Chylous ascites

Chylous ascites also known as chyloperitoneum, is a rare form of ascites caused by accumulation of milky lymphatic fluid with a triglyceride level >110 mg/dL in the peritoneal cavity and is caused by disruption of the lymphatic system from any cause 1. Chylous ascites is usually due to intra-abdominal malignancy, liver cirrhosis or abdominal surgery complications, and present with painless but progressive abdominal distension, dyspnea and weight gain 2.

Chylous ascites causes

Chylous ascites is an uncommon clinical condition that occurs as a result of disruption of the abdominal lymphatics. Chylous ascites may be divided into traumatic and atraumatic causes (Table 1). Multiple causes have been described, with the most common causes being abdominal malignancy (hepatoma, small bowel lymphoma, small bowel angiosarcoma, and retroperitoneal lymphoma), cirrhosis (≤0.5% of patients with ascites from cirrhosis may have chylous ascites), and trauma after abdominal surgery 3 in developed countries and account for over two-thirds of all cases, whereas chronic infections like tuberculosis and filariasis account for the majority of the cases in developing countries 4.

Other causes include the following:

- Blunt abdominal trauma

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- Pelvic irradiation

- Peritoneal dialysis

- Abdominal tuberculosis

- Carcinoid syndrome

- Congenital defects of lacteal formation

Table 1. Etiological classification of chylous ascites

| Atraumatic | Traumatic | |

|---|---|---|

| (I) Neoplastic | Cardiac | (I) Iatrogenic |

| Solid organ cancers | Constrictive pericarditis | (A) Surgical |

| Lymphoma | Congestive heart failure | Abdominal aneurysm repair |

| Sarcoma | Gastrointestinal | Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy |

| Carcinoid tumors | Celiac sprue | Placement of peritoneal dialysis catheter |

| Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | Whipple’s disease | Inferior vena cava resection |

| Chronic lymphatic leukemia | Intestinal malrotation | Pancreaticoduodenectomy |

| (II) Diseases | Small bowel volvulus | Vagotomy |

| (A) Congenital | Ménétrier disease | Radical and laparoscopic nephrectomy |

| Primary lymphatic hypoplasia | Inflammatory | Nissen fundoplication |

| Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome | Pancreatitis | Distal splenorenal shunts |

| Yellow nail syndrome | Fibrosing mesenteritis | Laparoscopic adrenalectomy |

| Primary lymphatic hyperplasia | Retroperitoneal fibrosis | Gynecological surgery |

| Lymphangioma | Sarcoidosis | (B) Nonsurgical |

| Familial visceral myopathy | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Radiotherapy |

| (B) Acquired | Behçet’s disease | (II) Noniatrogenic |

| Cirrhosis | Peritoneal dialysis | Blunt abdominal trauma |

| Infectious | Hyperthyroidism | Battered child syndrome |

| Tuberculosis | Nephrotic syndrome | Penetrating abdominal trauma |

| Filariasis | Drugs | Shear forces to the root of the mesentery |

| Mycobacterium avium in AIDS | Calcium channel blockers | (III) Idiopathic |

| Ascariasis | Sirolimus | Rule out lymphoma |

In adults, chylous ascites is associated most frequently with malignant conditions. These conditions particularly include lymphomas and disseminated carcinomas from primary neoplasms in the pancreas, breast, colon, prostate, ovary, testes, and kidney. Infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis 6 and filariasis 7 can cause chylous ascites. Chylous ascites has also been reported in adults in association with hepatoma, small bowel angiosarcoma, retroperitoneal lymphoma, jejunal carcinoid 8 and sclerosing mesenteritis 9.

In children, the most common causes of chylous ascites are congenital abnormalities, such as lymphangiectasia, mesenteric cyst, and idiopathic “leaky lymphatics.” Other congenital causes include primary lymphatic hypoplasia associated with Turner syndrome and yellow nail syndrome, and the lymphatic malformations associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome 10. Lymphatics may spontaneously rupture in patients with cirrhosis as a result of higher than typical flow, with the formation of chylous ascites. Chylous ascites has been reported in patients with polycythemia vera and resulting hepatic vein thrombosis.

Abdominal surgery is a common cause of chylous ascites. The most frequently associated surgical procedures are resection of abdominal aortic aneurysm and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. In a series of 329 patients with testicular cancer who underwent postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, 7% of patients developed chylous ascites 11. Chylous ascites has also been described after several abdominal procedures, such as peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion 12, pancreatic resection 13, splenorenal shunt surgery 14, cadaveric 15 and living donor liver transplantation 16, laparoscopic donor nephrectomy 17 and laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication.

Chylous ascites pathophysiology

The principal mechanisms for chylous ascites formation are related to disruption of the lymphatic system, from any cause. Three basic mechanisms have been proposed using lymphangiography and inspection at laparotomy 18:

- Exudation of lymph through the walls of retroperitoneal megalymphatics into the peritoneal cavity, which occurs with or without a visible fistula (i.e., congenital lymphangiectasia),

- Leakage of lymph from the dilated subserosal lymphatics on the bowel wall into the peritoneal cavity which is due to malignant infiltration of the lymph nodes obstructing the flow of lymph from the gut to the cisterna chili,

- Direct leakage of lymph through a lymphoperitoneal fistula associated with retroperitoneal megalymphatics due to acquired lymphatic disruption as a result of trauma or surgery.

In addition, the increased caval and hepatic venous pressures caused by constrictive pericarditis, right-sided heart failure, and dilated cardiomyopathy may precipitate chylous ascites through large increase in production of hepatic lymph 19. Finally, cirrhosis also causes an increased formation of hepatic lymph 20. In fact, decompression of the portal vein in patients with portal hypertension has been shown to relieve lymphatic hypertension 21.

Chylous ascites symptoms

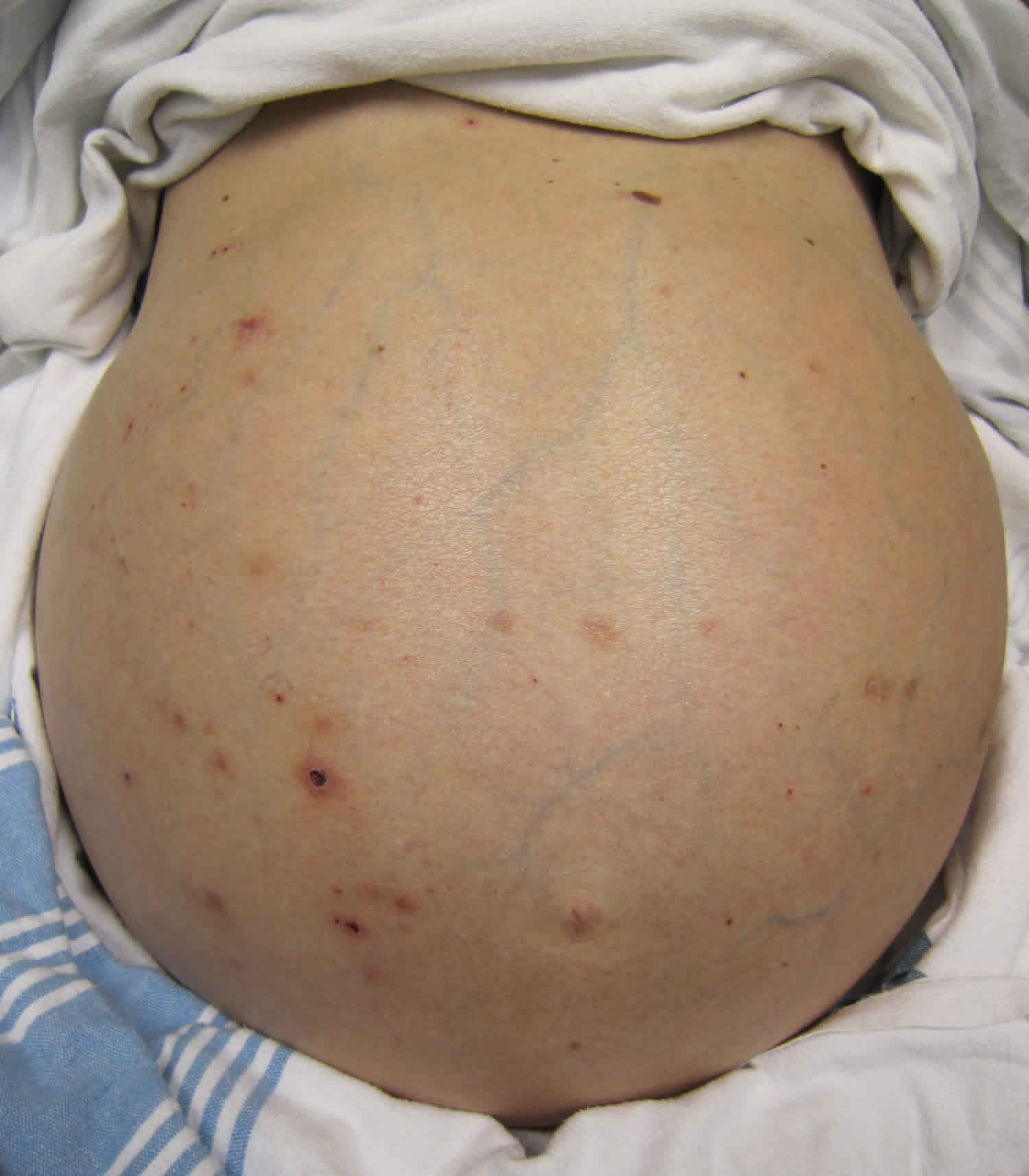

Abdominal distention is the most common symptom in patients with chylous ascites. Other clinical features include abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss/gain, edema, weakness, nausea, dyspnea, lymphadenopathy, early satiety, fever, and night sweats. Fever, night sweats, and lymphadenopathy are usually observed in patients with lymphoma. Often, features of the primary illness, such as cirrhosis or of an associated malignancy, dominate the clinical picture. Rarely, it can present as acute peritonitis 22 or as a consequence of acute gallstone pancreatitis 23.

Chylous ascites clinical presentation:

- abdominal distension

- abdominal discomfort

- dyspnea: splinting of the diaphragm by ascites

- sequelae of hypoproteinemia: edema

- acute abdomen: acute chylous peritonitis 7

For fluid aspirated from the abdomen to be chyle, triglycerides need to be elevated above 110 mg/dL (two to eightfold more than normal plasma concentration) with a specific gravity >1.012.

Chylous ascites complications

Sepsis is the most common complication, and sudden death has been reported in patients with chylous ascites.

Loss of chyle into peritoneal cavity can lead to serious consequences because of the loss of essential proteins, lipids, immunoglobulins, vitamins, electrolytes, and water. While repeated therapeutic paracentesis provides relief from symptoms, the nutritional deficiency will continue to persist or deteriorate unless definitive therapeutic measures are instituted to stop leakage of chyle into the peritoneal space. In fact, in postoperative settings, this may cause increased mortality 24. Therefore, it is very important to provide adequate nutritional support replenishing fluid loss, vitamin deficiencies, and electrolyte loss while specific therapeutic measures are planned.

In addition, continued loss of lymphocyte-rich lymph into the peritoneal space and enormous loss of protein in gastrointestinal tract lead to hypogammaglobulinemia and therefore increased susceptibility to infection 25. Prolonged thoracic duct drainage has been used previously to induce immunosuppression in several diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and myasthenia gravis 25.

The bioavailability of certain drugs could be drastically impaired in the presence of significant chyle leak. There are reports of this phenomenon in patients with chylothorax-causing subtherapeutic digoxin 26, amiodarone 27 and cyclosporine 28 levels in the serum. Sequestration of drugs in chyle should be recognized early, to prevent subtherapeutic plasma levels in patients undergoing drainage of chylous ascites.

Chylous ascites diagnosis

The diagnostic approach of chylous ascites consists of first suspecting the diagnosis, then confirming the presence of chyle in the peritoneal cavity, and finally determining the underlying abnormality. A careful history, physical examination, and diagnostic paracentesis are the key in the initial evaluation of any patient presenting with ascites.

Abdominal paracentesis is the most important diagnostic tool in evaluating and managing patients with ascites. In contrast to the yellow and transparent appearance of ascites due to cirrhosis and portal hypertension, chyle typically has a cloudy and turbid appearance (see Table 2 below). This should be distinguished from pseudochylous ascites, in which the turbid appearance is due to cellular degeneration from infection or malignancy without actually containing high levels of triglycerides 29. Depending on the clinical suspicion, ascitic fluid should be sent for cell count, culture, Gram stain, total protein, albumin, triglyceride levels, glucose, lactate dehydrogenase, amylase, and cytology 30. The serum to ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) should be calculated to determine if the ascites is related to portal hypertension or other causes 30. The triglyceride levels in ascitic fluid are very important in defining chylous ascites. Triglyceride values are typically above 200 mg/dL, although some authors use a cutoff value of 110 mg/dL 31. A tuberculosis smear and culture and adenosine deaminase activity should be performed in selected cases when tuberculosis is suspected 31. Adenosine deaminase activity has high sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis 32. In contrast, its utility in populations with high prevalence of cirrhosis such as the United States is limited 33. The diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis usually requires a peritoneal biopsy via laparoscopy 34.

Laboratory studies

Routine laboratory tests may show hypoalbuminemia, lymphocytopenia, anemia, hyperuricemia, elevated levels of alkaline phosphatase and liver enzymes, and hyponatremia. Serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels are usually normal.

Abnormal liver enzyme levels are more common in patients with disseminated carcinoma than in patients with lymphoma or nonmalignant disorders. Anemia is common in patients with neoplasia.

The diagnosis of chylous ascites is made by peritoneocentesis and by analysis of the ascitic fluid. An ascitic triglyceride concentration above 200 mg/dL is consistent with chylous ascites 3.

Ascitic fluid study

Ascitic fluid is usually white or milky. Gross milkiness of the ascitic fluid corresponds poorly with absolute triglyceride levels, because turbidity also reflects the size of the chylomicrons.

The ascites triglyceride level is elevated in all patients. Typically, chylous ascites is diagnosed when the ascites triglyceride level is greater than 110 mg/dL. Levels as high as 8100 mg/dL have been described 35. Other authors have identified an elevated ascites-to-plasma triglyceride ratio (between 2:1 and 8:1) as being indicative of chylous ascites 7.

Table 2. Characteristics of ascitic fluids in chylous ascites

| Color | Milky and cloudy |

|---|---|

| Triglyceride level | Above 200 mg/dL |

| Cell count | Above 500 (lymphocytic predominance) |

| Total protein | Between 2.5 and 7.0 g/dL |

| Serum-ascites albumin gradient | Below 1.1 g/dL (is elevated above 1.1 g/dL in chylous ascites secondary to cirrhosis) |

| Cholesterol | Low (ascites/serum ratio < 1) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | Between 110 and 200 IU/L |

| Culture | Positive in selected cases of tuberculosis |

| Cytology | Positive in malignancy |

| Amylase | Elevated in cases of pancreatitis |

| Glucose | Below 100 mg/dL |

Other ascites tests include the following 35:

- The specific gravity is 1.010-1.054.

- Total fat content is 4-40 g/L.

- Glucose and amylase levels are usually normal.

- Cholesterol level is usually low.

- The leukocyte count is generally high (232-2560 cells/mm3), usually with a marked lymphocytic predominance.

- The total protein content varies from 1.4 to 6.4 g/dL, with a mean of 3.7 g/dL. This variation reflects changes in serum proteins and dietary habits.

- Microbiologic cultures are usually negative

Other diagnostic tests

Other studies may be indicated, such as the following:

- Computed tomography (CT) scanning

- Lymph node biopsy

- Laparascopy

- Laparotomy

- Lymphangiography

- Bone marrow examination

- Intravenous pyelography

CT scanning, lymph node biopsy, and laparotomy carry the highest yield of diagnostic information. The role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not well defined. Note that lymphangiography can transiently worsen chylous ascites due to the oily contrast medium used for the test.

Chylous ascites treatment

Because chylous ascites is a manifestation rather than a disease by itself, the treatment depends on the underlying disease or cause 3.

Supportive measures can relieve the symptoms. These measures include repeated paracentesis, diuretic therapy, salt and water restriction, elevation of the legs and the use of supportive stockings, and dietary measures.

Lymphatic flow increases after the ingestion of a fatty meal. The fatty acids derived from short-chain and medium-chain triglycerides diffuse directly across enterocytes into the portal venous system. Their absorption does not affect lymphatic flow. However, the fatty acids derived from long-chain triglycerides are re-esterified into triglycerides in the enterocyte. They are then incorporated into chylomicrons which subsequently enter the lymphatic system.

A low-fat diet with medium-chain triglyceride supplementation can reduce the flow of chyle into the lymphatics 36. Typically, medium-chain triglyceride oil is administered orally at a dose of 15 mL three times per day with meals. However, this approach is frequently not successful. One case report described the successful use of orlistat (Xenical) in a patient who had difficulty complying with a low-fat diet 37.

If chylous ascites persists despite dietary management, the next step may involve bowel rest and the institution of total parenteral nutrition 38. Bowel rest and total parenteral nutrition are postulated to be beneficial in patients with posttraumatic or postsurgical chylous ascites.

Paracentesis can result in immediate symptom relief; however, reaccumulation of fluid usually follows, and patients may require repeated paracentesis. Some authorities have advocated large-volume paracentesis. Morbidity from a single tap is usually low, but complications (eg, peritonitis, hemorrhage) can occur. Transfusion of albumin and/or red blood cells (RBCs) during paracentesis may help prevent hypovolemia in patients with hypoalbuminemia or anemia.

Multiple case reports describe the use of octreotide, a somatostatin analogue, in the management of chylous ascites, typically at a dose of 100 mcg administered subcutaneously three times per day 39. A combination of total parenteral nutrition and subcutaneous octreotide has been used successfully to treat congenital chylous ascites in a newborn 40. Experimental work in humans has shown that somatostatin can significantly decrease postprandial increases in triglyceride levels. This effect cannot be explained by either inhibition of gastric emptying or inhibition of exocrine pancreatic secretion 41. Octreotide is most likely effective in chylous ascites owing to its ability to inhibit lymphatic flow. Indeed, in a canine model, infusion of somatostatin resulted in a decrease in lymph flow, measured via a cannula inserted into the thoracic duct 42.

A 2017 case report noted the addition of octreotide to sirolimus therapy reduced chylous effusion in a woman with lymphangioleimyomatosis who developed refractory chylothorax and chylous ascites during sirolimus therapy 43.

Postsurgical chylous ascites usually resolves with supportive therapy. Early reoperation is indicated when the site of leakage is apparent and if the patient is a good operative candidate 44. Case reports have described the laparoscopic treatment of chylous leaks, using suture ligation and fibrin glue to control the leak 45. In a separate report, fibrin glue applied to absorbable mesh was useful in patients with large areas of diffuse lymphatic leakage 46. Another report described the treatment of chylous ascites after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with percutaneous injection of tissue glue (ie, N -butyl-cyanoacrylate mixed with ethiodol) into the thoracic duct 47.

Lymphangiography itself may play more than a diagnostic role in the management of lymphatic leaks 48. Lymphangiography with lipiodol led to the resolution of lymphatic leakage in a small number of patients with postoperative chylous ascites 49. Lipiodol has been used as an embolic agent in a variety of angiographic procedures. Furthermore, it has been postulated that leakage of lipiodol from the site of lymphatic vessel perforation may stimulate a local inflammatory reaction in the surrounding soft tissues. This, in turn, may lead to the closure of the leaks 50.

The combination of lymphangiography and lymphatic embolization appears to be effective in the treatment of refractory chylous ascites. In a retrospective study of 31 patients with refractory chylous ascites, the investigators visualized the lymphatic leak in 17 (55%) of the 31 patients who underwent conventional lymphangiography and in 7 (78%) of 9 patients who underwent magnetic resonance lymphangiography. Eleven of the 17 patients whose leak was identified underwent embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue and/or coils, with 9 patients (82%) achieving resolution of the chylous ascites. There was a 52% overall rate of ascites resolution, with greater success when the leak site was identified 51.

Similar results were noted in a retrospective study (2016-2017) of three patients with previously unidentifiable leakage site or failed lymphatic embolization who underwent endolymphatic balloon-occluded retrograde abdominal lymphangiography (BORAL) and embolization (BORALE) for the diagnosis and treatment of chylous ascites 52. Technical success with pelvic lymphangiography and BORAL was achieved in all three patients, and BORAL was technically successful in the two patients it was attempted in. Resolution of the chylous ascites occurred in all the patients, with no minor/major complications reported 52. More investigation is needed.

Peritoneovenous shunting has been used successfully in small numbers of patients with chylous ascites 53. However, shunt failure is common and the procedure may be fraught with complications.

Use of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) to successfully treat chylous ascites related to cirrhosis has been reported 54.

Malignant chylous ascites requires specific therapy directed at the primary cause as well as supportive therapy. These therapies may include chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. Laparotomy and ligation of the leaking lymphatics, resection of a leaking small bowel segment, and removal of an obstructing tumor all have been attempted with varying degrees of success. Transient success also has been achieved with peritoneovenous shunts.

Laparotomy should not be used in pediatric patients with chylous ascites unless the condition is unresponsive to conservative therapy and a lesion that can be corrected by surgery is apparent.

Chylous ascites prognosis

The prognosis in adult patients with chylous ascites is poor due to its association with malignancy and severe liver disease. However, pediatric patients and adult patients with postsurgical and posttraumatic chylous ascites have a favorable prognosis.

References- Tsai MK, Lai CH, Chen LM, Jong GP. Calcium Channel Blocker-Related Chylous Ascites: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(4):466. Published 2019 Apr 5. doi:10.3390/jcm8040466 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6518248

- Basualdo J.E., Rosado I.A., Morales M.I., Fernández-Ros N., Huerta A., Alegre F., Landecho M.F., Lucena J.F. Lercanidipine-induced chylous ascites: Case report and literature review. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2017;42:638–641. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12555

- Lizaola B, Bonder A, Trivedi HD, Tapper EB, Cardenas A. Review article: the diagnostic approach and current management of chylous ascites. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Nov. 46(9):816-24.

- Al-Busafi SA, Ghali P, Deschênes M, Wong P. Chylous Ascites: Evaluation and Management. ISRN Hepatol. 2014;2014:240473. Published 2014 Feb 3. doi:10.1155/2014/240473 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4890871

- Sathiravikarn W, Apisarnthanarak A, Apisarnthanarak P, Bailey TC. Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated chylous ascites in HIV-infected patients: case report and review of the literature. Infection. 2006 Aug. 34(4):230-3.

- Aalami OO, Allen DB, Organ CH Jr. Chylous ascites: a collective review. Surgery. 2000 Nov. 128(5):761-78.

- Ayers R. Chylous ascites and jejunal carcinoid: a diagnostic challenge. ANZ J Surg. 2005 Jul. 75(7):618-9.

- Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA, Smyrk TC. Sclerosing mesenteritis: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in ninety-two patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 May. 5(5):589-96; quiz 523-4.

- )Aalami OO, Allen DB, Organ CH Jr. Chylous ascites: a collective review. Surgery. 2000 Nov. 128(5):761-78.). Neoplasia is an uncommon cause of pediatric chylous ascites.

The incidence of spontaneous chylous ascites in patients with chronic liver diseases is estimated to be 0.5%. Fluid in the space of Disse may enter the lymphatic channels in the portal and central venous areas of the liver. An increase in portal pressure can lead to increased flow of fluid into both the space of Disse and the liver’s lymphatic system. Indeed, patients with cirrhosis have increased thoracic duct lymph flow ((Witte MH, Witte CL, Dumont AE. Progress in liver disease: physiological factors involved in the causation of cirrhotic ascites. Gastroenterology. 1971 Nov. 61(5):742-50.

- Evans JG, Spiess PE, Kamat AM, et al. Chylous ascites after post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection: review of the M. D. Anderson experience. J Urol. 2006 Oct. 176(4 Pt 1):1463-7.

- Cheung CK, Khwaja A. Chylous ascites: an unusual complication of peritoneal dialysis. A case report and literature review. Perit Dial Int. 2008 May-Jun. 28(3):229-31.

- Assumpcao L, Cameron JL, Wolfgang CL, et al. Incidence and management of chyle leaks following pancreatic resection: a high volume single-center institutional experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 Nov. 12(11):1915-23.

- Edoute Y, Nagachandran P, Assalia A, Ben-Ami H. Transient chylous ascites following a distal splenorenal shunt. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000 Mar-Apr. 47(32):531-2.

- Yilmaz M, Akbulut S, Isik B, et al. Chylous ascites after liver transplantation: incidence and risk factors. Liver Transpl. 2012 Sep. 18(9):1046-52.

- Baran M, Cakir M, Yuksekkaya HA, et al. Chylous ascites after living related liver transplantation treated with somatostatin analog and parenteral nutrition. Transplant Proc. 2008 Jan-Feb. 40(1):320-1.

- Aerts J, Matas A, Sutherland D, Kandaswamy R. Chylous ascites requiring surgical intervention after donor nephrectomy: case series and single center experience. Am J Transplant. 2010 Jan. 10(1):124-8.

- Browse N. L., Wilson N. M., Russo F., Al-Hassan H., Allen D. R. Aetiology and treatment of chylous ascites. British Journal of Surgery. 1992;79(11):1145–1150. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800791110

- Güneri S., Nazli C., Kinay O., Kirimli O., Mermut C., Hazan E. Chylous ascites due to constrictive pericarditis. International Journal of Cardiac Imaging. 2000;16(1):49–54. doi: 10.1023/A:1006379625554

- Maywood B. T., Goldstein L., Busuttil R. W. Chylous ascites after a Warren shunt. American Journal of Surgery. 1978;135(5):700–702.

- Cheng W. S. C., Gough I. R., Ward M., Croese J., Powell L. W. Chylous ascites in cirrhosis: a case report and review of literature. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 1989;4(1):95–99.

- Smith EK, Ek E, Croagh D, Spain LA, Farrell S. Acute chylous ascites mimicking acute appendicitis in a patient with pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Oct 14. 15(38):4849-52.

- Poo S, Pencavel TD, Jackson J, Jiao LR. Portal hypertension and chylous ascites complicating acute pancreatitis: the therapeutic value of portal vein stenting. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018 Jan. 100(1):e1-e3.

- Gaglio P. J., Leevy C. B., Koneru B. Peri-operative chylous ascites. Journal of Medicine. 1996;27(5-6):369–376.

- Camiel M. R., Benninghoff D. L., Alexander L. L. Chylous effusions, extravasation of lymphographic contrast material, hypoplasia of lymph nodes and lymphocytopenia. Chest. 1971;59(1):107–110.

- Taylor M. D., Kim S. S., Vaias L. J. Therapeutic digoxin level in chylous drainage with no detectable plasma digoxin level. Chest. 1998;114(5):1482–1484.

- Strange C., Nicolau D. P., Dryzer S. R. Chylous transport of amiodarone. Chest. 1992;101(2):573–574.

- Repp R., Scheld H. H., Bauer J., Becker H., Kreuder J., Netz H. Cyclosporine losses by a chylothorax. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 1992;11(2):397–398.

- Runyon B. A., Akriviadis E. A., Keyser A. J. The opacity of portal hypertension-related ascites correlates with the fluid’s triglyceride concentration. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1991;96(1):142–143.

- Runyon B. A. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49(6):2087–2107. doi: 10.1002/hep.22853

- Cárdenas A., Chopra S. Chylous ascites. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2002;97(8):1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9270(02)04268-5

- Riquelme A., Calvo M., Salech F., et al. Value of adenosine deaminase (ADA) in ascitic fluid for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2006;40(8):705–710. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00009

- Hillebrand D. J., Runyon B. A., Yasmineh W. G., Rynders G. P. Ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase insensitivity in detecting tuberculous peritonitis in the United States. Hepatology. 1996;24(6):1408–1412. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008938171

- Martinez-Vazquez J. M., Ocana I., Ribera E., Segura R. M., Pascual C. Adenosine deaminase activity in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. Gut. 1986;27(9):1049–1053.

- Press OW, Press NO, Kaufman SD. Evaluation and management of chylous ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1982 Mar. 96(3):358-64.

- Weinstein LD, Scanlon GT, Hersh T. Chylous ascites. Management with medium-chain triglycerides and exacerbation by lymphangiography. Am J Dig Dis. 1969 Jul. 14(7):500-9.

- Chen J, Lin RK, Hassanein T. Use of orlistat (xenical) to treat chylous ascites. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005 Oct. 39(9):831-3.

- Ijichi H, Soejima Y, Taketomi A, et al. Successful management of chylous ascites after living donor liver transplantation with somatostatin. Liver Int. 2008 Jan. 28(1):143-5.

- Zhou DX, Zhou HB, Wang Q, Zou SS, Wang H, Hu HP. The effectiveness of the treatment of octreotide on chylous ascites after liver cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009 Aug. 54(8):1783-8.

- Olivieri C, Nanni L, Masini L, Pintus C. Successful management of congenital chylous ascites with early octreotide and total parenteral nutrition in a newborn. BMJ Case Rep. 2012 Sep 25; 2012.

- Hengl G, Prager J, Mörz R, Pointner H, Deutsch E. [Further examinations of the influence of somatostatin on triglyceride absorption (author’s transl)] [German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1980 Jan 30. 130(2):49-52.

- Nakabayashi H, Sagara H, Usukura N, et al. Effect of somatostatin on the flow rate and triglyceride levels of thoracic duct lymph in normal and vagotomized dogs. Diabetes. 1981 May. 30(5):440-5.

- Namba M, Masuda T, Nakamura T, et al. Additional octreotide therapy to sirolimus achieved a decrease in sirolimus-refractory chylous effusion complicated with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Intern Med. 2017 Dec 15. 56(24):3327-31.

- Ablan CJ, Littooy FN, Freeark RJ. Postoperative chylous ascites: diagnosis and treatment. A series report and literature review. Arch Surg. 1990 Feb. 125(2):270-3.

- Jensen EH, Weiss CA 3rd. Management of chylous ascites after laparoscopic cholecystectomy using minimally invasive techniques: a case report and literature review. Am Surg. 2006 Jan. 72(1):60-3.

- Zeidan S, Delarue A, Rome A, Roquelaure B. Fibrin glue application in the management of refractory chylous ascites in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008 Apr. 46(4):478-81.

- Hwang PF, Ospina KA, Lee EH, Rehring SR. Unconventional management of chyloascites after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. JSLS. 2012 Apr-Jun. 16(2):301-5.

- Kim J, Won JH. Percutaneous treatment of chylous ascites. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016 Dec. 19(4):291-8.

- Matsumoto T, Yamagami T, Kato T, et al. The effectiveness of lymphangiography as a treatment method for various chyle leakages. Br J Radiol. 2009 Apr. 82(976):286-90.

- Yamagami T, Masunami T, Kato T, et al. Spontaneous healing of chyle leakage after lymphangiography. Br J Radiol. 2005 Sep. 78(933):854-7.

- Nadolski GJ, Chauhan NR, Itkin M. Lymphangiography and lymphatic embolization for the treatment of refractory chylous ascites. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017 Dec 13.

- Srinivasa RN, Gemmete JJ, Osher ML, Hage AN, Chick JFB. Endolymphatic Balloon-Occluded Retrograde Abdominal Lymphangiography (BORAL) and Embolization (BORALE) for the diagnosis and treatment of chylous ascites: approach, technical success, and clinical outcomes. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017 Dec 5.

- Matsufuji H, Nishio T, Hosoya R. Successful treatment for intractable chylous ascites in a child using a peritoneovenous shunt. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006 May. 22(5):471-3.

- Kikolski SG, Aryafar H, Rose SC, Roberts AC, Kinney TB. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for treatment of cirrhosis-related chylothorax and chylous ascites: single-institution retrospective experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013 Aug. 36(4):992-7.