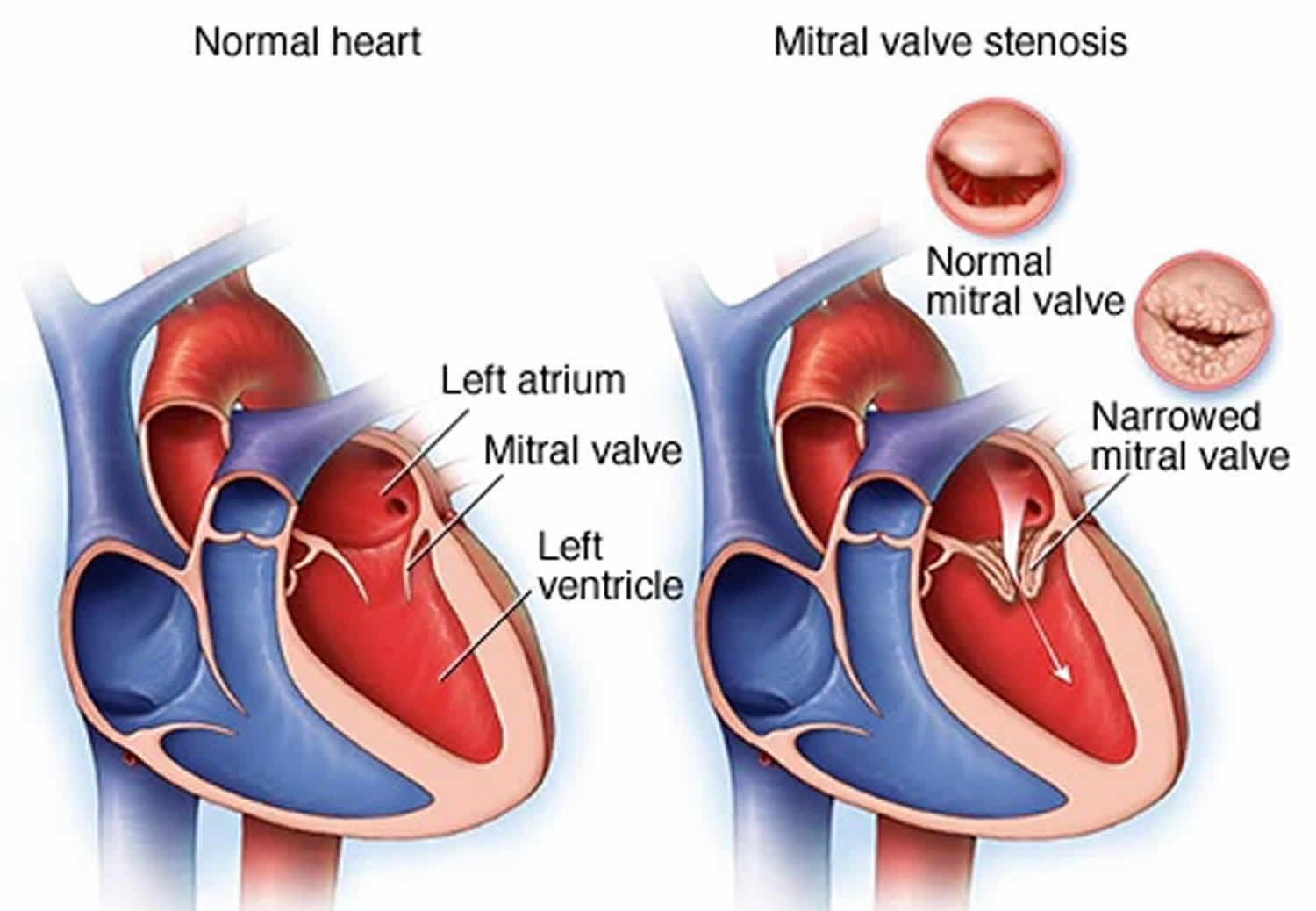

Mitral stenosis

Mitral stenosis also called mitral valve stenosis is a narrowing or blockage of the mitral valve where the mitral valve does not open as wide as it should, restricting the flow of blood through the heart. The narrowed mitral valve causes blood to backup in your heart’s upper-left chamber (the left atrium) instead of flowing into the lower-left chamber (the left ventricle). Most adults with mitral stenosis had rheumatic fever when they were younger. A rheumatic fever is a childhood illness that sometimes occurs after untreated strep throat or scarlet fever. Rheumatic fever is very rare in the US due to the use of effective antibiotics to prevent infections. Mitral valve stenosis may also be associated with aging and a buildup of calcium on the ring around the valve where the leaflet and heart muscle meet.

Mitral valve stenosis symptoms may appear or worsen anytime your heart rate increases, such as during exercise. An episode of rapid heartbeats may accompany these symptoms. Or they may be triggered by pregnancy or other body stress, such as an infection.

The mitral valve opens when blood flows from the left atrium to the left ventricle. Then the flaps close to prevent the blood that has just passed into the left ventricle from flowing backward. A defective mitral valve fails to either open or close fully. In mitral valve stenosis, pressure that builds up in the heart is then sent back to the lungs, resulting in fluid buildup (congestion) and shortness of breath.

Symptoms of mitral valve stenosis most often appear in between the ages of 15 and 40 in developed nations, but they can occur at any age even during childhood.

If mitral valve stenosis is not treated, it can lead to:

- atrial fibrillation – an irregular and fast heartbeat

- pulmonary hypertension – high blood pressure in the blood vessels that supply the lungs

- heart failure – where the heart cannot pump blood around the body properly.

You might not need treatment if you do not have any symptoms. Your doctor may just suggest having regular check-ups to monitor your condition.

If you have symptoms or the problem with your mitral valve stenosis is severe, your doctor may recommend:

- medicine to relieve your symptoms – such as medicines called diuretics to reduce breathlessness and medicines for atrial fibrillation

- mitral valve surgery – to replace the valve or stretch it with a small balloon (balloon valvuloplasty)

Call your doctor for an immediate appointment if you develop fatigue or shortness of breath during physical activity, heart palpitations, or chest pain.

If you have been diagnosed with mitral valve stenosis but haven’t had symptoms, talk to your doctor about follow-up evaluations.

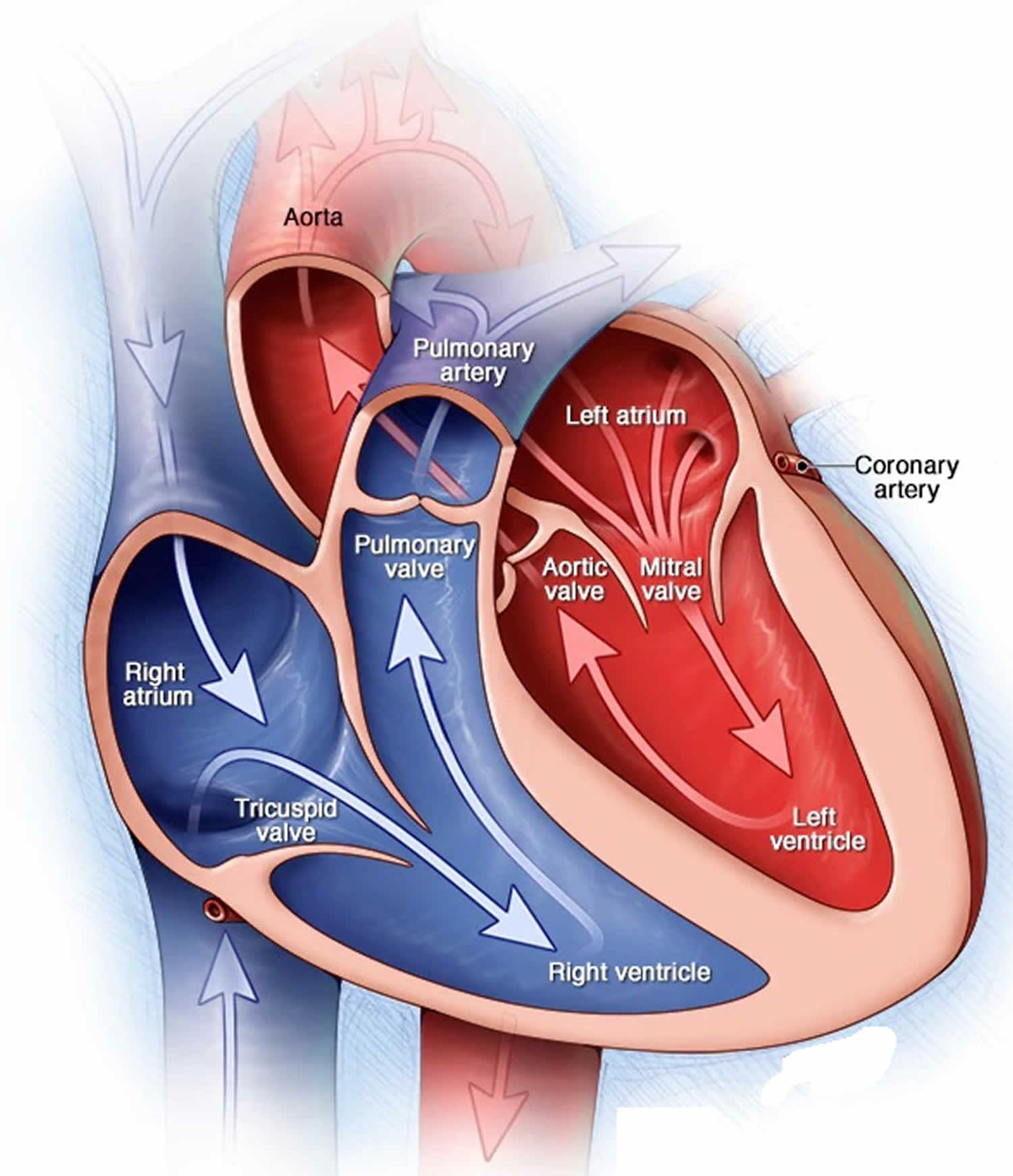

How your heart works

Your heart, the center of your circulatory system, consists of four chambers. The two upper chambers (atria) receive blood. The two lower chambers (ventricles) pump blood. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of your heart. The heart valves, which keep blood flowing in the right direction, are gates at the chamber openings.

Four heart valves open and close to let blood flow in only one direction through your heart. The mitral valve — which lies between the two chambers on the left side of your heart — comprises two flaps of tissue called leaflets.

The mitral valve is a tri-leaflet valve positioned between the left atrium and left ventricle. The normal mitral orifice area is 4 to 6 square centimeters 1. Under normal physiologic conditions, the mitral valve opens during left ventricular diastole to allow blood to flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle. The pressure in the left atrium and the left ventricle during diastole are equal. The left ventricle gets filled with blood during early ventricular diastole. There is only a small amount of blood that remains in the left atrium. With the contraction of the left atrium (the “atrial kick”) during late ventricular diastole, this small amount of blood fills the left ventricle 2.

Mitral valve areas less than 2 square centimeters causes an impediment to the blood flow from the left atrium into the left ventricle. This creates a pressure gradient across the mitral valve. As the gradient across the mitral valve increases, the left ventricle requires the atrial kick to fill with blood.

Mitral valve area less than 1 square centimeter causes an increase in left atrial pressure. The normal left ventricular diastolic pressure is 5 mmHg. A pressure gradient across the mitral valve of 20 mmHg due to severe mitral stenosis will cause a left atrial pressure of about 25 mmHg. This left atrial pressure is transmitted to the pulmonary vasculature resulting in pulmonary hypertension.

As left atrial pressure remains elevated, the left atrium will increase in size. As the left atrium increases in size, there is a greater chance of developing atrial fibrillation. If atrial fibrillation develops, the atrial kick is lost.

Thus, in severe mitral stenosis, the left ventricular filling is dependent on the atrial kick. With the loss of the atrial kick, there is a decrease in cardiac output and sudden development of congestive heart failure.

Mitral stenosis progresses slowly from initial signs of mitral stenosis to NYHA functional class II symptoms to atrial fibrillation to NYHA functional class III or IV symptoms 1.

Figure 1. Human heart anatomy

Mitral stenosis classification

Classification of severity of mitral valve stenosis

Mild

- Mean gradient (mmHg) less than 5

- Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mmHg) less than 30

- Valve area (cm²) less than 1.5

Moderate

- Mean gradient (mmHg) 5 to 10

- Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mmHg) 30 to 50

- Valve area (cm²) 1.0 to 1.5

Severe

- Mean gradient (mmHg) less than 10

- Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mmHg) greater than 50

- Valve area (cm²) less than 1.0

Mitral valve anatomy according to the Wilkins Score

Grade 1

- Mobility: Highly mobile valve with only leaflet tips restricted

- Thickening: Leaflet near normal in thickness (4 mm to 5 mm)

- Calcification: A single area of increased echo brightness

- Subvalvular Thickening: Minimal thickening just below the mitral leaflets

Grade 2

- Mobility: Leaflet mid to base portions have normal mobility

- Thickening: Mid leaflets normal, considerable thickening of margins (5-8 mm)

- Calcification: Scattered areas of brightness confirmed to leaflet margins

- Subvalvular Thickening: Thickening of chordal structures extending to one of the chordal length

Grade 3

- Mobility: Valve continues to move forward in diastole, mainly from the base

- Thickening: Thickening extending through the entire leaflet (5 mm to 8 mm)

- Calcification: Brightness extending into the mid portions of the leaflets

- Subvalvular Thickening: Thickening extended to distal third to the chords

Grade 4:

- Mobility: No or minimal forward movement of the leaflets in diastole

- Thickening: Considerable thickening of all leaflet tissue (more than 8 mm to 10 mm)

- Calcification: Extensive brightness throughout much of the leaflet tissue

- Subvalvular Thickening: Extensive thickening and shortening of all chordal structures extending down to the papillary muscles.

Mitral stenosis causes

Causes of mitral valve stenosis include:

- Rheumatic fever. A complication of strep throat, rheumatic fever can damage the mitral valve. Rheumatic fever is the most common cause of mitral valve stenosis. It can damage the mitral valve by causing the flaps to thicken or fuse. Signs and symptoms of mitral valve stenosis might not show up for years.

- Calcium deposits. As you age, calcium deposits can build up around the ring around the mitral valve (annulus), which can occasionally cause mitral valve stenosis.

- Other causes. In rare cases, babies are born with a narrowed mitral valve (congenital defect) that causes problems over time. Other rare causes include radiation to the chest and some autoimmune diseases, such as lupus.

Mitral stenosis is usually caused by rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease. This is where an infection causes the heart to become inflamed. Over time, it can cause the flaps of the mitral valve to become hard and thick. Other causes include hard deposits that form around the mitral valve with age or a problem with the heart from birth (congenital heart disease).

Risk factors for mitral stenosis

Mitral valve stenosis is less common today than it once was because the most common cause, rheumatic fever, is rare in the United States. However, rheumatic fever remains a problem in developing nations.

Risk factors for mitral valve stenosis include:

- History of rheumatic fever

- Untreated strep infections.

Mitral stenosis prevention

The best way to prevent mitral valve stenosis is to prevent its most common cause, rheumatic fever. You can do this by making sure you and your children see your doctor for sore throats. Untreated strep throat infections can develop into rheumatic fever. Fortunately, strep throat is usually easily treated with antibiotics.

Rheumatic fever prophylaxis with Benzathine penicillin is the primary prevention treatment in patients with streptococcal pharyngitis.

Mitral stenosis symptoms

Most people with mitral stenosis may feel fine with mitral valve stenosis or you may have minimal symptoms for decades. Mitral valve stenosis usually progresses slowly over time. When symptoms do happen, they may get worse with exercise or any activity that increases your heart rate. Mitral stenosis causes blood flow through the narrowed valve opening from the left atrium to the left ventricle to be reduced. As a result, the volume of blood bringing oxygen from the lungs is reduced, which can make you feel tired and short of breath. The volume and pressure from blood remaining in the left atrium increases which then causes the left atrium to enlarge and fluid to build up in the lungs. Mitral stenosis presents 20 to 40 years after an episode of rheumatic fever.

See your doctor if you develop:

- Trouble breathing at night or after exercise (breathlessness)

- Dizziness

- Coughing, which sometimes produces a pinkish, blood-tinged sputum

- Fatigue and tiredness

- Chest pain that gets worse with activity and goes away with rest

- Frequent respiratory infections such as bronchitis

- Heart palpitations (the feeling that the heart has skipped a beat)

- Swelling (edema) of the feet and ankles

- A hoarse or husky-sounding voice.

Symptoms may begin with an episode of atrial fibrillation. Pregnancy, a respiratory infection, endocarditis, or other cardiac conditions may also cause symptoms. Mitral stenosis may eventually lead to heart failure, stroke, or blood clots to various parts of the body.

Mitral valve stenosis may also produce signs that your doctor will find during your examination. These may include:

- Heart murmur

- Fluid buildup in the lungs

- Irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias)

On auscultation, the first heart sound is usually loud and maybe palpable due to increased force in the closing of the mitral valve.

The P2 (pulmonic) component of the second heart sound (S2) will be loud if severe pulmonary hypertension is due to mitral stenosis.

An opening snap is an additional sound that may be heard after the A2 component of the second heart sound (S2). This is the forceful opening of the mitral valve when the pressure in the left atrium is greater than the pressure in the left ventricle.

A mid-diastolic rumbling murmur with presystolic accentuation is heard after the opening snap. This murmur is a low pitch sound. It is best heard with the bell of the stethoscope at the apex. The murmur accentuates in the left lateral decubitus position and with isometric exercise.

Advanced mitral stenosis, presents with signs of right-sided heart failure (jugular venous distension, parasternal heave, hepatomegaly, ascites) and/or pulmonary hypertension.

Other signs include, atrial fibrillation, left parasternal heave (right ventricular hypertrophy due to pulmonary hypertension) and tapping the apical beat.

Mitral stenosis complications

Like other heart valve problems, mitral valve stenosis can strain your heart and decrease blood flow. Untreated, mitral valve stenosis can lead to complications such as:

- Pulmonary hypertension. This is a condition in which there’s increased pressure in the arteries that carry blood from your heart to your lungs (pulmonary arteries), causing your heart to work harder.

- Heart failure. A narrowed mitral valve interferes with blood flow. This can cause pressure to build in your lungs, leading to fluid accumulation. The fluid buildup strains the right side of the heart, leading to right heart failure. When blood and fluid back up into your lungs, it can cause a condition known as pulmonary edema. This can lead to shortness of breath and, sometimes, coughing up of blood-tinged sputum.

- Heart enlargement. The pressure buildup of mitral valve stenosis results in enlargement of your heart’s upper left chamber (atrium).

- Atrial fibrillation. The stretching and enlargement of your heart’s left atrium may lead to this heart rhythm irregularity in which the upper chambers of your heart beat chaotically and too quickly.

- Blood clots. Untreated atrial fibrillation can cause blood clots to form in the upper left chamber of your heart. Blood clots from your heart can break loose and travel to other parts of your body, causing serious problems, such as a stroke if a clot blocks a blood vessel in your brain.

Mitral stenosis diagnosis

Your doctor will ask about your medical history and give you a physical examination that includes listening to your heart through a stethoscope. Mitral valve stenosis causes an abnormal heart sound, called a heart murmur.

Your doctor also will listen to your lungs to check lung congestion — a buildup of fluid in your lungs — that can occur with mitral valve stenosis.

Your doctor will then decide which tests are needed to make a diagnosis. For testing, you may be referred to a cardiologist.

Diagnostic tests

Common tests to diagnose mitral valve stenosis include:

- Transthoracic echocardiogram. Sound waves directed at your heart from a wandlike device (transducer) held on your chest produce video images of your heart in motion. This test is used to confirm the diagnosis of mitral stenosis.

- Transesophageal echocardiogram. A small transducer attached to the end of a tube inserted down your esophagus allows a closer look at the mitral valve than a regular echocardiogram does.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG). Wires (electrodes) attached to pads on your skin measure electrical impulses from your heart, providing information about your heart rhythm. You might walk on a treadmill or pedal a stationary bike during an ECG to see how your heart responds to exertion.

- Chest X-ray. This enables your doctor to determine whether any chamber of the heart is enlarged and the condition of your lungs.

- Cardiac catheterization. This test isn’t often used to diagnose mitral stenosis, but it might be used when more information is needed to assess your condition. It involves threading a thin tube (catheter) through a blood vessel in your arm or groin to an artery in your heart and injecting dye through the catheter to make the artery visible on an X-ray. This provides a detailed picture of your heart.

Cardiac tests such as these help your doctor distinguish mitral valve stenosis from other heart conditions, including other mitral valve conditions. These tests also help reveal the cause of your mitral valve stenosis and whether the valve can be repaired.

Mitral stenosis treatment

If you have mild to moderate mitral valve stenosis with no symptoms, you might not need immediate treatment. Instead, your doctor will monitor your mitral valve to see if your condition worsens.

Home remedies

To improve your quality of life if you have mitral valve stenosis, your doctor may recommend that you:

- Limit salt. Salt in food and drinks may increase pressure on your heart. Don’t add salt to food, and avoid high-sodium foods. Read food labels and ask for low-salt dishes when eating out.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Keep your weight within a range recommended by your doctor.

- Cut back on caffeine. Caffeine can worsen irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias). Ask your doctor about drinking beverages with caffeine, such as coffee or soft drinks.

- Seek prompt medical attention. If you notice frequent palpitations or feel your heart racing, seek medical help. Fast heart rhythms that aren’t treated can lead to rapid deterioration in people with mitral valve stenosis.

- Cut back on alcohol. Heavy alcohol use can cause arrhythmias and make symptoms worse. Ask your doctor about the effects of alcohol on your heart.

- Exercise. How long and hard you’re able to exercise may depend on the severity of your condition and the intensity of exercise. But everyone should engage in at least low-level, regular exercise for cardiovascular fitness. Ask your doctor for guidance before starting to exercise, especially if you’re considering competitive sports.

- See your doctor regularly. Establish a regular appointment schedule with your cardiologist or primary care provider.

Women with mitral valve stenosis need to discuss family planning with their doctors before becoming pregnant. Pregnancy causes the heart to work harder. How a heart with mitral valve stenosis tolerates the extra work depends on the degree of stenosis and how well the heart pumps. Throughout your pregnancy and after delivery, your cardiologist and obstetrician should monitor you.

Medications

No medications can correct a mitral valve defect. However, certain drugs can reduce symptoms by easing your heart’s workload and regulating its rhythm.

Your doctor might prescribe one or more of the following medications:

- Diuretics to reduce fluid accumulation in your lungs or elsewhere.

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants) to help prevent blood clots. A daily aspirin may be included.

- Beta blockers or calcium channel blockers to slow your heart rate and allow your heart to fill more effectively.

- Anti-arrhythmics to treat atrial fibrillation or other rhythm disturbances associated with mitral valve stenosis.

- Antibiotics to prevent a recurrence of rheumatic fever if that’s what caused your mitral stenosis. Rheumatic fever prophylaxis with Benzathine penicillin is the primary prevention treatment in patients with streptococcal pharyngitis.

Endocarditis prophylaxis should only be given to high-risk patients before dental procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissue or perforation of the oral mucosa. High-risk patients are those patients with a prosthetic heart valve or prosthetic material used for valve repair, previous history of infective endocarditis, and cardiac valvuloplasty.

Procedures

You may need valve repair or replacement to treat mitral valve stenosis, which may include surgical and nonsurgical options.

Percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty

Balloon valvuloplasty also called percutaneous mitral commissurotomy or balloon valvotomy, is a procedure that can be used to widen the mitral valve if you have mitral stenosis. It’s usually done using local anaesthetic, where you remain awake but your skin is numbed. In this procedure a doctor inserts a soft, thin tube (catheter) tipped with a balloon in an artery in your arm or groin and guides it to the narrowed valve. Once in position, the balloon is inflated to widen the valve, improving blood flow. The balloon is then deflated, and the catheter with balloon is removed.

For some people, balloon valvuloplasty can relieve the signs and symptoms of mitral valve stenosis. However, you may need additional procedures to treat the narrowed valve over time.

Not everyone with mitral valve stenosis is a candidate for balloon valvuloplasty. This procedure is generally less effective than replacing the mitral valve, but recovery tends to be quicker and it may be a better option if your valve is not too narrow or you’re at an increased risk of surgery complications (for example, if you’re pregnant or frail). Talk to your doctor to decide whether it’s an option for you.

Mitral valve surgery

Surgical options include:

- Commissurotomy. If balloon valvuloplasty isn’t an option, a cardiac surgeon might perform open-heart surgery to remove calcium deposits and other scar tissue to clear the valve passageway. Open commissurotomy requires that you be put on a heart-lung bypass machine during the surgery. You may need the procedure repeated if your mitral valve stenosis redevelops.

- Mitral valve replacement. If the mitral valve can’t be repaired, surgeons may perform mitral valve replacement. Mitral valve replacement is usually only done if you have mitral stenosis or mitral prolapse or regurgitation and are unable to have a valve repair. In mitral valve replacement, your surgeon removes the damaged valve and replaces it with a mechanical valve or a valve made from cow, pig or human heart tissue (biological tissue valve). Biological tissue valves degenerate over time, and often eventually need to be replaced. The operation is carried out under general anesthetic, where you’re asleep. Your surgeon will usually replace the valve through a single cut along the middle of your chest. People with mechanical valves will need to take blood-thinning medications for life to prevent blood clots. Most people experience a significant improvement in their symptoms after surgery, but speak to your surgeon about the possible complications. The risk of serious problems is generally higher than with mitral valve repair. Your doctor will discuss with you the benefits and risks of each type of valve and discuss which valve may be appropriate for you.

Mitral stenosis prognosis

Prior to the era of open-heart surgery, the prognosis for most patients with mitral stenosis was poor. In the era of mitral valve replacement, the prognosis is excellent. Survival is significantly better for patients undergoing an open mitral valve replacement compared to a commissurotomy. Today, there is an 80% survival at ten years, but in patients who have developed pulmonary hypertension, the survival is less than 3 years. Other complications that may result in high morbidity include stroke and persistent atrial fibrillation 3.

References- Shah SN, Sharma S. Mitral Stenosis. [Updated 2019 Aug 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430742

- Imran TF, Awtry EH. Severe Mitral Stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018 Jul 19;379(3):e6.

- Pradhan RR, Jha A, Nepal G, Sharma M. Rheumatic Heart Disease with Multiple Systemic Emboli: A Rare Occurrence in a Single Subject. Cureus. 2018 Jul 11;10(7):e2964.