Cronkhite Canada syndrome

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome also called Canada-Cronkhite disease, is an extremely rare disease characterized by various intestinal polyps, loss of taste, hair loss, and nail growth problems 1. Worldwide, over 500 Cronkhite-Canada syndrome cases have been reported in the past 50 years, primarily in Japan but also in the United States and other countries 2. Based on the large Japanese series, the estimated incidence of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is about 1 case per million population 2. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is difficult to treat because of malabsorption that accompanies the polyps. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome occurs primarily in the older population (average age 59 with a range of 31 to 86 years) and predominantly occurs in males. The ratio seems to be approximately 3 males to 2 females 3. The reported cases of infantile Cronkhite-Canada syndrome are scant (< 10) 4. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is considered to be an acquired, not hereditary disease.

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome treatment is based on controlling symptoms and providing support. The primary goal of treatment is to correct fluid, electrolyte and protein loss by nutritional supplementation or a nutritionally balanced liquid diet. Corticosteroids (i.e., prednisone) may be given occasionally to help reduce intestinal inflammation. Bacterial overgrowth in the intestines, which can cause malabsorption, may be treated with antibiotics. In rare cases, symptoms have resolved for no apparent reason (spontaneous remission).

Surgical removal of polyps may help to relieve some of the symptoms of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. However, they may recur or be too numerous to remove individually. If necessary, severely affected portions of the colon may be removed. Case reports have suggested the use of immunosuppressive treatment, including aziathioprin and ciclosporin, if other treatments are not effective.

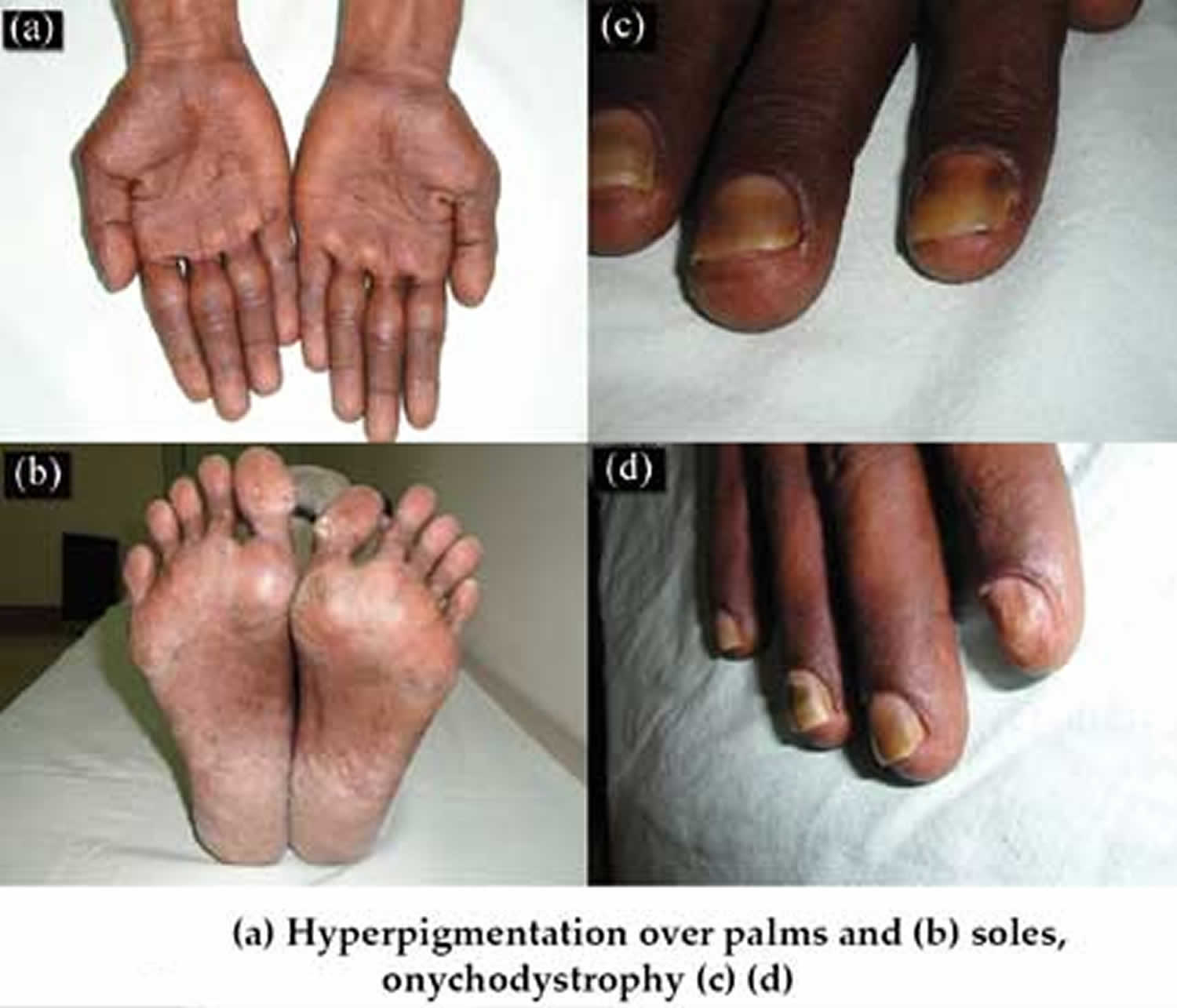

Figure 1. Cronkhite Canada disease

Cronkhite Canada syndrome causes

The exact cause of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is unknown. It seems to occur for no known reason (sporadically) and is not thought to be hereditary.

The possibilities of asymptomatic offspring or afflicted patients have not been excluded. Reports suggest immune dysregulation as the basis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome 5. Many patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome have positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) as well as a variety of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, polymyalgia rheumatica, or hypothyroidism 6. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome patients have also been found to have elevated serum IgG4 levels. Positive results for immune staining of IgG4 plasma cells in stomach and colonic polyps have been also reported from patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome 7. The autoimmune etiology is further supported by the excellent clinical response to systemic steroids and azathioprine 8.

Negoro et al 9 demonstrated that germlike mutations of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue), located at 10q23.3, which is responsible for another gastrointestinal polyposis syndrome (Cowden disease), is not detected in persons with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Boland et al 10 performed whole exome sequencing on germline DNA from blood samples and polyp tissue from a gastric and a colonic polyp. The polyps did not share common nonsilent somatic mutations, suggesting distinct origin without a common molecular pathway. On germline analysis, they identified a rare variant affecting PRKDC, protein kinase DNA-activated catalytic polypeptide (DNA-PKcs).

Senesse et al 11 described Cronkhite-Canada syndrome in association with arsenic poisoning.

The principal gastrointestinal symptoms, weight loss, and weakness probably are due to altered digestive, motive, absorptive, and secretory functions of the gut and bacterial overgrowth syndrome. Clostridium difficile is isolated quite frequently in the stool. The exact cause of diarrhea is not clear. The symptom is likely related to the presence of polyps; however, the impaired bowel motility may cease without alteration of the size and number of polyps. Gastric polyps have been found to be infected with Helicobacter pylori 12. Elevated gastric acid secretion also was found in one reported case.

Ectodermal changes (ie, hyperpigmentation, alopecia, nail dystrophy) are believed to be due to protein loss and malabsorption; however, cutaneous manifestations preceded onset of diarrhea in many patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Authors suggest that ectodermal changes are an inherent part of the syndrome, not secondary to malabsorption, because similar ectodermal lesions do not appear in other protein-losing gastroenteropathies 13. Moreover, based on the latest scalp biopsy histological findings, the hypothesis of an autoimmune causality for Cronkhite-Canada syndrome hair loss have been proposed 14. Regrowth of hair was noted after treatment, during spontaneous remission, and even during active disease. Hyperpigmentation also was noted to be reversible after and without any specific therapy.

Presence of edema correlates well to hypoalbuminemia.

Neurologic or psychotic symptoms occurred as a cause of hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypokalemia.

Mild-to-moderate anemia is secondary to malabsorption (ie, iron, vitamin B-12, folate deficiency), blood loss, or both. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome concomitant with myelodysplastic syndrome has been diagnosed 15.

Cataract progression likely is associated with hypoproteinemia and hypocalcemia. Low calcium levels in the aqueous humor were believed to promote changes in lens membrane permeability and subsequent membrane disruption. A flux of sodium ions was postulated to occur from the aqueous into the lens, resulting in overhydration and production of a cortical lens opacity.

The cause of macrocephaly, typically present in cases of the juvenile Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, is unknown. An increase of arachnoid cysts was demonstrated.

Cronkhite Canada syndrome pathophysiology

Gastrointestinal lesions in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome are hamartomatous polyps generally involving the entire gastrointestinal tract except for the esophagus 16. Histologically they reveal pseudopolypoid-inflammatory changes. One report describes an esophageal squamous cell papilloma 17.

Cutaneous symptoms are believed to be due to malabsorption; however, ectodermal changes did not appear to parallel the disease activity and improved despite gut dysfunction in some reported cases. Multiple brownish macules and patches also preceded the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms in one of the first reported cases of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

Infantile Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (similar to typical Cronkhite-Canada syndrome) includes juvenile gastrointestinal polyps, alopecia, nail changes, and macrocephaly. Infantile Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is believed to be a special variant of juvenile gastrointestinal polyposis. Its mode of inheritance is assumed to be autosomal recessive; however, parental consanguinity was not present in either described case. This raises the question of whether infantile Cronkhite-Canada syndrome may be a sporadic condition 4.

Cronkhite Canada syndrome symptoms

The symptoms of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome occur because of multiple polyps occurring in the stomach, small intestine, colon and, less frequently, the esophagus. These include chronic or recurring watery diarrhea, cramps, and abdominal discomfort. These people may also have abnormally low levels of protein in the blood (protein-losing enteropathy), causing a feeling of general ill health (cachexia), malnutrition, nausea and vomiting.

The earliest symptoms reported are changes in taste and loss of smell. Patients can even experience a profound loss of appetite, sometimes to the point of malnutrition, weight-loss and/or excess fluid accumulation in the arms and legs (peripheral edema). An imbalance of certain essential minerals (electrolytes) may occur because of chronic diarrhea. Some people with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome may also have large skin bruises (ecchymotic plaques) and/or impaired lung function. Other symptoms may include loss of hair (alopecia), large areas of dark spots on the skin (hyperpigmentation) and degenerative changes and, eventually, loss of the fingernails (onychodystrophy).

Patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome can also have coexisting autoimmune disorders, where the body develops antibodies against an organ, thereby attacking itself, e.g. hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematous, etc.

Cronkhite Canada syndrome diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for Cronkhite Canada Syndrome is based on symptoms and particular features; however, there is no specific diagnostic test for this syndrome. The mean age of onset is 60, ranging from 31 to 86 years old. There are usually large numbers of polyps in the digestive tract, most often sparing the esophagus. The polyps have hamartomatous features, meaning they contain mucus and are inflamed within an intact surface.

Besides the gastrointestinal tract, findings in the skin are also diagnostic for this disease. Patients experience alopecia (loss of hair), dark spots on the skin of the arms, legs and face (hyperpigmented macules) and have a loss of finger nails (onychodystrophy).

One test that can be positive with this syndrome is IgG4 plasma cells but a negative test does not rule out the syndrome. The most important aspects for a diagnosis of Cronkhite Canada Syndrome are the aforementioned physical presentations as there is no particular test to provide a definitive diagnosis of the syndrome.

Laboratory studies

Various laboratory studies may include the following:

- Electrolyte and micronutrient determination – Hypokalemia; hypocalcemia; depressed serum levels of zinc, iron, copper, and magnesium; and vitamin B-12

- Hematology – Depressed white blood cell count, hemoglobin, red blood cell count, and hematocrit

- Serum proteins – Hypoproteinemia with hypoalbuminemia; increased in alpha1 globulin level

- Raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Elevated serum levels of gastrin, histamine-fast achlorhydria, hypochlorhydria.

- Biochemical and hematologic tests – Total protein level; albumin level; glucose and lipids concentration; iron, magnesium, zinc, calcium, sodium, potassium, and copper concentrations; ESR; CRP

- Decreased cholinesterase activity

- Stool examination – Occult blood and Sudan III staining

- Helicobacter pylori infection test

Imaging studies

Endoscopic also wireless capsule endoscopy) procedures (ie, panendoscopy, gastroscopy, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy) reveal polyp lesions of the sessile or semipedunculated type throughout the stomach, duodenum, ileum, and colon, sparing the esophagus 18. Ikeda et al 19 found pedunculated polyps in patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. A few reports have described selective sparing of the stomach, small intestine, and/or the colorectum. Lesion size has varied from a few millimeters to 2 cm in diameter 20. Endoscopic findings in the stomach also include reddish and edematous granular lesions with mucoid exudate and giant folds.

Murata et al 21 applied a prototype of a magnifying single-balloon enteroscope to observe the entire small bowel intestine in a patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Further analysis should be done to investigate its usefulness as a diagnostic tool.

Abdominal CT scanning may reveal thickened gastric folds.

Regarding radiography, a barium enema and small intestine double-contrast radiology examination show polypoid lesions.

A CT endoscopy using a multidetector-row CT scan with 3-dimensional reconstruction has been shown to be useful for the detection of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps and for the monitoring of effects of therapy 22.

Magnified chromoendoscopy with crystal violet reveals sparsely distributed crypt openings with widening of the pericryptal space on the surface of the polyps and the intervening colonic mucosa 23.

Fluoroscopic examination of the stomach may show rough granular changes of the mucosa with edematous giant rugae and polypoid lesions.

Scintigraphy using technetium Tc 99m–labeled human albumin may result in leakage to the gastrointestinal tract.

Consider intraoperative or postoperative examination of p55 immunoreactivity accumulation in the tissue suspected of having a carcinomatous component.

Other tests

Other tests may include the following:

- Presence of antinuclear antibodies, usually with a nucleolar pattern

- Malignancy markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha-fetoprotein)

- D-xylose absorption test (impaired)

- Glucose tolerance test (may be impaired)

- Fecal fat excretion (increased)

- Gastrointestinal clearance of alpha-1 antitrypsin (usually elevated)

- Culture of nail scrapings for fungi (for differential diagnosis)

- HIV testing (possibly)

- Stool culture for C difficile, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, and Campylobacter species and for parasites

- 14C-xylose breath test – Bacterial overgrowth syndrome, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth 6

pathology

Hyperpigmentation is related to an increase in melanin within the basal layer with or without the melanocyte proliferation, pigment incontinence, hyperkeratosis, and nonspecific perivascular inflammation 24.

Ong et al 25 reported an increased number of telogen hair follicles, hair follicle miniaturization, presence of pigment casts and peribulbar lymphoid cell infiltrate. These findings point to alopecia areata incognito as the probable cause of hair loss in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (Cronkhite-Canada syndrome). This variant of alopecia areata is characterized by acute diffuse hair thinning.

Such results contrast those formerly reported by Watanabe-Okada et al 26 in two patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. They described a diffuse anagen-telogen conversion with increased telogen hair follicles in the absence of miniaturization or hair follicle inflammation, previously suggesting that acute telogen effluvium triggered by malnutrition was the preceding factor inducing hair loss in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Given the complex spectrum of the syndrome, further research on scalp biopsies is required.

A case report presented the histologic evaluation of a nail matrix biopsy showing hypergranulosis. Matrix hypergranulosis is a common finding in numerous inflammatory nail diseases, suggesting that nail changes found in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome could be an inflammatory reaction, rather than a consequence of malnutrition as previously believed 27.

Histologically, polyps in patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome are pseudopolypoid-inflammatory changes with cystic dilatation. Ikeda et al 19 found that some of the colon polyps presented a histologic pattern of a tubulovillous adenoma and others exhibited that of a juvenile-type polyp. The latter polyps were characterized by the presence of elongated and/or tortuous crypts with microcystic dilatation and inflamed edematous wide stroma. The areas of focal intestinal metaplasia were present. Even though cellular atypia was present, the adenomatous polyps showed histologic similarity to juvenile polyps with inflamed edematous stroma and occasional cystic glands. Extensive diffuse mucosal thickening has been reported instead of individual polyp growth. Often, this diffuse thickening, possibly an early active stage of disease, is seen in the upper gastrointestinal tract, leading to giant gastric and/or duodenal rugal folds 28. Although rare, flat or atrophic mucosa has also been described in patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome 20.

According to Burke and Sobin 29, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps are characterized by their broad sessile base, expanded edematous lamina propria, and cystic glands. The only reliable distinction between Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and colonic juvenile polyposis is the pedunculated growth of the latter with the exception of the gastric polyps. Gastric polyps in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome are sessile and composed of focally dilated irregular foveolar glands within a lamina propria expanded by edema and often an inflammatory infiltrate. Most polyps contain smooth muscle fibers in the lamina propria, and a minority has surface erosions. Gastric Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps are quite similar to juvenile or hyperplastic polyps. Prominent mast cells, eosinophils, and IgG4 plasma cell infiltration have all been reported as well 30.

The most constant features of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps are a sessile base, an expanded edematous lamina propria, and dilated glands. Other features, including inflammation, a small number of smooth muscle fibers, and a complex contour, are variable.

Cronkhite Canada syndrome treatment

Because of the unknown cause, treatment for Cronkhite-Canada syndrome remains predominantly symptomatic. Controlled therapeutic trials have not been possible because of the rarity of the disease. Remissions may occur spontaneously.

The primary goal of the treatment is to correct fluid, electrolyte, and protein loss, and to regulate stool frequency. These measures help improve the patient’s general condition. Most patients need symptomatic treatment for abdominal pain.

The most effective treatment is combination therapy composed of systemic corticosteroids together with an antiplasmin, an elemental diet, and hyperalimentation (nutritional supplements). Antibiotics are used to correct intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. The indication for corticosteroids is gastrointestinal inflammation; however, its origin is not clear. Yamakawa et al 15 reported two cases of steroid-resistant Cronkhite-Canada syndrome that were effectively treated with cyclosporine. Dramatic improvement of clinical symptoms and endoscopic findings were observed in both cases. Another case in which multiple treatments, including steroids, azathioprine, adalimumab, and cyclosporine, failed was treated with sirolimus, with apparent clinical and endoscopic remission of the disease 31. One case has been reported to be treated with rituximab 32.

Reports describe clinical response in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, with improvement of symptoms, weight gain, and polyp regression. These findings reinforce the theory of this syndrome’s inflammatory etiology 33. Immunosuppression in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome patients should be cautiously performed, owing to the potential accelerated malignancy risk.

Nutritional supplementation includes oral and/or intravenous fluids, electrolytes, vitamins, minerals, amino acids, albumins, and lipids.

Transfusions are sometimes required for severe anemia or acute blood loss.

In one reported case with elevated gastric acid secretion, the patient responded very well to ranitidine therapy 34. Other medications used are sulfasalazine and metronidazole.

After Helicobacter pylori eradication, gastric polypectomy can be of value 12.

Emergent re-admission of patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome may occur because of significant diarrhea, gastrointestinal bleeding, intussusception, prolapse of gastric polyp-bearing mucosa, and thromboembolic episodes due to dehydration.

Surgical care

At present, surgery is needed only for complications of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, such us prolapse, bowel obstruction, and malignancy. Other authors suggest that surgical intervention should also be reserved for patients who are not responsive to conservative methods.

Surgical intervention carries a significant risk in weakened patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Careful consideration must be given to the clinical course of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome before administration of systemic corticosteroids.

Long-term monitoring

Some Cronkhite-Canada syndrome patients remain asymptomatic after the hospital treatment and do not require further therapy. Prolonged corticosteroid therapy is necessary in other patients.

Controlling the macronutrient and micronutrient balance, periodically performing endoscopic examination of the gastrointestinal tract, and testing for occult blood presence in the stool are recommended.

It is essential to explain that patients must be reliable with follow-up care and regular examination of the gastrointestinal tract. Large polyps (>1 cm in diameter) require biopsy and pathologic examination.

Cronkhite Canada syndrome prognosis

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is considered a relentlessly progressive disease with a variable course and poor prognosis depending mainly on control of protein and electrolyte balance. The mortality rate exceeds 50% regardless of therapy. The longest-surviving patients were alive 15 and 17.5 years after successful surgical treatment.

As reported in cases of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, coexistent malignant changes in the polyps, gastrointestinal bleeding, and the possibility of intussusception or prolapse of gastric polyp–bearing mucosa increase the mortality 35.

The first two described patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome died of starvation 7 and 8 months after the onset of symptoms.

Cases of spontaneous remission after nutritional support have been reported.

The prognosis in children is believed to be generally less optimistic than in adults.

Causes of death are attributable to severe cachexia, anemia, congestive heart failure, embolism, shock, bronchopneumonia, and postoperative complications. One third of patients die from intractable nutritional deficiency.

Appropriate corticosteroid therapy alongside nutritional support can alter the natural history of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Lasting polyp regression is associated with a markedly improved prognosis and decreased risk of cancer 36.

References- Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/cronkhite-canada-syndrome

- Goto A. [Cronkhite-Canada syndrome; observation of 180 cases reported in Japan]. Nihon Rinsho. 1991 Dec. 49 (12):221-6.

- Ward EM, Wolfsen HC. Review article: the non-inherited gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002 Mar. 16 (3):333-42.

- de Silva DG, Fernando AD, Law FM, Premarathne M, Liyanarachchi DS. Infantile Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 1997 Mar-Apr. 64(2):261-6.

- Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK, Sanderson SO, Smyrk TC, Chari ST, et al. Clinicopathologic Features and Treatment Outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: Support for Autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Sep 1.

- Traussnigg S, Dolak W, Trauner M, Kazemi-Shirazi L. Difficult case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, Clostridium difficile infection and polymyalgia rheumatica. BMJ Case Rep. 2016 Jan 27. 2016

- Li Y, Luo HQ, Wu D, Xue XW, Luo YF, Xiao YM, et al. [Clinicopathologic features of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and the significance of IgG4-positive plasma cells infiltration]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2018 Oct 8. 47 (10):753-757.

- Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK, Sanderson SO, Smyrk TC, Chari ST, et al. Clinicopathologic Features and Treatment Outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: Support for Autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Sep 1

- Negoro K, Takahashi S, Kinouchi Y, et al. Analysis of the PTEN gene mutation in polyposis syndromes and sporadic gastrointestinal tumors in Japanese patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Oct. 43(10 Suppl):S29-33.

- Boland BS, Bagi P, Valasek MA, Chang JT, Bustamante R, Madlensky L, et al. Cronkhite Canada Syndrome: Significant Response to Infliximab and a Possible Clue to Pathogenesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 May. 111 (5):746-8.

- Senesse P, Justrabo E, Boschi F, et al. [Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and arsenic poisoning: fortuitous association or new etiological hypothesis?]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999 Mar. 23(3):399-402.

- Kim MS, Jung HK, Jung HS, et al. [A Case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome showing resolution with Helicobacter pylori eradication and omeprazole]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006 Jan. 47(1):59-64.

- Hanzawa M, Yoshikawa N, Tezuka T, et al. Surgical treatment of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with protein-losing enteropathy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998 Jul. 41(7):932-4.

- Stefanaki C, Stratigos A. Alopecia in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Aug. 177 (2):348-349.

- Yamakawa K, Yoshino T, Watanabe K, Kawano K, Kurita A, Matsuzaki N, et al. Effectiveness of cyclosporine as a treatment for steroid-resistant Cronkhite-Canada syndrome; two case reports. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016 Oct 6. 16 (1):123.

- Chen HM, Fang JY. Genetics of the hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: a molecular review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009 Aug. 24 (8):865-74.

- Sharma V, Mandavdhare HS, Prasad KK, Dutta U. Gastrointestinal: Esophageal squamous cell papilloma in a patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec. 33 (12):1937.

- Jha AK, Kumar A, Singh SK, Madhawi R. Panendoscopic characterization of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Med J Armed Forces India. 2018 Apr. 74 (2):196-200.

- Ikeda K, Sannohe Y, Murayama H. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome developing after hemi-colectomy. Endoscopy. 1981 Nov. 13(6):251-3.

- De Petris G, Chen L, Pasha SF, Ruff KC. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome diagnosis in the absence of gastrointestinal polyps: a case report. Int J Surg Pathol. 2013 Dec. 21 (6):627-31.

- Murata M, Bamba S, Takahashi K, Imaeda H, Nishida A, Inatomi O, et al. Application of novel magnified single balloon enteroscopy for a patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jun 14. 23 (22):4121-4126.

- Nagata K, Sato Y, Endo S, Kudo SE, Kushihashi T, Umesato K. CT endoscopy for the follow-up of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007 Sep. 22(9):1131-2.

- Okamoto K, Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Nishiyama H, Ito M, Kohno S. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: remission after treatment with anti-Helicobacter pylori regimen. Digestion. 2008. 78(2-3):82-7.

- Herzberg AJ, Kaplan DL. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Light and electron microscopy of the cutaneous pigmentary abnormalities. Int J Dermatol. 1990 Mar. 29 (2):121-5.

- Ong S, Rodriguez-Garcia C, Grabczynska S, Carton J, Osborn M, Walters J, et al. Alopecia areata incognita in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Aug. 177 (2):531-534.

- Watanabe-Okada E, Inazumi T, Matsukawa H, Ohyama M. Histopathological insights into hair loss in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: diffuse anagen-telogen conversion precedes clinical hair loss progression. Australas J Dermatol. 2014 May. 55 (2):145-8.

- Chuamanochan M, Tovanabutra N, Mahanupab P, Kongkarnka S, Chiewchanvit S. Nail Matrix Pathology in Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: The First Case Report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017 Nov. 39 (11):860-862.

- Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, Ruprecht RM, Rajacich GM, Schwabe AD. The Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1982 Sep. 61(5):293-309.

- Burke AP, Sobin LH. The pathology of Cronkhite-Canada polyps. A comparison to juvenile polyposis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989 Nov. 13(11):940-6.

- Anderson RD, Patel R, Hamilton JK, Boland CR. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting as eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2006 Jul. 19 (3):209-12.

- Langevin C, Chapdelaine H, Picard JM, Poitras P, Leduc R. Sirolimus in Refractory Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome and Focus on Standard Treatment. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2018 Jan-Dec. 6:2324709618765893

- Firth C, Harris LA, Smith ML, Thomas LF. A Case Report of Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome Complicated by Membranous Nephropathy. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2018 Sep-Dec. 8 (3):261-267.

- Taylor SA, Kelly J, Loomes DE. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: Sustained Clinical Response with Anti-TNF Therapy. Case Rep Med. 2018. 2018:9409732

- Allbritton J, Simmons-O’Brien E, Hutcheons D, Whitmore SE. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of two cases, biopsy findings in the associated alopecia, and a new treatment option. Cutis. 1998 Apr. 61(4):229-32.

- Oberhuber G, Stolte M. Gastric polyps: an update of their pathology and biological significance. Virchows Arch. 2000 Dec. 437(6):581-90.

- Watanabe C, Komoto S, Tomita K, Hokari R, Tanaka M, Hirata I, et al. Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2016 Apr. 51 (4):327-36.