3.

- Stewart PM, Krone NP. The adrenal cortex. In: Kronenburg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Reed Larson P, editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. pp. 515–20. Ch. 15.

- Neary N, Nieman L. Adrenal insufficiency: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2010;(3):217–223.