Commotio cordis

Commotio cordis is ventricular fibrillation precipitated by blunt trauma to the heart, not attributable to structural damage to the heart or surrounding structures 1. Ventricular fibrillation is a heart rhythm problem that occurs when the heart beats with rapid, erratic electrical impulses. This causes pumping chambers in your heart (the ventricles) to quiver uselessly, instead of pumping blood. Ventricular fibrillation, an emergency that requires immediate medical attention, causes the person to collapse within seconds. It is the most frequent cause of sudden cardiac death. Emergency treatment includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and shocks to the heart with a device called an automated external defibrillator (AED).

Commotio cordis is a rare cause of sudden cardiac death that can occur in anyone, as the result of a blunt blow to the chest, such as being hit by a hockey puck, a baseball or another player. The blow to the chest can trigger ventricular fibrillation if the blow strikes at exactly the wrong time in the heart’s electrical cycle. Most commotio cordis cases currently reported involve young athletes playing sports. Although commotio cordis usually involves impact from a baseball, it has also been reported during hockey, softball, lacrosse, karate, and other sports activities in which a relatively hard and compact projectile or bodily contact caused impact to the person’s precordium (region of the thorax immediately in front of or over the heart). According to the latest reported data from US Commotio Cordis Registry, at the time of the incident, 53% of persons struck were engaged in organized competitive athletics. The remainder were involved in normal daily activities (23%) or recreational sports (24%).

The rate of successful resuscitation remains relatively low but is improving slowly 2. The reported survival rate among African Americans is lower than in whites (4% vs. 33%). This may be a result of a higher rate of delayed resuscitation (44% vs. 22%) and less frequent use of automated external defibrillators (4% vs. 8%) 3. Survival has usually been associated with effective and timely CPR efforts and defibrillation that occur within 3 minutes of the collapse. The survival rate is only 5% or less in cases in which resuscitative efforts were delayed longer than 3 minutes. Although numerous individuals have been resuscitated with the restoration of a perfusing heart rhythm, many of these individuals have experienced irreversible ischemic encephalopathy and ultimately died as a result of the injury.

One would expect survival to be similar to other cases of ventricular fibrillation, if not even higher because of the lack of structural heart disease. While initial cases reported very low survival, a significant increase in reported survival has been noted in recent years, likely due to improved recognition and early treatment 3. The most recently reported survival rates exceed 50%.

While only 216 instances have been reported to the US Commotio Cordis Registry (as of 2012) 4, this is probably a considerable underestimation of its true incidence since this entity still goes unrecognized in many instances and continues to be underreported. Reported cases remain relatively infrequent (less than 30 cases are reported each year).

Children appear to be at the highest risk for commotio cordis 5. The mean age reported in the US Commotio Cordis Registry is 15 years, and very few cases have been reported above 20 years old. This may be a result of a combination of a thinner chest wall relative to an adult, and an increased likelihood to participate in activities where they are likely to be hit in the chest.

Ninety-five percent of reported cases occur in boys, which is likely again a reflection of selection for participation in sports which provide the risk factors necessary for commotio cordis to occur. However, the anatomical differences in the chest wall thickness may also play a role.

If you or someone else is having commotio cordis, seek emergency medical help immediately. Follow these steps:

- Call your local emergency number.

- If the person is unconscious, check for a pulse.

- If no pulse, begin CPR to help maintain blood flow to the organs until an electrical shock (defibrillation) can be given. Push hard and fast on the person’s chest — about 100 compressions a minute. It’s not necessary to check the person’s airway or deliver rescue breaths unless you’ve been trained in CPR.

Portable automated external defibrillators, which can deliver an electrical shock that may restart heartbeats, are available in an increasing number of places, such as in airplanes, police cars and shopping malls. They can even be purchased for your home.

Portable defibrillators come with built-in instructions for their use. They’re programmed to deliver a shock only when it’s needed.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation steps

Before you starting cardiopulmonary resuscitation, check:

- Is the environment safe for the person?

- Is the person conscious or unconscious?

- If the person appears unconscious, tap or shake his or her shoulder and ask loudly, “Are you OK?”

- If the person doesn’t respond and two people are available, have one person call 911 or the local emergency number and get the automated external defibrillator (AED), if one is available, and have the other person begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

- If you are alone and have immediate access to a telephone, call your local emergency number before beginning cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Get the automated external defibrillator (AED), if one is available.

- As soon as an automated external defibrillator (AED) is available, deliver one shock if instructed by the device, then begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Remember to spell C-A-B (compressions, airway, breathing)

The American Heart Association uses the letters C-A-B (compressions, airway, breathing) — to help people remember the order to perform the steps of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Compressions: Restore blood circulation

- Put the person on his or her back on a firm surface.

- Kneel next to the person’s neck and shoulders.

- Place the heel of one hand over the center of the person’s chest, between the nipples. Place your other hand on top of the first hand. Keep your elbows straight and position your shoulders directly above your hands.

- Use your upper body weight (not just your arms) as you push straight down on (compress) the chest at least 2 inches (approximately 5 centimeters) but not greater than 2.4 inches (approximately 6 centimeters). Push hard at a rate of 100 to 120 compressions a minute.

- If you haven’t been trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, continue chest compressions until there are signs of movement or until emergency medical personnel take over. If you have been trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, go on to opening the airway and rescue breathing.

Airway: Open the airway

- If you’re trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and you’ve performed 30 chest compressions, open the person’s airway using the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver. Put your palm on the person’s forehead and gently tilt the head back. Then with the other hand, gently lift the chin forward to open the airway.

Breathing: Breathe for the person

Rescue breathing can be mouth-to-mouth breathing or mouth-to-nose breathing if the mouth is seriously injured or can’t be opened.

- With the airway open (using the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver), pinch the nostrils shut for mouth-to-mouth breathing and cover the person’s mouth with yours, making a seal.

- Prepare to give two rescue breaths. Give the first rescue breath — lasting one second — and watch to see if the chest rises. If it does rise, give the second breath. If the chest doesn’t rise, repeat the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver and then give the second breath. Thirty chest compressions followed by two rescue breaths is considered one cycle. Be careful not to provide too many breaths or to breathe with too much force.

- Resume chest compressions to restore circulation.

- As soon as an automated external defibrillator (AED) is available, apply it and follow the prompts. Administer one shock, then resume cardiopulmonary resuscitation — starting with chest compressions — for two more minutes before administering a second shock. If you’re not trained to use an AED, an emergency medical operator may be able to guide you in its use. If an AED isn’t available, go to step 5 below.

- Continue cardiopulmonary resuscitation until there are signs of movement or emergency medical personnel take over.

Hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation

To carry out a chest compression:

- Place the heel of your hand on the breastbone at the center of the person’s chest. Place your other hand on top of your first hand and interlock your fingers.

- Position yourself with your shoulders above your hands.

- Using your body weight (not just your arms), press straight down by 5-6cm (2-2.5 inches) on their chest.

- Keeping your hands on their chest, release the compression and allow the chest to return to its original position.

- Repeat these compressions at a rate of 100 to 120 times per minute until an ambulance arrives or you become exhausted.

When you call for an ambulance, telephone systems now exist that can give basic life-saving instructions, including advice about CPR. These are now common and are easily accessible with mobile phones.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation with rescue breaths

If you’ve been trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, including rescue breaths, and feel confident using your skills, you should give chest compressions with rescue breaths. If you’re not completely confident, attempt hands-only CPR instead (see above).

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for adults

- Place the heel of your hand on the center of the person’s chest, then place the other hand on top and press down by 5-6cm (2-2.5 inches) at a steady rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute.

- After every 30 chest compressions, give two rescue breaths.

- Tilt the casualty’s head gently and lift the chin up with two fingers. Pinch the person’s nose. Seal your mouth over their mouth and blow steadily and firmly into their mouth for about one second. Check that their chest rises. Give two rescue breaths.

- Continue with cycles of 30 chest compressions and two rescue breaths until they begin to recover or emergency help arrives.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for children over 1 year

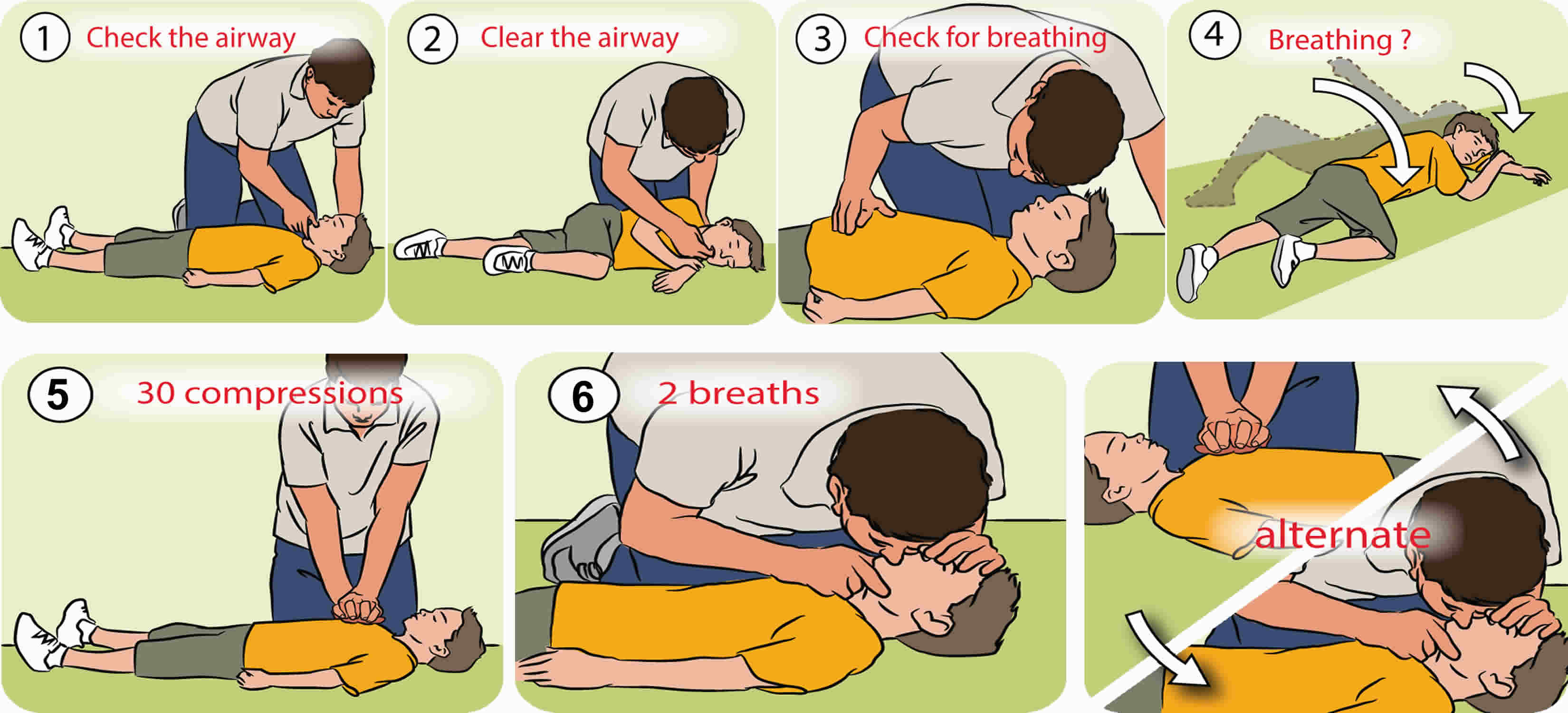

- Step 1: If a child is unconscious, the first step is to check his mouth for anything blocking the airway. This could include his tongue, food, vomit or blood.

- Step 2: If you find a blockage, roll him onto his side, keeping his top leg bent. This is the recovery position. Clear blockages with your fingers, then check for breathing.

- Step 3: If you find no blockages, check for breathing and look for chest movements. Listen for breathing sounds, or feel for breath on your cheek.

- Step 4: If the child is breathing, gently roll him onto his side and into the recovery position. Phone your local emergency services number and check regularly for breathing and response until the ambulance arrives. If the child is not breathing and responding, send for help. Phone local emergency services number and start CPR: 30 chest compressions, 2 breaths (if two people are conducting CPR, give two breaths after every 15 chest compressions).

- Step 5: Put the heels of your hands in the center of the child’s chest. Using the heel of your hand, give 30 compressions (if two people are conducting CPR, give two breaths after every 15 chest compressions). Each compression should depress the chest by about one third (at least 2 inches or approximately 5 centimeters, but not greater than 2.4 inches or approximately 6 centimeters).

- Step 6: After 30 compressions, take a deep breath, seal your mouth over the child’s mouth, pinch his nose and give two steady breaths. Make sure the child’s head is tilted back to open his airway.

- Step 7: Keep giving 30 compressions then 2 breaths until medical help arrives. If the child starts breathing and responding, turn him into the recovery position. Keep watching his breathing and be ready to start CPR again at any time.

Figure 2. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for for children over 1 year

Commotio cordis causes

Commotio cordis most commonly results from an impact to the left chest with a hard ball (e.g., a baseball) during sports activity. The sudden focal distortion of the myocardium results in ventricular fibrillation, causing sudden cardiac arrest in an otherwise structurally normal heart. It is distinct from a traumatic injury to the heart itself, like cardiac contusion or rupture, or penetrating chest injuries.

Disagreement exists around the exact mechanism for commotio cordis. However, experimental studies have shown that there are several factors involved. First, contact occurs directly over the heart in the anterior chest 6. The contact occurs during ventricular repolarization, specifically during the upstroke of the T-wave before its peak. If the impact occurs later than this, it is more likely to result in a transient complete heart block, left bundle branch block, or ST-segment elevation 7. While this period occupies only about 1% of the cardiac cycle, the relative proportion is increased with increasing heart rate, as may occur during exercise.

The impact energy must be sufficient to cause ventricular depolarization, which is estimated to be about 50 joules. This is easily achieved by a thrown baseball, for example, and the risk for commotio cordis appears to peak around 40 miles per hour. At higher speeds (with more energy), there is more likely to be resultant structural damage to the heart and/or chest wall, rather than isolated ventricular fibrillation 8. Smaller balls also carry a higher risk for commotio cordis, likely due to the impact being concentrated on a smaller surface area 9.

The mechanical force resulting from the precordial impact causes a stretch in myocardial cell membranes, which likely activates ion channels (mechanical-electrical coupling) 10. If the right number of these channels are in a vulnerable period of repolarization, the result of the depolarization may be ventricular fibrillation 11.

Commotio cordis prevention

Prevention remains an important consideration. Unfortunately, the use of chest wall protectors has failed to demonstrate a decrease in the incidence of commotio cordis 12. Thirty-seven percent of the reported cases have occurred with chest protectors in place 3. The American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology provide the following recommendations 13:

- “Measures should be taken to ensure successful resuscitation of commotio cordis victims, including training of coaches, staff, and others to ensure prompt recognition, notification of emergency medical services, and institution of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation.” (strong recommendation, based on moderate-quality evidence).

- “It is reasonable to use age appropriate safety baseballs to reduce the risk of injury and commotio cordis” (moderate recommendation, based on moderate-quality evidence).

- “Rules governing athletics and coaching techniques to reduce chest blows can be useful to decrease the probability of commotio cordis” (moderate recommendation, based on limited evidence).

Commotio cordis symptoms

Loss of consciousness is the most common sign of ventricular fibrillation. Ventricular fibrillation is the most frequent cause of sudden cardiac death. The condition’s rapid, erratic heartbeats cause the heart to abruptly stop pumping blood to the body. The longer the body is deprived of blood, the greater the risk of damage to your brain and other organs. Death can occur within minutes. Ventricular fibrillation must be treated immediately with defibrillation, which delivers an electrical shock to the heart and restores normal heart rhythm. The rate of long-term complications and death is directly related to the speed with which you receive defibrillation.

The following symptoms may occur within minutes to 1 hour before the collapse:

- Chest pain

- Dizziness

- Nausea

- Rapid or irregular heartbeat (palpitations)

- Shortness of breath

In most reported cases of commotio cordis, sudden death follows a seemingly inconsequential, nonpenetrating blow to the chest. Individuals who have witnessed the events universally believed that the chest trauma was of insufficient force to cause major injury and was out of proportion to the outcome. The person who is struck collapses immediately in most instances. In some instances, the individual has a transient period of consciousness, during which a brief purposeful activity, movement, or behavior (eg, picking up and throwing a ball, crying) is performed before final collapse.

A history consistent with commotio cordis involves a sudden impact with the anterior chest overlying the heart, followed by immediate cardiac arrest. This is most commonly a baseball; however, any impact may be present in the appropriate circumstances. Ventricular fibrillation may be observed if monitoring or an automated external defibrillator is available. Patients generally have no history of structural heart disease to explain the dysrhythmia, and the injury is not attributable to physical damage to the heart, cardiac contusion, or rupture. Penetrating injury is not the cause for arrest.

Physical exam findings may reveal a contusion overlying the heart, but this often takes time to develop, so should not be relied upon to confirm the diagnosis. A pulse is not present with ventricular fibrillation, and there is evidence of inadequate organ perfusion (i.e., unconsciousness).

Many times these deaths occur with no warning, indications to watch for include:

- Unexplained fainting (syncope). If this occurs during physical activity, it could be a sign that there’s a problem with your heart.

- Family history of sudden cardiac death. The other major warning sign is a family history of unexplained deaths before the age of 50. If this has occurred in your family, talk with your doctor about screening options.

Shortness of breath or chest pain could indicate that you’re at risk of sudden cardiac death. They could also indicate other health problems in young people, such as asthma.

Commotio cordis diagnosis

During resuscitation, rhythm strip analysis may help guide interventions. Point-of-care ultrasound may be useful to exclude concomitant injuries like pneumothorax or pericardial effusion/tamponade. Radiography has essentially no role in the management of commotio cordis, but may be important to identify concomitant serious injuries like a sternal fracture.

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology provide a strong recommendation based on moderate quality evidence that after resuscitation, patients with commotio cordis should undergo “a comprehensive evaluation for underlying cardiac pathology and susceptibility to arrhythmias” 13.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) may reveal evidence of myocardial injury, but it may be difficult to distinguish whether it occurred primarily, or secondary to the cardiac arrest. Troponin and echocardiogram may be useful to determine the presence of myocardial contusion. An echocardiogram may also help identify if there are other underlying structural abnormalities. Stress testing or cardiac catheterization may be considered to evaluate for coronary artery disease, as appropriate. Pharmacological testing for Brugada syndrome and long-QT syndrome should also be considered.

Commotio cordis treatment

Initial efforts should focus on resuscitation from cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. This includes closed chest compressions and early defibrillation. If the arrest is prolonged, it may be prudent to provide rescue ventilation and/or medications to improve coronary perfusion pressure (e.g., epinephrine). For an isolated blunt cardiac injury resulting in dysrhythmia, stabilization of the electrical activity may be the only necessary intervention. After resuscitation, appropriate post-cardiac arrest care should be implemented 14.

It may be appropriate to consider other forms of traumatic arrest, depending on the clinical scenario. These may include tension pneumothorax, cardiac or coronary laceration or tamponade, traumatic valvular injury, pulmonary laceration or great vessel injury, hemorrhagic shock, etc., or extrathoracic injuries, depending on the mechanism of injury.

Commotio cordis prognosis

There is evidence from a US Commotio Cordis Registry data that survival has improved concomitantly with increased awareness and access to medical care and public defibrillators. Data show that at least 59% of individuals have survived Commotio cordis in recent years and each year the survival rates are improving. The key reasons for the mortality are the failure of timely resuscitation and the presence of congenital heart disease. However, the standardization of resuscitation out of the hospital has seen a steady increase in survivors from all types of cardiac arrest including commotio cordis 15.

References- Maron BJ, Poliac LC, Kaplan JA, Mueller FO. Blunt impact to the chest leading to sudden death from cardiac arrest during sports activities. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995 Aug 10;333(6):337-42.

- Commotio cordis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/902504-overview

- Maron BJ, Haas TS, Ahluwalia A, Garberich RF, Estes NA, Link MS. Increasing survival rate from commotio cordis. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Feb;10(2):219-23.

- Maron BJ, Haas TS, Ahluwalia A, Garberich RF, Estes NA 3rd, Link MS. Increasing survival rate from commotio cordis. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Feb. 10(2):219-23.

- Tainter CR, Hughes PG. Commotio Cordis. [Updated 2019 Jun 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526014

- Link MS, Maron BJ, VanderBrink BA, Takeuchi M, Pandian NG, Wang PJ, Estes NA. Impact directly over the cardiac silhouette is necessary to produce ventricular fibrillation in an experimental model of commotio cordis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001 Feb;37(2):649-54.

- Link MS, Wang PJ, Pandian NG, Bharati S, Udelson JE, Lee MY, Vecchiotti MA, VanderBrink BA, Mirra G, Maron BJ, Estes NA. An experimental model of sudden death due to low-energy chest-wall impact (commotio cordis). N. Engl. J. Med. 1998 Jun 18;338(25):1805-11.

- Link MS, Maron BJ, Wang PJ, VanderBrink BA, Zhu W, Estes NA. Upper and lower limits of vulnerability to sudden arrhythmic death with chest-wall impact (commotio cordis). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003 Jan 01;41(1):99-104.

- Kalin J, Madias C, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Link MS. Reduced diameter spheres increases the risk of chest blow-induced ventricular fibrillation (commotio cordis). Heart Rhythm. 2011 Oct;8(10):1578-81.

- Bode F, Franz MR, Wilke I, Bonnemeier H, Schunkert H, Wiegand UK. Ventricular fibrillation induced by stretch pulse: implications for sudden death due to commotio cordis. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2006 Sep;17(9):1011-7.

- Maron BJ, Estes NA. Commotio cordis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010 Mar 11;362(10):917-27.

- Weinstock J, Maron BJ, Song C, Mane PP, Estes NA, Link MS. Failure of commercially available chest wall protectors to prevent sudden cardiac death induced by chest wall blows in an experimental model of commotio cordis. Pediatrics. 2006 Apr;117(4):e656-62.

- Link MS, Estes NA, Maron BJ., American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in Young, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and American College of Cardiology. Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Task Force 13: Commotio Cordis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2015 Dec 01;132(22):e339-42.

- Callaway CW, Donnino MW, Fink EL, Geocadin RG, Golan E, Kern KB, Leary M, Meurer WJ, Peberdy MA, Thompson TM, Zimmerman JL. Part 8: Post-Cardiac Arrest Care: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2015 Nov 03;132(18 Suppl 2):S465-82.

- De Gregorio C, Magaudda L. Blunt thoracic trauma and cardiac injury in the athlete: contemporary management. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2018 May;58(5):721-726.